1. Introduction

A sense of belonging at school refers to students’ perception of being accepted, valued, and included in their school community [

1]. This experience of connection is widely recognised as a cornerstone of adolescents’ academic performance, psychological adjustment, and social participation [

2,

3]. When students feel that they belong, they are more likely to demonstrate motivation, persistence, and prosocial behaviour [

4,

5]. Conversely, weak belonging is associated with disengagement, loneliness, emotional difficulties, and higher risk of school dropout [

6,

7]. Although the importance of belonging has been widely acknowledged, the mechanisms through which it develops are complex and embedded in multiple ecological layers—ranging from personal competences to relational climates and broader sociocultural contexts. Belonging is not a static emotional state but a dynamic developmental process shaped by everyday interactions between students, teachers, and peers. Understanding this process requires the integration of complementary theoretical perspectives that jointly explain how internal needs, interpersonal bonds, and contextual structures contribute to students’ sense of connection and inclusion.

In this regard, four frameworks provide key conceptual guidance for the present study. Self-Determination Theory [

8] highlights relatedness as a basic psychological need essential for intrinsic motivation and mental health. Attachment Theory [

9] underlines the role of secure and supportive relationships with adults and peers in promoting emotional safety and exploration. Social Identity Theory [

10] focuses on group belonging and the development of social identity within the school community. Finally, the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework [

11] positions competence, confidence, connection, and caring as developmental assets that sustain thriving and resilience. In Portugal, school belonging has gained increasing attention as an indicator of inclusive education and adolescent well-being. National studies reveal heightened vulnerability among students from ethnic minorities, low-income backgrounds, and those with special educational needs. Structural inequities—such as unequal learning opportunities, early tracking, and digital divides—continue to shape adolescents’ connection to school [

12,

13]. Moreover, the rise of online communication and hybrid learning has introduced new spaces of affiliation and exclusion, reshaping how students experience connection and recognition [

14]. Despite this growing relevance, large-scale data on Portuguese students’ sense of belonging remain scarce. Existing studies are often regional or qualitative, limiting generalisability. Addressing this gap, the present research analyses school belonging in a nationally representative sample of Portuguese students. It identifies psychosocial predictors—socio-emotional competences, well-being indicators, psychological distress, school engagement, and experiences of bullying—aiming to provide evidence-based recommendations for fostering inclusion and positive youth development in educational settings.

2. Conceptual Framework: School Belonging as a Developmental and Contextual Construct

Belonging at school can be conceptualised simultaneously as a psychological need, a developmental asset, and an educational outcome. Theoretically, it links motivational, emotional, and social dimensions of adolescent experience, bridging internal capacities with external opportunities for participation and recognition. This multidimensional view emphasises that belonging does not depend solely on individual characteristics, but results from continuous interactions between personal competences, supportive relationships, and contextual structures that enable inclusion. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory, the need for relatedness is considered fundamental to self-regulation and motivation [

8]. Students who feel connected to others internalise school goals and values more readily, translating social inclusion into academic engagement. From an Attachment Theory perspective, consistent and supportive relationships with teachers and peers function as secondary attachment systems that provide emotional security and enable exploration [

15]. Social Identity Theory adds a collective dimension: belonging contributes to identity formation by fostering a sense of shared membership and mutual respect within the school community [

10]. Finally, PYD theory emphasises that the development of competence, confidence, connection, and character builds adaptive strengths that reinforce both engagement and belonging [

11].

Integrating these frameworks allows for a comprehensive conceptual model in which socio-emotional competences and developmental assets operate as protective factors, whereas psychological distress and bullying act as risk factors undermining inclusion. In this model, school belonging emerges both as an outcome of healthy developmental processes and as a mechanism that sustains motivation, resilience, and well-being over time. The model also acknowledges that school belonging is embedded in contextual and structural conditions—such as equity, diversity, and digital transformation—that can either foster or hinder adolescents’ capacity to feel connected and valued within their school communities.

Building on these frameworks, the present study examines how socio-emotional competences, relationships, and psychological adjustment jointly predict Portuguese adolescents’ perceived school belonging. This integrative perspective provides a foundation for understanding both risk and protection mechanisms in educational settings and informs strategies to promote inclusion and well-being in schools.

2.1. Socio-Emotional Skills and Positive Youth Development (PYD)

The development of school belonging is closely tied to students’ socio-emotional competences—the skills that allow them to understand and manage emotions, establish healthy relationships, and make responsible decisions [

3]. These skills are not only protective against psychological distress but also central to forming meaningful connections within the school context.

