Asthma Prevalence in Adolescent Students from a Portuguese Primary and Secondary School

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Collection and Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2002. Available online: http://www.ginasthma.com/ (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Nieto-Fontarigo, J.J.; González-Barcala, F.J.; San José, E.; Arias, P.; Nogueira, M.; Salgado, F.J. CD26 and Asthma: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogliani, P.; Calzetta, L.; Matera, M.G.; Laitano, R.; Ritondo, B.L.; Hanania, N.A.; Cazzola, M. Severe Asthma and Biological Therapy: When, Which, and for Whom. Pulm. Ther. 2020, 6, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scarlata, S.; Incalzi, R.A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. In Pathy’s Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 542–554. ISBN 978-1-119-48428-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, G.A.; Kiley, J.P.; Gibbons, G.H. Generating evidence to inform an update of asthma clinical practice guidelines: Perspectives from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lai, K.; Shen, H.; Zhou, X.; Qiu, Z.; Cai, S.; Huang, K.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Lin, J.; Hao, C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Cough—Chinese Thoracic Society (CTS) Asthma Consortium. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 6314–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavord, I.D.; Beasley, R.; Agusti, A.; Anderson, G.P.; Bel, E.; Brusselle, G.; Cullinan, P.; Custovic, A.; Ducharme, F.M.; Fahy, J.V.; et al. After asthma: Redefining airways diseases. Lancet 2018, 391, 350–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakou, E.; Kaniaris, E.; Filiou, E.; Vasileiadis, I.; Katsaounou, P.; Tzortzaki, E.; Koulouris, N.; Koutsoukou, A.; Rovina, N. Acute Severe Asthma in Adolescent and Adult Patients: Current Perspectives on Assessment and Management. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjerg, A.; Hedman, L.; Perzanowski, M.; Wennergren, G.; Lundbäck, B.; Rönmark, E. Decreased importance of environmental risk factors for childhood asthma from 1996 to 2006. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strina, A.; Barreto, M.L.; Cooper, P.J.; Rodrigues, L.C. Risk factors for non-atopic asthma/wheeze in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2014, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asher, M.I.; Keil, U.; Anderson, H.R.; Beasley, R.; Crane, J.; Martinez, F.; Mitchell, E.A.; Pearce, N.; Sibbald, B.; Stewart, A.W.; et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): Rationale and methods. Eur. Respir. J. 1995, 8, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, E.D.; Hurd, S.S.; Barnes, P.J.; Bousquet, J.; Drazen, J.M.; FitzGerald, M.; Gibson, P.; Ohta, K.; O’Byrne, P.; Pedersen, S.E.; et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 143–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.R.A.; Cousens, S.N.; de Góes Siqueira, L.F.; Alves, F.M.; D’Angelo, L.A.V. Crowding: Risk factor or protective factor for lower respiratory disease in young children? BMC Public Health 2004, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pivniouk, V.; Gimenes-Junior, J.A.; Ezeh, P.; Michael, A.; Pivniouk, O.; Hahn, S.; VanLinden, S.R.; Malone, S.P.; Abidov, A.; Anderson, D.; et al. Airway administration of OM-85, a bacterial lysate, blocks experimental asthma by targeting dendritic cells and the epithelium/IL-33/ILC2 axis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, J.A.; Janssen, I.; Bruner, M.W.; Hossain, A.; Pickett, W. Asthma incidence and risk factors in a national longitudinal sample of adolescent Canadians: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2014, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mallol, J.; Crane, J.; von Mutius, E.; Odhiambo, J.; Keil, U.; Stewart, A. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Three: A global synthesis. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2013, 41, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, C.C.; Havstad, S.L.; Ownby, D.R.; Joseph, C.L.M.; Sitarik, A.R.; Biagini Myers, J.; Gebretsadik, T.; Hartert, T.V.; Khurana Hershey, G.K.; Jackson, D.J.; et al. Pediatric asthma incidence rates in the United States from 1980 to 2017. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, I.C.; Caeiro, E.; Ferro, R.; Camacho, R.; Câmara, R.; Grinn-Gofroń, A.; Smith, M.; Strzelczak, A.; Nunes, C.; Morais-Almeida, M. Spatial and temporal variations in the Annual Pollen Index recorded by sites belonging to the Portuguese Aerobiology Network. Aerobiologia 2017, 33, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camarinha, C.P. Prevalence and Determinants of Uncontrolled Asthma in Portugal: A National Population-Based Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/40006 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Sa-Sousa, A.; Morais-Almeida, M.; Azevedo, L.F.; Carvalho, R.; Jacinto, T.; Todo-Bom, A.; Loureiro, C.; Bugalho-Almeida, A.; Bousquet, J.; Fonseca, J.A. Prevalence of asthma in Portugal—The Portuguese National Asthma Survey. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2012, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendes, Z.; Madeira, A.; Costa, S.; Inácio, S.; Vaz, M.; Araújo, A.T.; Luis, A.S.; de Almeida, M.M. Avaliação do controlo da asma através do Asthma Control Test TM aplicado em farmácias portuguesas. Rev. Port Imunoalergol. 2010, 18, 313–330. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, C.J. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flores, P. Atividade Física Adaptada a crianças e adolescentes asmáticos e com excesso de peso ou obesidade. Rev. Cent. Form. Assoc. Esc. Amarante E Baião 2015, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ivey, M.A.; Simeon, D.T.; Juman, S.; Hassanally, R.; Williams, K.; Monteil, M.A. Associations between climate variables and asthma visits to accident and emergency facilities in Trinidad, West Indies. Allergol. Int. 2001, 50, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gergen, P.J.; Mitchell, H.; Lynn, H. Understanding the seasonal pattern of childhood asthma: Results from the national cooperative inner-city asthma study (NCICAS). J. Pediatr. 