Linguistic Indicators of Psychopathy and Malignant Narcissism in the Personal Letters of the Austrian Killer Jack Unterweger

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Language and Psychiatric Disorders

1.1.1. Psychopathy

1.1.2. Malignant Narcissism

1.2. Jack Unterweger

- (1)

- Which linguistic features typical of psychopathy can be found in the personal letters of Jack Unterweger to Andrea Wolfmayr?

- (2)

- Which linguistic features typical of malignant narcissism can be found in the personal letters of Jack Unterweger to Andrea Wolfmayr?

2. Data

3. Results

3.1. Methodology

| Condition | Symptom | Description/Definition | Linguistic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychopathy | Manipulation | “mak[ing] others believe or do things that are in the interest of the manipulator and against the best interests of the manipulated” [62] | Speech acts (e.g., [94,95]) Cause-and-effect statements [53,65] |

| Lack of empathy | “Conscious attention to the feelings of another person” [101] | Point of view (Kann, 2017) Emotion words (e.g., [103]) | |

| Psychological distancing | “transcend[ing] […] ego-centric point of view” [110] | Decreased 1PP, increased 3PP, proper nouns, hedging (e.g., [56,57,58,59]) | |

| Lack of coherence, quick changes of topics | Coherence: “an intrinsic property of discourse reflecting its semantic and pragmatic unity” [111] | Syntactic non-coherence: “lack of formal agreement blocking a potential cross-reference, discrepancies of polysemy or homonymy, discrepancy between referential and metalinguistic meanings, shifts in genericity, violation or normal patterns of placement of old or new information interpreted as a shift of referent, and an unmotivated shift in style” [107] Pragmatic non-coherence: “shift of referent, appearing as a time shift, and explicit or implicit contradiction” [107] | |