Within the framework of Positive Youth Development (PYD), socio-emotional skills are seen as foundational assets that promote thriving and reduce risk behaviours. PYD proposes the “Five Cs”—Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring—as developmental outcomes that foster resilience and community engagement [

11]. Empirical studies confirm that students who report higher levels of connection and competence also report stronger feelings of belonging and higher school engagement [

16,

17].

Educational interventions that integrate social-emotional learning (SEL) into the curriculum have demonstrated positive effects on both academic performance and school connectedness. These interventions help students navigate interpersonal challenges, regulate stress, and build a sense of shared purpose in school [

18].

While PYD emphasises the developmental value of competence, confidence, and connection, the present research integrates these assets with other psychological and contextual predictors to capture a more comprehensive picture of school belonging.

2.2. The Role of School Engagement and Relational Support

School engagement is a multidimensional construct that includes students’ emotional attachment to school, behavioural participation in academic and extracurricular activities, and cognitive investment in learning [

19]. It serves as both a facilitator and an indicator of school belonging.

Research consistently shows that students who experience supportive school environments—characterised by fairness, emotional safety, and inclusivity—are more likely to report high school engagement and belonging [

20]. These settings foster motivation, identity integration, and a sense of orientation towards the future.

In this context, the quality of teacher-student relationships is critical. Teachers who express empathy, show availability, and provide meaningful feedback promote a relational climate that supports belonging and participation [

15]. Such relationships act as protective buffers, particularly for students experiencing social or academic difficulties.

Relational support from peers also plays a vital role. Peer acceptance and collaboration increase students’ opportunities to engage in school life meaningfully and reduce the risk of social isolation [

6]. Inversely, experiences of rejection or social conflict—especially bullying—can severely undermine students’ connection to school.

Accordingly, school engagement and the quality of relational support are treated here as contextual assets that may strengthen or undermine students’ sense of belonging.

2.3. Structural Barriers: Inequity, Exclusion, and Vulnerability

Despite the universal need for belonging, students do not experience school engagement and inclusion equally. Structural factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, disability, and linguistic background contribute to disparities in access to supportive school environments [

21].

Students from marginalised groups often face implicit biases, lower expectations, and fewer opportunities for meaningful participation. These dynamics lead to cumulative disadvantage and reduced academic self-concept, undermining both school engagement and the sense of belonging [

22].

Bullying, discrimination, and exclusionary practices further weaken the social fabric of the school, creating psychological harm and alienation. A meta-analysis by Gini et al. [

23] confirmed that victimisation is strongly associated with diminished school belonging, especially when institutional responses are perceived as inadequate.

Addressing these inequities requires systemic change—policies that prioritise equity, culturally responsive pedagogies, and the active dismantling of discriminatory norms within school cultures [

3,

24].

These structural inequities are especially relevant in the Portuguese context, where persistent educational inequalities and cultural diversity shape how belonging is experienced.

2.4. Belonging in a Digital and Hybrid Educational Landscape

The digital transformation of education—accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic—has introduced new dynamics in how students engage with school and each other. While digital platforms can extend learning opportunities and social connectivity, they also risk increasing disconnection, surveillance, and exposure to cyberbullying [

14,

25].

Digital belonging is emerging as a distinct but interrelated construct, encompassing students’ sense of inclusion, recognition, and participation in virtual learning environments. When digital tools are integrated with care and relational intention, they can foster community and co-learning. When used rigidly or without emotional scaffolding, they may exacerbate disengagement and isolation.

Schools face the challenge of fostering belonging in both physical and digital spaces—ensuring continuity of care, opportunities for voice and expression, and inclusive digital literacy. This requires training for teachers, platform design centred on collaboration, and digital well-being policies that align with educational inclusion goals.

This dimension is particularly salient in contemporary adolescence, and we therefore include digital-related risks (e.g., bullying) and protective factors when analysing predictors of belonging.

3. Aim of the Study

The main objective of this study is to analyse and characterise the levels of school belonging among Portuguese students, while identifying psychosocial predictors that may act as protective or risk factors. By integrating socio-emotional skills, psychological well-being, symptoms of distress, bullying, and school engagement, the study seeks to provide evidence-based guidelines for action in educational settings.

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Research Design and Procedures

This study used a cross-sectional design, based on data from the 2nd National Study of the Observatory of Psychological Health and Well-being [

26]. A stratified random sampling of school clusters across the NUTS III regions was carried out. Each selected school was contacted by email or telephone and invited to participate. Data collection took place between 23 January and 9 June 2024, coordinated by teachers and psychologists appointed by each school cluster.

