Sex Estimation from Fragmented Thai Femora: Developing Segment-Specific Models Using Discriminant Function Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Measurements and Metric Analyses

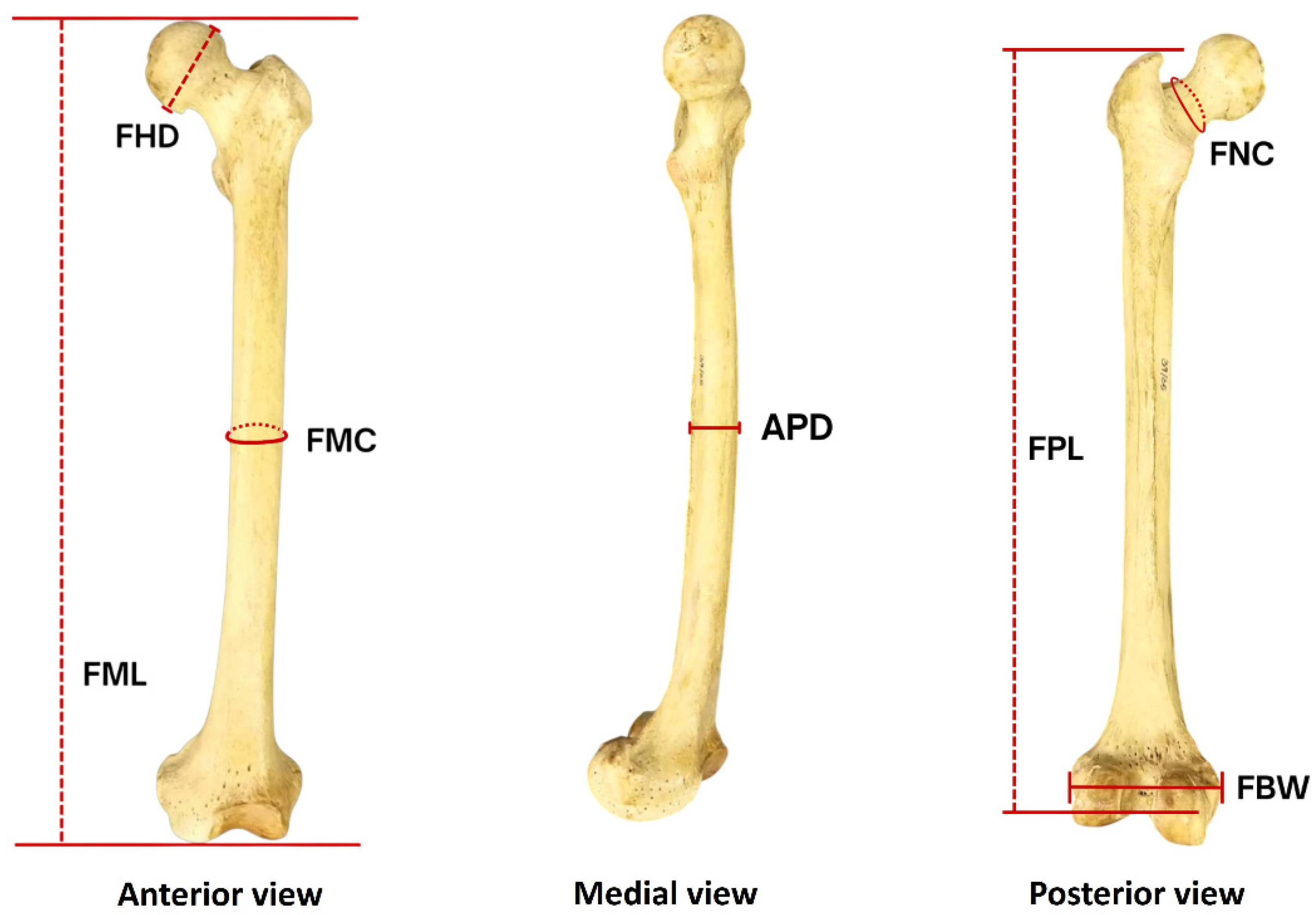

- Femur maximum length (FML) was measured as the greatest distance from the most superior point of the femoral head to the most inferior point of the condyle.

- Femur physiological length (FPL) represented the distance from the most superior point of the femoral greater trochanter to the inferior margin of the intercondylar notch.

- Femur weight (FW) was measured using a digital precision scale.

- Anteroposterior midshaft diameter (APD) was recorded as the maximum anteroposterior diameter at the femoral midpoint.

