Abstract

Scoliosis is an abnormal curvature of the spine, which generally develops during childhood or adolescence. It affects 2–4 percent of the global population and is more prevalent among girls. Scoliosis is classified by its etiology: idiopathic, congenital, or neuromuscular. Among these, the former is the most common. Treatment options for scoliosis vary depending on the severity of the curve. Most scoliosis diagnoses tend to be mild and only require monitoring. However, curves between 20 and 40 degrees require bracing, while 40 degrees and above require surgery. There are various bracings available, such as Boston, Charleston, and Milwaukee. In severe cases of scoliosis, either fusion or fusionless surgery may be required. This review aims to discuss etiologies and different treatment interventions for scoliosis.

1. Introduction

Scoliosis is diagnosed when a spinal deformity exceeds a curve of 10 degrees []. This disease is most often identified at an early age, typically at 10 to 16 years []. Although scoliosis mostly affects children and carries on through adulthood, cases of adults developing this disease do occur. Fortunately, most cases of scoliosis tend to be mild. However, some experience worsening of the curve during puberty [].

Although the exact cause is often unknown, scoliosis is generally classified depending on its etiology: idiopathic, congenital, or neuromuscular []. Idiopathic scoliosis can further be subdivided according to the age of onset as infantile (age 0–3), juvenile (age 4–9), or adolescent (age 10 up to skeletal maturity) [,]. Congenital scoliosis is due to embryological malformation; thus children are typically diagnosed at a very early age []. Neuromuscular scoliosis is associated with secondary factors such as spinal cord trauma, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, or muscular dystrophy and can occur later in life []. Among these three groups, idiopathic scoliosis tends to be the most prevalent worldwide [] with approximately 2–4% of children between 10 and 16 years of age being diagnosed [].

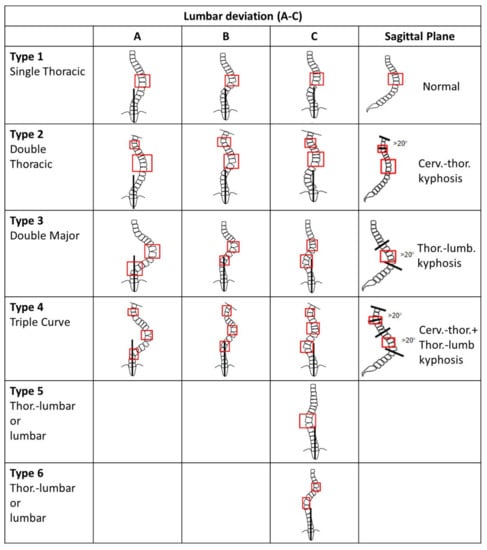

The curve itself was initially classified into five types under the King and Moe criteria []; however, in 2001 a new six-type classification system was developed by Lawrence Lenke (Figure 1) []. In Type 1, there is a main thoracic (MT) curve as the only structural curve while proximal and thoracolumbar are nonstructural. Type 2 is a double thoracic MT major curvature, while proximal thoracic (PT) is minor and structural, and thoracolumbar (TL) is minor and nonstructural. Type 3 has a double major curve pattern in the MT with lumbar as minor and structural, while PT is nonstructural. Type 4 has a triple major curve pattern in the MT with all three curves being structural. Type 5 has either a thoracolumbar or lumbar major curve, while PT and MT are minor and nonstructural. Finally, Type 6 has thoracolumbar or lumbar as the major curve measuring at least 5 degrees more than the MT curve, which is minor but structural. Lenke’s Types 1 and 5 are typically treated via either anterior or posterior methods, while Types 2, 3, 4, and 6 can be treated completely via the posterior method [].

Figure 1.

Lenke classification for spinal curvature. Modified from []. Generally, Type A has the CSVL between the pedicles to the lumbar apex. Type B has the CSVL touching the apical bodies to the lumbar apex. Type C has the CSVL completely medial to the apical lumbar vertebrae.

Initially, scoliosis is screened for via physical examination but only fully diagnosed by either CT scan, MRI, or X-ray []. Based on the degree angle, the severity of scoliosis is determined. Curves of 10 degrees or less are considered mild, between 10 and 50, moderate, while above 50 degrees is severe []. Curves under 20 degrees usually only require monitoring and thus no therapeutic intervention. Curves between 20 and 40° tend to require some form of bracing [,]. Severe scoliosis often requires surgery, typically spinal fusion []. Some risk factors for developing scoliosis include gender, age, ethnicity, and family history []. The ethnic disparity in scoliosis suggests that adolescents of African descent are more likely to be diagnosed than either European or Latin American individuals, in addition to also being more likely to suffer from complications [].

Psychosocial factors are additional concerns for children since treatment often involves wearing a bulky brace on a daily basis. This can cause stress while in school or when trying to perform physical activities []. Young adolescents, as well as their peers and parents, often visualize scoliosis as a body disfigurement, which can lead to negative body image perceptions. This dissatisfaction with appearance can often lead to decreased self-esteem, anxiety, and even depression []. Herein is an overview of factors that can contribute to developing scoliosis, in addition to a brief overview of various treatment options.