Although schools were randomly selected, participation was voluntary. This procedure may have introduced sampling bias, as schools with greater availability or motivation could be overrepresented. All data were collected through self-report questionnaires, a method suitable for large-scale studies but subject to limitations such as common-method variance, which are acknowledged in the Discussion.

3.1.2. Ethical Considerations

The study complied with ethical standards for research involving minors, ensuring voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, and data protection. It was approved by the Portuguese Ministry of Education and by a Consultative Committee composed of representatives from the Portuguese Ministry of Education, the Directorate-General for Education and Science Statistics, the Directorate-General of Education, the Portuguese Psychologists Association, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, the National Program for the Promotion of School Success, and the Aventura Social Team/ISAMB, University of Lisbon (scientific coordination). Approval was granted on 10 February 2022.

Parental consent and student assent were obtained prior to data collection. Participation was voluntary, and no identifying information was collected.

3.1.3. Participants

The sample consisted of 3083 students from the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education and from secondary education (grades 5th to 12th). Of these, 49.5% identified as male and 50.5% as female, with a mean age of 13.64 years (SD = 2.53; range 9–20 years) (see

Table 1).

3.1.4. Measures

Validated instruments were used to assess socio-emotional skills, psychological well-being, psychological symptoms, positive youth development, school environment, bullying, and school belonging. For each measure, reliability coefficients were calculated in this study:

Socio-Emotional Skills Scale (SSES)—Assessed 12 competences (e.g., optimism, emotional control, resilience, confidence, sociability). Items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = always). Reliability in this study ranged from α = 0.72 to 0.88. Example: “I find it easy to make new friends” (sociability).

WHO-5 Well-Being Index (HBSC version)—5 items assessing positive well-being [

27] Items rated from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all of the time). Reliability: α = 0.84. Example: “Over the last two weeks, I have felt cheerful and in good spirits.”

HBSC Symptoms Checklist—Index of psychological distress based on the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey [

28]. Includes symptoms such as headaches, stomach aches, feeling low, irritability. Rated 0 (rarely) to 4 (almost every day). Reliability: α = 0.81.

DASS-21 (Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale)—Portuguese validated version [

29] p. 21 items, rated 0–3, assessing depression, anxiety, and stress. Reliability in this study: Depression α = 0.89; Anxiety α = 0.84; Stress α = 0.86.

Positive Youth Development Scale (PYD)—Adapted from Lerner et al. [

11]. Assesses competence, confidence, connection, and contribution. Rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Reliability: α = 0.78–0.87.

School Environment Scale—Evaluates fairness, inclusivity, and relational support within school. Rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Reliability: α = 0.82.

School Belonging (SSES subdimension)—Dependent variable. Example item: “I feel I belong at this school.” Reliability: α = 0.85.

Bullying Experiences—Items adapted from the HBSC survey, assessing frequency of being bullied in the past two months. Reliability: α = 0.79.

3.2. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted with SPSS (v.29) Descriptive statistics characterised the sample. Differences by gender and grade were examined through ANOVAs with post hoc Scheffé tests. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to identify predictors of school belonging.

Prior to regression, assumptions of normality were checked using skewness, kurtosis, and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, confirming the adequacy of parametric analyses. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) were calculated for all predictors, ranging between 1.21 and 2.34, indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Effect sizes were reported where relevant (η2 for ANOVA; β coefficients for regression).

3.3. Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the variables used in the study, including the number of participants (N), means, standard deviations (SD), and maximum and minimum values. The variables include social-emotional skills (SSES), indicators of psychological well-being (HBSC_WHO-5), symptoms of psychological distress (HBSC), levels of stress, symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression (DASS), indicators of positive development (PYD) and perception of the school environment. On average, students reported a level of sense of school belonging corresponding to 2.47 (SD = 0.53) out of a maximum of 4 and a minimum of 1.

There were statistically significant differences between genders in relation to involvement in school fights (χ2 (1) = 132.232; p < 0.001), with boys (25.2%) more frequently reporting involvement in school fights compared to girls (9.2%).

As shown in

Table 3, in the study of the differences between genders in relation to the level of feeling of belonging to school, statistically significant differences were found (F = 8.790;

p = 0.003), with male students tending to present a higher level of feeling of belonging to school (M = 2.5; SD = 0.53) compared to female students (M= 2.44; SD = 0.53). Although statistically significant, the effect size was small (η

2 < 0.02), indicating that gender differences accounted for only a limited proportion of the variance in school belonging.