- Femoral midshaft circumference (FMC) was obtained at the midpoint location using a flexible measuring tape.

- Femoral vertical head diameter (FHD) was defined as the maximum superior–inferior diameter of the femoral head measured with digital calipers.

- Femoral neck circumference (FNC) was measured at the narrowest point of the femoral neck using a flexible measuring tape.

- Femoral bicondylar width (FBW) represented the maximum mediolateral distance across both condyles measured with the posterior condylar surfaces.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Reliability

3.2. Sexual Dimorphism

3.3. Discriminant Function Analysis for Sex Estimation

3.3.1. Discriminant Function Statistics

3.3.2. Classification Accuracy Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitation of Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Austin, D.; King, R.E. The Biological Profile of Unidentified Human Remains in a Forensic Context. Acad. Forensic Pathol. 2016, 6, 370–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoufi, N.; Bertsatos, A.; Chovalopoulou, M.E.; Villa, C. Forensic sex estimation using the vertebrae: An evaluation on two European populations. Int. J. Legal Med. 2020, 134, 2307–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakici, R.S.; Ayvat Ocal, Z.; Meral, O.; Oner, Z.; Oner, S. Estimation of sex from femoral bone using radiological imaging methods in Turkish population. Anthropol. Anz. 2024, 81, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monum, T.; Prasitwattanseree, S.; Das, S.; Siriphimolwat, P.; Mahakkanukrauh, P. Sex estimation by femur in modern Thai population. Clin. Ter. 2017, 168, e203–e207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curate, F.; Umbelino, C.; Perinha, A.; Nogueira, C.; Silva, A.M.; Cunha, E. Sex determination from the femur in Portuguese populations with classical and machine-learning classifiers. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2017, 52, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujaddughe, O.M.; Haberfeld, J.; Bidmos, M.A.; Olateju, O.I. Evaluation of standards for sex estimation using measurements obtained from reconstructed computed tomography images of the femur of contemporary Black South Africans. Int. J. Legal Med. 2025, 139, 1409–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonthai, W.; Poodendaen, C.; Kamwong, J.; Sangchang, P.; Duangchit, S.; Iamsaard, S. Sex and stature estimations from dry femurs of Northeastern Thais: Using a logistic and linear regression approach. Transl. Res. Anat. 2025, 38, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhoem, S.; Domett, K. Sex estimation by discriminant function analysis of long bones in prehistoric Southeast Asian populations. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2024, 35, e3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, D.; Krishan, K.; Kanchan, T. A methodological comparison of discriminant function analysis and binary logistic regression for estimating sex in forensic research and case-work. Med. Sci. Law. 2022, 63, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzullin, M.C.; Curate, F.; Freire, A.R.; Costa, S.T.; Prado, F.B.; Júnior, E.D.; Cunha, E.; Rossi, A.C. Validation of anthropological measures of the human femur for sex estimation in Brazilians. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 54, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Poodendaen, C.; Choompoo, N.; Namvongsakool, P.; Linlad, S.; Chalermrerm, J.; Duangchit, S.; Boonthai, W.; Iamsaard, S.; Aorachon, P.; Putiwat, P. External validation of femoral sex estimation equations: Evidence supporting population-specific standards in forensic anthropology. Transl. Res. Anat. 2025, 41, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavel, A.; Franklin, D. Counting human bone fragments using landmarks: Camposanto case study. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 56, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.M.; Hefner, J.T.; Smith, M.A.; Webb, J.B.; Bottrell, M.C.; Fenton, T.W. Forensic Fractography of Bone: A New Approach to Skeletal Trauma Analysis. Forensic Anthropol. 2018, 1, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indra, L.; Errickson, D.; Young, A.N.; Lösch, S. Uncovering Forensic Taphonomic Agents: Animal Scavenging in the European Context. Biology 2022, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraitis, K.; Eliopoulos, C.; Spiliopoulou, C. Fracture Characteristics of Perimortem Trauma in Skeletal Material. Internet J. Biol. Anthropol. 2008, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ranaweera, L.; Cabral, E.; Dissanayake, D.M.R.M.; Lakshan, W.S.V. Estimation of Sex from the Osteometric Measurements of the Femur in a Contemporary Sri Lankan Population. Int. J. Morphol. 2022, 40, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, J. A method for estimating sex using the clavicle, humerus, radius, and ulna. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.S. In the context of forensic casework, are there meaningful metrics of the degree of calibration? Forensic Sci. Int. Synerg. 2021, 3, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Hembram, P.; Roy, K.; Mukherjee, S.; Bhandari, R.; Kundu, S. Reconstructions of Length of Radius From its Fragments- A Pilot Study in Eastern Indian Population. J. Indian Acad. Forensic Med. 2023, 45, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfsdotter, C. Forensic archaeology and forensic anthropology within Swedish law enforcement: Current state and suggestions for future developments. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2021, 3, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubelaker, D.H.; Wu, Y. Fragment analysis in forensic anthropology. Forensic Sci. Res. 2020, 5, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelas González, N.; Rascón Pérez, J.; Chamero, B.; Cambra-Moo, O.; González Martín, A. Geometric morphometrics reveals restrictions on the shape of the female os coxae. J. Anat. 2017, 230, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiaffo, V.; Feitosa de Albuquerque, P.P.; Virginio de Albuquerque, P.; Duarte Ribeiro de Oliveira, B. Sexual Diagnosis Through Morphometric Evaluation of the Proximal Femur. Int. J. Morphol. 2019, 37, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Pivec, R.; Issa, K.; Kapadia, B.H.; Khanuja, H.S.; Mont, M.A. Large-diameter femoral heads in total hip arthroplasty: An evidence-based review. Am. J. Orthop. 2014, 43, 506–512. [Google Scholar]

