Abstract

Background: Mental health during a person’s adolescence plays a key role in setting the stage for their mental health over the rest of their life. Hence, initiatives that promote adolescents’ wellbeing are an important public health goal. Helping others can take a variety of forms, and the literature suggests that helping others can positively impact a person’s wellbeing. However, there is a lack of data that synthesizes the impact of helping others on adolescents’ wellbeing. Therefore, this review aims to synthesize the available evidence related to helping others and to youth wellbeing. Methods: A scoping review search was undertaken with no date restrictions. CINAHL, Medline and PyschINFO, were searched for studies that analyzed the relationship between helping others and youth mental health. Results: Data from 213 papers were included in the scoping review. Three main themes were observed: (1) the relationship between helping others and mental health outcomes among youths (positive and negative); (2) factors associated with youth engagement in prosocial behavior (facilitators and barriers); (3) the impact of interventions related to helping others, and to youth mental health (positive and negative). Conclusions: An overwhelmingly positive relationship exists between youth prosocial behavior and its influence on youth mental health.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is an important stage in the development of a person’s mental health. When considering pressing public health concerns, the mental health of young people has become a critical topic of discussion. The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly added additional stressors for youths—challenges such as difficulties associated with distance education and limited social interaction [1]. Globally, data suggests that up to one in five young people are impacted by mental health challenges, and that 50% of these challenges start by the age of 14 [2]. This reiterates the importance of timing, in supporting young people’s mental health. Unfortunately, it appears that many youths are not receiving the mental health care they need [3]. Young people who do not receive the mental health care they need face a higher risk from the consequences of diminished mental health and difficulties carrying out meaningful lives [4]. These challenges may also take a notable toll on valuable public health resources and programs. This data highlights the importance of prioritizing the mental health of adolescents, especially given the likely detrimental mental health impact resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Social environments and feelings of belonging are deeply intertwined concepts, which is significant when considering how mental health is impacted by societal factors [5]. Furthermore, positive outlook, strong self-esteem, confidence in one’s ability to cope with adversity, and strong social cohesion can all be conceptualized as mental health and wellbeing traits [6]. By connecting these important societal-level impacts and mental health traits, a relationship can be seen between social environments and positive mental health traits. Moreover, evidence shows that positive emotions and connections early in life play an important role in achieving a better quality of life over the course of a lifetime [7].

Helping others has been defined as a voluntary act that aims to benefit and support others [8,9]. This can take various forms, such as formal volunteer roles or informally helping a stranger on the street. Regardless of the form, helping others has a positive impact on mental health [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. It is important to note that helping others has been identified by a variety of often interchangeable terms in the literature, which include prosocial behavior, altruism and volunteerism [10].

Several social psychology and developmental theories propose that helping others is a key foundation for youth development [10,11]. Moreover, it is agreed that promoting the virtue of helping others from a young age helps achieve positive psychosocial outcomes across the course of a lifetime. Many papers have highlighted the mental health benefits associated with helping others: these benefits include increased coping abilities, reduced depression and stress [13], happiness [14,15], increased levels of self-esteem, improved academic performance and overall better social connections [16,17]. This highlights the plethora of evidence supporting the benefits for the mental health of young people, in helping others. It is important to note that much of this evidence is in the form of independent studies. Thus, there is a crucial need to synthesize these findings systematically, and to generate further evidence, which will significantly contribute to knowledge of the impact of helping others (and other prosocial behavior) on youth mental health.

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to synthesize and present the evidence related to helping others and youth mental health. The findings of this review inform key recommendations for future research in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

We undertook a scoping review of the scientific literature on how prosocial behavior is related to the mental health of young people, by using Arksey & O’Malley’s [18] five-stage scoping review framework.

2.1. Stage 1: Identify the Research Question

According to Arksey & O’Malley [18], the first step to conducting a scoping review is to identify the research question. Therefore, with the aim of synthesizing existing knowledge in this area, our scoping review addressed the following research question:

What is known from existing literature about the virtue of helping others and its relevance to youth mental health?

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

Our search strategy was developed through a preliminary search, which allowed us to better understand search terms and keywords, and with the support of a subject expert librarian (Table 1). We searched the databases CINAHL (EBSCOhost), MEDLINE (Ovid) and PsycINFO.

Table 1.

Terms Used in the Literature Search.

2.3. Stage 3: Selection of Literature: Inclusion Criteria

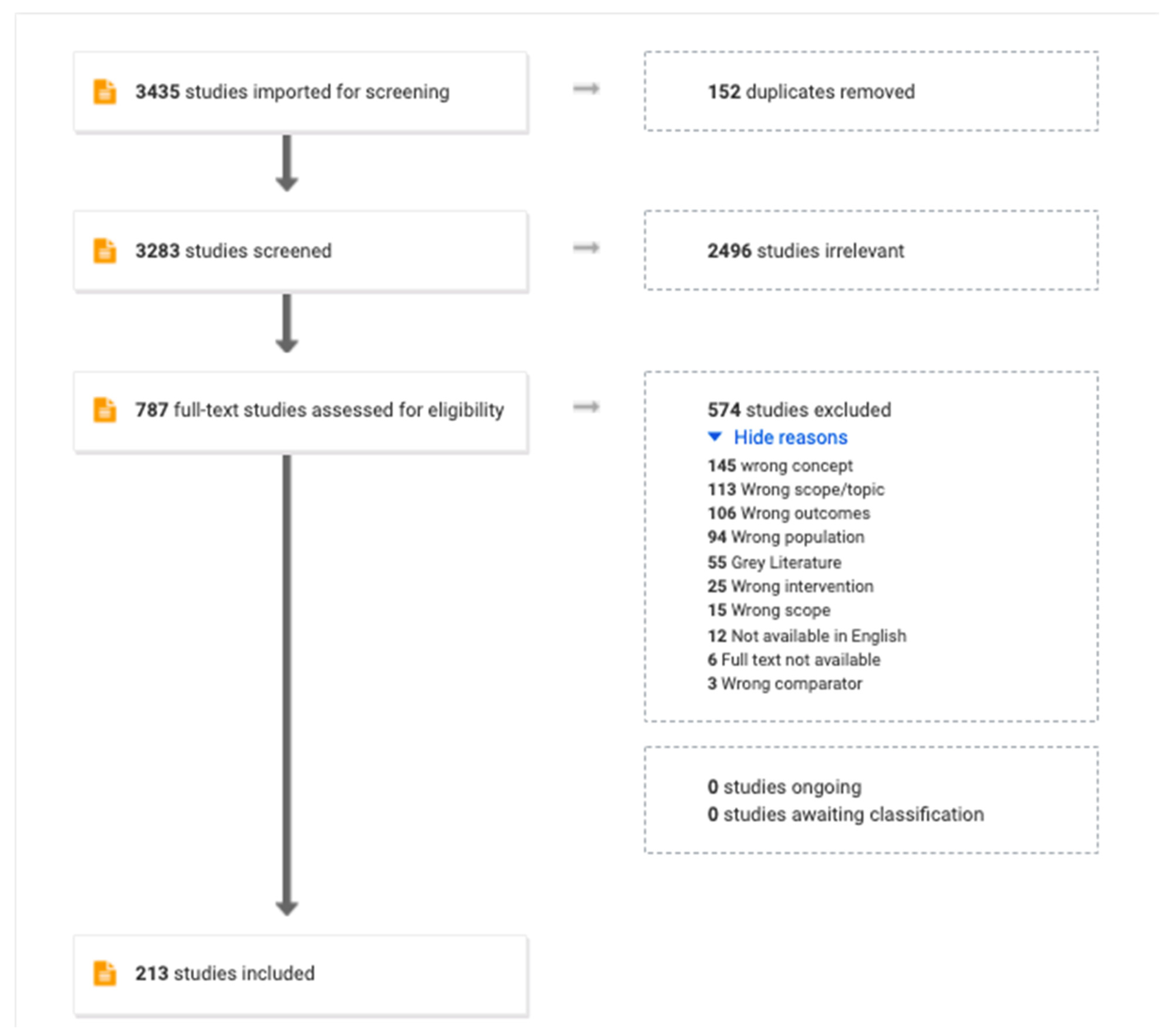

A total of 3435 papers identified by our search strategy were imported into the review software Covidence [19] for screening. Of this number, 152 duplicates were removed, leaving 3283 papers to be screened. We conducted a title and abstract screening based on the following inclusion criteria outlined in 2.3.1 below.

2.3.1. Types and Scope of Studies

This review includes quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies from all research settings and geographic locations that discussed youth experiences of helping others, highlighting mental health outcomes. We sought to include studies which discussed the facilitators and barriers for youths to engage in helping others, and the mental health component of helping others. Papers that analyzed the impact of helping others, interventions on youth mental health, and the relationship between these two concepts were also included.

