1. Introduction

Water is the essence of life, and ensuring its quality is crucial for a sustainable future. In recent years, the increasing presence of emerging contaminants in water bodies has become a global concern due to their potential effects on living organisms. Emerging contaminants (EC) are recently found chemicals that are formed naturally or synthetically and not monitored in the environment. They are causing serious threats to the environment and to human health. These contaminants include various products, such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and personal care products. They can persist in the ecosystem for a long period of time, which can lead to long-term effects on aquatic organisms and human beings due to direct exposure or due to the bioaccumulation process in the food chain [

1]. All these call for the need for advanced detection methods and implementing proper regulations for controlling the release and transportation of these materials.

One of the major challenges in handling ECs is the identification of its sources. Source identification is an essential part of controlling pollution, regulatory enforcement, and assessing risk, among other applications [

2]. Without this, mitigation efforts may become unsuccessful, thereby continuing environmental degradation and its associated effects. Environmental forensic methods help in determining the sources of emerging contaminants and designing targeted remediation measures. This includes gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, isotope ratio mass spectrometry, remote sensing and geographical information systems, statistical modeling, and machine learning techniques [

3].

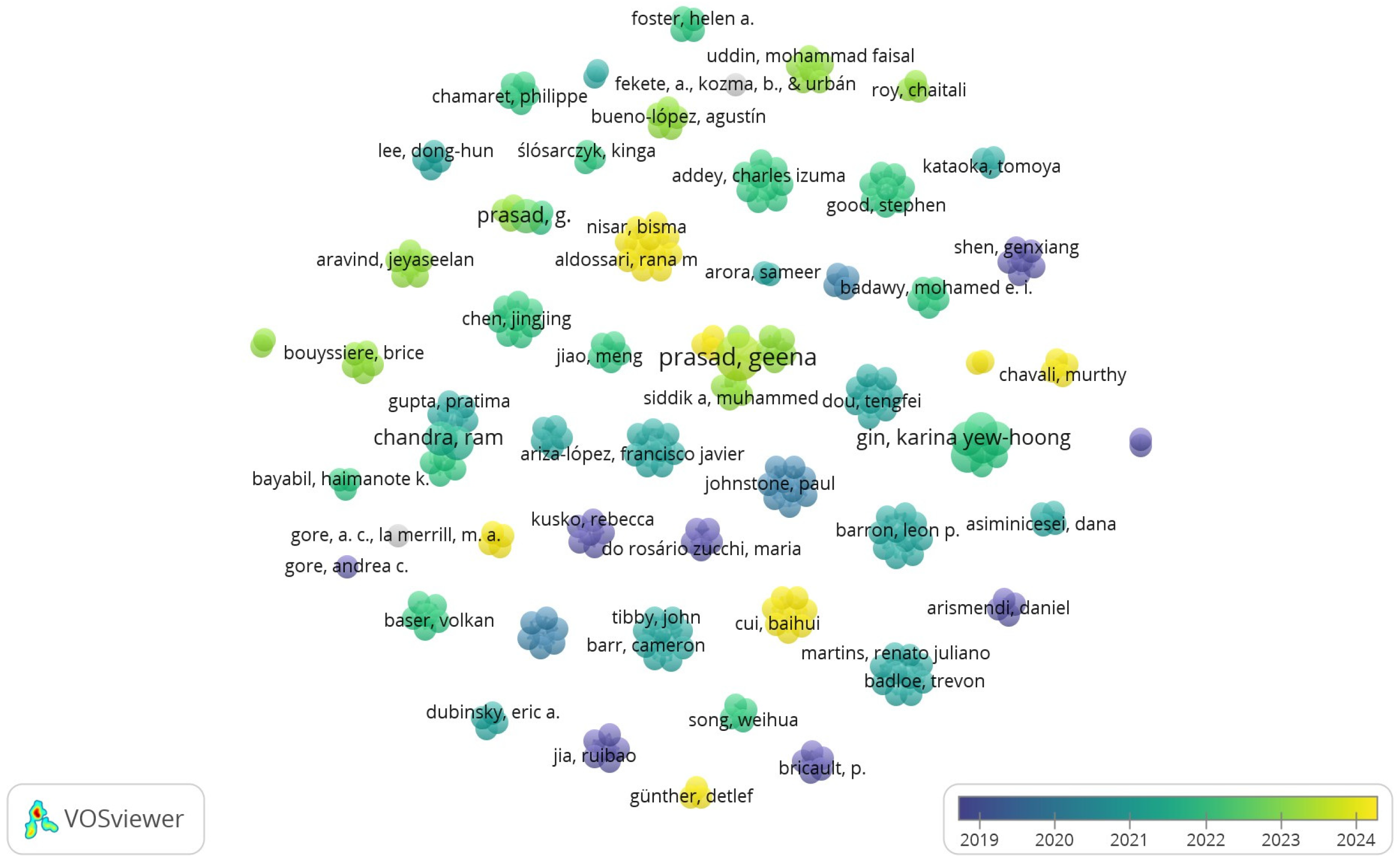

This review processed 58 articles, including original articles and review articles. For conducting the literature survey, sources like Google Scholar, Refseek, Science Direct, and Scopus were used. The searching was carried out with keywords such as emerging contaminants, forensic techniques, spectroscopy, statistical method, and machine learning techniques. The literature study was intended to provide a comprehensive understanding of the environmental forensics approach for emerging contaminants, especially in water. To create a map of the bibliographic data used to prepare the review, VOSviewer version 1.6.20 was used.

Figure 1 presents the overlay visualization of keyword co-occurrence generated using VOSviewer. The node size indicates the keyword frequency, and the color scale represents the average publication year of the manuscripts with the selected keywords. The evolution of the research themes over the years was visualized in blue or cyan, which represent earlier studies, or yellow, which shows more recent studies. Earlier studies were mostly centered on the occurrence, detection, and health-related impacts of conventional and emerging water contaminants; the research themes gradually evolved toward advanced analytical techniques, source attribution, and data-driven environmental forensic approaches through a period dominated by method development, validation, and applied monitoring studies (green nodes).

While emerging contaminants are frequently studied from environmental monitoring and public health perspectives, their investigation within a forensic science framework remains comparatively underdeveloped. Environmental forensics extends beyond contaminant detection to address questions of source attribution, responsibility, temporal reconstruction, and evidentiary reliability, often under regulatory or legal scrutiny. In this context, analytical techniques are evaluated not only for sensitivity but also for specificity, reproducibility, traceability, and their capacity to support defensible conclusions.

This review explicitly frames emerging contaminant analysis within an environmental forensic paradigm, emphasizing how analytical, spatial, and data-driven methods can be used to reconstruct contamination events, discriminate between competing sources, and support enforcement and remediation actions.

