Factors Considered for the Assessment of Risk in Administrative Review Boards of Canada: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Notion of Risk and Violence in Forensic Psychiatry and Mental Health

1.2. Not Criminally Responsible Due to Mental Disorder: Canada

1.3. Administrative Courts and Risk Assessments

1.4. Objectives and Hypotheses

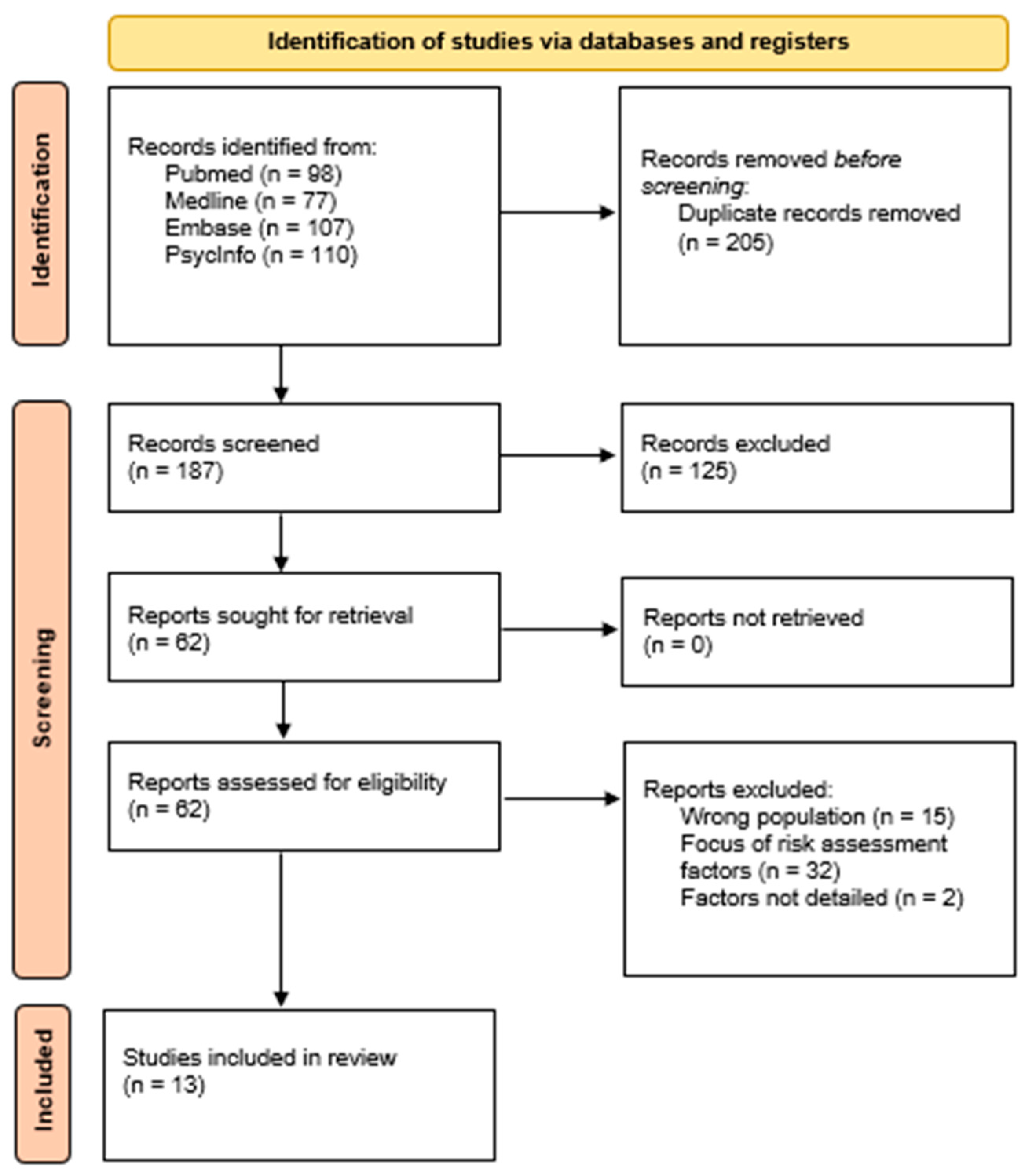

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Studies Identified

3.2. Historical Factors

3.3. Clinical Factors

3.4. Behavioral Factors

3.5. Legal Factors

3.6. Control and Miscellaneous Factors

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiesner, M.; Capaldi, D.M.; Kerr, D.C.R.; Wu, W. Bidirectional Associations of Mental Health with Self-Reported Criminal Offending over Time for At-Risk Early Adult Men in the USA. J. Dev. Life Course Criminol. 2023, 9, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, D.; Lichtenstein, P.; Fazel, S. Violence and mental disorders: A structured review of associations by individual diagnoses, risk factors, and risk assessment. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbogen, E.B.; Johnson, S.C. The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Grann, M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahji, A. Navigating the Complex Intersection of Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, R.D. Association between physical activity and mental disorders among adults in the United States. Prev. Med. 2003, 36, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, C.; Ten Have, M.; de Graaf, R.; van Schaik, D.J.F.; Kikkert, M.J.; Dekker, J.J.M.; Beekman, A.T.F. Mental disorders and the risk of adult violent and psychological victimisation: A prospective, population-based study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevillion, K.; Oram, S.; Feder, G.; Howard, L.M. Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Morris, S.B.; Michaels, P.J.; Rafacz, J.D.; Rüsch, N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrey, E.F. Stigma and violence: Isn’t it time to connect the dots? Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, H. Violence and mental illness: An overview. World Psychiatry 2003, 2, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swanson, J.W. Preventing the unpredicted: Managing violence risk in mental health care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, R.E.; Essock, S.M.; Shaner, A.; Carey, K.B.; Minkoff, K.; Kola, L.; Lynde, D.; Osher, F.C.; Clark, R.E.; Rickards, L. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coid, J.W.; Ullrich, S.; Kallis, C.; Freestone, M.; Gonzalez, R.; Bui, L.; Igoumenou, A.; Constantinou, A.; Fenton, N.; Marsh, W.; et al. Improving Risk Management for Violence in Mental Health Services: A Multimethods Approach; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, E.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Zwi, A.B. The world report on violence and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E.G.; Ijadi-Maghsoodi, R.; Shadravan, S.; Moore, E.; Mensah, M.O.; Docherty, M.; Nunez, M.G.A.; Barcelo, N.; Goodsmith, N.; Halpin, L.E.; et al. Community Interventions to Promote Mental Health and Social Equity. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charette, Y.; Crocker, A.G.; Seto, M.C.; Salem, L.; Nicholls, T.L.; Caulet, M. The national trajectory project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 4: Criminal recidivism. Can. J. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, Legislative Services. “Consolidated Federal Laws of Canada, Criminal Code”. Criminal Code. Available online: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Math, S.B.; Kumar, C.N.; Moirangthem, S. Insanity Defense: Past, Present, and Future. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2015, 37, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, P.; Langlois-Klassen, C. The role and powers of forensic psychiatric Review Boards in Canada: Recent developments. Health Law J. 2006, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, A.G.; Charette, Y.; Seto, M.C.; Nicholls, T.L.; Côté, G.; Caulet, M. The national trajectory project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 3: Trajectories and outcomes through the forensic system. Can. J. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, R.L.; Gray, J.E. Canada’s mental health legislation. Int. Psychiatry 2014, 11, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, A.G.; Nicholls, T.L.; Charette, Y.; Seto, M.C. Dynamic and static factors associated with discharge dispositions: The national trajectory project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder (NCRMD) in Canada. Behav. Sci. Law 2014, 32, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, G.; Crocker, A.G.; Nicholls, T.L.; Seto, M.C. Risk assessment instruments in clinical practice. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Barlow, S.; Reynolds, L.; Drey, N.; Begum, F.; Tuudah, E.; Simpson, A. Mental health professionals’ perceived barriers and enablers to shared decision-making in risk assessment and risk management: A qualitative systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir-Cochrane, E.; Gerace, A.; Mosel, K.; O’Kane, D.; Barkway, P.; Curren, D.; Oster, C. Managing risk: Clinical decision-making in mental health services. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 32, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaimowitz, G.A.; Mamak, M.; Moulden, H.M.; Furimsky, I.; Olagunju, A.T. Implementation of risk assessment tools in psychiatric services. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2020, 40, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, A.G.; Braithwaite, E.; Côté, G.; Nicholls, T.L.; Seto, M.C. To detain or to release? Correlates of dispositions for individuals declared not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, N.Z.; Simpson, A.I.; Ham, E. The increasing influence of risk assessment on forensic patient review board decisions. Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.M.; Nicholls, T.L.; Charette, Y.; Seto, M.C.; Crocker, A.G. Factors Associated with Review Board Dispositions following Re-hospitalization among Discharged Persons found Not Criminally Responsible. Behav. Sci. Law 2016, 34, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, N.Z.; Ham, E.; Kim, S. The influence of changes in clinical factors on high-security forensic custody dispositions. Behav. Sci. Law 2022, 40, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Olver, M.E.; Haag, A.M.; Wormith, J.S. Static and dynamic predictors of forensic mental health decision-making. Psychol. Serv. 2023, 20, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Martin, E. Factors influencing treatment team recommendations to review tribunals for forensic psychiatric patients. Behav. Sci. Law 2016, 34, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.M.; Crocker, A.G.; Nicholls, T.L.; Charette, Y.; Seto, M.C. The use of risk and need factors in forensic mental health decision-making and the role of gender and index offense severity. Behav. Sci. Law 2015, 33, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denomme, W.J.; Curno, J.; Forth, A. Psychopathic traits, risk and protective factors, and attractiveness in forensic psychiatric patients: Their role in review board dispositions. J. Forensic Psychol. Res. Pract. 2020, 20, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Martin, K.; Marshall, L. Do review tribunals consider protective factors in their decisions about patients found not criminally responsible? J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2019, 30, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.C.; Leclair, M.C.; Wilson, C.M.; Nicholls, T.L.; Crocker, A.G. Comparing persons found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder for sexual offences versus nonsexual violent offences. J. Sex. Aggress. 2018, 24, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.B.; Holoshitz, Y.; Nossel, I. Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: Review and update World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 13–20. Correction in World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, M.; Potvin, S.; Dellazizzo, L.; Luigi, M.; Giguère, C.E.; Dumais, A. Trajectories of Dynamic Risk Factors as Predictors of Violence and Criminality in Patients Discharged From Mental Health Services: A Longitudinal Study Using Growth Mixture Modeling. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dorn, R.; Volavka, J.; Johnson, N. Mental disorder and violence: Is there a relationship beyond substance use? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S. At Risk of Rights: Rehabilitation, Sentence Management and the Structural Violence of Prison. Crit. Crim. 2020, 28, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse van Rensburg, E.; van der Wath, A. Risk Assessment in Mental Health Practice: An Integrative Review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.; Shehtman, M. Clinical risk factors of acute severe or fatal violence among forensic mental health patients. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 275, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, S.; Lichtenstein, P.; Grann, M.; Goodwin, G.M.; Långström, N. Bipolar disorder and violent crime: New evidence from population-based longitudinal studies and systematic review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, E.; Buchanan, A.; Fahy, T. Violence and schizophrenia: Examining the evidence. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, A.; Whiting, D.; Fazel, S. Violence prevention in psychiatry: An umbrella review of interventions in general and forensic psychiatry. J. Forens. Psychiatry Psychol. 2017, 28, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Population | Risk Factors Assessed | Type of Risk Factors | Topic of the Study | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Côté, G., et al. (2012) [24] | Patients found NCRMD, aged 18–65, recruited from Quebec’s forensic psychiatric hospital and 2 hospitals in the Montreal metropolitan area, had a hearing between Oct 2004 and Aug 2006. N = 96 men | HCR-20 items | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors | Representation of HCR-20 items in mental health review board hearings and level of agreement between the scale items identified by the research team and the items noted by the clinicians in their reports and discussed during the hearing. | Very few of the HCR-20 items identified by research team were present in the hearing process, either in clinical reports, discussions during the hearing, or disposition justifications. There was agreement for only two historical items, H1 (previous violence) and H6 (major mental illness), with moderate agreement for substance abuse problems and clinical indicators, but no higher than moderate agreement for any risk management items. The low agreement for antisocial personality traits and psychopathy, despite their documented importance in forensic mental health literature, was particularly striking and surprising. |

