“It Was an Opportunity to Create Our Story in a Way in Which We Viewed It”: Arts-Based Truth-Telling by Black American Young Adult Alumni of the Child Welfare System

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

1.2. Achievement of Developmental Milestones Associated with the Transition to Adulthood for Black Youth Involved in the Child Welfare System

1.3. Disproportionalities and Disparities Impacting Black Youth in Child Welfare Nationally and in Kentucky

1.4. Truth Telling to Address Systemic Harms and Injustices

2. Materials and Methods

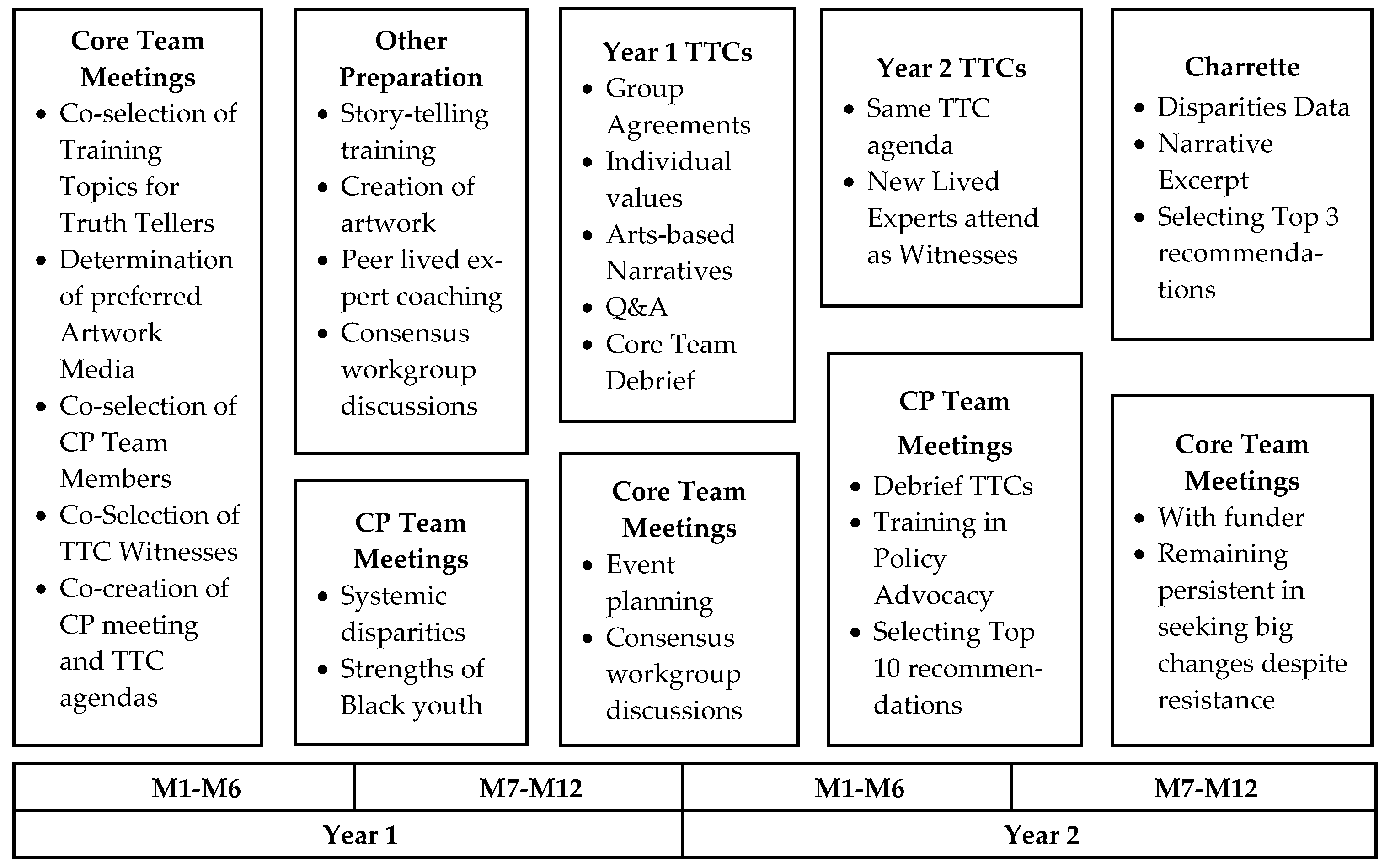

2.1. Project Description

2.2. Study Procedures

2.3. Collaborative Autoethnography

2.3.1. Data Collection

2.3.2. Data Analysis

2.4. Consensus Workgroup Process Using an Adapted Nominal Group Technique (NGT)

2.4.1. Distilling and Translating Information from TTC Narratives into Initial Pool of Recommendations: Adapted NGT Steps 1–2

2.4.2. Child Welfare System Recommendation Priorities Selection Process: Adapted NGT Steps 3–4

3. Results

3.1. Truth-Teller Descriptions of Artwork

3.2. Collaborative Autoethnography Findings

3.2.1. Strengths

3.2.2. Challenges

I did not like the fact that the adult participant who structured the entire event [the Charrette] and put in the most work over the two years of this grant did not receive an invite and was barred from coming to the event. I deserved to be there, and without mincing words, it was beyond disgusting that people barred (and allowed others to barr me) from attending an event that was a result of two years of my work/life story. As a black youth, it raises a lot of concerns that this grant work is “working” to eradicate, which takes away from the credibility of this work and creates a hypocritical lens to the work over the last two years.

At the end of the circle process…she [a child welfare system administrator]…said absolutely what the truth tellers would want to hear—that their testimonies were compelling and it made her think about what influence she had to make change. But then in private, she made what I would consider a flippant and almost callous comment, when she said, “I’ve heard this all before; there’s nothing new”. With that comment, I knew that even with a highly curated group of participants who the team thought would not only be receptive but perhaps influential, that truth telling processes are wrought with complexities that I hadn’t fully thought