Inter-Peer Group Status and School Bullying: The Case of Middle-School Students in Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Japanese Middle-School Context

1.2. “School Caste” (Inter-Peer-Group Status) and School Bullying

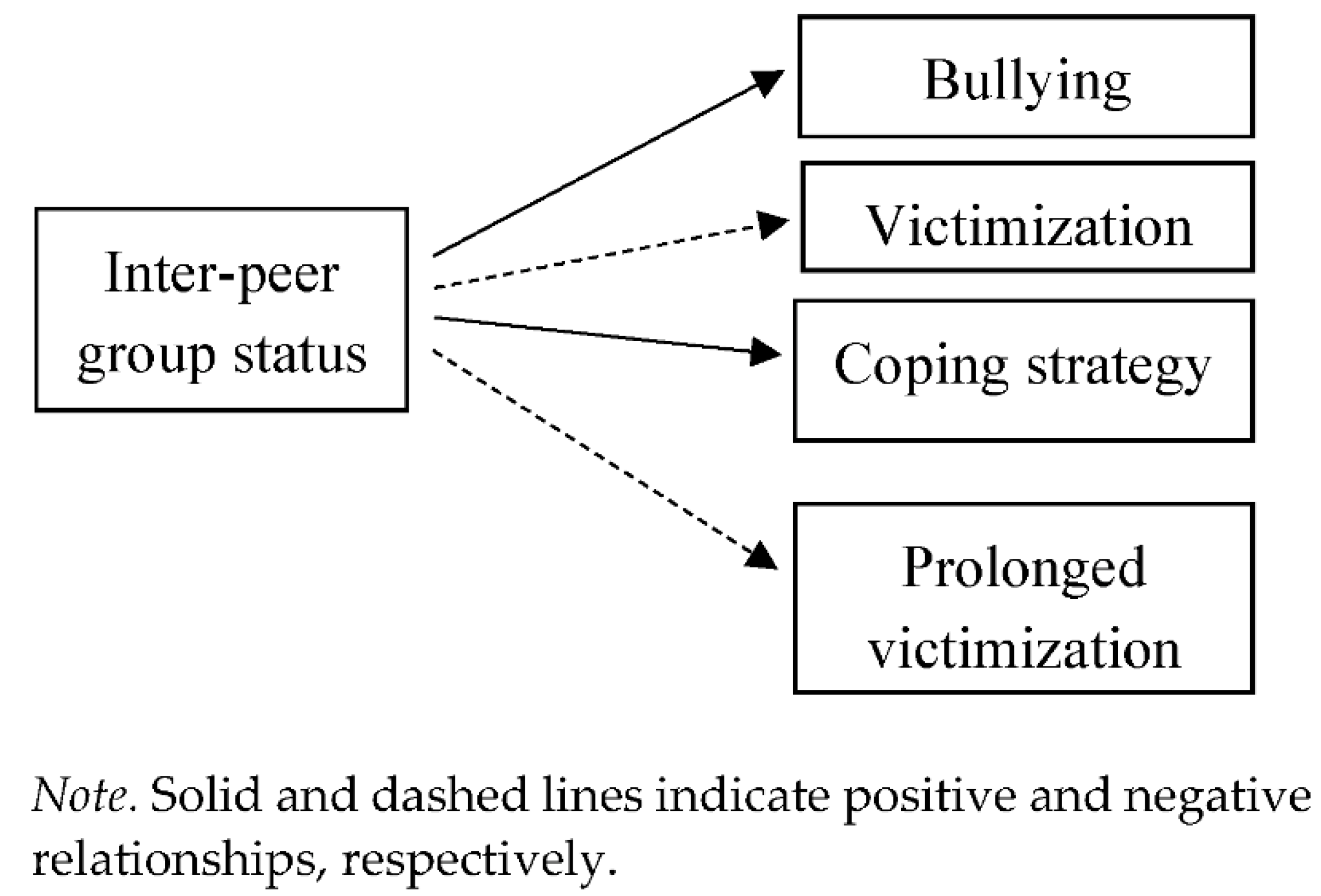

1.3. Overview of the Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Response Rates and Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Categorization of Participants into Subgroups of School Bullying