Regarding the study of differences in the level of sense of school belonging amongst students according to school grades, illustrated in

Table 4, statistically significant differences were observed (F = 11.170;

p < 0.001). In the analysis of multiple comparisons, using the post hoc test by the Scheffé method, there were significant differences in the feeling of school belonging among 5th grade students (2.64; SD = 0.56) and 8th grade students (2.41; SD = 0.53), 9th grade (2.39; SD = 0.50), 10th grade (2.45; SD = 0.52), 11th grade (2.41; SD = 0.51) and 12th grade (2.38; SD = 0.55). Significant differences were also identified between 6th grade students (2.55; SD = 0.51) and 8th, 9th, 11th and 12th grade students. Additionally, there were statistically significant differences between 10th and 12th grade students. These results suggest that younger students tend to have higher levels of sense of belonging to school compared to older students. The effect sizes for grade-level differences were also small (η

2 < 0.02), highlighting that, despite their consistency, these differences explain only a modest proportion of the variance.

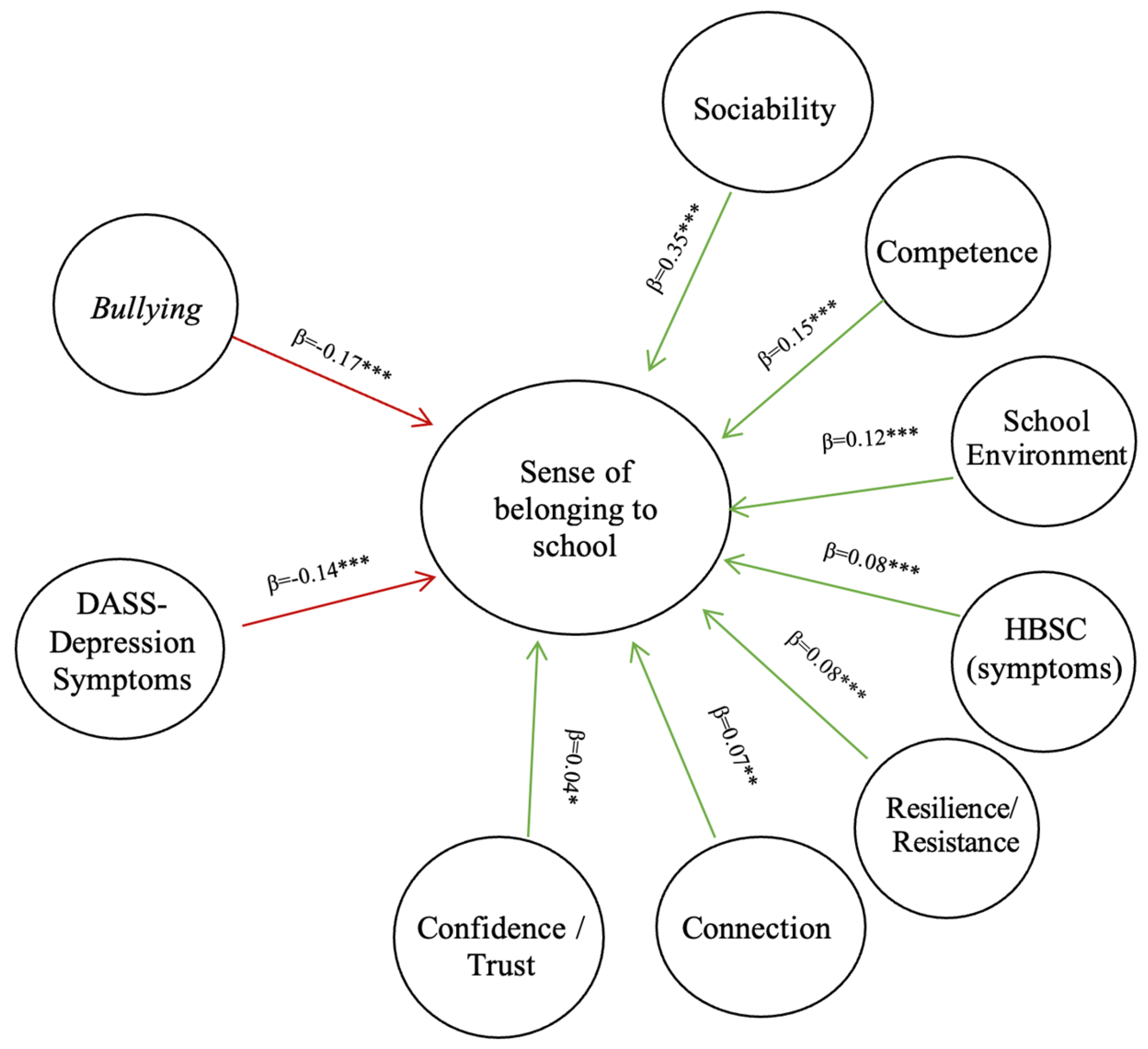

A linear regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of the feeling of school belonging (