2.3.2. Key Concepts

This review captures key concepts related to mental health, including mental wellbeing and mental health outcomes (such as resilience, self-efficacy, stress and coping, self-esteem, social cohesion, quality of life and others), and mental health issues (such as depression, anxiety and emotional disturbance). Concepts related to helping others, including prosocial behavior, altruism, volunteerism, giving, community engagement services and acts of kindness, were also considered.

2.3.3. Participants

The review focused on young people aged between 10 and 24 years, including all gender identities, with or without mental health issues.

Following this, 787 full-text papers were assessed, and 574 more studies were excluded because the papers discussed the wrong concept, wrong scope, wrong outcomes, wrong population, wrong comparator, were from the gray literature, were not available in English or did not have a full text available. We provide a PRISMA flow chart delineating these steps in Figure 1. To capture as many data as possible, and to account for diversity, our review did not apply any date or geographic restrictions. We focused exclusively on peer-reviewed literature. We excluded papers that did not have a translated English version available, and articles that were part of the gray literature. Furthermore, we did not include papers that only discussed outcomes related to physical wellbeing.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

2.4. Stage 4: Data Extraction

A data charting form was co-developed by the review team (SH and NB). We uploaded the extraction tool onto Covidence to record the authors, title, journal, publication year, country, study objective, study design, context, participant characteristics (age, gender, sample size) and findings. Two reviewers independently extracted data for each article. Each extracted article was reviewed by a third independent reviewer if there was any conflict or disagreement.

2.5. Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

Our data were summarized using the number of publications in each year, the region of publication and the study design. Our findings are presented under three themes, determined by our focus of studies included in the review: (1) the relationship between helping others and mental health outcomes among youths; (2) factors associated with youth engagement in prosocial behavior (facilitators and barriers); (3) the impact of interventions related to helping others, and to youth mental health (positive and negative). Each article was coded based on its content in relation to its relevant major theme(s). After completing the analysis, key findings and existing data gaps were identified.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Identified Studies

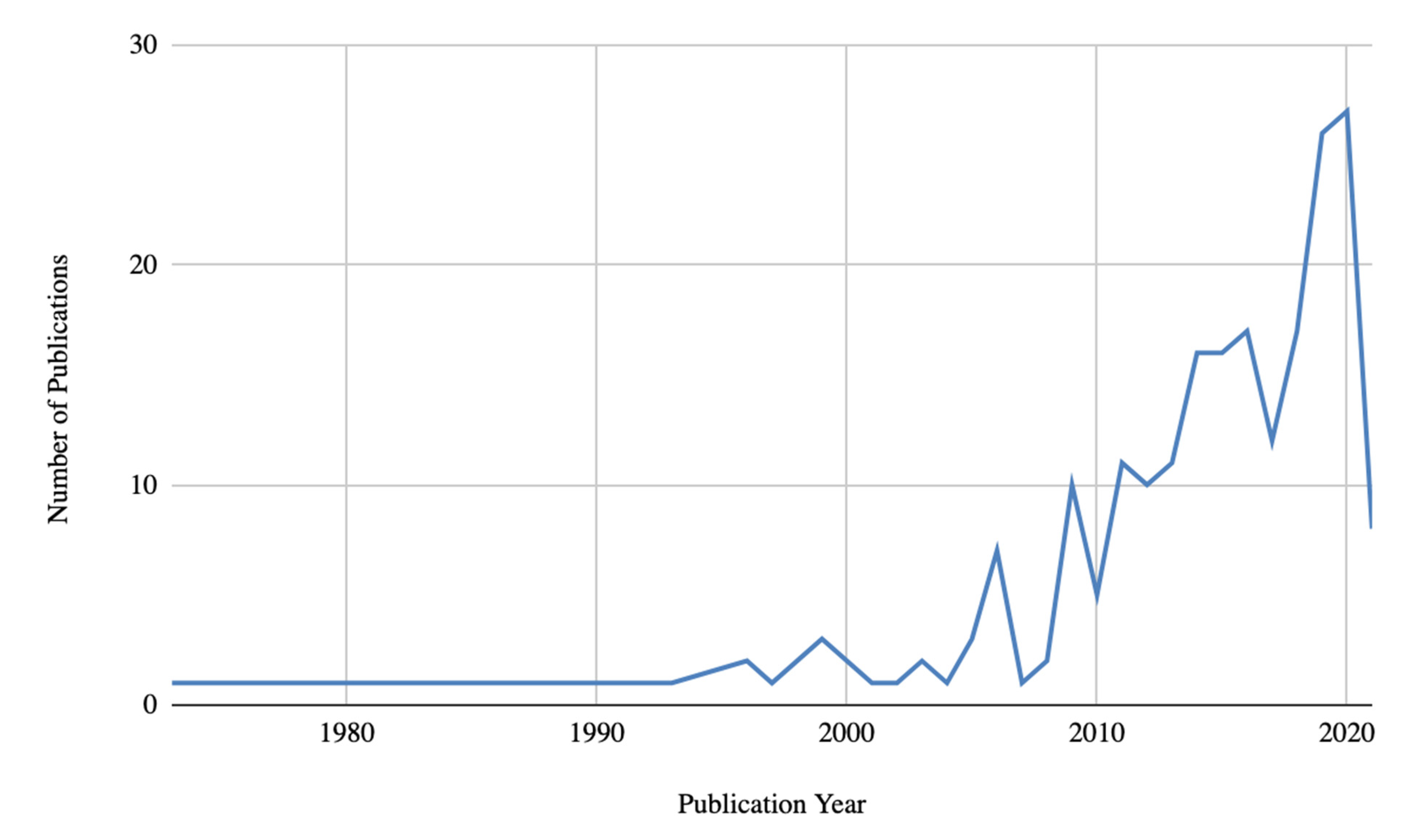

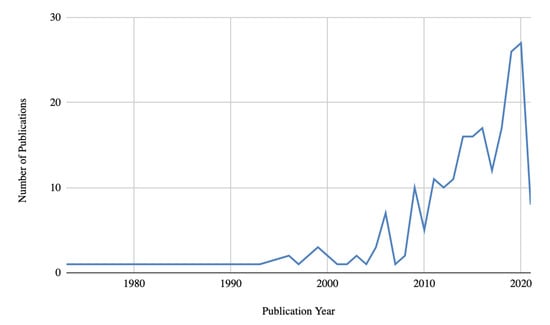

Of the 213 studies included, 83% (n = 176) studies were published between 2010 and 2021 (Figure 2). The majority of the studies were from the United States (n = 93), the United Kingdom (n = 16), Australia (n = 15), the Netherlands (n = 13), China (n = 11) and Canada (n = 10). A small number of studies were from other regions of the world (Table 2). Most of the studies included in this review were quantitative (n = 159), and the remainder included qualitative (n = 21), mixed methods (n = 19) and review papers (n = 14). The sample sizes of the studies captured in this review had a wide range; 91% of the studies had a sample size ≥30. Most of the studies (n = 198, 93%) recruited youths identifying as both males and females; 15 studies included either only male or only female participants (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Number of Publications per Year (1973–2021).

Table 2.

Number of Studies from Different Countries/Regions.

Table 3.

Genders Distribution Included in the Studies (n = 213).

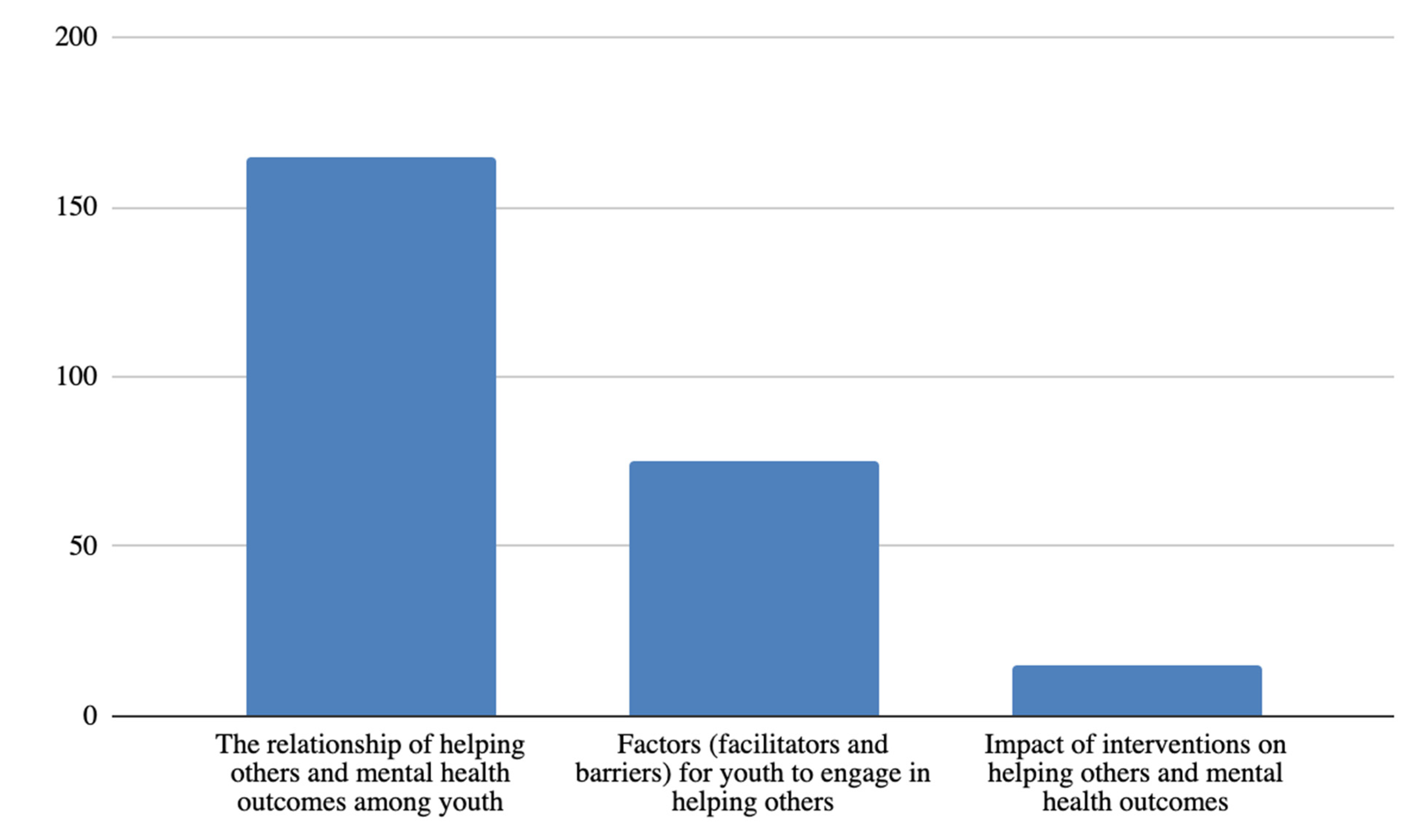

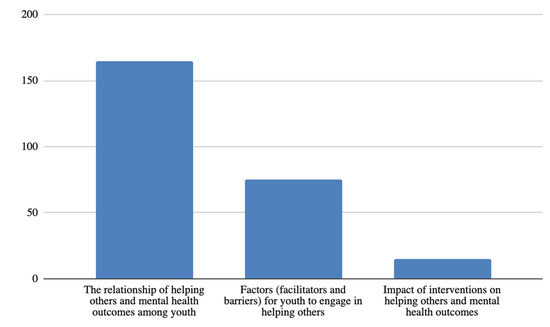

3.2. Frequency of Themes

Figure 3 shows the number of studies that discussed information relevant to the key themes of this study. Of the studies included in this review, 189 discussed the relationship between helping others and mental health outcomes among youths, including the experiences of youths who engaged themselves in prosocial behavior; 75 studies presented factors that motivated, and/or barriers for youths to engage in prosocial behavior; and 16 of the studies showcased interventions that influenced prosocial behavior and mental health among this population.

Figure 3.

Frequency of Themes in the Literature.

3.3. Major Themes

3.3.1. Relationship between Helping Others and Mental Health Outcomes among Youths

Positive Outcomes

This review found a plethora of positive mental health impacts associated with prosocial behavior among youths. Several studies have also identified positive benefits related to mental health outcomes among youths. These benefits included positive thinking, forms of satisfaction, increased positive effects, social network, school performance, mental health impact, feelings for others, volunteer opportunities, personal traits, thoughts about the future, societal positionality of youths, self-efficacy, religion and spirituality, avoiding substance abuse, family impact and community impact.

Greene, et al. [20], found that peers who were caregivers showed increased optimism and positive coping, compared to non-caregiver peers. Three other studies found that prosocial behavior was associated with satisfaction [21] and a higher level of general life satisfaction [22,23].

Additionally, prosocial behavior was associated with increased positive effects [24,25,26]. Furthermore, it was found that prosocial orientation was correlated with later engagement in enrichment activities, educational attainment and psychological adjustment [27]. Studies have also shown an association of prosocial behavior with increased self-worth [28], acceptance [29] and higher self-esteem [30,31].

Studies have reported that the social network of young people was profoundly impacted by prosocial behavior [32]. New friendships were made [33,34,35,36], and prosocial friendships were uniquely associated with positive adaptations for high-risk youths [37]. Moreover, in terms of the composition of the network, children with more diverse social networks reported fewer depressive symptoms, higher self-rated health, fewer behavioral problems and more prosocial behavior [38]. Hanghoj, et al. [39], and Poon [40] both reported the theme of belonging, experienced by young people who were engaged in prosocial endeavors. Additionally, peer acceptance [41], social satisfaction [33,42] and supportive relationships were also reported as positive outcomes of engaging in prosocial behavior [43,44]. Prosocial behavior also impacted young people’s thoughts on sharing, as some became more open to sharing [45]. Two studies [46,47] found that prosocial behavior positively impacted young people’s connections in school. Likewise, prosocial behavior was shown to be influenced by and impacted by peers [48,49,50,51] and by the social position of youths, which included community or religious activities that they participated in [47,52,53].

A few studies revolved around the relationship between young people’s prosocial behavior and school performance. Lu, et al. [33], found that helping others improved academic freedom and school satisfaction. Other studies showed a positive relationship between prosocial behavior and academic achievement [54,55,56] and that school programs provided youths with the opportunity for prosocial interactions [57,58].

Our review indicated that prosocial behavior was linked to improved wellbeing [59,60,61], positive emotions [33], decreased depressive symptoms [28,62,63,64,65], psychological engagement [66], positive changes in adolescents’ mental health [56,67], resilience [68], increased stress tolerance [69], decreased negative psychological outcomes [60,65] and lower prevalence of health-risk behavior [70]. Prosocial peer treatment was associated with increased acceptance, less anxiety [29,63] and decreased loneliness [71]. One study found that youths experiencing seasonal affective disorder (SAD) were engaged more in peer-helping than youths without SAD [72]. Prosocial behavior impacted the way young people felt about others, by evoking emotional responses to others in need [73], and empathy [74,75,76,77]. Williams & Metz [78] found that prosocial behavior was beneficial for youths who were at risk of negative outcomes (criminal activity). Emam [79] found that children with low levels of prosocial behavior were more likely to display higher levels of emotional and behavioral challenges.

Interestingly, differing from earlier findings, prosocial behavior was seen more in boys’ schools [80]. Prosocial behavior was also linked to optimism in adversity [81]. Moreover, future optimism was linked to a significantly higher probability of reporting frequent prosocial bystander behavior [31]. Different types of self-efficacy connected to prosocial behavior were discovered through this review, including empathic self-efficacy [82,83], community service self-efficacy [84] and higher self-efficacy [69].

When considering the process of volunteering, youths described having opportunities and recognition [85], the feeling that their contributions were noticed [86], and purposeful social contribution [87,88] as reasons for favoring prosocial behavior. Prosocial behavior was also found to be protective against adolescent substance abuse [89,90], and to promote healthy, engaged and productive functioning in young adulthood [91].

Themes around the community and prosocial behavior showed that youths who used community-based social service agencies other than mental health or parole were 2.43 times more likely to be employed [92]. Furthermore, prosocial behavior was more strongly oriented toward in-group members [93] and natives than immigrants. Studies also found that higher levels of community acceptance were associated with higher baseline levels of adaptive/prosocial behavior [94,95]. Considering the broader societal level, Oliffe [96] suggested that changes in masculine ideals that were congruent with national identity were leading towards more prosocial ideas.

Lastly, engaging in prosocial behavior resulted in several positive impacts. The identified studies suggested that youths who engaged in prosocial behavior benefited from increased use of reappraisal [97], coping mechanisms [98], depression-prevention strategies [97,98,99], positive reappraisal [100], higher levels of intentional self-regulation [101], higher levels of strengths and lower levels of distress [102], higher levels of trust [103], passions, relational opportunities, sense of empowerment [104], increased awareness [105], happiness [21,60], positive self-identity [81,106], improved wellbeing [107,108], better morale [109] and positive and safe experiences [110,111]. Some other prosocial strategies involved youths encouraging self-help, and respecting the right of their peers not to seek help [112]. One study reported eudemonic contribution-to-others beliefs positively related to prosocial spending [113].