through. She—like so many others in the child welfare industry—have built their entire professional and in some cases personal identity and image around protecting children. So, processes and conversations that confront some of the hard truths of the industry are too painful to really digest or ingest—it becomes too personal. The industry is a self-protecting organism…She was walking away as a highly compensated executive whose company benefits when children are in “care”.

3.3. Consensus Workgroup: Adapted Nominal Group Technique

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TTCs | Truth Telling Circles |

Appendix A

Louisville TTC Project Recommended Changes for KY Child Welfare System-Related Procedures/Policies

- DCBS: Train all caseworkers and supervisors in Trauma-Informed Care Principles: Safety, Trustworthiness & Transparency, Peer Support, Collaboration, Empowerment, Humility & Responsiveness; And How to Use them when Interacting with Children and Adolescents in care

- DCBS: Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document that they explained the reasons for a placement change, preferably before or immediately after a move to the child with feedback and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR ramifications, if not completed consistently

- DCBS: Require caseworkers to give as much notice to the child as possible of an impending move; If an appropriate reason exists for why this cannot be done, require documentation of that reason; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document notice and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR ramifications, if not completed consistently

- DCBS: Require module on proper nutrition for children and adolescents as part of foster parent training

- DCBS: Include assessment of nutrition as part of monthly case worker meetings in foster home; include reporting from youth, and potentially log

- DCBS: Require module in cultural sensitivity, cultural competence, and racial trauma as part of foster parent training (e.g., values, different grooming and personal care products, etc.)

- DCBS: Require module on treating biological and foster children equally as part of foster parent training

- DCBS: Create Continuing Education/In-Service Training opportunities for foster parents (e.g., related to responding in a sensitive and effective way to children experiencing trauma symptoms, special sessions for those new to parenting, etc.)

- DCBS: Create short-term emergency foster care placements to allow enough time for caseworkers to contact all potential biological family members who may agree to care for the child; Encourage Family Finding through Campbell

- DCBS: Prioritize keeping siblings together; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document that they try to keep siblings together, and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR ramifications, if not completed consistently

- DCBS: Require training regarding coaching and supporting children to learn emotion regulation skills as part of foster parent training

- DCBS: Ask about efforts foster parents engage in to support foster children emotionally during monthly case worker visits

- DCBS: Offer emotional and social support services to foster parents, including mental health treatment, support groups, social activities, etc.

- DCBS: Require that case workers solicit and document child preferences for permanency planning; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document that they include children in permanency planning, and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR ramifications, if not completed consistently

- DCBS: Remove Adoption as the priority permanency plan; Replace with Reunification with Biological Family or Independence (adoption still an option, just not Priority)

- DCBS: Ask and document youth preferences regarding characteristics of foster family including race/ethnicity, region, number of other children, religion, etc.; Include preferences in decision-making process and document; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document youth preferences and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR ramifications, if not completed consistently

- DCBS: Supervisors and/or Electronic monitoring/auditing of following the Every Student Succeeds Act. If consistent with child preferences, prioritize allowing child to stay at same school and attend same faith community once placed in state’s care

- DCBS: Extend the period of support to adoptive families to 1–2 years post-adoption

- DCBS: Provide case management and support for biological parents to help them meet the goals in their care plan (in addition to the traditional substance use and mental health treatment, offer job training, job placement, connection to mutual aid collaboratives, biological parent advocacy organizations in the community, etc.)

- DCBS: Automate case worker documentation system to make quality control and auditing more efficient

- DCBS: Apply for additional funding such as federally funded programs and private foundations to expand training for case workers, social service providers, and youth development workers

- DCBS: Incorporate organizational culture and climate practices shown to reduce turnover among child welfare workers including (A) Organizational support (e.g., recognition of accomplishments; encourage workers self-care), (B) Supervisor support, (C) Fairness in pay, benefits, and promotions, (D) Inclusion in decision-making, and (E) Manageable workloads

- DCBS: Select foster parents based on motivation—perhaps structured interview and/or survey?

- DCBS: Allow all youth to extend care until 21, including those who are adopted or return home

- DCBS: Caseworkers to monitor that parents follow the normalcy laws during the monthly meetings; Allow youth to identify up to 2 or 3? extended family members who they are supported in staying in touch with (e.g., foster parents informed those family members are on an approved list, case workers check in to see if the child has been able to be in touch with them, etc.)

- DCBS: In addition, a separate number/ext that can be widely spread and goes directly to this branch. Even better if there is a line/number dedicated only to foster youth calls.

- DCBS: Be careful not to label children in files; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers are not using problematic labels in files and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR ramifications, if not completed consistently

- Ombudsman’s Office: Add a specific foster care branch in the ombudsman’s office with a dedicated and knowledgeable staff that deals solely with foster care complaints. Additionally, under that branch, a few staff are dedicated solely to receiving and handling foster youth-only phone calls and complaints.

- School District Policy Change: Training for teachers, school social workers, mental health therapists, and family resource specialists on culturally-informed approaches to responding to perceived potential cases of neglect or abuse

- State Policy Change: Allow foster youth to go to court alone

- State Policy Change: Remove requirement for bio parents to pay for the cost of foster care

- State Policy Change: Pilot providing financial resources (perhaps Universal Basic Income?) to biological parents to help them keep custody of children

- State Policy Change: Increase funding allocation to DCBS to decrease case-load of case workers

- State Policy Change: Mandatory Reporting Law in the state to change what should be called into the hotline

- State Policy: Provide funding for nonprofit organizations for special case management and support for relatives willing to provide kinship care

- Third Sector—Maybe University or Maybe Non-Profit: Provide training directly to youth

- Bill of Rights

- Emotion Regulation

- Inform children of multiple ways to seek help if they experience abuse or neglect in foster care, including case workers, school-teachers, nurses, hotlines, etc.

