1. Introduction

Exclusionary discipline practices (e.g., discipline referrals, both in- and out-of-school suspensions, detention, expulsion) are frequently used in school systems to deal with contextually inappropriate behaviors [

1]. These practices have been well documented to negatively impact student outcomes, leading to increases in absenteeism, repeating grades [

2,

3], academic struggles [

4,

5,

6,

7], decreased high school graduation rates [

8,

9,

10], and increased involvement with the juvenile and adult justice systems [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, the frequent use of exclusionary discipline with middle school-aged adolescents has been found to have further negative impacts during an already fragile stage of development [

15]. Adolescence, particularly during middle school, is a critical developmental stage marked by heightened sensitivity to peer relationships, an increased focus on identity formation, and growing susceptibility to feelings of embarrassment and self-consciousness, all of which play a significant role in shaping students’ connectedness to school and their performance in academic settings [

16,

17,

18]. Disruptions caused by exclusionary discipline during adolescence can have a lasting effect, as middle school-aged students are more likely to feel disconnected from schools and engage less with learning, further impacting their trajectories [

19,

20]. Exclusionary discipline practices have also been found to be disproportionately used with students who identify as Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC), those receiving special education services, living in poverty, and LGBTQIA+ youth [

21,

22,

23,

24]. For marginalized youth, the compounded stress of experiencing exclusion and stigma exacerbates feelings of disconnectedness to school, further hindering their outcomes [

25,

26]. Despite the vast amount of evidence showing the inequity and negative effects of exclusionary discipline, few studies give students the chance to describe firsthand the impact it has on their lives and what could be done differently to support their growth instead. Understanding the unique perspectives of middle school students is essential, as their insights can provide critical guidance on how to shape supportive environments. This study aimed to address these gaps by centering the perspectives of middle school students and examining the implementation of ISLA as an inclusive alternative to exclusionary discipline. By focusing on middle school—a critical stage of development—this research provides actionable recommendations for creating supportive environments that promote equity and belonging.

1.1. Students’ Perspectives on the Impact of Exclusionary Discipline

The number of times a student is excluded from the learning environment affects the perception students have of school and the quality of their school life [

20,

27,

28,

29], as well as their academic, social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes [

30,

31,

32]. For instance, a study using a sample of over 30,000 secondary students demonstrated that students who were suspended at least once were more likely to perceive fairness, student–teacher relationships, and engagement and safety in schools negatively in comparison to students who were not suspended [

20]. Schools identified by students as being indifferent towards their needs, due to a lack of supportive structures and low demands placed on them, also had higher rates of exclusion [

33]. As confirmed by Feuerborn et al. [

29], exclusionary discipline practices can undermine students’ perceptions of a safe school climate and positive relationships between students and teachers. Thus, it seems exclusion can influence students to feel unsupported by educators or perceive schools as unfair.

Providing opportunities for students to share their stories is crucial for the development of a welcoming school environment, particularly for underserved students [

34]. In a series of interviews conducted by Kennedy-Lewis and Murphy [

35], students who received between one and six suspensions identified a cycle of exclusion that led teachers to negatively label their behavior as a character flaw. Students perceived that their prior exclusionary punishments forged a label of “badness” that followed their educational career and created a presumption of guilt that reinforced an iterative cycle of physical exclusion [

35]. This physical exclusion continued for students who tried integrating back into the school system after being incarcerated [

36]. Additionally, a study conducting focus groups with more than 70 Black and Brown middle schoolers identified common themes in the way this group perceived teachers’ discipline practices based on their experience [

37]. This group reported experiencing feelings of being singled out by teachers when it came to how they were disciplined, reprimanded without clear justification, and intimidated by teachers to have them behave appropriately in class [

37].

1.2. Alternatives to Exclusion as Voiced by Students

Incorporating student voices into school discipline systems is a relatively new approach to promoting equity, autonomy, and self-determination. As an expression of values, opinions, beliefs, and perspectives, student voice can be used to inform changes to policies, instruction, and practices [

38,

39]. According to Mitra and Gross’s [

40] pyramid, student voice begins with expression and consultation and progresses towards activism and leadership. As one moves up the pyramid, students have increased power, autonomy, and collaboration opportunities with adults. This creates space for co-planning and shared empowerment over outcomes. However, there is limited research on incorporating student voice into the transformation of school discipline systems.