2002, 141, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.W. Climate Change and Allergy, An Issue of Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America, E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-323-79386-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ehara, A.; Takasaki, H.; Takeda, Y.; Kida, T.; Mizukami, S.; Hagisawa, M.; Yamada, Y. Are high barometric pressure, low humidity and diurnal change of temperature related to the onset of asthmatic symptoms? Pediatr. Int. 2000, 42, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farouque, A.S.; Walker, R.; Erbas, B. Thunderstorm asthma epidemic—management challenges experienced by general practice clinics. J. Asthma 2021, 58, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.-R.; Lin, C.-H.R.; Tsai, J.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Tsai, T.-A.; Tsai, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-C.; Liu, T.-Y.; Tsai, C.-M.; Chen, C.-C.; et al. A Multifactorial Evaluation of the Effects of Air Pollution and Meteorological Factors on Asthma Exacerbation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Lacasse, M.; Armstrong, M. Climate Data to Undertake Hygrothermal and Whole Building Simulations Under Projected Climate Change Influences for 11 Canadian Cities. Data 2019, 4, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lau, S.; Illi, S.; Sommerfeld, C.; Niggemann, B.; Bergmann, R.; von Mutius, E.; Wahn, U. Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens and development of childhood asthma: A cohort study. Lancet 2000, 356, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldizen, F.C.; Sly, P.D.; Knibbs, L.D. Respiratory effects of air pollution on children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2016, 51, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, G.D.; Kipen, H.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Balmes, J.; Brook, R.D.; Cromar, K.; Matteis, S.D.; Forastiere, F.; Forsberg, B.; Frampton, M.W.; et al. A joint ERS/ATS policy statement: What constitutes an adverse health effect of air pollution? An analytical framework. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1600419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norbäck, D.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Qian, H.; Sun, Y.; Sundell, J.; et al. Onset and remission of childhood wheeze and rhinitis across China—Associations with early life indoor and outdoor air pollution. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relvas, H.; Miranda, A.I. An urban air quality modeling system to support decision-making: Design and implementation. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2018, 11, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; Policies, E.O.; On, H.S.; Barros, P.P.; Machado, S.R.; de Simões, J.A. Portugal: Health System Review; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Di Filippo, P.; Dodi, G.; Ciarelli, F.; Di Pillo, S.; Chiarelli, F.; Attanasi, M. Lifelong Lung Sequelae of Prematurity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.C.; Dahlin, A.; Wang, A.L. The Role of Environmental Risk Factors on the Development of Childhood Allergic Rhinitis. Children 2021, 8, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá-Sousa, A.; Jacinto, T.; Azevedo, L.F.; Morais-Almeida, M.; Robalo-Cordeiro, C.; Bugalho-Almeida, A.; Bousquet, J.; Fonseca, J.A. Operational definitions of asthma in recent epidemiological studies are inconsistent. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2014, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozier, M.J.; Zahran, H.S.; Bailey, C.M. Assessing health outcomes, quality of life, and healthcare use among school-age children with asthma. J. Asthma 2019, 56, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Magalhães, M.; Pereira, A.M.; Sa-Sousa, A.; Morais-Almeida, M.; Azevedo, I.; Azevedo, L.F.; Fonseca, J.A. Asthma control in children is associated with nasal symptoms, obesity, and health insurance: A nationwide survey. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 26, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Beebe, J.; Lopez, L.; Faux, S. A Qualitative Exploration of Asthma Self-Management Beliefs and Practices in Puerto Rican Families. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2010, 21, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, J.R.; Rhee, H.; Norton, S.A.; Butz, A.M. Perceptions and experiences underlying self-management and reporting of symptoms in teens with asthma. J. Asthma 2017, 54, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.E.; Bragada, J.A.; Bragada, J.P.; Coelho, J.P.; Pinto, I.G.; Reis, L.P.; Fernandes, P.O.; Morais, J.E.; Magalhães, P.M. Structural Equation Modelling for Predicting the Relative Contribution of Each Component in the Metabolic Syndrome Status Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.K.; Scheff, P.A.; Hryhorczuk, D.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Ross, M.; Persky, V. Prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases in an adolescent population: Association with gender and race. Ann. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. 2001, 86, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, O.; Bahmer, T.; Rabe, K.F.; von Mutius, E. Asthma transition from childhood into adulthood. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, A.L.; Green, R. Transition for adolescents and young adults with asthma. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | Age (Mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 1222 | 14.44 ± 1.63 |