- Love Notes

- Offer processing and social groups specific to children and adolescents in the foster care system for support and validation

- Offer problem-solving, decision-making, and life planning classes for all youth in the foster care system

- Young Adults—Provide training directly to youth

- Bill of Rights

- Emotion Regulation

- Inform children of multiple ways to seek help if they experience abuse or neglect in foster care, including case workers, school-teachers, nurses, hotlines, etc.

- Love Notes

- Offer processing and social groups specific to children and adolescents in the foster care system for support and validation

- Offer problem-solving, decision-making, and life planning classes for all youth in the foster care system

- Federal Policy Change: Remove timeline for termination of parental rights to allow parents more time to meet requirements-ASFA

- State and Federal Policy change: Advocating for Young Adult/Lived Expert-led Organizations to Receive Federal Funding

References

- Androff, D.K. Narrative healing among victims of violence: The impact of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Fam. Soc. 2018, 93, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, S.L. The role of truth-telling in Indigenous Justice. J. Race Gend. Ethn. 2022, 11, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.; Wilson, R.A. Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: Anthropological perspectives. In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Callan, H., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2923387 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Hirsch, M.B.-J.; MacKenzie, M.; Sesay, M. Measuring the impacts of truth and reconciliation commissions: Placing the global ‘success’ of TRCs in local perspective. Coop. Confl. 2012, 47, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzin, S.C.; Singer, E.; Hokanson, K. Emerging Versus Emancipating: The Transition to Adulthood for Youth in Foster Care. J. Adolesc. Res. 2014, 29, 616–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häggman-Laitila, A.; Salokekkilä, P.; Karki, S. Young people’s preparedness for adult life and coping after foster care: A systematic review of perceptions and experiences in the transition period. Child Youth Care Forum 2019, 48, 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg, F.F. Becoming Adults: Challenges in the Transition to Adult Roles. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2015, 85 (Suppl. S5), S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Morgan, W. Transitioning to Adulthood from Foster Care. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 26, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shane, J.; Heckhausen, J. Optimized engagement across life domains in adult development: Balancing diversity and interdomain consequences. Res. Hum. Dev. 2016, 13, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.; Fonseca, G.; Sotero, L.; Crespo, C.; Relvas, A.P. Family Dynamics During Emerging Adulthood: Reviewing, Integrating, and Challenging the Field. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2020, 12, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.J.; Marcal, K.E.; Zhang, J.; Day, O.; Landsverk, J. Homelessness and aging out of foster care: A national comparison of child welfare-involved adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 77, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, M.; Skyles, A. Racial disproportionality in the child welfare system. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2003, 25, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettlaff, A.J. Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system. In Culturally Responsive Child Welfare Practice; LaLiberte, T., Crudo, T., Ombisa Skallet, H., Day, P., Eds.; Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare, University of Minnesota: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2015; pp. 4–5. Available online: https://cascw.umn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/CW360-Winter2015.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Boyd, R. Racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare. Child Welf. 2022, 100, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cénat, J.M.; McIntee, S.E.; Mukunzi, J.N.; Noorishad, P.G. Overrepresentation of Black children in the child welfare system: A systematic review to understand and better act. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children’s Bureau. The Children’s Bureau AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2022 Estimates as of 2023—No. 30; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://acf.gov/cb/report/afcars-report-30 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Pryce, J.; Yelick, A. Racial disproportionality and disparities among African American children in the child Welfare System. In Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System. Child Maltreatment (Contemporary Issues in Research and Policy), vol 11; Dettlaff, A.J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Butler, A. Intersectionality and the overrepresentation of Black women, children, and families in the child welfare system: A scoping review. J. Public Child Welf. 2024, 18, 1084–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annie, E.; Casey and Kentucky Youth Advocates; Kids Count Data Cent. Child Population Ages 0–19 by Race/Ethnicity in Kentucky. 2025. Available online: https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/11937-child-population-ages-0-19-by-race-ethnicity (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Pryce, J.; Lee, W.; Crowe, E.; Park, D.; McCarthy, M.; Owens, G. A case study in public child welfare: County-level practices that address racial disparity in foster care placement. J. Public Child Welf. 2019, 13, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluke, J.; Jones Harden, B.; Jenkins, M.; Ruehrdanz, A.; Research Synthesis on Child Welfare Disproportionality and Disparities. Papers from a Research Symposium Convened by the Center for the Study of Social Policy and the Annie E. Casey Foundation on Behalf of the Alliance for Racial Equity in Child Welfare. 2010. Available online: https://casala.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Disparities-and-Disproportionality-in-Child-Welfare_An-Analysis-of-the-Research-December-2011-1.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission; Government of South Africa. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report (Vols. 1–5). 1998. Available online: https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea. Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the Republic of Korea. 2010. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truth_and_Reconciliation_Commission_(South_Korea) (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone. Witness to Truth: Report of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 2004. Available online: https://atjhub.csvr.org.za/sierra-leone-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-2002-2004/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Commission for Historical Clarification; United Nations. Guatemala: Memory of Silence. 1999. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23778631 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada’s Residential Schools: The Legacy (Vol. 5); McGill-Queen’s University Press: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Final Report of the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 2015. Available online: https://www.wabanakireach.org/truth_reconciliation (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families (Australia); Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. 1997. Available online: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2312906030 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Yoorrook Justice Commission. Yoorrook for Transformation: Final Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.yoorrook.org.au/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- de Costa, R. Discursive institutions in non-transitional societies: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2017, 38, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avruch, K. Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: Problems in Transitional Justice and the Reconstruction of Identity. Transcult. Psychiatry 2010, 47, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: New considerations. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickreme, E.; Infurna, F.J.; Alajak, K.; Blackie, L.E.R.; Chopik, W.J.; Chung, J.M.; Dorfman, A.; Fleeson, W.; Forgeard, M.J.C.; Frazier, P.; et al. Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. J. Personal. 2020, 89, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.; Graham-Kevan, N.; Robinson, S.; Lowe, M. Trauma characteristics and posttraumatic growth: The mediating role of avoidance coping, intrusive thoughts, and social support. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L. Optimism, Social Support, and Coping Strategies As Factors Contributing to Posttraumatic Growth: A Meta-Analysis. J. Loss Trauma 2009, 14, 364–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioneso, N.A.; Hunter, C.D.; Gobin, R.L.; McNeil Smith, S.; Mendenhall, R.; Neville, H.A. Community Healing and Resistance Through Storytelling: A Framework to Address Racial Trauma in Africana Communities. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grittner, A. Sensory arts-based storytelling as critical reflection: Tales from an online graduate social work classroom. Learn. Landsc. 2021, 14, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J.; McGannon, K.R.; Zehntner, C. Arts-based methods as a trauma-informed approach to research: Making trauma visible and limiting harm. Methods Psychol. 2024, 10, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer-Wackerly, A.L.; Coffey, J.; Wheeler, L.A.; Emmerich, C.; Gonzalez, L.; Chaidez, V.; Acosta, L.; Tippens, J.A.; Wahed, K.; Chai, W. Centering U.S. Rural, immigrant latinx adolescent voices through narrative mapping: Exploring a novel approach to communicated narrative sense-making. Health Commun. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmire, D.A.; Rankin, N.E.; Gorham, S.R.; Eggleston, D.T.; French, C.A.; Lodge, E.E.; Grimm, D.R. Psychological and autonomic effects of art making in college-aged students. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boydell, K.; Gladstone, B.M.; Volpe, T.; Allemang, B.; Stasiulis, E. The Production and Dissemination of Knowledge: A Scoping Review of Arts-Based Health Research. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2012, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.L.; Sonke, J.; Rodriguez, A.K. An Evidence-Based Framework for the Use of Arts and Culture in Public Health. Health Promot. Pract. 2024, 26, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, M.E. PAR-Map. 2009. Available online: https://actionresearch.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/PAR-Map.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Feekery, A. The 7 C’s framework for participatory action research: Inducting novice participant-researchers. Educ. Action Res. 2023, 32, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranis, K. The Little Book of Circle Processes: A New/Old Approach to Peacemaking; Good Books: Surrey, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, T. Artwork: System vs. growth. Fam. Justice J. 2024, 2024, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.; Ngunjiri, F.W.; Hernandez, K.C. Collaborative Autoethnography; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lapadat, J.C. Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A.; Kosecoff, J.; Chassin, M.; Brook, R.H. Consensus methods: Characteristics and guidelines for use. Am. J. Public Health 1984, 74, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin-Sahin, D.; Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Bolster-Foucault, C.; Champoux-Pellegrin, J.; Rojas-Rozo, L.; Quesnel-Vallée, A.; Vedel, I. Building timely consensus among diverse stakeholders: An adapted nominal group technique. Ann. Fam. Med. 2024, 22, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, D.B.; Cañedo-Ayala, M.; Turner, K.A.; Gumuchian, S.T.; Malcarne, V.L.; Hagedoorn, M.; Thombs, B.D.; Scleroderma Caregiver Advisory Team. Use of the nominal group technique to identify stakeholder priorities and inform survey development: An example with informal caregivers of people with scleroderma. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. Methods for determining deliberative consensus. In Expert Consensus in Science; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N.; Hess, S.A.; Ladany, N. Consensual qualitative research: An update. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnapalan, S.; Haldane, V. We go farther together: Practical steps towards conducting a collaborative autoethnographic study. JBI Evid. Implement. 2022, 20, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.W.; Rackers, H.; Meyer, A.; McKenzie, K.J.; Malm, K.; Sepulveda, K.; Heath, C. Co-Regulation as a Support for Older Youth in the Context of Foster Care: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Prev. Sci. 2023, 24, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, B.F.; Barbee, A.P. Psychoeducation for Trauma in Youth: A Preliminary Trial on the Mind Matters Program. Child Welf. 2022, in press.