Besides outcomes related to class, school, and district-wide initiatives, outcomes can also be related to larger constructs like school climate, teacher–student relationships, and exclusionary discipline. Surveys, interviews, focus groups, and social validity measures are all common methods of measuring student perspectives on outcomes of interest (for review, see [

38]). Allowing students to share their powerful stories, speak truth to injustice, and bring awareness towards alternatives to exclusion can be a tool for the disruption of inequitable systems. Examples of this can be seen in Annamma et al. [

41], who interviewed girls of color about their experiences with discipline disparities and found differences in the way teachers behaved with them in comparison to their peers when acknowledging students for their academic efforts or meeting behavioral expectations. Their stories informed reflective questions suggested by these authors, who encourage educators to reflect upon the equitable use of acknowledgement practices. For example, Feuerborn et al. [

29] used a more formal tool to access student perspectives on positive behavioral intervention supports (PBIS) and their association with school climate, and found that adults’ acknowledgment systems enhanced students’ positive experiences in school. Further, Gardner et al. [

36] found that formerly incarcerated youth who experienced resistance to reentry reported that having positive relationships with people in schools allowed them to feel safe and focus on their education. In order to achieve equity in education, more research capturing the input of students is needed to transform school discipline. This will allow initiatives to be effective, responsive to students’ needs, and implemented with fidelity.

1.3. A Community-Informed Alternative: The Inclusive Skill-Building Learning Approach

ISLA is a preventative and instructional alternative to exclusionary discipline that promotes positive student–teacher relationships by improving teacher and administrator practices and school systems and provides equitable skill-building supports to improve student social and behavioral problem-solving [

42]. ISLA begins with universal prevention, incorporating positive and proactive classroom strategies for all students, and provides additional targeted support for those who need it [

42]. Grounded in social learning theory, ISLA highlights that behavior is shaped through modeling and instruction, with environmental factors and teaching quality playing a key role in determining how and when behaviors occur [

43]. By systematically teaching and reinforcing new prosocial behaviors while reducing undesirable ones, ISLA fosters an environment that enhances educators’ skills and creates a more welcoming, supportive, and inclusive educational setting.

ISLA was piloted in two middle schools in a small city in the Pacific Northwest region, similar to the schools in this study, with enrollment of around 470 students and demographic populations that were predominantly 60% white and 25% Latino/a/e/x on average. ISLA was refined using student and staff feedback after its pilot implementation to improve the intervention’s contextual fit before further implementation in middle schools within the same school district [

44]. Specifically, 26 members of a design team consisting of district coaches, school administrators, general education and special education teachers, educational assistants, and instructional coaches met quarterly to develop a pilot intervention that was implemented throughout that school year and evaluated by 53 staff members and 23 eighth-grade students in May and June. Their feedback was analyzed and used to inform changes to the intervention. A total of five themes emerged across the student focus groups, feedback from the design team, and staff input: (a) relationship building, (b) classroom prevention, (c) respectful corrections, (d) ISLA materials, and (e) communication with staff. Students commented on macrolevel improvements to school culture and staff members commented on specific ISLA systems and practices to improve these in their schools [

44]. Their input is summarized below, along with the next steps implemented the following school year.

According to the premise that all students should receive teacher support regardless of circumstances, staff and students identified ways to support stronger connections through relationship-building activities. Regarding classroom prevention, design team members and staff spoke to the need for function-based thinking, problem-solving, and prevention strategies. As for students, they noted the positive effects of teachers who incorporated movement breaks and other self-regulatory strategies in the classroom. In addition, students emphasized the benefits of teachers correcting them respectfully and keeping them in the classroom rather than sending them out. By respectful corrections, students spoke of teachers who remained calm, neutral, and discrete. On the other hand, staff emphasized the importance of making amends between students and teachers on the same day so students could get back to learning, and for debriefing of a situation to remain effective by remaining short. Nonetheless, they acknowledged the importance for students to be allowed to calm down before engaging in opportunities for skill-building and reconnection conversation with the teacher. Additionally, school staff stressed the importance of communication about implementation and consistency of expectations across settings and their desire to share discipline data with all staff.

In gathering all suggestions provided, the intervention approach was modified to include additional professional development opportunities for staff and the school leadership team. For instance, feedback informed additional professional development opportunities on universal relationship-building practices, including rationale and steps for welcoming students at the door to establish a sense of belonging, implementing effective classroom routines (e.g., warm-up activity procedures where students know to begin tasks within the first three minutes of class), and wrapping up class in a manner that reinforces connection and prepares students for transition. To proactively prevent and address behavior, professional development opportunities were developed on the topics of understanding behavior as communication, student self-regulation, and designing and implementing break systems in schools. Student feedback also helped develop a training module in which teachers learned about communicating calmly, being discrete, and considering why students engage in certain behaviors. The training also emphasized building student skills and responding appropriately to the severity of the misconduct. Further, materials like reconnection cards and the debrief process were modified to embed language that felt genuine and enhanced student accountability and skill development. The student debrief was also reformatted to communicate empathy, understanding of context, and ideas for what to do next time. Moreover, data-sharing opportunities were incorporated into staff meetings every month, and the ISLA staff regularly checked in with staff about student and teacher reconnections. A roadmap for ongoing professional development was also created with suggestions for data sharing, celebrations of successes, and regular conversations to resolve issues. Lastly, a fidelity tool capturing all active elements of the intervention was developed for teams to self-rate the fidelity of implementation.