3.3. Inter-Peer Group Status and Sub-Categories of School Bullying

3.4. Inter-Peer Group Status and Coping Strategy

3.5. Inter-Peer Group Status and Current Victimization Status (never Resolved, Resolved, and Somewhat Resolved)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Peer-Group Status and School Bullying

4.3. Limitations of the Study

4.4. Implications of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van den Berg, Y.H.M.; Lansu, T.A.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Preference and popularity as distinct forms of status: A meta-analytic review of 20 years of research. J. Adolesc. 2020, 84, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstrom, M.J.; Cillessen, A.H. Likeable versus popular: Distinct implications for adolescent adjustment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2006, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravita, S.C.S.; DI Blasio, P.; Salmivalli, C. Early Adolescents’ Participation in Bullying: Is ToM Involved? J. Early Adolesc. 2009, 30, 138–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, J.L.; van Noorden, T.H.J.; Lansu, T.A.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. The participant roles of bullying in different grades: Prevalence and social status profiles. Soc. Dev. 2018, 27, 732–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caravita, S.C.S.; Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T. Main and Moderated Effects of Moral Cognition and Status on Bullying and Defending. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Broek, N.; Deutz, M.H.F.; Schoneveld, E.A.; Burk, W.J.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Behavioral correlates of prioritizing popularity in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 2444–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cillessen, A.H.N.; Schwartz, D.; Mayeux, L. (Eds.) Popularity in the Peer System; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen, A.H.N.; Mayeux, L. From Censure to Reinforcement: Developmental Changes in the Association Between Aggression and Social Status. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troop-Gordon, W.; Ranney, J.D. Popularity among same-sex and cross-sex peers: A process-oriented examination of links to aggressive behaviors and depressive affect. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1721–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, T.; Jin, S.; Li, L.; Niu, L.; Chen, X.; French, D.C. Longitudinal associations between popularity and aggression in Chinese middle and high school adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 2291–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouwels, J.L.; Salmivalli, C.; Saarento, S.; van den Berg, Y.H.M.; Lansu, T.A.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Predicting adolescents’ bullying participation from developmental trajectories of social status and behavior. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caravita, S.C.S.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Agentic or Communal? Associations between Interpersonal Goals, Popularity, and Bullying in Middle Childhood and Early Adolescence. Soc. Dev. 2011, 21, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.L.; Penn, S.; Nesdale, D.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. Popularity: Does it magnify associations between popularity prioritization and the bullying and defending behavior of early adolescent boys and girls? Soc. Dev. 2016, 26, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.-J.; Garandeau, C.F.; Rodkin, P.C. Effects of Classroom Embeddedness and Density on the Social Status of Aggressive and Victimized Children. J. Early Adolesc. 2010, 30, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, C.F.; Lansu, T.A.M. Why does decreased likeability not deter adolescent bullying perpetrators? Aggress. Behav. 2019, 45, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmivalli, C. Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2010, 15, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.; Tom, S.R.; Chang, L.; Xu, Y.; Duong, M.T.; Kelly, B.M. Popularity and Acceptance as Distinct Dimensions of Social Standing for Chinese Children in Hong Kong. Soc. Dev. 2009, 19, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.L.; Banny, A.M.; Kawabata, Y.; Crick, N.R.; Gau, S.S. A cross-lagged structural equation model of relational aggression, physical aggression, and peer status in a Chinese culture. Aggress. Behav. 2013, 39, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, H.; Shi, J. Chinese and American children’s perceptions of popularity determinants: Cultural differences and behavioral correlates. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2012, 36, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Li, L.; Niu, L.; Jin, S.; French, D.C. Relations between popularity and prosocial behavior in middle school and high school Chinese adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 42, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board of Education in Tokushima Prefecture (n.d.). Chinese Culture, Customs and Educational Circumstances. Guide for Accepting Children with Foreign Roots. Available online: http://jci-tws.com/f-children/country-china.html#wrapper (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Kanetsuna, T. Comparisons between English bullying and Japanese ijime. In School Bullying in Different Cultures: Eastern and Western Perspectives; Smith, P.K., Kwak, K., Toda, Y., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, Y. The Nature of School Caste; Shogakukan: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi, A. The Structure of ‘Ijime’; Kodansya: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, K.; Ota, M. Relationships between school caste and school adjustment among junior high school students. Jpn. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 65, 501–511, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mizuno, K.; Hidaka, M. What Kinds of Classroom Environments Affect Relations Between Inter-Peer-Group Status and Subjective School Adjustment? Jpn. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 67, 1–11, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, S. School Caste; Kobunsya: Tokyo, Japan, 2012. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, K.; Kato, H.; Ota, M. An investigation into the relationships between inter-peer group status and victimization/bullying among Japanese middle school students. Jpn. J. Interpers. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 19, 14–21, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Berger, C.; Caravita, S.C. Why do early adolescents bully? Exploring the influence of prestige norms on social and psychological motives to bully. J. Adolesc. 2015, 46, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Gamez-Guadix, M. Do extraversion and neuroticism moderate the association between bullying victimization and internalizing symptoms? A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, M.E.; Olweus, D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggress. Behav. 2003, 29, 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, M.E.; Olweus, D.; Endresen, I.M. Bullies and victims at school: Are they the same pupils? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, A.; Lee, K.; Wolke, D. Comparisons Between Adolescent Bullies, Victims, and Bully-Victims on Perceived Popularity, Social Impact, and Social Preference. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Bruyn, E.H.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; Wissink, I.B. Associations of peer acceptance and perceived popularity with bullying and victimization in early adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 2010, 30, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K. Understanding School Bullying: Its Nature and Prevention Strategies; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Ijime Boshi Taisaku Suishinho [Act for the Promotion of Measures to Prevent Bullying]. 2013. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/seitoshidou/1337278.htm (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Kato, H.; Ota, M.; Mizuno, K. Field survey of school bullying and help-seeking behavior among victims of school bullying: A comparison of mainstream and special needs education classrooms. Annu. Rep. Res. Clin. Cent. Child Dev. 2016, 8, 1–12. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Murayama, Y.; Ito, H.; Hamada, M.; Nakajima, S.; Noda, W.; Katagiri, M.; Takayanagi, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Tsujii, M. The relationships between bullying behaviors and the victimization of peers with internalizing/externalizing problems. Jpn. J. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 26, 13–22, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H. An introduction to the statistical free software HAD: Suggestions to improve teaching, learning and practice data analysis. J. Media Inf. Commun. 2016, 1, 59–73. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Williams, F.; Cornell, D.G. Student willingness to seek help for threats of violence in middle school. J. Sch. Violence 2006, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, S.; Peterson, E.R.; Stuart, J.; Utter, J.; Bullen, P.; Fleming, T.; Ameratunga, S.; Clark, T.; Milfont, T.L. Bystander Intervention, Bullying, and Victimization: A Multilevel Analysis of New Zealand High Schools. J. Sch. Violence 2014, 14, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, K.; Tang, Y. A review of “school caste” and its relation to peer relationships. Jpn. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 62, 311–327, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Never | Only Once | Once a Month | Once a Week | A Few Times a Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excluded or ignored | 89.1% | 7.4% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 0.7% |

| Had one’s belongings hidden or stolen | 91.0% | 5.9% | 1.9% | 0.7% | 0.4% |

| Talked about behind one’s back | 73.4% | 12.5% | 7.2% | 4.4% | 2.5% |

| Kicked or punched | 91.2% | 4.9% | 1.9% | 1.1% | 1.0% |

| Called names | 90.4% | 4.5% | 2.3% | 1.6% | 1.2% |

| Harassed on cyberspace | 98.3% | 1.2% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Attacked jokingly | 88.9% | 5.5% | 2.5% | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Sexually harassed | 98.9% | 0.7% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Exclude or ignore | 82.9% | 8.3% | 2.8% | 3.3% | 2.7% |