2. Emerging Contaminants in Aquatic Environments

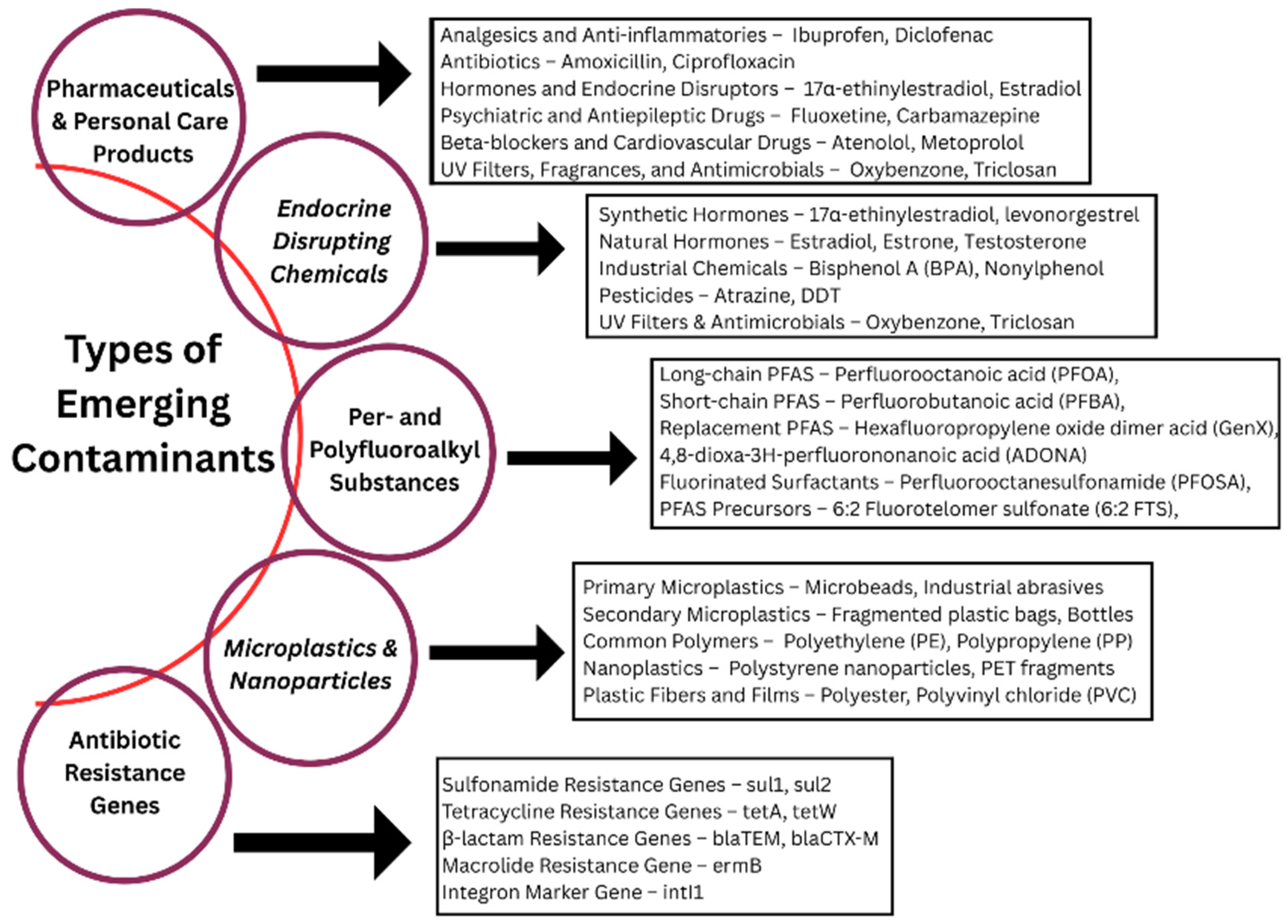

Given below are the key insights on emerging contaminants in the aquatic environment (

Figure 2).

2.1. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products

Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCP) primarily consist of products that are used daily, like cosmetics, fragrances, medications, hygiene products, etc. In today’s world, the production and use of these materials have drastically increased, and their discharge into the environment without any control is raising global concern. The presence of medicine, including disinfecting substances, analgesics, antibiotics, and similar items, has been found in freshwater systems and groundwater worldwide [

4]. Most of these chemicals are interminable, and by bioaccumulation in cell tissue, they can be transferred into fruits, vegetables, crops, and drinking water sources [

5]. PPCPs can cause many health hazards by interrupting hormonal systems, leading to reproductive issues and providing resistance to antibiotics, especially in wildlife [

6].

2.2. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are natural or man-made chemicals that may block, mimic, or interfere with hormones, which are part of the endocrine system. In the human body, they bioaccumulate in adipose tissue, have long half-lives, and can cause latent health effects such as infertility, hormone-sensitive cancers, and metabolic disorders, especially in vulnerable populations like fetuses and neonates [

7].

Studies have found approximately 1000 such chemical substances with similar properties [

7,

8,

9]. EDCs include industry chemicals, pesticides, metals, pharmaceutical agents, fungicides, phytoestrogens, etc. They usually enter and persist in the environment through agricultural runoff, improper disposal, and wastewater and can accumulate in the food chain, potentially affecting human and wildlife health [

10].

2.3. Microplastics and Nanoparticles

Microplastics and nanoparticles are tiny particles that pose significant environmental and health risks due to their small size and persistence in ecosystems. Plastic particles having a size less than 5 mm (diameter) and resulting from the disintegration of big plastic debris or from other products like cleaning agents, personal care products, etc., are called microplastics (MPs) [

11]. Their presence in the entire environment is increasing. Organisms may feed on these particles, leading to physical harm, a polluted food chain, and chemical toxicity due to the absorption of harmful substances on their surface.

Nanoparticles (NPs) are tiny particles that have a size of less than 1 µm. They are formed through the degradation of large plastic materials due to environmental factors like mechanical abrasion, microbial activity, and ultraviolet radiation. They are more dangerous than microplastics, as they can penetrate biological membranes, accumulate in tissues, and interact with cells at the molecular level, in turn increasing toxicity and having a long-term impact on the environment [

12].

The presence of MPs and NPs in food, water, and air raises significant concerns regarding their impact on human health. Studies suggest that the ingestion and inhalation of these particles can lead to inflammation, oxidative stress, and potential toxicity in living organisms [

11,

13].

2.4. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of man-made chemicals that have utility in our day-to-day life activities. They are mainly used because of their water-, oil-, and stain-repellent nature. PFAS can be found in products like non-stick cookware, cosmetics, food packaging, firefighting foam, water-repellent clothing, personal care products, etc. These chemicals can enter the environment through wastewater treatment plant effluent, discharge from industries, or the degradation of consumer products. Because of their persistence in the environment, PFAS are often called ‘forever chemicals’, as they do not break down easily, remaining in water, soil, and living organisms over time [

14]. In general, PFAS with a negative charge are more mobile in soil than neutral and positively charged ones and can lead to groundwater pollution. It has also been found that PFAS having long carbon chains have more retaining capacity in soil than short-chain compounds [

15]. Continuous exposure to PFAS can lead to many health problems involving liver damage, developmental delays, disruption in the immune system, and increased risks of certain cancers [

16].

