Has the Lack of a Unified Halal Standard Led to a Rise in Organised Crime in the Halal Certification Sector?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“O mankind, eat from whatever is on earth [that is] lawful and good and do not follow the footsteps of Satan. Indeed, he is to you a clear enemy.”(Quran 2:168)

“O you who have believed, eat from the good things which We have provided for you and be grateful to Allah if it is [indeed] Him that you worship.”(Quran 2: 172)

“He has only forbidden to you dead animals, blood, the flesh of swine, and that which has been dedicated to other than Allah. But whoever is forced [by necessity], neither desiring [it] nor transgressing [its limit], there is no sin upon him. Indeed, Allah is Forgiving and Merciful.”(Quran 2: 173)

2. Lawmakers, Islam, and Animal Welfare

2.1. European Lawmakers and Animal Welfare

2.2. Animal Welfare in the Holy Quran

Animal Welfare in Traditions about the Prophet (Sunnah)

“The Prophet passed by a man who was dragging a sheep by its ear. He said: “Leave its ear alone and hold it by the sides of its neck.”Sunan Ibn Majah

“The Prophet forbade (animals to be beaten) on the face or branded on the face. ”Sahih Muslim

“It is reported that it is disliked animals being made to fight each other.”Sahih al-Bukhari

“The Prophet forbade killing any animal when it is tied up (for use as a target).”Sunan Ibn Majah

2.3. Regarding Animal Treatment during Slaughtering

The Prophet said: “Allah has decreed that everything should be done in a good way, so when you kill, use a good method.”Sunan Abi Dawud

“Another hadith in which the Messenger of Allah forbade the devil’s sacrifice (cruel slaughter). This refers to the slaughtered animal whose skin is cut off, and is then left to die without its jugular veins being severed.”Sunan Abi Dawud

2.4. Regarding Punishment and Reward for Dealing with Animals

“A person was suffering from intense thirst while on a journey, when he found a well. He climbed down into it and drank (water), and then came out and saw a dog with its tongue hanging out due to thirst and eating the moistened earth. The person said: “This dog has suffered from thirst as I suffered from it.” He climbed down into the well, filled his shoe with water, then held it in his mouth until he climbed up and made the dog drink it. So Allah appreciated this act of his and pardoned him. Then (the companions around him) said: “Allah’s Messenger, is there a reward for us even for (serving) such animals?” He said: “Yes, there is a reward for service to every living animal.”Sahih Muslam

“The Prophet said: “A woman entered the (Hell) Fire because of a cat which she had tied, neither giving it food nor setting it free to eat from the vermin of the earth.”Sahih al-Bukhari

“The Prophet said: “It is a great sin for man to imprison those animals which are in his power.”Sahih Muslim

2.5. About Cutting a Body Part from a Live Animal

“The Prophet said: “Cursed is the one who did muthla to an animal (i e. cut its limbs or some other part of its body while still alive).”Sahih al-Bukhari

“The Prophet said: “Whatever is cut from an animal when it is still alive, what is cut from it is maitah (dead meat).”Sunan Ibn Majah

3. Halal Food from a Religious Perspective

4. Halal Certification Bodies (HCBs)

Halal Accreditation Bodies (HABs)

- American Association for Laboratory Accreditation (A2LA)

- International Emirates Accreditation Center (EIAC)

- National Council for Accreditation Egypt (EGAC).

- Entidad Nacional de Acreditación—Spain (ENAC)

- Emirates National Accreditation System (ENAS)

- GCC Accreditation Center (GAC)

- Joint Accreditation System of Australia and New Zealand (JAS-ANZ),

- Pakistan National Accreditation Council (PNAC)

- Saudi Accreditation Committee (SAC)

- United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UKAS)