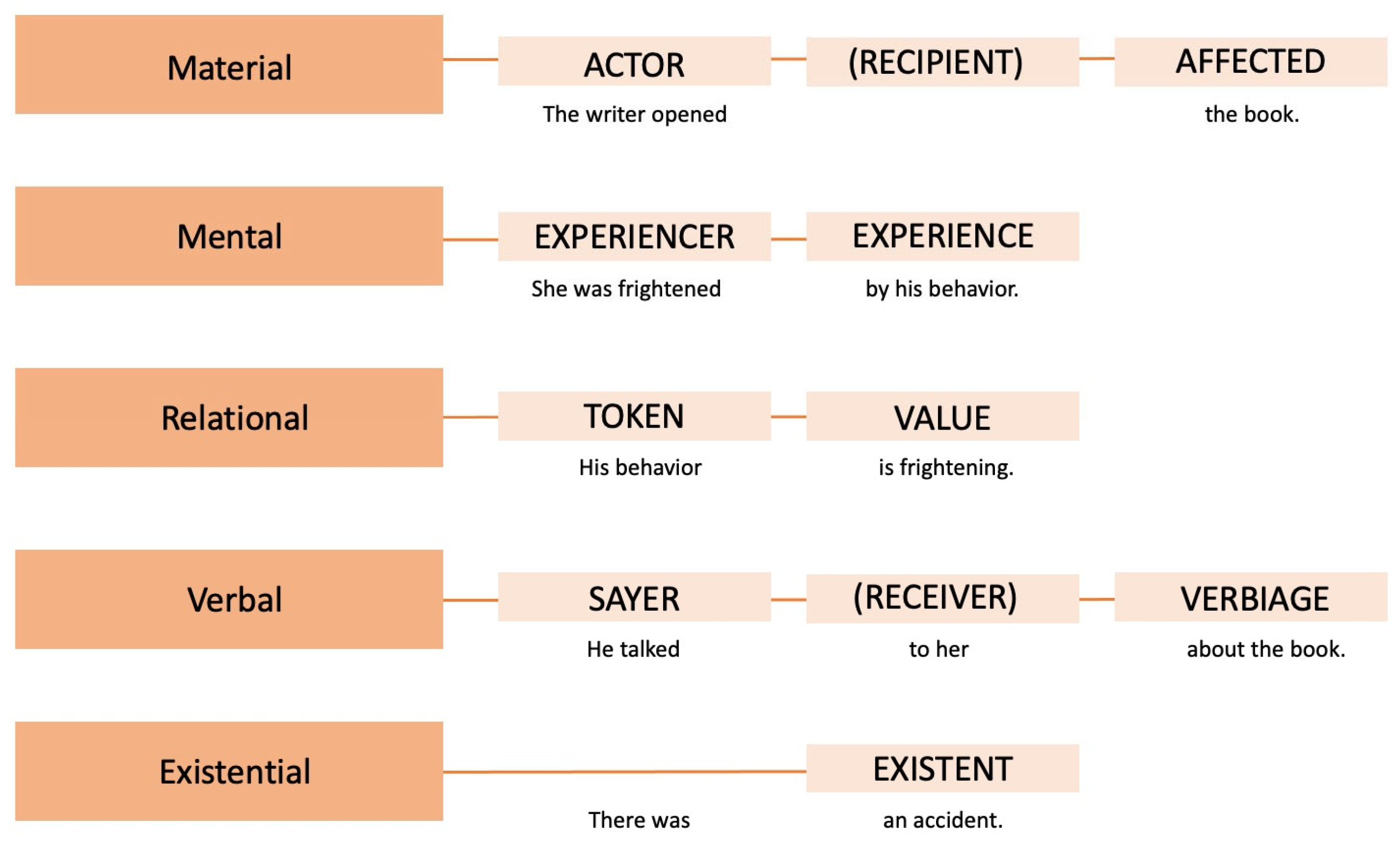

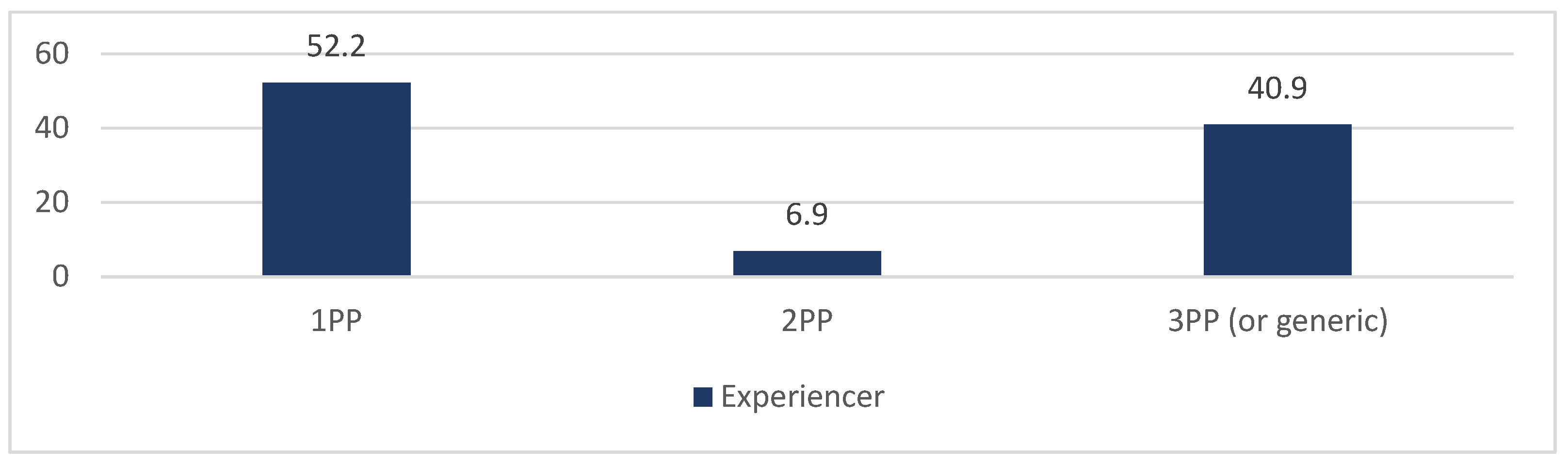

| Malignant narcissism | Self- and other presentation | 1PP, 2PP, 3PP, transitivity | |

| Swear words | Taboo words with both literal and non-literal meanings, and an emotional or attitudinal dimension [109]) | ||