| Crocker, A. G., et al. (2011) [28] | Patients found NCRMD, aged 18–65, recruited from Quebec’s forensic psychiatric hospital and 2 Montreal metropolitan area hospitals, had a hearing between Oct 2004 and Aug 2006. N = 96 men | Sociodemographic factors, previous disposition, index offense, criminal history, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, serious mental illness, antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, psychopathy with PCL-R score, risk assessment with HCR-20, VRAG | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Legal factors | Mental health review board dispositions (detention, discharge) | Review boards rely on dynamic (clinical) factors more than historical factors to make the decision to detain or to release people found NCRMD. Previous disposition, HCR-20 clinical subscale and the severity of index offense were significantly associated with detention. Neither the VRAG nor total PCL-R scores distinguished review board dispositions. |

| Crocker, A. G., et al. (2014) [23] | Men and women found NCRMD in British Columbia, Québec and Ontario between May 2000 and April 2005, followed until Dec 2008. N = 1794 | Static predictors: province (Québec, Ontario, British Columbia), age at the index verdict, gender, severity of the index offense, presence of psychiatric history, dynamic predictors: behaviors since previous hearing (violent act, suicidal attempt or thoughts, non-compliance with mental health review board conditions, substance use, non-compliance with medication), diagnosis (psychotic spectrum, mood spectrum, other axis 1 diagnosis, substance use spectrum, personality spectrum, diagnosis not specified), use of structured risk assessment tool, number of HCR-20 items mentioned at hearing as present (historical, clinical, and risk items), sequence of hearing in time | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Legal Factors | Mental health review boards dispositions (detention, conditional discharge, absolute discharge) | Review boards considered a combination of evidence-based static and dynamic risk factors, as depicted by the items of the HCR-20, but presentation of a complete structured risk assessment was rare (17%). Historical (static) factors were more influential on a conditional discharge decision and had less importance over time, compared to clinical (dynamic) factors, which had more influence on an absolute discharge decision and took more importance over time. The individuals with more severe index offense were less likely to receive a release decision. The presence of a violent act since the previous hearing decreased the likelihood of being released on conditional or absolute discharge. Psychiatric history before the index offense reduced the likelihood of being released from detention. |

| Hilton, N. Z., et al. (2016) [29] | Patients found NCRMD and detained in a maximum security psychiatric hospital in Ontario, which were admitted between 2009–2011 and followed until 2012. N = 63 men | Psychiatrists’ testimony, multidisciplinary team recommendations, VRAG score (coded by research team), VRAG, HCR-20 and PCL-R cited, participation in therapeutic activities (skills therapy, group therapy, individual therapy, counseling), refusal to participate in therapy, insight into mental illness | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Control and Miscellaneous Factors | Mental health review board dispositions (detention vs. transfer or discharge (binary)), psychiatrists’ testimony | Dispositions were most strongly associated with psychiatrists’ testimony and VRAG scores, indicating that detained patients had a higher risk of violent recidivism than transferred patients. Dispositions also correlated with HCR-20 scores, where detained patients had higher scores. Participation in group therapy and other therapeutic activities influenced psychiatrists’ recommendations for transfer and detention, independent of the patients’ length of stay. |