- Cridlin, S. Piecewise Regression Analysis of Secular Change in the Maximum Femoral Vertical Head Diameter of American White Males and Females. Hum. Biol. 2016, 88, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeroy, E.; Mushrif-Tripathy, V.; Kulkarni, B.; Kinra, S.; Stock, J.T.; Cole, T.J.; Shirley, M.K.; Wells, J.C.K. Estimating body mass and composition from proximal femur dimensions using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 2167–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, C.; Holt, B.; Trinkaus, E. Who’s afraid of the big bad Wolff?: “Wolff’s law” and bone functional adaptation. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2006, 129, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Karki, R.K.; Palikhe, A.K.; Menezes, R.G. Sex Determination From the Bicondylar Width of the Femur: A Nepalese Study Using Digital X-ray Images. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2016, 55, 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.-G.; Yang, D.-Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhuo, T.-J.; Zhang, H.-C.; Xiang, J.; Wang, H.-F.; Ou, P.-Z.; Liu, J.-L.; Xu, L.; et al. Age-Related Bone Mineral Density, Bone Loss Rate, Prevalence of Osteoporosis, and Reference Database of Women at Multiple Centers in China. J. Clin. Densitom. 2007, 10, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Monroe, D.G. Regulation of Bone Metabolism by Sex Steroids. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a031211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Laurent, M.R.; Dubois, V.; Claessens, F.; O’Brien, C.A.; Bouillon, R.; Vanderschueren, D.; Manolagas, S.C. Estrogens and Androgens in Skeletal Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 135–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubelaker, D.H.; Khosrowshahi, H. Estimation of age in forensic anthropology: Historical perspective and recent methodological advances. Forensic Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpan, K.E.; Vadala, J.; Dhanaliwala, A.; Chao, T. Utilizing augmented reality for reconstruction of fractured, fragmented and damaged craniofacial remains in forensic anthropology. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 357, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankova, R. Anthropological analysis of human skeletal remains in forensic cases. J. Morphol. Sci. 2024, 7, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, K.L.; Janssen, M.C.L.; Stull, K.E.; van Rijn, R.R.; Oostra, R.J.; de Boer, H.H.; van der Merwe, A.E. Dutch population specific sex estimation formulae using the proximal femur. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 286, 268.e1–268.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvallo, D.; Retamal, R. Sex estimation using the proximal end of the femur on a modern Chilean sample. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alunni-Perret, V.; Staccini, P.; Quatrehomme, G. Sex determination from the distal part of the femur in a French contemporary population. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 175, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curate, F.; Coelho, J.; Gonçalves, D.; Coelho, C.; Ferreira, M.T.; Navega, D.; Cunha, E. A method for sex estimation using the proximal femur. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 266, 579.e1–579.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, J.; Cieślik, A.I.; Danel, D.P. Sex estimation using measurements of the proximal femur in a historical population from Poland. Anthropol. Rev. 2023, 86, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero, A.; Salicrú, M.; Turbón, D. Sex prediction from the femur and hip bone using a sample of CT images from a Spanish population. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 129, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P.; Ponsaillé, J.; Alunni-Perret, V.; Quatrehomme, G. A comparison between neural network and other metric methods to determine sex from the upper femur in a modern French population. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 192, 127.e1–127.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, J.; Eklics, G.; Tuck, A. A metric method for sex determination using the proximal femur and fragmentary hipbone. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Intra | Inter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM (mm) | rTEM (%) | R | TEM (mm) | rTEM (%) | R | |

| FML | 2.00 | 0.48 | 0.993 | 2.03 | 0.48 | 0.993 |

| FPL | 1.17 | 0.29 | 0.997 | 2.25 | 0.57 | 0.990 |

| APD | 0.22 | 0.80 | 0.994 | 0.53 | 1.92 | 0.963 |

| FMC | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.997 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 0.984 |

| FHD | 0.23 | 0.55 | 0.996 | 1.20 | 2.83 | 0.886 |

| FNC | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.997 | 1.34 | 1.43 | 0.973 |

| FBW | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.998 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.987 |

| Parameter | Male | Female | % Diff | t-Score | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| FML (mm) | 433.61 | 21.18 | 405.35 | 19.21 | 6.97 | 16.54 | <0.01 * |

| FPL (mm) | 408.39 | 19.54 | 383.26 | 18.78 | 6.56 | 15.51 | <0.01 * |

| FW (g) | 336.05 | 62.89 | 236.19 | 46.64 | 42.27 | 21.34 | <0.01 * |

| APD (mm) | 29.05 | 2.40 | 25.95 | 2.05 | 11.95 | 16.46 | <0.01 * |

| FMC (mm) | 87.29 | 5.73 | 79.51 | 5.15 | 9.78 | 16.90 | <0.01 * |

| FHD (mm) | 45.08 | 2.47 | 40.00 | 2.22 | 12.70 | 25.49 | <0.01 * |

| FNC (mm) | 99.76 | 6.21 | 88.23 | 5.34 | 13.07 | 23.54 | <0.01 * |

| FBW (mm) | 80.72 | 3.87 | 72.31 | 3.49 | 11.63 | 26.84 | <0.01 * |

| Analysis Method | Canonical R | Eigenvalue | Wilks’ Lambda | Chi-Square | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete analyses | ||||||

| Direct entry | 0.790 | 1.657 | 0.376 | 532.661 | 8 | <0.01 |

| Stepwise | 0.787 | 1.626 | 0.381 | 528.019 | 4 | <0.01 |

| Segment analyses | ||||||

| Proximal | 0.747 | 1.266 | 0.441 | 453.205 | 2 | <0.01 |

| Diaphyseal | 0.590 | 0.534 | 0.652 | 238.417 | 2 | <0.01 |

| Distal | 0.752 | 1.305 | 0.434 | 460.464 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Combined analyses | ||||||

| Prox. + Dia. | 0.752 | 1.300 | 0.435 | 460.617 | 4 | <0.01 |

| Prox. + Dis. | 0.771 | 1.470 | 0.405 | 494.951 | 3 | <0.01 |

| Dia. + Dis. | 0.754 | 1.319 | 0.431 | 463.107 | 3 | <0.01 |

| Analysis Method | Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | Group Centroids | Original Accuracy (%) | Cross-Validated Accuracy (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Overall | Male | Female | Overall | ||||

| Complete analyses | |||||||||

| Direct entry | FML | −0.015 | M: 1.278 | 90.36 | 92.86 | 91.61 | 90.00 | 92.50 | 91.25 |

| FPL | 0.010 | F: −1.292 | |||||||

| APD | 0.047 | ||||||||

| FMC | −0.043 | ||||||||

| FW | 0.008 | ||||||||

| FHD | 0.097 | ||||||||

| FBW | 0.134 | ||||||||

| FNC | 0.046 | ||||||||

| (Constant) | −16.134 | ||||||||

| Stepwise | FMC | −0.030 | M: 1.266 | 89.29 | 93.21 | 91.25 | 88.93 | 92.00 | 90.47 |

| FW | 0.008 | F: −1.280 | |||||||

| FBW | 0.151 | ||||||||

| FNC | 0.062 | ||||||||

| (Constant) | −17.232 | ||||||||

| Segment analyses | |||||||||

| Proximal | FHD | 0.289 | M: 1.121 | 88.57 | 90.71 | 89.64 | 88.57 | 90.71 | 89.64 |