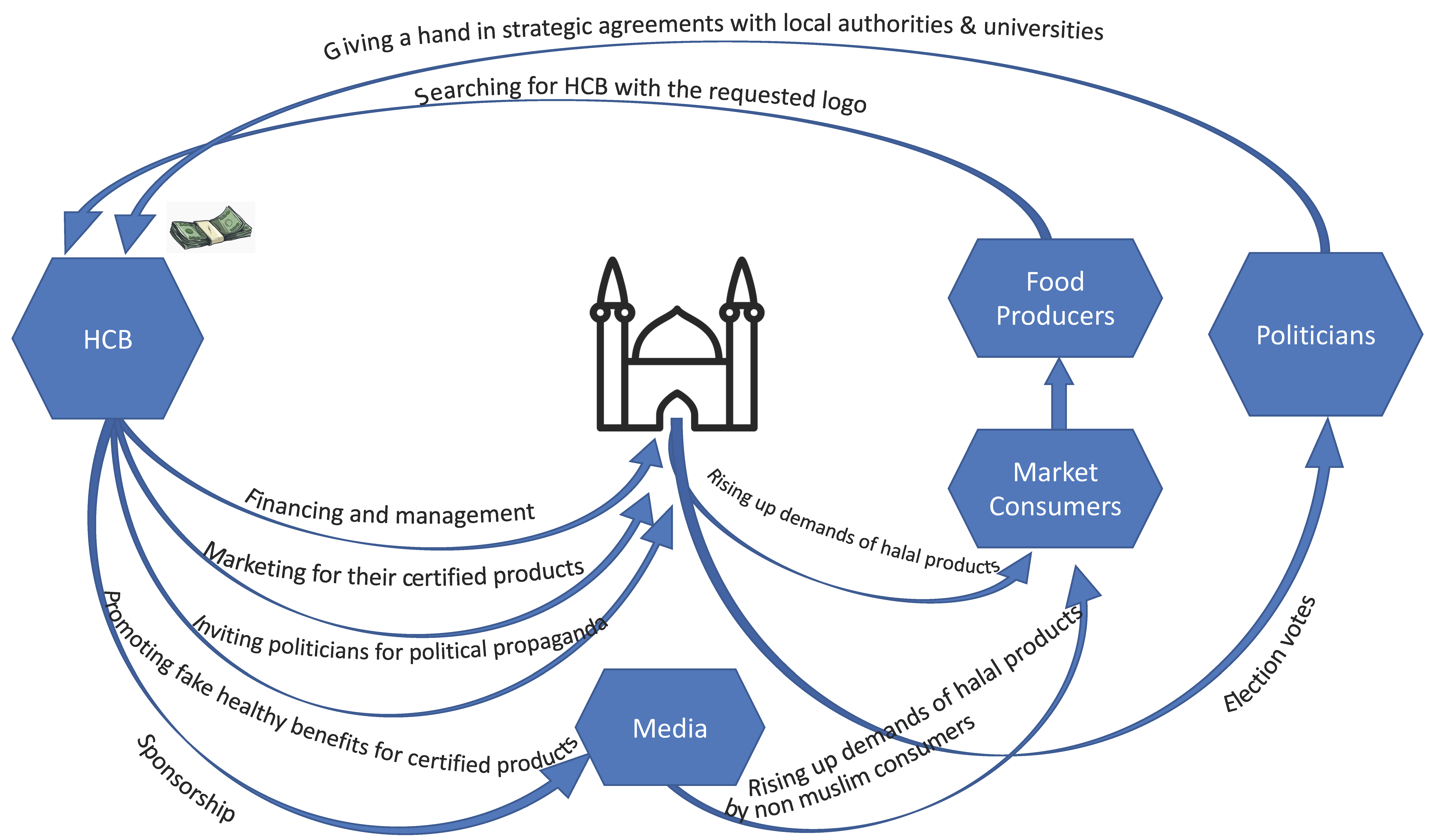

5. The Dark Side of Halal Certification

- (a)

- Many HCBs do not meet governmental halal standards or even the food safety standard ISO 22000 [28] (p. 243–246).

- (b)

- Some HCBs do not have an internal halal system or guidelines for halal requirements [28] (p. 243–246).

- (c)

- Some HCBs do not work according to halal procedures [28] (p. 243–246).

- (d)

- Some HCBs have agreed to follow a set of halal processes or standards, but in practice may often do not follow them [28] (p. 243–246).

- (e)

- Many HCBs do not possess the professional skills of halal requirements; hence, many have been disqualified on religious grounds from carrying out the duties [28] (p. 243–246).

- (f)

- Most HCBs do not disclose information about their procedures in order to avoid criticism from competing HCBs [28] (p. 243–246).

- (g)

- Many HCBs do not employ professional figures with the various competences relevant to food and halal standards (personal communication, Ali Abdallah 2018).

- (h)

- Some HCBs approve meat as halal without an on-site halal audit/supervision of the meat [28] (p. 243–246).

