Ethnic Identity, Implicit Associations, and Academic Motivation of Hispanic Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Intersection of Ethnic Identity and Stereotype Threat

1.2. The School Context

1.3. Sub-Conscious Processes

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

Participants

3. Measures

3.1. Survey

3.2. Implicit Associations Test (IAT)

3.3. Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Correlations Among Ethnic Identity and Motivation Variables

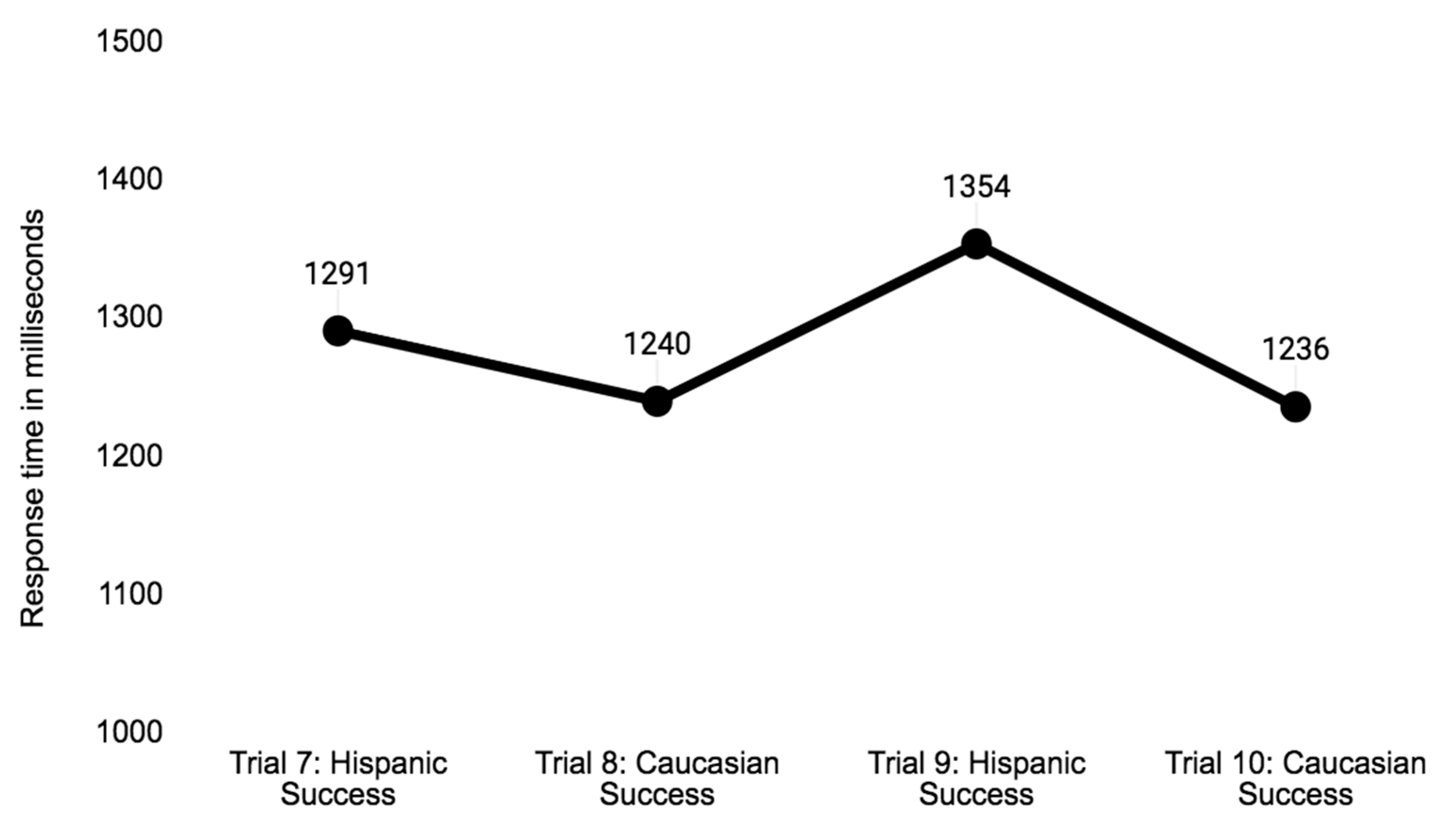

4.2. Implicit Associations Test (IAT) Results

4.3. Association between Ethnic Identity and Implicit Associations

5. Discussion

5.1. The Associations among Ethnic Identity and Academic Motivation

5.2. Implicit Associations

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Sellers, R.M.; Smith, M.A.; Shelton, J.N.; Rowley, S.A.; Chavous, T.M. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 2, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavous, T.; Rivas-Drake, D.; Smalls, C.; Griffin, T.; Cogburn, C. Gender matters: The influence of school racial discrimination experiences and racial identity on academic adjustment among African American Adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Witkow, M.; Garcia, C. Ethnic identity and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinney, J.S.; Cantu, C.L.; Kurtz, D.A. Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 1997, 26, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, J.U. Understanding cultural diversity and learning. Educ. Res. 1992, 21, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyll, M.; Madon, S.; Prieto, L.; Scherr, K.C. The potential roles of self-fulfilling prophecies, stigma consciousness, and stereotype threat in linking Latino/a ethnicity and educational outcomes. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 66, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, A.; Buendia, E.; Crosland, K.; Doumbia, F. The production of margin and center: Welcoming-unwelcoming of immigrant students. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Berrera, A. The Way Hispanics Describe Themselves Vary across Immigrant Generations. Pew Research Center, 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/24/the-ways-hispanics-describe-their-identity-vary-across-immigrant-generations/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Oakes, J. Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, M.; Weber, S.; Kronberger, N. The influence of stereotype threat on immigrants: Review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, A.; Hernandez, P.R.; Estrada, M.; Schultz, P.W. The consequences of chronic stereotype threat: Domain disidentification and abandonment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, S.; Kronberger, N.; Appel, M. Immigrant students’ educational trajectories. The influence of cultural identity and stereotype threat. Self. Identity 2018, 17, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, B.E. Stereotype boost and stereotype threat effects: The moderating role of ethnic identification. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2010, 16, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Urdan, T. Ethnic identity, academic motivation, and stereotype threat. In Proceedings of the Bi-Annual Meetings of the International Conference on Motivation, Helsinki, Finland, 12 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Erba, J. Media representations of Latina/os and Hispanic students’ stereotype threat behavior. Howard J. Commun. 2018, 29, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.K.; Hartson, K.A.; Binning, K.R.; Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Garcia, J.; Taborsky-Barba, S.; Tomassetti, S.; Nussbaum, A.D.; Cohen, G.L. Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: How self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 591–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.W.; Feather, N.T. A Theory of Achievement Motivation; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. Am. Psychol. 1985, 40, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, O.C.; Rösch, A.G.; Rawolle, M.; Kullmann, J.; Kordik, A. Implicit motives: Current topics and future directions. In Advances in Motivation and Achievement, V. 16A: The Decade Ahead; Urdan, T., Karabenick, S., Eds.; Emerald Press: Castle Hill, NSW, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagleman, D. Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bassili, J.N. Response Latency and the Accessibility of Voting Intentions: What Contributes to Accessibility and How it Affects Vote Choice. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, R.H.; Dunton, B.C. Categorization by race: The impact of automatic and controlled components of racial prejudice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 33, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, C.W.; Gurtman, M.B. Evidence for the automaticity of ageism. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 26, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.A. Accommodation Without Assimilation: Sikh Immigrants in an American High School; Cornell University Press: Ithica, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcόn, O.; Szalacha, L.A.; Erkut, S.; Fields, J.P.; Coll, C.G. The Color of My Skin: A Measure to Assess Children’s Perceptions of Their Skin Color. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2000, 4, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C.; Maehr, M.L.; Hruda, L.; Anderman, E.; Anderman, L.; Freeman, K.; Kumar, R.; Gheen, M.; Kaplan Middleton, M.; Nelson, J.; et al. Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales; University of Michigan: Ann Abor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In Acculturation: Theory, Models, and Some New Findings; Padilla, A., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1980; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Contexts of acculturation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Sam, D.L., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W.; Phinney, J.S.; Sam, D.L.; Vedder, P. Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 55, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronin, E.; Steele, C.M.; Ross, L. Identity bifurcation in response to stereotype threat: Women and mathematics. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 40, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, R.H.; Olson, M.A. Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.N.; Thongniramol, O. Immigration and self-reported delinquency: The interplay of immigration generations, gender, race, and ethnicity. J. Crime Justice 2005, 28, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, N.A.; Fabrett, F.C.; Knight, G.P. Acculturation, enculturation, and the psychosocial adaptation of Latino youth. In Handbook of U.S. Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives; Villarruel, F.A., Carlo, G., Grau, J.M., Azmitia, M., Cabrera, N.J., Chahin, T.J., Eds.; Sage Publications Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, A.M. Bicultural Social Development. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2006, 28, 467–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Kelly, P. The back pocket map: Social class and cultural capital as transferable assets in the advancement of second-generation immigrants. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2008, 620, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U. The Implicit Association Test: A Method in Search of a Construct. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaji, M.R.; Greenwald, A.G. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People; Delacorte Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, B.K.; Vuletich, H.A.; Lundberg, K.B. The bias of crowds: How implicit bias bridges personal and systemic prejudice. Psychol. Inq. 2017, 28, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentale, F.; Vecchione, M.; Gebauer, J.E.; Barbaranelli, C. Measuring automatic value orientations: The Achievement–Benevolence Implicit Association Test. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 57, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, A.; Steinman, R.B. The Single Category Implicit Association Test as a measure of implicit social cognition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, J.R.; Olson, K.R. Test-retest reliability and predictive validity of the Implicit Association Test in children. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 308–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Variable | Percentage in Each Category |