2.5. Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are genes found in microorganisms like bacteria, fungi, etc., that enable them to resist the effects of antibiotics designed to kill or inhibit their growth. These genes can be naturally present in bacteria or acquired through mutations and horizontal gene transfer via plasmids, transposons, or bacteriophages [

17]. ARGs encode proteins that neutralize antibiotics, alter drug targets, or expel antibiotics from bacterial cells, making infections harder to treat [

18]. These genes can occur naturally in microorganisms or develop through mutations and horizontal gene transfer, allowing bacteria to survive in the presence of antibiotics [

19]. ARGs are commonly carried on plasmids, which are small DNA molecules that can be transferred between bacteria, spreading resistance across bacterial populations.

There has been a rapid increase in the spread of ARGs in the environment due to the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in human medicine and veterinary medicine, particularly in animal husbandry, livestock production, and agriculture. When antibiotics are used excessively or improperly, bacteria are exposed to sub-lethal concentrations, which can promote the development of resistance. ARGs can spread to environmental bacteria through wastewater effluent, agricultural runoff, and animal waste, contributing to the onset of antibiotic-resistant infections in humans and animals [

17]. These infections are more difficult to treat and are associated with increased mortality rates and healthcare costs.

3. Sources of Emerging Contaminants in Water Systems

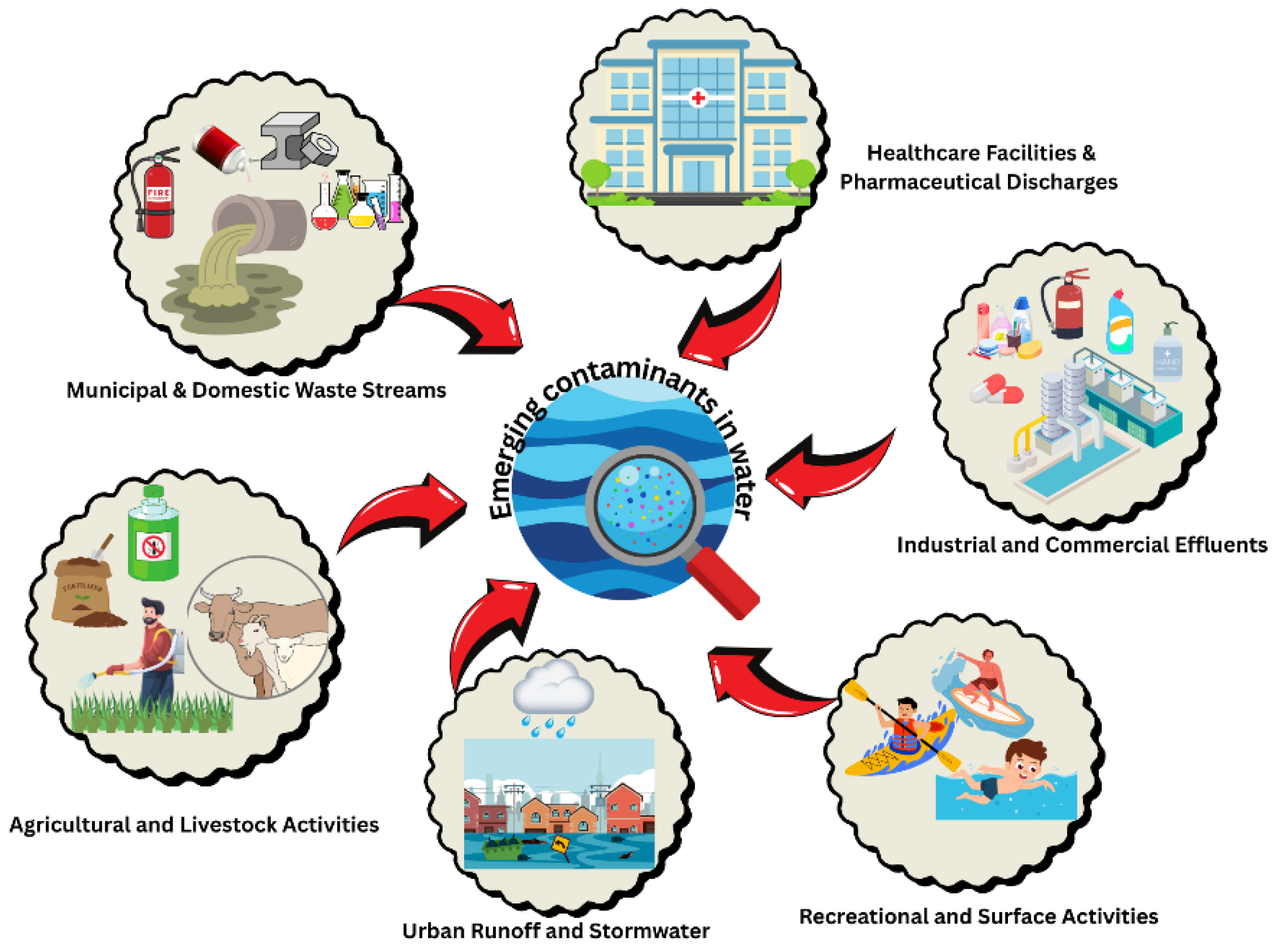

The presence of emerging contaminants in water bodies can be due to various reasons, but it is mainly due to anthropogenic actions. These include discharges from industry, household effluents, agricultural runoff, urban runoff, etc. (

Figure 3). Identifying the sources of contaminants is a crucial part of environmental monitoring and pollution control.

3.1. Municipal and Domestic Waste Streams

Municipal and domestic activities are one of the major contributors to the presence of emerging contaminants in water systems. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) act as a primary point, as they receive inputs from institutions, commercial establishments, households, etc., which consist of disinfectants, pharmaceuticals, flame retardants, plasticizers, and personal care products. The traditional treatment methods can largely remove conventional pollutants but are inefficient in the removal of ECs due to their low concentration, chemical diversity, and persistence. The unscientific disposal of cleaning agents, PPCs, medications, antibacterial soaps, washing synthetic fabrics, etc., directly contributes to the presence of ECs in wastewater. When wastewater containing these compounds is released into water bodies, it may persist, bioaccumulate, or associate with aquatic organisms [

18].

3.2. Healthcare Facilities and Pharmaceutical Discharges

Healthcare institutions like hospitals, pathology laboratories, and clinics are primary contributors to the presence of ECs in water, particularly through pharmaceutical wastes. These institutions contribute biologically active compounds, including hormones, analgesics, antibiotics, and contrast agents, to water. In contrast to the domestic effluents, the wastewater from these areas contains compounds that are more persistent, toxic, or resistant to degradation. If the wastewater from hospitals and related institutions is discharged into municipal sewers without any pretreatment, it can cause biologically active compounds to approach WWTPs, which are not designed to treat them properly. The effluents from pharmaceutical manufacturing industries can also contribute to ECs as they contain active pharmaceutical ingredients [

4].