- (i)

- An HAB can demand high fees from an HCB in order to grant halal accreditation, and this can affect the credibility of accredited HCBs, which may need to bribe the halal accreditor to obtain a place in the halal market [28] (p. 243–246).

- (j)

- Sometimes a halal auditor has more than one role inside the HCB, in quality control or on the technical committee, as well as in the certification committee, meaning that the auditor’s impartiality cannot be guaranteed (personal communication, Ali Abdallah 2018).

- (k)

- Members of the certification committee are owners, relatives of owners, or even spouses of HCB members, meaning that their impartiality cannot be guaranteed (personal communication, Ali Abdallah 2018).

- (l)

- Some HCBs manage Islamic associations or mosques, due to a requirement by the international HAB that the HCBs should be committed contributors to Muslim communities in their countries. This is connected to the principle of responsibility and dakwah, i.e., contribution, to mosques, schools, and other forms of Islamic development [37] (p. 6); this encourages those interested in obtaining accreditation to exploit a Muslim community or mosque in their own region.

- (m)

- Halal certifiers in Italy claim that halal certification is above all a religious certification, behaving as if it were the best-made in the world and using marketing and standardising narratives to position themselves as authorities on local foodways [27].

The Halal Market in Italy

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- STATE of the GLOBAL ISLAMIC ECONOMY REPORT 2019/20. 2020. Dinarstandard: COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE. Available online: https://cdn.salaamgateway.com/special-coverage/sgie19-20/full-report.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Ahmed, A. Marketing of halal meat in the United Kingdom. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanios, F.; Ergene, B.A. Halal Food: A History; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nizard, S. Florence Bergeaud-Blackler, Le marché halal ou l’invention d’une tradition. Arch. Sci. Soc. Relig. 2018, 184, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross-Land, L. Consuming Local, Thinking Global: Building a Halal Industry in a World of Made in Italy. Ph.D. Thesis, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA, 15 May 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Rahem, M.A.; Pasqualone, A. The multiplicity of halal standards: A case study of application to slaughterhouses. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, D.; Silvio, F.; Brigitte, M. ISLAM in the EUROPEAN UNION:WHAT’S at STAKE in the FUTURE? Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies European Parliament. 2007. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2007/369031/IPOL-CULT_ET(2007)369031_EN.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- European Council. Council Directive 74/577/EC on Stunning of Animals before Slaughter; L316:10–1; Official journal of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. Council Directive 88/306/EC on Conclusion of the European Convention for the Protection of Animals for Slaughter; L137:25-26; Official journal of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. Council Directive 93/119/EC on the Protection of Animals at the Time of Slaughter or Killing; L340:21–34; Official journal of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. Council Regulation (EC) 1099/2009 of 24 September 2009 on the Protection of Animals at the Time of Killing; L303:1-30; Official journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alwall, J. Muslim Rights and Plights. The Religious Liberty Situation of a Minority in Sweden. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University Press, Lund, Sweden, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, O. The Legal Status of Islamic Minorities in Sweden. In The Legal Treatment of Islamic Minorities in Europe; Aluffi, B.-P.R., Zincone, G., Eds.; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2004; pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Potz, R.; Schinkele, B.; Wolfgang, W. Religionsfreiheit und Tierschutz; Plöchl-Druck (24483): Freistadt, Austria, 2001; pp. 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- Rossella, B. Legal Aspects of Halal Slaughter and Certification in the European Union and and Its Member States. In The Halal Food Hand Book; Al-Teinaz, Y.R., Spear, S., El-Rahim, I.H.A.A., Eds.; Chichester: West Sussex, UK; John Wily & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 225–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rohe, M. Application of shar’a rules in europe—Scope and limits. Welt Islam. 2004, 44, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, M. On the Recognition and Istitutionalisation of Islam in Germany. In Proceedings of the The Response of State Law to the Expression of Cultural Diversity, Brussels, Belgium, 27 September–1 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- General Guidelines for Use of the Term ‘HALAL’. 1997. n.d. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/y2770e/y2770e08.htm#fnB27 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Al Gziri, A. Al-Fiqh Alla Al-Mazaheb Al-Arabaa; Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah: Beirut, Lebanon, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Angelopoulos, T.J. Relationship between added sugars and obesity. J. Obes. Eat. Disord. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-K.; Yong, H.I.; Kim, Y.-B.; Kim, H.-W.; Choi, Y.-S. Edible Insects as a Protein Source: A Review of Public Perception, Processing Technology, and Research Trends. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2019, 39, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Bhatnagar, N.B.; Bhatnagar, R. Bacterial Insecticidal Toxins. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 30, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanamaneichat, C.; Rakkarn, S. Quality Assurance Development of Halal Food Products for Export to Indonesia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 88, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GCC Standardization Organization. Halal Products—Part 2: General Requirements for Halal Certification Bodies; GSO 2055-2/2015(E); GCC Standardization Organization: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LPPOM MUI—Halal MUI Online Certification Service. Majelis Ulama Indonesia, Indonesia. Available online: https://e-lppommui.org/other/about_us.php (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Halal Hub Divison. Procedures for Appointment of Foreign Halal Certification Bodies; Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM): Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2011. Available online: http://www.Halal.gov.my/v4/images/pdf/cb28012014.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Cross-Land Lauren. The Process of Eating Ethically: A Comparison of Religious and National Food Certifications in Italy. In Rethinking Halal; Yakin, A.U., Christians, L.-L., Eds.; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Teinaz, Y.R.; Al-Mazeedi, H.M.M. Halal certification and international Halal standards. In The Halal Food Hand Book; Al-Teinaz, Y.R., Spear, S., El-Rahim, I.H.A.A., Eds.; Chichester: West Sussex, UK; John Wily & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- GCC Accreditation Center. Available online: https://www.gac.org.sa/en/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban, and Diana Beltekian. 2018. Trade and Globalization. Our World in Data. October 2018. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Dug, H. SMIIC and Halal Food Standards Saudi Food and Drug Authority. In Proceedings of the First International Conference and Exhibition on Halal Food Control, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 12–15 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Halal Food Council. Available online: https://www.whfc-halal.com/about-us/history (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- International Halal Accreditation Forum (IHAF). IHAF Establishment—IHAF. Available online: https://www.ihaf.org.ae/en/establishment-of-ihaf/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- List of Recognised Islamic Bodies for Halal Certification of Red Meat—Department of Agriculture. 2020. Available online: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/export/controlled-goods/meat/elmer-3/list-islamic-Halal-certification (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Zlati, M. Mondelēz’s Toblerone Boycotted by European Far-Right Because of Halal Certification. 2018. Available online: https://eu.usatoday.com/story/money/2018/12/24/toblerone-halal-controversy-chocolate-bar-boycotted-far-right/2405914002/ (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Johnson, S. Cory Bernardi Describes Halal Certifiers as Cockroaches Running Scam. Mail Online, 10 April 2018. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5597235/Senator-Cory-Bernardi-describes-Muslim-Halal-certifiers-cockroaches-running-extortion-racket.html (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Latif, M.A. Halal international standards and certification. In The Halal Food Hand Book; Al-Teinaz, Y.R., Spear, S., El-Rahim, I.H.A.A., Eds.; Chichester: West Sussex, UK; John Wily & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Merlino, R. Sicilian Mafia, Patron Saints, and Religious Processions: The Consistent Face of an Ever-Changing Criminal Organization. Calif. Ital. Stud. 2014, 5. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sz659dn (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Ariffin, M.F.M.; Riza, N.S.M.; Hamid, M.F.A.; Awae, F.; Nasir, B.M. Halal Food Crime in Malaysia: An Analysis On Illegal Meat Cartel Issues. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 1407–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H. Halal Meat Scandal: Malaysian Authorities Slammed for Perceived Inaction. The Straits Times. 2 January 2021. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/halal-meat-scandal-malaysian-authorities-slammed-for-perceived-inaction (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Galici, F. “Finiti in Ospedale”. L’imam di Bari Aggredisce la Troupe di Striscia. 2021. Available online: https://www.ilgiornale.it/news/cronache/insultata-e-aggredita-finisce-male-linviata-striscia-notizia-1981382.html (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Longo, G. Arrestato Imam Lorenzini “Spariti” Soldi Da Conto Sequestrato. Lagazzetta Del Mezzogiorno. 2018. Available online: https://www.lagazzettadelmezzogiorno.it/news/home/978880/bari-arrestato-imam-lorenzini-spariti-soldi-da-conto-sequestrato.html (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Accredia. Firma del Protocollo d’Intesa ACCREDIA ESMA per la Certificazione Halal. 2015. Available online: https://www.accredia.it/pubblicazione/20-10-2015-firma-del-protocollo-d%C2%92intesa-accredia-esma-per-la-certificazione-Halal/ (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Accredia. Al Via le Certificazioni dei Prodotti Halal. 2016. Available online: https://www.accredia.it/2016/03/25/25-03-2016-al-via-le-certificazioni-dei-prodotti-Halal/ (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- ESMA. (n.d.) List of Halal Certification Bodies with ESMA. Available online: http://Halal.ae/OpenData/HalalCertificationBodieswithESMA (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- .Goga, B.C. Halal Food in Italy. In The Halal Food Hand Book; Al-Teinaz, Y.R., Spear, S., El-Rahim, I.H.A.A., Eds.; Chichester: West Sussex, UK; John Wily & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 413–435. [Google Scholar]