2. Causes

There is controversy regarding the causes of scoliosis, whether it is solely genetic or has specific contributing factors, such as exercising and the environment. According to a study done by Zhuang et al., it was concluded that patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) had an alteration in five bone growth-related proteins, specifically pyruvate kinase M2, annexin A2, heat shock 27 k protein, γ-actin, and β-actin []. In addition, from linkage analysis, mutations in the gene loci of MAPK7 and allele marker DS 1034 on chromosome 19p13.3 were shown to contribute to AIS [].

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) which analyzed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and phenotypes, as well as copy number variants (CNV), specifically looked at AIS. Ogura et al., found that ladybird homeobox 1 (LBX1) and CNV of chromosomes 1q21.1, 2q13, 15q11.2, and 16p11.2harbor were associated with AIS []. Additionally, Mao et al., evaluated DNA methylation levels and observed an inverse relationship between cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) promotor and expression of the COMP gene. Over-methylation led to a lower expression of this gene, which itself is responsible for bone formation. The positive methylation of the pituitary homeobox 1 gene of its promotor region led to larger curve angles of the spine []. Raggio suggested that the autosomal recessive chromosome, 12p.13.3 heavily influences AIS []. Likewise, Chan reported that chromosome p13.3, among Asian children, is a key factor for AIS development []. A few other chromosomal influencers have also been identified (Table 1) [].

Table 1.

Summary of current genetic linkage studies for AIS. Modified from [].

In addition, there have been multiple findings linking scoliosis with genetic inheritance. A study conducted in 1968 by Wynne-Davies evaluated the familial incidence rate of AIS. The first, second, and third generational inheritance was 6.9, 3.7, and 1.6%, respectively [].

Although debatable, research has explored the effect of hormones on the development of AIS. Pinchuk suggested that disturbance in biorhythm secretion plays a role in the development of scoliosis []. Additionally, melatonin receptor 1B (MT2) expression in osteoblast cells in patients with AIS was observed at a lower level compared to those without scoliosis []. Similarly, a lack of estrogen has been linked to deficits in bone maturation which can further lead to the potential development of AIS [].

Gender is strongly linked with scoliosis prevalence, with much higher rates among females. Remarkably, the ratio of spinal curves of 30 degrees or higher between females to males is 10:1 [,]. A region on the X-chromosome, which plays a role in scoliosis, has recently been identified. In 2003, Justice et al., analyzed 15 markers for X chromosomes in 202 families. It was concluded that regions Xq23 and Xq26.1 significantly contribute to the higher prevalence of AIS among females [].

Although the exact causative relationship between exercising and scoliosis remains unclear, specific research was conducted to assess this []. Male and female athletes between the ages of 12 and 15 were evaluated. Accordingly, the prevalence of AIS was 2–3 fold higher among athletic versus non-athletic adolescents. It was found that among various exercises, early introduction of swimming had the greatest association with developing AIS, while dancing, skating, horseback riding, gymnastics, and karate were less so. The study concluded that there were no additional statistically significant data related to age, height, weight, or BMI influencing the prevalence of AIS among adolescent athletes [].

In addition to exercising, other secondary factors have been investigated as possibly contributing to scoliosis. These are grouped into three categories: inherited disorders of connective tissue, neurologic disorders, and musculoskeletal disorders []. Neuromuscular etiologies, such as cerebral palsy, spinal amyotrophy, or myelodysplasia are all neurologic disorders that in themselves can lead to scoliosis []. Other examples of specific disease states related to secondary causes of scoliosis are listed in Table 2 [].

Table 2.

Secondary factors leading to scoliosis. Modified from [].

There has also been some linkage of vertebral malformations with the consumption of alcohol, maternal insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and anticonvulsant medications, such as valproic acid and dilantin during fetal development []. Although there have been no direct studies assessing the causative relationship of environmental teratogens with vertebral malformations, similar studies performed on animals suggest that there may indeed be some influence []. Yang et al., observed that a high-selenium concentration can induce S-curve deformity in guppy fish []. Likewise, McMaster et al., suggested that chloroform generated in heated swimming pools can contribute to scoliosis via a neurotoxic effect []. There is approximately a three times higher rate of developing infant and normal adolescents’ scoliosis among children who regularly use heated indoor swimming pools [,]. These findings may explain the aforementioned disparity among adolescent swimmer athletes []. Further testing still needs to be done to confirm any additional association between environmental factors and scoliosis.

3. Kinesitherapy

The first treatment for scoliosis dates back to the 5th century BC when it was described by Hippocrates as longitudinal traction. This was a painful and crude treatment utilizing a scamnum (similar to a torture rack) and continued until the 2nd century AD []. The first torso brace was developed by Ambrose Pare, a French army surgeon in the 16th century. He hypothesized that spinal deformity was due to the dislocation of the spine. Pare designed a padded iron corset for patients to reduce the progression of the curve [,]. Subsequently, additional treatment methods were developed, and in 1946 the Milwaukee brace was introduced, becoming a leading option for treating scoliosis [].

