Visual Representations of Happiness in Portuguese Adolescents †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Happiness and Adolescents

1.2. Arts-Informed/Creative Methods and Visual Research

1.3. Draw-and-Write Technique

1.4. The iSquare Protocol

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

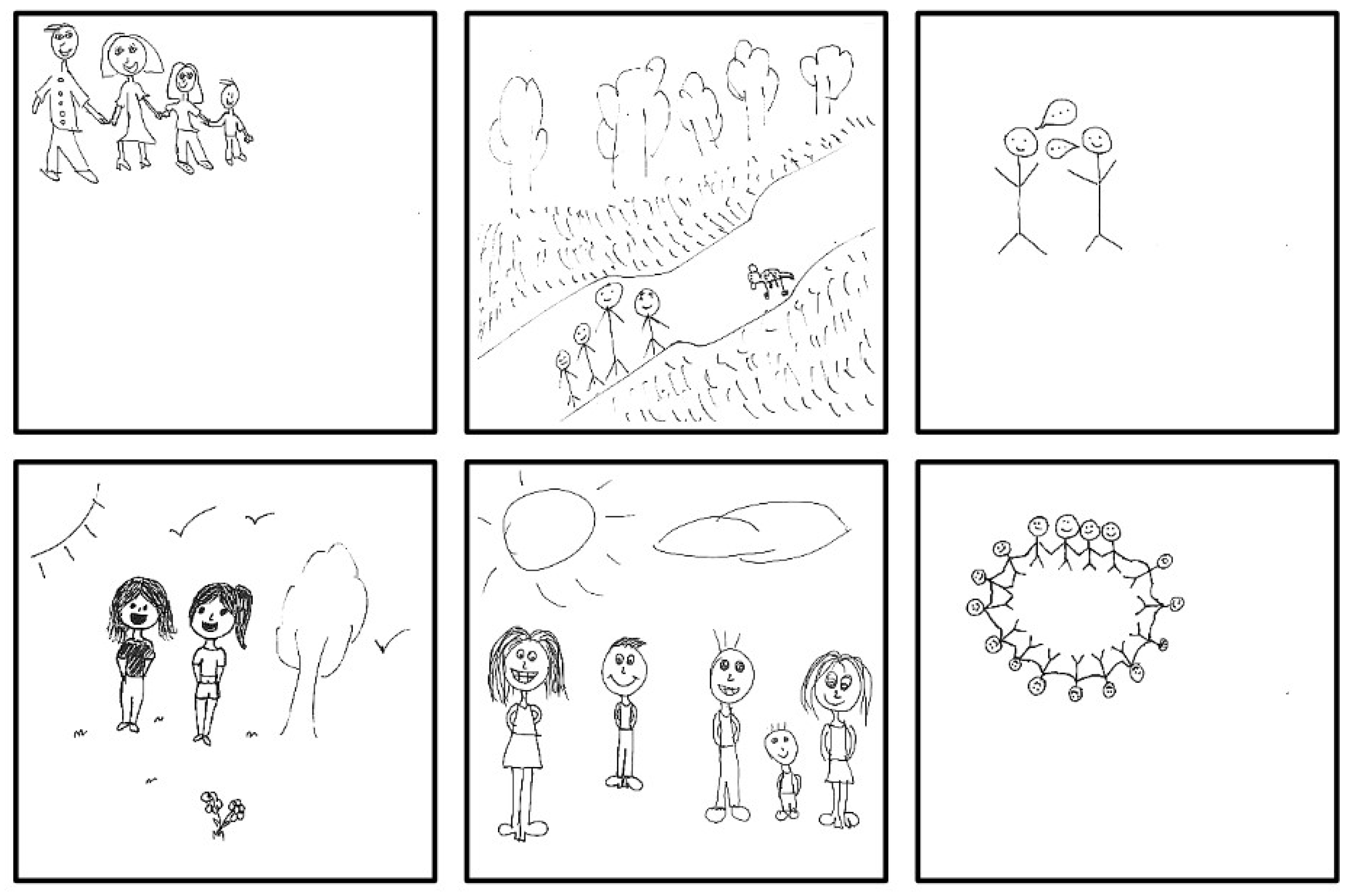

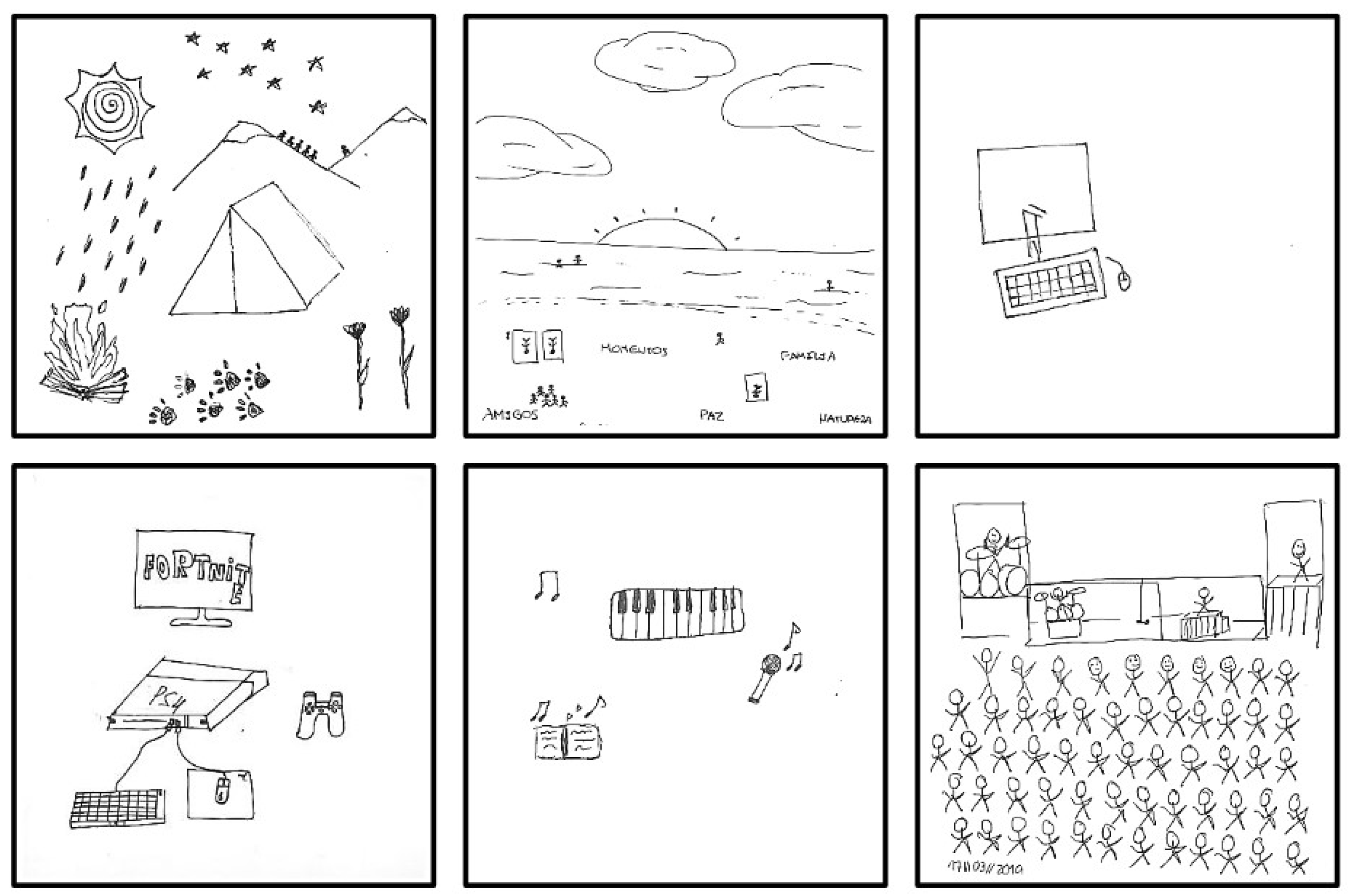

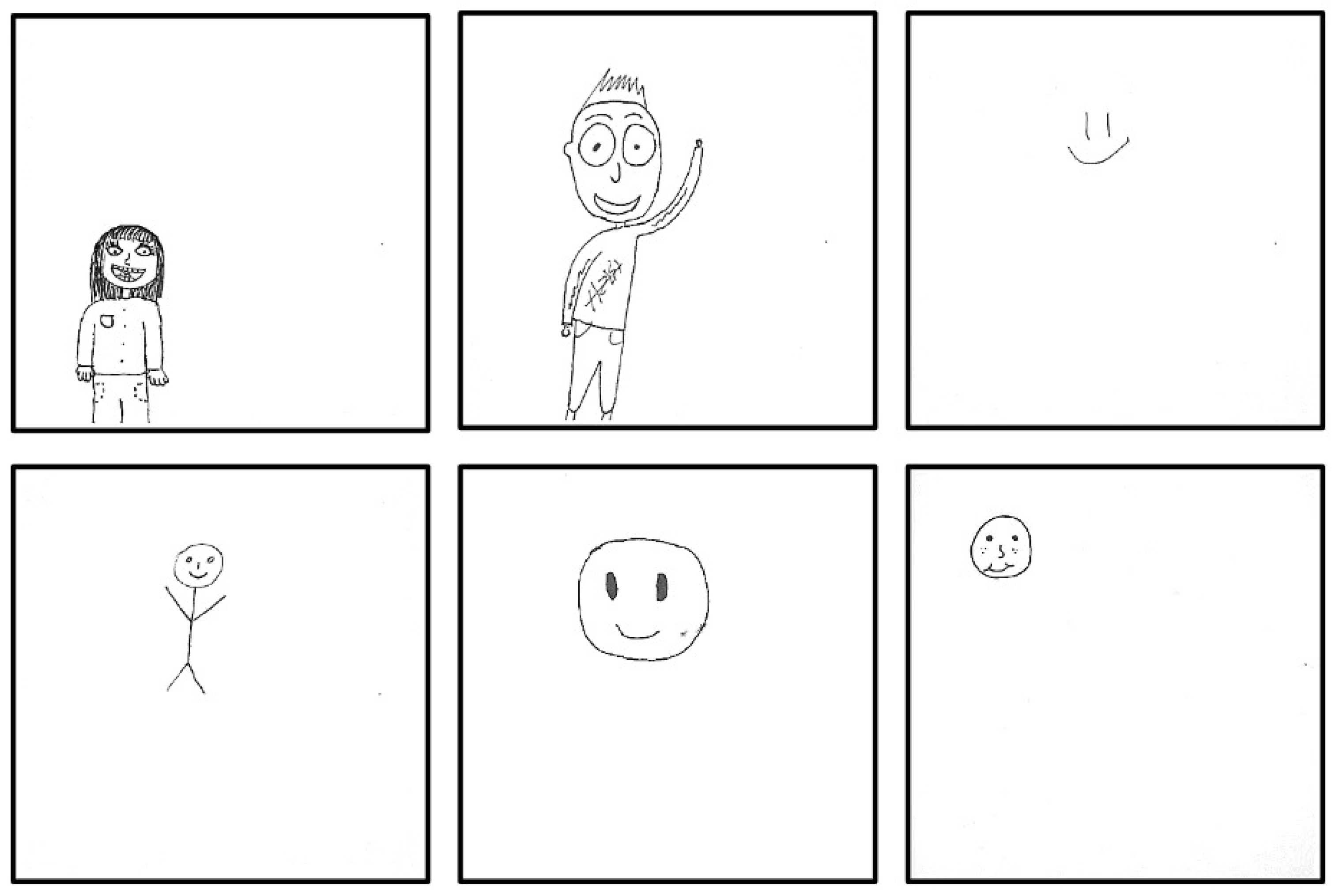

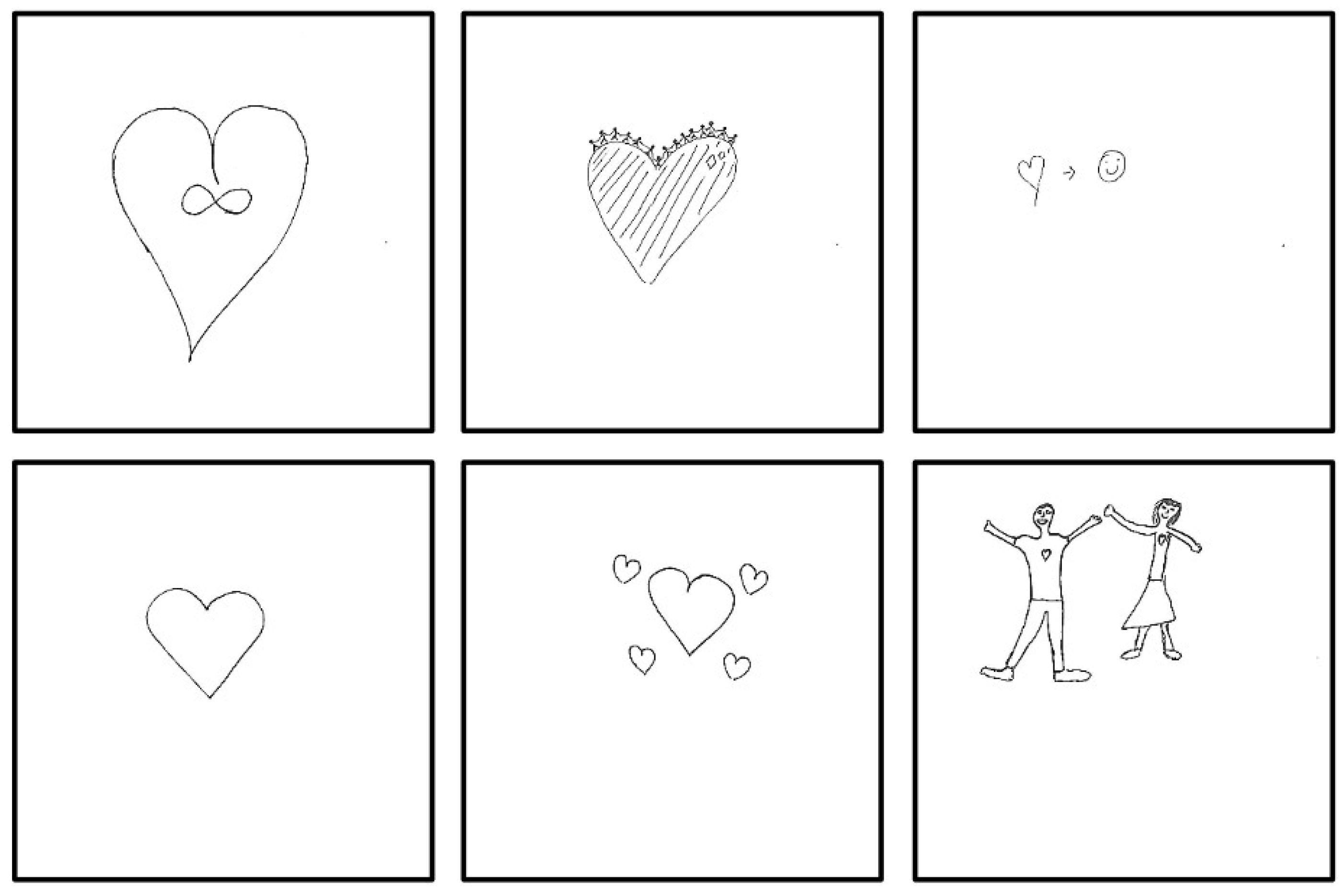

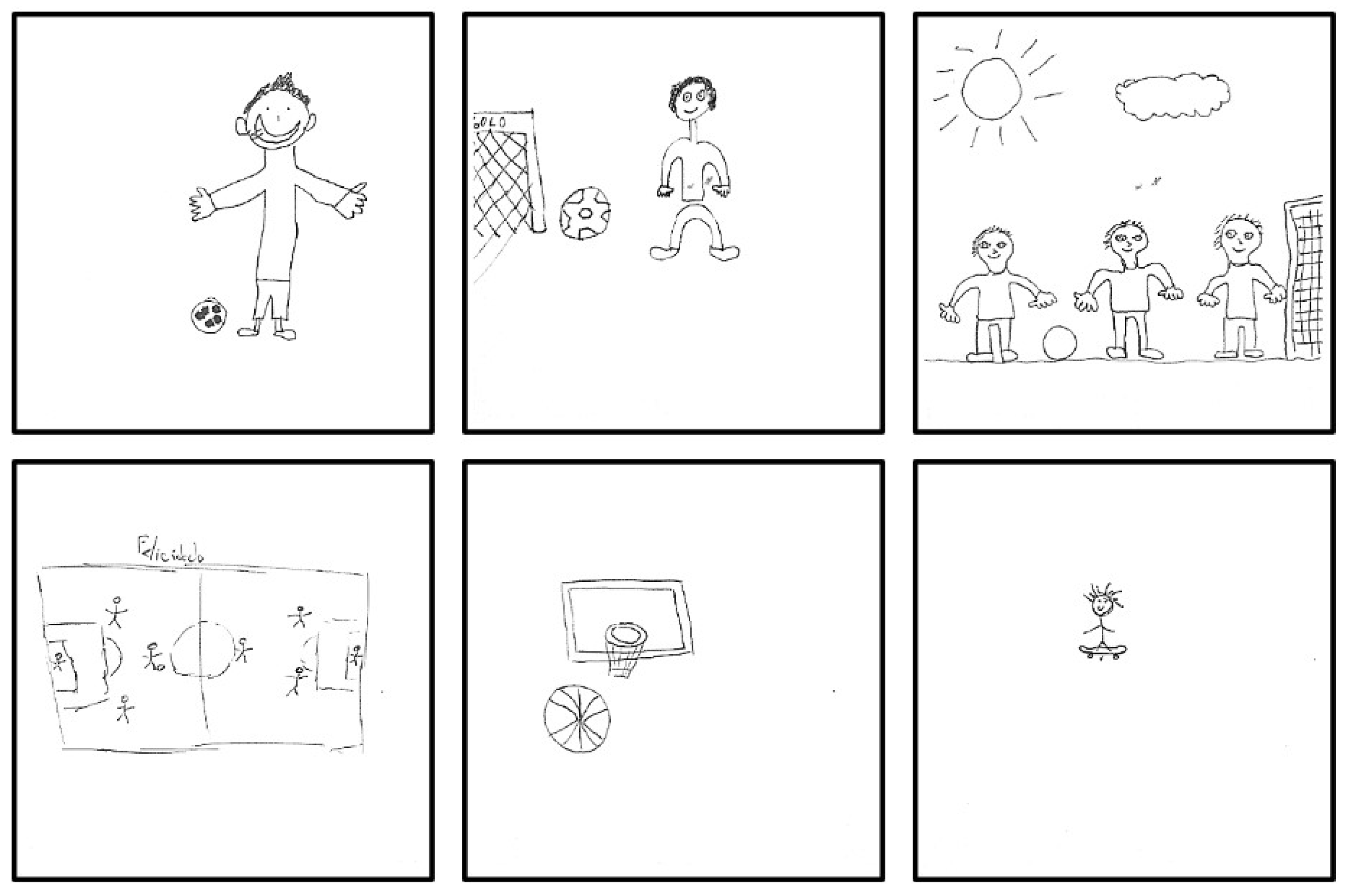

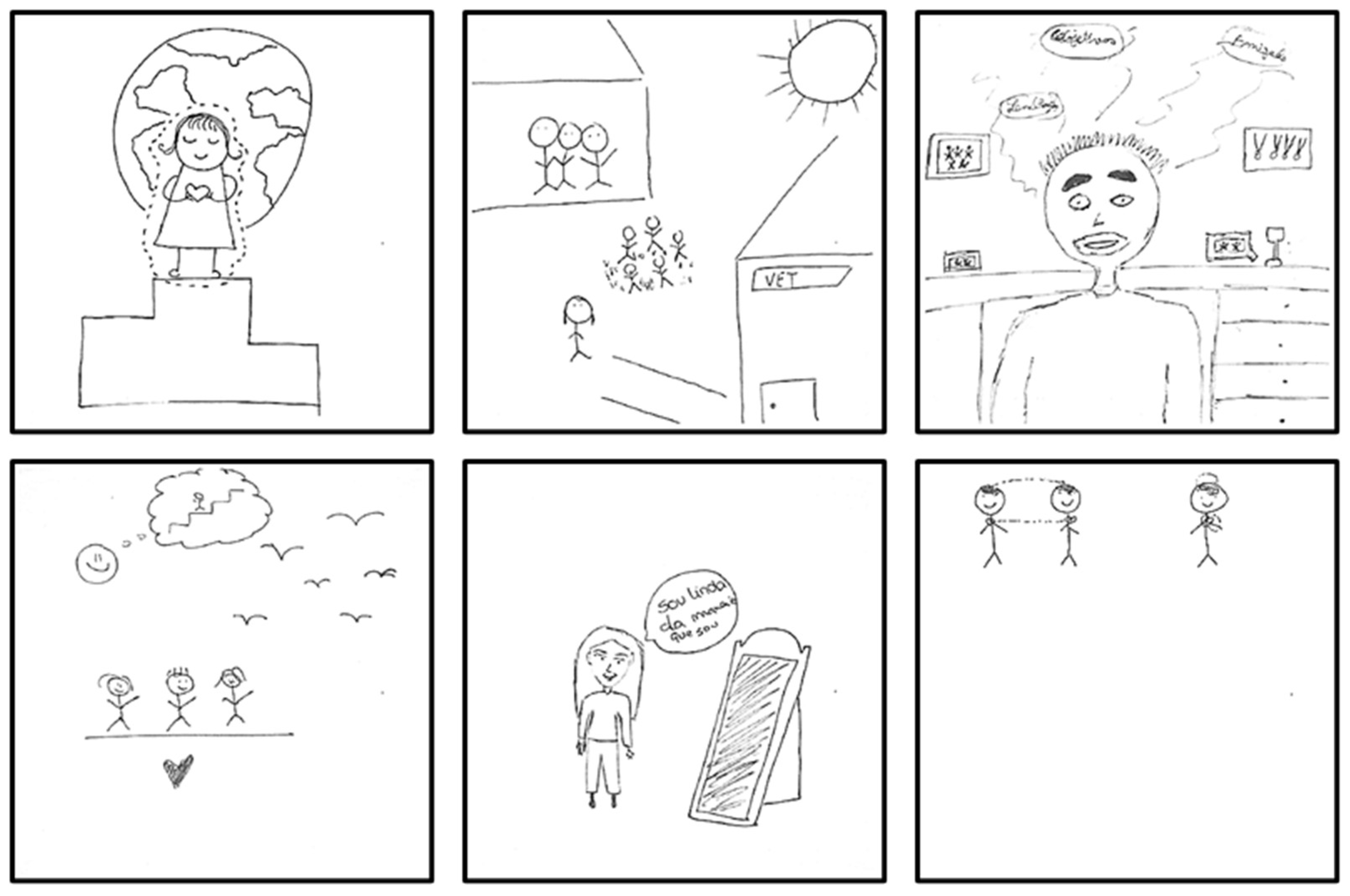

3.1. Qualitative Analysis: Thematic Analysis

3.2. Thematic Analysis According to Age

4. Discussion

4.1. Contents and Meanings of the Happiness Drawings

4.2. Older Versus Younger Adolescent’s Drawings

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnston, B.R.; Colson, E.; Falk, D.; St John, G.; Bodley, J.H.; McCay, B.J.; Wali, A.; Nordstrom, C.; Slymovics, S. On Happiness. Am. Anthropol. 2012, 114, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieda, A.; Hirschfeld, G.; Schönfeld, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. Universal happiness? Cross-cultural measurement invariance of scales assessing positive mental health. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 29, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, W.C. An Introduction to Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Thomson/Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Csíkszentmihályi, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, I.S. Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, T.; Tavares, D. Influência da autoestima, da regulação emocional e do gênero no bem-estar subjetivo e psicológico de adolescentes. Rev. Psiquiatr. Clín. 2011, 38, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Fave, A.; Brdar, I.; Freire, T.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Wissing, M.P. The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: Qualitative and quantitative findings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 100, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N. The role of subjective well-being in positive youth development. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2004, 591, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delle Fave, A.; Brdar, I.; Wissing, M.P.; Araujo, U.; Castro Solano, A.; Freire, T.; Del Rocio Hernandez-Pozo, M.; Jose, P.; Martos, T.; Nafstad, H.E.; et al. Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galambos, N.L.; Krahn, H.J.; Johnson, M.D.; Lachman, M.E. The U-shape of happiness across the life course: Expanding the discussion. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, S. Using visual images in research. In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues; Knowles, J., Cole, A., Eds.; Sage Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hartel, J. An arts-informed study of information using the draw-and-write technique. Assoc. Info. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 1349–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E.; Flèche, S.; Layard, R.; Powdthavee, N.; Ward, G. The Origins of Happiness: The Science of Well-Being over the Life Course; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Questions on happiness: Classical topics, modern answers, blind spots. In Subjective Well-Being: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Strack, F., Argyle, M., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Moneta, G.B.; Schneider, B.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. A longitudinal study of the self-concept and experiential components of self-worth and affect across adolescence. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2001, 5, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Hunter, J. Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. J. Happiness Stud. 2003, 4, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, B.; Sánchez, J.; Gummerum, M. Children’s and adolescents’ conceptions of happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 2431–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, T.; Zenhas, F.; Tavares, D.; Iglésias, C. Felicidade hedónica e eudaimónica: Um estudo com adolescentes portugueses. Análise Psicol. 2014, 31, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Gunn, J.; Petersen, A.C. Studying the emergence of depression and depressive symptoms during adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1991, 20, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Furnham, A. Personality, self-esteem, and demographic predictions of happiness and depression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Tay, L. A scientific review of the remarkable benefits of happiness for successful and healthy living. In Psychological Wellbeing; Adler, A., Unanue, W., Osin, E., Alkire, S., Eds.; The Centre for Bhutan Studies and GNH: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss, J.; Smollar, J. Adolescent Relations with Mothers, Fathers, and Friends; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, A.L.; Knowles, J.G. Arts-informed research. In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues; Knowles, J.G., Cole, A.