The final iteration of the ISLA is a multilayered alternative to exclusionary discipline in which each and every student receives universal supports rooted in classroom prevention and adds additional components for students in need [

42]. The aim of ISLA initially focused on minimizing instructional time lost by coaching students on behavioral skills and engaging educators and students in restorative responses. Nonetheless, ISLA evolved as an approach that further promotes positive student–teacher interactions through helping educators implement school-wide systems, in-class preventative practices, and out-of-class instructional and restorative supports [

42].

During the 2021–2022 school year, all treatment schools’ leadership teams participated in two full-day training sessions (14 h total) covering all elements of ISLA implementation. Though all treatment school leadership teams received the same ISLA training, each school team delivered separate training to their school personnel (e.g., teachers, behavior support paraprofessionals, related service providers) on ISLA elements based on their fidelity of implementation data and discipline needs. Implementation of ISLA on student engagement and school discipline support resulted in meaningful increases in active engagement and decreases in disruptive behavior and school suspensions [

45]. An earlier pilot study also indicated that ISLA was an effective intervention for reducing exclusionary discipline practices and the minutes of instruction students lose when excluded from the classroom [

42]. This study gathered student input on the impact ISLA had on their schooling experience during the intervention year.

1.4. Purpose of the Study

Although studies provide compelling evidence of the detrimental effects of exclusion, there remains limited research on the specific practices that schools can adopt to prevent exclusion and foster positive student–teacher relationships. This study aimed to contribute to the literature by investigating how inclusive classroom strategies, such as those that are part of ISLA, can mitigate exclusionary practices and promote equitable, supportive learning environments. By centering students’ perspectives on school and classroom experiences during ISLA implementation, we wanted to understand how students experienced different components of the ISLA intervention (i.e., prevention at the school level and through classroom practices, teacher responses to behavior, out-of-class ISLA supports, resolutions, and reconnections) to inform further implementation in their local contexts. This study answered the following questions:

What type of school and classroom environments did students experience during the intervention year?

What type of classroom practices supported students’ engagement and in- or out-of-class transitions?

What strategies did students find helpful in repairing student and teacher relationships?