Negative Outcomes

There were also quite a few negative and neutral impacts associated with helping others, on youth mental health and substance use, personal traits, peers, support needs, social activities, family and gender.

In terms of negative influences on mental health, adolescents who experienced symptoms of depression and peer-rejection gave help less often [114,115], and were less motivated to help others, than were those with low-depressive symptoms [116,117]. Cui, et al. [118], found that peer unsupportive emotion socialization significantly predicted less prosocial behavior across time.

Additionally, young people with autism spectrum disorder [119] and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder displayed moderately lower prosocial behavior [120].

Greene, et al. [20], found that young adult caregivers were significantly more depressed and anxious than their non-caregiving peers. Additionally, Meehan, et al. [121], discovered that low prosocial behavior was directly associated with mental and physical health problems. Furthermore, when comparing the impacts of volunteering, lay disaster volunteers had higher levels of adverse mental health challenges compared to affiliated disaster volunteers [122]. Moreover, both lay and affiliated disaster volunteers had a higher prevalence of mental health challenges compared to the general population [122].

When considering substance abuse, organ donors showed higher rates of anxiety and alcohol-use disorders than normative samples in one or more study assessments [123]. In addition, Carter, et al. [124], found that adolescents with substance dependency disorder, in comparison to a normative national sample, showed lower levels of prosocial behavior.

Several personal traits have been negatively related to prosocial behavior. These traits include baseline confusion [125], anger [126], external forms of concrete thinking [127], avoidance coping [128], rule-breaking and aggressive behavior [129], increased sensitivity to social rejection [130], and age [131]. Interestingly, Feng, et al. [132], found that in cases of worsening mental health, due to the inability of the youths to engage in prosocial behavior, and to perceived high risks in their surroundings, altruism played a moderating role. In addition, Milledge, et al. [133], discovered that emotional distress did not significantly contribute to differences in prosocial behavior. However, Araujo, et al. [134], found that stressful life events acted as a barrier to prosocial behavior. The youths at risk of emotional disorder and vulnerability were those who rated themselves highly on the prosocial variables [135,136]. The work of Bang, et al. [46], suggested that volunteering was not a significant predictor of self-esteem. Further, Malamut, et al. [137], found that social popularity predicted lower levels of prosocial behavior. In terms of age, Wray-Lake, et al. [131] found that early-to-middle adolescents reported lower frequencies of prosocial moral judgements. He, et al. [138], suggested that the absence of prosocial behavior was not the same as the presence of psychological challenges.

When considering the social activities that youths engage in, one study found that prosocial behavior towards friends indirectly predicted more anxiety via connection with a best friend [139]. Furthermore, another study found that positive school experiences and school characteristics were not significantly associated with the probability of engaging in prosocial bystander behavior [31]. In terms of experiencing discrimination, findings suggest that discrimination experiences during adolescence may influence depressive symptoms and prosocial behavior up to a year later [140].

Regarding family-related themes, siblings of children with mental retardation [141] and mental illness [142] did not engage in more tangible aid or information-giving than siblings of children without disability. Helicopter-parenting was also found to be associated with decreased empathetic concern, perspective-taking and prosocial behavior in emerging adults [143]. We found inconsistent findings related to gender. Bot, et al. [144], found that boys had significantly more prosocial behavior problems compared to girls. Betancourt, et al. [95], discovered that female soldiers reported significantly lower levels of confidence and lower levels of prosocial attitudes.

3.3.2. Factors Associated with Youth Engagement in Prosocial Behavior

Facilitators

Several facilitators of helping others were identified by this scoping review. These facilitators were activities outside school, physical activity, personal, social, school, family, social status, healthcare and location.

In terms of activities outside school, extracurricular activities [46], community involvement or productive engagement [91], and education outside of the classroom [145] were seen as key themes. When considering the age of participants, youths who started employment at age 15 were found to be motivated towards prosocial behavior [146]. Furthermore, informative feedback to youths, while they were volunteering, was considered as an important factor [87]. With regard to volunteering, activity settings [147] and the type of placement were significant predictors of prosocial behavior [148]. One study found that only service in humanitarian organizations was beneficial [149]; however, specific volunteer opportunities, such as civic engagement [150,151,152] and mentoring [81], were also connected to prosocial behavior.

Various forms of physical activity were reported to be important facilitators: exercising or playing sports strenuously one to two, or three or more times per week [153], sport engagement [82], membership of a sports club and frequency of sports participation [154] were all themes in this domain.

Personal traits in youths, such as willingness to help others [155], moral identity [156], self-efficacy [126], character strengths [157], resilience [106,108,158,159], gratitude [22,83,160], derived pleasure [111], self-perception [161], values [162], coherence [163,164], low-to-neutral achievement [165], personal experience with voluntary activities [45] and female gender [166] were prominent factors in expressing prosocial attitudes [126]. In terms of spiritual and religious perspectives, youths with spiritual striving, a religious worldview [167] and high rates of religious orientation [31] appeared to be more involved with helping others. Studies also reported empathy [42,75,168,169], feeling distressed about others [170] and showing acts of kindness [26] to be facilitators associated with prosocial behavior.

The review highlighted several social elements as facilitators of prosocial behavior among youths, such as peer attachment [77,170], role modeling [48], support from friends [108,153,167], perceived social support [171,172], engagement in giving and sharing [95], and fewer discrimination experiences [140], as contributing positively towards prosocial behavior.

Several studies discussed factors related to school and the school environment, as being linked to prosocial behavior. These were: attending school [146], attending secondary schools [86], a greater sense of school connectedness [173], school engagement [167], university programs [174], strong support from teachers and achieving high grades [31], and the student’s relatedness needs [175].

Family factors, such as maternal warmth [139,176,177], parental supervision [167], grandparents’ involvement and closeness [22,176,178,179], family cohesion and social support [173], positive parenting [148], maternal social interaction [180], siblings of children with disabilities [181] and parental warmth [182] were associated with prosocial behavior and family cohesion [173]. Other significant factors were relationships within the family, including nurturing from the family [183], supportive parent–child relationships [184], secure parental attachment [171], parents’ technoference [182] and kinship foster families showing more prosocial behavior [148]. In terms of parental behavior, factors encouraging prosocial behavior included parents giving priority towards prosociality over achievement, and their role-modeling of prosociality [165]. Furthermore, egalitarian gender-role attitudes were associated with better prosocial behavior [185].

Some studies have concluded that perceptions of the social status of young people also play a role in demonstrating prosocial behavior. Factors such as popularity [186], young people with high social status [187], social integration and absorption [22], a lower degree of influence in class [39], sociocultural resources [173] and receiving high social support [180,188] were all related to social status and prosocial behavior. When considering social network facilitators, prosocial networks [189], greater perceptions of sociopolitical control [106,151] and micro-, mezzo-, and exo-system factors [106] were identified. Berndt, et al. [188], found that competition with friends during adolescence decreased as prosocial behavior towards friends increased.

The societal positionality of youths, such as being non-incarcerated [190] and living in a highly cohesive neighborhood [191], was linked to prosocial behavior. In terms of religion and spirituality, religious practices [167,192], relatively high spirituality and high intrapersonal strengths [193] and pre-dispositional guilt [194] were all connected with prosocial behavior.

Barriers

We identified a number of individual, family and social themes as barriers to helping others among youths. Personal factors as barriers were much observed in the review. Revisiting the discussion on gender and prosocial behavior, a study found that female gender acted as a barrier toward prosocial behavior [153]. Life-satisfaction growth [172], social anxiety [59] and anger [126] appeared to be negatively correlated with reciprocal giving and prosocial behavior in adolescence.

Regarding family factors, lower maternal warmth [121], foster parent stress [148] and maternal depression [191] were connected to lower levels of prosocial behavior. Interestingly, Evans & Smokowski [31] found that youths living in a two-parent family had a significantly lower probability of engaging in frequent prosocial bystander behavior compared to youths living in another type of family structure. A study by Profe, et al. [176] indicated that father involvement was not found to be associated with adolescent prosocial behavior.

When considering social behavior in line with consistent links between parental warmth and prosocial behavior, some youths may have had less positive socialization, and hence may have been less considerate, due to the types of parenting behavior to which they were exposed [121]. Problematic mobile phone use was negatively associated with selfless attitudes [195]. Van Hoorn, et al. [48], found that prosocial behavior decreased when peers displayed selfish behavior. Nelson, et al. [28], reported that a focus on fun, in the form of hedonistic and risk behavior, seemed to occur at the expense of positive aspects of development, such as prosocial behavior. Furthermore, some youths felt that helping others when in need was not their responsibility [196].