3.3. Agricultural and Livestock Activities

Agriculture and livestock farming are prime non-point sources of ECs in both groundwater and surface water systems. In agricultural areas, several chemicals like fungicides, pesticides, and fertilizers are used more, leading to their presence in nearby biota. In the animal husbandry field, the exponential use of growth-promoting hormones, antibiotics, and antiparasitic drugs is contributing greatly to the EC load in the environment. Through leaching or surface runoff, pharmaceuticals, natural and artificial hormones, fungicides, pesticides, and herbicides can reach water bodies, especially during precipitation or irrigation [

19].

3.4. Industrial and Commercial Effluents

Industries and commercial areas related to tanning, paper and pulp, petroleum refineries, plastics manufacturing, chemical production, and textiles produce a variety of organic and inorganic compounds like solvents, fire retarders, metals, surfactants, and PFAS, which results in the distribution of emerging contaminants in the environment, especially in water bodies, as many of the traditional WWTPs cannot remove such impurities. If the treatment is improper, even leachate from landfills can cause the migration of contaminants into nearby surface waters and groundwater. These compounds, especially PFAS, can persist for extended periods of time in the water, causing long-term impacts in humans [

18].

3.5. Urban Runoff and Stormwater

Precipitation, particularly rainfall, initiates the buildup of heavy metals, particles from tire wear, road dust, and remnants of personal care products on impervious surfaces like pavements, rooftops, and roads. These chemicals will reach stormwater systems, which often lack a treatment facility, and ultimately water bodies. This will result in the presence of various emerging contaminants in the water, leading to urban areas being considered one of the significant non-point sources of ECs [

4,

18].

3.6. Recreational and Surface Activities

Recreational activities in and around water bodies, like boating, swimming, surfing, and bathing, can contribute to the discharge of insect repellents, body lotions, sunscreens, and other personal care products directly into the water, mostly untreated. These products contain ingredients like UV filters (e.g., oxybenzone) and fragrances, which are difficult to degrade and will persist, causing many effects to humans and aquatic organisms [

19].

4. Forensic Techniques for Source Identification in Water

For environmental monitoring and mitigation of pollution, it is crucial to identify the contaminant source. Different forensic methods aid in tracing them to their origin, thereby supporting regulatory actions and remediation strategies.

4.1. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is a method for the identification and quantification of volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds like pesticides, pharmaceuticals, etc. It yields mass spectral fingerprints that help in tracing the source of pollution. Initially, the sample is separated into individual components depending on its volatility and the GC component’s interaction with the column’s stationary phase. They become ionized and fragmented when they enter the mass spectrometer and are analyzed based on their mass-to-charge ratio [

20]. The resulting mass spectra help in the identification and quantification of the compounds [

21].

Rotating-disk sorptive extraction (RDSE)-derivatization-GC/MS-optimized analytical strategy was proposed for the multiclass identification of ECs in water samples, which helps in the determination of 16 emerging contaminants, including hormones, parabens, and anti-inflammatory drugs. The method exhibits high selectivity and sensitivity, allowing for the identification of various compounds in environmental samples [

22].

Another study demonstrated the use of portable GC-MS for on-site detection of organic contaminants in water samples. It demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity, comparable to that of laboratory instruments, allowing instant identification of pollutants like petroleum hydrocarbons and chlorinated solvents [

23].

Experiments were conducted by some researchers on the identification of hazardous organic pollutants in industrial wastewater using a multi-tiered approach, emphasizing GC-MS for the identification of compounds. Volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds (including phthalates, hydrocarbons, phenols, and halogenated compounds, of which most are genotoxic agents or endocrine disruptors) were efficiently distinguished qualitatively and to a certain extent quantitatively using GC-MS. A comparative study was performed between mass spectra and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library to enable precise identification of the compounds. By linking bioassays (cytotoxicity, phytotoxicity, and genotoxicity) with results from GC-MS, a complete toxicological profile was also made [

24].

The use of pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) in the detection and quantification of nanoplastics in aquatic environments was proven to be effective by the experiments conducted by Xu et al. They identified six key polymer types—polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PETE or PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), and polystyrene (PS)—in groundwater and surface water samples after ultrafiltration and oxidative digestion. The results show a significantly higher concentration of NPs in surface water, with PE and PP dominating the detected fractions, demonstrating the method’s reliability in environmental forensics for characterizing trace-level complex pollutant mixtures [

25].

An innovative method of thermal extraction-desorption gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (TED-GC/MS) was initiated for effectively detecting microplastics in water samples by Sorolla-Rosario. It consists of thermally treating entire filters containing collected solids directly, easing sample handling and cutting down on potential contamination. This method improves precision and effectiveness in microplastic analysis, underlining the importance of GC-MS methods in the identification of emerging contaminants and environmental monitoring [

26].

In a recent study, GC-MS was adopted as a main analytical tool for detecting and quantifying nanoplastics in both environmental and drinking water samples. The method demonstrates high accuracy and sensitivity in detecting nanoscale plastic particles. GC-MS enables the separation of polymer types depending on their thermal degradation products, allowing for the precise determination of materials such as PP, PE, and PS [

27].

4.2. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

LC-MS/MS is an analytical method that combines liquid chromatography for distinguishing complex mixtures with tandem mass spectrometry for highly sensitive and unique identification of compounds. LC differentiates the compounds in the liquid phase, and MS/MS detects them by analyzing their mass-to-charge ratios and fragmentation patterns. This technique is used in analyzing non-volatile and heat-sensitive contaminants like hormones, antibiotics, and pharmaceuticals [

19].

An integrated method of solid-phase extraction (SPE) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was introduced for the identification and quantification of organic contaminants (pharmaceuticals, pesticides, etc.) in potable water samples. The effectiveness of SPE in the reduction of analytes was observed, which helps in enhancing the sensitivity and selectivity of the LC-MS/MS analysis. This study demonstrates the ability of the LC-MS/MS method for the detection of emerging contaminants in water at a trace level if used along with suitable sample preparation techniques [

28].

For achieving high specificity and sensitivity for polar and thermally unstable compounds, ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has played a significant role, especially in complex biological and environmental matrices. A study conducted by Loos et al. used SPE followed by UHPLC-MS/MS and GC-MS to identify a variety of pollutants, including personal care products, pesticides, industrial chemicals, and pesticides in water, fish tissue, and suspended particulate matter (SPM) collected during the Joint Danube Survey [

29].

A new method incorporating SPE and LC-MS was developed by Wang et al. (2019) to detect the presence of pesticides and their degradation products in water, which helps in the early reduction of analytes from complex water matrices and their subsequent identification by LC-MS. The reduced detection limits and high recovery rates make the method more suitable for the periodic examination of trace-level pesticide contamination in water resources [

30].

For identifying trace organic contaminants in water, a combination of the online solid-phase extraction technique and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was used, which combines hydrophilic-lipophilic balance and ion-exchange interactions in a single extraction process. It helps in improving the retention and recovery of contaminants, including industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides [

31].

Recent studies show that LC-MS/MS is a proven tool for the detection of ECs, particularly volatile and thermally unstable compounds (pharmaceuticals, personal care products, polyfluoroalkyl substances, etc.) in drinking water samples, which underscores its usage in monitoring contaminants and risk assessment [

30,

31,

32].