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mannay, D. Visual, Narrative, and Creative Research Methods: Application, Reflection, and Ethics, 1st ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hartel, J.; Thomson, L. Visual approaches and photography for the study of immediate information space. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 2011, 62, 2214–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington DC, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reavey, P. The return to experience: Psychology and the visual. In A Handbook of Visual Methods in Psychology: Using and Interpreting Images in Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, M.; Denov, M.; Khan, F.; Linds, W.; Akesson, B. Research as intervention? Exploring the health and well-being of children and youth facing global adversity through participatory visual methods. In Participatory Visual Methodologies in Global Public Health; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Theron, L.; Mitchell, C.; Smith, A.; Stuart, J. Picturing Research: Drawing as Visual Methodology; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hartel, J. Draw-and-Write Techniques. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; Atkinson, S., Delamont, A., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J.W., Williams, R.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridmore, P.; Bendelow, G. Images of health: Exploring beliefs of children using the “draw-and-write” technique. Health Educ. J. 1995, 54, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousta, S.; Vigliocco, G.; Vinson, D.; Andrews, A. Happiness is an abstract word: The role of affect in abstract knowledge representation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 29 July–1 August 2009; Volume 31, pp. 1115–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, S.; Mitchell, C. That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Like a Teacher! Interrogating Images and Identity in Popular Culture; Falmer Press: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bradding, A.; Horstman, M. Using the write and draw technique with children. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 1999, 3, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Gabhainn, S.; Kelleher, C. The sensitivity of the draw and write technique. Health Educ. 2002, 102, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, Z.R.; Parnell, D.; Stratton, G.; Ridgers, N.D. Learning from the experts: Exploring playground experience and activities using a write and draw technique. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasarraju, R.; Nirmala, S.; Kolli, N.R.; Inthihas, S.; Nuvvula, S. Application of write-and-draw technique in pediatric dentistry: A pilot study. Int. J. Pedod. Rehabil. 2016, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üztemur, S.; Dinç, E.; Ekinci, H. Using draw-write-tell to explore middle school students’ conceptions of the social studies course. Turk. Online J. Qual. Inq. 2020, 11, 280–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Meng, Y.; Chen, J. Multidimensional mental representations of natural environment among Chinese pre-adolescents via draw-and-write mapping. People Nat. 2024, 6, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, S.; Colantonio, A.; Leccia, S.; Marzoli, I.; Puddu, E.; Testa, I. Developing the use of visual representations to explain basic astronomy phenomena. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2018, 14, 010145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Miura, Y.; Manning, C.D.; Langlotz, C.P. Contrastive learning of medical visual representations from paired images and text. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 182, 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Debrenti, E. Visual representations in mathematics teaching: An experiment with students. Acta Didact. Napoc. 2015, 8, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pitta-Pantazi, D.; Christou, C.; Pittalis, M. Number teaching and learning. In Encyclopedia of Mathematics Education, 2nd ed.; Lerman, S., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2020; pp. 645–654. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.P. Visual representations in science education: The influence of prior knowledge and cognitive load theory on instructional design principles. Sci. Educ. 2006, 90, 1073–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, J. Visual literacy and science communication. Sci. Commun. 1999, 20, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.