Presently, there are various braces, and other additional treatment options, such as acupuncture. Besides bracing and surgery, which will be discussed below, other approaches have also been evaluated, such as acupuncture [,,]. From a case report, where acupuncture was performed 3 times a week for 6 weeks, a correction in the curvature was reported at 10 degrees []. In another study, 24 AIS patients, between the age of 14 and 16 received acupuncture treatment lasting approximately 25 min. It was concluded that AIS patients with curvature below 35 degrees benefited []. However, more research and follow-up investigation are necessary to validate this treatment option.

Bracing is the most widely studied and utilized approach for scoliosis treatment. Although there is very limited research to directly compare the effectiveness of these braces to each other, certain ones are preferred for a variety of reasons. For bracing to be successful, the spinal curve should remain under 45 degrees until the patient reaches full maturity []. Walter Blount’s specific advancement was to introduce removable cervicothoracolumbosacral orthosis (CTLSO) pads. This Milwaukee brace uses both passive and active forces to assist in spinal straightening. Passive correction is accomplished from pressure by the CTLSO pads. The original chin rest of the Milwaukee brace was ultimately changed to a throat pad because its pressure led to orthognathic deformities. In addition, the custom-molded leather from the patient’s cast was modified to prefabricated thermoplastics as it was easier to use and less expensive. However, compliance with wearing was and is one of the major issues associated with this brace. Many patients complain about its appearance as well as general discomfort. Despite these limitations, the Milwaukee brace has been used for 75 years and has been shown to assist in halting the progression of AIS [].

The Milwaukee brace is often used to treat thoracic curves with an apex at or above T8 []. Misterska et al., performed a study to evaluate the efficacy of the Milwaukee brace []. A total of 30 female patients who completed treatment with Milwaukee brace before they reached 19 years old were evaluated. The success rate was defined as an increase in the spinal curve of fewer than 6 degrees since the start of bracing []. The Milwaukee brace led to curves between 20 and 29 degrees progressing 28% less compared to when left untreated, and curves between 30 and 39 degrees progressed 14% less [].

In 1969, G. Dean MacEwen created a low-profile thoracic lumbar spinal orthosis (TLSO) brace which was lighter, more comfortable, and less obtrusive for patients. The first TLSO brace was coined the Wilmington brace. It was constructed as semi-rigid from moldable plastic. Due to the challenges of custom-molding these braces, John Hall and William Miller created another TLSO referred to as the Boston brace in 1972. Instead of custom-fitting each patient, prefabricated braces were custom-modified. Similar to the Milwaukee brace, Boston braces also used passive and active corrective forces [].

The Boston brace has shown to be most effective in scoliosis at an apex between T6 and L4, with curves from 20 to 49 degrees []. It is not generally as useful when curves are located above T6 []. Steen et al., examined patients treated with the Boston brace to evaluate its efficacy []. A total of 365 patients with AIS participated in the study, of which 339 were female and 26 were male. The effectiveness of bracing decreased when worn less than 17 h daily. After brace weaning, follow-up was performed at 6, 12, and 25 months as well as long-term. Most participants attended one or more sessions. A success rate was seen in 300 of 365 patients (82%), while treatment failure was observed in 65 patients, with 27 (7%) requiring surgery. Treatment failure was defined as curve progression to greater than 50 degrees. Patients with poor compliance had an average of 6.9 degrees larger progression [].

Both Milwaukee and TLSO braces require patients to wear them for 18 to 23 h per day to be most effective. To increase patient compliance, nighttime bracing was introduced in 1979 by Frederick Reed []. This Charleston brace was intended to be worn only during sleeping hours. However, due to its rigid plastic mold and discomfort, compliance was often compromised. In 1992, Charles d’Amato and Barry McCoy developed an alternate brace to correct spinal curves with minimal discomfort. Unlike the Charleston brace which utilizes side-bending, this Providence brace directly applies forces in both a lateral and derotational manner. Both the Charleston and Providence braces are only used at nighttime [].

The Charleston brace is employed in patients with a single major curve of 25–35 degrees at an apex below T8 and is only worn for 8–10 h during sleep []. Nighttime bracing has been suggested to be more effective in those who have a single, correctable thoracolumbar, or lumbar curve []. A study performed by Wiemann evaluated the efficacy of the Charleston brace by enrolling 21 patients and 16 control group females []. All participants were followed up for a minimum of 2 years. In the control group, eight patients had between 5 and 10 degrees of curve progression, while the remaining eight had greater than 10 degrees. Among the treatment group, 6 patients (29%) maintained without progression of the curve, 4 patients (19%) progressed between 5 and 10 degrees, while 11 patients (52%) had greater than 10 degrees change. Additionally, two in the control and four in the bracing groups ended up requiring surgical intervention [].