4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy relies on passing infrared (IR) waves through a sample and estimating the amount of light absorbed at various wavelengths. Each molecule absorbs IR light at a particular frequency that corresponds to the vibration of its chemical bonds. The final spectrum shows characteristic absorption peaks, which disclose the functional groups and molecular structure of the sample [

18].

In the identification of microplastics in water, air, sediment, biota, etc., FTIR is the widely accepted method. In this method, MPs are identified by assessing their characteristic absorption spectra and collating them with reference polymer libraries. As each polymer type poses different ecological risks, the advantage of FTIR in differentiating various polymer types plays a crucial role in understanding and managing plastic pollution [

33].

A rapid analytical technique for the characterization and quantification of MPs in tap water was developed by Mukotaka et al. using FTIR microscopy [

34]. Without any complex sample preparation, this method enables the direct identification of MPs in membrane filters. Due to its potential to evaluate polymer-specific vibrational spectra, it was able to identify microplastics like PET, PP, and PE, even at trace amounts. This work highlights the efficiency, non-destructive nature, and molecular specificity of FTIR microscopy, reinforcing its utility as a frontline technique for monitoring microplastic contamination in drinking water systems [

34].

In another study, FTIR was able to differentiate organic matter sourced from aquatic plants, terrestrial plants, and microbial biomass in lake sediments using FTIR technology. The FTIR method enabled the separation between allochthonous (external) and autochthonous (internal) in the organic content of sediments, showing that it is suitable for analysis in lacustrine environments and paleoenvironmental reconstructions [

35].

4.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

In this method, a liquid sample to be tested is fed to high-temperature argon plasma, and it is vaporized, atomized, and ionized there. These ions are directed to a mass spectrometer, and they are differentiated based on their mass-to-charge ratio and identified [

18].

Wysocka and Vassileva formulated a method using high-resolution sector field inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HR-SF-ICP-MS) for the determination of fourteen rare earth metals (REEs) in open seawater samples. It consisted of pre-concentration of REEs by co-precipitation of Fe (OH)

3 followed by cation–exchange purification to eliminate matrix interferences, resulting in a detection limit ranging from 0.7 to 2.7 picomoles per kilogram and precise quantification of REEs [

36]. For the identification of microplastics, the application of ICP-MS was studied by analyzing the carbon-13 signal and found to be effective for detecting trace amounts [

37].

Vonderach et al. and Hendriks and Mitrano studied the importance of inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ICP-TOFMS)-based methods for the identification and characterization of MPs and NPs in complex matrices [

38,

39]. For the identification of nanoplastics, Castillo et al. (2023) adopted the spICP-MS method, in which metal-based tags are used to address the difficulties related to their ultra-small size and very low mass. Several studies found that metal tagging facilitates the accurate analysis of concentration and particle size distribution [

40,

41]. Vonderach et al. formulated a total consumption microdroplet ICP-TOFMS method for precisely quantifying carbon content in biological cells and microplastic particles individually [

38]. By analyzing carbon–12 signals, Hendriks and Mitrano used single-particle ICP–TOFMS (sp-ICP-TOFMS) to distinguish MPs from biological particles such as algae and natural organic matter [

39].

4.5. Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS)

Isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) calculates the ratios of stable isotopes (e.g., (

2H/

1H), (

34S/

32S)) in a sample with accuracy. Initially, the sample is converted into simple gases like CO

2 or N

2 by pyrolysis or combustion. Then it is taken by an inert gas to the mass spectrometer where it is ionized and travels through a magnetic field. Depending on their mass-to-charge ratios, the ions become separated, and sensors record the relative abundance of each isotope [

19].

Dos Santos et al. used IRMS for calculating stable isotopic ratios of hydrogen

2H/

1H and oxygen

18O/

16O in water samples, which provided higher precision, especially for hydrogen studies. The method was found to be more sensitive to instrumental and procedural conditions that call for accurate calibration and corrections [

41].

The IRMS method was used in a study conducted in the Kozlowa Góra reservoir catchment in southern Poland to find the origin of contamination by considering the isotopes of sulfur (δ

34S), nitrogen (δ

15N and δ

18O in nitrate), and oxygen (δ

18O in sulfate), and was able to clearly distinguish between anthropogenic and natural sources of pollution. It shows notable pollution from agricultural runoff consisting of manure, fertilizers, and municipal wastewater [

42].

Stable isotope ratios of each pesticide compound were measured using GC-IRMS or LC-IRMS for tracing and managing pesticide residues in the environment, which highlights the importance of integrating IRMS and compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA) in the analysis [

43].

4.6. Remote Sensing and Geographical Information Systems

Remote sensing (RS) uses sensors, satellites, and drones to find contamination of water, whereas geographical information system (GIS) assesses spatial data to map pollution as well as to model the contamination spread [

44]. Multispectral and hyperspectral imaging, thermal infrared sensors, and synthetic aperture radar in RS technologies help in identifying pollutants in the water bodies [

45]. These methods are effective in finding fuel spills, agricultural runoffs, and plant emissions. For example, algal blooms can be detected by hyperspectral imaging, while temperature differences in wastewater discharge can be detected by thermal imaging. Recent advances in nanophotonics, particularly the development of integrated photonic circuits, metasurfaces, and optical phased arrays, have shown promise in overcoming the limitations of traditional optical sensing systems for mapping water body changes in pollution-induced sedimentation and erosion. While primarily explored in light detection and ranging (LiDAR) applications, these innovations in light manipulation and compact optical device design open new opportunities for environmental forensics, where precise, rapid, and miniaturized detection systems are critical for identifying contaminants in water [

46]. GIS enables hydrological modeling to simulate contaminant dispersion, finds high-risk pollution zones, and helps time-series analysis to track pollution trends [

47]. Another study used statistical methods and GIS to evaluate the health risks and water-quality impacts of arsenic pollution in the Kızılırmak River in Turkey. Using GIS mapping, the study identifies spatial hotspots of contamination and reveals that exposure to river water poses a carcinogenic risk to adults, mainly from arsenic concentrations. This integrated approach highlights the effectiveness of GIS-based environmental forensics in uncovering hidden pollutant distributions and guiding risk management strategies [

48].

4.7. Statistical Modeling

This method evaluates complicated datasets to find sources, pollution patterns, and trends in water quality while distinguishing geogenic pollution disparities caused by anthropogenic activities [

49]. To categorize the pollutants and to find their sources, multivariate statistical techniques (principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis (CA)) are commonly used. PCA reduces large datasets into key variables, making it easier to identify pollutant signatures, while CA groups similar contamination patterns, helping to distinguish between different pollution sources [

50]. In source distribution, by computing the aids of various contamination sources, other cutting-edge statistical methods, like discriminant analysis and positive matrix factorization, can be used [

51]. To find the uncertainty and probabilistic relationships between pollutants and their sources, Bayesian models were used in another study [

52]. A study by Ariza-López illustrates three instances of the multi-domain application of the integration of statistical methods with GIS—spatial data quality in statistical data, statistical process modeling in geospatial data, and linking statistical data to geospatial data. The integration of statistical models with GIS provides a powerful method for environmental forensic study, allowing the development of extrapolative models [

53].