3.3.3. Interventions Related to Helping Others and Youth Mental Health

Fifteen studies highlighted interventions and their impact, in relation to prosocial behavior, on youth mental health. The interventions were quite diverse (Table 4), and included (I)ntegrative (E)ducational (I)ntervention of (A)ltruism (IEIA) [33], group psychosocial intervention for children (aged 12–18) of a parent with mental illness [197], the Mindfulness and Social–Emotional Learning Program (M-SEL) [114], Kind Acts intervention [26], education outside the classroom [145], the universal school-based intervention in enhancing resiliency [198], autonomy vs. acts of kindness intervention [199], the openness and trust Upward Bound Program [200], school-based, teacher-led life skills intervention [201], resilience training [202], OpenMinds: a peer-designed and facilitated mental health literacy program [174], school-based intervention targeting resilience protective factors [203] and evidence-based, trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) [204].

Table 4.

Interventions Related to Prosocial Behavior and Youth Mental Health.

Positive Outcomes

These interventions led to several positive impacts, including life satisfaction, positive emotions, self-efficacy, lower levels of mental health challenges, an increase in prosocial behavior, improved learning, beliefs about social development and autonomy. Positive life satisfaction was a theme that arose from several interventions, such as IEIA [33], group psychosocial intervention [197] and the M-SEL [114]. Interventions also led to positive emotions being experienced by youths, specifically the autonomy vs. acts of kindness intervention [200] and the openness and trust Upward Bound Program [200,202]. In terms of the effect of personal beliefs on behavior, self-efficacy was a theme in a study that tested life skills intervention [202]. Prosocial interventions also played a role in improving the learning of young people, such as their learning about communities, poverty, diversity, teamwork, at-risk populations and their own biases and upbringing [110]. The group psychosocial intervention for children (aged 12–18) of a parent with mental illness showed a statistically significant increase in mental health literacy [197]. Additionally, prosocial interventions showed that they could impact young people’s beliefs about social development wellbeing and autonomy [115].

Lower levels of mental health challenges were showcased in some studies, including the M-SEL Program [114], group psychosocial intervention [197], universal school-based intervention in enhancing resiliency [198] and Kind Acts intervention [26].

A few interventions reported an increase in prosocial behavior, such as M-SEL [114], education outside the classroom [145], group psychosocial intervention [197], universal school-based intervention targeting resilience [198] and autonomy support and act of kindness intervention [199].

Negative Outcomes

Given the benefits shown by prosocial interventions, it is also important to discuss studies that found a non-positive or neutral impact. OpenMinds showed no differences in helping attitudes [174]. Furthermore, a school-based intervention targeting resilience protective factors [203], school-based life skills intervention [201] and a trauma-based CBT [204] found no differences or improvement in participants’ prosocial behavior.

4. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify evidence that examined youths’ prosocial behavior and its relevance to their mental wellbeing. Our findings are presented under three categories: the relationship between helping others and mental health outcomes among youths (positive and negative); factors associated with youth engagement in prosocial behavior (facilitators and barriers); and the impact of interventions related to helping others, and to youth mental health (positive and negative).

Our review found several mental health benefits associated with young people who were engaged in prosocial behavior. These positive benefits could be seen through the identified mental health outcomes explored alongside prosocial behavior. Life satisfaction was a prevalent theme [21,22,23], indicating how prosocial behavior can instill a positive impact on young people’s perceptions of their life. Moreover, key findings around wellbeing [59,60,61], positive emotions [33] and positive changes in adolescents’ mental health [69] have further reiterated the positive mental health impacts linked to prosocial behavior. Some studies have even identified that prosocial behavior can decrease depressive symptoms [65,66] and lower the prevalence of depression [67]. This highlights the exciting potential for prosocial activities to be integrated with mental health support for young people with depression. On the other hand, there were also some negative findings, albeit that some of these findings were specific to certain populations of youths. For example, Greene, et al. [20], found that young people who were caregivers were more depressed than other young people who were non-caregivers. This may be due to the immense pressure and stresses that caregivers in general face on a daily basis. Furthermore, studies [115,116,189] have highlighted that young people who live with mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, show lower levels of prosocial behavior. This indicates how mental health conditions can act as a barrier to the process of engaging in prosocial behavior.

In terms of youth experiences of helping others, and the relationship of those experiences to mental health outcomes, findings around the positive impacts on youth social networks have been very common. Impacts such as social network expansion, companionship, sharing behavior and connections have been identified [35,36,47,48,49], thus highlighting how prosocial behavior has impacts beyond individual youth and change social networks. Positive emotions, such as happiness [21,62], positive self-identity [81,106] and morale [109] have been associated with helping others. In contrast, the review identified a few neutral and negative experiences. A study by Evans & Smokowski [31] found that positive school experiences and the characteristics of school were not related to young people engaging in prosocial behavior. This speaks to the notion that certain environmental factors that youths interact with on a daily basis likely have differing influences on their prosocial behavior. Young people who experienced discrimination went on to experience an impact on their prosocial behavior, up to one year later. This suggests how the negative experiences that youths face, and the behavior projected towards youths, can impact on the perceived virtue of helping others.

Recognizing facilitators and barriers is key to understanding what factors promote and reduce prosocial behavior among youths. Extracurricular activities have been cited in various studies [48,95,159,160] as a key facilitator for helping others. This indicates the importance of activities outwith formal schooling, and of how these activities contribute to promoting prosocial behavior. However, it is also necessary to acknowledge that factors relating to the school environment have also been seen as facilitators for prosocial behavior: specifically, factors such as school connectedness [171], having a program for university [174], school engagement [167], strong teacher support and academic performance [31], and students’ relatedness needs were all identified as facilitators for prosocial behavior. This contrasts with the finding noted above, that positive school characteristics and school experiences did not influence prosocial behavior [31]. In fact, these findings highlight the need to understand that the many different interactions and environments in which young people find themselves can all shape their prosocial behavior. This review also identifies the significance of structural family factors as a facilitator in promoting prosocial behavior. Family cohesion, parental—specifically maternal—and grandparental involvement have been reported as main facilitators of prosocial behavior [103,167,171,173,176,178,179,180]. Moreover, one study [165] demonstrated parenting styles such as prioritizing prosociality over achievement, or equally valuing achievement and prosociality as a facilitator of prosocial behavior. This indicates how families, through support, cohesion and positive parenting styles, can play a vital and dynamic role in nurturing in young people the virtue of helping others. On the other hand, this review revealed some of the family factors that act as barriers to prosocial behavior: for example, lower levels of maternal warmth [121], stress experienced by foster parents [148] and maternal depression [191]. These findings underline how the health of the family can negatively impact the prosocial behavior of young people.

In terms of gender, this review presents mixed findings, and was unable to determine the influence of sex and gender on prosocial behavior. Our findings also report diverse interventions with mixed outcomes on helping others and youth mental health. Educational, psychosocial, mindfulness and act of kindness interventions had an overwhelmingly positive impact on youths: for example, life satisfaction [33,114,197], experience of positive emotions [200] and improved learning [110,199]. However, there were a few interventions—such as school-based programs for resilience, and trauma-focused intervention—that showed no change, or even showed a reduction in prosocial behavior [204]. This indicates the need for interventions to be designed carefully, and the need to understand the context and culture of the settings in which they are being implemented, as they may have the potential to reduce the prosocial behavior of youths. Moreover, utilizing youths as valued stakeholders, and understanding what support and interventions would be beneficial for them when engaging in prosocial behavior, could prove helpful.

The relationship between helping others and mental health outcomes among youths was the most prevalent theme identified by this scoping review. Of the 213 studies, 159 (74.6%) had content that linked to this theme. The least common theme was the impact of interventions on helping others: only 16 of the 213 studies (7.5%) had content relating to this theme. We believe this theme was the least prevalent because of the complexities associated with creating an intervention and evaluating the impacts of the said intervention on prosocial behavior. More details pertaining to the various themes, and the number of studies captured within these themes, can be seen in Figure 3.

Concerning the attributes of the available evidence, one of the gaps identified was the lack of gender-based analysis, and using gender binary, i.e., the included studies considered the gender of youths as either male or female. There were no discussions or data provided on gender-diverse youths, or youths who did not identify within the confines of male or female definitions. Furthermore, the vast majority—nearly 75%—of included studies were quantitative in nature. In this review, we also realized that most studies (43.7%) were from the USA, while only 4.7% of the studies were from Canada. This suggested an imbalance in terms of the regional origin of these papers, as nearly half of the included studies were from the USA. We also observed the lack of evidence about the influence of social media and internet use on the development of prosocial behavior in youths between 10 and 24 years old.