-M.; Bowen, G.M.; McGinn, M.K. Differences in graph-related practices between high school biology textbooks and scientific ecology journals. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1999, 36, 977–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, J.; Noone, R.; Oh, C.; Power, S.; Danzanov, P.; Kelly, B. The iSquare protocol: Combining research, art, and pedagogy through the draw-and-write technique. Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glauch, N.; Choi, D.S.; Herman, G. How engineering students use domain knowledge when problem-solving using different visual representations. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 109, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, S.E.; Scheiter, K. Learning by drawing visual representations: Potential, purposes, and practical implications. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 30, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieba, A. Visual representation of happiness: A sociosemiotic perspective on stock photography. Soc. Semiot. 2023, 33, 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paola, J.; Hakoköngäs, E.J.; Hakanen, J.J. #Happy: Constructing and sharing everyday understandings of happiness on Instagram. Hum. Arenas 2022, 5, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Zimet, G.; Segel, S. The concept of happiness as conveyed in visual representations: Analysis of the work of early childhood educators. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2014, 2, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hartel, J. Adventures in visual methods. Vis. Methodol. 2017, 5, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, T.; Teixeira, A.; Vilas Boas, D. Subjective Happiness Scale: Validation for Portuguese adolescents. Psic. Saúde Doenças 2022, 23, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K. Stages of Adolescence. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Brown, B.B., Prinstein, M.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumeboonsuke, V. Parents or peers, wealth or warmth? The impact of social support, wealth, and a positive outlook on self-efficacy and happiness. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Zumbo, B.D. Life satisfaction in early adolescence: Personal, neighborhood, school, family, and peer influences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartko, W.T.; Eccles, J.S. Adolescent participation in structured and unstructured activities: A person-oriented analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Valdez, J.P.M. Exploring Filipino adolescents’ conception of happiness. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2012, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, C. The relationships among attitude towards sports, loneliness and happiness in adolescents. Universal J. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutounchian, M. The Right of Happiness for Children: The Manifestation of Human Rights in Modern Times. Q. J. Interdiscip. Leg. Res. 2020, 1, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Cricchio, M.G.; Costa, S.; Liga, F. Adolescents’ Well-Being: The Role of Basic Needs Fulfilment in Family Context. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 39, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martela, F.; Lehmus-Sun, A.; Parker, P.D.; Pessi, A.B.; Ryan, R.M. Needs and Well-Being Across Europe: Basic Psychological Needs Are Closely Connected With Well-Being, Meaning, and Symptoms of Depression in 27 European Countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2023, 14, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, N.; Soenens, B.; Brenning, K.; Vansteenkiste, M. Adolescents as Active Managers of Their Own Psychological Needs: The Role of Psychological Need Crafting in Adolescents’ Mental Health. J. Adolesc. 2021, 88, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westera, J.J.; Van Der Molen, M.J.; Schuengel, C. Basic Psychological Needs and Mental Health in Adolescents with a Mild to Borderline Intellectual Disability. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2024, 17, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, A.; Smetana, J.G. Social Cognitive Development and Adolescent Civic Engagement. In Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth, 1st ed.; Sherrod, L.R., Torney-Purta, J., Flanagan, C.A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mužík, M.; Šerek, J.; Juhová, D.S. The Effect of Civic Engagement on Different Dimensions of Well-Being in Youth: A Scoping Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2025, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimenko, S.; Serdiuk, L. Psychological Potential of Personal Self-Realization. Soc. Welf. Interdiscip. Approach 2016, 6, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjell, O.N.E. Sustainable Well-Being: A Potential Synergy between Sustainability and Well-Being Research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D.; Montserrat, C.; Malo, S.; González, M.; Casas, F.; Crous, G. Subjective well-being: What do adolescents say? Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo, S.; Navarro, D.; Casas, F. The use of audiovisual media in adolescence and its relationship with subjective well-being: A qualitative analysis from an intergenerational and gender perspective. Athenea Digit. 2012, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carreno, D.F.; Eisenbeck, N.; Pérez-Escobar, J.A.; García-Montes, J.M. Inner Harmony as an Essential Facet of Well-Being: A Multinational Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-Behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.P. Cognitive Development During Adolescence. In Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence, 1st ed.; Adams, G.R., Berzonsky, M.D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitt, W.; Hummel, J. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development; Valdosta State University: Valdosta, GA, USA, 2003; Available online: http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/cognition/piaget.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Malik, F.; Marwaha, R. Cognitive Development; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, R. Conservation acquisition: A problem of learning to attend to relevant attributes. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1969, 7, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, J.A. Adolescence as a Pivotal Period for Emotion Regulation Development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.M.; Clark, H.M.; Haraden, D.A.; Young, J.F.; Hankin, B.L. Affective Development from Middle Childhood to Late Adolescence: Trajectories of Mean-Level Change in Negative and Positive Affect. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1550–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitulić, H.S. The Development of Understanding of Basic Emotions from Middle Childhood to Adolescence. Stud. Psychol. 2009, 51, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- INE. People—2023; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Themes | 11 n = 1 | 12 n = 46 | 13 n = 34 | 14 n = 60 | 15 n = 44 | 16 n = 68 | 17 n = 64 | 18 n = 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People | 0.51 | 11.73 | 8.67 | 14.80 | 14.29 | 20.41 | 23.98 | 5.61 |