| Lack of sensory and perceptual processes | Transitivity: mental processes |

Transitivity Analysis

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Limitations

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Psychopathy

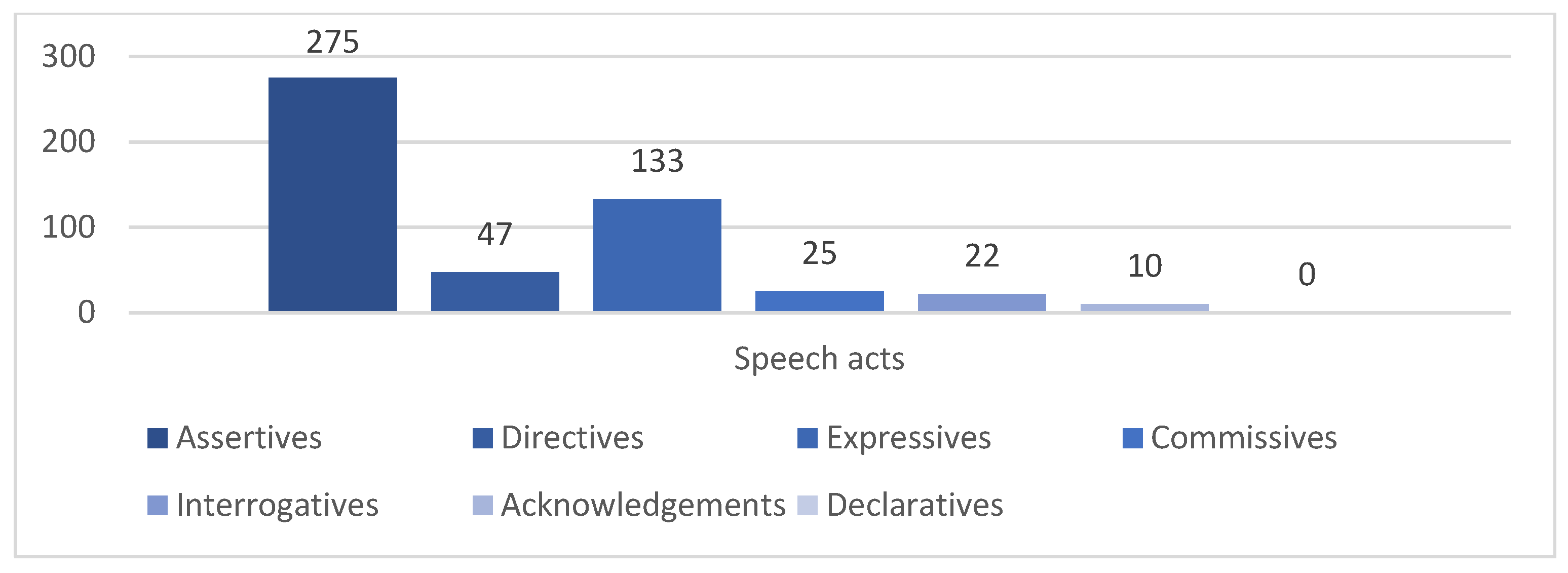

4.1.1. Manipulation

4.1.2. Empathy

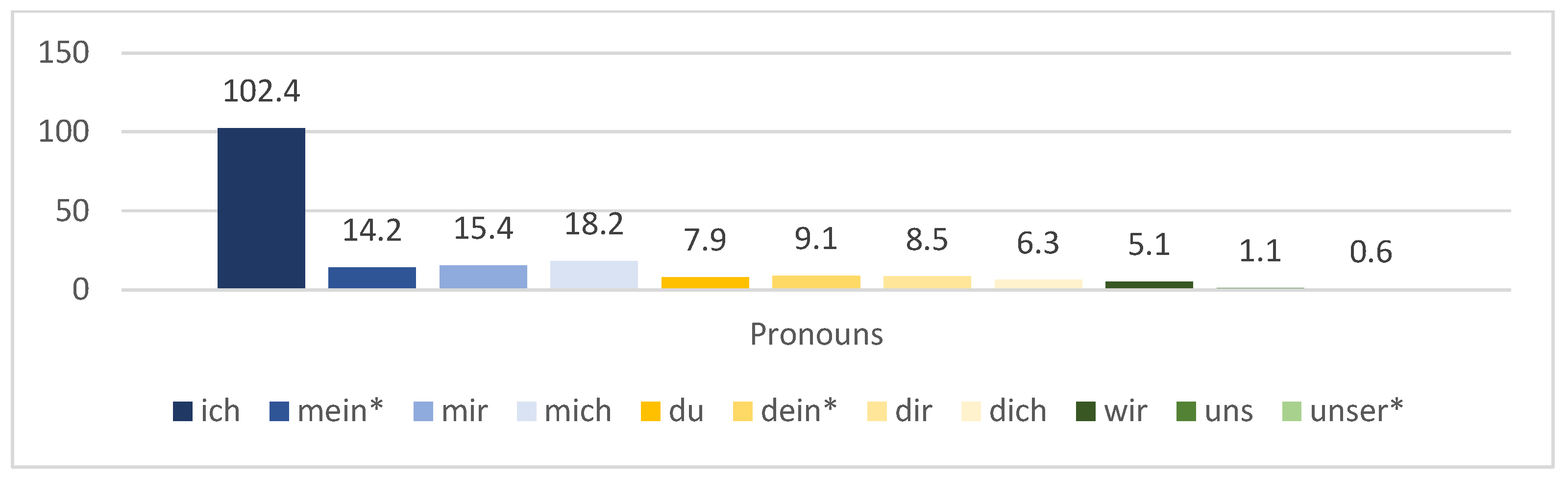

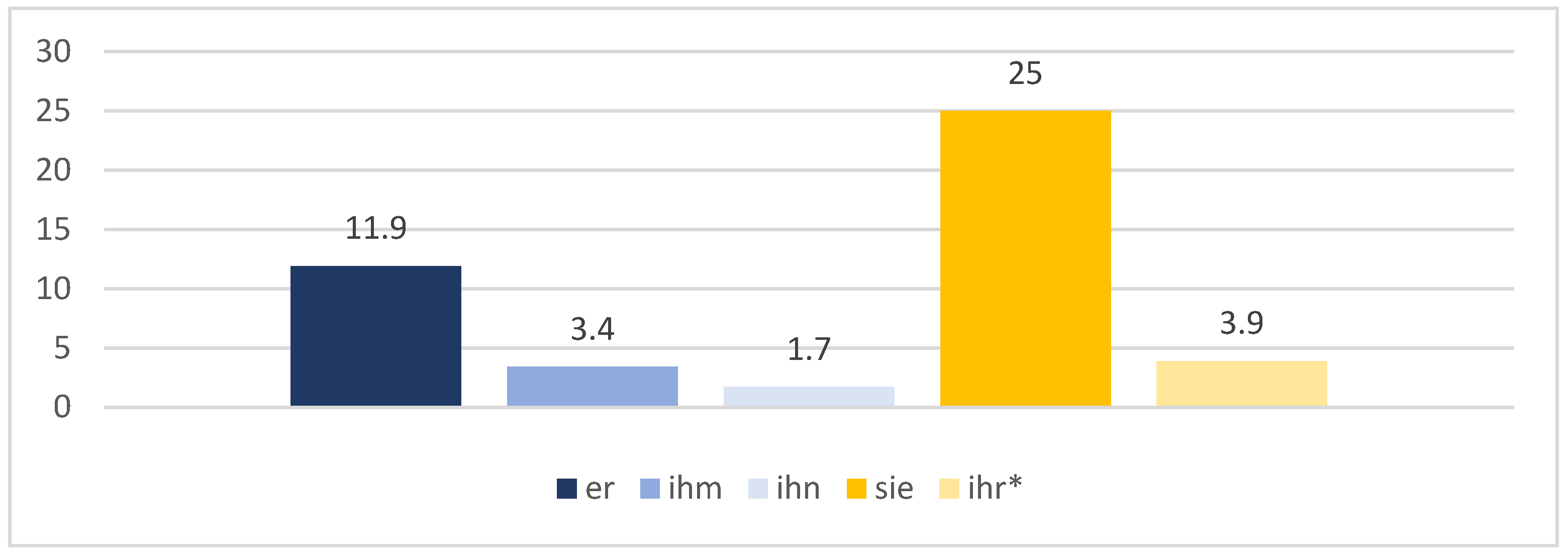

4.1.3. Psychological Distancing

4.1.4. Coherence

4.2. Malignant Narcissism

4.2.1. Self- and Other Presentation

4.2.2. Swear Words

4.2.3. Sensory and Perceptual Processes (Transitivity)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ehrhardt, S. Authorship Attribution Analysis. In Handbook of Communication in the Legal Sphere; Visconti, J., Rathert, M., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Nini, A. Developing forensic authorship profiling. Lang. Law Ling. Direito 2018, 5, 38–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fobbe, E. Author Identification. In Language as Evidence. Doing Forensic Linguistics; Guillén-Nieto, V., Stein, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M.; Grant, T. Killer stance: An investigation of the relationship between attitudinal resources and psychological traits in the writings of four serial murderers. Lang. Law Ling. Direito 2022, 9, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L.; Schwarty, S.; Knafo, A. The Big Five personality factors and personal values. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; King, L.A. Linguistic styles: Language use as an individual difference. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1296–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Williams, K.M. The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 2002, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Richards, S.; Paulhus, D. The dark triad of personality: A 10 year review. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.; Geis, F.L. Studies in Machiavellianism; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. Toward a taxonomy of dark personalities. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.; Gupta, R.; Jones, D. Dark or disturbed?: Predicting aggression from the Dark Tetrad and schizotypy. Aggress. Behav. 