A study was performed to compare the effectiveness of the Milwaukee, TLSO, and the Charleston braces when treating AIS []. A total of 170 patients aged 10–13 years, without a history of spinal surgery were eligible for the study. Of those patients, 30 used the Milwaukee brace (18%), 45 used a TLSO (26%), and 95 used the Charleston brace (56%). For scoliosis at the thoracic or double curve, as is often found in Type 2 and 3 cases, the Milwaukee brace is mainly utilized [,]. A TLSO, such as the Boston brace, is typically used for single lumbar and thoracolumbar curves with apexes at T8 or below [,]. Thus, a direct comparison of these braces may not be applicable as the curves are at different sites. Additionally, since the Milwaukee brace is mostly used for double curves, a comparision with a TLSO or Charleston brace may not be valid []. However, initial spinal correction showed better outcomes when treated with a TLSO than the Milwaukee brace. Long-term use of a TLSO brace minimized the progression of the curve. Additionally, patients who were treated with TLSOs had the lowest rate of surgery. Surgical rates after treatment with a brace were highest for those using Charleston. Ultimately, 8 of 45 patients with TLSO, 7 of 35 with Milwaukee, and 29 of 95 with the Charleston required surgical correction. However, the study had a limitation as it did not provide a follow-up and only examined patients who were at the end of brace treatment [].

Another study performed by Katz et al., compared Boston and Charleston braces []. The eligible AIS patients included those 10–17 years old with curves between 25 and 45 degrees. Of the 268 patients, 127 used a Boston brace and 141 used the Charleston. Among these, 243 were females (117 Boston and 126 Charleston) and 25 were males (10 Boston and 15 Charleston). Ultimately, the Boston brace was deemed more effective in preventing progression when starting curves were between 25 and 35 degrees. Only 29 of 99 patients (29%) treated with the Boston brace showed curve progression greater than 5 degrees, while 56 of 120 (47%) were seen with the Charleston brace. In addition, the Boston brace was more effective in preventing progression in curves with starting points between 36 and 45 degrees. A total of 23 of the 54 patients (43%) with curves between 36 and 45 degrees who were treated with the Boston brace had progression of more than 5 degrees while 38 of 46 (83%) were seen in the Charleston brace group []. However, a comparison is again difficult due to each brace being used for different spinal curve locations. Howard et al., analyzed a recently published retrospective meta-analysis, which compared improvements in patients who wore a brace for approximately 23 h a day []. Data was collected during the bracing period and followed up to evaluate which brace had better overall success rates between the TLSOs, Charleston, and Milwaukee. It was concluded that TLSOs significantly lowered the progression of the curve and thus had the highest overall brace success rate compared to other braces []. However, due to several limitations, such as the small sample size for follow-up and being used at different sites, no brace could be concluded as being superior to another []. Other braces have been developed such as the aforementioned Providence, Flexpine, Lyon, Chêneau, Spine-Cor, and ScolioSMART, but fewer clinical studies have been conducted on these, making it difficult to compare bracing treatments.

The Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) identifies the Cobb angle as a primary outcome that is most used to determine the success and effectiveness of orthosis treatment. A Cobb angle of 5° or less at the end of treatment or at the time of brace discontinuation is considered a successful and effective orthosis. Although comparisons have been done with different braces, the studies themselves are performed by different groups. Therefore each study has its own set of inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may differ significantly. Thus it is difficult to exactly compare and contrast the different braces. Additionally, individual researchers define success and failure in terms of brace effectiveness differently. Some studies include compliance and include maturity as a variable in their studies. Thus, a uniformity across studies is difficult to compare. Although there have been specific comparison studies on orthosis treatment for scoliosis, to fully compare and assess the efficacy of each orthosis, specific criteria need to also be included. Factors such as the initiation of the bracing period, curve magnitude at the initiation of therapy, and years of skeletal maturity differ across these studies. Ideally, there should be more stringent patient characteristics or inclusion criteria among studies to make a true comparison. Additionally, patients who were categorized as being “successful” should be followed up for a minimum of 2 years after skeletal maturity. Likewise, studies should include patient compliance to decrease bias, even if the report may be subjective (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Outcomes and conclusion from different bracing. Modified from [].

Table 4.

Limitations, length follow-up, and biases of brace studies.

4. Surgical Treatments

After diagnosis, curve progression of scoliosis approximately occurs at 1 degree annually []. The general goal of bracing is to maintain the curve below 50 degrees upon patient maturation. Although effective, bracing tends to prevent curves from worsening rather than permanently correcting or improving []. The rate of surgery after bracing is between 11 and 42.5%, depending on the previous treatment methods employed []. If treatment was rather conservative, there is a greater chance of surgery []. Surgical options are considered when a curve exceeds 45 degrees in immature patients and 50 degrees in mature. The goal of surgery is to halt the progression and improve spinal curvature and balance []. Surgical management of scoliosis is generally divided into fusion and fusionless []. In order to allow chest and lung development, spinal fusion is usually reserved until the patient is 10–12 years old or older. The fusion can be conducted either anteriorly or posteriorly, depending on the patient’s characteristics []. However, the posterior approach is more commonly used [,].

