Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, young people have become overexposed to social media and online gaming, making them more vulnerable to online violence such as cyberbullying. The aim of this study was to determine whether social media and online gaming pose a risk for cyberbullying through time spent online and whether there is a sex that is more vulnerable to this phenomenon. The survey included a sample of 4338 students (52.4% girls; age range, 11–19 years, M 14.1 SD 1.6) attending lower and upper secondary schools. Multiple moderated mediation regression models by sex were conducted, showing a relationship between social media and online gaming, time spent online outside of school, and cyberbullying. The results show that young girls are at higher risk of cyberbullying via social media, and boys are at higher risk of cybervictimization through online gaming. The findings may encourage other researchers to study the phenomenon, taking into account the role of parents and other educators.

1. Introduction

With social media, bullying has conquered the Internet and takes the form of cyberbullying, which is perpetrated electronically via electronic devices [1,2] and has the following characteristics: Repetition over time, a desire to victimize a person, and an imbalance of power [3,4].

Cyberbullying is enabled by the ability to use digital and social skills, in particular, the ability to use “information and communication technologies” (ICT) [5,6]. Relationships on social media are mediated through a screen, and the dynamics that lead to becoming a cyberbully are different from those of traditional bullying [7,8].

Cyberbullying can be carried out in different ways: not only via social media but also via chat in online games that could be competitive, and this represents a risk for cyberbullying [7,9,10,11]. This competition can lead to aggression being taken out on other players, and using a fake profile can give the impression that the player does not have to take responsibility for their actions [7].

1.1. Sex Differences in the Use of Social Media and Online Gaming

Several studies [12,13,14] have shown that girls spend more time on social media than boys. Girls use the Internet more to communicate with friends but also emphasize that girls use problematic social media to a greater extent [15,16,17]. In addition, the prevalence of intensive Internet use was found to be higher in girls than boys because girls take much more care in their appearance than boys and seek feedback on their personal value [17,18].

To explain the massive use of online games, studies have considered communication and interaction with other players (e.g., ref. [19]). Several online games require cooperation between players (massively multiplayer online games; MMOG; online role-playing games; MMORPGs), such as World of Warcraft, which poses a risk for cyberbullying [20].

1.2. Sex Differences in Cyberbullying

The findings on the role of sex in cyberbullying are unclear. Some studies show that boys are more involved in cyberbullying than girls [21,22]. In this context, research on cyberbullying has emphasized sex-specific characteristics: The HBSC [23] found that boys are more likely to be perpetrators of cyberbullying, while girls are more likely to be victims of cyberbullying, which is also confirmed by the comparative EU report Kids Online [24]. Girls’ use of social media makes them more vulnerable to relational aggression, and they may be more likely to be involved in cybervictimization than boys [18,25]. Other research shows that boys and girls are equally involved in cyberbullying [26,27].

1.3. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cyberbullying: More Time Spent Online as a Risk Factor

The COVID-19 pandemic was a source of insecurity and stress.

In many countries, including Italy from February 2020 because of lockdown, children and adolescents spent much time online during the COVID-19 pandemic for remote school lessons [24], with overexposure to social media and the Internet [28,29,30,31].

A survey by Connected Generations (https://terredeshommes.it/comunicati/bullismo-cyberbullismo-parlano-ragazzi-dati-dellosservatorio-indifesa/, accessed on date: 2 May 2024) presented on 9 February 2021 on the occasion of Safer Internet Day, showed that: 1 in 5 respondents described themselves as almost always connected, with 6 in 10 being online 5 to 10 h a day. For 59% of students, incidents of cyberbullying have increased; 61% of respondents said they had been bullied or harassed, and 68% reported witnessing cyberbullying. Girls felt less safe on social media and feared revenge porn in particular.

In their survey, which included a sample of more than 5000 students, Zanetti and colleagues [32] found that 25.5% spent 2 to 3 h a day online and 19.09% spent more than 5 h. For those who spend so much time online, this could pose a problem, as their Internet use could become a risk, involving a superficial and unformed approach [33]. In terms of online activities, Zanetti and colleagues [32] have shown that in their study population aged 11–19 years, social media was used by the majority (85.57%), and almost 50% used online games (Fortnite, Minecraft, etc.). The 2021 edition of the survey on the lifestyle habits of young people in Italy, conducted by the “Adolescenza e Istituto di ricera IARD1” laboratory (https://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/tecnologia/internet_social/2021/06/22/social-e-adolescenti-nella-pandemia-boom-di-utilizzo_4a6d9c7f-43c4-4644-a716-202c95d27f1e.html, accessed on date: 2 May 2024) on a sample of more than 10,500 students aged 13–19, shows that 80% of young people said they used social media more in the year of the pandemic than in the past, and 45% of them said they used social media much more than in the past.