3. Results

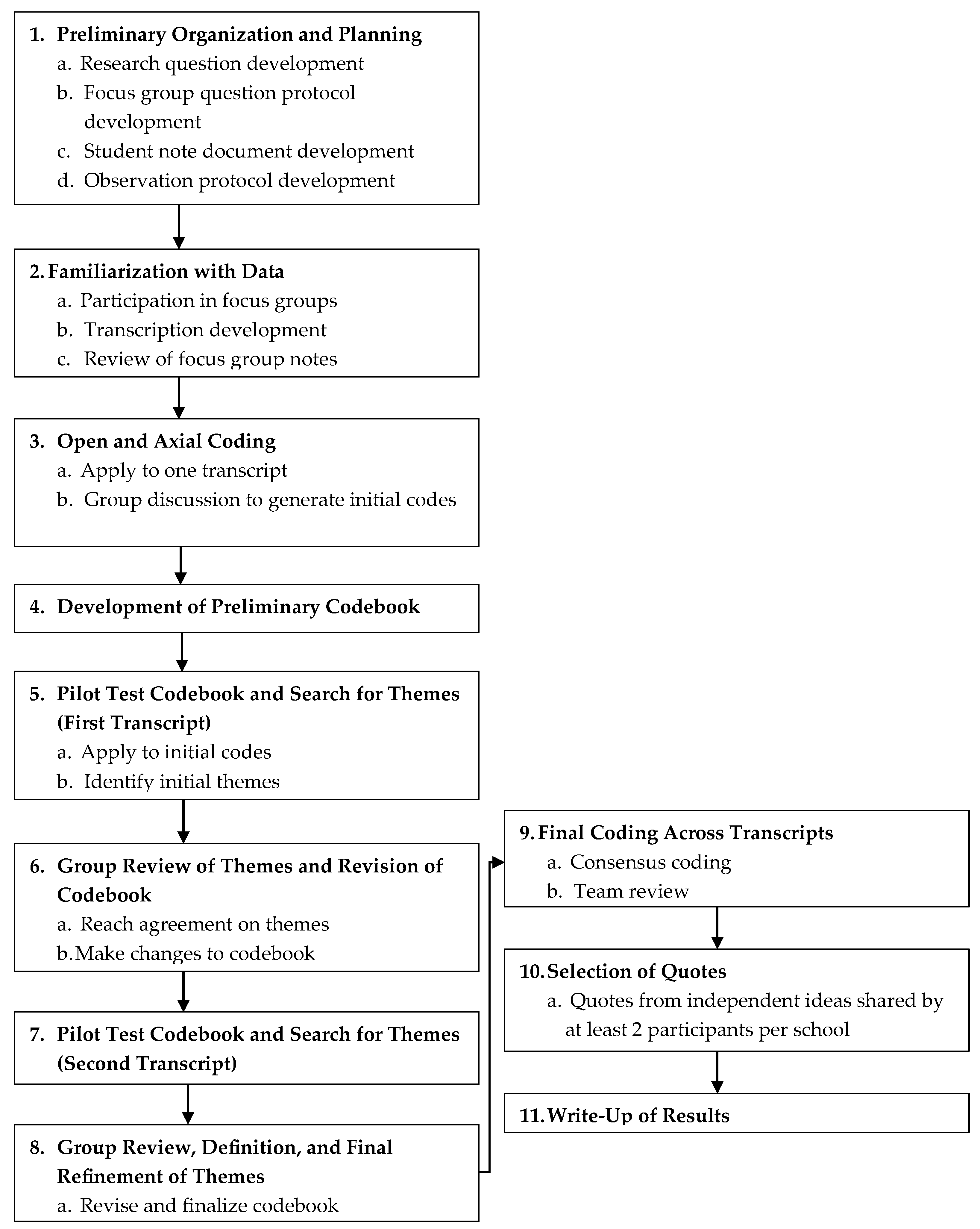

The focus groups took place in the spring of the intervention year for two of the participating schools. The following represents the voices of the students and their experiences at the schools. Up to that point in the school year, each school team had received training on all ISLA components and trained all teachers and staff in various ISLA components. Students engaged with school members throughout the year and may have experienced various ISLA practices up to that point. Students were asked to discuss how their day-to-day interactions with teachers and staff affected them and their peers during the intervention year. The following five themes were identified based on ISLA’s key intervention elements and student experiences: school environment, teacher or staff behaviors, engagement and regulation, in- or out-of-class transitions, and reparations. For more details of subthemes, see

Supplementary Materials. A description of students’ anecdotes about ways ISLA may have impacted their day-to-day experiences is provided below.

3.1. What Type of School and Classroom Environments Did Students Experience During the Intervention Year?

3.1.1. School Environment

Helpful practices. A key goal of ISLA is to promote inclusive learning environments and prevent the overuse of discipline exclusions. Therefore, students were asked to describe characteristics that made (or did not make) the school and staff welcoming to them during that school year. Across focus groups, students described their schools as welcoming places. A particularly positive aspect of their school was the sense of acceptance and support from their community. As a result, many students shared feeling safe and connected to at least one adult at school. One student described feeling “like we have a really good community here. I feel fortunate to be going to such an accepting school”. Another student emphasized how “staff altogether just makes a really welcoming environment to everyone and tries to make people feel safe, so they can talk to the staff if they need to be able to go to the office to get help”. A few other examples of what students said made their school feel safe included the space created for various affinity groups like the “Gay–Straight Alliance” or “Black Student Union”, as well as student-led initiatives promoting “anti-bullying” and “kindness campaigns”.

Hindering practices. Among negative school characteristics, students identified school administrators as not holding teachers accountable when students expressed feeling disrespected by them in sensitive situations. As a student summarized, “The point is it’s like […] if they [teachers] do something wrong, someone talks about it, they kind of get the most minimal punishment […] it feels like they have a level of immunity that it seems the students don’t. Which is kind of really bad when we’ve got […] a specific batch of teachers out of the normal bunch who kind of consistently do things that really needs to be addressed but like no one ever does address it”.

In addition, several students reported not having enough room to pause when overwhelmed by schoolwork or interactions with classmates and teachers. As a student noted, “I just feel like it could be a little bit more normalized to remind kids that they have a place to go talk to teachers who are welcoming, and you’re welcome to take time for yourself if you need to because sometimes it’s hard to ask for that if you don’t know if it’s okay”. Lastly, students from one of the schools identified a lack of positive reinforcements. A student from that school voiced, “I think that there’s kind of a lack of positive reinforcement at school. Sometimes it feels like the only attention you could get from the office is say as a punishment”.

3.1.2. Teacher or Staff Behaviors

Helpful behaviors. Students in both focus groups agreed that most educators in their schools were welcoming, caring, and supportive. One student shared, “I think the individual teachers are very helpful and understanding”. Students described supportive teachers as those who checked in privately with them and created space for them to share any worry or need. As one student said, “He (teacher) noticed that I was slumped in my chair and not in a very good mood. He said I could go for a walk […] I went on a walk and came back. That was really nice, but I still felt kind of down. Then, he wanted to talk to me after class and we talked for a while. It just felt real and genuine”.

Additionally, students identified teachers who use inclusive language as individuals who make the classroom environment positive for them. One student noted, “Most of the staff are really respectful of your pronouns or if you go by a different name”. Another student added, “At the beginning of the year, he [teacher] was very inclusive, and he still is. He said, ‘guys, gals and non-binary pals’ so he was just including everybody in the spectrum for whatever you want to be. It was kind of unexpected because most of the time it’s just like boys and girls, ladies and gentlemen, but he went out of his way to say something different to include everybody”. Providing a sense of safety in the classroom and motivating students through engaging instruction are two other ways teachers positively influence students’ experiences in the classroom. A student concluded, “If you had a teacher that is all accepting and supportive, it’s gonna make you want to go to class more, because if you go to class and you have a teacher that makes you feel safe and secure, you’re gonna want to be there with them, and in turn, you’re going to want to learn after that, if you want to be there”. Students also appreciated and felt connected with teachers who were vulnerable with their students. A student shared, “[Teacher] was like, okay, let me get real off topic here for just a hot second. And he really told us how he was feeling and like he was being honest and he was like I know I am your teacher but also like I have feelings too and my life isn’t always like perfect”.