| Wilson, C. M., et al. (2016) [30] | Men and women from the three largest Canadian provinces (BC, QC, ON) found NCRMD between May 2000 and April 2005, who received at least one conditional discharge decision from the RB before December 2008. N = 1367 | Static factors: province (Québec, Ontario, British Columbia), age at the index verdict, sex, severity of the index offense, presence of psychiatric history, diagnosis (psychotic spectrum, substance abuse, personality disorder, diagnosis not specified), Dynamic factors: number of past hearings, rehospitalization, presence of systematic evaluation, behavior since the last hearing (violence, substance use, suicidal attempt or thoughts, non-compliance with mental health review board conditions, non-compliance with medication), number of HCR-20 items | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Legal Factors | Revocation of conditional discharge, rehospitalization | The greater presence of clinical items resulted in a higher likelihood of hospital detention at the next hearing, especially for the re-hospitalized group. The re-hospitalized group was younger, more likely diagnosed with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, engaged in concerning behaviors, and had more H, C, and R items reported. Ontario individuals, those with a psychiatric history, or those who committed a violent act during conditional discharge were more likely to be detained, with the number of clinical items being a strong factor in the detention decision. The number of historical and risk items from the HCR-20 did not influence the decision process of the review board. |

| Hilton, N. Z., et al. (2022) [31] | Men found NCRMD and admitted to a high-security forensic hospital in Ontario from 2009 to 2012 (and decisions made up to 2014). N = 89 | VRAG score, severity of the index offense (Cormier Lang Criminal History Score), In-hospital physical assaults, score on the Problem Identification Checklist (i.e., PIC, measures in-hospital clinical factors: psychotic behaviors subscale, social withdrawal subscale, inappropriate behaviors scale, mood problems scale), medication noncompliance | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors | Mental health review board disposition at hearings held in the first, second, and third years of each man’s hospitalization (detained or transferred/discharged). | Almost half of initial RB dispositions were for men to remain in high-security custody, mainly due to in-hospital clinical factors such as assaults and PIC scores, rather than index severity, VRAG scores, or medication compliance. Over time, the odds of remaining in high-security custody increased significantly, with clinical presentation and PIC scores being more crucial than the number of in-hospital assaults. Clinical recovery indicators were more influential than violence risk in determining dispositions, emphasizing mental health improvement. |

| Cheng, J., et al. (2023) [32] | Alberta NCRMD cohort that entered the review board system between 2005 and 2010 and their respective review board hearings until 2015. N = 109 | Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI), HCR-20V3, VRAG-R, Static and dynamic factors not captured by the study instruments: Static factors included sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender, ancestry) and index offense severity, dynamic factors included Institutional conduct divided into: (a) violence, (b) suicide attempts or ideation, (c) breach of RB conditions, (d) substance use, and (e) treatment noncompliance, diagnoses, number of hearings since the NCR verdict, previous disposition status, use of other risk instrument type (PCL-R, SAVRY, Static-99, SARA, SVR-20, SAM) | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Legal Factors | Mental health review board dispositions (detention, conditional discharge, absolute discharge) | Risk instruments were routinely included in clinical reports, with usage increasing from 54% at the first hearing to 92% at the third, predominantly by psychiatrists using HCR-20, followed by Psychopathy Checklist—revised, and VRAG-R. Despite this, the LS/CMI items were often unscorable due to incomplete profiles, indicating that central criminogenic risk/need factors were not fully captured in reports. Dispositions were significantly predicted by independently coded LS/CMI total scores, with pro-criminal attitudes, antisocial patterns, and companions consistently emerging as significant predictors, while previous disposition status was the strongest predictor in later hearings. |