2021, 47, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.G.; Albertson, E.; Verona, E. Dark and vulnerable personality trait correlates of dimensions of criminal behavior among adult offenders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.T.; Rice, M.E.; Cormier, C.A. Psychopathy and violent recidivism. Law Hum. Behav. 1991, 15, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-García, A.; Gesteira, C.; Sanz, J.; García-Vera, M. Prevalence of psychopathy in the general adult population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Incarceration Nation. APA 2014, 45, 56. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/10/incarceration (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Hare, R. Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths among Us; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, J. Language in Psychiatry. A Handbook of Clinical Practice; Equinox Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R.D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brites, J.; Ladera, V.; Perea, V.; García, R. Verbal functions in psychopathy. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2014, 59, 1536–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, J.T.; Woodworth, M.; Boochever, R. Psychopaths online: The linguistic traces of psychopathy in email, text messaging and Facebook. Media Commun. 2018, 6, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogolyubova, O.; Panicheva, P.; Tikhonov, R.; Ivanov, V.; Ledovaya, Y. Dark personalities of Facebook: Harmful online behaviors and language. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C. Narcissism on Facebook: Self-promotional and anti-social behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, C.; Byers, A.; Boochever, R.; Park, G. Predicting Dark Triade Personality Traits from Twitter usage and a linguistic analysis of tweets. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications ICMLA, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 12–15 December 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Zum “Brief” über den “Humanismus”. Heidegger Stud. 2010, 26, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Language and Mind, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, T.; Luo, J. Mining the Relationship between Emoji Usage Patterns and Personality. In Proceedings of the 12th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 25–28 June 2018; pp. 648–651. [Google Scholar]