Hindering behaviors. Despite students’ emphasis on most teachers making school a welcoming place, they singled out a few teachers who made school unsafe for them and their peers. Some ways teachers made students feel unsafe in schools included examples of crossing boundaries, denying special education accommodations, dismissing their concerns, and breaking their trust by sharing confidential information. An example of how a teacher broke boundaries included, “There are some teachers that will make me really uncomfortable. One of the teachers grabbed my hands in front of the entire class and I didn’t say to grab my hands or anything”. In terms of special education accommodations, a student emphasized how “it takes a lot for him [teacher] to even really get close to understanding how these kinds of things [disabilities] can actually affect you. When he thinks of them it seems he thinks of them more as excuses to get out of doing work rather than like actual things that really affect how you do stuff”.

Additionally, singling students out or overtly disrespecting students were identified as hindering behaviors that made students’ schooling a negative experience. For instance, students noted teachers who repeatedly sent out the same students: “I feel like he [teacher] starts to choose certain people that he sends out […] and he [teacher] will send those people consistently”. Although, spoken as the exception, students commented on ways some teachers humiliate students for asking questions, not understanding content, or presenting themselves in a certain light. A student expanded, “One teacher in particular who openly calls out kids and humiliates them in front of class, makes them feel slow, like says pretty degrading stuff to kids about their intelligence”. As part of feelings that come up when feeling disrespected, a student described “that for a lot of students might have a like panic attack in that class because it can get really scary with the yelling, getting up in your face, and pointing you out on the spot”. Additionally, some students felt disrespected for their identity. For instance, a student described “One of the things that they said that really got to me and stuck with me is I was walking through the hallways one time, and I had my makeup done and stuff. They came up to me and they were like, ‘Oh, so you’re like a little black emo girl now,’ and it really got to me”.

3.2. What Type of Classroom Practices Supported Students’ Engagement and In- or Out-of-Class Transitions?

3.2.1. Engagement and Regulation

Classroom-wide supports. In reflecting upon supports in the classroom that positively influenced their ability to stay in class and learn, students emphasized the positive impact breaks had on calming them down and discussed inconsistencies across teachers in allowing the use of this strategy. When students spoke of those who allowed students to take breaks, students emphasized calming down as a result of the opportunity. One student shared, “If you’re anxious or stressed out and you need a break, if they do let you go outside. If you don’t just want to be in the hallways, the office […] got some rooms in the back to let you sit there and do whatever you need to do to calm yourself down”. Based on student discussion, teachers who encouraged the use of breaks and those who didn’t were “pretty split”. Other opportunities teachers provided to students to support their learning experience in the classroom consisted in providing them with tools that helped with grounding. The most common opportunities included access to “fidgets” and “playing music” while completing work. Other class-wide supports mentioned were “preferred seating”, “providing additional work time”, and scaffolding priorities by listing them on the whiteboard.

Individual strategies. The students also discussed strategies they used to cope with moments in their school day that affect their ability to learn. In the absence of class-wide systems, students relied on self-selected breaks such as “drawing or doodling”, “going to the bathroom”, “humming”, “taking deep breaths”, “listening to music”, talking to themselves, or “switching tasks”.

3.2.2. In- or Out-of-Class Transitions

Wishful practices. As part of ISLA, teachers can send students to an ISLA-trained staff member for additional support when students need additional assistance developing a missing skill or becoming more aware of their behavior within the classroom. Focus group participants were asked to describe what things they found helpful when leaving or returning to classrooms. Students discussed two helpful practices they wished were in place: (a) seamless transitions and (b) teaching empathy. During discussions regarding transitions, students discussed their comfort level when coming and going went unnoticed by their peers versus when everyone in the room judged them during leaving or returning. A student shared, “I think if somehow we could enter back in without everyone looking at you and wondering where you’ve been. That would be amazing”. Further, students discussed the judgment they felt from peers and a way to prevent it. A student expanded, “I think what you can prevent is not the wondering but the judgment for it. But that’s also really hard to prevent. I think the best way to prevent that type of judgment is to teach people to have empathy, like, more empathy than they do. Everyone has probably been sent out in the classroom at one point and if you can remember that and call on that empathy somehow, then you can suppress that judgment”.