1.4. Current Study

As reported above, the dynamics of cyberbullying differ among boys and girls in terms of their different use of the Internet. Girls spend more time on social media and boys on online games. It can, therefore, be assumed that girls are more involved in cyberbullying on social media than boys. Our aim was to contribute to the literature by investigating whether there were sex differences in cybervictimization and cyberbullying on social media and online games during the COVID-19 pandemic, taking into account the increased time students spent online during the lockdown. In Italy, especially in Lombardy, with the first COVID-19 patient from Wuhan, the situation was particularly serious as it was the first European state to be confronted with the pandemic. Lombardy took the strictest quarantine measures outside of China [34].

This research study is part of a larger project that aimed to investigate the quality and use of electronic devices by adolescents, the quality of relationships with their parents, family members, educators, and peers, the use of online platforms for e-learning and the relationship between cyberbullying and e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Using multiple regression modeling, we examined the role of sex as a moderator to understand the differences between boys and girls in how they commit and suffer from cyberbullying. We also examined the role of greater time spent online as a mediator to understand whether there was an increase in the phenomenon of cyberbullying, given the difference in boys’ and girls’ use of the Internet.

We examined these specific research questions:

H1: Are social media and online gaming associated with online risks in the form of cyberbullying and cybervictimization during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Both online gaming and social media have a higher risk of being involved in cyberbullying [19,20].

H2: Boys were more likely to be affected by cyberbullying and cybervictimization through online gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic, while girls were more likely to be affected by social media.

While online gaming is a favored online activity of boys, research shows that adolescent girls are significantly more likely to use social media than their male peers [35,36].

H3: Time spent online mediates the relationship between social media and online gaming and exposure to cyberbullying during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Boys spend more time than girls playing online games, and girls spend more time than boys on social media: this would make girls vulnerable to violence, such as cyberbullying on the respective virtual platforms they use to interact with others [37,38].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study sample was 4338 students (2272 girls, 52.4%; 2066 boys; age range, 11–19 years [M 14.1; SD 1.6]) attending lower secondary (n = 9, 5 of which were located in the city of Pavia and 4 in the province of Pavia) and upper secondary (n = 11, 5 of which were located in the city of Pavia and 6 in the province of Pavia) schools (total n = 20).

The sample size was estimated using G*Power (40). Considering the F test and multiple linear regression with four predictors, an expected power of 0.80, an effect size of 0.02, and an alpha level of 0.05. The optimal sample size should be 550, so the sample was adequate for the present study. Of the 95% of students whose consent we had obtained, 85% of them actually completed the questionnaire.

In total, 5% of participants were excluded from the analysis because they did not answer the questions of interest (i.e., the items on cyberbullying during the pandemic, hours spent online outside of school, use of online games, and social media). There was no missing data in the study sample, and Mahalanobis distance was performed for the entire sample to confirm that no participants were outliers, so they were included in the analyses.

2.2. Measures

To this end, a self-report questionnaire was developed to address a unique situation in which schoolchildren found themselves locked in their homes, unable to communicate with peers and relatives via social media, and suffering from unprecedented social media overload.

The first section of the questionnaire contained items to collect demographic data, including sex (boys = 1, girls = 2). Four items assessed risky online behavior (before and during the pandemic), one item assessed time spent online without distance learning, one item assessed parental control, and one item assessed online activities. The second session included items assessing the dimensions of online experiences. We report on the content below. For this study, we included two items assessing cybervictimization and cyberbullying during the pandemic.