| Hide or steal someone’s belongings | 84.4% | 7.2% | 3.2% | 2.8% | 2.4% |

| Talk about someone behind their back | 69.5% | 10.3% | 6.4% | 6.3% | 7.4% |

| Kick or punch | 88.1% | 4.4% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.4% |

| Call someone names | 85.3% | 4.5% | 3.1% | 2.9% | 4.2% |

| Harass on cyberspace | 93.9% | 3.2% | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.7% |

| Attack jokingly | 85.7% | 5.2% | 3.3% | 2.2% | 3.6% |

| Sexually harass | 96.3% | 1.9% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.7% |

| Reference: Uninvolved | Bully Only | Victim Only | Bully–Victim | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Sex a | 1.03 | 0.73 | 1.43 | 0.60 *** | 0.43 | 0.84 | 0.42 *** | 0.26 | 0.66 |

| Grade a | 0.98 | 0.72 | 1.35 | 0.66 ** | 0.54 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 1.13 |

| Intra-peer group status a | 0.94 | 0.7 | 1.25 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 1.37 |

| Inter-peer group status | 1.02 | 0.78 | 1.34 | 0.77 * | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.69 | 1.19 |

| Asking Perpetrator to Stop Bullying | Fighting Back | Seeking Help from Parents | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Sex a | 0.61 | 0.34 | 1.09 | 0.33 ** | 0.17 | 0.66 | 3.72 *** | 1.94 | 7.13 |

| Grade a | 0.71 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.49 * | 1.03 | 2.15 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 1.27 |

| Intra-peer group status a | 0.90 | 0.70 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.76 | 1.45 | 0.75 | 0.53 | 1.07 |

| Inter-peer group status | 1.07 | 0.82 | 1.39 | 1.23 | 0.92 | 1.66 | 1.13 | 0.83 | 1.55 |

| Seeking help from teachers | Seeking help from friends | Doing nothing | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Sex a | 1.63 | 0.81 | 3.27 | 3.56 *** | 2.08 | 6.10 | 0.82 | 0.51 | 1.33 |

| Grade a | 0.82 | 0.60 | 1.13 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 0.88 | 1.59 |

| Intra-peer group status a | 1.01 | 0.68 | 1.50 | 1.05 | 0.75 | 1.46 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 1.27 |

| Inter-peer group status | 0.86 | 0.59 | 1.26 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.32 |

| Reference: Never Resolved | Resolved | Somewhat Resolved | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Sex a | 0.30 *** | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.43 ** | 0.15 | 1.81 |

| Grade a | 1.84 ** | 0.15 | 0.61 | 1.27 | 0.25 | 0.76 |

| Intra-peer group status a | 1.24 | 1.00 | 1.89 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 1.62 |

| Inter-peer group status | 1.38 * | 1.18 | 2.86 | 1.19 | 0.89 | 1.81 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mizuno, K.; Shu, Y.; Ota, M.; Kato, H. Inter-Peer Group Status and School Bullying: The Case of Middle-School Students in Japan. Adolescents 2022, 2, 252-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020020

Mizuno K, Shu Y, Ota M, Kato H. Inter-Peer Group Status and School Bullying: The Case of Middle-School Students in Japan. Adolescents. 2022; 2(2):252-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMizuno, Kumpei, Yue Shu, Masayoshi Ota, and Hiromichi Kato. 2022. "Inter-Peer Group Status and School Bullying: The Case of Middle-School Students in Japan" Adolescents 2, no. 2: 252-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020020

APA StyleMizuno, K., Shu, Y., Ota, M., & Kato, H. (2022). Inter-Peer Group Status and School Bullying: The Case of Middle-School Students in Japan. Adolescents, 2(2), 252-262. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020020