Hindering practices. In ISLA-implementing schools, students identified many aspects of transitions that hindered their experience, regardless of the fact that respectful corrections were discussed with teachers during ISLA training. Students most emphasized the anticipation and discomfort they felt when coming back to the learning environment after being sent out of the classroom or returning after an extraordinary event. After being sent out of class, students would rather not return. One shared, “Depending on what it is, obviously, but I think if you’re sent out of the class, I think that’s embarrassing as it is, you don’t want to come back because you’re sent out of the class”. Students also spoke of the ineffectiveness of being sent out of the learning environment. A student said, “If you’re being disruptive in class, and one of the teachers sends you out, then you don’t want to come back because it’s not something that you enjoy what was happening in the class. Like, you wouldn’t really disrupt something that is fun for you, I guess. So getting sent out just makes you feel like, you know, it’s weight off your back. You don’t have to go back. You don’t want to do that”. Besides the identified issues, students also expressed confusion about expectations, either because they did not receive input regarding what they did wrong, did not know how long they needed to remain outside, or because they did not have access to information missed while out. Lastly, students from one school were also hesitant about being escorted back to the room by another educator. A student summarized, “I feel like someone walking you in would be, like, even more judgmental”.

3.3. What Strategies Did Students Find Helpful in Repairing Student and Teacher Relationships?

Reparations. An active component of ISLA is supporting students and teachers in repairing their relationship after a classroom incident leading to the need for support from an ISLA-trained staff. In asking participants about experiencing strategies that promoted reparations of relationships between teachers and students, the group mostly identified practices that hindered efforts, although some helpful strategies were mentioned.

Helpful practices. Positive experiences were described as having teachers aiming to understand their viewpoint and providing the opportunity to explain themselves. A student emphasized, “When you have empathy for someone else, when you can understand what they are feeling and what they are going through, you can start to feel kindness towards them and try to repair that bond […]. You can’t get anywhere if you’re both just like, ‘I’m right.’ You know, like, it doesn’t work that way”. At points when students spoke of wanting to get a point across to an unreceptive or intimidating teacher, students identified having a mediator as a helpful strategy that supports reparations.

Hindering practices. On the other hand, students experienced teachers who treated students “like super-young children”, tried to “intimidate” them, or “did not offer a solution” after an incident between them. Students mentioned being more receptive toward teachers who wanted to understand the underlying reason behind their actions instead of immediately pointing out what they did wrong. A student said, “I think it’s best if, like, I’m sent outside and then they talked to in a way that is like, ‘Why did you do that?’ or like ‘What got you to that point?’ […] instead of, ‘What you did is wrong, and this is what you should do now to make up for it.’ Even if that’s true, even if you should make up for it and you did do something wrong”. Current conversations with teachers were described as “teacher versus student” or perceived as “student’s personally attacking the teacher”, which may more likely lead students to not admit being in the wrong.

4. Discussion

Feedback from school partners, inclusive of students, informed the refinement of ISLA components. After informing changes to the intervention, we asked students to describe their experience in schools during the intervention year to better understand how various elements of ISLA influenced their interactions with educators. Feedback from students emphasized a welcoming school environment, with the majority of educators in the school being supportive, warm, and caring. Further, fidelity data on the classroom-level implementation of the ISLA relationship-building strategies demonstrated that teachers across both schools implemented these elements with high fidelity, which had a significant impact on increasing student engagement and decreasing disruptive behaviors [

45]. Numerous studies have shown that schools that are welcoming to students and where teachers can establish and maintain positive relationships with their students have the greatest impact on students’ academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health outcomes [

32,

51,

52,

53]. It was evident from our conversations with students how important it is for teachers to check in with them when they appear frustrated or struggling with schoolwork or personal issues. The act of showing care and empathy was the underlying theme of many examples of teachers building safe learning environments in which students could express their needs. Rather than creating a predictable routine at the end of class for community building and learning as per ISLA training, these students’ experiences indicate that teachers are taking a more individualized approach to foster community building and social–emotional learning. This finding aligns with past research showing that wrapping up class with intention is the class-wide preventative component with the least implementation fidelity [

45].

Further, the use of inclusive language by teachers in these schools was consistently identified by students as an important component of a positive learning experience. Teachers who used inclusive language and navigated sensitive conversations about identity were seen as accepting, inclusive, and respectful of diverse students. These findings are consistent with research investigating LGBTQIA+ individuals’ use of language to build agency and create a place that feels welcoming, empowering, and nourishing of connections [

54]. Moreover, practices like the use of inclusive and affirming language as described by students are of great importance, as these are linked to positive teacher–student relationships, student mental health and well-being, self-esteem, and academic outcomes [

55,

56]. Further, teacher integration of affirming practices in schools is known to predict LGBTQIA+ students’ connections with their learning environment, well-being, positive personal transitions, and educational and social success [

57,

58]. The use of inclusive language fosters a sense of belonging for LGBTQIA+ students, ensuring their identities are respected and affirmed within the classroom environment. This connection to belonging highlights how deliberate linguistic choices can reduce feelings of isolation and promote emotional safety. In addition, such practices strengthen student–teacher relationships by fostering trust and mutual respect, as students perceive educators who use inclusive language as empathetic and supportive allies. These interactions contribute to creating equitable and supportive learning spaces, which are crucial for marginalized student populations.