- Cybervictimization during the pandemic. The following question was used to assess the experience of cybervictimization during the pandemic: Indicate whether you experienced something similar during the COVID-19 pandemic in your social relationships with your friends and/or classmates. Participants could answer multiple options that were: I felt that social relationships alone replaced the need for face-to-face contact with classmates, friends, and family (video calls, chats, etc.) = 1; I used social to tease someone because it could not be done in person = 2; I have noticed that classmates or people I know have been teased the most = 3; I have been teased the most = 4; I have organized social jokes towards a classmate, friend, or acquaintance = 5; The exclusive use of social media to relate to others has made it difficult to resume normal relationships in person, after lockdown, creating a minimum of embarrassment to relate again not behind a screen = 6; None of the previous options = 7. For the analysis, the response of interest—I have been teased the most—was isolated and assigned a score of 0 for those who had not had that particular experience and a score of 1 for those who had. In this way, the variable was converted into a dichotomous variable.

- Cyberbullying perpetration during the pandemic. The following question was used to assess the experience of cyberbullying during the pandemic: Indicate whether you experienced anything similar during the COVID-19 pandemic in your social relationships with your friends and/or classmates. Participants could answer multiple options that were: I felt that social relationships alone replaced the need for face-to-face contact with classmates, friends, and family (video calls, chats, etc.) = 1; Social media was used to tease someone because it could not be done in person = 2; I have noticed that I have been teased the most = 3; I have organized social teasing toward a classmate, friend, or acquaintance = 4; The exclusive use of social media to relate to others made it difficult to resume normal in-person relationships after lockdown, creating a modicum of awkwardness to relate again not behind a screen = 5; None of the above options = 6. For the analyses, the response of interest—I have organized social teasing toward a classmate, friend, or acquaintance—was isolated and assigned a score of 0 for those who had not had that particular experience and a score of 1 for those who had. In this way, the variable was converted into a dichotomous variable.

- Time spent online. One item assessed the time, in terms of the number of hours, spent online, excluding the time spent in distance school learning (“How many hours a day do you spend online on average (excluding remote school learning)?”). The item was scored on a 6-point Likert scale as follows: 1 = 1 h; 2 = 2 h; 3 = 3 h; 4 = 4 h; 5 = 5 h; 6 = more than 5 h.

- Online activities. Participants answered, with multiple options, to the following question: “What activities do you carry out online?”. The options were: social media (TikTok, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc.) = 1; online games (Fortnite, Minecraft, Roblox, FIFA, etc.) = 2; Graphics (photo editing; video editing; etc.) = 3; streaming TV or other videos to watch (YouTube; etc.) = 4; live online courses (e.g., music courses) = 5. For the analysis, the responses of interest—social media (TikTok, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc.) and online games (Fortnite, Minecraft, Roblox, FIFA, etc.)—were isolated and assigned a score of 0 for those who did not use both social media and online games and a score of 1 for those who both used social media and online games. In this way, the variables were converted into dichotomous variables.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were recruited by asking principals and teachers in their schools to participate during the March–April 2021 lockdown (the first Italian national lockdown). The researchers informed principals about the survey and the logistical details of the study in a remote meeting. Students were recruited from the schools that had accepted the invitation to participate. Participating schools sent a letter to students’ families describing the research project and obtaining parental consent. Parents/guardians who agreed to their child’s participation returned an electronic, signed consent form to the schools, which they forwarded to the researchers. The questionnaire was administered in a digitalized form via SurveyMonkey, an online platform that guarantees the anonymity of respondents. The platform was opened at an agreed time so that teachers could help administer the questionnaire and administration took an average of 45 min per classroom. Students completed the questionnaire during school hours, and data collection lasted 20 days.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the APA and the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Pavia (No. 097/22).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