Table 5 and

Figure 1). The adjusted model was statistically significant, explaining 58% of the total variance in the feeling of school belonging (R

2 = 0.58; F (26.2208) = 117.492;

p < 0.001). While the model explained a substantial proportion of the variance, several predictors demonstrated relatively small effect sizes (β < 0.10). Their contribution, although statistically significant given the large sample size, should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Among the variables evaluated, sociability stands out, presenting a significant positive association with the feeling of belonging to school (β = 0.35; t = 16.64; p < 0.001), indicating that students with greater sociability tend to report a greater sense of belonging to the school environment. Resilience/resistance (β = 0.08; t = 3.48; p < 0.001) and confidence (β = 0.04; t = 2.07; p = 0.04) also demonstrate positive and significant associations.

Within the scope of psychological symptoms, higher levels of symptoms (HBSC) are significantly positively related to the feeling of belonging at school (β = 0.08; t = 3.76; p < 0.001). However, in contrast, symptoms of depression demonstrate a negative association with the feeling of belonging (β = −0.14; t = −5.37; p < 0.001), highlighting the impact of emotional difficulties on school integration. his apparent contradiction—where general psychological symptoms showed a small positive association, but depressive symptoms were negatively related—requires careful interpretation and is further addressed in the discussion section.

The dimensions of Positive Youth Development (PYD) are also relevant to the model, especially competence (β = 0.15; t = 6.52; p < 0.001) and connectedness (β = 0.07; t = 3.07; p = 0.002), which are positively associated with the sense of belonging. The school environment emerges as a significant predictor (β = 0.12; t = 6.71; p < 0.001), reinforcing the role of the school context in strengthening integration.

Finally, there is a significant negative association between bullying and sense of belonging (β = −0.17; t = −11.04; p < 0.001), showing that experiences of exclusion or hostility at school harm the sense of belonging. The other predictors included in the model do not present statistically significant associations (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study offers an in-depth analysis of perceived school belonging amongst Portuguese students, highlighting how socio-emotional skills, psychological well-being, and school engagement interact to shape adolescents’ connection to their educational environment. The results confirm that school belonging is a multidimensional phenomenon, influenced by both individual competences and systemic relational dynamics. As the study is cross-sectional, these findings should not be interpreted in causal terms but rather as associations that highlight patterns relevant for educational practice.

As in the previous literature [

30,

31], the findings demonstrate developmental differences in perceived belonging. Younger students (particularly those in 5th and 6th grades) reported significantly higher levels of school belonging when compared to older students in secondary education. This pattern suggests that the school transition and increasing academic and social pressure experienced during adolescence may reduce students’ sense of inclusion and connection.

Gender differences also emerged: boys reported higher levels of belonging than girls, consistent with both national [

21] and international findings [

6]. These differences may reflect gendered experiences of schooling, social support, and emotional expression, and warrant further exploration in gender-sensitive research and intervention designs. However, the effect sizes for both age and gender were small, indicating that although systematic, these differences explained only a modest proportion of the variance. It is possible that broader cultural and structural gender norms, rather than biological or developmental differences, contribute to why girls report lower belonging, an issue that deserves further investigation in the Portuguese context.

The strongest positive predictor of school belonging was sociability, followed by resilience and confidence—all key dimensions of socio-emotional competence. These results are consistent with international evidence that suggests that emotional regulation, interpersonal skills, and self-efficacy foster social integration and mitigate emotional vulnerability [

3,

18]. Although the regression model explained a substantial proportion of variance (58%), several predictors presented small effect sizes (β < 0.10). Their inclusion is nevertheless theoretically relevant, as even weak associations may reflect important developmental processes when considered alongside stronger predictors.

These findings reinforce the importance of integrating Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programmes in schools, as students with stronger socio-emotional skills are more likely to navigate relational challenges and engage meaningfully in academic life [

17]. Notably, confidence, while a weaker predictor, highlights the internal dimension of belonging—feeling competent and valued within the school setting.