| Martin, K. and E. Martin (2016) [33] | Inpatients from a public provincial psychiatric hospital who were under the jurisdiction of the review board between January 1, 2009, and September 1, 2013. N = 291 | Demographic variables (age at time of recommendation to the review board, ethnicity, education, employment at time of index offence (part time, full time, or unemployed), marital status at time of index offence (single/never married, married/common-law, separated/divorced, or widowed), and social support (yes or no), psychopathy (PCL-R score), violence risk (using the HCR-20 version 23), index offence (murder, sexual violence, serious physical violence, less serious physical violence, verbal violence (e.g., threats), or non-violent behavior), and number of past convictions for violent behavior, axis II disorder (yes or no), presence of active psychiatric symptoms (active or not active), age at first hospitalization, medication (oral, depot, or no medication), level of insight into illness (none, limited, moderate, or full), level of participation in recreational, vocational, therapeutic programming in the past year (number of activities engaged in), time in hospital since NCR finding, and number of notable negative events in the last year (e.g., elopements, drug use, etc.) | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Control and Miscellaneous Factors | Treatment team recommendations for review board (move to a lesser secure environment or stay at their current level of security) for 2 different comparison groups: medium secure unit and minimum secure unit. | Psychotic symptoms and overall violence risk level (measured by HCR-20) were the main factors influencing treatment teams’ recommendations for transferring patients from medium to minimum secure units. Factors such as violent behavior, insight, and participation were correlated but not predictive of these recommendations; patients transferred to minimum security showed more engagement in treatment and fewer violent incidents. Treatment teams on minimum security units focused less on empirically validated risk factors and more on factors such as fewer negative incidents when considering the addition of a community living provision to the disposition, possibly using it as motivational tools rather than focusing solely on risk assessment. |

| Wilson, C. M., et al. (2015) [34] | Individuals found NCRMD in British Columbia, Ontario, and Québec between May 2000 and April 2005, who had at least one hearing with a review board. N = 1794 The sample represents the full population of NCRMD adults for BC and ON within their respective time frames and a regionally stratified random sample for QC. Files were reviewed from 2000 to 2008. | Index offense severity, gender. Control variables: province, age at index offense, time since index verdict, index offense severity | Historical Factors, Legal Factors | Mention of risk factors in expert reports and in review board decisions (items of the HCR-20 or the VRAG), regardless of whether the item is present or absent for the individual. | A complete risk assessment measure was infrequently completed, with the HCR-20 and VRAG used in only 8% and 9% of hearings, respectively. The mean number of HCR-20 items in expert reports was 8.59, and VRAG items were 5.10, with significant agreement between expert reports and review board decisions focusing on mental health, treatment, and criminal history. Factors such as relationship instability and stress were more likely to be mentioned for women, while substance use and psychopathy were more likely for men, indicating some gender differences in risk factor consideration. |

| Crocker, A.G., et al. (2015) [21] | Men and women found NCRMD in British Columbia, Quebec, and Ontario between May 2000 and April 2005, followed until December 2008. N = 1800 | Fitness evaluation, hearing participants, initial disposition, reasons for hearing, duration under mental health review board, province, number of past criminal convictions, diagnosis at NCRMD verdict (psychosis spectrum disorder, mood disorder, substance use disorder, personality disorder), index NCRMD offense | Historical Factors, Clinical factors, Legal Factors | Mental health review board decisions, associated conditions, as well the agreement between clinical recommendations and the review board decisions. | Most reports (86.9%) included a recommended disposition, with a high agreement (86.9%) between clinician recommendations and review board decisions, though this varied across provinces. The odds of being conditionally or absolutely discharged varied significantly across provinces, with Quebec having higher discharge rates compared to Ontario and British Columbia, even after controlling for factors such as past offenses and diagnosis at verdict. A higher number of past offenses and a psychotic spectrum diagnosis decreased the likelihood of discharge, while the severity of the index offense significantly affected the duration of detention and RB supervision across all provinces. |

| Denomme, W. J., et al. (2020) [35] | Male NCRMD patients from a mental health facility in Canada, who had a hearing held between 2007 and 2014. N = 62 | Risk factors, protective factors and psychopathic traits (items from the HCR-20, SAPROF, and PCL-R scales), physical attractiveness, severity of index offense, criminal history (Cormier-Lang criminal history scale), diagnosis and demographics | Historical Factors, Clinical Factors, Behavioral Factors, Control and Miscellaneous Factors | Mental health review board disposition (discharge or detainment) | The sample had a mean number of 11.50 HCR-20 item mentions, 4.36 PCL-R item mentions, and 8.86 SAPROF item mentions in clinician reports. Attractiveness and PCL-R item mentions significantly influenced dispositional outcomes, with higher attractiveness increasing the odds of discharge and more PCL-R mentions increasing the odds of detainment. Analyses showed a significant emphasis on psychopathic traits and risk factors in decisions to detain NCRMD patients, indicating a potential overemphasis on risk, while underemphasizing protective factors. Detained individuals had a higher number of clinically relevant items mentioned in their expert reports (i.e., lack of insight, negative attitudes, active symptoms, impulsivity, unresponsiveness to treatment). |

| Collins, C., et al. (2019) [36] | Patients randomly selected from a public psychiatric hospital in Ontario, who had a hearing held between July 2016 and June 2017. N = 116 | Items from the SAPROF (protective factors) | Historical Factors, Clinical factors, Legal Factors | Disposition outcome (no change, decreased security, increased security). | On average, less than half of the SAPROF items are mentioned in hospital reports and only about a third in reasons documents, with external items being mentioned most frequently. Dispositions specifying a transfer to a higher security setting had significantly fewer references to SAPROF items compared to those specifying no change or less security. The discussion of protective factors is limited and mainly includes external factors, suggesting an overreliance on traditional risk assessment and potentially leading to unjust detentions and misappropriation of treatment resources. |

| Seto, M. et al. (2018) [37] | Population extracted from the National Trajectory project (NCRMD patients who entered the mental health review board system (Quebec, Ontario and British Colombia) between 1 May 2000 and 30 April 2005): 50 individuals with an NCRMD finding for a sexual offence at any time were compared with a group of 50 individuals found NCRMD for a violent offence against a person at any time, but who had never committed a sexual offence. N = 100 | Sexual index NCRMD offense, nonsexual violent index NCRMD offense | Historical Factors | Sociodemographic characteristics (age at index NCRMD verdict, gender, education, relationship status, residential status, and employment status prior to the index offence), clinical history, criminal history, mental health review board trajectories, and details of the risk assessments (behavior while under the mandate of mental health review board) and time until reoffending. | NCRMD individuals who committed sex offenses were more likely to lack paid work and were younger at the time of first psychiatric contact compared to violent offenders, but no significant differences were found in most other sociodemographic or psychiatric history aspects. There were no differences between the groups in their first review board disposition or behaviors between hearings, but sex offenders had a longer mean duration under the review board mandate (6.6 years vs. 4.8 years for violent offenders). Despite these differences, no significant differences were found in recidivism hazards, suggesting that review boards may be overly conservative in managing sex offenders, given their low overall recidivism rates. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellerin, J.-C.; Désilets, M.; Borduas Pagé, S.; Hudon, A. Factors Considered for the Assessment of Risk in Administrative Review Boards of Canada: A Scoping Review. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 573-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040039

Pellerin J-C, Désilets M, Borduas Pagé S, Hudon A. Factors Considered for the Assessment of Risk in Administrative Review Boards of Canada: A Scoping Review. Forensic Sciences. 2024; 4(4):573-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040039

Chicago/Turabian StylePellerin, Jane-Caroline, Marie Désilets, Stéphanie Borduas Pagé, and Alexandre Hudon. 2024. "Factors Considered for the Assessment of Risk in Administrative Review Boards of Canada: A Scoping Review" Forensic Sciences 4, no. 4: 573-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040039

APA StylePellerin, J.-C., Désilets, M., Borduas Pagé, S., & Hudon, A. (2024). Factors Considered for the Assessment of Risk in Administrative Review Boards of Canada: A Scoping Review. Forensic Sciences, 4(4), 573-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040039