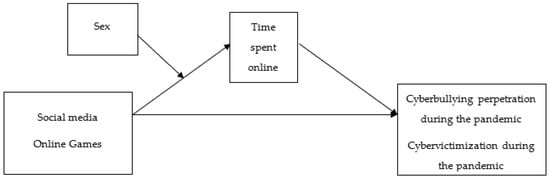

We performed means, standard deviations, bivariate correlations, and a set of t-tests to compare boys and girls with other scores using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 28.0). According to empirical guidelines [39], correlations around 0.15 are considered small, around 0.25 medium, and around or over 0.35 large. For sex differences, with the p-value adjusted according to the number of hypotheses (Bonferroni correction), Cohen’s D was used to determine the effect size for the significant differences among boys and girls and the following guidelines were used: small effect size (d < 0.20); medium effect size (d > 0.50); large effect size (d > 0.80); very large effect size (d > 1.30) [40] PROCESS (Version 4.1; Model 7 [41]) was used to test four multiple moderated mediation logistic regression models. Specifically, Model 1 tested the associations between Internet use for social media as the independent variable and cyberbullying during the pandemic as the dependent variable. Time spent online was the mediator, and sex was the moderator. Model 2 tested the associations between using the Internet for social media as the independent variable and cybervictimization during the pandemic as the dependent variable. Time spent online was the mediator, and sex was the moderator. Model 3 tested the associations between Internet use for online gaming as the independent variable and cyberbullying during the pandemic as the dependent variable. Time spent online was the mediator, and sex was the moderator. Model 4 tested the associations between Internet use for online gaming as the independent variable and cybervictimization during the pandemic as the dependent variable. Time spent online was the mediator, and sex was the moderator. Since the dependent variables were dichotomous, all the Beta results of the regression model were expressed in a log-odds metric [41]. The conceptual models are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual models.

Bootstrap estimations were considered to test the significance of the indirect effects for different groups indicated by the moderator (boys/girls) with 5000 samples [41]. A bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed by determining the effects at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles; a significant indirect effect was present when 0 was not included in the CI.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of the investigated variables are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, a small and positive correlation emerged between time spent online and social media and online games. There were also small, positive, and significant correlations between time spent online and both cyberbullying and cybervictimization. As far as Internet use is concerned, there was a medium-sized, negative correlation between the use of social networks and online games. Different results were found for the correlations between the use of the Internet (social network/online games) and the form of cyberbullying/cybervictimization. Specifically, the use of social networks showed a small and positive correlation only with cyberbullying, while the use of online games showed a small and positive correlation only with cybervictimization. Cyberbullying and cybervictimization were positively correlated, even if the correlation was small. Regarding the relationship between sex (boys = 0) and the other scores, there was a large, positive correlation with social media and a small, positive correlation with time spent online. Instead, a large, negative correlation occurred between online gaming and a small, negative correlation with cybervictimization. In contrast, there was a non-significant correlation between sex and cyberbullying.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations.

The results of a set of t-tests comparing the scores of boys and girls are shown in Table 2. Except for cybervictimization, there were significant differences between boys and girls for the other scores. Specifically, girls used social media more than boys, with a small effect size, while boys used online games more than girls, with a very large effect size. In addition, girls spent more time online than boys, while boys reported higher average scores for cyberbullying compared to girls, even if both differences were small in effect size.

Table 2.

t-tests for sex.

3.1.1. Model 1: Cyberbullying Perpetration during the COVID-19 Pandemic through the Use of Social Media

Results of the moderated mediation Model 1 are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Model 1 results.

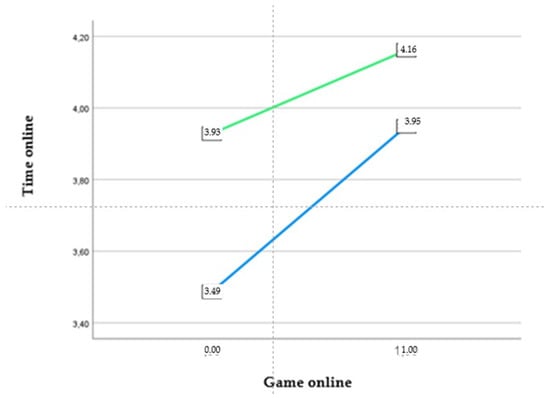

The use of social media was not statistically significantly associated with time spent online, while sex (boys = 0) showed a negative and significant association with time spent online, meaning that girls tended to spend more time on social media than boys. The interaction effect of sex and the use of social networks was positively and significantly associated with time spent online. As illustrated in Figure 2, simple slope analysis showed that sex moderated the relationship between the use of social media and time spent online, with girls using social media more than boys.

Figure 2.

Simple slope for Model 1 and Model 2. Blue line = Boys; Green line = Girls.

Concerning the relationships on the dependent variable of cyberbullying, both social media and time spent online showed positive and significant associations. The conditional indirect effects of social media usage on cyberbullying via time spent online for sex showed for boys a lower effect compared to girls. In addition, the positive and significant moderated mediation index confirmed that sex moderated the indirect effect.

3.1.2. Model 2: Cybervictimization during the COVID-19 Pandemic through the Use of Social Media

Results of the moderated mediation Model 2 are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model 2 results.