|---|---|

| Gender | 50% male, 50% female |

| Grade | 49% 9th, 49% 10th, 1% 11th, 1% 12th |

| First language spoken | 85% Spanish as first language, 15% English as first language |

| Parent graduated high school | 26% at least one parent graduated high school, 74% neither parent graduated high school |

| Student is immigrant | 27.4% immigrant, 72.6% born in U.S. |

| One or both parents are immigrants | 80% had at least one immigrant parent, 20% had parents born in U.S. |

| Mean (S.D.) | EI-C | EI-R | ASC | AV | SA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI: Centrality | 3.80 (1.08) | -- | ||||

| EI: Regard | 3.87 (0.81) | 0.50 ** | -- | |||

| Academic SC | 3.29 (0.89) | 0.29 ** | 0.21 | -- | ||

| Academic value | 3.82 (0.94) | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.47 ** | -- | |

| Belonging | 4.04 (1.08) | −0.04 | 0.28 * | 0.19 | 0.34 ** | |

| Stereotype awareness | 3.31 (1.33) | 0.23 * | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urdan, T.; Teramoto, D. Ethnic Identity, Implicit Associations, and Academic Motivation of Hispanic Adolescents. Adolescents 2021, 1, 252-266. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030019

Urdan T, Teramoto D. Ethnic Identity, Implicit Associations, and Academic Motivation of Hispanic Adolescents. Adolescents. 2021; 1(3):252-266. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030019

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrdan, Tim, and Daniel Teramoto. 2021. "Ethnic Identity, Implicit Associations, and Academic Motivation of Hispanic Adolescents" Adolescents 1, no. 3: 252-266. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030019

APA StyleUrdan, T., & Teramoto, D. (2021). Ethnic Identity, Implicit Associations, and Academic Motivation of Hispanic Adolescents. Adolescents, 1(3), 252-266. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030019