- Marko, K. “Depends on who I’m writing to”—The influence of addressees and personality traits on the use of emoji and emoticons, and related implications for forensic authorship analysis. Front. Commun. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J. The Secret Life of Pronouns; Bloomsbury: Dexter, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rude, S.; Gortner, E.-M.; Pennebaker, J. Language use of depressed and depressed-vulnerable college students. Cogn. Emot. 2004, 18, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillars, A.; Shellen, W.; McIntosh, A.; Pomegranate, M. Relational characteristics of language: Elaboration and differentiation in marital conversations. West. J. Commun. 1997, 61, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleckley, H. The Mask of Sanity. An Attempt to Reinterpret the So-Called Psychopathic Personality; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). 2022. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Babiak, P.; Neumann, C.; Hare, R. Corporate psychopathy: Talking the walk. Behav. Sci. Law 2010, 28, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, R.J. Neurobiological basis of psychopathy. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 182, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brito, S.; Forth, A.; Baskin-Sommers, A.; Brazil, I.; Kimonis, E.; Pardini, D.; Frick, P.; Blair, R.; Viding, E. Psychopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, R.; Neumann, C. Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.; Skilling, T.; Rice, M. The construct of psychopathy. Crime Justice Rev. Res. 2001, 28, 197–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, D.; Gudonis, L. The development of psychopathy. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viding, E.; McCrory, E.; Seara-Cardoso, A. Psychopathy. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R871–R874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/4298 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Cooke, D. Psychopathic Personality Disorder. In The Cambridge Handbook of Forensic Psychology; Brown, J., Horwath, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 369–387. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, K. The Wisdom of Psychopaths; Arrow Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R.D.; Harpur, T.J.; Hakstian, A.R.; Forth, A.E.; Hart, S.D.; Newman, J.P. The revised Psychopathy Checklist: Reliability and factor structure. Psychol. Assess. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 2, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S. Cohesion and Coherence in the Speech of Psychopathic Criminals. Ph.D. Thesis, British Columbia University, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Viding, E. Psychopathy. A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gullhaugen, A.S.; Sakshang, T. What can we learn about psychopathic offenders by studying their communication? A review of the literature. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2019, 48, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinke, L.T.; Porter, S.; Korva, N.; Fowler, K.; Lilienfeld, S.O.; Patrick, C.J. An examination of the communication styles associated with psychopathy and their influence on observer impressions. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2017, 41, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.H.; Gervais, M.M.; Fessler, D.; Kline, M. Subclinical primary psychopathy, but not physical formidability or attractiveness, predicts conversational dominance in a zero-acquaintance situation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimé, B.; Bouvy, H.; Leborgne, B.; Rouillon, F. Psychopathy and nonverbal behavior in an interpersonal situation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1978, 87, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitchford, B.; Arnell, K.M. Speech of young offenders as a functions of their psychopathic tendencies. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2019, 73, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, J. The language of psychopaths: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 27, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Woodworth, M.; Porter, S. Hungry like the wolf: A word-pattern analysis of the language of psychopaths. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2013, 18, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleckley, H. The Mask of Sanity: An Attempt to Clarify Some Issues about the So-Called Psychopathic Personality; Mosby, Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, M.; Obler, L.; Albert, M.; Helm-Easterbrooks, N. Empty speech in alzheimer’s disease and fluent aphasia. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1985, 28, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Ayduk, O. Self-Distancing: Theory, Research, and Current Directions. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Olson, J.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 81–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Bruelman-Senecal, E.; Park, J.; Burson, A.; Dougherty, A.; Shablack, H.; Bremner, R.; Moser, J.; Ayduk, O. Self-talk as a regulatory mechanism: How you do it matters. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahane, A.D.; Denny, B.T. Predicting emotional health indicators from linguistic evidence of psychological distancing. Stress Health 2018, 35, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ayduk, Ö.; Kross, E. Stepping back to move forward: Expressive writing promotes self-distancing. Emotion 2016, 16, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R. Without Conscience. The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths among Us; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Le, M.; Woodworth, M.; Gillman, L.; Hutton, E.; Hare, R. The linguistic output of psychopathic offenders during a PCL-R interview. Crim. Justice Behav. 2017, 44, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, T. Discourse and manipulation. Discourse Soc. 2006, 17, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillat, D.; Oswald, S. Defining manipulative discourse: The pragmatics of cognitive illusions. Int. Rev. Pragmat. 2009, 1, 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussure, L. Manipuation and Cognitive pragmatics: Preliminary Hypotheses. In Manipulation and Ideologies in the 20th Century: Discourse, Language, Mind; de Saussure, L., Schulz, P., Eds.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 113–145. [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth, M.; Porter, S. In cold blood: Characteristics of criminal homicides as a function of psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2002, 111, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, K.; Joinson, A.; Cotterill, R.; Dewdney, N. Characterizing the linguistic chameleon: Personal and social correlates of linguistic style accommodation. Hum. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrij, A. Detecting Lies and Deceit; Wiley: Cornwall, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harem R., D.; Neumann, C.S. The role of antisociality in the psychopathic construct. Comment on Skeem and Cooke (2010). Psychol. Assessment. 2010, 22, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, R.D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised; Multi-Health Systems: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gawda, B. The differentiation of narrative styles in individuals with High Psychopathic Deviate. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2022, 51, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzenweger, M.; Clarkin, J.; Caligor, E.; Cain, N.; Kernberg, O. Malignant narcissism in relation to clinical change in borderline personality disorder: An exploratory study. Psychopathology 2018, 51, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glad, B. Why tyrants go too far: Malignant narcissism and absolute power. Political Psychol. 2002, 23, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, R. Malignant narcissism and sexual homicide—Exemplified by the Unterweger case. Arch. Kriminol. 1999, 204, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Houlcroft, L.; Bore, M.; Munro, D. Three faces of narcissism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, E.; Shedler, J.; Bradley, R.; Westen, D. Refining the construct of narcissistic personality disorder: Diagnostic criteria and subtypes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, R. A Study of Malignant Narcissism: Personal and Professional Insights; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernberg, O.F. Severe Personality Disorders; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Goldner-Vukov, M.; Moore, L.J. Malignant narcissism: From fairy tales to hash reality. Psychiatr. Danub. 2010, 22, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Craig, R.; Amernic, J. Detecting linguistic traces of destructive narcissism at-a-distance in a CEO’s letter to shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, S.; Bergman, S.; Bergman, J.; Fearrington, M. Twitter versus Facebook: Exploring the role of narcissism in the motives and usage of different social media platforms. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, A.; Küfner, A.; Deters, F.; Donnellan, M.; Brucks, M.; Holtzman, N.; Back, M.; Pennebaker, J.; Mehl, M. Narcissism and the use of personal pronouns revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, e1–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, N.; Tackman, A.; Carey, A.; Brucks, M.; Küfner, A.; Deters, F.; Back, M.; Donnellan, M.; Pennebaker, J.; Sherman, R.; et al. Linguistic markers of grandiose narcissism: A LIWC analysis of 15 samples. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 38, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, J. Der Mann aus dem Fegefeuer; Heyne: Munich, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, E.; Reibenwein, M. Jack Unterweger: Der Popstar unter den Serienmördern. Kurier. 29 January 2022. Available online: https://kurier.at/chronik/oesterreich/jack-unterweger-der-popstar-unter-den-serienmoerdern/401888249 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Busch, V. Jack Unterweger. In Psychologie des Guten und Bösen; Frey, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, W. Der Fall Jack Unterweger. Worte und Taten. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 16 August 2020. Available online: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/panorama/jack-unterweger-moerder-oesterreich-literatur-1.4898159 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Widler, Y. Psychiater Haller: “Gefährlich ist nicht der finstere Wald, sondern das eigene Heim”. Kurier. 6 October 2019. Available online: https://kurier.at/chronik/oesterreich/profiler-haller-gefaehrlich-ist-nicht-der-finstere-wald-sondern-das-eigene-heim/400637114 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Garfield, D.; Havens, L. Paranoid phenomena and pathological narcissism. Am. J. Psychother. 1991, 45, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, C. Emotion and psychopathy: Startling new insights. Psychophysiology 1994, 31, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfmayr, A. Jack Und Ich. Das Böse in Mir; Edition Keiper: Graz, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J. How to Do Things with Words; Claredon: Oxford, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, J. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, T.; MacLeod, N. Language and Online Identities. The Undercover Policing of Internet Sexual Crime; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sorlin, S. Language and Manipulation in House of Cards; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlichenko, L. Manipulative pragmatics of interrogation. Cogito Multidiscip. Res. J. 2021, 13, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R.; Bohart, A.C.; Watson, J.C.; Greenberg, L.S. Empathy. In Psychotherapy Relationships that Work; Norcross, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 132–152. [Google Scholar]

