Effect of Adolescent Health Policies on Health Outcomes in India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

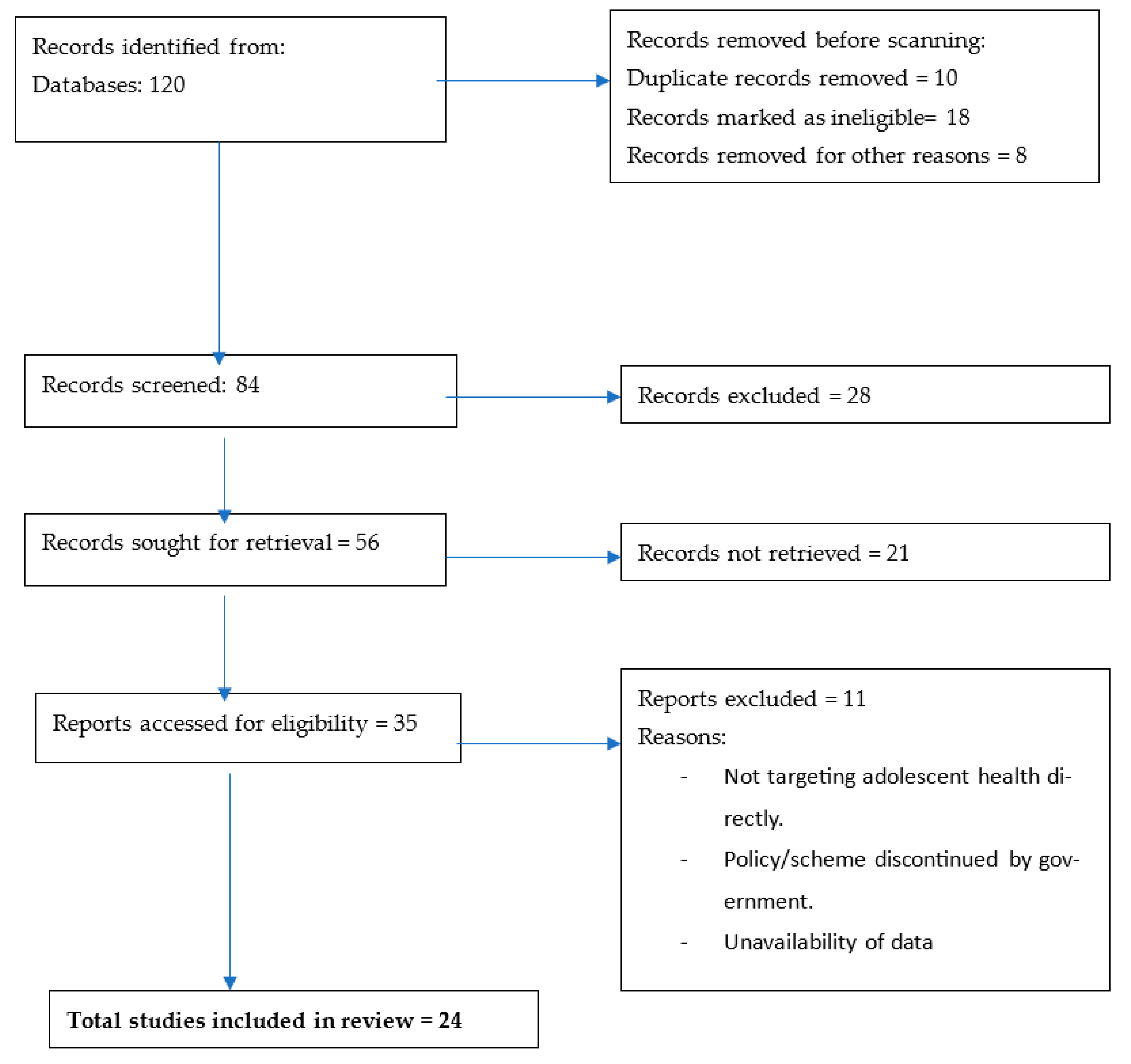

2. Methods

2.1. Study Areas

2.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.3. Quantitative Data Analysis

3. Results

- Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Strategy (2005). This strategy aims to provide a comprehensive framework for offering various sexual and reproductive health services to adolescents. It encompasses a core package of services, including preventive, promotive, curative, and counseling services to cater to the specific needs of this age group.

- Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) 2014. This strategy, called the National Adolescent Health Program, has significantly expanded the scope of adolescent health programming in India. It no longer confines itself solely to sexual and reproductive health but includes nutrition, injuries and violence (including gender-based violence), non-communicable diseases, mental health, and substance misuse. The strength of this program lies in its health-promoting approach, shifting from clinic-based services to prevention and promotion, reaching adolescents in their own environments, such as schools, families, and communities.

- School Health Program 2020. The objectives of this program are focused on various aspects, including improving nutrition, enhancing vaccination status, sexual and reproductive health, promoting mental health, preventing injuries and violence (including GBV), and addressing substance misuse. Additionally, this program is open to including other relevant topics as determined in consultation with other national stakeholders.

3.1. The Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health (ARSH) Strategy 2005

- Strengths (S):

- Targeted interventions in schools. The strategy showed effective strategies for providing health interventions specifically tailored to the needs of adolescents within educational settings, which can be crucial in reaching a large number of young individuals.

- Addressed sexual violence. The policies recognized and addressed the issue of sexual violence among adolescents, indicating a proactive approach toward safeguarding their well-being.

- Confidential and secure adolescent clinics. Establishing confidential and secure clinics for adolescents indicated efforts to provide a safe and private space for seeking healthcare services, encouraging adolescents to access healthcare without fear of judgment or disclosure.

- Weaknesses (W):

- Health service focus and limited focus on awareness. The analysis identified a lack of awareness among adolescents about available health services and resources, which hinders their ability to access necessary care.

- Not addressing societal barriers. The strategy may not have adequately addressed societal barriers such as cultural norms, stigma, or discrimination that can impede adolescents from seeking healthcare or engaging in preventive behaviors.

- Not addressing substance abuse. The policies may not have adequately tackled the issue of substance abuse among adolescents, which could have negative implications for their health and well-being.

- Opportunities (O):

- Female-friendly clinics. There is potential for the development of clinics that are specifically designed to cater to the needs and preferences of female adolescents, ensuring inclusivity and accessibility of healthcare services for this group.

- Free nutritional supplements. Providing free nutritional supplements to adolescents can help address nutritional deficiencies, improving overall health and well-being in this age group.

- Education about early pregnancy. Implementing educational programs focusing on early pregnancy can raise awareness and empower adolescents to make informed decisions about reproductive health.

- Threats (T):

- Societal taboos are prevalent and difficult to configure. Deep-rooted societal taboos and norms may pose challenges in designing and implementing effective policies that address sensitive issues related to adolescent health.

- The scarcity of financial resources poses a significant threat to the successful implementation of strategies and related interventions on a national scale.

3.2. Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) 2014

- Strengths (S):

- Extensive monitoring and promotion. The policies demonstrate a strong commitment to monitoring and promoting adolescent health, ensuring that the interventions are effectively implemented and reaching the target population.

- Special training for health workers. The policies recognize the importance of adequately trained healthcare workers who possess the necessary skills to address the unique healthcare needs of adolescents.

- Additional focus on substance abuse. The policies have placed emphasis on tackling the issue of substance abuse among adolescents, indicating a proactive approach to addressing this significant health concern.

- Weaknesses (W):

- Low utilization of clinics, both by adolescents and parents. There may be reluctance among adolescents and their parents to utilize healthcare clinics for reasons such as stigma, lack of awareness, or fear of judgment.

- Limited NGO involvement. The limited involvement of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in implementing and supporting the policies could potentially impact the reach and effectiveness of the interventions.

- Lack of privacy in clinics. Inadequate privacy measures in healthcare clinics may discourage adolescents from seeking healthcare services, particularly for sensitive issues, leading to reduced access to necessary care.

- Opportunities (O):

- Weekly supplementation scheme. Implementing a weekly supplementation scheme for essential nutrients, along with regular assessment, can improve the overall nutritional status of adolescents, promoting their health and well-being.

- Counseling for substance abuse, tobacco use, etc. Integrating counseling services as part of the policies can help address substance abuse and tobacco use, providing support and resources for adolescents seeking to overcome these challenges.

- Special menstrual hygiene scheme. Introducing a dedicated scheme for menstrual hygiene can improve access to menstrual products, education, and support for adolescent girls, positively impacting their health and development.

- Threats (T):

- Human resources. A shortage of trained healthcare personnel and other human resources may limit the effective implementation and execution of the policies.

- Logistics supply. Challenges in logistics and supply chain management may hinder the timely delivery of healthcare services, medications, and resources to the target population.

- Infrastructure. Inadequate healthcare infrastructure, including clinics and facilities, could pose challenges to providing quality healthcare services to adolescents.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Adolescent Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Adolescents: Health Risks and Solutions. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/60561/file/adolescents-health-risks-solutions-2011.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- IAAH. International Association for Adolescent Health. 2023. Available online: https://iaah.org/about/ (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- UNICEF. Empowering Adolescent Girls and Boys in India. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/india/what-we-do/adolescent-development-participation (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Collin, P. Youth Civic Engagement: Building Bridges between Youth Practice and Policy. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/11921/file (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Nandita Babu, M.F. Adolescent Health and Well-Being: Issues, Challenges, and Current Status in India. In Handbook of Health and Well-Being: Challenges, Strategies and Future Trends; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.; Francis, K.L.; Dashti, S.G.; Patton, G. Child marriage and the mental health of adolescent girls: A longitudinal cohort study from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India. Lancet Reg. Health-Southeast Asia 2023, 8, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarna, A.; Porwal, A.; Ramesh, S.; Agrawal, P.K.; Acharya, R.; Johnston, R.; Khan, N.; Sachdev, H.P.S.; Nair, K.M.; Ramakrishnan, L.; et al. Characterisation of the types of anaemia prevalent among children and adolescents aged 1–19 years in India: A population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagurunathan, C.; Umadevi, R.; Rama, R.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Adolescent health: Present status and its related programmes in India. Are we in the right direction? J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2015, 9, LE01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Joshi, P.; Ghosh, A.; Areendran, G. Assessing biome boundary shifts under climate change scenarios in India. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 34, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaghta, M.A.; Elwalda, A.; Mousa, M.M.; Erkan, I.; Rahman, M. SWOT analysis applications: An integrative literature review. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2021, 6, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.M. Adolescent health in India: Need for more interventional research. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2016, 4, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Strategic Directions for Improving Adolescent Health in South-East Asia Region. 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205917/B4771.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Barua, A.; Watson, K.; Plesons, M.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Sharma, K. Adolescent health programming in India: A rapid review. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roudsari, R.L.; Javadnoori, M.; Hasanpour, M.; Hazavehei, S.M.M.; Taghipour, A. Socio-cultural challenges to sexual health education for female adolescents in Iran. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 11, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Munea, A.M.; Alene, G.D.; Debelew, G.T.; Sibhat, K.A. Socio-cultural context of adolescent sexuality and youth friendly service intervention in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthmainnah Nurmala, I.; Siswantara, P.; Rachmayanti, R.D.; Devi, Y.P. Implementation of Adolescent Health Programs at Public Schools and Religion-Based Schools in Indonesia. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, jphr.2021.1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USAIDS. The DHS Program STATcompiler. 2023. Available online: https://www.statcompiler.com/en/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- WHO. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women. 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341337 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- UNICEF. Child Marriage: Latest Trends and Future Prospects. 2018. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-marriage-latest-trends-and-future-prospects/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- MHFW. National Noncommunicable Disease Monitoring Survey (NNMS) 2017–18. 2018. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/data-reporting/india/india-nnms-2017-18-factsheet.pdf?sfvrsn=a3c7547b_1&download=true (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- WHO. Adolescent Health: The Missing Population in Universal Health Coverage. 2019. Available online: https://pmnch.who.int/resources/publications/m/item/adolescent-health---the-missing-population-in-universal-health-coverage (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- UNFPA. Universal Health Coverage and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. My Body is My Body, My Life is My Life: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Young People in Asia and the Pacific. 2021. Available online: https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/asrh_factsheet_7_uhc.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Mazidi, M.; Banach, M.; Kengne, A.P.; Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration Group. Prevalence of childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Asian countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2018, 14, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Policy/Scheme | Year | Coverage | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health (ARSH) Strategy | 2005 | Introduced in New Delhi and later implemented in all states | MoHFW * |

| Kishori Shakti Yojana | 2007 | Odisha | MWCD ** |

| National Adolescent Health Strategy | 2014 | New Delhi | UNFPA *** |

| National Adolescent Health Program Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) | 2014 | All states of India | MoHFW * |

| Beti Bachao Beti Padhao Yojana | 2015 | Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Bihar and Delhi | MWCD ** |

| Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls | 2017 | 200 selected districts in India | MWCD ** |

| National Policy for Rare Diseases | 2017 | All states of India | MoHFW * |

| Poshan Scheme for Holistic Nourishment | 2018 | Rajasthan | MWCD ** |

| School Health Program | 2020 | Government schools in all districts | MoHFW * |

| DHS Indicators | 2005/2006 % | 2015/2016 % | 2019/2021 % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family planning | |||

| Married adolescents currently using any method of contraception | 13 | 14.9 | 28.1 |

| Married adolescents currently using any modern method of contraception | 6.9 | 10 | 18.8 |

| Unmet need for family planning for adolescents | 13.9 | 12.9 | 9.4 |

| Demand for family planning satisfied by modern methods | 7.3 | 26.9 | 40.9 |

| Violence | |||

| Sexual violence committed by a husband/partner in the last 12 months | 11.6 | 5.5 | 6.1 |

| Physical violence committed by a husband/partner in the last 12 months | 21.8 | 16.3 | 16.4 |

| Women first married by the exact age of 15 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

| Access to health | |||

| Adolescent girls’ access to health: Problems obtaining permission to attend treatment | 9.3 | 20.8 | 16.5 |

| Adolescent girls’ access to health: Problems obtaining money for treatment | 16.3 | 26.2 | 22.4 |

| Adolescent girls’ access to health: Problems with distance to health facilities | 24.6 | 31.5 | 24.2 |

| Adolescent girls’ access to health: Problems that there may not be a female provider | 21 | 41.6 | 34.3 |

| No health insurance—Adolescent girls | No data | 83 | 74.5 |

| No health insurance—Adolescent boys | No data | 81.5 | 73 |

| Behaviors | |||

| Condom use at last higher-risk sex (with a non-marital, non-cohabiting partner) [Adolescent boys] | 33.4 | 47.9 | 56.6 |

| Condom use at last higher-risk sex (with a non-marital, non-cohabiting partner) [Adolescent girls] | 20 | 35.3 | 62 |

| Adolescent boys who smoke any type of tobacco | 57.3 | 29.7 | 34.4 |

| Adolescent girls who smoke any type of tobacco | 3.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Nutrition | |||

| Adolescent girls who are overweight or obese according to BMI (≥25.0) | 2.4 | 4.2 | 5.4 |

| Adolescent boys who are overweight or obese according to BMI (≥25.0) | 1.7 | 4.8 | 6.6 |

| Adolescent girls with any anemia | 55.8 | 54.1 | 59.1 |

| Adolescent boys with anemia | 30.2 | 29.2 | 31.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sahadevan, S.; Dar Iang, M.; Dureab, F. Effect of Adolescent Health Policies on Health Outcomes in India. Adolescents 2023, 3, 613-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3040043

Sahadevan S, Dar Iang M, Dureab F. Effect of Adolescent Health Policies on Health Outcomes in India. Adolescents. 2023; 3(4):613-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahadevan, Sayooj, Maureen Dar Iang, and Fekri Dureab. 2023. "Effect of Adolescent Health Policies on Health Outcomes in India" Adolescents 3, no. 4: 613-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3040043

APA StyleSahadevan, S., Dar Iang, M., & Dureab, F. (2023). Effect of Adolescent Health Policies on Health Outcomes in India. Adolescents, 3(4), 613-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3040043