Associations between Developing Sexuality and Mental Health in Heterosexual Adolescents: Evidence from Lower- and Middle-Income Countries—A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Identified Studies

3.2. Quality Assessment

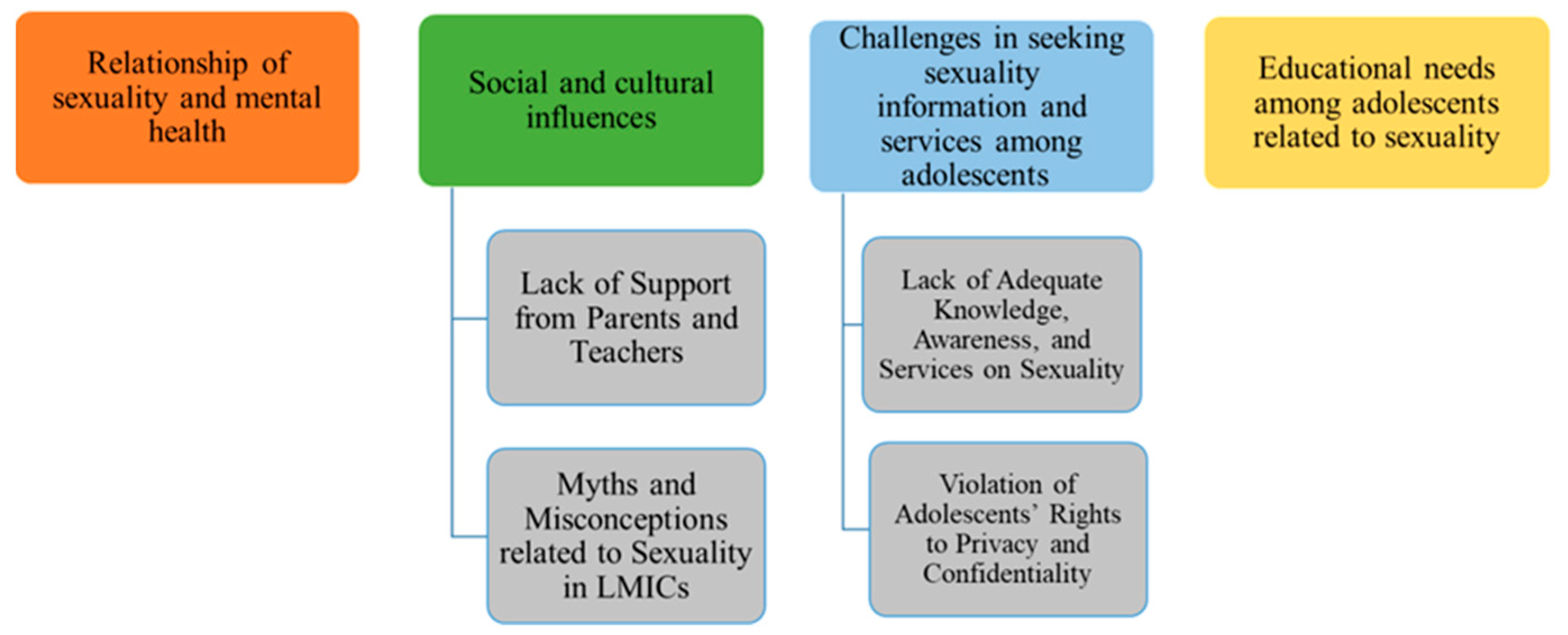

3.3. Major Themes

3.4. Relationship of Sexuality and Mental Health

3.5. Social and Cultural Influences

3.6. Lack of Support from Parents and Teachers

3.7. Myths and Misconceptions Related to Sexuality in LMICs

3.8. Challenges in Seeking Sexuality Information and Services among Adolescents Lack of Adequate Knowledge, Awareness, and Services on Sexuality