Although the exception, the negative interactions students expressed having with a few teachers are of concern. Harmful, insensitive, and embarrassing interactions with teachers are known to have adverse effects on individual students and the classroom community [

59]. As a result, students are often distracted from schoolwork and thus learning is diminished instead of enhanced [

60,

61]. Further, research has shown that aggression toward students’ identities harms them psychologically [

62,

63]. Students in this study verbalized such an impact. There may be a need for a multilayered support system for training and coaching teachers in preventative relationship building and school belongingness based on these findings, where administrators and school leaders create a system in which identified teachers receive direct support, and potentially harmful practices, language, and interactions are addressed early.

Student feedback also reinforced the need for additional school training in creating break systems and understanding their influence on student engagement and self-regulation in the classroom. Students noted that whether part of a systematic classroom approach or not, pausing was important for them when overwhelmed by schoolwork or personal issues, and that individual strategies were used to manage their stress and learning. There is a need and opportunity for educators to encourage building self-regulatory skills by creating an approach to break systems in their classrooms. The creation of such systems may prevent fatigue among students and enable them to reflect on how to make sense of ongoing events in their lives, and this is why it is a component of the class-wide preventative practices in the ISLA model [

64].

Lastly, the degree of discomfort middle schoolers may feel when perceiving judgment from their peers was a significant theme students voiced when reflecting on transitions to or from class and repairing relationships with teachers. Students prefer for reconnection conversations to happen privately or in a way that does not bring additional attention to them, which is consistent with the ISLA training model on making amends. Additionally, students raised the point of centering empathy in the classroom and having teachers embed more learning opportunities in class to establish empathy as a value that everyone applies to understand and support students experiencing difficult interactions with teachers and navigating the transition back to the classroom. In view of this, universal classroom lessons focusing on empathy and kindness deserve further consideration to strengthen a welcoming classroom environment through ISLA. Further, students’ descriptions of teacher interactions hindering their return to the classroom support the need for additional teacher training in empathic listening, perspective-taking, and using reframing statements to enhance a positive and productive return to the classroom and relationship repair.

4.1. Implications for Practice

The testimony of students gives insight into how ISLA supported educators and students during the intervention year, particularly by building relationships, bringing mental health awareness to the forefront, creating a safe and caring learning environment, and respectfully addressing behavior. In order to create a more welcoming school environment, school staff can use student feedback on the ISLA process to focus on professional development opportunities for staff and evaluate current school systems based on what students need. Specifically, feedback from students can guide the development of training modules that emphasize restorative practices and strategies for reducing discipline exclusion, fostering empathetic classroom interactions and alternatives to punitive measures. Schools can also use feedback to evaluate the effectiveness of ISLA practices in improving inclusivity and identity areas where adjustments are needed to better meet students’ social, emotional, and behavioral needs.

Students reported feeling most welcome and safe in schools that prioritized connecting with students, assessing and caring about their needs, and building spaces for self-regulation to occur, as well as spaces to connect about personal issues and identities. Embedding routines in class that allow for connections and social–emotional wellness, as well as establishing clear expectations about how to take care of yourself and engage in self-regulatory activities, are ways educators can directly support student autonomy and ability to cope with stressful demands during the school day. For example, educators can establish “calm corner” protocols where students know they can access a quiet space to regroup when overwhelmed, with clear instructions on how to use the space effectively—such as engaging in deep breathing or using provided sensory tools. Moreover, setting explicit expectations for transitions, like using a checklist of steps to wrap up assignments, ensures students understand how to stay organized and manage their time, fostering self-regulation skills that are crucial for their overall well-being. Additionally, students noted that teachers can support their transitions in and out of the classroom by teaching everyone to be more empathetic when students may feel embarrassed and self-conscious after a difficult interaction or during their return to class. Schools can leverage student feedback to critically evaluate discipline policies and practices, replacing exclusionary approaches with restorative alternatives. For example, adopting student-recommended strategies, such as creating spaces for self-regulation and prioritizing empathy in teacher interactions, can reduce classroom removals while addressing underlying issues contributing to behavioral challenges. Feedback-driven interventions empower schools to respond to students’ needs while fostering a positive and inclusive learning environment.