- Decety, J.; Lamm, C. Empathy Versus Personal Distress: Recent Evidence from Social Neuroscience. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Goubert, L.; Craig, K.D.; Buysee, A. Perceiving Others in Pain: Experimental and Clinical Evidence of the Role of Empathy. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S. Empathic Processing: Its Cognitive and Affective Dimensions and Neuroanatomical Basis. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N.; Eggum, N.D. Empathic Responding: Sympathy and Personal Distress. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gladkova, A. Sympathy, compassion, and empathy in English and Russian: A linguistic and cultural analysis. Cult. Psychol. 2010, 16, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, T. Measuring Linguistic Empathy: An Experimental Approach to Connecting Linguistic and Social Psychological Notions of Empathy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kousta, S.; Vinson, D.; Vigliocco, G. Emotion words, regardless of polarity, have a processing advantage over neutral words. Cognition 2009, 112, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.; Ashokkumar, A.; Seraj, S.; Pennebaker, J. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC-22; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.liwc.app (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Hyland, K. Metadiscourse. Exploring Interaction in Writing; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting, J. Pragmatics and Discourse; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Enkvist, N.E. Coherence, Pseudo-Coherence, and Non-Coherence. In Cohesion and Semantics; Östman, I.O., Ed.; Abo Akademi Foundation: Abo, Finland, 1978; pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson, H.G. Discourse Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, M. ‘Don’t say crap. Don’t use swear words.’—Negotiating the use of swear/taboo words in the narrative mass media. Discourse Context Media 2019, 29, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Ayduk, O. Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnik, A.; Bastiaanse, R.; Stede, M.; Khudyakova, M. Linguistic mechanisms of coherence in aphasic and non-aphasic discourse. Aphasiology 2022, 36, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K. An Introduction to Functional Grammar; Hodder Arnold: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, C. An Introduction to Functional Grammar; Hodder Arnold: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, L.V. “Justice demands that you find this man not guilty”: A transitivity analysis of the closing arguments of a rape case that resulted in a wrongful conviction. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 28, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, P. Writing up or writing of crimes of domestic violence? A transitivity analysis of police reports. Lang. Law Ling. Direito 2021, 8, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, K. The presentation of voices, evidence, and participant roles in Austrian courts—A case study on a record of court proceedings. Int. J. Lang. Law 2019, 8, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K. Functional Grammar; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goatly, A.; Hiradhar, P. Critical Reading and Writing in the Digital Age; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- University of Manchester (n.d.). Expressing Cause and Effect. Available online: https://www.languagecentre.manchester.ac.uk/resources/online-resources/online-skills-development/academic-english/academic-writing/expressing-cause-and-effect/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Holtgraves, T. Language structure in social interaction: Perceptions of direct and indirect speech acts and interactants who use them. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevala, M.; Palander-Collin, M. Letters and letter writing: Introduction. Eur. J. Engl. Stud. 2005, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, S. Schattenseiten des Mitgefühls. Spektrum Wiss. Gehirn Geist 2017, 9, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D. The multi-dimensional approach to linguistic analyses of genre variation: An overview of methodology and findings. Comput. Humanit. 1992, 26, 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P. Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis; Continuum: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DWDS Soldatenbriefe (n.d.). Soldatenbriefe (1745–1872). Available online: https://www.dwds.de/d/korpora/soldatenbriefe (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environments for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (n.d.). Post Nach Drüben. Briefe Aus Dem DDR-Corpus. Available online: http://telota.bbaw.de/pvd/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- DWDS Kernkorpus (n.d.). DWDS-Kernkorpus (1900–1999). Available online: https://www.dwds.de/d/korpora/kern (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Trutkowski, E. Topic Drop and Null Subjects in German; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duguine, M. Reversing the approach to null subjects: A perspective from language acquisition. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liceras, J.; Díaz, L. Topic-drop versus pro-drop: Null subjects and pronominal subjects in the Spanish L2 of Chinese, English, French, German and Japanese speakers. Second. Lang. Res. 1999, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabon, D.; Champan, T. Investigative Discourse Analysis; Carolina Academic Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, G. The Pragmatics of Politeness; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herwig, M. JACK. Gier Frisst Schönheiten. NDR Podcast. 2022. Available online: https://www.ardaudiothek.de/sendung/jack-gier-frisst-schoenheiten/10385179/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Kemper, S. Life-span changes in syntactic complexity. J. Gerontol. 1987, 42, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A. Language style as audience design. Lang. Soc. 1984, 13, 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alfonso, S. AI in Mental Health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Text Type | Size (Words) |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Letter | 683 |

| 1984 | Letter | 83 |

| 1984 | Christmas card | 34 |

| 1985 | Postcard | 24 |

| 1985 | Letter | 1643 |

| 1985 | Letter | 369 |

| 1985 | Birthday card | 7 |

| 1986 | Letter | 956 |

| 1986 | Letter | 542 |

| 1987 | Postcard | 82 |

| 1988 | Birthday card | 19 |

| 1989 | Letter | 122 |

| 1990 | Letter | 227 |

| 1990 | Letter | 724 |

| TOTAL: | 5515 |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | bin leider noch nicht zum Lesen gekommen da ich unbedingt lernen musste | haven’t had the time to read it yet because I desperately needed to study |