| Hobbies | 0 | 6.82 | 6.82 | 11.36 | 13.64 | 19.32 | 37.50 | 4.55 |

| Love | 1.27 | 3.80 | 8.86 | 22.78 | 12.66 | 25.32 | 24.05 | 1.27 |

| Smile | 0 | 15.79 | 11.84 | 26.32 | 13.16 | 21.05 | 9.21 | 2.63 |

| Sports | 0 | 22.83 | 4.55 | 11.36 | 6.82 | 25.00 | 29.55 | 0 |

| Basic Needs | 0 | 5.56 | 8.33 | 22.22 | 8.33 | 22.22 | 30.56 | 2.78 |

| Inner Harmony | 0 | 0 | 4.00 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 32.00 | 36.00 | 0 |

| Human Rights and Equality | 6.25 | 12.50 | 25.00 | 6.25 | 12.50 | 18.75 | 18.75 | 0 |

| Remaining | 0 | 0 | 6.25 | 25.00 | 18.75 | 31.25 | 12.50 | 6.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freire, T.; Ramos, A.; Raposo, B.; Hartel, J. Visual Representations of Happiness in Portuguese Adolescents. Adolescents 2025, 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020026

Freire T, Ramos A, Raposo B, Hartel J. Visual Representations of Happiness in Portuguese Adolescents. Adolescents. 2025; 5(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreire, Teresa, Andreia Ramos, Beatriz Raposo, and Jenna Hartel. 2025. "Visual Representations of Happiness in Portuguese Adolescents" Adolescents 5, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020026

APA StyleFreire, T., Ramos, A., Raposo, B., & Hartel, J. (2025). Visual Representations of Happiness in Portuguese Adolescents. Adolescents, 5(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020026