As for Model 1 presented above, the use of social media was not statistically significant with time spent online, while sex (boys = 0) showed a negative and significant association with time spent online. The interaction effect of sex and the use of social networks still presented a positive and significant association with time spent online. Again, simple slope analysis showed the same results as Model 1 (see Figure 2), with girls using social media more than boys.

Results on cybervictimization showed a not statistically significant association with the use of social media, while there was a positive association with time spent online. As in Model 1, the conditional indirect effects of social media usage on cybervictimization via time spent online for sex showed a lower effect for boys compared to girls. The moderated mediation index confirmed that sex moderated the indirect effect.

3.1.3. Model 3: Cyberbullying Perpetration during the COVID-19 Pandemic through Games Online

Results of the moderated mediation Model 3 are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Model 3 results.

As for Model 3 presented above, both positive and significant associations emerged between time spent online and sex (boys = 0) and the use of the Internet for games online. Also, a similar interaction effect emerged on time spent online. As illustrated in Figure 3, simple slope analysis showed that boys used more games online than girls.

Figure 3.

Simple slope for Model 3 and Model 4. Blue line = Boys; Green line = Girls.

Regarding the results on the dependent variable (cyberbullying), no significant association emerged with the use of games online, while a positive association was observed with time spent online. The conditional indirect effects of the use of games online on cyberbullying via time spent online for sex showed a higher effect for boys compared to girls. The moderated mediation index confirmed that sex moderated the indirect effect.

3.1.4. Model 4: Cybervictimization during the COVID-19 Pandemic through Games Online

Results of the moderated mediation Model 3 are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Model 4 results.

The use of the Internet for games online showed a positive and significant association both with time spent online and sex (boys = 0). The interaction effect of sex and the use of games online showed a negative and significant association with time spent online. Again, simple slope analysis showed the same results as Model 3 with boys, who used more games online than girls.

The results on cybervictimization showed significant associations between the use of games online and time spent online. The conditional indirect effects of the use of games online on cybervictimization via time spent online for sex showed a higher effect for boys compared to girls. The moderated mediation index confirmed that sex moderated the indirect effect.

4. Discussion

Many studies focus on the combination of social media and online gaming in relation to cyberbullying precisely because both allow millions of people to be connected at the same time, making them more vulnerable to violence, including cyberbullying [25,42,43].

Regarding H1 (“Are social media and online gaming associated with online risks in the form of cyberbullying and cybervictimization during the COVID pandemic?”), we confirmed that online gaming was particularly associated with cybervictimization and social media with cyberbullying.

Regarding online gaming, a positive association with cybervictimization was found. This could be explained by the fact that online gaming normalizes aggression towards other users and one’s fellow players, as will be explained later; as a result, users do not see their behavior as dangerous and aggressive and do not classify it as cyberbullying [44,45].

As sociability and teamwork are prevalent in online multiplayer games, so are hostility and harassment, known as online aggression or cyberaggression [46]. Regarding online gaming, users normalize aggression toward other players, not only toward opponents but also toward their teammates when they do not perform as desired [47]. In this context, it is important to note that many online gamers consider teasing and aggressive behavior to be a fundamental part of the gaming experience [48,49]. One possible explanation for this phenomenon can be attributed to normative belief theories that have shown that normalization of aggression may perpetuate aggression [44,49]

Regarding H2 (“Boys were more likely to be affected by cyberbullying and cybervictimization through online gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic, while girls were more likely to be affected by social media”), we found an unexpected relationship. The possible reason our data show a positive association between social media and cyberbullying by the female sex might could be related to the nature of social media use by girls [50]. Some studies have shown that cyberbullying on social media is more common among girls, as they usually use it to share personal information and obtain feedback from other users, while other girls use social media to attack and denigrate other girls [17,18]. Studies have shown that girls are more likely to attack other girls via social media, while boys are generally more likely to use physical violence [51,52].

The results of this survey are consistent with the findings from the scientific literature: In general, boys seem to use the Internet for online gaming and girls for social media use. Some differences concern the time spent online: girls seem to spend more time than boys on social media [35,37,50], and girls use social media via smartphones and computers, while boys spend more time playing online games [14,50]. Girls use social media primarily to compare themselves with their peers, increase their visibility, and receive positive feedback [18,53,54]. Girls seem to be afraid of comments concerning their weight [15,55,56].

This increased release of personal information by girls and their possible increased vulnerability to the comments of others would make them more vulnerable to cyberbullying and cybervictimization [15,18,43]. Boys seem to be less interested in the possible comments of others. This could be inferred from their different uses of social media, which their parents also report: they search for information about sports and games on social platforms [57].

Online gamers consider online games more masculine. This could be one of the explanations for different experiences in cyberbullying [47,58].

Regarding H3 (“Time spent online mediates the relationship between social media and online gaming and exposure to cyberbullying during the COVID-19 pandemic”), we confirmed that the problem of cyberbullying perpetrated and suffered online has been exacerbated with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the increase in online use outside of school hours has made adolescents even more vulnerable to this phenomenon. Girls, in particular, are even more susceptible to social media, and boys are even more susceptible to online gaming. These findings are consistent with some studies (e.g., ref. [59]) that the extended time adolescents have spent using social networks and playing online gaming during the pandemic has led to an increase in incidents of online violence, with social media in particular posing a risk for girls and online gaming for boys [22,60].

As previously reported, young people were already spending many hours on social networks or playing online games before the pandemic. During the pandemic, there was a considerable increase, making them more vulnerable to phenomena such as cyberbullying, both as perpetrators and victims [61,62].

With this in mind, we hypothesized that online games and social media, which are usually the common venue for cyberbullying [56,63], have been influenced by an increase in the number of hours spent online, which, according to some studies, has led adolescents, both boys and girls, to overuse the Internet and lose control over this use, leading to problematic use that results in dynamics such as cyberbullying [64,65].

These hypotheses may explain why our study highlighted a key role of time spent online as a risk factor for cyberbullying during the pandemic. Our findings are supported by some studies [39] that emphasize that, in the context of online games, one of the protective factors for experiences such as cyberbullying is low weekly online game use.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

This is a cross-sectional study that does not clarify the causal directions of the relationship between the variables. The data were collected at a single point in time; it was difficult to determine the temporal sequence of events in the cross-section, and the data could not capture the dynamic nature of behavior. Although a large sample size is an advantage, it could also pose a risk when interpreting the results. Significant results, especially those with small effect sizes, should be interpreted with caution as they could be influenced by a large sample. Further studies on these topics are needed, but the present study provides a useful basis for exploring the role of social media and online gaming.

It will certainly be interesting to explore the role of parents in controlling children’s social media and online game use in future research, as it is known in the literature that parental control plays a crucial role as a protective factor [39,46].

It will certainly be interesting in the future to use standardized questionnaires to be able to proceed with more complex analyses carried out using Hayes’ models, which have provided important insights into the use of social media and online gaming by adolescents, providing interesting pointers to continue research in this direction. Furthermore, using measures with more than two categories can help in understanding the complexity of the phenomenon of cyberbullying and cybervictimization.

6. Conclusions

The data obtained from this study can help provide more accurate evidence on the link between social media, online gaming, and cyberbullying as people spend more time online during the pandemic.

These data allow us to understand the crucial role of social media and online gaming in cyberbullying and the need to educate about their conscious use. The results also provide us with information on how we should act in schools, as Italian Law no. 71/2017 on cyberbullying requires the creation of measures to prevent and combat cyberbullying [66]. It would, therefore, be important to create pathways that take into account these two virtual environments, which represent a risk factor recognized in the literature.

The law also requires that there be cyberbullying officers in each school to coordinate prevention efforts and be a point of contact for cyberbullying incidents involving students in the school for which they are responsible [67]. Knowledge of the virtual environments in which their students operate would allow them to better understand the dynamics of cyberbullying and intervene preventively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and M.A.Z.; methodology, M.R. and C.M.; formal analysis, M.R.; data curation, C.M. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M. and M.A.Z.; supervision, M.A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Pavia (no. 097/22).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics committee and informed consent do not authorise the sharing of data with third parties.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- David-Ferdon, C.; Hertz, M.F. Electronic media, violence, and adolescents: An emerging public health problem. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Electronic bullying among middle school students. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S22–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.K.; Mahdavi, J.; Carvalho, M.; Fisher, S.; Russell, S.; Tippett, N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.J.; Connor, J.P.; Scott, J.G. Integrating traditional bullying and cyberbullying: Challenges of definition and measurement in adolescents–A review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, C.; Cain, J. The emerging issue of digital empathy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.C.; Conklin, B. The balancing act: The role of transnational habitus and social networks in balancing transnational entrepreneurial activities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 1045–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareki, A.; Altuna, J.; Martínez-de-Morentin, J.I. Fake digital identity and cyberbullying. Media Cult. Soc. 2023, 45, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.D.D.M.; Shapka, J.F.; Domene, M.H. Gagné Are cyberbullies really bullies? An investigation of reactive and proactive online aggression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInroy, L.B.; Mishna, F. Cyberbullying on online gaming platforms for children and youth. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2017, 34, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, L. Cyberbullying in social media and online games among Chinese college students and its associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, Z.; Permatasari, C.B.; Mani, L. Cyber Violence and Bullying in Online Game Addiction: A Phenomenological Study. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2022, 100, 1428–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.C.; Chiu, C.H.; Miao, N.F.; Chen, P.H.; Lee, C.M.; Chiang, J.T.; Pan, Y.C. The relationship between parental mediation and Internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 57, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker, C.L.; Skew, A.J.; Kelly, Y.J.; Sacker, A. Media use, sports participation, and well-being in adolescence: Cross-sectional findings from the UK household longitudinal study. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Slater, A. Facebook and body image concern in adolescent girls: A prospective study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, J.C.; Reich, S.M. “It’s just a lot of work”: Adolescents’ self-presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, W.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; King, N.; Walsh, S.D.; Boer, M.; Donnelly, P.D.; Pickett, W. Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felice, G.; Burrai, J.; Mari, E.; Paloni, F.; Lausi, G.; Giannini, A.M.; Quaglieri, A. How do adolescents use social networks and what are their potential dangers? A qualitative study of gender differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCouteur, A.; Feo, R. Real-time communication during play: Analysis of team-mates’ talk and interaction. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, M.E.; Welch, K.M. Virtual warfare: Cyberbullying and cyber-victimization in MMOG play. Games Cult. 2017, 12, 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hong, J.S.; Yoon, J.; Peguero, A.A.; Seok, H.J. Correlates of adolescent cyberbullying in South Korea in multiple contexts: A review of the literature and implications for research and school practice. Deviant Behav. 2018, 39, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notar, C.E.; Padgett, S.; Roden, J. Cyberbullying: A review of the literature. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejmelka, L.; Matkovic, R. Online interactions and problematic internet use of Croatian students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Information 2021, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying, 2nd ed.; Corwin Press: Dallas, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 140–160. [Google Scholar]

- Smahel, D.; Machackova, H.; Mascheroni, G.; Dedkova, L.; Staksrud, E.; Ólafsson, K.; Livingstone, S.; Hasebrink, U. EU Kids Online 2020: Survey Results from 19 Countries; EU Kids Online: Hamburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.F.; Wachs, S. Adolescents’ cyber victimization: The influence of technologies, gender, and gender stereotype traits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raacke, J.; Bonds-Raacke, J. MySpace and Facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkhize, S.; Gopal, N. Cyberbullying perpetration: Children and youth at risk of victimization during COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2021, 10, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C. What are the characteristics of cyberbullying victims and perpetrators among South Korean students and how do their experiences change? Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 113, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslandes, S.F.; Coutinho, T. The intensive use of the internet by children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19 and the risks for self-inflicted violence. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 2479–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee DM, H.; Al-Anesi MA, L.; Al-Anesi SA, L. Cyberbullying on social media under the influence of COVID-19. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2022, 41, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Giannitto, N.; Squarcia, A.; Neglia, C.; Argentiero, A.; Minichetti, P.; Principi, N. Development of psychological problems among adolescents during school closures because of the COVID-19 lockdown phase in Italy: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 8, 628072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, M.A.; Marinoni, C.; Pedroni, S. Bullismo e cyberbullismo ai tempi del COVID-19. Riv. Di Lingue E Lett. Straniere E Cult. Mod. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Williams, K.; Dincelli, E. Got phished? Internet security and human vulnerability. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xue, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, T. Examining the impact of COVID-19 lockdown in Wuhan and Lombardy: A psycholinguistic analysis on Weibo and Twitter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N. Gender differences in associations between digital media use and psychological well-being: Evidence from three large datasets. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemenager, T.; Neissner, M.; Koopmann, A.; Reinhard, I.; Georgiadou, E.; Müller, A.; Hillemacher, T. COVID-19 lockdown restrictions and online media consumption in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marr, K.L.; Duell, M.N. Cyberbullying and cybervictimization: Does gender matter? Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinoni, C.; Zanetti, M.A.; Caravita, S.C. Sex differences in cyberbullying behavior and victimization and perceived parental control before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 530–560. [Google Scholar]

- Festl, R.; Vogelgesang, J.; Scharkow, M.; Quandt, T. Longitudinal patterns of involvement in cyberbullying: Results from a Latent Transition Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Agrawal, S. Perceived vulnerability of cyberbullying on social networking sites: Effects of security measures, addiction and self-disclosure. Indian Growth Dev. Rev. 2021, 14, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J.; Prinstein, M.J. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beres, N.A.; Frommel, J.; Reid, E.; Mandryk, R.L.; Klarkowski, M. Don’t you know that you’re toxic: Normalization of toxicity in online gaming. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry, A.C.; Sorrentino, A.; Farrington, D.P. Cyberbullying and cybervictimization versus parental supervision, monitoring and control of adolescents’ online activities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 96, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, L. Queer Female of Color: The Highest Difficulty Setting There Is? Gaming Rhetoric as Gender Capital; University of Oregon: Eugene, OR, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cappa, C.; Jijon, I. COVID-19 and violence against children: A review of early studies. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z.; Neill, J.T. I’m just trolling: The role of normative beliefs in aggressive behaviour in online gaming. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, M.; Overå, S. Are there differences in video gaming and use of social media among boys and girls?—A mixed methods approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.R.; Guerra, N.G. Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.M.; Chesney-Lind, M.; Stein, N. Patriarchy matters: Toward a gendered theory of teen violence and victimization. Violence Against Women 2007, 13, 1249–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolenbaugh, M.; Foley-Nicpon, M.; Young, R.; Tully, M.; Grunewald, N.; Ramirez, M. Parental perceptions of gender differences in child technology use and cyberbullying. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 1657–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. ‘If the rise of the TikTok dance and e-girl aesthetic has taught us anything, it’s that teenage girls rule the internet right now’: TikTok celebrity, girls and the Coronavirus crisis. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 23, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, D.L.; Bell, B.T. “It’s better saying I look fat instead of saying you look fat”: A Qualitative Study of UK Adolescents’ Understanding of Appearance-Related Interactions on Social Media. J. Adolesc. Res. 2024, 39, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, J.J.; Tng, G.Y.; Yang, S. Effects of social media and smartphone use on body esteem in female adolescents: Testing a cognitive and affective model. Children 2020, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.L. Intersecting oppressions and online communities: Examining the experiences of women of color in Xbox Live. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marraudino, M.; Bonaldo, B.; Vitiello, B.; Bergui, G.C.; Panzica, G. Sexual differences in internet gaming disorder (IGD): From psychological features to neuroanatomical networks. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.Y.; Fox, J. Men’s harassment behavior in online video games: Personality traits and game factors. Aggress. Behav. 2016, 42, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlett, C.P.; Simmers, M.M.; Roth, B.; Gentile, D. Comparing cyberbullying prevalence and process before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 161, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hee, C.; Jacobs, G.; Emmery, C.; Desmet, B.; Lefever, E.; Verhoeven, B.; Hoste, V. Automatic detection of cyberbullying in social media text. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Choi, Y.J. Comparison of Cyberbullying before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcum, C.D.; Higgins, G.E.; Ricketts, M.L. Potential factors of online victimization of youth: An examination of adolescent online behaviors utilizing routine activity theory. Deviant Behav. 2010, 31, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.C.; Chiu, C.H.; Lee, C.M.; Chen, P.H.; Miao, N.F. Predictors of the initiation and persistence of Internet addiction among adolescents in Taiwan. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittichai, R.; Smith, P.K. Information technology use and cyberbullying behavior in south Thailand: A test of the Goldilocks hypothesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, M.A.; Caravita, S.C.S. Il Cyberbullismo come emergenza sociale: Indicazioni per l’intervento alla luce della nuova normativa. Maltrattamento E Abus. All’infanzia 2018, 20, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiuliano Intra, F.; Nasti, C.; Massaro, R.; Perretta, A.J.; Di Girolamo, A.; Brighi, A.; Biroli, P. Flexible Learning Environments for a Sustainable Lifelong Learning Process for Teachers in the School Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).