- Barbee, A.P.; Cunningham, M.R.; Antle, B.F.; Langley, C.N. Impact of a relationship-based intervention, Love Notes, on teen pregnancy prevention. Fam. Relat. 2023, 72, 2569–2588. [Google Scholar]

- Barbee, A.P.; Cunningham, M.R.; van Zyl, M.A.; Antle, B.F.; Langley, C.N. Impact of two teen pregnancy prevention interventions on condom and birth control use: A three-arm, cluster randomized control trial. Am. J. Public Health Spec. Suppl. Teen Pregnancy Prev. 2016, 106, S85–S90. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Harden, B.; Simons, C.; Johnson-Motoyama, M.; Barth, R. The child maltreatment prevention landscape: Where are we now, and where should we go? Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2021, 692, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Negash, T.; Steinman, K.J. Child maltreatment prevention strategies and needs. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3572–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentucky Revised Statute #600.020. Legal Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect. 2022. Available online: https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=56525 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Audulv, Å.; Hall, E.O.C.; Kneck, Å.; Westergren, T.; Fegran, L.; Pedersen, M.K.; Aagaard, H.; Dam, K.L.; Ludvigsen, M.S. Qualitative longitudinal research in health research: A method study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2022, 22, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engage for Equity Research Team. Promising Practices of CBPR and Community Engaged Research Partnerships; University of New Mexico: Albuquerque, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.; Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Magarati, M.; Burgess, E.; Boursaw, B.; Koegel, P. Engage for Equity: Development of community-based participatory research tools. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, W.; Sugrue, E.P.; Calhoon, M. Moral injury among child professionals: Implications for the ethical treatment and retention of workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent-Goodley, T.; Fairfax, C.N.; Carlton-LaNey, I. The significance of African-centered social work for social work practice. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2017, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, D.F. Key Concepts, Theories, and Issues in African/Black Psychology: A View From the Bridge. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 722–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target System | Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | DCBS and State | Lived Expert-led Organizations to Receive Funding from State and Federal Services to Provide Training to Youth in Foster Care Related to their Rights, Life-Planning, Mental Health Promotion, and Healthy Relationships |