Posterior fusion surgery had been the mainstay of surgical treatment since it was first introduced by Paul Harrington in the 1950s. This involves the implantation of a Harrington rod along the spine to straighten the curve. Less implant failure, as well as better corrections, have been accomplished with more recent technology advancements. The modern posterior instrumentation has stronger anchorage support between the rod and spine. Presently, segmental pedicle screws or a hybrid construct using pedicle screws are commonly utilized in posterior surgery. In 1994, Suk was the first to introduce the segmental pedicle screw []. The safety of the segmental pedicle screw was evaluated with 203 thoracic AIS patients []. Among those, 170 patients had single thoracic and 33 had double thoracic curves. The patients were categorized under the older King 5-type classification. In total 122 patients were Type 2, 29 were Type 3, 19 were Type 4, and 33 were Type 5. Approximately 14 thoracic screws are inserted per patient. The two main goals of the study were to correct the spinal deformity and maintain stability []. According to the 5-year follow-up, the average correction was from 16 degrees to 51 degrees []. When evaluated in its totality, 2867 thoracic pedicle screws were used. However, 43 screws were found to be misplaced in 24 patients, which was confirmed by either CT or plain radiography. Of these, 12 screws were misplaced in lateral, 3 in medial, 8 in superior, and 20 in inferior regions. Regardless of malpositioning, follow-up showed no neurological or vascular adverse effects [].

Another fusion surgical method is anterior instrumentation. This method is preferred for thoracolumbar and lumbar scoliosis due to its superior correction at shorter fusion levels []. A combination of anterior and posterior fusion was generally preferred in severe and rigid curvatures []. However, utilization of anterior instrumentation has recently been decreasing due to the possibility of screw penetration, which can lead to a risk of thoracic aorta as well as having longer surgery and anesthesia times [,]. In 2005, Potter compared anterior and posterior spinal fusion []. The result showed that posterior instrumentation had better outcomes compared to anterior. The main thoracic posterior method showed 62% correction, while the anterior showed 52%. Additionally, thoracolumbar and lumbar had 56% correction with posterior, while only 41% with the anterior method [].

Fusionless surgery is generally performed due to several reasons, such as to control growth, delay the timing of fusion surgery, or increase the volume of the thorax. Because mobility and flexibility of the spine are removed with fusion surgery, use on immature children is often avoided (Table 5). This is even more so if the child has a spinal cord injury or myelodysplasia. In addition, performing fusion surgery when too young can also result in a shorter trunk compared to extremities, which can also influence the development of the lungs. Fusionless surgery is often preferred in AIS patients with a right thoracic curve. When 20 patients with right thoracic curves were treated with fusionless surgery and followed for an average of 8.9 years, no neurological complications were found []. Ultimately, 4 patients had a 9.8% correction rate after fusionless surgery (74.8 degrees to 67.5 degrees), while 16 patients had a 29.4% correction (61.3 degrees to 43.3 degrees) [].

Table 5.

Outcomes and comparison of different spinal fusion in scoliosis. Modified from [].

5. Conclusions

The goal of bracing therapy for scoliosis is to halt the progression of the curve to under 50 degrees until maturity. There are a number of braces available, such as Charleston, Boston, and Milwaukee, which are used depending on the patient’s curve characteristics. However, because bracing often does not stop the progression completely, surgical methods are a consideration in certain instances. Either fusion or fusionless approaches are utilized for surgical intervention. There are numerous studies done to evaluate the safety and efficacy of surgical treatment for scoliosis. Additionally, not enough clinical studies are available, making it impossible to compare different braces. Even with current studies analyzing and comparing various braces, there are limitations, such as limited follow-up and different treatment locations of the curve. Thus, a true comparison of one brace to another is not possible. Regardless, treatment for those diagnosed has come a long way from the days of the scamnum rack. As the technology continues to advance, spinal fusion may be more tolerable for patients. Conversely, with improvements in bracing in conjunction with physical therapy, there may be less need for surgery at all or perhaps less invasive surgeries. Finally, with advancements in pharmacogenomic testing, there is a possibility to understand AIS variants to allow for even earlier detection. Although neither bracing nor surgery cure scoliosis, genetic testing to determine those children at higher risk of AIS may open the possibility of preventing its development early with nutritional and physical therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.L. and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.B.L. and D.T.P.; writing—review and editing, G.B.L., D.T.P. and R.P.; supervision, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