3.9. Violation of Adolescents’ Rights to Privacy and Confidentiality

3.10. Educational Needs among Adolescents Related to Sexuality and Mental Health

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| S # | Title, Author, Country, and Year | Population Sample and Age | Purpose of the Study | Study Design and Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A Different Approach in Developing a Sexual Self-Concept Scale for Adolescents in Accra, Ghana Authors: Biney, A. A. E. Country: Ghana Year: 2016 | Quantitative:

| To explore if there are significant relationships between adolescents’ sexual self-concept and their sexual and mental health | Mixed Method: Quantitative:

| Quantitative findings:

|

| 2 | Mental Well-being and Self-reported Symptoms of Reproductive Tract Infections among Girls: Findings from a Cross-sectional Study in an Indian Slum Authors: Khopkar, S. A., Kulathinal, S., Virtanen, S. M., & Säävälä, M. Country: India | 10–18-year-old adolescent girls (n = 85) | To assess the associations between socio-demographic variables, physical health indicators, and adolescent post-menarcheal girls’ mental well-being. | Quantitative study: Cross-sectional personal interview survey | The mean and standard deviation of the mental well-being score (scale 0 to 12) were 8 and 3. Each post-menarcheal girl in the inner-city slum was classified as having a low (score 0 to 8) or high (score 9 to 12) score. A total of 36 girls had low scores, while 49 had high scores. The level of maturation gave an indication of potentially being related to worsening mental well-being scores. |

| Year: 2017 | Nearly every other post-menarcheal girl reported having experienced symptoms suggestive of reproductive tract infections during the last twelve months. | ||||

| 3 | Emotional and Psychosocial Aspects of Menstrual Poverty in Resource-Poor Settings: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Adolescent Girls in an Informal Settlement in Nairobi Authors: Crichton, J., Okal, J., Kabiru, C. W., & Zulu, E. M. Country: Nairobi, Kenya Year: 2013 | Adolescent girls aged 12 to 17 years to ensure our sample reflected variations in age (12–14, 15–17 age groups) | To examine the impact of menstrual poverty on the emotional well-being of adolescent girls in an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya | Qualitative study purposive quota sampling open-ended interview questions 15 in-depth interviews (IDIs) and 10 focus group discussions (FGDs) A total of 87 girls participated in FGDs | Girls experienced psychosocial deprivations, including limited access to information and lack of emotional and practical support with menstruation from parents and family members. Lack of reliable access to menstrual products was a major cause of physical discomfort, embarrassment, anxiety, fear of being stigmatized and low mood. Participants used language, such as “feeling bad,” feeling “stressed”, or “fearful” and “wanting to cry”, to describe the emotional distress. Negative feelings were associated with menstrual poverty and caused anxiety during school days. Hormone-related symptoms of fatigue and mood symptoms, including tension and depressed mood, are highly prevalent among menstruating girls regardless of social context or menstrual poverty. |

| 4 | Unmet medical care and sexual health counseling needs: a cross-sectional study among university students in Uganda Authors: Kyagaba, E., Asamoah, B. O., Emmelin, M., & Agardh, A. Country: Uganda Year: 2014 | n = 1954 students below the age of 24 56% male and 44% female | To investigate unmet medical care and sexual health counseling needs among the study population chosen (Ugandan university students) in order to see how these needs are associated with mental health, social capital, religion, and sexual behavior. | Quantitative study: self-administered questionnaire containing 132 items | The majority of students (81%) reported having good self-rated health, but 51% said they had unmet medical needs, and 26% reported unmet sexual health counseling needs. Students with high mental health scores (i.e., poor mental health, p-value < 0.001) who practiced inconsistent condom use (p-value 0.0059, p-value 0.006), who had experienced sexual coercion (p-value < 0.001), and who had poor self-rated health (p-value < 0.001) had a higher prevalence of both unmet medical care and sexual health counseling needs. The association between risky sexual behaviors among men and unmet sexual and reproductive health service needs explained by the fear of being stigmatized or punished for sexual activity when seeking care. Poor mental health is highly stigmatized and individuals who are perceived as having a low mental health status seem to be less willing to seek health care. |