| 2. | DCBS | Avoid using pathologizing labels in youth case files |

| 3. | DCBS | Remove adoption as the priority permanency plan; Replace with Reunification with Biological Family or Independence |

| 4. | State | Pilot providing financial resources to biological parents to help them keep custody of children (use for foster care to give family resources they need to keep children safe and at home) |

| 5. | State | Create a Foster Care Branch in the ombudsman’s office—not controlled or regulated by DCBS |

| 6. | DCBS | Caseworkers to monitor that parents follow the normalcy laws during the monthly meetings & Allow youth to identify up to 2 or 3 extended or fictive kin whom they are supported by and need to stay in touch with |

| 7. | DCBS | Require caseworkers give as much notice to the child as possible of an impending move; If an appropriate reason exists for why this cannot be done, require documentation of that reason; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document notice and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR consequences, if not completed consistently |

| 8. | DCBS | Require that case workers solicit and document child preferences for permanency planning; Supervisors monitor that caseworkers document that they include children in permanency planning, and provide feedback to caseworkers, with potential HR consequences, if not completed consistently |

| 9. | DCBS | Require module in cultural sensitivity, cultural competence, and racial trauma as part of foster parent training (e.g., values, different grooming and personal care products, etc.) |

| 10. | DCBS | Provide case management and support for biological parents to help them meet the goals in their care plan (in addition to the traditional substance use and mental health treatment, offer job training, job placement, connection to mutual aid collaboratives, biological parent advocacy organizations in the community, etc.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sterrett-Hong, E.; Merkel-Holguin, L.; Thornton, N.; Barbee, A.; Wright, G.; Dawson, E.; Galloway, C.; Angelini, C.; Humphrey, T. “It Was an Opportunity to Create Our Story in a Way in Which We Viewed It”: Arts-Based Truth-Telling by Black American Young Adult Alumni of the Child Welfare System. Adolescents 2025, 5, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040073

Sterrett-Hong E, Merkel-Holguin L, Thornton N, Barbee A, Wright G, Dawson E, Galloway C, Angelini C, Humphrey T. “It Was an Opportunity to Create Our Story in a Way in Which We Viewed It”: Arts-Based Truth-Telling by Black American Young Adult Alumni of the Child Welfare System. Adolescents. 2025; 5(4):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040073

Chicago/Turabian StyleSterrett-Hong, Emma, Lisa Merkel-Holguin, Nikki Thornton, Anita Barbee, Glenda Wright, Eltuan Dawson, Cameron Galloway, Chyna Angelini, and Tia Humphrey. 2025. "“It Was an Opportunity to Create Our Story in a Way in Which We Viewed It”: Arts-Based Truth-Telling by Black American Young Adult Alumni of the Child Welfare System" Adolescents 5, no. 4: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040073

APA StyleSterrett-Hong, E., Merkel-Holguin, L., Thornton, N., Barbee, A., Wright, G., Dawson, E., Galloway, C., Angelini, C., & Humphrey, T. (2025). “It Was an Opportunity to Create Our Story in a Way in Which We Viewed It”: Arts-Based Truth-Telling by Black American Young Adult Alumni of the Child Welfare System. Adolescents, 5(4), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040073