| (2) | Ich muss auch ans Geldverdienen denken, Lesungen machen und jetzt sozusagen noch kurbeln, dass ich für Juni und Anfang Juli noch Leseeinladungen erhalte! | I have to think about earning money, do readings and some toiling to make sure that I receive invitations for readings in June and at the beginning of July! |

| (3) | wenn er dann weitertratscht steht er lächerlich da, | if he then retells [the story] he will seem ridiculous, |

| (4) | Und mein Freizeitspaß, je nach Laune, geht er mir aufn Wecker, frag ich solche Blödheiten, weil er dann abhaut, bin ich mal gut aufgelegt, erzähl ich dem das Innenleben der Hure und ihren Kunden in Einzelheiten, die ich selbst nicht kenne…aber dann sind die glücklich und mich können sie dort wo ich nach dem Durchfall eh nicht hinkomm. | And for fun in my free time, depending on the mood, is he annoying me, I ask such stupidities, because he will then go away, if I’m in a good mood, I tell him about the inner life of the whore and her clients in detail, which I don’t know myself… but then they are happy and they can shove it where I can’t reach after the diarrhea anyways. |

| (5) | Heft 9 wird Ende Mai/Anfang Juni erscheinen, wenn nichts passiert, bzw, ich die finanz. Rückendeckung zusammenbringe. | Volume 9 will appear at the end of May/beginning of June, if nothing happens, and if I manage to build up financial reserves. |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (6) | bei sachlicher und rationaler Abwicklung, Punkt für Punkt, kann nichts passieren | with factual and rational handling, point by point, nothing can happen |

| (7) | Die selbstgewählte Isolation vom Tagesgeschehen im Knast hat sich gelohnt, | The self-imposed isolation from events of the day in prison have paid off, |

| (8) | [ich] halte mir zugute, etwas dafür getan zu haben. | [I] grant myself that I have done something for it. |

| (9) | nichts in den letzten Jahren war umsonst! | nothing in the past years has been in vain! |

| (10) | Vergiss bei all dem nie, wichtig ist die Ichperson, die Selbstbestätigung, solange Du immer wieder versuchst, so zu sein, wie es andere gerne hätten, […] wirst immer nur Marionette sein, | Never forget in all of this, important is the I-person, the self-affirmation, as long as you keep trying, to be, as others would like you to be, […] you will always only be marionette-like, |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (11) | tummel dich mit deinem esoterischen Buch | hurry up with your esoteric book |

| (12) | bis Dez. 85 schick/Texte!! | until Dec. 85 send/texts!! |

| (13) | behalte es, wenn Dus gut findest, Du stark genug bist, schicke es weg, | keep it, if you like it, if you are strong enough, send it off |

| (14) | Schreibe mit Herz, ohne Hemmungen. | Write with heart, without inhibitions |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (15) | am besten, ich krieg eine Telefonnummer und rufe zurück, | it‘s best if I receive a phone number and call back, |

| (16) | Unter der Telefonnummer: XXXXX (Bürozeiten) kann man mich entweder ab Anfang Juni erreichen, bzw, erfahren, wo ich erreichbar bin. | Under the phone number: XXXXX (office hours) one can reach me either at the beginning of June or find out where I can be reached. |

| (17) | les ich bald mal wieder was?! | will I read something again soon?! |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (18) | ich akzeptiere es vollkommen wenn jemand den Kontakt in Zukunft mit dem FREIGELASSENEN Jack Unterweger abbricht, weiterhin nur schriftlich, telefonisch aufrechterhält. | I completely accept it if someone breaks off the contact with the RELEASED Jack Unterweger in the future, keeps it only in written or by telephone. |

| (19) | Ich kenne Menschen (Nachbarngetuschel) zu gut, und verstehe jede Haltung. | I know people (whispering neighbors) too well, and understand every attitude. |

| (20) | Aber ich weiß, Du willst was anderes sagen, ich versteh Dich und steh da etwas ratlos rum | However, I know you want to say something different, I understand you and stand by baffled |

| (21) | Ich versteh Dich ganz gut. | I understand you very much. |

| (22) | dass ich ein Typ bin, der sich unbewusst sofort auch in den anderen hinein zu denken versucht, | that I am a type who immediately subconsciously tries to put himself into others’ shoes, |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (23) | …hab soeben mit einem, 21, schluß gemacht, bin ein jahrmit ihm…die mutti versteht sich gut mit ihm… aber nun fing der an von verlobung und zusammenleben zu reden… da fiel mir auf, wie fad und gewöhnlich der im grunde ist… | …have just broken up with someone, 21, was with him a year… mom gets along well with him…but he now began to talk about engagement and living together… that is when I noticed how boring and ordinary he actually is… |

| (24) | schön auch, wenns euch selbst gefallen hat. | great, if you yourselves liked it. |

| (25) | nur weil sie eben was erfahren wollen | just because they want to find out something |

| (26) | aber dann sind die glücklich | but then they are happy |

| (27) | ihm die Schönheit meiner Lotosblüte schenken… | give him the beauty of my lotos flower… |

| (28) | lieber nicht zuviel erwarten, dann freuen oder nicht enttäuscht sein. | better not to expect too much, then look forward to it or nor not be disappointed. |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (29) | weil man ja weiterdenkt, wie gings weiter… | because one thinks ahead, how did it go on… |

| (30) | [sie] wollten dafür zwei Geschichten vom Autor JU | [they] wanted to have two stories by author JU |

| (31) | Aber für die ist es eben exotisch wie ein Häfenbruder das alles und dazu viele gute Menschen erreichen kann aus seiner Lage… | However, for them it is exotic how a jailbird does all this and reaches so many good people from his position… |