| 5 | Adolescents’ Responses to an Unintended Pregnancy in Ghana: A Qualitative Study Authors: Aziato, L., Hindin, M. J., Maya, E. T., Manu, A., Amuasi, S. A., Lawerh, R. M., & Ankomah, A. Country: Ghana Year: 2016 | 92 adolescents girls, aged 13–19 years | To investigate the experiences and perceptions of adolescents who have experienced a recent pregnancy and undergone a termination of pregnancy. To clarify if the sample had indeed experienced pregnancy | Qualitative study: A vignette-based focus group approach with fifteen FGDs | Adolescents reported that the characters in the vignettes would feel sadness, depression, and regret from unintended pregnancies. Most participants believed the parents of a pregnant adolescent in the vignette would not be happy about the pregnancy and the parents’ potential reactions would range from sadness and annoyance to anger and abuse. Health care professionals are a source of stress as they are likely to be judgmental and disrespectful. |

| 6 | Menarche stories: reminiscences of college students from Lithuania, Malaysia, Sudan, and the United States. Authors: Joan, C. C., & Zittel, P. C. B Country: 26 Lithuanians, 27 Americans, 20 Malaysians, and 23 Sudanese Year: 1998 | 26 Lithuanian, 27 American, 20 Malaysian, and 23 Sudanese girls The Malaysian students were 19 to 20 years old The Sudanese women’ s average age was 20 years old | This study aims to understand and analyze the experience of first menstruation, emotional reaction, preparedness, sources of information about menstruation, changes in body image, and celebrations of this rite of passage. | Qualitative study: Female psychology students were invited to write the story of their first menstruation. | The most common emotions mentioned by the Malaysians were fear and embarrassment, followed closely by worry. The most common emotion mentioned by the Sudanese was fear; also common were anxiety, embarrassment, and anger. |

| 7 | Physical, Social, and Political Inequities Constraining Girls’ Menstrual Management at Schools in Informal Settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Authors: Girod, C., Ellis, A., Andes, K. L., Freeman, M. C., & Caruso, B. A. Country: Kenya Year: 2017 | Schoolgirls 6–11 post-menarchal girls in grades 6–8 | This study documents differences between girls’ experience of menstruation at public schools (where the Kenyan government provides menstrual pads) and private schools (where pads are not provided) in two informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. | Qualitative study: focus group discussion (FGD) with girls | Girls experienced fear and anxiety due to harassment from male peers and had incomplete information about menstruation from teachers. Girls in every school had fear and anxiety about getting infections. They worried about negative health outcomes due to poor menstrual management, and they believed that urine splattering onto the vulva could cause urinary tract infections, gonorrhea, or infertility. |

| 8 | Adolescent perception of reproductive health care services in Sri Lanka. Authors: Agampodi, S. B., Agampodi, T. C., & Piyaseeli, U. K. D. Country: Sri Lanka Year: 2008 | 32 adolescents between 13 males and 19 females 17–19 years of age | The purpose of this study was to explore the perceived reproductive health problems, health-seeking behaviors, knowledge about available services and barriers to reach services among a group of adolescents in Sri Lanka in order to improve reproductive health service delivery. | Qualitative study: four focus group discussions | Psychological distresses due to various reasons and problems regarding the menstrual cycle and masturbation are the most common health problems. |

| 9 | The importance of a positive approach to sexuality in sexual health programs for unmarried adolescents in Bangladesh. Authors: van Reeuwijk, M., & Nahar, P. Country: Bangladesh. Year: 2013 | Young, unmarried adolescents of 12–18 years | To explore the mismatch that exists between what unmarried adolescents in Bangladesh experience, want and need with regard to their sexuality and what they receive from their society, which negatively impacts on their understanding of sexuality and their well-being. | Qualitative study: in-depth interviews, focus group discussion, observations, and content analysis | Many girls expressed worries and various misconceptions about the issue of virginity and were insecure about their ability to prove their own virginity. Boys were curious about masturbation and wet dreams and about the size and shape of the penis and duration of intercourse. Boys felt bad for having wet dreams and a number felt guilty after masturbating. |

| 10 | Adolescent and Parental Reactions to Puberty in Nigeria and Kenya: A Cross-Cultural and Intergenerational Comparison. Authors: Bello, B. M., Fatusi, O., Adepoju, O. E., Maina, W., Kabiru, C. W., Sommer, M., & Mmari, K. Country: Nigeria and Kenya Year: 2017 | Sixty-six boys and girls (aged 11 to 13 years) | To assess the reactions of adolescents and their parents to puberty in urban poor settings in two African countries Nigeria (Ile-Ife) in West Africa, and Kenya (Nairobi) in East Africa and compared the experiences of current adolescents to that of their parents’ generation. | Qualitative study | Adolescents’ reactions to puberty-related bodily changes varied from anxiety, shame, to pride, and an increased desire for privacy. |

| 11 | Factors impacting on menstrual hygiene and their implications for health promotion. Authors: Lahme, A. M., Stern, R., & Cooper Country: Zambia Year: 2018 | 51 respondents, aged 13–20 years | This paper explores the factors influencing the understanding, experiences and practices of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in Mongu District, Western Province of Zambia. | Explorative Qualitative study Six focus group discussions | Girls suffer from poor menstrual hygiene, originating from lack of knowledge, culture and tradition, and socio-economic and environmental constraints, leading to inconveniences, humiliation and stress. This leads to reduced school attendance and poor academic performance, or even dropouts, and ultimately infringes upon the girls’ human rights. |

| 12 | Menstrual knowledge and practices of female adolescents in Vhembe district, Limpopo Province, South Africa Authors: Ramathuba, D. U. Country: South Africa Year: 2015 | 14–19 years 273 secondary school girls doing Grades 10–12 | This study sought to assess the knowledge and practices of secondary school girls towards menstruation in the Thulamela municipality of Limpopo Province, South Africa. | A quantitative descriptive study design | 73% of girls reported having fear and anxiety at the first experience of bleeding |