| Male | 587 | 14.38 ± 1.67 |

| Female | 635 | 14.49 ± 1.59 |

| Group comparison significance | p = 0.17 | p = 0.19 |

| Asthma Diagnosed by a Doctor | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

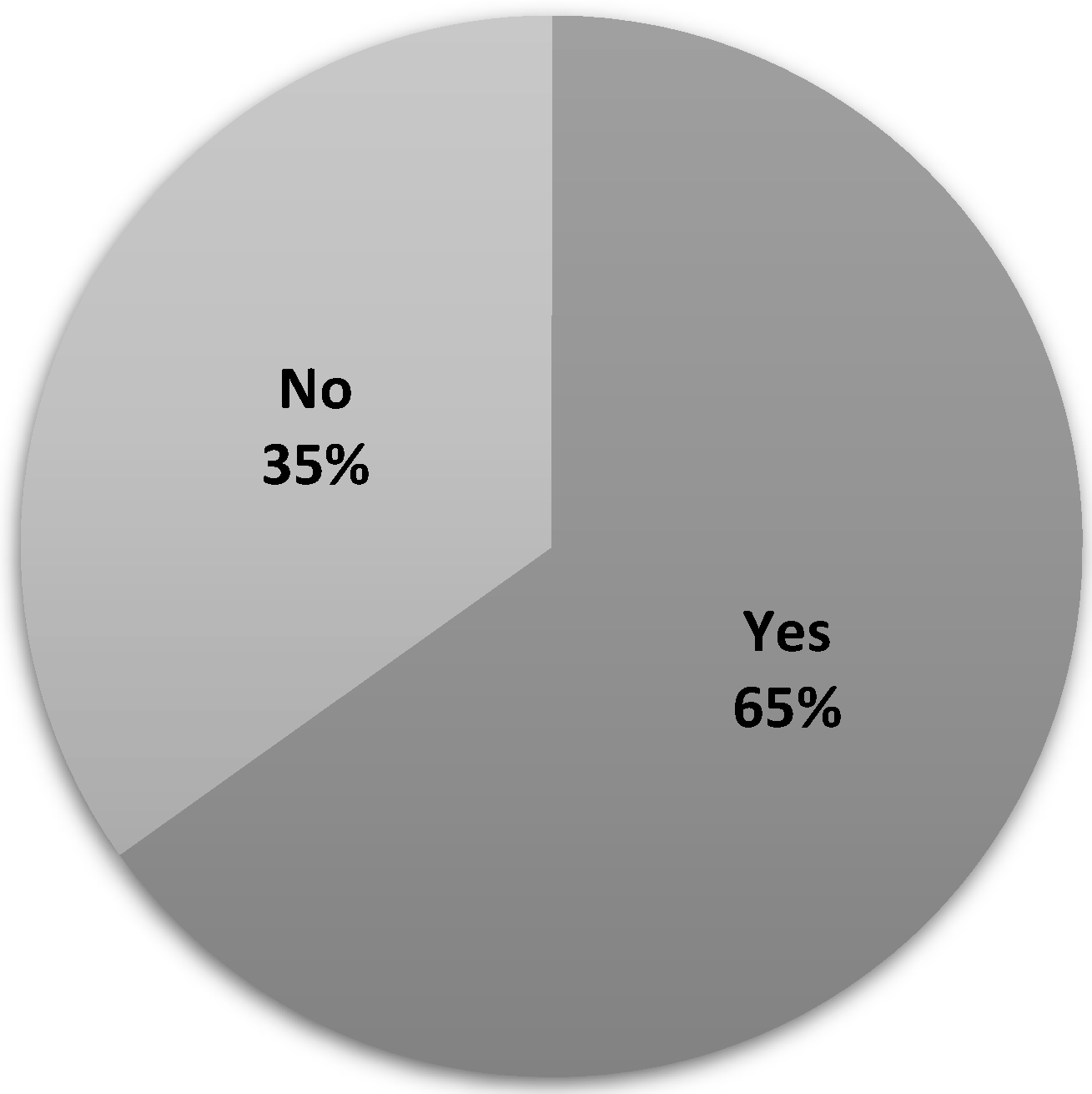

| N | % | N | % | |

| No | 536 | 91.3 | 577 | 90.9 |

| Yes | 51 | 8.7 | 58 | 9.1 |

| p | 0.50 | |||

| Total Symptoms Associated with Asthma | Non-Asthmatic | Asthmatic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| 0 | 774 | 69.5 | 8 | 7.3 |

| 1 | 176 | 15.8 | 14 | 12.8 |

| 2 | 90 | 8.1 | 17 | 15.6 |

| 3 | 48 | 4.3 | 24 | 22.0 |

| 4 | 18 | 1.6 | 18 | 16.5 |

| 5 | 5 | 0.4 | 20 | 18.3 |

| 6 | 1 | 0.1 | 6 | 5.5 |

| 7 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 1.8 |

| Total | 1113 | 100 | 109 | 100 |

| Typology of Symptoms Associated with Asthma | N/% | Non-Asthmatic | Asthmatic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Wheezing | N | 253 | 86 | 32 | 69 |

| % | 74.6 | 25.4 | 31.7 | 68.3 | |

| Going to the doctor for shortness of breath | N | 252 | 87 | 27 | 74 |

| % | 74.3 | 25.7 | 26.7 | 73.3 | |

| Get tired easily | N | 198 | 141 | 62 | 39 |

| % | 58.4 | 41.6 | 61.4 | 38.6 | |

| Wheezing after exercise | N | 257 | 82 | 54 | 47 |

| % | 75.8 | 24.2 | 53.5 | 46.5 | |

| Dry cough after exercise | N | 217 | 122 | 55 | 46 |

| % | 64 | 36 | 54.5 | 45.5 | |

| Dry cough at night | N | 285 | 54 | 73 | 28 |

| % | 84.1 | 15.9 | 72.3 | 27.7 | |