4.8. Machine Learning Techniques

The correlations between various factors like hydrologic variables, land cover, weather and microbial sources in the Russian River watershed in Northern California were studied using six machine learning algorithms—naive Bayes, simple neural network (NN), random forest (RF), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), support vector machine (SVM) and XGBoost—which were able to predict the major sources of contaminants by microbes along with the identification of influencing factors as precipitation and temperature [

18].

XGBoost performed best in classifying the microbial sources into human and non-human causes, with a high accuracy of 88% and an area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.88 [

54]. A hybrid modeling framework combining process-based models having data-driven machine learning methods consisting of random forest and support vector regression was used for predicting the concentration of emerging contaminants, considering basic water quality indicators (e.g., turbidity, pH, nutrients), and resulted in obtaining a non-linear relationship of EC levels and standard water quality parameters with high accuracy and workability [

55]. In a study, 52 samples of water were collected from five sources, including municipal wastewater, headwater, livestock manure, suburban runoff, and agricultural runoff, for analysis. Using non-target high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data in combination with support vector classification for the selection of key chemical features, the method achieved an accuracy of approximately 100%, demonstrating its high efficiency in contaminant source tracking [

56].

Using a combination of machine learning and a passive sampling method, ECs (pesticides, pharmaceuticals, etc.) were detected during the summer and winter seasons in the River Thames. The retention time of the contaminants was able to be predicted using machine learning (ML), which improved suspect screening and enhanced detection accuracy [

57].

4.9. Comparison of Analytical Methods for Environmental Forensics

Parameters like high precision, accuracy, robustness, sensitivity, and reproducibility across complex matrices must be satisfied by the analytical methods, especially from an environmental forensic perspective, in order to ensure reliable recognition and legal feasibility. Forensic investigations mostly depend on combining various analytical lines of evidence for the reconstruction of contamination scenarios, which is not commonly employed in normal environmental monitoring.

In environmental forensics, chromatography–mass spectrometry techniques (GC–MS and LC–MS/MS) are mainly considered as confirmatory tools because of their compound-specific identification capability. Typical limits of detection for organic emerging contaminants range from 0.1 to 10 ng L

−1 for GC–MS and 0.01–1 ng L

−1 for LC–MS/MS, with recoveries generally between 70 and 120%, particularly in complex environmental matrices where matrix-induced signal enhancement may occur, and relative standard deviations are below 10–15%. These methods need comprehensive sample preparation and are vulnerable to matrix effects, which may result in quantitative uncertainty [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

FTIR is generally adopted for the characterization of microplastics due to its efficiency in identifying polymers in particles larger than 10–20 µm. The accuracy of this method in identification has been reported as 80–95% when validated among spectral libraries. Even though the FTIR method is limited in its sensitivity for trace-level organic contaminants and nanoplastics, it plays a major role in environmental forensic investigations, including rapid material classification and preliminary source differentiation. The non-destructive nature of this method makes it an important screening and evidentiary support tool in environmental forensic investigations [

33,

34,

35].

ICP–MS-based techniques demonstrate exceptional sensitivity (pg–ng L

−1) and high precision, typically expressed as relative standard deviation (%RSD < 5%) for elemental contaminants and metal-tagged micro- and nanoplastics. Advanced configurations such as single-particle ICP–MS enable particle size detection down to approximately 20–50 nm, supporting quantitative particle characterization in complex environmental matrices. Although ICP–MS does not provide direct molecular structural information, it plays a critical complementary role in environmental forensic investigations by enabling elemental fingerprinting, quantification of trace metal signatures, and discrimination of contamination sources based on elemental profiles. When integrated with molecular techniques such as GC–MS, LC–MS/MS or spectroscopic methods, ICP–MS significantly strengthens multi-line evidentiary frameworks required for defensible forensic source attribution [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) provides high isotopic precision (±0.1–0.5%) and plays a critical role in environmental forensics by enabling source discrimination based on isotopic signatures that are independent of concentration levels. This capability is particularly valuable for distinguishing anthropogenic versus natural sources, reconstructing contamination pathways, and identifying transformation processes such as biodegradation or mixing of sources. When applied through compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA), IRMS allows contaminants with similar chemical structures to be differentiated based on their isotopic fingerprints, thereby strengthening evidentiary reliability in regulatory and legal investigations. Despite these strengths, IRMS requires complex sample preparation, careful correction for isotope fractionation, and access to robust reference isotope databases. Its interpretation is also context-dependent, often necessitating integration with molecular and spatial data to avoid ambiguity. Nevertheless, when combined with chromatographic and geospatial evidence, IRMS represents one of the most powerful tools for defensible source attribution in environmental forensic investigations [

41,

42,

43].

Spatial tools such as remote sensing and GIS lack conventional analytical detection limits but offer valuable forensic insight by identifying contamination hotspots and transport pathways. Machine learning methods applied to non-target HRMS data have demonstrated classification accuracies exceeding 85–95%, enabling probabilistic source discrimination; however, their forensic reliability depends on model transparency and validation [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

A comparative summary of analytical performance parameters (e.g., sensitivity, accuracy, precision), forensic relevance, and the methodological limitations of the discussed techniques is provided in

Table 1.

No single analytical technique satisfies all forensic requirements. Integrated, multi-method approaches combining chemical, isotopic, spatial, and statistical evidence are essential for defensible environmental forensic investigations.

5. Strategies for Reducing Emerging Contaminants in Water

The presence of emerging contaminants, especially in water, shows a noticeable increase day by day. Employing sophisticated treatment techniques (membrane filtration, biofiltration, activated carbon adsorption, advanced oxidation process, etc.), executing regulatory measures, limiting sources, and creating public awareness are necessary to handle this condition. The discharge of contaminants into water bodies can be controlled by shifting to green and smart infrastructure (e.g., rain gardens), making suitable changes in agricultural practices, implementing pretreatment techniques in hospitals and industries, etc. The regulatory framework can be modified considering the present scenario, and implementing it well in features related to the discharge of wastewater, continuous assessment of the implemented measures, and executing extended producer responsibility for chemical pollutants can also help in bringing down the EC level. As the contaminants can be released from daily use of products like personal care products and pharmaceuticals, making the public aware of the implications of ECs and safe handling of these products can bring a major change in controlling the release of ECs [

58].