References

- Haberland, N.A.; McCarthy, K.J.; Brady, M. A systematic review of adolescent girl program implementation in low-and middle-income countries: Evidence gaps and insights. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kar, S.K.; Choudhury, A.; Singh, A.P. Understanding normal development of adolescent sexuality: A bumpy ride. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzma, E.K.; Peters, R.M. Adolescent vulnerability, sexual health, and the NP’s role in health advocacy. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2016, 28, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatusi, A.O. Young people’s sexual and reproductive health interventions in developing countries: Making the investments count. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mmari, K.; Astone, N. Urban adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-income and middle-income countries. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krafft-Ebing, R. Psychopathia Sexualis; Rebman, F.J., Translator; Medical Art Agency: New York, NY, USA, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Sheerin, F.; McKenna, H. Defining sexuality for holistic nursing practice: An analysis of the concept. All Irel. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2000, 1, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Defining Sexual Health: Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health, 28–31 January 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sh/en/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Westheimer, R.K.; Lopater, S. Human Sexuality: A Psychosocial Perspective; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; McCarraher, D.R.; Phillips, S.J.; Williamson, N.E.; Hainsworth, G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: Needs, barriers, and access. Reprod. Health 2014, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salam, R.A.; Das, J.K.; Lassi, Z.S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Adolescent health and well-being: Background and methodology for review of potential interventions. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patton, G.C.; Coffey, C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Viner, R.M.; Haller, D.M.; Bose, K.; Vos, T.; Ferguson, J.; Mathers, C.D. Global patterns of mortality in young people: A systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009, 374, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mortality Estimates by Cause, Age, and Sex for the Year 2008–2011; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring Health for the SDGs Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, B.; Ferguson, B.J. Health for the world’s adolescents: A second chance in the second decade. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Opportunity in Crisis: Preventing HIV from Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood. 2011. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/opportunity-in-crisis-preventing-hiv-from-early-adolescence-to-young-adulthood/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Banerji, M.; Martin, S.; Desai, S. Is Education Associated with a Transition towards Autonomy in Partner Choice. A Case Study of India; India Human Development Survey Working Paper; University of Maryland: College Park, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Santhya, K.G.; Haberland, N.; Singh, A.K. She Knew Only When the Garland Was Put around Her Neck’: Findings from an Exploratory Study on Early Marriage in Rajasthan; Population Council: New Delhi, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Santhya, K.G.; Ram, U.; Acharya, R.; Jejeebhoy, S.J.; Ram, F.; Singh, A. Associations between early marriage and young women’s marital and reproductive health outcomes: Evidence from India. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2010, 36, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, L.J.; Raffaelli, M.; Moilanen, K.L. Adolescent Sexuality: Behavior and Meaning; Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska: Stony Brook, NY, USA, 2003; p. 245. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Caldwell, C.H. Growth trajectories of sexual risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensel, D.J.; Nance, J.; Fortenberry, J.D. The association between sexual health and physical, mental, and social health in adolescent women. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandfort, T.G.; Orr, M.; Hirsch, J.S.; Santelli, J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: Results from a national US study. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.; Brooke-Sumner, C.; Baingana, F.; Baron, E.C.; Brever, E. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: A systematic review of reviews. Lancet 2018, 5, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Chisholm, D.; Dua, T.; Laxminarayan, R.; Vos, T. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: Key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2016, 387, 1672–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sayers, J. The world health report 2001-Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 1085. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Bassi, M.; Junnarkar, M.; Negri, L. Mental health and psychosocial functioning in adolescence: An investigation among Indian students from Delhi. J. Adolesc. 2015, 39, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M. Positive sexuality and its impact on overall well-being. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2013, 56, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agampodi, S.B.; Agampodi, T.C.; Piyaseeli, U.K.D. Adolescents perception of reproductive health care services in Sri Lanka. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aziato, L.; Hindin, M.J.; Maya, E.T.; Manu, A.; Amuasi, S.A.; Lawerh, R.M.; Ankomah, A. Adolescents’ Responses to an Unintended Pregnancy in Ghana: A Qualitative Study. J. Pediatric Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016, 29, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisler, J.C.; Zittel, C.B. Menarche stories: Reminiscences of college students from Lithuania, Malaysia, Sudan, and the United States. Health Care Women Int. 1998, 19, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Crichton, J.; Okal, J.; Kabiru, C.W.; Zulu, E.M. Emotional and psychosocial aspects of menstrual poverty in resource-poor settings: A qualitative study of the experiences of adolescent girls in an informal settlement in Nairobi. Health Care Women Int. 2013, 34, 891–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, C.; Ellis, A.; Andes, K.L.; Freeman, M.C.; Caruso, B.A. Physical, Social, and Political Inequities Constraining Girls’ Menstrual Management at Schools in Informal Settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahme, A.M.; Stern, R.; Cooper, D. Factors impacting on menstrual hygiene and their implications for health promotion. Glob. Health Promot. 2018, 25, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Reeuwijk, M.; Nahar, P. The importance of a positive approach to sexuality in sexual health programmes for unmarried adolescents in Bangladesh. Reprod. Health Matters 2013, 21, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khopkar, S.A.; Kulathinal, S.; Virtanen, S.M.; Säävälä, M. Mental Wellbeing and Self-reported Symptoms of Reproductive Tract Infections among Girls. Finn. Yearb. Popul. Res. 2017, 52, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kyagaba, E.; Asamoah, B.O.; Emmelin, M.; Agardh, A. Unmet medical care and sexual health counseling needs—A cross-sectional study among university students in Uganda. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2014, 25, 1034–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramathuba, D.U. Menstrual knowledge and practices of female adolescents in Vhembe district, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Curationis 2015, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Biney, A.A.E. A Different Approach in Developing a Sexual Self-Concept Scale for Adolescents in Accra, Ghana. Sex. Cult. 2016, 20, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluye, P.; Robert, E.; Cargo, M.; Bartlett, G.; O’Cathain, A.; Griffiths, F.; Boardman, F.; Gagnon, M.P.; Rousseau, M.C. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2011. In Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews; McGill University, Department of Family Medicine: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, B.M.; Fatusi, A.O.; Adepoju, O.E.; Maina, B.W.; Kabiru, C.W.; Sommer, M.; Mmari, K. Adolescent and parental reactions to puberty in Nigeria and Kenya: A cross-cultural and intergenerational comparison. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, S35–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roudsari, R.L.; Javadnoori, M.; Hasanpour, M.; Hazavehei, S.M.M.; Taghipour, A. Socio-cultural challenges to sexual health education for female adolescents in Iran. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 11, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Shoveller, J.A.; Johnson, J.L.; Langille, D.B.; Mitchell, T. Socio-cultural influences on young people’s sexual development. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motsomi, K.; Makanjee, C.; Basera, T.; Nyasulu, P. Factors affecting effective communication about sexual and reproductive health issues between parents and adolescents in zandspruit informal settlement, Johannesburg, South Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 25, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, G.; Ventriglio, A.; Bhugra, D. Sexuality and mental health: Issues and what next? Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokororo, A.; Kihunrwa, A.; Hoekstra, P.; Kalluvya, S.E.; Changalucha, J.M.; Fitzgerald, D.W.; Downs, J.A. High prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in pregnant adolescent girls in Tanzania: A multi-community cross-sectional study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2015, 91, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lince-Deroche, N.; Hargey, A.; Holt, K.; Shochet, T. Accessing sexual and reproductive health information and services: A mixed methods study of young women’s needs and experiences in Soweto, South Africa. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2015, 19, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glasier, A.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Schmid, G.P.; Moreno, C.G.; Van Look, P.F. Sexual and reproductive health: A matter of life and death. Lancet 2006, 368, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddlecom, A.; Awusabo-Asare, K.; Bankole, A. Role of parents in adolescent sexual activity and contraceptive use in four African countries. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2009, 35, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namisi, F.S.; Flisher, A.J.; Overland, S.; Bastien, S.; Onya, H.; Kaaya, S.; Aarø, L. Sociodemographic variations in communication on sexuality and HIV/AIDS with parents, family members and teachers among in-school adolescents: A multi-site study in Tanzania and South Africa. Scand. J. Public Health 2009, 37 (Suppl. 2), 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Kohan, S.; Shamsi-Gooshki, E.; Shahriari, M. Ethical considerations in sexual health research: A narrative review. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahanonu, E.L. Attitudes of healthcare providers towards providing contraceptives for unmarried adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2014, 8, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, K.; Crutzen, R.; Krumeich, A.; Roman, N.; van den Borne, B.; Reddy, P. Healthcare workers’ beliefs, motivations and behaviours affecting adequate provision of sexual and reproductive healthcare services to adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hindin, M.J.; Christiansen, C.S.; Ferguson, B.J. Setting research priorities for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Pisa, P.T.; Imrie, J.; Beery, M.P.; Martin, C.; Skosana, C.; Delany-Moretlwe, S. Assessment of adolescent and youth friendly services in primary healthcare facilities in two provinces in South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rankin, K.; Heard, A.; Diaz, N. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: Scoping the Impact of Programming in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. 3ie Scoping Pap. 2016, 5, 4–86. [Google Scholar]