None of the authors have received funding from any company, institution, foundation, grant, etc., related to the work described within the text. There are no conflicts of interest with any of the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the School of Pharmacy at the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences University for financial support of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yaman, O.; Dalbayrak, S. Idiopathic scoliosis. Turk. Neurosurg. 2014, 24, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reamy, B.V.; Slakey, J.B. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Review and current concepts. Am. Fam. Phys. 2001, 64, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Shakil, H.; Iqbal, Z.A.; Al-Ghadir, A.H. Scoliosis: Review of types of curves, etiological theories and conservative treatment. J. Back. Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2014, 27, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vialle, R.; Thévenin-Lemoine, C.; Mary, P. Neuromuscular scoliosis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2013, 99 (Suppl. S1), S124–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicki, J.A.; Alman, B. Scoliosis: Review of diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 12, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, D. Classification of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). J. Child. Orthop. 2013, 7, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemann, J.M.; Shah, S.A.; Price, C.T. Nighttime bracing versus observation for early adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2014, 34, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivas, T.B.; Vasiliadis, E.; Mouzakis, V.; Mihas, C.; Koufopoulos, G. Association between adolescent idiopathic scoliosis prevalence and age at menarche in different geographic latitudes. Scoliosis 2006, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieger, T.; Campo, S.; Weinstein, S.L.; Dolan, L.A.; Ashida, S.; Steuber, K.R. Body Image and Quality of Life and Brace Wear Adherence in Females With Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2017, 37, e519–e523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, A.; Farì, G.; Maccagnano, G.; Riondino, A.; Covelli, I.; Bianchi, F.P.; Tafuri, S.; Piazzolla, A.; Moretti, B. Teenagers’ perceptions of their scoliotic curves. An observational study of comparison between sports people and non-sports people. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2019, 9, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Li, T.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, R.C.; Qiu, G. Differential proteome analysis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18834–e18847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, S.R.; Qiu, G.X.; Zhang, J.G.; Zhuang, Q.Y. Research progress on the etiology and pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, Y.; Kou, I.; Scoliosis, J.; Matsumoto, M.; Watanabe, K.; Ikegawa, S. Genome-wide association study for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Clin. Calcium 2016, 26, 553–560. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mao, S.H.; Qian, B.P.; Shi, B.; Zhu, Z.Z.; Qiu, Y. Quantitative evaluation of the relationship between COMP promoter methylation and the susceptibility and curve progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggio, C.L.; Giampietro, P.F.; Dobrin, S.; Chengfeng, Z.; Dorshorst, D.; Ghebranious, N.; Weber, J.L.; Blank, R.D. A novel locus for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis on chromosome 12p. J. Orthop. Res. 2009, 27, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V.; Fong, G.C.; Luk, K.D.; Yip, B.; Lee, M.K.; Wong, M.S.; Lu, D.D.S.; Chan, T.W. A genetic locus for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis linked to chromosome 19p13.3. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 71, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, C.A.; Barnes, R.; Gillum, J.; Herring, J.A.; Bowcock, A.M.; Lovett, M. Localization of susceptibility to familial idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2000, 25, 2372–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, L.B.; Mangino, M.; De Serio, S.; De Cicco, D.; Capon, F.; Semprini, S.; Pizzuti, A.; Noveli, G.; Dallapiccola, B. Assignment of a locus for autosomal dominant idiopathic scoliosis (IS) to human chromosome 17p11. Hum. Genet. 2002, 111, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, C.M.; Miller, N.H.; Marosy, B.; Zhang, J.; Wilson, A.F. Familial idiopathic scoliosis: Evidence of an X-linked susceptibility locus. Spine 2003, 28, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcuende, J.A.; Minhas, R.; Dolan, L.; Stevens, J.; Bek, J.; Wang, K.; Weinstein, S.L.; Sheffield, V. Allelic variants of human melatonin 1A receptor in patients with familial adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2003, 28, 2025–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiardes, S.; Veile, R.; Allen, M.; Wise, C.A.; Dobbs, M.; Morcuende, J.A.; Szappanos, L.; Herring, J.A.; Bowcock, A.M.; Lovett, M. SNTG1, the gene encoding gamma1-syntrophin: A candidate gene for idiopathic scoliosis. Hum. Genet. 2004, 115, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, N.H.; Justice, C.M.; Marosy, B.; Doheny, K.F.; Pugh, E.; Zhang, J.; Dietz, H.C., III; Wilson, A.F. Identification of candidate regions for familial idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2005, 30, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alden, K.J.; Marosy, B.; Nzegwu, N.; Justice, C.M.; Wilson, A.F.; Miller, N.H. Idiopathic scoliosis: Identification of candidate regions on chromosome 19p13. Spine 2006, 31, 1815–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Gordon, D.; Zhang, D.; Browne, R.; Helms, C.; Gillum, J.; Weber, S.; Devroy, S.; Swaney, S.; Dobbs, M.; et al. CHD7 gene polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to idiopathic scoliosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaka, L.; Zhao, C.; Reed, J.A.; Ebenezer, N.D.; Brice, G.; Morley, T.; Mehta, M.; O’Dowd, J.; Weber, J.L.; Hardcastle, A.J.; et al. Assignment of two loci for autosomal dominant adolescent idiopathic scoliosis to chromosomes 9q31.2-q34.2 and 17q25.3-qtel. J. Med. Genet. 