6. Conclusions

The present study highlights the significance of environmental forensic methods for the identification and analysis of emerging contaminants in water bodies. Techniques like GS-MS, LC-MS/MS, FTIR, ICP-MS, IRMS, remote sensing, and GIS and statistical and machine learning approaches improved the efficiency of identifying and tracing ECs and their sources with high precision and accuracy. The review also discussed different types of ECs, including pharmaceuticals and personal care products, PFAS, MPs, and NPs, and antibiotic genes and their sources (municipal and domestic waste streams, healthcare facilities, agricultural runoff and livestock wastes, commercial and industrial waste, urban runoff and stormwater, and recreational activities), along with EC remediation strategies. Future initiatives should seek to combine forensic tools with big data analysis and machine learning, broaden non-targeted screening libraries, and fortify regulatory systems, as accurate detection is still the basis for risk analysis and targeted remediation. Managing current and future water quality challenges in a sustainable and preventive way will depend on the development of real-time monitoring systems and multidisciplinary approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N.P.; methodology, G.N.P.; validation, G.P.; investigation, G.N.P.; resources, G.N.P., M.S.A.S. and G.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.N.P. and G.P.; writing—review and editing, M.S.A.S., A.J., D.I.N. and G.M.T.; supervision, M.S.A.S. and G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data or materials other than the manuscript were produced. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep gratitude to a world-renowned humanitarian, Mata Amritanandamayi Devi, popularly known as Amma. Her inspired mentorship facilitates unique opportunities for a seamless blend of personal integrity and spiritual development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors further declare that certain sections of the paper were prepared with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools for language generation and content optimization.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECs | Emerging Contaminants |

| PPCP | Pharmaceuticals And Personal Care Products |

| EDCs | Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals |

| MPs | Microplastics |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| PFAS | Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances |

| ARGs | Antibiotic Resistance Genes |

| WWTP | Waste Water Treatment Plant |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| RDSE | Rotating-Disk Sorptive Extraction |

| Py-GC/MS | Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PETE or PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| PMMA | Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| TED-GC/MS | Thermal Extraction-Desorption Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| SPE | Solid-Phase Extraction |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| SPM | Suspended Particulate Matter |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| IR | Infrared |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| HR-SF-ICP-MS | High-Resolution Sector Field Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| REEs | Rare Earth Metals |

| ICP-TOFMS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| IRMS | Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry |

| CSIA | Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| GIS | Geographical Information System |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| CA | Cluster Analysis |

| NN | Neural Network |

| RF | Random Forest |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbors |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| HRMS | High–Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

References

- Talreja, N.; Hegde, C.; Kumar, E.M.; Chavali, M. Emerging Environmental Contaminants: Sources, Consequences and Future Challenges. In Green Technologies for Industrial Contaminants; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 119–149. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Asiminicesei, D.M.; Fertu, D.I.; Gavrilescu, M. Occurrence and fate of emerging pollutants in water environment and options for their removal. Water 2021, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamalagowri, S.; Shanthi, N.; Manjunathan, J.; Kamaraj, M.; Manikandan, A.; Aravind, J. Techniques for the detection and quantification of emerging contaminants. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 8, 2191–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Shukla, P.; Giri, B.S.; Chowdhary, P.; Chandra, R.; Gupta, P.; Pandey, A. Prevalence and hazardous impact of pharmaceutical and personal care products and antibiotics in environment: A review on emerging contaminants. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abioye, O.P.; Ijah, U.J.J.; Aransiola, S.A.; Auta, S.H.; Ojeba, M.I. Bioremediation of toxic pesticides in soil using microbial products. In Mycoremediation and Environmental Sustainability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, M.U.; Nisar, B.; Yatoo, A.M.; Sehar, N.; Tomar, R.; Tariq, L.; Ali, S.; Ali, A.; Rashid, S.M.; Ahmad, S.B.; et al. After effects of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) on the biosphere and their counteractive ways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 342, 126921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C.; La Merrill, M.A.; Patisaul, H.; Sargis, R.M. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health; The Endocrine Society and IPEN: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, A.C.; Crews, D.; Doan, L.L.; La Merrill, M.; Patisaul, H.; Zota, A. Introduction to Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs). In A Guide for Public Interest Organizations and Policy-Makers; The Endocrine Society and IPEN: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sakkiah, S.; Guo, W.; Pan, B.; Kusko, R.; Tong, W.; Hong, H. Computational prediction models for assessing endocrine disrupting potential of chemicals. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2018, 36, 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.M.; Yesodharan, G.; Arun, K.; Prasad, G. Unveiling the factors influencing groundwater resources in a coastal environment-a review. Agron. Res. 2023, 21, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, N.P.; Prasad, G.; Prabhakaran, V.; Priya, V. Understanding the impact of microplastic contamination on soil quality and eco-toxicological risks in horticulture: A comprehensive review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Addey, C.I.; Oderinde, O.; Okoro, J.O.; Uwamungu, J.Y.; Ikechukwu, C.K.; Okeke, E.S.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Odii, E.C. Toxic chemicals and persistent organic pollutants associated with micro-and nanoplastics pollution. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 11, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.; Ramesh, M.V.; Thomas, G.M. Changing profile of natural organic matter in groundwater of a Ramsar site in Kerala implications for sustainability. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, D.; Pearson, T.W. The social life of the “forever chemical”: PFAS pollution legacies and toxic events. Environ. Soc. 2021, 12, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Xiao, F.; Shen, C.; Chen, J.; Park, C.M.; Sun, Y.; Flury, M.; Wang, D. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in subsurface environments: Occurrence, fate, transport, and research prospect. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, M.; Corrà, F.; Bellio, M.; Guidolin, L.; Tallandini, L.; Irato, P.; Santovito, G. PFAS environmental pollution and antioxidant responses: An overview of the impact on human field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Z.; Zeng, L.; Xu, T.; Sun, S.; Yan, S.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y.; Jia, J.; Dou, T. Antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria: Occurrence, spread, and control. J. Basic Microbiol. 2021, 61, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Mohapatra, S.; Zhang, J.; Tran, N.H.; You, L.; He, Y.; Gin, K.Y.H. Source, fate, transport and modelling of selected emerging contaminants in the aquatic environment: Current status and future perspectives. Water Res. 2022, 217, 118418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayabil, H.K.; Teshome, F.T.; Li, Y.C. Emerging contaminants in soil and water. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 873499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Chaitali, R.O.Y.; Sinha, S.K. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS): A comprehensive review of synergistic combinations and their applications in the past two decades. J. Anal. Sci. Appl. Biotechnol. 2023, 5, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, G.; Mamane, H.; Ramesh, M.V. Geogenic and anthropogenic contamination of groundwater in a fragile eco-friendly region of southern Kerala, India. Agron. Res. 2022, 20, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arismendi, D.; Becerra-Herrera, M.; Cerrato, I.; Richter, P. Simultaneous determination of multiresidue and multiclass emerging contaminants in waters by rotating-disk sorptive extraction–derivatization-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Talanta 2019, 201, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.; Lennard, C.; Kingsland, G.; Johnstone, P.; Symons, A.; Wythes, L.; Fewtrell, J.; O’brien, D.; Spikmans, V. Rapid on-site identification of hazardous organic compounds at fire scenes using person-portable gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)–part 2: Water sampling and analysis. Forensic Sci. Res. 2020, 5, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, P.; Singh, A.; Chandra, R.; Kumar, P.S.; Raj, A.; Bharagava, R.N. Detection and identification of hazardous organic pollutants from distillery wastewater by GC-MS analysis and its phytotoxicity and genotoxicity evaluation by using Allium cepa and Cicer arietinum L. Chemosphere 2022, 297, 134123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ou, Q.; Jiao, M.; Liu, G.; Van Der Hoek, J.P. Identification and quantification of nanoplastics in surface water and groundwater by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 4988–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorolla-Rosario, D.; Llorca-Porcel, J.; Pérez-Martínez, M.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Bueno-López, A. Microplastics’ analysis in water: Easy handling of samples by a new Thermal Extraction Desorption-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (TED-GC/MS) methodology. Talanta 2023, 253, 123829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoffo, E.D.; Thomas, K.V. Quantitative analysis of nanoplastics in environmental and potable waters by pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 464, 133013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, M.E.; El-Nouby, M.A.; Kimani, P.K.; Lim, L.W.; Rabea, E.I. A review of the modern principles and applications of solid-phase extraction techniques in chromatographic analysis. Anal. Sci. 2022, 38, 1457–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.; Tavazzi, S.; Mariani, G.; Suurkuusk, G.; Paracchini, B.; Umlauf, G. Analysis of emerging organic contaminants in water, fish and suspended particulate matter (SPM) in the Joint Danube Survey using solid-phase extraction followed by UHPLC-MS-MS and GC–MS analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, R.; Song, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, S. Determination of pesticides and their degradation products in water samples by solid-phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2019, 149, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yao, B.; Yan, S.; Song, W. Determination of trace organic contaminants by a novel mixed-mode online solid-phase extraction coupled to liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, A.; Kozma, B.; Urbányi, B. Challenges and analytical strategies for monitoring emerging contaminants in aquatic environments: Focus on LC–MS methods. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, K.O.; Foster, H.A.; Routledge, E.J.; Scrimshaw, M.D. A comparison of different approaches for characterizing microplastics in selected personal care products. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2022, 41, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukotaka, A.; Kataoka, T.; Nihei, Y. Rapid analytical method for characterization and quantification of microplastics in tap water using a Fourier-transform infrared microscope. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148231. [Google Scholar]