Student feedback on teacher accountability speaks to the need for schools to establish clear policies for administrators on handling repeated negative interactions between students and educators. Student feedback can inform revisions to policies on disciplinary exclusion to ensure that punitive measures are minimized and restorative alternatives are prioritized. By fostering accountability for both students and staff, schools can create systems that reduce exclusionary discipline and build trust and mutual respect. For example, schools can introduce structured restorative practices, such as facilitated dialogues where students and teachers collaborate to resolve conflicts and rebuild relationships. Training educators in restorative techniques, including active listening and collaborative problem-solving, can empower both students and staff to address conflicts constructively and equitably. Incorporating student input into policymaking processes will allow schools to address power imbalances and establish clear guidelines for resolving negative interactions between staff and students in a way that encourages equitable treatment. Schools can also implement anonymous reporting systems that provide students with a safe way to share concerns about harmful teacher behavior, ensuring that administrators enforce policies consistently and equitably. Students noted the imbalance between staff and students whereby students were punished in a manner that disengaged them from class and teachers were perceived to have immunity despite their harmful behaviors towards students. Students also stated that developing a balanced relationship between students and staff fostered strong relationships and increased the number of trusted adults present in the school buildings. Addressing this imbalance requires creating transparent accountability systems for teacher conduct coupled with restorative processes that enable meaningful dialogue and repair between students and teachers, ultimately fostering a culture of mutual respect. School leaders should assess if current policies and practices address harmful teaching behavior and support restoration in a way that facilitates learning and motivation for students and staff alike.

Student feedback also spoke to the importance of language and thoughtfulness on the part of teachers. Simple interactions that occur throughout the day, such as a teacher checking in or acknowledging students in the hallway by name, made a meaningful difference in students’ feelings of belonging. Additionally, inclusive language being adopted by teachers aided students in feeling like they belonged, regardless of their background. Using student feedback, schools can emphasize inclusive language and culturally responsive teaching practices in ISLA implementation to further reduce disciplinary exclusion. For example, embedding routines that recognize and value diverse student identities can help create a sense of belonging and reduce behaviors arising from disengagement or frustration. Professional development informed by student feedback could focus on improving teacher–student communication and promoting proactive approaches to managing classroom challenges, reducing the likelihood of disciplinary actions.

In the face of challenging behaviors, teachers’ ability to engage empathetically and seek to understand a student’s rationale can help students feel at ease in the classroom. The anecdotes shared by students suggest that many are self-conscious about being singled out in front of their peers, thus encouraging discrete redirections from educators and opportunities to understand student behavior as a form of communication can benefit students and staff in building a classroom environment that is supportive of students and fosters motivation for learning.

Ultimately, integrating student feedback into school-wide initiatives provides a pathway for improving ISLA implementation and reducing disciplinary exclusion. By ensuring that students’ voices guide professional development, policy refinement, and classroom practices, schools can create environments that are supportive, equitable, and conducive to learning for all.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations are present in this study. As a first limitation, focus groups were not conducted with the other intervention and control schools involved in the larger quasi-experimental study [

45], limiting the size of the sample and the generalizability of the findings. Not having information from all schools limits a broader understanding of how students experienced ISLA across different settings, including comparisons to the experience of students in schools not implementing ISLA. Findings are specific to the experience of students in schools included in the study and cannot account for variability across different school contexts. Logistical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic presented significant logistical challenges that directly impacted the study methodology and data collection. Disruptions caused by teacher and staff shortages, competing responsibilities among school personnel, and the implementation of added health and safety protocols limited the researchers’ ability to schedule focus groups and recruit a larger pool of participants. These constraints reduced the diversity of student perspectives that could be represented in the findings and potentially introduced bias by prioritizing convenience in participant selection. Furthermore, the heightened stress and operational difficulties within schools during the pandemic may have influenced students’ responses, particularly their perceptions of connectedness and support. As such, the findings must be interpreted with caution, given these external factors that may have affected the quality and depth of the collected data. Furthermore, because the research questions and results were specific to the ISLA intervention, the findings may not extend or apply to other interventions or educational contexts. However, we learned about broader supports that classroom teachers provide, which students reported as helpful for their learning and connectedness. Although their reports suggest potential promising practices in middle schools, additional evidence is needed to substantiate these observations.

Future research can address limitations by engaging in broader data collection across a more diverse range of schools, including both intervention and control settings. Expanding the sample size to include schools from varying locations, socioeconomic contexts, and demographic compositions would enhance the generalizability of findings. This could be achieved by supplementing focus groups with student surveys or school climate reports and longitudinal tracking of student outcomes. Engaging students who have not experienced ISLA implementation could provide contrasting perspectives, offering deeper insights into the role of specific intervention in fostering student connectedness and learning. Although focus group participants were evenly distributed between “low risk” or “at risk” of experiencing exclusion, among proportionate school sociodemographic characteristics, their viewpoints may not reflect those expressed by other students in their schools. Future mixed-method research that examines both qualitative and quantitative reports of school climate and inclusive practices is needed to better expand on the findings and understand what aspects of school and classroom functioning have the greatest impact on students’ sense of belonging. For instance, statistical analyses could identify patterns in students’ perceptions of inclusivity, with thematic analysis uncovering underlying factors that shape these perceptions. Further, disaggregating these data by race, gender, and other student characteristics will allow us to better understand which groups of students feel most supported by existing school-wide systems and practices and which groups do not. Such analyses are critical for informing equitable interventions and addressing disparities in student experiences.