- Santhya, K.G.; Jejeebhoy, S.J. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls: Evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Glob. Public Health 2015, 10, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hall, K.S.; Morhe, E.; Manu, A.; Harris, L.H.; Ela, E.; Loll, D.; Kolenic, G.; Dozier, J.L.; Challa, S.; Zochowski, M.K.; et al. Factors associated with sexual and reproductive health stigma among adolescent girls in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nyblade, L.; Stockton, M.; Nyato, D.; Wamoyi, J. Perceived, anticipated andexperienced stigma: Exploring manifestations and implications for young people’s sexual and reproductive health and access to care in North-Western Tanzania. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 19, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wamoyi, J.; Fenwick, A.; Urassa, M.; Zaba, B.; Stones, W. “Women’s bodies are shops”: Beliefs about transactional sex and implications for understanding gender power and HIV prevention in Tanzania. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2011, 40, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health. Making Health Services Adolescent Friendly: Developing National Quality Standards for Adolescent Friendly Health Services. 2012. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75217/1/9789241503594eng.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Alford, J. Public value from co-production by clients. Public Sect. 2009, 32, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, R.W.; Mmari, K.; Moreau, C. It begins at 10: How gender expectations shape early adolescence around the world. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, S3–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hallman, K.K.; Kenworthy, N.J.; Diers, J.; Swan, N.; Devnarain, B. The shrinking world of girls at puberty: Violence and gender-divergent access to the public sphere among adolescents in South Africa. Glob. Public Health 2015, 10, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, S.; Bustreo, F.; Kuo, T.; Mishra, C.K.; Taylor, K.; Fogstad, H.; Gupta, G.R.; Gilmore, K.; Temmerman, M.; Thomas, J.; et al. The Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030): A roadmap based on evidence and country experience. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spider Tool | Justification |