| (32) | dass es einen Unterschied macht, dem Häftling zu schreiben, ihn im Knast zu besuchen oder in Freiheit zu begegnen… | that it makes a difference to write to the inmate, visit him in jail or encounter [him] in freedom |

| (33) | wenn jemand den Kontakt in Zukunft mit dem FREIGELASSENEN Jack Unterweger abbricht, | and if someone breaks off the contact with the RELEASED Jack Unterweger in the future |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (34) | Und was mir nicht zusagt, auch von der Aussage her falsch ist, sich aber immer wieder findet, warum wohl, um zu zeigen, schaut, ich bin anständig,-… | Additionally, what I do not like, also is wrong, but reoccurs throughout, I wonder why, to show, see, I am decent,-… |

| (35) | Zu Dir, diesem Buch, was ich dazu, kurz nur, ich las es weniger als Kritiker, für mich war es ein Buch einer Person, die mich akzeptiert… | About you, the book, what I, only briefly, I read it less as a critic, for me it was a book of a person, who accepts me… |

| (36) | Ein anderes, wenn Du es auch als bereinigt ansiehst, Problem (…) | A different, even if you view it as solved, problem (…) |

| (37) | unbewusst, 58 bis 62 lebten wir in einem Zimmer…jetzt las sie was in der Zeitung…fragte…Erinnerung. | subconscious, 58 until 62 we lived in one room…now she read something in the paper…asked…memories. |

| (38) | höre neben dem Briefeschreiben gerade, Gedanken, Marylin Monroe [sic], nackt sah ich wie jedes andre Mädchen aus… | hear while writing letters just now, thoughts, Marylin Monroe [sic], naked I looked like any other girl… |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (39) | Inzwischen habe ich mit dem Mädchen, so groß wie ich, schlank, sieht eher wie 18 aus, sehr realistisch, selbstbewusst, erfahren in fast allen Lagen, auch Liebschaften (…hab soeben mit einem, 21, schluss gemacht, bin ein jahrmit ihm…die mutti versteht sich gut mit ihm… aber nun fing der an von verlobung und zusammenleben zu reden… da fiel mir auf, wie fad und gewöhnlich der im grunde ist…), eine schöne Beziehung, konnte ihr, nachdem ich mehr von ihr weiß, auch FEGEFEUER schicken, damit sie sieht, was Alkohol ausmacht im Leben, denn sie trinkt ganz gern bei Problemen…, etc., und auch, die Mutter, ein lieber Mensch, aber, wie soll ich sagen, schwach, auf jeden Fall zu schwach für dieses Mädchen. | In the meantime I have with the girl, as tall as I, slim, looks more like 18, very realistic, self-confident, experienced in all areas, also romantic involvements (…have just broken up with someone, 21, was with him a year… mom gets along well with him…but he now began to talk about engagement and living together… that is when I noticed how boring and ordinary he actually is…), a good relationship, was able to, now that I know more about her, send FEGEFEUER, so that she sees what alcohol does in life, because she likes to drink when she has problems…, etc., and also, the mother, a nice person, but, how should I say it, weak, in any case too weak for this girl. |

| (40) | Deshalb nicht enttäuscht, böse sein, wenn ich aufgrund all dieser Turbulenzen (Wohnungsfrage klären, Amtswege; einkaufen; von der Unterhose bis zum Kochgeschirr, Möbel, etc, und tausend andere Alltäglichkeiten, die erledigt werden müssen) ab sofort und wie ich es einschätze bis etwa Mitte Juni, um den 10. Juni will ich alles geschafft haben und mich dann endlich auf Menschen, Begegnungen (Tochter, Schwiegersohn, Enkelkinder, Bekannte, wichtige Gespräche wegen Arbeiten, Literatur, Lesungen) konzentrieren. | Hence, do not be disappointed, mad, if because of all these turbulences I (finding an apartment, taking care of official matters; shopping; from the underpants to the dishes, furniture, etc, and thousand of other banalities that have to be done) from now own and how I estimate it until the mid of June, around the 10th of June I want to have finished everything and can finally concentrate on people, encounters (daughter, son-in-law, grandchildren, acquaintances, important conversations about work, literature, readings). |

| German | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (41) | wird hier ungeniert gesprochen, bzw geschrieben | here one speaks or writes unashamedly |

| (42) | warum schreibt sie so umständlich „schlafen“ | why does she so inconveniently write „sleeping“ |

| (43) | überall die Andrea → nur sie schweigt…?! | Andrea is everywhere → only she is silent…?! |

| (44) | verpflichtet aber die Andrea nicht zur Rechenschaft! | but does not oblige Andrea to accountability! |

| (45) | hier wieder eine völlig andere Andrea | here again a completely new Andrea |

| (46) | anrufen kann man mich immer | I can always be called [on the phone] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marko, K.; Leibetseder, I. Linguistic Indicators of Psychopathy and Malignant Narcissism in the Personal Letters of the Austrian Killer Jack Unterweger. Forensic Sci. 2023, 3, 45-68. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci3010006

Marko K, Leibetseder I. Linguistic Indicators of Psychopathy and Malignant Narcissism in the Personal Letters of the Austrian Killer Jack Unterweger. Forensic Sciences. 2023; 3(1):45-68. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci3010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarko, Karoline, and Ida Leibetseder. 2023. "Linguistic Indicators of Psychopathy and Malignant Narcissism in the Personal Letters of the Austrian Killer Jack Unterweger" Forensic Sciences 3, no. 1: 45-68. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci3010006

APA StyleMarko, K., & Leibetseder, I. (2023). Linguistic Indicators of Psychopathy and Malignant Narcissism in the Personal Letters of the Austrian Killer Jack Unterweger. Forensic Sciences, 3(1), 45-68. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci3010006