Although a significant body of literature exists examining prosocial behavior and the mental health of youths, the gaps identified by this review outline some key recommendations for future research. It is necessary for studies to consider gender diversity, so that the impact of prosocial behavior can be better understood in a diverse population of youths. Furthermore, additional qualitative studies that explore the experiences of youths with different gender identities have the potential to provide additional insight into the prosocial experiences of youths. Furthermore, given the large proportion of studies from the USA, future studies should aim to study youths from other regional spaces as well, so that the perspectives of diverse cultures and settings can also be included. Researchers should also pay attention to exploring the association between social media use and prosocial behavior in children and youths. Finally, it is important that youths play a central role in the development of interventions focused on helping others, as this can allow space for their meaningful engagement and participation.

While the findings of this review contribute to a growing body of evidence identifying prosocial behavior and its relevance to youth mental wellbeing, it is also important to acknowledge the limitations of this review. A key limitation of this scoping review was that the studies were searched using limited databases: specifically, we only searched CINAHL, MEDLINE (Ovid) and PsychINFO. This could have potentially limited the studies we were able to retrieve; however, these databases are strongly aligned with the nature of this topic. Furthermore, our review did not include the gray literature, which may also have resulted in important findings not being considered. However, this review was well-planned to address these limitations. For example, we ensured the inclusion of a wide coverage of studies by not restricting the year of publication and geographic locations. This allowed us to capture the most relevant, comprehensive and scientific data from diverse cultures and settings.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this scoping review present an overview of evidence pertinent to prosocial behavior and youth mental health. This review stemmed from three themes, which were: the relationship between helping others and mental health outcomes among youths (positive and negative); factors associated with youth engagement in prosocial behavior (facilitators and barriers); and the impact of interventions related to helping others and to youth mental health (positive and negative). An overwhelmingly positive relationship was observed between young people helping others and the subsequent impact on mental health. There is a high burden of mental health issues among youths. The nurturing, in young individuals, of the virtue of helping others, and the engagement of youths in prosocial behavior, are measures which have the potential to enhance youth mental health and wellbeing.

