Genetic Differentiation and Population Structure of the Freshwater Snail Rivomarginella morrisoni (Gastropoda: Marginellidae) in Central and Southern Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Identification and Morphological Study

2.2. DNA Isolation

2.3. Sequence-Related Amplified Polymorphism (SRAP) Analysis

2.4. Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) Analysis

2.5. Data Scoring and Molecular Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Analysis

3.2. Polymorphism Disclosed by SRAP and ISSR Primers

3.3. Genetic Distance and Population Structure Analyses

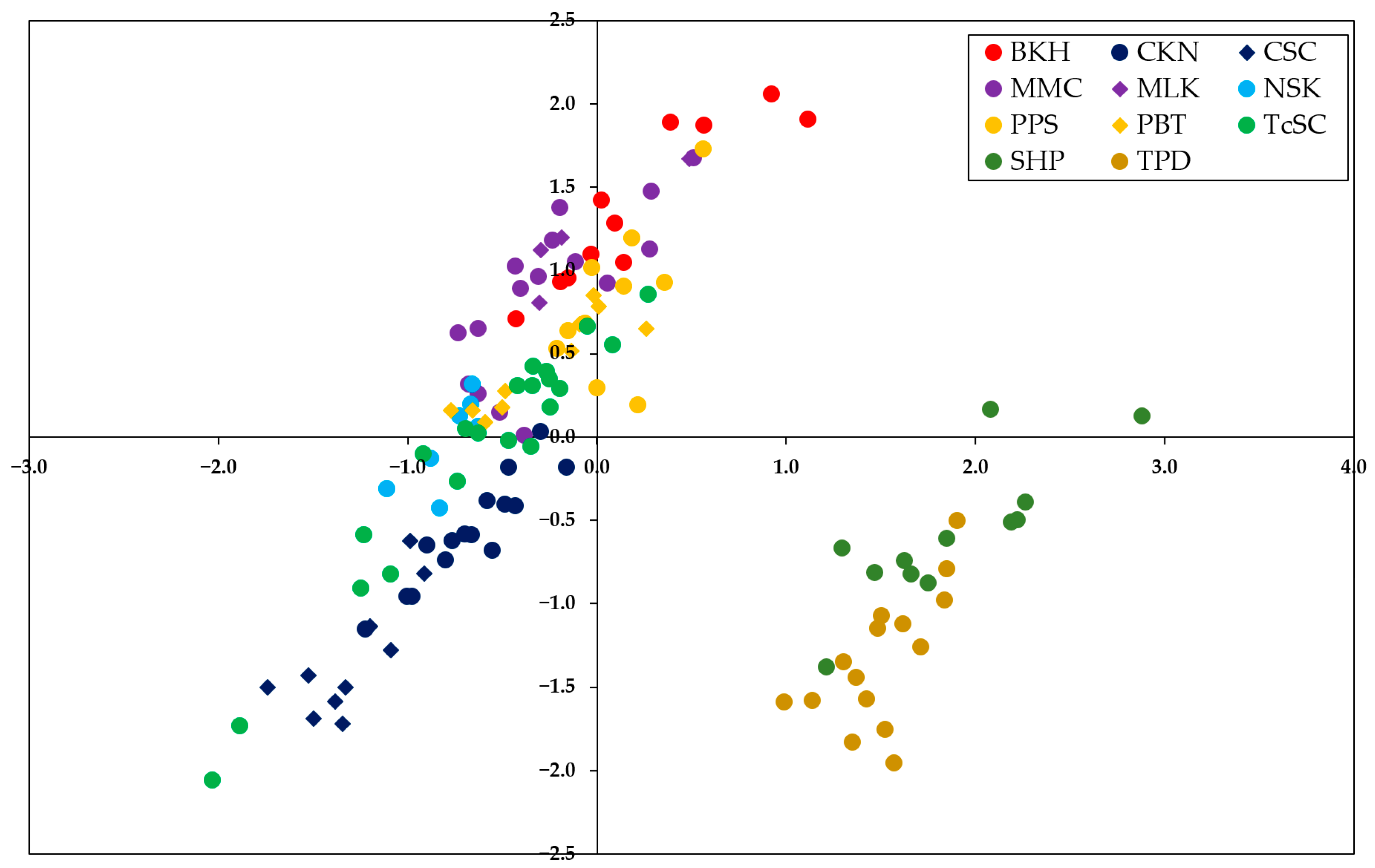

3.3.1. Based on SRAP Markers

3.3.2. Based on ISSR Markers

3.3.3. Based on Combined SRAP and ISSR Markers

3.4. Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA)

3.5. Pairwise Genetic Differentiation

3.5.1. Based on SRAP Markers

3.5.2. Based on ISSR Markers

3.5.3. Based on Combined SRAP and ISSR Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Covich, A.P.; Palmer, M.A.; Crowl, T.A. The Role of Benthic Invertebrate Species in Freshwater Ecosystems: Zoobenthic species influence energy flows and nutrient cycling. BioScience 1999, 49, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.R.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Bowerman, J.; Li, J. Biogeography of the Freshwater Gastropod, Planorbella trivolvis, in the Western United States. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, E.E.; Gargominy, O.; Ponder, W.F.; Bouchet, P. Global Diversity of Gastropods (Gastropoda; Mollusca) in Freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.D.; Bogan, A.E.; Brown, K.M.; Burkhead, N.M.; Cordeiro, J.R.; Garner, J.T.; Hartfield, P.D.; Lepitzki, D.A.W.; Mackie, G.L.; Pip, E.; et al. Conservation Status of Freshwater Gastropods of Canada and the United States. Fisheries 2013, 38, 247–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, G.; Dong, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, P. