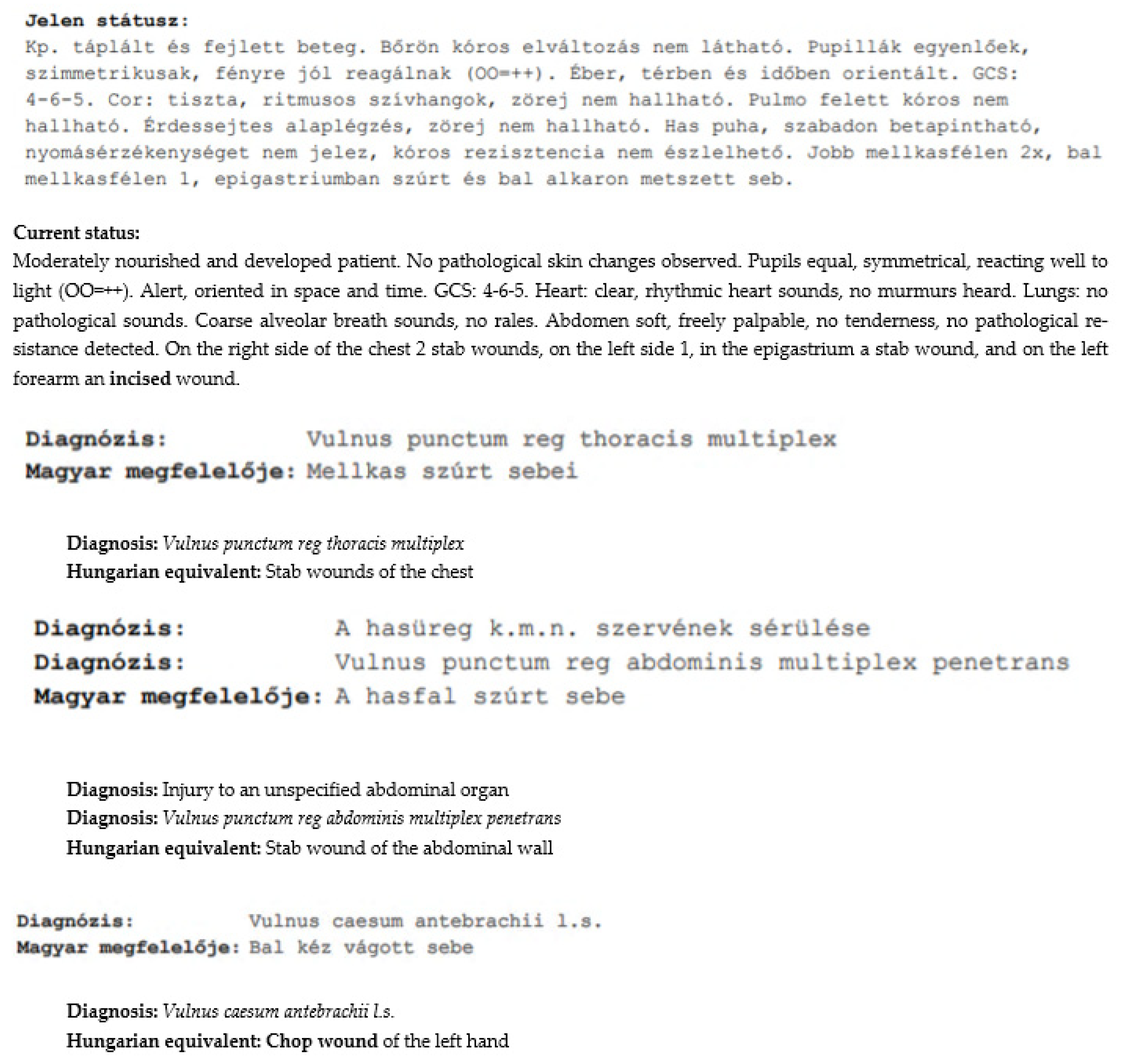

1. Introduction

Nonfatal interpersonal violence—including crimes such as rape, sexual assault, robbery, and both aggravated and simple assault—accounts for a large number of criminal acts with significant long-term physical, psychological, social, and economic consequences [

1,

2,

3]. Victims of nonfatal interpersonal violence are usually seen only in emergency departments or by other primary healthcare providers, as access to clinical forensic services is limited [

4]. Consequently, while in some countries victims of interpersonal violence are examined by trained forensic professionals, in most countries they are assessed solely by clinicians—many of whom are unaware of the existence of clinical forensic medicine [

5,

6]. As a result, any subsequent forensic assessment of the victims’ injuries must rely on the clinical documentation.

The documentation of injuries resulting from accidents or acts of violence serves a vital dual purpose in healthcare. Clinically, it supports diagnosis, guides treatment, and ensures continuity of care. Yet these same records are often reexamined—sometimes months later—as legal evidence in criminal proceedings. In emergency departments, this dual function presents a recurring challenge. Physicians must document injuries quickly under significant time constraints, often without structured protocols or templates to ensure forensic adequacy. While some guidelines exist for investigating specific groups of living victims of violence [

7,

8], there is no general, internationally accepted protocol for the examination of victims of interpersonal violence. Detailed information on injury types, characteristics, and documentation can be found in forensic pathology or forensic medicine texts [

9,

10,

11,

12], as well as in clinical forensic medicine manuals [

13]. However, these resources are unfamiliar to most clinicians. The lack of specific, context-adapted guidelines means that critical medico-legal details—such as wound morphology or anatomically precise terminology—are frequently underreported or inconsistently noted. These difficulties are further exacerbated during night shifts and periods of staff shortage, when patient volume remains high and clinical urgency often takes precedence over legal precision. In such settings, documentation may omit key details or rely on ambiguous wording, diminishing its forensic value. Clinicians without specialized training often underestimate the legal significance of such cases and typically lack the knowledge needed to properly document, collect, and preserve forensic evidence [

3,

14,

15]. This persistent disconnect between clinical recording practices and judicial expectations underscores the need for harmonized documentation tools, targeted training, and stronger interdisciplinary coordination in emergency medical care.

The divide between clinical and forensic perspectives on injury documentation is further deepened by divergent terminology, classification systems, and underlying objectives. In clinical settings, descriptions of trauma are typically shaped by their therapeutic implications—what matters most is how an injury affects treatment decisions. Forensic experts, in contrast, are concerned with reconstructing how the injury occurred, determining the force or instrument involved, and evaluating potential intent. These differing goals naturally give rise to inconsistencies in how injuries—especially soft tissue trauma such as abrasions, contusions, or different types of wounds—are characterized [

16,

17]. The situation is made more complex by the widespread use of broad diagnostic systems like the ICD, which often lack the granularity needed for forensic interpretation [

18].

This concern has clear practical implications. When clinical records omit precise descriptors or use ambiguous terminology, their effectiveness as forensic evidence is often compromised [

19]. Several studies have drawn attention to this problem: injury reports frequently lack the morphological detail needed for accurate forensic evaluation, particularly in cases involving soft tissue trauma [

20,

21,

22]. Other investigations have pointed to the routine use of vague language and the omission of key contextual information—such as injury size and exact anatomical location—in emergency medical documentation [

23,

24,

25].

These gaps in documentation directly hinder the forensic expert’s ability to determine how an injury occurred, assess its severity, or distinguish between accidental and inflicted harm. A comparative study of 546 clinical reports from Hungary, Austria, and Germany found that approximately 15–20% of the records in each country were either inadequate or entirely unsuitable for forensic interpretation [

26]. Even photographic evidence, when available, is often inadequately produced: images may lack standardized lighting, fail to include scale indicators, or be poorly framed—all of which diminishes their forensic value [

23,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Taken together, these findings point to a structural disconnect between routine clinical documentation practices and the rigorous evidentiary standards required in forensic contexts [

28].

The present study focuses primarily on soft tissue injuries, as these lesions tend to evolve over time, making their accurate documentation crucial—especially in cases where ideal photographic evidence prior to medical interventions like suturing is lacking. Without such visual records, reliably proving the original injury becomes extremely challenging [

26]. Previous research has also indicated that the clinical terminology used for bone injuries tends to be more consistent than that for soft tissue injuries [

31]. Furthermore, bone injuries can often be corroborated retrospectively through follow-up X-rays, which is generally not possible with soft tissue trauma.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, multidisciplinary study is based on a randomized sample of 1000 anonymized medical diagnostic reports of injuries, collected from several hospitals and clinics throughout Hungary between 2019 and 2025. The reports originated from the Clinical Center of the University of Debrecen (Department of Traumatology, 35 reports); the University of Pécs, Medical School (Department of Traumatology and Emergency Care, 198 reports); Zala County Hospital (Department of Traumatology, 33 reports); Szent Rafael Hospital in Nagykanizsa (Department of Traumatology, 106 reports); Semmelweis University in Budapest (Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 105 reports); Manninger Jenő Hospital in Budapest (105 reports); and Tolna County Balassa János Hospital and Outpatient Clinic in Szekszárd (418 reports). Ethical approval was granted by the Hungarian Scientific and Research Ethics Committee, under approval number IV/7235-4/2020/EKU, and all procedures followed national regulations on data protection and patient confidentiality. All patient data were fully anonymized before analysis. Relevant sections of each report were extracted and compiled using Microsoft Excel.

The samples were randomly selected from the documentation database of each institution by the traumatologist expert and subsequently anonymized. In cases with multiple reports, the final report was used, as it summarized all relevant findings for a criminal procedure. The inclusion criterion was that the medical report had been forwarded by the hospital for criminal investigation, while the exclusion criterion was that the case was still under processing and the report had not yet been sent to the prosecution. For cases with multiple injuries, all injuries mentioned in the morphological descriptions and diagnoses were considered. Laboratory findings or imaging results were analyzed only if they were referenced in the final diagnoses or the morphological injury description.

For the analysis, numeric codes were assigned to the following variables: main injury category (affected tissue); injury category in the description (based on underlying mechanisms); for soft tissue injuries, whether skin continuity was disrupted; affected body part and region; type of Hungarian diagnosis (ICD-10-based or individually phrased; accurate or ambiguous); related diagnosis in Latin (if provided); affected body part in the diagnosis; and the presence and linguistic realization of injury characteristics. Within the group of soft tissue injuries, an additional variable was introduced to distinguish between blunt- and sharp-force trauma. The coding was carried out manually—following the coding manual applied in the previous study [

15]—by the terminologist research team member and was reviewed by the traumatologist expert team member. As discrete variables were used, chi-squared tests were performed for univariate analyses, and logistic regression was applied for multivariate analysis to examine relationships between the variables.

To place the findings in a broader context, a manual review of relevant clinical and forensic literature was conducted. Additionally, the interpretation of findings and development of practical recommendations were carried out collaboratively by the interdisciplinary research team, which included both a practicing clinician and a forensic expert.

All data, protocols, and supporting materials will be made available upon reasonable request. No generative artificial intelligence tools were used in the design or analysis of the study, apart from minor assistance with formatting and grammar correction.

3. Results

In the 1000 clinical reports analyzed, a total of 3462 injuries were documented. Among these, 2266 injuries involved soft tissues, while 767 injuries affected the bones or teeth. An additional 429 cases were classified as other types of trauma, including concussions and other forms of neurological injury. Of the soft tissue injuries analyzed, 1085 affected the head and neck region, 405 involved the upper extremities, 354 were located on the lower extremities, 399 affected the trunk, and in 23 cases the affected body part was not recorded.

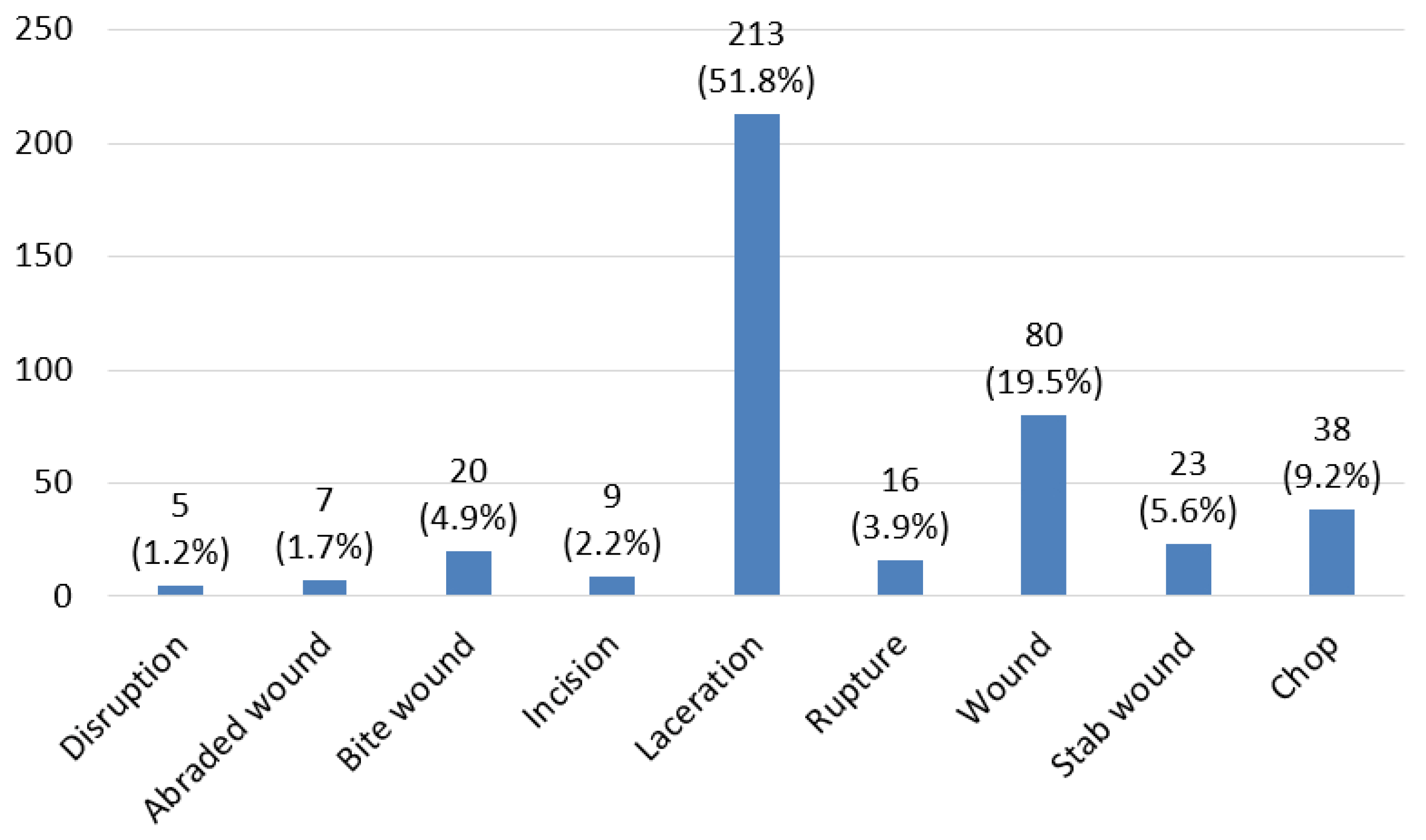

Among the 2266 soft tissue injuries, three categories were distinguished. Injuries involving disruption of skin continuity or material loss—referred to as “wounds,” such as incisions or lacerations in the injury descriptions—accounted for 411 cases, with nine injury types recorded (

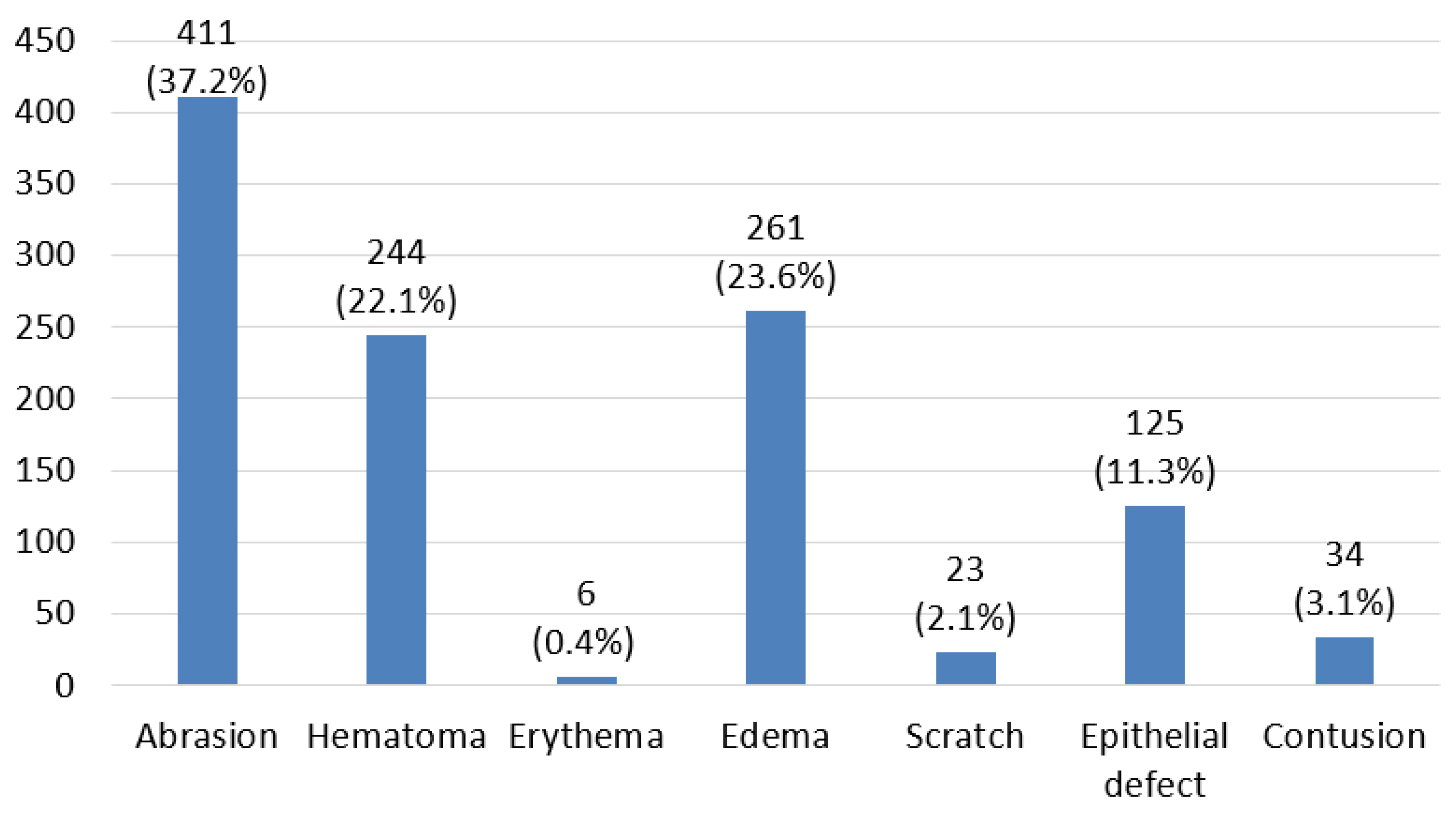

Figure 1). Injuries that did not involve disruption of skin continuity, such as hematomas, accounted for 1104 cases, with nine injury types recorded in the morphological descriptions (

Figure 2). A further 751 injuries could not be classified based on the descriptions provided, such as the term “injury” by itself. In 352 of these cases, the reports mentioned only subjective symptoms without referring to any additional morphological changes; typical examples include descriptions such as “painful” or “tenderness on pressure.” This third group also included cases in which vague terms such as “injury” or “trace of trauma” were used without further specification, or in which the entire injury description was missing.

3.1. The Level of Detail in Soft Tissue Injury Descriptions

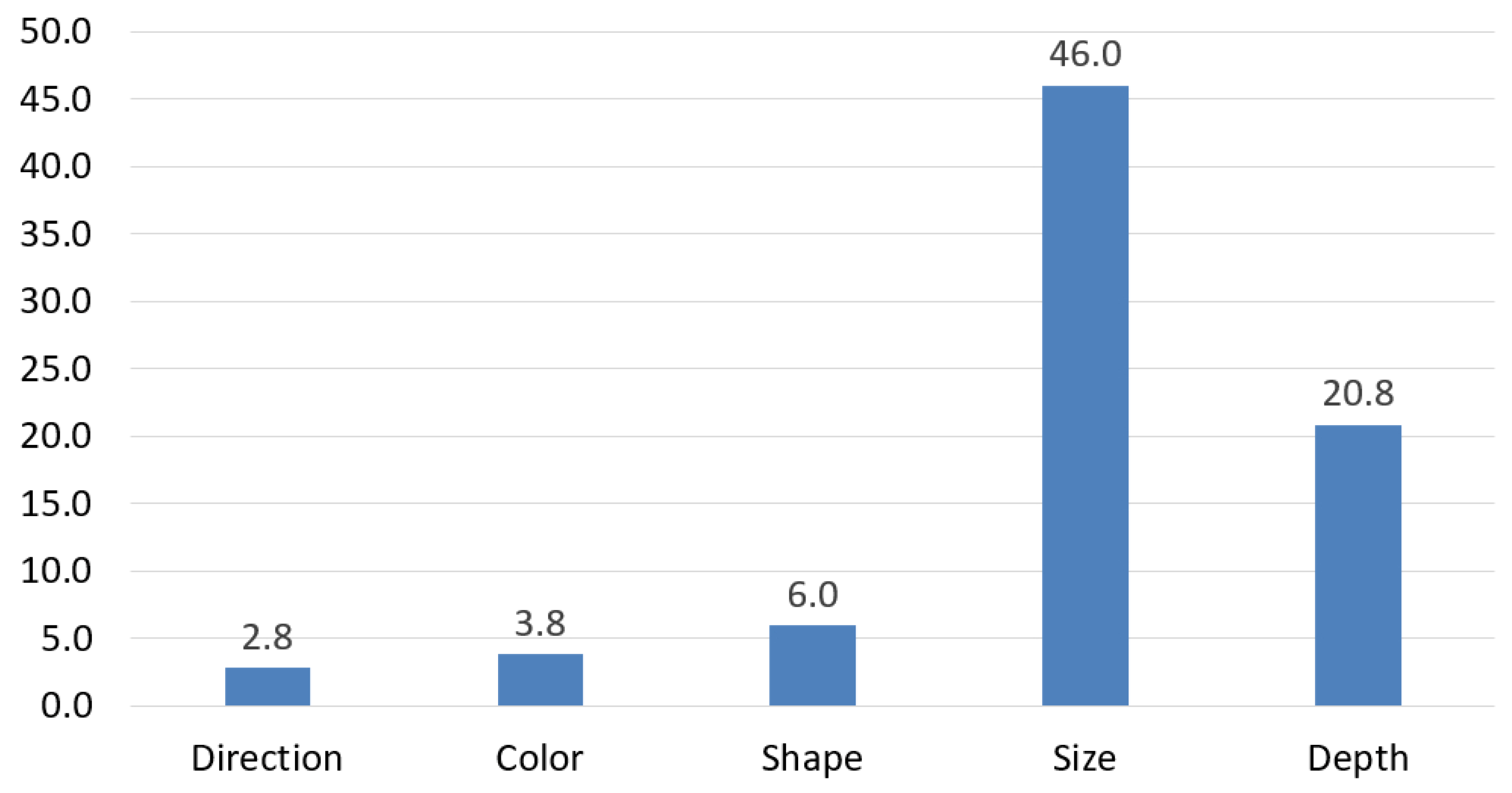

The level of detail in soft tissue injury descriptions was further assessed by examining how many specific injury characteristics were recorded on average per case. For injuries involving disruption of skin continuity or material loss—referred to as “wounds”—an average of only 1.70 characteristics were documented per injury, despite the range of possible descriptors such as size, depth, margins, wound walls, edges, condition of surrounding tissue, presence of tissue bridges, wound base, and the injury’s course or direction. Notably, many of these details were frequently omitted, and certain features, such as wound edges, were not mentioned in any report (

Figure 3). In contrast, injuries that did not involve skin continuity disruption—such as hematomas—were described with considerably less detail, averaging just 0.79 characteristics per injury. Typical descriptors in this group included color and age, shape, size, depth, and course or direction (

Figure 4), but these features were often inconsistently recorded across cases.

In 212 of the 2266 soft tissue injury descriptions, the number of injuries could not be interpreted, as vague descriptors such as “multiple” or “numerous” were used without specifying the exact number or even the extent of the affected area. Furthermore, in 134 cases, the depth of injuries was described using ambiguous terms such as “superficial” or “deep” without specifying the affected tissue layer or providing numeric probing data. This overall pattern reveals a general lack of thorough morphological documentation, especially for closed soft tissue injuries.

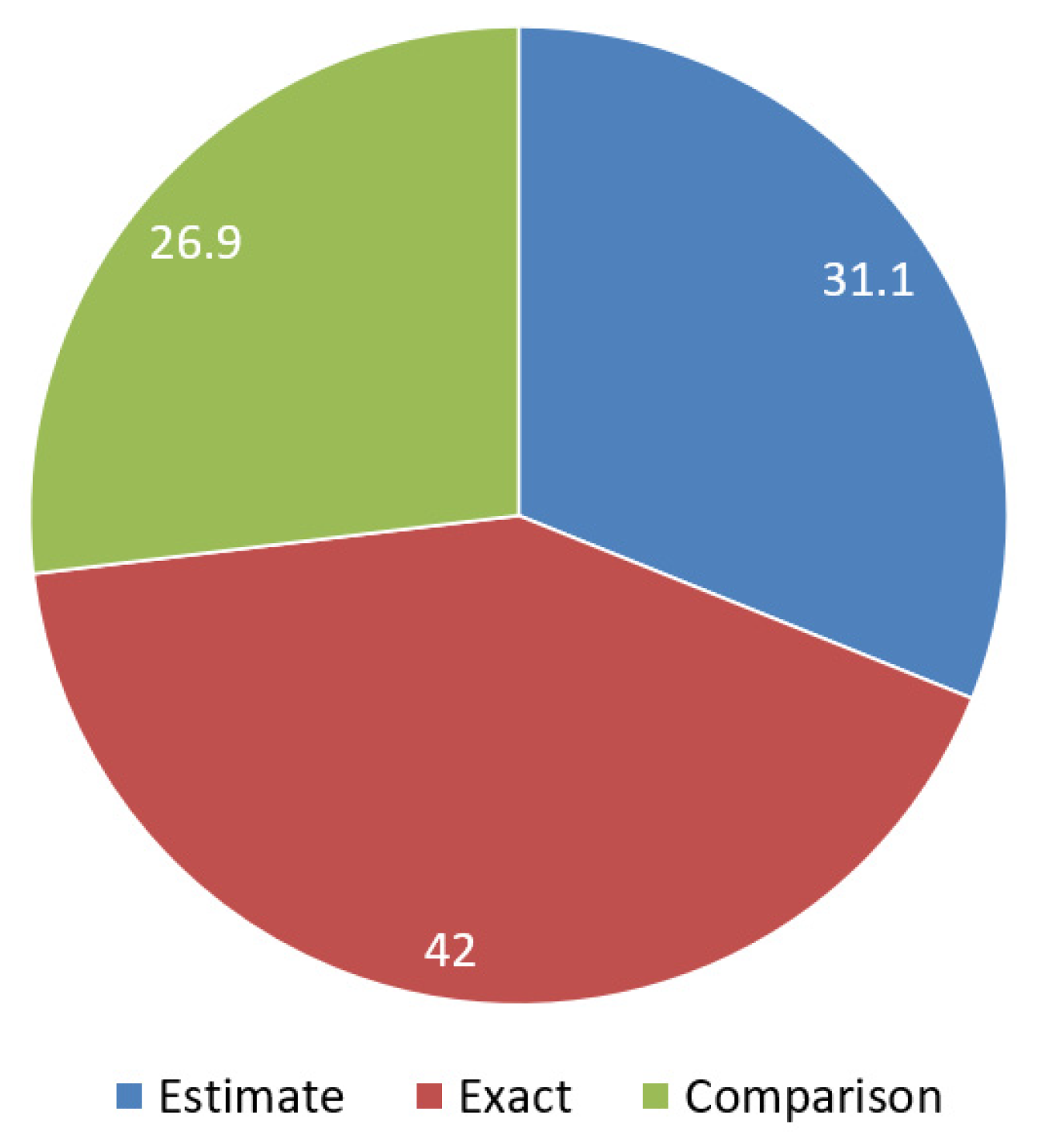

Size is also a fundamental morphological detail that should be recorded in descriptions of soft tissue injuries, yet the analysis revealed it was frequently omitted. Out of 2266 soft tissue injuries examined, size was completely missing in 1411 cases, meaning that over 62% of injury descriptions lacked this crucial information. When size was documented, three main patterns emerged. In 42% of cases, exact measurements were provided, typically using two dimensions expressed in millimeters or centimeters (e.g., “2 × 3 mm”). In 31.1% of cases, approximate sizes were noted with qualifiers such as “circa,” either as a single dimension (e.g., “approx. 3 cm long”) or two dimensions (e.g., “about 4 × 5 cm”). The remaining 26.9% of reports described injury size by comparing it to everyday objects—such as vegetables (nuts, almonds, apples), coins, body parts (fingertips, fingers, palms, fists), or small items (pinheads, needles)—instead of providing measurements (

Figure 5).

Logistic regression was performed to examine the relationship between the documentation of injury size and the variable affected body part in soft tissue injuries. Injury size was used as the dependent variable because, unlike all other characteristics, it is consistently associated with every type of soft tissue injury. Since injury types with disruption of skin continuity differ substantially from those without such disruption, all analyses were adjusted for this variable. The logistic regression model explained 23.1% of the variance in the outcome and correctly classified 72.4% of cases, with stronger performance for the reference group than for the target group. The analysis revealed that the documentation of injury size was strongly influenced by the affected body part (χ2 = 34.133, df = 3, p < 0.001). Compared to injuries of the head and neck, injuries affecting the trunk were significantly less likely to include size documentation (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.45–0.88, p = 0.007), and injuries in the upper extremities were even less likely (OR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.18–0.44, p < 0.001). No significant difference was found for the lower extremities. With respect to injury mechanisms, blunt-force injuries were significantly less often documented with a size (OR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.36–0.59, p < 0.001), while sharp-force injuries did not show a statistically significant effect.

3.2. Terminological Inconsistencies Related to Injuries Caused by Blunt-Force Trauma

The analysis of the corpus revealed notable inconsistencies and ambiguities in the terminology used to describe injuries resulting from blunt-force trauma. Two recurrent vague terms were observed: “zúzódás” (bruise) and “zúzott seb” (bruised wound) or “zúzott sérülés” (bruised injury).

The term zúzódás (bruise) appeared in 39 reports. Strikingly, in 34 of these cases—nearly the entire subset—fewer than two morphological characteristics were recorded, the most frequent one was size (n = 14). This suggests a widespread tendency to rely on the term itself as a sufficient description, rather than providing additional forensic-relevant details such as size, shape, color, or age of the lesion.

The second group of terms, zúzott seb (bruised wound) and zúzott sérülés (bruised injury), occurred in 49 reports. Of these, 26 cases included fewer than two injury characteristics, with size being the most frequently documented (n = 15), again indicating limited documentation. More importantly, this terminology presents a serious interpretive challenge. While zúzódás clearly refers to a closed soft tissue injury without skin disruption, the compound terms zúzott seb and zúzott sérülés are inherently ambiguous. In the absence of clear morphological detail, it remains unclear whether clinicians used the term seb (wound) or sérülés (injury) in a general medical sense meaning trauma without necessarily implying skin disruption, or in the forensic sense, where such terms typically indicate a breach of skin continuity or material loss. With only the dimension given, it is impossible to determine which injury type was actually observed by the physician. This terminological and descriptive vagueness was also reflected in the associated diagnoses: the vague terms zúzott sérülés or zúzott seb (bruised injury/wound) appeared 59 times; in 985 instances, the diagnosis noted zúzódás (bruise), with 194 of these cases providing no injury description.

In the case of superficial injuries typically resulting from blunt-force trauma, a similar terminological ambiguity was observed. The term horzsolás (abrasion) appeared frequently in the corpus, with 411 occurrences. However, the compound expressions horzsolt sérülés (abraded injury) and horzsolt seb (abraded wound) were also used seven times in total. While horzsolás clearly refers to a superficial lesion caused by a tangential force that scrapes away the superficial layers of the skin, the addition of sérülés (injury) or seb (wound) introduces interpretive uncertainty for the same reasons discussed above. The problem was further reflected in the related diagnoses: horzsolás (abrasion) was listed 113 times, while horzsolt seb or horzsolt sérülés (abraded wound/injury) appeared 22 times. In 15 of these latter cases, fewer than two morphological injury characteristics were documented, which made it difficult to verify the type and severity of injury. As with bruises and abrasions, the lack of consistent descriptors impairs both clinical clarity and forensic interpretability.

3.3. Terminological Inconsistencies Related to Injuries Caused by Sharp Force

A notable terminological problem was identified in the documentation of sharp-force injuries. The diagnostic term vágott seb (chop wound) appeared 28 times in the reports. However, in six of these cases, the corresponding morphological descriptions referred to injuries typically associated with blunt-force trauma, such as abrasions or lacerations. Only 18 cases clearly referred to a chop wound in both the diagnosis and the description. In two cases, while the diagnosis labeled the injury as a chop wound, the morphological descriptions referred to it as metszett sérülés (incised injury) or metszett seb (incised wound)—terms that denote injuries with a distinctly different mechanism and severity. In one case, szúrt seb (stab wound) was described, and in another case, seb (wound, without specification) was used, while vágott seb (chop wound) remained the diagnosis in both.

Out of these 28 cases diagnosed as chop wounds, the wound surroundings were described in 4 cases, the depth in 13 cases, and the size in 22 cases. In 8 cases (28.57% of all diagnosed chop wounds), the depth was described as superficial, which contradicts the typical forensic understanding of chop injuries as involving deeper tissue damage.

3.4. Use of International Diagnostic Classification Categories

The analysis revealed a reliance on international diagnostic classification (ICD-10) categories in place of detailed, descriptive diagnoses in 27.10% of 2266 soft tissue injuries. Of these, 50.72% concerned the head and neck region, 17.70% the upper extremities, 14.99% the trunk, and 14.83% the lower extremities. In 4.47% of all ICD-10 diagnoses no morphological description of the injury was provided.

From a terminological perspective, only 11.96% of the ICD-coded diagnoses were unambiguous, specifying the nature and characteristics of the injury clearly. Meanwhile, 67.30% of the diagnostic categories were overly general, using terms such as “superficial injury” or “wound” without further detail regarding the injury type, mechanism, affected body side or part, or the severity of the trauma. This lack of specificity reduces the interpretability of the documentation, especially in a forensic context where precise terminology is essential.

Chi-squared tests showed statistically significant differences between the affected body regions and the likelihood of relying on generalized ICD categories, indicating variation in documentation practices depending on the anatomical site of the injury. In the head and neck region, significantly more ICD diagnostic categories were used compared to the extremities (p < 0.001), and terminologically ambiguous categories were also more frequent in this region (22.12%) than in relation to the extremities (14.18%) and the trunk (2.10%). These findings highlight a concerning reliance on generalized ICD-10 categories in place of individualized, anatomically, and mechanistically precise diagnoses—particularly in the head and neck region, where the proximity to vital structures, high forensic relevance, and frequent involvement in abuse-related trauma make accurate diagnostic terminology especially critical.

4. Discussion

Concerns about the inadequate forensic-quality documentation of soft tissue injuries are echoed in international literature. Even when digital imaging tools are available, clinical and forensic records often fail to include the level of morphological detail needed for meaningful legal interpretation [

32]. Studies have also pointed out that inconsistencies in terminology and the limited use of standardized descriptors can complicate not only clinical decision-making but also the forensic reconstruction of the traumatic event [

23].

These results align with the present study, in which the number of recorded injury characteristics was found to be extremely low across all types of soft tissue injuries. Although the most frequently documented parameter was the size or dimension of the injury, even this detail was often recorded ambiguously. In approximately one-third of the cases, size was noted using vague approximations (e.g., “approx. 3 cm”) or non-standard comparisons to everyday objects such as a “palm” or an “apple,” which lack forensic precision. Our analysis showed that the documentation of injury size was influenced by both the body region and the injury mechanism. Injuries to the trunk and upper extremities, as well as blunt-force injuries, were less likely to include size information, while head, neck, and sharp-force injuries were better documented. These findings may also indicate that minor injuries, particularly those in less visible areas or resulting from blunt-force trauma, are more prone to underreporting, highlighting the need for careful and standardized documentation.

When previous investigations are considered, the shortcoming in documentation becomes even more apparent. In a study conducted over a decade ago on 339 Hungarian clinical reports, the average number of recorded characteristics per soft tissue injury was 0.87 [

26]. Similarly, a study examining Hungarian maxillofacial injury documentation reported an average of 0.64 descriptors per soft tissue injury [

31]. In the current study, if wounds and other soft tissue injury types are not considered separately, this number increases only slightly to 0.70. Studies from other countries also report similarly low rates of documenting wound characteristics [

20].

A key factor contributing to the inconsistencies observed in soft tissue injury documentation may lie in the terminological gap between clinical and forensic interpretations of trauma-related terms. In particular, the divergent usage of terms describing blunt-force trauma—especially those involving skin disruption—suggests fundamentally different conceptual frameworks. In Hungarian surgical literature, the term

zúzott seb (bruised wound) is typically defined as a contusion accompanied by a disruption of the skin’s continuity (

vulnus contusum) [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. “Bruise” as a distinct injury type (

contusio) is rarely addressed in these texts, likely because such injuries usually require no surgical intervention. In contrast, forensic literature offers a clearer distinction between a

bruise (

contusio)—a subcutaneous hemorrhage without a break in the skin—and a

laceration (

vulnus ruptum or

lacerocontusum), defined as a wound caused by blunt-force trauma that results in a discontinuity of the skin [

38,

39] (

Table A1). In our corpus, however, nearly all cases of

zúzódás (bruise) had fewer than two morphological characteristics recorded. This indicates a widespread tendency to rely on the term itself as a sufficient description, rather than providing additional forensic-relevant details such as the size, shape, color, or age of the lesion.

As Jason Payne-James emphasizes, “the word ‘wound’ requires evidence of a break in the continuity of the skin. A scratch is insufficient; there needs to be a breach in the whole of the skin” [

40]. Such definitional clarity is crucial in forensic practice, yet these distinctions are often blurred or overlooked in clinical documentation, which may contribute to misunderstandings in forensic interpretation. This terminological divergence may explain why clinicians occasionally apply terms such as

zúzott seb (bruised wound) or

zúzott sérülés (bruised injury) to describe either bruises, wounds, or even hybrid forms, thereby generating ambiguity in legal and forensic contexts. Compared to the results of a previous study, in the present one the term

zúzott seb (bruised wound) appeared in 49 injury descriptions, accounting for 23% of all blunt-force injuries involving skin disruption. In the earlier study, the term was found in 30 cases, representing 19% of all alleged laceration cases [

26]. This indicates a growing tendency to use the terminologically unclear expression

zúzott seb (bruised wound) in clinical injury descriptions, despite its ambiguous meaning from a forensic perspective.

The same applies to the distinction between abrasions and wounds caused by tangential blunt-force trauma. While in the previous study 18.4% of injuries caused by tangential blunt-force trauma were diagnosed as “abraded wounds” [

26], this number has slightly decreased to 16.3% in the present study. This differentiation is primarily found in older Hungarian forensic literature, where abrasion is described as an alteration caused by blunt force, meaning the friction or grinding of superficial epithelial layers. When the blunt force exceeds the tissue’s structural integrity, particles of tissue separate, resulting in a disruption of the skin’s continuity. Depending on whether the force strikes the body horizontally or vertically, different characteristics of a lacerated wound may develop [

41]. More recently, a new recommendation has been formulated, suggesting that abrasions leading to skin continuity disruption should be classified as

vulnus lacerum (lacerated wound). This proposal is detailed in the comprehensive terminological, dental, and forensic expert analysis by Bán et al. [

31].

From a forensic standpoint, abrasions and bruises (contusions) must be documented with particular attention to their shape, size, color, location, and any distinct patterns that may indicate the nature of the causative object (e.g., a ligature, shoe tread, or fingernail). Abrasions, caused by frictional forces, may reflect the direction of impact and are often the first to appear and the first to heal. It is essential to note whether they are linear, patterned, or brush-like. Bruises, resulting from subcutaneous bleeding, can vary in color over time and may suggest the age of the injury, but this must be interpreted cautiously. Importantly, forensic documentation should include photographs with scale, and note the depth, margins, and potential internal associations (e.g., swelling or deeper tissue damage), as these characteristics help differentiate between accidental and inflicted trauma and provide clues to the force and mechanism involved [

9,

10,

13,

42].

A discrepancy between forensic and clinical perspectives is also evident in the classification of sharp force trauma. In Hungarian surgical literature, “incised and chop wounds” (

vulnus scissum et caesum) are generally treated as a single category—defined as injuries caused by an object with a blade that is wedge-shaped in the cross-section [

35,

36,

37]. An exception to this can be found in works such as [

33,

43,

44] (

Table A1) (

Figure A1)., but usually no distinction is made in clinical management. In contrast, forensic literature clearly distinguishes between incised and chop wounds, highlighting the differences in both the mechanism and the force involved—chop wounds typically resulting from a combination of sharp and blunt force trauma [

39]. This differentiation reflects a fundamental forensic principle that injury classification should be guided by the biomechanical characteristics and causative mechanisms, rather than solely by morphological appearance. From a forensic point of view, accurately documenting sharp force injuries means paying close attention to the unique characteristics of each type of wound. Diagnostic terminology can be especially misleading when the specific morphological features that distinguish different injury types are not carefully recorded, leading to confusion and misinterpretation. Based on Collins [

45], important details for incised wounds include the sharpness of the edges, the ratio between the wound’s surface length and its depth (with the surface typically being longer), the alignment of the wound with natural skin tension lines, and whether hair is caught inside the wound. Stab wounds are different—they tend to be deeper than they are long, have flat edges with sharp angles, and do not show tissue bridging. Chop wounds, caused by a mix of sharp and blunt forces, usually have uneven edges, often come with abrasions or bruising around them, may cause fractures underneath, and sometimes carry impressions that match the weapon used. Measuring the wound’s length, width, and angle, noting patterns when multiple wounds are present, and taking clear photos with a scale are all crucial steps [

45]. In previous studies [

21,

26], 30% of sharp-force injury reports contained contradictory information, describing the same injury as both incisions and chop wounds; however, in the present study, this phenomenon was observed in only 20% of cases. However, every single case of misunderstanding related to sharp-force trauma, especially when affecting the upper body, may have serious forensic and criminal legal consequences [

17,

21].

Missing morphological characteristics combined with overly generalized diagnostic terminology can also be a major factor limiting the usefulness of clinical reports for forensic evaluation. Using broad diagnostic categories such as ICD-10—originally created for statistical and administrative reasons—to describe injuries without detailed morphological information can sometimes hide the true nature of the trauma, making forensic evaluation more difficult. These standardized categories are very helpful for clinicians who need to document cases quickly, especially when time and staff are limited, and they do provide a certain level of quality control. However, when cases are considered in legal settings, these general terms [

46] can slow down or complicate investigations, particularly if no additional evidence is available. This challenge is compounded by the fact that such categories often omit important details—such as which side or part of the body was injured, or the specific type of injury [

47]. In addition, cultural differences [

48], differing interpretations of Greek-Latin medical terms across languages [

49], and translation errors in the various national versions [

18] can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations.

In line with a previous study [

18], the present study also found a significantly more frequent use of ICD-10 categories as diagnoses in the head and neck region in Hungarian clinical reports. Many of these diagnoses contain overly generalized expressions and lack specification of the affected side and/or the exact anatomical area. As the head and neck is a clinically and forensically sensitive region with numerous coding options, clinicians appear to rely more on standardized ICD-10 codes than on individually formulated diagnoses. However, this practice may lead to misunderstandings in clinical settings, as illustrated by the Hungarian mistranslation of the ICD-10 code S07.1: “bruised injury of head” instead of the correct “crushing injury of skull” [

18] (

Table A2). Such inaccuracies may not only affect urgent clinical treatment but also compromise forensic assessment.

Accurate clinical documentation of trauma requires precise guidelines and harmonized terminology that are understandable to both clinicians and forensic experts. Waltz et al. [

23] emphasize the necessity of detailed and standardized documentation in forensic examinations to ensure quality and consistency. Unambiguous clinical documentation is also essential for the accurate assessment of disability [

50], for the forensic evaluation of injuries related to crimes [

51], and also for classifications based on treatability with simple medical intervention and life-threatening status in emergency care [

52]. It has been argued that detailed, structured reporting is essential for the accurate reconstruction of injury mechanisms and the determination of causality [

53]. Given that clinical forensic medicine operates at the interface between healthcare and the legal system, insufficient documentation can obstruct both therapeutic decisions and judicial outcomes [

11]. To address these challenges, the establishment of quality assurance frameworks has been recommended, particularly those focusing on reproducibility, clarity, and medico-legal relevance [

54]. Furthermore, interdisciplinary contributions—such as those from forensic nursing—have been shown to enhance the level of documentation, offering models that combine medical accuracy with legal interpretability [

32].

In Hungary, the authors are developing a new trauma terminology database based on recent standardized legislation, with the goal of providing harmonized, unambiguous, and sufficiently detailed injury terminology. For example, terms traditionally used only by forensic experts, such as “lacerated wound” and “chop wound,” have been clearly defined, and the term “bite injury” has been introduced in place of “bite wound” to account for the fact that bites can present in several forms. Several outdated terms previously used in Hungarian forensic medicine to describe injury characteristics, such as alávájt and letetőzött, referred broadly to subcutaneous tissue separation or undermining. These terms have been replaced with the currently accepted term lebenyes, which more precisely describes a flap-like tissue structure that remains partially attached, providing a clearer and anatomically standardized description. This harmonized terminology is intended to support both effective clinical practice and legal requirements, while remaining compatible with modern, network- and ontology-based international diagnostic classification systems.