|---|---|

| S—Sample | Adolescents (10–19 years) |

| PI—Phenomenon of Interest | Experiences of developing sexuality and associated mental health issues/psychological well-being |

| D—Design | Qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods |

| E—Evaluation | Experience and perceptions of adolescent girls and boys |

| R—Research type | Mixed method designs |

| Spider Tool | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| S—Sample | “young” OR “teen*” OR “youth*” OR “low and middle-income countr*” OR “Developing countr*” OR “South Asia” OR “low and middle-income countr*” |

| PI—Phenomenon of Interest | “sex” OR “sexual health” OR “sexuality” OR “mental health” OR “puberty” OR “stress*” OR “anxiety” OR “mental disorder* OR “depress*” OR “psychological well-being” |

| D—Design | “questionnaire*” OR “survey*” OR “interview*” OR “focus group*” OR “case stud*” OR “observ*” |

| Study Design | Selected Studies | Appraisal Score |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Studies | Crichton, Kenya, 2013 | 100% (****) |

| Aziato et al., Ghana, 2016 | 50% (**) | |

| Girod et al., Kenya, 2017 | 100% (****) | |

| Joan et al., Malaysia, 1998 | 50% (**) | |

| Agampodi et al., Sri Lanka, 2008 | 50% (**) | |

| van Reeuwijk, Bangladesh, 2016 | 100% (****) | |

| Bello et al., Kenya, 2017 | 100% (****) | |

| Lahme et al., Zambia, 2018 | 75% (***) | |

| Quantitative Studies | Kyagaba et al., Uganda, 2014 | 100% (****) |

| Khopkar et al., India, 2017 | 75% (***) | |

| Ramathuba, South Africa, 2015 | 75% (***) | |

| Mixed Method | Biney, Ghana, 2016 | 100% (****) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Punjani, N.S.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Hegadoren, K.; Hirani, S.; Mumtaz, Z.; Jackson, M. Associations between Developing Sexuality and Mental Health in Heterosexual Adolescents: Evidence from Lower- and Middle-Income Countries—A Scoping Review. Adolescents 2022, 2, 164-183. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020015

Punjani NS, Papathanassoglou E, Hegadoren K, Hirani S, Mumtaz Z, Jackson M. Associations between Developing Sexuality and Mental Health in Heterosexual Adolescents: Evidence from Lower- and Middle-Income Countries—A Scoping Review. Adolescents. 2022; 2(2):164-183. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020015

Chicago/Turabian StylePunjani, Neelam Saleem, Elizabeth Papathanassoglou, Kathleen Hegadoren, Saima Hirani, Zubia Mumtaz, and Margot Jackson. 2022. "Associations between Developing Sexuality and Mental Health in Heterosexual Adolescents: Evidence from Lower- and Middle-Income Countries—A Scoping Review" Adolescents 2, no. 2: 164-183. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020015

APA StylePunjani, N. S., Papathanassoglou, E., Hegadoren, K., Hirani, S., Mumtaz, Z., & Jackson, M. (2022). Associations between Developing Sexuality and Mental Health in Heterosexual Adolescents: Evidence from Lower- and Middle-Income Countries—A Scoping Review. Adolescents, 2(2), 164-183. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020015