- Maxson, C.; Tibby, J.; Marshall, J.; Kent, M.; Tyler, J.; Barr, C.; McGregor, G.; Cadd, H.; Schulz, C.; Lomax, B.H. Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy as a tracer of organic matter sources in lake sediments. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 581, 110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, I.; Vassileva, E. Method validation for high resolution sector field inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry determination of the emerging contaminants in the open ocean: Rare earth elements as a case study. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2017, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakanupongkul, A.; Sirisinha, K.; Saenmuangchin, R.; Siripinyanond, A. Analysis of microplastic particles by using single particle inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderach, T.; Gundlach-Graham, A.; Günther, D. Determination of carbon in microplastics and single cells by total consumption microdroplet ICP-TOFMS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 416, 2773–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, L.; Mitrano, D.M. Direct Measurement of Microplastics by Carbon Detection via Single Particle ICP-TOFMS in Complex Aqueous Suspensions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7263–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, J.; Gonzalez, G.; Menta, M.; Jimenez-Lamana, J.; Bouyssiere, B. Biogenic RH-SiO2 Nanoparticles for Vanadium Removal from Asphaltenes via GPC-ICP MS and spICP MS Analysis. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 12696–12703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, T.H.R.; do Rosário Zucchi, M.; Lemaire, T.J.; de Azevedo, A.E.G.; Viola, D.N. A statistical analysis of IRMS and CRDS methods in isotopic ratios of 2H/1H and 18O/16O in water. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślósarczyk, K.; Jakóbczyk-Karpierz, S.; Witkowski, A.J. Identification of water contamination sources using hydrochemical and isotopic studies—The Kozłowa Góra reservoir catchment area (Southern Poland). Water 2022, 14, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, E.J.; Yun, H.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Shin, K.H. Application of compound-specific isotope analysis in environmental forensic and strategic management avenue for pesticide residues. Molecules 2021, 26, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadas, M.; Samantaray, A.K. Applications of remote sensing and GIS in water quality monitoring and remediation: A state-of-the-art review. In Water Remediation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedhar, R.; Prasad, G. Groundwater potential change assessment using remote sensing and GIS: A case study of Ernakulam district. In Proceedings of the Advanced Technologies in Chemical, Construction and Mechanical Sciences: Icatchcome 2022, Coimbatore, India, 24–25 March 2022; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Martins, R.J.; Jang, J.; Badloe, T.; Khadir, S.; Jung, H.-Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Genevet, P.; Rho, J. Nanophotonics for light detection and ranging technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, K.S.; Sneha, M.L.; Aiswarya, S.; Anand, A.B.; Prasad, G.; Jayadev, A. Unlocking hidden water resources: Mapping groundwater potential zones using GIS and remote sensing in Kerala, India. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Technologies in Civil and Environmental Engineering (ICSTCE 2023), Pune, India, 15–16 June 2023; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2023; Volume 405, p. 04021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cüce, H.; Kalıpcı, E.; Ustaoğlu, F.; Kaynar, I.; Baser, V.; Türkmen, M. Multivariate statistical methods and GIS based evaluation of the health risk potential and water quality due to arsenic pollution in the Kızılırmak River. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2022, 37, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeed, M.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Karim, M.R.; Uddin, M.F.; Hasan, M.; Khan, R.H. Surface water quality profiling using the water quality index, pollution index and statistical methods: A critical review. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 18, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Keshari, A.K. Pattern recognition of water quality variance in Yamuna River (India) using hierarchical agglomerative cluster and principal component analyses. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkinahamira, F.; Feng, A.; Zhang, L.; Rong, H.; Ndagijimana, P.; Guo, D.; Cui, B.; Zhang, H. Machine learning approaches for monitoring environmental metal pollutants: Recent advances in source apportionment, detection, quantification, and risk assessment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; German-Labaume, C.; Mathiot, S.; Goix, S.; Chamaret, P. Using Bayesian networks for environmental health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza-López, F.J.; Rodríguez-Pascual, A.; Lopez-Pellicer, F.J.; Vilches-Blázquez, L.M.; Villar-Iglesias, A.; Masó, J.; Díaz-Díaz, E.; Ureña-Cámara, M.A.; González-Yanes, A. An analysis of existing production frameworks for statistical and geographic information: Synergies, gaps and integration. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Song, C.; Dubinsky, E.A.; Stewart, J.R. Tracking major sources of water contamination using machine learning. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 616692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; You, L.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Gin, K.Y.H. Advancing prediction of emerging contaminants in a tropical reservoir with general water quality indicators based on a hybrid process and data-driven approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila-Santiago, E.; Shi, C.; Mahadwar, G.; Medeghini, B.; Insinga, L.; Hutchinson, R.; Good, S.; Jones, G.D. Machine learning applications for chemical fingerprinting and environmental source tracking using non-target chemical data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 4080–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.K.; Chadha, M.; Rapp-Wright, H.; Mills, G.A.; Fones, G.R.; Gravell, A.; Stürzenbaum, S.; Cowan, D.A.; Neep, D.J.; Barron, L.P. Rapid direct analysis of river water and machine learning assisted suspect screening of emerging contaminants in passive sampler extracts. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.B.; Maillard, J.Y.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Emerging contaminants affect the microbiome of water systems—Strategies for their mitigation. npj Clean Water 2020, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |