The Transfer, Prevalence, Persistence, and Recovery of DNA from Body Areas in Forensic Science: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The role of sampling various body areas: how sampling different areas of the human body, that may have been contacted during a crime, can aid in investigations of various casework scenarios;

- An overview of current data on the prevalence of background DNA on different skin surfaces, and its potential impact on the detection of DNA transferred during physical contact;

- An examination of factors that can influence the transfer and persistence of DNA (both touch samples and various biological fluids) to different human skin surfaces;

- A summary of recovery methods used for the collection and processing of biological samples from a body for the purpose of DNA analysis;

- A discussion of the limitations in the current research that address the needs of forensic caseworkers and legal deliberators, along with suggestions for future research directions.

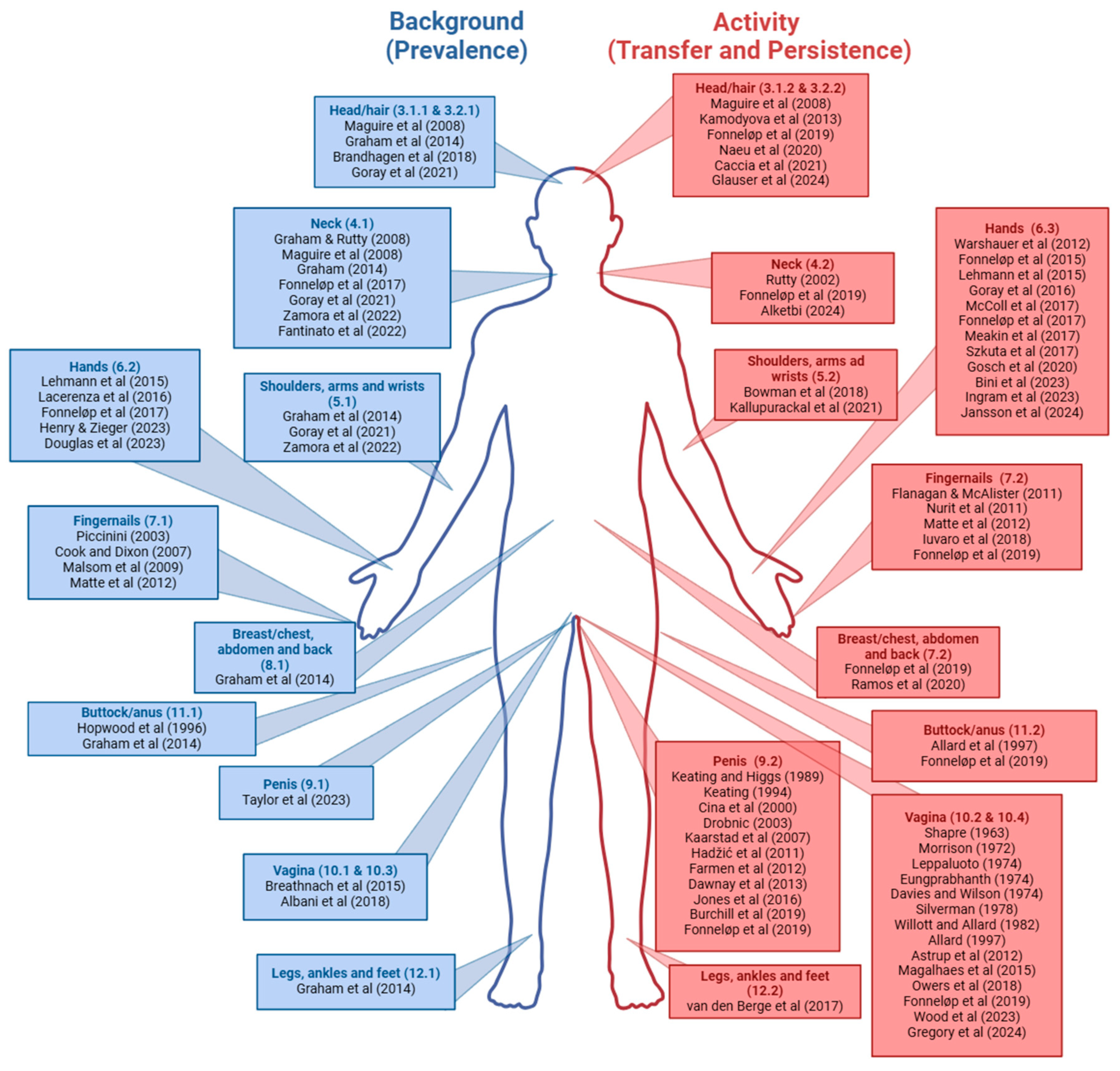

2. DNA Recovery from Body Parts

2.1. Sampling Strategies

2.1.1. Swabbing

| Technique | Body Part Commonly Sampled | Description of Sampling Technique | Relevant Papers Mentioned in Review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swabbing | External skin surfaces (i.e., skin of the face, neck, arms, legs, external surface of the penis, external area of the vagina, etc.) Internal body areas (i.e., oral cavity, vaginal cavity, penis, and anus) | Double-swabbing technique is commonly used for external samples, whereby a wet swab is applied to the sampling area, followed by a dry swab. Alternatively, a single wet swab has been shown to yield similar results. Internal samples are also typically obtained with a single swab. Swabs are generally made out of cotton or viscose. | [25,86,101,102,103] |

| Tape lifting | External skin surfaces (i.e., skin of the arms, neck, chest, legs, etc.) | Used by applying the adhesive side of tape to the target surface (including skin) to collect traces of deposited DNA. This process has been carried out on the skin of live and deceased victims. | [25,26,46,106,107,108,109] |

| Hair/pubic combings | Head and pubic hair long enough to be combed | Involves using a fine comb to brush through hair and collect biological traces onto a piece of paper or collection device placed underneath the sampled surface. | [110,111,112,113,114,115,116] |

| Fingernail scrapings/ clippings | Underneath the fingernails | Achieved by either clipping of the fingernails or using a swab or scraping device to remove any trace evidence from underneath the fingernails. | [59,75,117,118,119,120,121] |

| Mouth rinses | Oral cavity | An individual rinses a solution (generally a saline solution) in their mouth, which is then deposited into a collection device. | [105,122,123,124,125,126,127] |

| Imprints | Teeth, skin (e.g., ear, penis) | A mould is used to recover an impression (typically dental), or a glass plate or smooth surface can be used to recover an impression upon contact. | [83,128,129,130] |

2.1.2. Tape Lifting

2.1.3. Hair/Pubic Combings

2.1.4. Fingernail Scrapings/Clippings

2.1.5. Mouth Rinses

2.1.6. Imprints

2.1.7. Sampling of Areas Adjacent to Target Areas

3. Head and Hair

3.1. External Areas

3.1.1. Head and Hair: Prevalence of Background DNA

3.1.2. Head and Hair: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

3.1.3. Internal Facial Cavities: Prevalence of Background DNA

3.1.4. Internal Facial Cavities: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

4. Neck

4.1. Neck: Prevalence of Background DNA

4.2. Necks: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

5. Shoulders, Arms, and Wrists

5.1. Shoulders, Arms, and Wrists: Prevalence of Background DNA

5.2. Shoulders, Arms, and Wrists: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

6. Hands

6.1. Shedder Status and Touch DNA

6.2. Hand Samples: Prevalence of Background DNA

6.3. Hand Samples: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

7. Fingernails

7.1. Fingernails: Prevalence of Background DNA

7.2. Fingernail Samples: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

8. Breast/Chest, Abdomen, and Back

8.1. Breast/Chest, Abdomen, and Back: Prevalence of Background DNA

8.2. Breast/Chest, Abdomen, and Back: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

9. Penis

9.1. Penis: Prevalence of Background DNA

9.2. Penile Samples: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

10. Vaginal Samples

10.1. Labia and Vulva: Prevalence of Background DNA

10.2. Labia and Vulva: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

10.3. Vagina and Cervix: Prevalence of Background DNA

10.4. Vagina and Cervix: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

11. Buttocks/Anus

11.1. Buttocks/Anus: Background Levels of DNA

11.2. Buttocks/Anus: DNA Transfer and Persistence After Activity

12. Legs, Ankles, and Feet

12.1. Legs, Ankles, and Feet: Prevalence of Background DNA

12.2. Legs, Ankles, and Feet: DNA Transfer and Persistence from Activity

13. Conclusions and Future Directions

- -

- Generating more data on the background levels of DNA specific to external skin surfaces and internal body sites commonly sampled in forensic casework where suspected contact is made (i.e., skin of the face, neck, chest/breast, penis, vagina, and hands);

- -

- Establishing background levels of DNA on external skin and internal body areas less commonly sampled in forensic casework (i.e., the skin of the abdomen, back, arms, buttocks, anus, rectal cavity and perianal areas, legs, ankles, and feet);

- -

- Determining who are the likely contributors of non-self DNA on different areas of a body relevant to different situations and activities, and where possible also the biological source(s) of this/these non-self component(s);

- -

- Investigating the transfer and persistence of different biological materials (e.g., blood, semen, saliva, skin, earwax, and tears) to different common (e.g., breasts and faces) and uncommon (e.g., abdomen, back, and feet) body surfaces following different actions (e.g., kissing, biting, licking, grabbing, and pushing);

- -

- Investigating the transfer and persistence of DNA to head hair following grabbing actions reflective of actions commonly seen in assault scenarios;

- -

- Investigations of effects of various variables such as wearing and changing clothes, sharing towels, living with others, sharing a bed, washing clothes, etc., on the persistence of DNA transferred to the body;

- -

- Further investigations into various recovery methods for sampling different body areas with the aim of maximising the yield of targeted non-self-DNA, and minimising the yield of non-targeted self DNA, recovered following a transfer event.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burrill, J.; Daniel, B.; Frascione, N. A review of trace “Touch DNA” deposits: Variability factors and an exploration of cellular composition. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 39, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oorschot, R.A.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Mitchell, R.J. Forensic trace DNA: A review. Investig. Genet. 2010, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddrill, P.R. Developments in forensic DNA analysis. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.; Kokshoorn, B.; Biedermann, A. Evaluation of forensic genetics findings given activity level propositions: A review. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 36, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, K.N.; Poy, A.L.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Environmental DNA monitoring: Beware of the transition to more sensitive typing methodologies. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 45, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosch, A.; Euteneuer, J.; Preuß-Wössner, J.; Courts, C. DNA transfer to firearms in alternative realistic handling scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 48, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickenheiser, R.A. Trace DNA: A review, discussion of theory, and application of the transfer of trace quantities of DNA through skin contact. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, K.; Ballantyne, J. Single cell genomics applications in forensic science: Current state and future directions. iScience 2023, 26, 107961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, J.; Caliebe, A.; Marciano, M.; Neuschwander, P.; Seiberle, I.; Scheurer, E.; Schulz, I. DEPArray™ single-cell technology: A validation study for forensic applications. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2024, 70, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Meakin, G.E.; Kokshoorn, B.; Goray, M.; Szkuta, B. DNA Transfer in Forensic Science: Recent Progress towards Meeting Challenges. Genes 2021, 12, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Szkuta, B.; Meakin, G.E.; Kokshoorn, B.; Goray, M. DNA transfer in forensic science: A review. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 38, 140–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, P.; Hicks, T.; Butler, J.M.; Connolly, E.; Gusmão, L.; Kokshoorn, B.; Morling, N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Parson, W.; Prinz, M.; et al. DNA commission of the International society for forensic genetics: Assessing the value of forensic biological evidence—Guidelines highlighting the importance of propositions. Part II: Evaluation of biological traces considering activity level propositions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 44, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.M.; Iyer, H.; Press, R.; Taylor, M.K.; Vallone, P.M.; Willis, S. DNA Mixture Interpretation: A NIST Scientific Foundation Review (NISTIR 8351-DRAFT); National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021.

- Willis, S.M.; McKenna, L.; McDermott, S.; O’Donell, G.; Barrett, A.; Rasmusson, B.; Nordgaard, A.; Berger, C.E.H.; Sjerps, M.J.; Lucena-Molina, J.-J.; et al. ENFSI Guideline for Evaluative Reporting in Forensic Science; European Network of Forensic Science Institutes. 2015. Available online: https://enfsi.eu/docfile/enfsi-guideline-for-evaluative-reporting-in-forensic-science/ (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Atkinson, K.; Arsenault, H.; Taylor, C.; Volgin, L.; Millman, J. Transfer and persistence of DNA on items routinely encountered in forensic casework following habitual and short-duration one-time use. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 60, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonneløp, A.E.; Egeland, T.; Gill, P. Secondary and subsequent DNA transfer during criminal investigation. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 17, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, V.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Oorschot, R.A.H.v. Following the transfer of DNA: How does the presence of background DNA affect the transfer and detection of a target source of DNA? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 19, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, G.; Jamieson, A. DNA transfer: Review and implications for casework. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2013, 7, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. The complexities of DNA transfer during a social setting. Leg. Med. 2015, 17, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokshoorn, B.; Aarts, L.H.J.; Ansell, R.; Connolly, E.; Drotz, W.; Kloosterman, A.D.; McKenna, L.G.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Sharing data on DNA transfer, persistence, prevalence and recovery: Arguments for harmonization and standardization. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 37, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Ansell, R.; Boiso, L.; Connolly, E.; Kloosterman, A.D.; Kokshoorn, B.; McKenna, L.G.; Steensma, K.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Assessment of the transfer, persistence, prevalence and recovery of DNA traces from clothing: An inter-laboratory study on worn upper garments. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 42, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, J.K. Prevalence of Non-Self DNA on Three Different Sebaceous Skin Locations; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault, H.; Kuffel, A.; Daeid, N.N.; Gray, A. Trace DNA and its persistence on various surfaces: A long term study investigating the influence of surface type and environmental conditions—Part one, metals. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2024, 70, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Y.C.; Wong, H.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Waffa, Z.B.M.; Aw, Z.Q.; Fauzi, S.N.A.B.M.; Hoe, S.Y.; Lim, M.-L.; Syn, C.K.-C. Persistence of DNA in the Singapore context. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 133, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallupurackal, V.; Kummer, S.; Voegeli, P.; Kratzer, A.; Dørum, G.; Haas, C.; Hess, S. Sampling touch DNA from human skin following skin-to-skin contact in mock assault scenarios—A comparison of nine collection methods. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenna, J.; Smyth, M.; McKenna, L.; Dockery, C.; McDermott, S.D. The Recovery and Persistence of Salivary DNA on Human Skin. J. Forensic Sci. 2011, 56, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goray, M.; Pirie, E.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA transfer: DNA acquired by gloves during casework examinations. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 38, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Swabs as DNA Collection Devices for Sampling Different Biological Materials from Different Substrates. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Evaluation of tapelifting as a collection method for touch DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2014, 8, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. The influence of substrate on DNA transfer and extraction efficiency. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2013, 7, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Mitchell, R.J. Increased amplification success from forensic samples with locked nucleic acids. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2011, 5, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Mitchell, R.J. Increasing amplification success of forensic DNA samples using multiple displacement amplification. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2007, 3, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Mitchell, J.R. DNA transfer within forensic exhibit packaging: Potential for DNA loss and relocation. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Harvey, M.L.; Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA transfer by examination tools—A risk for forensic casework? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 16, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oorschot, R.A.; Treadwell, S.; Beaurepaire, J.; Holding, N.L.; Mitchell, R.J. Beware of the possibility of fingerprinting techniques transferring DNA. J. Forensic Sci. 2005, 50, 2004430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Z.E.; Mosse, K.S.; Sungaila, A.M.; van Oorschot, R.A.; Hartman, D. Detection of offender DNA following skin-to-skin contact with a victim. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 37, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuidberg, M.; Bettman, M.; Aarts, L.H.J.; Sjerps, M.; Kokshoorn, B. Targeting relevant sampling areas for human biological traces: Where to sample displaced bodies for offender DNA? Sci. Justice 2019, 59, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonneløp, A.E.; Johannessen, H.; Heen, G.; Molland, K.; Gill, P. A retrospective study on the transfer, persistence and recovery of sperm and epithelial cells in samples collected in sexual assault casework. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 43, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, M.; Seda, J. Sexual assault evidence collection. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554497/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Graham, E.A.M.; Rutty, G.N. Investigation into "Normal" Background DNA on Adult Necks: Implications for DNA Profiling of Manual Strangulation Victims. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonneløp, A.E.; Ramse, M.; Egeland, T.; Gill, P. The implications of shedder status and background DNA on direct and secondary transfer in an attack scenario. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 29, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Fowler, S.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Shedder status—An analysis of self and non-self DNA in multiple handprints deposited by the same individuals over time. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 23, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokwongnuwut, P.; Martin, B.; Kirkbride, K.P.; Linacre, A. Shedding light on shedders. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 36, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.A.M.; Watkins, W.J.; Dunstan, F.; Maguire, S.; Nuttall, D.; Swinfield, C.E.; Rutty, G.N.; Kemp, A.M. Defining background DNA levels found on the skin of children aged 0–5 years. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2014, 128, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkuta, B.; Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Transfer and persistence of DNA on the hands and the influence of activities performed. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 28, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorbo, S.; Jeuniaux, P.P.J.M.H. DNA Recovery from Tape-Lifting Kits: Methodology and Practice. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Panacek, E.; Green, W.; Kanthaswamy, S.; Hopkins, C.; Calloway, C. Recovery of salivary DNA from the skin after showering. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2015, 11, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Gunn, P.R.; Walsh, S.J.; Roux, C. Trace evidence characteristics of DNA: A preliminary investigation of the persistence of DNA at crime scenes. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2009, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Eken, E.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Secondary DNA transfer of biological substances under varying test conditions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2010, 4, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, J.E.L.; Taylor, D.; Handt, O.; Skuza, P.; Linacre, A. Direct PCR Improves the Recovery of DNA from Various Substrates. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Ellaway, B.; Bowyer, V.L.; Graham, E.A.M.; Rutty, G.N. Retrieval of DNA from the faces of children aged 0–5 years: A technical note. J. Forensic Nurs. 2008, 4, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhagen, M.D.; Loreille, O.; Irwin, J.A. Fragmented Nuclear DNA is the Predominant Genetic Material in Human Hair Shafts. Genes 2018, 9, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Shedder status: Exploring means of determination. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinato, C.; Gill, P.; Fonneløp, A.E. Non-self DNA on the neck: A 24 hours time-course study. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 57, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerenza, D.; Aneli, S.; Omedei, M.; Gino, S.; Pasino, S.; Berchialla, P.; Robino, C. A molecular exploration of human DNA/RNA co-extracted from the palmar surface of the hands and fingers. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 22, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, L.; Zieger, M. Self- and non-self-DNA on hands and sleeve cuffs. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 138, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, H.; Fraser, I.; Davidson, G.; Murphy, C.; Gorman, M.L.; Boyce, M.; Doole, S. Assessing the background levels of body fluids on hands. Sci. Justice 2023, 63, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinini, A. A 5-year study on DNA recovered from fingernail clippings in homicide cases in Milan. Int. Congr. Ser. 2003, 1239, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, O.; Dixon, L. The prevalence of mixed DNA profiles in fingernail samples taken from individuals in the general population. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2007, 1, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malsom, S.; Flanagan, N.; McAlister, C.; Dixon, L. The prevalence of mixed DNA profiles in fingernail samples taken from couples who co-habit using autosomal and Y-STRs. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2009, 3, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, M.; Williams, L.; Frappier, R.; Newman, J. Prevalence and persistence of foreign DNA beneath fingernails. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, A.J.; Mannucci, A.; Sullivan, K.M. DNA typing from human faeces. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1996, 108, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Scott, K.; Lewis, J.; Davidson, G.; Allard, J.E.; Lowrie, C.; McBride, B.M.; McKenna, L.; Teppett, G.; Rogers, C.; et al. DNA transfer through nonintimate social contact. Sci. Justice 2016, 56, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Davidson, G.; Boyce, M.; Murphy, C.; Doole, S.; Rogers, C.; Fraser, I. Background levels of body fluids and DNA on the shaft of the penis and associated underpants in the absence of sexual activity. Sci. Justice 2023, 63, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breathnach, M.; Moore, E. Background Levels of Salivary-α-amylase Plus Foreign DNA in Cases of Oral Intercourse: A Female Perspective. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albani, P.P.; Patel, J.; Fleming, R.I. Background levels of male DNA in the vaginal cavity. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 33, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutty, G.N. An investigation into the transference and survivability of human DNA following simulated manual strangulation with consideration of the problem of third party contamination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2002, 116, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alketbi, S.K. Investigating the Persistence of Touch DNA on Human Skin in Violent Crime Investigations. 2024. Available online: https://assets-eu.researchsquare.com/files/rs-4758519/v1/512e4c9b-2acb-4e5c-a5ca-c632eb08abfd.pdf?c=1721415236 (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Warshauer, D.H.; Marshall, P.; Kelley, S.; King, J.; Budowle, B. An evaluation of the transfer of saliva-derived DNA. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 126, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, G.E.; Butcher, E.V.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Morgan, R.M. Trace DNA evidence dynamics: An investigation into the deposition and persistence of directly- and indirectly-transferred DNA on regularly-used knives. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 29, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, C.; Giorgetti, A.; Fazio, G.; Amurri, S.; Pelletti, G.; Pelotti, S. Impact on touch DNA of an alcohol-based hand sanitizer used in COVID-19 prevention. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 137, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, S.; DeCorte, A.; Gentry, A.E.; Philpott, M.K.; Moldenhauer, T.; Stadler, S.; Steinberg, C.; Millman, J.; Ehrhardt, C.J. Differentiation of vaginal cells from epidermal cells using morphological and autofluorescence properties: Implications for sexual assault casework involving digital penetration. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2023, 66, 102909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.; Siti, C.; Hedell, R.; Forsberg, C.; Ansell, R.; Hedman, J. Assessing the consistency of shedder status under various experimental conditions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2024, 69, 103002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, N.; McAlister, C. The transfer and persistence of DNA under the fingernails following digital penetration of the vagina. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2011, 5, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuvaro, A.; Bini, C.; Dilloo, S.; Sarno, S.; Pelotti, S. Male DNA under female fingernails after scratching: Transfer and persistence evaluation by RT-PCR analysis and Y-STR typing. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Handt, O.; Taylor, D. Investigating the position and level of DNA transfer to undergarments during digital sexual assault. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 47, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, J.E. The collection of data from findings in cases of sexual assault and the significance of spermatozoa on vaginal, anal and oral swabs. Sci. Justice 1997, 37, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burchill, J.W. Persistence and variability of DNA: Penile washings and intimate bodily examinations in sex-related offences. Manit. Law J. 2019, 42, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.M. Information from penile swabs in sexual assault cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 1989, 43, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.M.; Higgs, D.F. The detection of amylase on swabs from sexual assault cases. J.-Forensic Sci. Soc. 1994, 34, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cina, S.J.; Collins, K.A.; Pettenati, M.J.; Fitts, M. Isolation and identification of female DNA on postcoital penile swabs. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2000, 21, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnic, K. Analysis of DNA evidence recovered from epithelial cells in penile swabs. Croat. Med. J. 2003, 44, 350–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarstad, K.; Rohde, M.; Larsen, J.; Eriksen, B.; Thomsen, J.L. The detection of female DNA from the penis in sexual assault cases. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2007, 14, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadžić, G.; Lukan, A.; Drobnič, K. Practical value of the marker MUC4 for identification of vaginal secretion in penile swabs. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2011, 3, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmen, R.K.B.P.; Haukeli, I.B.; Ruoff, P.P.; Frøyland, E.S.M. Assessing the presence of female DNA on post-coital penile swabs: Relevance to the investigation of sexual assault. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2012, 19, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawnay, N.; Sheppard, K. From crime scene to courtroom: A review of the current bioanalytical evidence workflows used in rape and sexual assault investigations in the United Kingdom. Sci. Justice 2023, 63, 206–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berge, M.; van de Merwe, L.; Sijen, T. DNA transfer and cell type inference to assist activity level reporting: Post-activity background samples as a control in dragging scenario. Forensic science international. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, e591–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharpe, N. Significance of Spermatozoa in Victims of Sexual Offenses. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1963, 186, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.I. Persistence of spermatozoa in the vagina and cervix. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 1972, 48, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppaluoto, P. Vaginal flora and sperm survival. J. Reprod. Med. 1974, 12, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Eungprabhanth, V. Finding of the spermatozoa in the vagina related to elapsed time of coitus. Z. Rechtsmed. 1974, 74, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Wilson, E. The persistence of seminal constituents in the human vagina. Forensic Sci. 1974, 3, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, E.M. Persistence of spermatozoa in the lower genital tracts of women. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1978, 240, 1875–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willott, G.M.; Allard, J.E. Spermatozoa—Their persistence after sexual intercourse. Forensic Sci. Int. 1982, 19, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrup, B.S.; Thomsen, J.L.; Lauritsen, J.; Ravn, P. Detection of spermatozoa following consensual sexual intercourse. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 221, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, T.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Silva, B.; Corte-Real, F.; Nuno Vieira, D. Biological Evidence Management for DNA Analysis in Cases of Sexual Assault. Sci. World 2015, 2015, 365674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owers, R.; McDonald, A.; Montgomerie, H.; Morse, C. A casework study comparing success rates and expectations of detecting male DNA using two different Y-STR multiplexes on vaginal swabs in sexual assault investigations where no semen has been detected. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, G.J.; Smith, J.A.S.; Gall, J.A.M. The optimal timing of forensic evidence collection following paediatric sexual assault. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2023, 95, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, B.M. Investigation and Detection Methods for Digital and Penile Penetration Without Ejaculation. Master’s Thesis, Ceder Crest College, Allentown, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Währer, J.; Kehm, S.; Allen, M.; Brauer, L.; Eidam, O.; Seiberle, I.; Kron, S.; Scheurer, E.; Schulz, I. The DNA-Buster: The evaluation of an alternative DNA recovery approach. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2023, 64, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, B.C.M.; Cheung, B.K.K. Double swab technique for collecting touched evidence. Leg. Med. 2007, 9, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, K.G.; Verheij, S.M.; Veenhoven, M.; Sijen, T. Comparison of stubbing and the double swab method for collecting offender epithelial material from a victim’s skin. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2012, 6, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, J.; Jansson, L.; Akel, Y.; Wallmark, N.; Gutierrez Liljestrand, R.; Forsberg, C.; Ansell, R. The double-swab technique versus single swabs for human DNA recovery from various surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 46, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.A.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Conlan, X.A. How the physicochemical substrate properties can influence the deposition of blood and seminal deposits. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 354, 111914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lench, N.; Stanier, P.; Williamson, R. Simple non-invasive method to obtain DNA for gene analysis. Lancet 1988, 331, 1356–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, O.; Finnebraaten, M.; Heitmann, I.K.; Ramse, M.; Bouzga, M. Trace DNA collection—Performance of minitape and three different swabs. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 2, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymus, C.M.; Baxter, F.O.; Ta, H.; Tran, T.; de Sousa, C.; Mountford, N.S.; Tay, J.W. A comparison of six adhesive tapes as tape lifts for efficient trace DNA recovery without the transfer of PCR inhibitors. Leg. Med. 2024, 67, 102330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, S.; Haas, C. Recovery of Trace DNA on Clothing: A Comparison of Mini-tape Lifting and Three Other Forensic Evidence Collection Techniques. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Bertozzi, G.; Messina, G.; Ricci, P.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V.; Cantatore, S.; Turillazzi, E.; Pomara, C. Touch DNA: Impact of handling time on touch deposit and evaluation of different recovery techniques: An experimental study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M.T.; Cook, R. Transfer of fibres to head hair, their persistence and retrieval. Forensic Sci. Int. 1996, 81, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, P.E.J. Hair as a source of forensic evidence in murder investigations. Forensic Sci. Int. 2006, 163, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, A.; Levin, N. Collection efficiency of gunshot residue (GSR) particles from hair and hands using double-side adhesive tape. J. Forensic Sci. 1993, 38, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCrehan, W.A.; Layman, M.J.; Secl, J.D. Hair combing to collect organic gunshot residues (OGSR). Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 135, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naue, J.; Sänger, T.; Lutz-Bonengel, S. Get it off, but keep it: Efficient cleaning of hair shafts with parallel DNA extraction of the surface stain. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 45, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccia, G.; Cappella, A.; Castoldi, E.; Marino, A.; Colloca, D.; Amadasi, A.; Caccianiga, M.; Lago, G.; Cattaneo, C. Blood and sperm traces on human hair. A study on preservation and detection after 3-month outdoor exposure. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, A.; Levin, N. Casework experience of GSR detection in Israel, on samples from hands, hair, and clothing using an autosearch SEM/EDX system. J. Forensic Sci. 1995, 40, 1082–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebda, L.M.; Doran, A.E.; Foran, D.R. Collecting and Analyzing DNA Evidence from Fingernails: A Comparative Study. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Hou, W.; Wei, F.; Liu, L. DNA Analysis of Fingernail Clippings: An Unusual Case Report. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2014, 35, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowlman, E.A.; Martin, N.C.; Foy, M.J.; Lochner, T.; Neocleous, T. The prevalence of mixed DNA profiles on fingernail swabs. Sci. Justice 2010, 50, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurit, B.; Anat, G.; Michal, S.; Lilach, F.; Maya, F. Evaluating the prevalence of DNA mixtures found in fingernail samples from victims and suspects in homicide cases. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2011, 5, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, P.; Bajanowski, T.; Brinkmann, B. DNA typing of debris from fingernails. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1993, 106, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigelson, H.S.; Rodriguez, C.; Robertson, A.S.; Jacobs, E.J.; Calle, E.E.; Reid, Y.A.; Thun, M.J. Determinants of DNA Yield and Quality from Buccal Cell Samples Collected with Mouthwash. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2001, 10, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Closas, M.; Egan, K.M.; Alavanja, M.; Hayes, R.B.; Rutter, J.; Buetow, K.; Brinton, L.A.; Rothman, N.; Abruzzo, J.; Newcomb, P.A.; et al. Collection of Genomic DNA from Adults in Epidemiological Studies by Buccal Cytobrush and Mouthwash. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2001, 10, 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- Hayney, M.S.; Dimanlig, P.; Lipsky, J.J.; Poland, G.A. Utility of a “Swish and Spit” Technique for the Collection of Buccal Cells for TAP Haplotype Determination. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1995, 70, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, E.M.; Morken, N.W.; Campbell, K.A.; Tkach, D.; Boyd, E.A.; Strom, D.A. Use of buccal cells collected in mouthwash as a source of DNA for clinical testing. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2001, 125, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittis, M.; Franco, M.; Cochrane, C. New oral cut-off time limits in NSW. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 44, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobal, K.; Layton, D.; Mufti, G. Non-invasive isolation of constitutional DNA for genetic analysis. Lancet 1989, 334, 1281–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishan, K.; Kanchan, T.; Garg, A.K. Dental evidence in forensic identification–An overview, methodology and present status. Open Dent. J. 2015, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamble, A.; Badiye, A.; Kapoor, N. Ear Prints in Forensic Science: An Introduction. In Textbook of Forensic Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, G. Forensic Analysis of Imprint Marks on Skin Utilizing Digital Photogrammetric Techniques. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2000, 33, 669–676. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgley, E.; Dejournett, C.; Olson, K. Utilizing differential extraction thresholds to deduce the existence of spermatozoa in forensic casework samples. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBenedetto, K. The Role of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners in Illinois. Nurs. Voice 2022, 10, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Muruganandhan, J.; Sivakumar, G. Practical aspects of DNA-based forensic studies in dentistry. J. Forensic Dent. Sci. 2011, 3, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roberts, K.A.; Johnson, D.J.; Cruz, S.; Simpson, H.; Safer, A. A Comparison of the Effectiveness of Swabbing and Flossing as a Means of Recovering Spermatozoa from the Oral Cavity. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; McArdle, R.; Goodwin, W.H.; Ballantyne, K.N. DNA transfer: The role of temperature and drying time. Leg. Med. 2014, 16, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornbury, D.; Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Indirect DNA transfer without contact from dried biological materials on various surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 51, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornbury, D.; Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Drying properties and DNA content of saliva samples taken before, during and after chewing gum. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 54, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai-Kanto, E.; Hirata, M.H.; Hirata, R.D.C.; Nunes, F.D.; Melani, R.F.H.; Oliveira, R.N. DNA extraction from human saliva deposited on skin and its use in forensic identification procedures. Braz. Oral Res. 2005, 19, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reither, J.B.; Taylor, D.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Exploring how the LR of a POI in a target sample is impacted by awareness of the profile of the background derived from an area adjacent to the target sample. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2023, 65, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reither, J.B.; Taylor, D.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Determining the number and size of background samples derived from an area adjacent to the target sample that provide the greatest support for a POI in a target sample. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2024, 68, 102977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syndercombe Court, D. Mitochondrial DNA in forensic use. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Monkman, H.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Presence of Human DNA on Household Dogs and Its Bi-Directional Transfer. Genes 2023, 14, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkman, H.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Goray, M. The role of cats in human DNA transfer. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2025, 74, 103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.; Swensson, M.; Gifvars, E.; Hedell, R.; Forsberg, C.; Ansell, R.; Hedman, J. Individual shedder status and the origin of touch DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 56, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, Y.L.A.; Gralton, J.B.P.; McLaws, M.-L.D.M.P. Face touching: A frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015, 43, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, J.; Mumin, J.; Fakhruddin, B. How Frequently Do We Touch Facial T-Zone: A Systematic Review. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Handt, O.; Goray, M. Face reality—Consider face touching behaviour on subsequent DNA analysis. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 56, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparna, R.; Shanti Iyer, R. Tears and Eyewear in Forensic Investigation—A Review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 306, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparna, R.; Iyer, R.S.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, A. Forensic DNA profiling of tears stains from commonly encountered substrates. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 328, 111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, E.A.M.; Bowyer, V.L.; Martin, V.J.; Rutty, G.N. Investigation into the usefulness of DNA profiling of earprints. Sci. Justice 2007, 47, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijerman, L.; Sholl, S.; De Conti, F.; Giacon, M.; van der Lugt, C.; Drusini, A.; Vanezis, P.; Maat, G. Exploratory study on classification and individualisation of earprints. Forensic Sci. Int. 2004, 140, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, G.L.; Gibson, C.S.; O’Callaghan, M.E.; Goldwater, P.N.; Dekker, G.A.; Haan, E.A.; MacLennan, A.H.; for the South Australian Cerebral Palsy Research Group. DNA from buccal swabs suitable for high-throughput SNP multiplex analysis. J. Biomol. Tech. JBT 2009, 20, 232. [Google Scholar]

- Nizami, S.B.; Kazmi, S.Z.H.; Abid, F.; Babar, M.M.; Noor, A.; Najam-us-Sahar, S.Z.; Khan, S.U.; Hasan, H.; Ali, M.; Gul, A. Omics Approaches in Forensic Biotechnology: Looking for Ancestry to Offence. In Omics Technologies and Bio-Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, S.A.; Alotaibi, M.N.; Shahid, S.; Alsafrani, M.; Chaudhary, A.R. Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling of Earwax DNA Obtained from Healthy Volunteers. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5741–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutsu, T.; Watanabe, K. A Proposed Procedure for Discriminating between Nasal Secretion and Saliva by RT-qPCR. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.A.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Conlan, X.A. The impact of substrate characteristics on the collection and persistence of biological materials, and their implications for forensic casework. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 356, 111951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, P.; Heimbold, C.; Klein, R.; Immel, U.; Stiller, D.; Klintschar, M. Transfer of biological stains from different surfaces. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2011, 125, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamodyová, N.; Durdiaková, J.; Celec, P.; Sedláčková, T.; Repiská, G.; Sviežená, B.; Minárik, G. Prevalence and persistence of male DNA identified in mixed saliva samples after intense kissing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2013, 7, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaschak, S.; Möller, K.; Pfeiffer, H. Potential DNA mixtures introduced through kissing. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1998, 111, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.; Uchiyama, T.; Matsuda, H.; Shimizu, K.; Takami, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Takahama, K. Mitochondrial DNA and STR typing of matter adhering to an earphone. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glauser, N.; Lim-Hitchings, Y.C.; Schaufelbühl, S.; Hess, S.; Lunstroot, K.; Massonnet, G. Fibres in the nasal cavity: A pilot study of the recovery, background, and transfer in smothering scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 354, 111890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbo, E.; Taylor, D.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Goray, M. Air DNA forensics: Novel air collection method investigations for human DNA identification. J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 70, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Taylor, D.; Bibbo, E.; Fantinato, C.; Fonneløp, A.E.; Gill, P.; Oorschot, R.A.H. Emerging use of air eDNA and its application to forensic investigations—A review. Electrophoresis 2024, 45, 916–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Taylor, D.; Bibbo, E.; Patel, D.; Fantinato, C.; Fonneløp, A.E.; Gill, P.; Oorschot, R.A.H. Up in the air: Presence and collection of DNA from air and air conditioner units. Electrophoresis 2024, 45, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowik, V.; Lovatt, H.; Cheyne, N. Non-fatal strangulation: A highly lethal form of gendered violence. Available online: https://noviolence.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Integrated-Lit-Review-NFS-FV-23.08.22.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Stellpflug, S.J.; Taylor, A.D.; Dooley, A.E.; Carlson, A.M.; LeFevere, R.C. Analysis of a Consecutive Retrospective Cohort of Strangulation Victims Evaluated by a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Consult Service. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2022, 48, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, F.; Collins, S.; Dehn, A.; Doig, S. Vascular injury is an infrequent finding following non-fatal strangulation in two Australian trauma centres. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2022, 34, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, A.M.; Breathnach, M.; Doak, S.; Thornton, F.; Noone, C.; McKenna, L.G. Wearer and non-wearer DNA on the collars and cuffs of upper garments of worn clothing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 34, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.J.; Lee, S.B.; Barloewen, B. Comparing Wearer DNA Sample Collection Methods for the Recovery of Single Source Profiles. Themis 2013, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, G.E.; Jacques, G.S.; Morgan, R.M. Comparison of DNA recovery methods and locations from regularly-worn hooded jumpers before and after use by a second wearer. Sci. Justice 2024, 64, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McColl, D.L.; Harvey, M.L.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. DNA transfer by different parts of a hand. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen, J.; Peter, G.; Arne, R.; Ane Elida, F. Determination of shedder status: A comparison of two methods involving cell counting in fingerprints and the DNA analysis of handheld tubes. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 53, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.; Murray, C.; Whitaker, J.; Tully, G.; Gill, P. The propensity of individuals to deposit DNA and secondary transfer of low level DNA from individuals to inert surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. 2002, 129, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzo, P.; Mazzobel, E.; Marcante, B.; Delicati, A.; Caenazzo, L. Touch DNA Sampling Methods: Efficacy Evaluation and Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokwongnuwut, P.; Kirkbride, K.P.; Linacre, A. Detection of latent DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 37, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Jones, M.K. DNA fingerprints from fingerprints. Nature 1997, 387, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.; Petricevic, S. The tendency of individuals to transfer DNA to handled items. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007, 168, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Linacre, A.; Goray, M. How to best assess shedder status: A comparison of popular shedder tests. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2024, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.; Volgin, L.; Kokshoorn, B.; Champod, C. The importance of considering common sources of unknown DNA when evaluating findings given activity level propositions. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 53, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, V.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; Ballantyne, K.N.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Following the transfer of DNA: How far can it go? Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2013, 4, e53–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oorschot, R.A.H.; McColl, D.L.; Alderton, J.E.; Harvey, M.L.; Mitchell, R.J.; Szkuta, B. Activities between activities of focus—Relevant when assessing DNA transfer probabilities. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 5, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, C.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Hand activities during robberies—Relevance to consideration of DNA transfer and detection. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cale, C.M.; Earll, M.E.; Latham, K.E.; Bush, G.L. Could Secondary DNA Transfer Falsely Place Someone at the Scene of a Crime? J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goray, M.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Szkuta, B.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. Cale CM, Earll ME, Latham KE, Bush GL. Could Secondary DNA Transfer Falsely Place Someone at the Scene of a Crime? J Forensic Sci 2016;61(1):196–203. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 1396–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokshoorn, B.; Aarts, B.; Ansell, R.; McKenna, L.; Connolly, E.; Drotz, W.; Kloosterman, A.D. Cale CM, Earll ME, Latham KE, Bush GL. Could Secondary DNA Transfer Falsely Place Someone at the Scene of a Crime? J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 1401–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Taylor, D.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Best, G.; Goray, M. Classification of epidermal, buccal, penile and vaginal epithelial cells using morphological characteristics measured by imaging flow cytometry. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 365, 112274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, H.; Gill, P.; Shanthan, G.; Fonneløp, A.E. Transfer, persistence and recovery of DNA and mRNA vaginal mucosa markers after intimate and social contact with Bayesian network analysis for activity level reporting. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2022, 60, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breathnach, M.; Williams, L.; McKenna, L.; Moore, E. Probability of detection of DNA deposited by habitual wearer and/or the second individual who touched the garment. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 20, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feia, A.; Novroski, N. The Evaluation of Possible False Positives with Detergents when Performing Amylase Serological Testing on Clothing. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, S183–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wornes, D.J.; Speers, S.J.; Murakami, J.A. The evaluation and validation of Phadebas® paper as a presumptive screening tool for saliva on forensic exhibits. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 288, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, D.G.; Price, J. The sensitivity and specificity of the RSID™-saliva kit for the detection of human salivary amylase in the Forensic Science Laboratory, Dublin, Ireland. Forensic Sci. Int. 2010, 194, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, S.M.; Higgs, D.F. Oral sex—Further information from sexual assault cases. J.-Forensic Sci. Soc. 1992, 32, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berge, M.; Sijen, T. Development of a combined differential DNA/RNA co-extraction protocol and its application in forensic casework. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2022, 5, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.; Hanson, E.; Anjos, M.J.; Banemann, R.; Berti, A.; Borges, E.; Carracedo, A.; Carvalho, M.; Courts, C.; De Cock, G.; et al. RNA/DNA co-analysis from human saliva and semen stains—Results of a third collaborative EDNAP exercise. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2013, 7, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.; Klesser, B.; Maake, C.; Bär, W.; Kratzer, A. mRNA profiling for body fluid identification by reverse transcription endpoint PCR and realtime PCR. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2009, 3, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijen, T. Molecular approaches for forensic cell type identification: On mRNA, miRNA, DNA methylation and microbial markers. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 18, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allery, J.-P.; Telmon, N.; Mieusset, R.; Blanc, A.; Rougé, D. Cytological detection of spermatozoa: Comparison of three staining methods. J. Forensic Sci. 2001, 46, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Kenna, J.; Flanagan, L.; Lee Gorman, M.; Boland, C.; Ryan, J. A Study of the Background Levels of Male DNA on Underpants Worn by Females. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzo, P.; Ponzano, E.; Spigarolo, G.; Nespeca, P.; Caenazzo, L. Collecting sexual assault history and forensic evidence from adult women in the emergency department: A retrospective study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M. The forensic aspects of sexual violence. Best Pract. Research. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 27, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joki-Erkkilä, M.; Tuomisto, S.; Seppänen, M.; Huhtala, H.; Ahola, A.; Rainio, J.; Karhunen, P.J. Clinical forensic sample collection techniques following consensual intercourse in volunteers—Cervical canal brush compared to conventional swabs. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2014, 27, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeve, A.J.; Bilo, R.A.C.; Emirdag, E.; Sharify, M.; Jansen, F.W.; Dankelman, J. In vitro validation of vaginal sampling in rape victims: The problem of Locard’s principle. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2013, 9, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culhane, J.F.; Nyirjesy, P.; McCollum, K.; Casabellata, G.; Di Santolo, M.; Cauci, S. Evaluation of semen detection in vaginal secretions: Comparison of four methods. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008, 60, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.R.; Hoffman, S.A. Prostatic acid phosphatase and sperm in the post-coital vagina. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1982, 11, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, J.; Richards, E. Persistence of spermatozoa: Lessons learned from going to the sources. Sci. Justice 2018, 58, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, B. Persistence of vaginal spermatozoa as assessed by routine cervicovaginal (PAP) smears. J. Forensic Sci. 1987, 32, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, J.E.; Overstreet, J.W.; Hanson, F.W. Assessment of human sperm function after recovery from the female reproductive tract. Biol. Reprod. 1984, 31, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.C.; Pirie, A.A.; Ford, L.V.; Callaghan, C.L.; McTurk, K.; Lucy, D.; Scrimger, D.G. The use of phosphate buffered saline for the recovery of cells and spermatozoa from swabs. Sci. Justice 2007, 46, 179–184, Erratum in Sci. Justice 2007, 47, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, A.N.; Burgess, A.W. Sexual dysfunction during rape. N. Engl. J. Med. 1977, 297, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.; Jones, E.; Lewis, J.; O’Rourke, P. Y-STR analysis of digital and/or penile penetration cases with no detected spermatozoa. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 15, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziegelewski, M.; Simich, J.P.; Rittenhouse-Olson, K. Use of a Y chromosome probe as an aid in the forensic proof of sexual assault. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdon, T.J.; Mitchell, R.J.; Chen, W.; Xiao, K.; van Oorschot, R.A.H. FACS separation of non-compromised forensically relevant biological mixtures. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 14, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, S.; Philpott, M.K.; Ehrhardt, C.J. Novel cellular signatures for determining time since deposition for trace DNA evidence. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2022, 8, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, K.M. Flow cytometry: An overview. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2018, 120, 5.1.1–5.1.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoell, W.M.J.; Klintschar, M.; Mirhashemi, R.; Pertl, B. Separation of sperm and vaginal cells with flow cytometry for DNA typing after sexual assault. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 94, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.L.; Presler-Jur, P.; Mills, H.; Miles, S. Evidence collection and analysis for touch deoxyribonucleic acid in groping and sexual assault cases. J. Forensic Nurs. 2021, 17, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Laca, A.; Soriano, L.; Gleeson, D.; Godoy, J.A. A simple and effective method for obtaining mammal DNA from faeces. Wildl. Biol. 2015, 21, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.E.; Proctor-Bonbright, J.W.; Yu, J.Y. Rectal swab DNA collection protocol for PCR genotyping in rats. BioTechniques 2024, 76, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, N.; van Oorschot, R.A. Extraction of human nuclear DNA from feces samples using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 15502. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berge, M.; Ozcanhan, G.; Zijlstra, S.; Lindenbergh, A.; Sijen, T. Prevalence of human cell material: DNA and RNA profiling of public and private objects and after activity scenarios. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 21, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenker, A.; Grimble, K.; Azim, A.; Owen, R.; Hartman, D. Toenails as an alternative source material for the extraction of DNA from decomposed human remains. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 258, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogervorst, J.G.; Godschalk, R.W.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Verhage, B.A.; Jonkers, L.; Goessens, J.; Simons, C.C.; Vermeesch, J.R.; van Schooten, F.J. DNA from nails for genetic analyses in large-scale epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 2703–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Publication Year | Sample Size | Sample Type | Maximum Time of Persistence | Optimum Recovery Time Post-Intercourse | Recovery Rate of Spermatozoa at Max. Time of Persistence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharpe [88] | 1963 | Not indicated | Vaginal swabs and cervical smears | Motile sperm—6 h Non-motile sperm—up to 4 days | 6 to 12 h | Not indicated |

| Morrison [89] | 1972 | 178 | Vaginal swabs and cervical scrapings | 9 days in the vagina, 12 days in the cervix | 48 h | 58.4% |

| Leppaluoto [90] | 1974 | 300 | Cervical scrapings | 7 days | <2 days | 46% |

| Eungprabhanth [91] | 1974 | 200 | Vaginal swabs | 7 days | 48 h (80% recovery) | 33% up to 5 days |

| Davies and Wilson [92] | 1974 | Not indicated | Vaginal swabs | 6 days | <3 days | 34% (between 90 and 156 h) |

| Randall [206] | 1987 | 349 | Cervical scraping | 7 days | <1 day (maximum 25% recovery rate) | 14% (reordered at 5 days) |

| Silverman [93] | 1978 | 675 | Cervical smear | 10 days | <1 day (approximately 65%) | 25% |

| Ricci and Hoffman [204] | 1982 | 90 | Vaginal swabs | 7 days | <1 day | Not indicated |

| Gould et al. [207] | 1984 | 60 | Vaginal swabs | 5 days (motile sperm) | 12 h | Not indicated |

| Allery et al. [197] | 2001 | 174 | Vaginal swabs | 3 days | <72 h | 35.1% |

| Culhane et al. [203] | 2008 | 302 | Vaginal secretions | Only investigates up to 2 days since intercourse | Not indicated | 15.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Woollacott, C.; Goray, M.; van Oorschot, R.A.H.; Taylor, D. The Transfer, Prevalence, Persistence, and Recovery of DNA from Body Areas in Forensic Science: A Review. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5010009

Woollacott C, Goray M, van Oorschot RAH, Taylor D. The Transfer, Prevalence, Persistence, and Recovery of DNA from Body Areas in Forensic Science: A Review. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoollacott, Cara, Mariya Goray, Roland A. H. van Oorschot, and Duncan Taylor. 2025. "The Transfer, Prevalence, Persistence, and Recovery of DNA from Body Areas in Forensic Science: A Review" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5010009

APA StyleWoollacott, C., Goray, M., van Oorschot, R. A. H., & Taylor, D. (2025). The Transfer, Prevalence, Persistence, and Recovery of DNA from Body Areas in Forensic Science: A Review. Forensic Sciences, 5(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5010009