This review provides a breadth of evidence that could lay the foundation for future interventional studies, systematic reviews and meta-analysis. This review also highlights the need to consider gender and cultural diversity in this area of research. The findings of this review will also help key stakeholders, including parents, families, educational institutions and healthcare providers, to understand the importance of social connectedness and the role of prosocial behavior in improving the mental wellbeing of youths.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; Methodology, S.H., E.O. and N.A.B.; Validation, S.H., E.O. and N.A.B.; Investigation, S.H., E.O. and N.A.B.; Formal Analysis, S.H., E.O. and N.A.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.H. and N.A.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.H., E.O. and N.A.B.; Visualization, S.H. and N.A.B.; Project Administration, S.H. and N.A.B.; Supervision, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data extracted and analyzed in this review is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our university librarian for assisting us in optimizing our search strategy for this scoping review. We would also like to acknowledge our student research volunteers who helped us with screening.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vaillancourt, T.; McDougall, P.; Comeau, J.; Finn, C. COVID-19 school closures and social Isolation in children and youth: Prioritizing relationships in education. FACETS 2021, 6, 1795–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Child and Adolescent Mental and Brain Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/Improving-the-mental-and-brain-health-of-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Lawrence, P.J.; Evdoka-Burton, G.; Waite, P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Child and Youth Health and Well-Being Indicators Project: CIHI and B.C. PHO Joint Summary Report. 39. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/444614/publication.html (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Moorfoot, N.; Leung, R.K.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Catalano, R.F. The longitudinal effects of adolescent volunteering on secondary school completion and adult volunteering. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2015, 9, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N.; Mussen, P.H. The Roots of Prosocial Behavior in Children, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 1989; ISBN 978-0-521-33190-6. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, G.; Forbes, E.E. Prosocial behavior and depression: A case for developmental gender differences. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2017, 4, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.M. Prosocial involvement as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 769158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UKEssays. Social Psychology Theories and Prosocial Behavior. Available online: https://www.ukessays.com/essays/psychology/social-psychology-theories-prosocial-4303.php (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Arthur, J.; Harrison, T.; Taylor-Collins, E.; Moller, F. A Habit of Service. Available online: https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/1581/projects/current-projects/a-habit-of-service (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Raposa, E.B.; Laws, H.B.; Ansell, E.B. Prosocial behavior mitigates the negative effects of stress in everyday life. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 4, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.W.K.; Zhang, Z.; Kim, T.Y. Volunteering and health benefits in general adults: Cumulative effects and forms. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, S.G. Its good to be good. Int. J. Pers.-Cent. Med. 2014, 1–53. Available online: https://unlimitedloveinstitute.org/downloads/ITS-GOOD-TO-BE-GOOD-2014-Biennial-Scientific-Report-On-Health-Happiness-Longevity-And-Helping-Others.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Laible, D.J.; Carlo, G.; Roesch, S.C. Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviors. Fac. Publ. Dep. Psychol. 2004, 27. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub/315 (accessed on 25 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Carlo, G. The study of prosocial behavior. In Prosocial Development; Padilla-Walker, L.M., Carlo, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-0-19-996477-2. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Covidence.Org. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Covidence: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.; Cohen, D.; Siskowski, C.; Toyinbo, P. The relationship between family caregiving and the mental health of emerging young adult caregivers. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 44, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S.D.R.; Sumari, M.; Md Khalid, N. Surviving the break-up: Teenagers’ experience in maintaining wellness and well-being after parental divorce. Asia Pac. J. Couns. Psychother. 2020, 11, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froh, J.J.; Kashdan, T.B.; Yurkewicz, C.; Fan, J.; Allen, J.; Glowacki, J. The benefits of passion and absorption in activities: Engaged living in adolescents and its role in psychological well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtek, P. Prosocial vs antisocial coping and general life satisfaction of youth with mild intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2018, 62, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashjian, S.M.; Rahal, D.; Karan, M.; Eisenberger, N.; Galván, A.; Cole, S.W.; Fuligni, A.J. Evidence from a randomized controlled trial that altruism moderates the effect of prosocial acts on adolescent well-being. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Bauer, K.; Sengsavang, S. Fairness, prosociality, hypocrisy, and happiness: Children’s and adolescents’ motives for showing unselfish behavior and positive emotions. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 37, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, L.E.; Trew, J.L. If it makes you happy: Engaging in kind acts increases positive affect in socially anxious individuals. Emotion 2013, 13, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Rubin, K.H.; Cen, G.; Gao, X.; Li, D. Sociability and prosocial orientation as predictors of youth adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study in a Chinese sample. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2002, 26, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.; Willoughby, B.; Rogers, A.; Padilla-Walker, L. “What a view!”: Associations between young people’s views of the late teens and twenties and indices of adjustment and maladjustment. J. Adult Dev. 2015, 22, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, J.C. Prosocial Peer treatment and the psychosocial outcomes associated with anxious-withdrawal. Infant Child Dev. 2014, 23, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.F.; David, A.C. Teen-age companions work with disturbed children. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 1973, 24, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.; Smokowski, P. Prosocial bystander behavior in bullying dynamics: Assessing the impact of social capital. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 2289–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M.; Mennis, J.; Russell, M.; Moore, M.; Brown, A. Adolescent depression and substance use: The protective role of prosocial peer behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Liang, L.; Chen, W.; Bian, Y. Do gifts of roses have a lingering fragrance? Evidence from altruistic interventions into adolescents’ subjective well-being. J. Adolesc. 2021, 86, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago Perez, T.; Crowe, B.M. Community participation for transition-aged youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Ther. Recreat. J. 2021, 55, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Studsrød, I. “Help goes around in a circle”: Young unaccompanied refugees’ engagement in interpersonal relationships and its significance for resilience. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2019, 15, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, M.T. Social connectedness and self-esteem: Predictors of resilience in mental health among maltreated homeless youth. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 35, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, K.D.; Taylor, C.L.; Zubrick, S.R. Psychosocial resilience and vulnerability in western Australian aboriginal youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 78, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, Y.; Fujiwara, T.; Isumi, A.; Doi, S. Degree of influence in class modifies the association between social network diversity and well-being: Results from a large population-based study in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 260, 113170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanghøj, S.; Pappot, H.; Hjalgrim, L.L.; Hjerming, M.; Visler, C.L.; Boisen, K.A. Helping others: Reasons for participation in service user involvement initiatives from the perspective of adolescents and young adults with cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2019, 8, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.Y.S. From helper to partner: Processes of contact in voluntarism with refugees in Chinese youths. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2020, 48, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzel, K.R.; McNamara, C.C. Interpersonal relationships, emotional distress, and prosocial behavior in middle school. J. Early Adolesc. 1999, 19, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A.; Braverman, S.; Meirow, G. Video games and close relations: Attachment and empathy as predictors of children’s and adolescents’ video game social play and socio-emotional functioning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, S.M.; Cho, J.; Beach, S.R.H.; Smith, A.K.; Nishitani, S. Oxytocin receptor gene methylation and substance use problems among young African American men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 192, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Siu, A.M.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Cheng, H.; Tsang, S.; Lui, J.; Lung, D.; Shek, D.T.L.; Siu, A.M.H.; Lee, T.Y.; et al. Development and validation of a positive youth development scale in Hong Kong. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2006, 18, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.; Marley, M.; Torres, K.; Edelblute, A.; Novins, D. “Be creative and you will reach more people”: Youth’s experiences participating in an arts-based social action group aimed at mental health stigma reduction. Arts Health Int. J. Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 12, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Won, D.; Park, S. School engagement, self-esteem, and depression of adolescents: The role of sport participation and volunteering activity and gender differences. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidourek, R.A.; King, K.A. Parent, teacher, and school factors associated with over-the-counter drug use among multiracial youth. Am. J. Health Educ. 2013, 44, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoorn, J.; Van Dijk, E.; Crone, E.; Stockmann, L.; Rieffe, C. Peers influence prosocial behavior in adolescent males with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 2225–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollett, N.; Cluver, L.; Hatcher, A.M.; Brahmbhatt, H. “To be HIV positive is not the end of the world”: Resilience among perinatally infected HIV positive adolescents in Johannesburg. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 70, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.; Thompson, E.; Mehari, K. Dimensions of peer influences and their relationship to adolescents’ aggression, other problem behaviors and prosocial behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 1351–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uludağlı, N.P.; Sayıl, M. Problem and prosocial behaviors in offender adolescents: Links to adolescent, maternal and friend characteristics. Türk Psikol. Derg. 2013, 28, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, S.; McCleary, L.; Garcia, L.; Robitaille, A. Examining the benefits of intergenerational volunteering in long-term care: A review of the literature. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2017, 15, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalalinia, S.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Malekafzali, H.; Peykari, N. Peer education: Participatory qualitative educational needs assessment. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montañez, E.; Berger-Jenkins, E.; Rodriguez, J.; McCord, M.; Meyer, D. Turn 2 us: Outcomes of an urban elementary school-based mental health promotion and prevention program serving ethnic minority youths. Child. Sch. 2015, 37, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Bowes, L.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F. Protective factors interrupting the continuity from school bullying to later internalizing and externalizing problems: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. J. Sch. Violence 2014, 13, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, C.B.R.; Smokowski, P.R.; Rose, R.A.; Mercado, M.C.; Marshall, K.J. Cumulative bullying experiences, adolescent behavioral and mental health, and academic achievement: An integrative model of perpetration, victimization, and bystander behavior. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2415–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchment, T.M.; Jones, J.; Del-Villar, Z.; Small, L.; McKay, M. Integrating positive youth development and clinical care to enhance high school achievement for young people of color. J. Public Ment. Health 2016, 15, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, E.S.; Dulaney, C.L. Depressive symptoms and prosocial behavior after participation in a bullying prevention program. J. Sch. Violence 2006, 5, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, G.; Froh, J.J.; Bausert, S.; Disabato, D.; McKnight, P.; Blalock, D. Gratitude’s role in adolescent antisocial and prosocial behavior: A 4-year longitudinal investigation. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 14, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Carter, E.; Ivory, S.; Lin, L.C.; Muscatell, K.A.; Telzer, E.H. Role fulfillment mediates the association between daily family assistance and cortisol awakening response in adolescents. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, T.; Skouteris, H.; Townsend, M.; Hooley, M. The act of giving: A pilot and feasibility study of the my life story programme designed to foster positive mental health and well-being in adolescents and older adults. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 22, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, S.; Summers, J.J. Peer victimization and depressive symptoms in Mexican American middle school students: Including acculturation as a variable of interest. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2009, 31, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, P.J.; Hoyt, L.T.; Pachucki, M.C. Impacts of adolescent and young adult civic engagement on health and socioeconomic status in adulthood. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 1138–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.K.; Silbereisen, R.K. Participation in voluntary organizations and volunteer work as a compensation for the absence of work or partnership? Evidence from two German samples of younger and older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 67, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, K.; Bassi, M.; Junnarkar, M.; Negri, L. Mental health and psychosocial functioning in adolescence: An investigation among Indian students from Delhi. J. Adolesc. 2015, 39, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.K.; Gamble, W.C. Community service for youth: The value of psychological engagement over number of hours spent. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, K.; Tiiri, E.; Lempinen, L.; Sillanmäki, L.; Kronström, K.; Sourander, A. Time trends of Finnish adolescents’ mental health and use of alcohol and cigarettes from 1998 to 2014. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venta, A.; Bailey, C.; Muñoz, C.; Godinez, E.; Colin, Y.; Arreola, A.; Abate, A.; Camins, J.; Rivas, M.; Lawlace, S. Contribution of schools to mental health and resilience in recently immigrated youth. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydstedt, L.W.; Österberg, J. Psychological characteristics of Swedish mandatory enlisted soldiers volunteering and not volunteering for international missions: An exploratory study. Psychol. Rep. 2013, 112, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougeaux, E.; Hope, S.; Viner, R.M.; Deighton, J.; Law, C.; Pearce, A. Is mental health competence in childhood associated with health risk behaviors in adolescence? Findings from the UK millennium cohort study. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storch, E.A.; Masia-Warner, C. The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescent females. J. Adolesc. 2004, 27, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.E.; Wang, A.R.; Rowles, B.M.; Lee, M.T.; Johnson, B.R. Social anxiety and peer helping in adolescent addiction treatment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 39, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGinley, M.; Evans, A.M. Parent and/or peer attachment? Predicting emerging adults’ prosocial behaviors and internalizing symptomatology. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Lonigro, A.; Pallini, S.; Baiocco, R. Peer buddies in the classroom: The effects on spontaneous conversations in students with autism spectrum disorder. Child Youth Care Forum 2018, 47, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, P.; Matricardi, G.; Speltri, D.; Toso, D. The assessment of empathy in adolescence: A contribution to the Italian validation of the “basic empathy scale”. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balconi, M.; Canavesio, Y. Emotional contagion and trait empathy in prosocial behavior in young people: The contribution of autonomic (facial feedback) and balanced emotional empathy scale (BEES) measures. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2013, 35, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, P.; Maunders, K. The effectiveness of creative bibliotherapy for internalizing, externalizing, and prosocial behaviors in children: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 55, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.L.; Metz, A.E. Examining the meaning of training animals: A photovoice study with at-risk youth. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2014, 30, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, M.M. Associations between social potential and emotional and behavioral difficulties in Egyptian children. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2012, 17, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinkhani, Z.; Parsaeian, M.; Hassanabadi, H.-R.; Nedjat, S.; Khoshkchali, A.; Alinesaei, Z. Mental health problems in Iranian adolescents: Multilevel analysis...9th Iranian congress of epidemiology, October 22, 2019, Tehran, Iran. J. Saf. Promot. Inj. Prev. 2019, 7, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, L.J.; Jackson, D.; Woods, C.; Usher, K. Rewriting stories of trauma through peer-to-peer mentoring for and by at-risk young people. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gano-Overway, L.A.; Newton, M.; Magyar, T.M.; Fry, M.D.; Kim, M.S.; Guivernau, M.R. Influence of caring youth sport contexts on efficacy-related beliefs and social behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Di Giunta, L.; Panerai, L.; Eisenberg, N. The contribution of agreeableness and self-efficacy beliefs to prosociality. Eur. J. Pers. 2010, 24, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reeb, R.N.; Folger, S.F.; Langsner, S.; Ryan, C.; Crouse, J. Self-efficacy in service-learning community action research: Theory, research, and practice. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 46, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Martin, A.J.; Armstrong, D.; Walker, R. Risk, protection, and resilience in Chinese adolescents: A psycho-social study. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 14, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.J. The need to contribute during adolescence. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J.; Kim, M.-S.; Hwang, H.; Lee, B.-Y. Effects of intrinsic motivation and informative feedback in service-learning on the development of college students’ life purpose. J. Moral Educ. 2018, 47, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kim, E.S.; Koh, H.K.; Frazier, A.L.; VanderWeele, T.J. Sense of mission and subsequent health and well-being among young adults: An outcome-wide analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kulis, S.S.; Jager, J.; Ayers, S.L.; Lateef, H.; Kiehne, E. Substance use profiles of urban American Indian adolescents: A latent class analysis. Subst. Use Misuse 2016, 51, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, K.A.; Childs, J.C.; Sepples, S.B. Intervening with at-risk youth: Evaluation of the youth empowerment and support program. Pediatr. Nurs. 2003, 29, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kosterman, R.; Mason, W.A.; Haggerty, K.P.; Hawkins, J.D.; Spoth, R.; Redmond, C. Positive childhood experiences and positive adult functioning: Prosocial continuity and the role of adolescent substance use. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bullis, M.; Yovanoff, P. Idle Hands: Community employment experiences of formerly incarcerated youth. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2006, 14, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, E.A.; Fuligni, A.J. Self and others in adolescence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bibou-Nakou, I.; Markos, A.; Padeliadu, S.; Chatzilampou, P.; Ververidou, S. Multi-informant evaluation of students’ psychosocial status through sdq in a national Greek sample. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 96, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Brennan, R.T.; Rubin-Smith, J.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Gilman, S.E. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A longitudinal study of risk, protective factors and mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Rice, S.; Kelly, M.T.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S.; Broom, A.; Robertson, S.; Black, N. A mixed-methods study of the health-related masculine values among young Canadian men. Psychol. Men Masc. 2019, 20, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doré, B.P.; Morris, R.R.; Burr, D.A.; Picard, R.W.; Ochsner, K.N. Helping others regulate emotion predicts increased regulation of one’s own emotions and decreased symptoms of depression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macartney, G.; Stacey, D.; Harrison, M.B.; VanDenKerkhof, E. Symptoms, coping, and quality of life in pediatric brain tumor survivors: A qualitative study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proudfoot, J.; Fogarty, A.S.; McTigue, I.; Nathan, S.; Whittle, E.L.; Christensen, H.; Player, M.J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Wilhelm, K. Positive strategies men regularly use to prevent and manage depression: A national survey of Australian men. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, E.; Glemser, C.; Premoli, M.; Preti, E.; Richetin, J. The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies on the association between rejection sensitivity, aggression, withdrawal, and prosociality. Emotion 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memmott-Elison, M.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Yorgason, J.B.; Coyne, S.M. Intra-individual associations between intentional self-regulation and prosocial behavior during adolescence: Evidence for bidirectionality. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.A.; Dowdy, E.; Nylund-Gibson, K.; Furlong, M.J. An empirical approach to complete mental health classification in adolescents. Sch. Ment. Health Multidiscip. Res. Pract. J. 2019, 11, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callina, K.S.; Johnson, S.K.; Buckingham, M.H.; Lerner, R.M. Hope in context: Developmental profiles of trust, hopeful future expectations, and civic engagement across adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scales, P.C.; Benson, P.L.; Roehlkepartain, E.C. Adolescent thriving: The role of sparks, relationships, and empowerment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, H.; Youniss, J. School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2006, 10, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrow, F.H.; Armstrong, M.I.; Vargo, A.; Boothroyd, R.A. Understanding the findings of resilience-related research for fostering the development of African American adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 16, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholl, M.C.; Valenzuela, J.M.; Nierenberg, B.; Mayersohn, G.S. Diabetes camp counselors: An exploration of counselor characteristics and quality of life outcomes. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; Giles, M.; McLaughlin, M. Benefit finding and resilience in child caregivers. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, S.; Knight-Webb, G.; Breau, K. Volunteer adolescents in adolescent group therapy: Effects on patients and volunteers. Br. J. Psychiatry 1976, 129, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, J.C.; Sepples, S.B.; Moody, K.A. Educational innovations. Mentoring youth: A service-learning course within a college of nursing. J. Nurs. Educ. 2003, 42, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winsor, R.E.; Skovdal, M. Agency, Resilience and Coping: Exploring the psychosocial effects of goat ownership on orphaned and vulnerable children in Western Kenya. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 21, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ross, A.M.; Hart, L.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Kelly, C.M.; Kitchener, B.A. Development of key nessages for adolescents on providing basic mental health first aid to peers: A delphi consensus study. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2012, 6, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pătraș, L.; Martínez-Tur, V.; Gracia, E.; Moliner, C. Why do people spend money to help vulnerable people? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waldemar, J.O.C.; Rigatti, R.; Menezes, C.B.; Guimarães, G.; Falceto, O.; Heldt, E. Impact of a combined mindfulness and social–emotional learning program on fifth graders in a Brazilian public school setting. Psychol. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallott, M.A.; Maner, J.K.; DeWall, N.; Schmidt, N.B. Compensatory deficits following rejection: The role of social anxiety in disrupting affiliative behavior. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setterfield, M.; Walsh, M.; Frey, A.-L.; McCabe, C. Increased social anhedonia and reduced helping behavior in young people with high depressive symptomatology. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 205, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruchkin, V.; Sukhodolsky, D.G.; Vermeiren, R.; Koposov, R.A.; Schwab-Stone, M. Depressive symptoms and associated psychopathology in urban adolescents: A cross-cultural study of three countries. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006, 194, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Criss, M.M.; Ratliff, E.; Wu, Z.; Houltberg, B.J.; Silk, J.S.; Morris, A.S. Longitudinal links between maternal and peer emotion socialization and adolescent girls’ socioemotional adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerlemans, A.M.; Rommelse, N.N.J.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Hartman, C.A. Examining the intertwined development of prosocial skills and ASD Symptoms in adolescence. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kofler, M.J.; Larsen, R.; Sarver, D.E.; Tolan, P.H. Developmental trajectories of aggression, prosocial behavior, and social-cognitive problem solving in emerging adolescents with clinically elevated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015, 124, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, A.J.; Maughan, B.; Barker, E.D. Health and functional outcomes for shared and unique variances of interpersonal callousness and low prosocial behavior. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2019, 41, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Debchoudhury, I.; Welch, A.E.; Fairclough, M.A.; Cone, J.E.; Brackbill, R.M.; Stellman, S.D.; Farfel, M.R.; Debchoudhury, I.; Welch, A.E.; Fairclough, M.A.; et al. Comparison of health outcomes among afiliated and lay disaster volunteers enrolled in the world trade center health registry. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dew, M.A.; Butt, Z.; Liu, Q.; Simpson, M.A.; Zee, J.; Ladner, D.P.; Holtzman, S.; Smith, A.R.; Pomfret, E.A.; Merion, R.M.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of patient-reported long-term mental and physical health after donation in the adult-to-adult living-donor liver transplantation cohort study. Transplantation 2018, 102, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, R.R.; Johnson, S.M.; Exline, J.J.; Post, S.G.; Pagano, M.E. Addiction and “generation me”: Narcissistic and prosocial behaviors of adolescents with substance dependency disorder in comparison to normative adolescents. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2012, 30, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Attar-Schwartz, S.; Tan, J.-P.; Buchanan, A.; Flouri, E.; Griggs, J. Grandparenting and adolescent adjustment in two-parent biological, lone-parent, and step-families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mesurado, B.; Vidal, E.M.; Mestre, A.L. Negative emotions and behavior: The role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. J. Adolesc. 2018, 64, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, S.; Balottin, L.; Toldo, I.; Gatta, M. Alexithymia and psychosocial problems among Italian preadolescents. A latent class analysis approach. Scand. J. Psychol. 2016, 57, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Fine, S.L.; Brennan, R.T.; Betancourt, T.S. Coping and mental health putcomes among Sierra Leonean war-affected youth: Results from a longitudinal study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Lin, L.; Zhang, W. Latent profile analysis of left-behind adolescents’ psychosocial adaptation in Rural China. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, E.A. Considerations of fairness in the adolescent brain. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Syvertsen, A.K.; Flanagan, C.A. Developmental change in social responsibility during adolescence: An ecological perspective. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zong, M.; Yang, Z.; Gu, W.; Dong, D.; Qiao, Z. When altruists cannot help: The influence of altruism on the mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milledge, S.V.; Cortese, S.; Thompson, M.; McEwan, F.; Rolt, M.; Meyer, B.; Sonuga-Barke, E.; Eisenbarth, H. Peer relationships and prosocial behavior differences across disruptive behaviors. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, K.; Ryst, E.; Steiner, H. Adolescent defense style and life stressors. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 1999, 30, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, M.; Horváth, Z.; Morgan, A.; Kökönyei, G. Well-being profiles in adolescence: Psychometric properties and latent profile analysis of the mental health continuum model—A methodological study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, P.J.; Wood, A.M. Discrepancies in parental and self-appraisals of prosocial characteristics predict emotional problems in adolescents. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 52, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamut, S.T.; van den Berg, Y.H.M.; Lansu, T.A.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Bidirectional associations between popularity, popularity goal, and aggression, alcohol use and prosocial behaviors in adolescence: A 3-year prospective longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-P.; Burstein, M.; Schmitz, A.; Merikangas, K.R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (sdq): The factor structure and scale validation in US adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Carlo, G.; Nielson, M.G. Does helping keep teens protected? Longitudinal bidirectional relations between prosocial behavior and problem behavior. Child Dev. 2015, 86, 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]