2008, 45, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurnett, C.A.; Alaee, F.; Bowcock, A.; Kruse, L.; Lenke, L.G.; Bridwell, K.H.; Kuklo, T.; Luhmann, S.J.; Dobbs, M.B. Genetic linkage localizes an adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and pectus excavatum gene to chromosome 18 q. Spine 2009, 34, e94–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gao, X.; Londono, D.; Devroy, S.E.; Mauldin, K.N.; Frankel, J.T.; Brandon, J.M.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q.-Z.; Dobbs, M.B.; et al. Genome-wide association studies of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis suggest candidate susceptibility genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kou, I.; Takahashi, A.; Johnson, T.A.; Kono, K.; Kawakami, N.; Uno, K.; Ito, M.; Minami, S.; Yanagida, H.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies common variants near LBX1 associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1237–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajchenberg, M.; Astur, N.; Kanas, M.; Martins, D.E. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Current concepts on neurological and muscular etiologies. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2016, 11, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchuk, D.Y.; Bekshaev, S.S.; Bumakova, S.A.; Dudin, M.G.; Pinchuk, O.D. Bioelectric activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus-pineal gland system in children with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. ISRN Orthop. 2012, 2012, 987095–987101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yim, A.P.-y.; Yeung, H.-y.; Sun, G.; Lee, K.-m.; Ng, T.-b.; Lam, T.-p.; Ng, B.K.-w.; Qiu, Y.; Moreau, A.; Cheng, J.C.-y. Abnormal skeletal growth in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is associated with abnormal quantitative expression of melatonin receptor, MT2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6345–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Minami, S.; Nakata, Y.; Kitahara, H.; Otsuka, Y.; Isobe, K.; Takaso, M.; Tokunaga, M.; Nishikawa, S.; Tetsuro, M.; et al. Association between estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and curve severity of idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2002, 27, 2357–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helenius, I.; Remes, V.; Yrjönen, T.; Ylikoski, M.; Schlenzka, D.; Helenius, M.; Poussa, M. Does gender affect outcome of surgery in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Spine 2005, 30, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenanidis, E.; Potoupnis, M.E.; Papavasiliou, K.A.; Sayegh, F.E.; Kapetanos, G.A. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and exercising: Is there truly a liaison? Spine 2008, 33, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampietro, P.F.; Blank, R.D.; Raggio, C.L.; Merchant, S.; Jacobsen, F.S.; Faciszewski, T.; Shukla, S.K.; Greenlee, A.R.; Reynolds, C.; Schowalter, D.B. Congenital and idiopathic scoliosis: Clinical and genetic aspects. Clin. Med. Res. 2003, 1, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, C.; Li, M. High selenium may be a risk factor of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Med. Hypotheses 2010, 75, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, M.E. Heated indoor swimming pools, infants, and the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A neurogenic hypothesis. Environ. Health 2011, 10, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayssoux, R.S.; Cho, R.H.; Herman, M.J. A history of bracing for idiopathic scoliosis in North America. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, H. Brace Treatment for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Jo, H.R.; Park, S.H.; Sung, W.S.; Keum, D.H.; Kim, E.J. The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for scoliosis: A protocol for systematic review and/or meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e23238-42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.T.; Chen, K.C.; Chiu, E.H. Adult degenerative scoliosis treated by acupuncture. J. Altern. Complement Med. 2009, 15, 935–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.R.; Bohr, S.; Jahnke, A.; Pleines, S. Acupucture in the treatment of scoliosis—A single blind controlled pilot study. Scoliosis 2008, 3, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, A.J. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Indications for bracing and conservative treatments. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misterska, E.; Głowacki, J.; Głowacki, M.; Okręt, A. Long-term effects of conservative treatment of Milwaukee brace on body image and mental health of patients with idiopathic scoliosis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193447-67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, H.; Pripp, A.H.; Lange, J.E.; Brox, J.I. Predictors for long-term curve progression after Boston brace treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.; Wright, J.G.; Hedden, D. A comparative study of TLSO, Charleston, and Milwaukee braces for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 1998, 23, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addai, D.; Zarkos, J.; Bowey, A.J. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2020, 36, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganjavian, M.S.; Behtash, H.; Ameri, E.; Khakinahad, M. Results of Milwaukee and Boston Braces with or without Metal Marker Around Pads in Patients with Idiopathic Scoliosis. Acta Med. Iran. 2011, 49, 598–605. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D.E.; Richards, B.S.; Browne, R.H.; Herring, J.A. A comparison between the Boston brace and the Charleston bending brace in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 1997, 22, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.R.; Thakur, N.A.; Eberson, C.P. Brace management in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lonstein, J.E.; Winter, R.B. The Milwaukee brace for the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A review of one thousand and twenty patients. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1994, 76, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, C.T.; Scott, D.S.; Reed, F.R., Jr.; Sproul, J.T.; Riddick, M.F. Nighttime bracing for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with the Charleston Bending Brace: Long-term follow-up. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1997, 17, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.E.; Durrani, A.A. Factors that influence outcome in bracing large curves in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2001, 26, 2354–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amato, C.R.; Griggs, S.; McCoy, B. Nighttime bracing with the Providence brace in adolescent girls with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2001, 26, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coillard, C.; Vachon, V.; Circo, A.B.; Beausejour, M.; Rivard, C.H. Effectiveness of the SpineCor brace based on the new standardized criteria proposed by the scoliosis research society for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2007, 27, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwicki, T.; Chowanska, J.; Kinel, E.; Czaprowski, D.; Tomaszewski, M.; Janusz, P. Optimal management of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescence. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2013, 4, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parr, A.; Askin, G. Paediatric scoliosis: Update on assessment and treatment. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Takeshita, K. Surgical treatment of scoliosis: A review of techniques currently applied. Scoliosis 2008, 3, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, S.; Lee, S.; Chung, E.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Selective Thoracic Fusion With Segmental Pedicle Screw Fixation in the Treatment of Thoracic Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2005, 30, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, T.; Bilgic, S.; Ersen, O.; Yurttas, Y.; Oguz, E.; Sehirlioglu, A.; Kazanci, A. The importance and efficacy of posterior only instrumentation and fusion for severe idiopathic scoliosis. Turk. Neurosurg. 2012, 22, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Potter, B.K.; Kuklo, T.R.; Lenke, L.G. Radiographic outcomes of anterior spinal fusion versus posterior spinal fusion with thoracic pedicle screws for treatment of Lenke Type I adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. Spine 2005, 30, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.N.; Upasani, V.V.; Bastrom, T.P.; Marks, M.C.; Pawelek, J.B.; Betz, R.R.; Lenke, L.; Newton, P. Spontaneous lumbar curve correction in selective thoracic fusions of idiopathic scoliosis: A comparison of anterior and posterior approaches. Spine 2008, 33, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohara, A.; Kawakami, N.; Saito, T.; Tsuji, T.; Ohara, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Ryoji, T.; Kazuki, K. Comparison of Surgical Outcomes Between Anterior Fusion and Posterior Fusion in Patients With AIS Lenke Type 1 or 2 that Underwent Selective Thoracic Fusion-Long-term Follow-up Study Longer Than 10 Postoperative Years. Spine 2015, 40, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sucato, D.J.; Agrawal, S.; O’Brien, M.F.; Lowe, T.G.; Richards, S.B.; Lenke, L. Restoration of thoracic kyphosis after operative treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A multicenter comparison of three surgical approaches. Spine 2008, 33, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Pan, F.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Y. A comparison of anterior and posterior instrumentation for restoring and retaining sagittal balance in patients with idiopathic adolescent scoliosis. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2012, 25, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, M.F.; Singla, A.; Feger, M.A.; Sauer, L.D.; Novicoff, W. Surgical treatment of Lenke 5 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Comparison of anterior vs. posterior approach. World J. Orthop. 2016, 7, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Ni, J.; Fang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhu, X.; He, S.; Gu, S.; Wang, X. Comparison of selective anterior versus posterior screw instrumentation in Lenke5C adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2009, 34, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanji, F.; Nasto, L.A.; Bastrom, T.; Samdani, A.F.; Yaszay, B.; Clements, D.; Shah, S.; Lonner, B.; Betz, R.; Shufflebarger, H.L.; et al. A Detailed Comparative Analysis of Anterior Versus Posterior Approach to Lenke 5C Curves. Spine 2018, 43, e285–e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, P.R.; Grevitt, M.P.; Sell, P.J. Anterior or posterior surgery for right thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS)? A prospective cohorts’ comparison using radiologic and functional outcomes. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2015, 28, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, H.; Ito, M.; Kaneda, K.; Shono, Y.; Takahata, M.; Abumi, K. Long-term outcomes of anterior spinal fusion for treating thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves: Average 15-year follow-up analysis. Spine 2013, 38, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandhari, H.; Ameri, E.; Nikouei, F.; Haji Agha Bozorgi, M.; Majdi, S.; Salehpour, M. Long-term outcome of posterior spinal fusion for the correction of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Wang, W.; Shen, M.; Xia, L. Anterior versus posterior approach in Lenke 5C adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A meta-analysis of fusion segments and radiological outcomes. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2016, 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Rong, L. Comparison of combined anterior-posterior approach versus posterior-only approach in treating adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A meta-analysis. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourfeizi, H.H.; Sales, J.G.; Tabrizi, A.; Borran, G.; Alavi, S. Comparison of the Combined Anterior-Posterior Approach versus Posterior-Only Approach in Scoliosis Treatment. Asian Spine J. 2014, 8, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbs, M.B.; Lenke, L.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Luhmann, S.J.; Bridwell, K.H. Anterior/posterior spinal instrumentation versus posterior instrumentation alone for the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliotic curves more than 90 degrees. Spine 2006, 31, 2386–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShizShi, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Qiao, Y.; Guo, K.; Xiangyang, C.; et al. Comparison of Thoracoscopic Anterior Release Combined With Posterior Spinal Fusion Versus Posterior-only Approach With an All-pedicle Screw Construct in the Treatment of Rigid Thoracic Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2015, 28, e454–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).