The positive association between school engagement and belonging supports the conceptual model that views emotional, behavioural, and cognitive participation in school life as both outcomes and facilitators of social inclusion [

19,

32]. Engaged students are more likely to build positive peer relationships, feel respected by teachers, and perceive school as meaningful—conditions that nurture belonging.

Within the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework, competence and connection emerged as significant contributors to school belonging. These dimensions reflect adolescents’ perception of their abilities and their relationships with others, aligning with the “Five Cs” model [

11,

16]. Their predictive power underscores the developmental relevance of designing school environments that cultivate students’ strengths, instead of just focusing on deficits.

While general psychological symptoms (HBSC) had a small positive association with school belonging, depressive symptoms (DASS) showed a strong negative relationship. This apparent contradiction may reflect measurement differences: the HBSC symptoms checklist captures broad and non-specific complaints, some of which may be transient and linked to everyday school stress, while the DASS assesses more severe depressive symptomatology. It is possible that students experiencing minor psychosomatic or emotional complaints remain engaged with school and therefore maintain a sense of belonging, whereas those with clinically relevant depressive symptoms feel disconnected and excluded. This finding aligns with research showing that students with higher depressive symptoms are more likely to feel disconnected, invisible, or unworthy in school contexts [

7]. Such students may experience cognitive distortions, social withdrawal, or reduced academic motivation which constitute barriers to relational and institutional belonging.

The most significant negative predictor in the model was bullying, confirming robust evidence that experiences of victimisation erode the foundations of school belonging [

23,

33]. Bullying introduces fear, mistrust, and exclusion, directly counteracting the conditions necessary for feeling safe, accepted, and valued.

This reinforces the importance of whole-school approaches to bullying prevention, where fostering empathy, promoting restorative practices, and ensuring relational justice are integral to building inclusive school cultures [

24,

34]. Cross-cultural studies similarly indicate that whole-school anti-bullying frameworks, when consistently implemented, are among the most effective ways to strengthen belonging and reduce risk behaviours [

35]. This underscores the need for integrated and preventive approaches in Portuguese schools.

Several methodological considerations should be acknowledged. The study is based on self-report questionnaires, which may introduce common-method variance. The sampling process, while stratified, depended on voluntary participation of schools, which could generate selection bias. Finally, as a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be inferred, and longitudinal research would be necessary to clarify developmental trajectories of belonging.

Future studies should also examine digital belonging more explicitly, as online peer relations and hybrid learning environments increasingly shape how adolescents experience school connectedness.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study provides robust evidence that school belonging among Portuguese adolescents is shaped by a constellation of individual competences, socio-emotional skills, and contextual experiences. Using a large and representative sample, the findings highlight both protective and risk factors that schools can address to promote inclusion and positive development.

Key protective factors identified include socio-emotional competences such as sociability, resilience, and confidence, as well as positive perceptions of the school environment and engagement in learning. These results reinforce the need to prioritise Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) within Portuguese curricula and to foster teacher–student and peer relationships that build trust and participation. While SEL is a well-established international recommendation, its effectiveness in this context is supported by national data showing the predictive role of socio-emotional skills for belonging.

Conversely, bullying and depressive symptoms emerged as the strongest risk factors, underscoring the urgency of prevention and early intervention. These findings suggest that anti-bullying programmes in Portugal should go beyond punitive measures and instead adopt whole-school approaches that integrate restorative practices, empathy development, and relational justice. Similarly, school-based mental health support should be reinforced, ensuring that students experiencing depressive symptoms are identified early and provided with pathways to care.

The results also draw attention to developmental transitions: younger students reported higher levels of belonging compared to those in secondary education, while girls reported lower belonging than boys. Although the effect sizes were modest, these patterns point to critical periods where targeted interventions may be particularly relevant—such as during the transition from basic to secondary education—and to the importance of gender-sensitive approaches that address structural inequalities shaping girls’ experiences in school.

These conclusions should be interpreted with caution, given the study’s reliance on self-report data, voluntary participation of schools, and cross-sectional design. Nonetheless, the findings offer valuable, evidence-based guidelines for action. Strengthening socio-emotional skills, fostering inclusive school climates, addressing bullying through systemic strategies, and supporting students’ mental health are priorities that can be operationalised through policies such as the National Program for the Promotion of School Success.

Finally, as schools increasingly operate in hybrid and digital environments, it is essential to consider how belonging is fostered both face-to-face and online. The present findings encourage further exploration of digital belonging as a key dimension of adolescents’ school experience in contemporary Portugal.