- Giammaria, A. L’alimentazione Halal, Tra Religione E Benessere: Dibattito a Casamassima. Borderline24. 2016. Available online: https://www.borderline24.com/2016/11/24/lalimentazione-halal-religione-benessere-dibattito-casamassima/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Parstoday. Consumare Cibo Halal Fa Bene Alla Salute. 2016. Available online: https://parstoday.com/it/news/italia-i60559-consumare_cibo_halal_fa_bene_alla_salute (accessed on 15 April 2021).

| Protection of Animals at the Time of Slaughter in Islam from 610 CE | Protection of Animals at the Time of Slaughter in Directive 93/119/EC |

|---|---|

| 1. An animal must not be slaughtered in front of another animal [19]. | 1. Animals must be unloaded as soon as possible after arrival. If delay is unavoidable they must be protected from extremes of weather and provided with adequate ventilation. |

| 2. The knife must not be sharpened in front of the animal to be slaughtered [19]. | 2. Animals must be protected from adverse weather conditions. If they have been subjected to high temperatures in humid weather they must be cooled by appropriate means. |

| 3. When animals have travelled long distances, they shall be given a rest before slaughtering [19]. | 3. For animals that have been stunned, blood-letting must be started as soon as possible after stunning and be carried out in such a way as to bring about rapid, profuse, and complete blood-letting. In any event, the blood-letting must be carried out before the animal regains consciousness. |

| 4. Slaughtering shall be done by the right hand and cutting shall be done quickly [19]. | 4. Animals must be restrained in an appropriate manner in such a way as to spare them any avoidable pain, suffering, agitation, injury, or contusions. |

| 5. It is prohibited to disfigure animals [19]. | 5. Animals’ legs must not be tied, and animals must not be suspended before stunning or killing. However, poultry and rabbits may be suspended for slaughter provided that appropriate measures are taken to ensure that, on the point of being stunned, they are in a sufficiently relaxed state for stunning to be carried out effectively and without undue delay. |

| 6. Provide drinking water to animals before slaughtering [19]. | 6. Animals that are not taken directly upon arrival to the place of slaughter must have drinking water available to them from appropriate facilities at all times. |

| 7. The slaughtered animal shall be treated mercifully. It must not be tortured or slaughtered improperly and the slaughtering tool must not be moved in many directions [19]. | 7. Animals that are kept for 12 h or more at a slaughterhouse must be lairaged and, where appropriate, tethered in such a way that they can lie down without difficulty. Where animals are not tethered, food must be provided in a way that will permit the animals to feed undisturbed. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdallah, A. Has the Lack of a Unified Halal Standard Led to a Rise in Organised Crime in the Halal Certification Sector? Forensic Sci. 2021, 1, 181-193. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci1030016

Abdallah A. Has the Lack of a Unified Halal Standard Led to a Rise in Organised Crime in the Halal Certification Sector? Forensic Sciences. 2021; 1(3):181-193. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci1030016

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdallah, Ali. 2021. "Has the Lack of a Unified Halal Standard Led to a Rise in Organised Crime in the Halal Certification Sector?" Forensic Sciences 1, no. 3: 181-193. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci1030016

APA StyleAbdallah, A. (2021). Has the Lack of a Unified Halal Standard Led to a Rise in Organised Crime in the Halal Certification Sector? Forensic Sciences, 1(3), 181-193. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci1030016