| FNC | 0.068 | F: −1.125 | |||||||

| (Constant) | −18.693 | ||||||||

| Diaphyseal | APD | 0.187 | M: 0.730 | 80.00 | 82.14 | 81.07 | 80.00 | 81.76 | 80.88 |

| FMC | 0.113 | F: −0.730 | |||||||

| (Constant) | −14.564 | ||||||||

| Distal | FBW | 0.271 | M: 1.136 | 86.07 | 87.14 | 86.61 | 85.36 | 87.14 | 86.25 |

| (Constant) | −20.744 | F: −1.144 | |||||||

| Combined analyses | |||||||||

| Prox. + Dia. | APD | 0.052 | M: 1.136 | 89.64 | 91.79 | 90.72 | 89.64 | 91.43 | 90.54 |

| FMC | 0.014 | F: −1.140 | |||||||

| FHD | 0.249 | ||||||||

| FNC | 0.064 | ||||||||

| (Constant) | −19.283 | ||||||||

| Prox. + Dis. | FHD | 0.121 | M: 1.203 | 88.57 | 91.79 | 90.18 | 88.57 | 91.42 | 90.00 |

| FNC | 0.044 | F: −1.217 | |||||||

| FBW | 0.154 | ||||||||

| (Constant) | −21.092 | ||||||||

| Dia. + Dis. | FBW | 0.258 | M: 1.142 | 88.21 | 88.57 | 88.39 | 87.14 | 88.21 | 87.68 |

| APD | 0.083 | F: −1.151 | |||||||

| FMC | −0.017 | ||||||||

| (Constant) | −20.585 | ||||||||

| Author (Year) | Population | No. of Samples | Segment Analysis | Method Analysis | Accuracy (%) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanese et al., 2008 [42] | American | N: 300 b | Proximal | LR | 89.4 |

| du Jardin et al., 2009 [41] | French | M: 38, F: 38 | Proximal | LR | 89.5 |

| DFA | 88.2 | ||||

| Neural network | 93.4 | ||||

| Clavero et al., 2015 [40] | Spanish | M: 56, F: 58 | Proximal | LR | 93.0 |

| Curate et al., 2016 [38] | Portuguese | M: 138, F: 114 | Proximal | LR | 85.7 |

| Colman et al., 2018 [35] | Dutch | M: 57, F: 57 | Proximal | LR | 90.0 |

| Carvallo & Retamal, 2020 [36] | Chilean | M: 100, F: 100 | Proximal | LR | 95.7 |

| Ranaweera et al., 2022 [16] | Sri Lankan | M: 48, F: 38 | Proximal | DFA and LR | 75.6 |

| Diaphyseal | 76.9 | ||||

| Distal | 70.5 | ||||

| Wysocka et al., 2023 [39] | Polish | M: 137, F: 115 | Proximal | DFA | 92.3 |

| Poodendaen et al. (This study) | Thai | M: 280, F: 280 | Proximal | DFA | 89.6 |

| Diaphyseal | 80.1 | ||||

| Distal | 86.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poodendaen, C.; Choompoo, N.; Srisen, K.; Linlad, S.; Chalermrerm, J.; Boonthai, W.; Iamsaard, S.; Tangsrisakda, N.; Arun, S.; Duangchit, S. Sex Estimation from Fragmented Thai Femora: Developing Segment-Specific Models Using Discriminant Function Analysis. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040069

Poodendaen C, Choompoo N, Srisen K, Linlad S, Chalermrerm J, Boonthai W, Iamsaard S, Tangsrisakda N, Arun S, Duangchit S. Sex Estimation from Fragmented Thai Femora: Developing Segment-Specific Models Using Discriminant Function Analysis. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040069

Chicago/Turabian StylePoodendaen, Chanasorn, Narawadee Choompoo, Kaemisa Srisen, Supapit Linlad, Jetniphat Chalermrerm, Worrawit Boonthai, Sitthichai Iamsaard, Nareelak Tangsrisakda, Supatcharee Arun, and Suthat Duangchit. 2025. "Sex Estimation from Fragmented Thai Femora: Developing Segment-Specific Models Using Discriminant Function Analysis" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040069

APA StylePoodendaen, C., Choompoo, N., Srisen, K., Linlad, S., Chalermrerm, J., Boonthai, W., Iamsaard, S., Tangsrisakda, N., Arun, S., & Duangchit, S. (2025). Sex Estimation from Fragmented Thai Femora: Developing Segment-Specific Models Using Discriminant Function Analysis. Forensic Sciences, 5(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040069