| Sleeps poorly due to shortness of breath | N | 301 | 38 | 62 | 39 |

| % | 88.8 | 11.2 | 61.4 | 38.6 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flores, P.; Teixeira, J.E.; Leal, A.K.; Branquinho, L.; Fonseca, R.B.; Silva-Santos, S.; Batista, A.; Encarnação, S.; Monteiro, A.M.; Ribeiro, J.; et al. Asthma Prevalence in Adolescent Students from a Portuguese Primary and Secondary School. Adolescents 2022, 2, 381-388. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2030029

Flores P, Teixeira JE, Leal AK, Branquinho L, Fonseca RB, Silva-Santos S, Batista A, Encarnação S, Monteiro AM, Ribeiro J, et al. Asthma Prevalence in Adolescent Students from a Portuguese Primary and Secondary School. Adolescents. 2022; 2(3):381-388. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores, Pedro, José E. Teixeira, Anna K. Leal, Luís Branquinho, Rui Brito Fonseca, Sandra Silva-Santos, Amanda Batista, Samuel Encarnação, António M. Monteiro, Joana Ribeiro, and et al. 2022. "Asthma Prevalence in Adolescent Students from a Portuguese Primary and Secondary School" Adolescents 2, no. 3: 381-388. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2030029

APA StyleFlores, P., Teixeira, J. E., Leal, A. K., Branquinho, L., Fonseca, R. B., Silva-Santos, S., Batista, A., Encarnação, S., Monteiro, A. M., Ribeiro, J., & Forte, P. (2022). Asthma Prevalence in Adolescent Students from a Portuguese Primary and Secondary School. Adolescents, 2(3), 381-388. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2030029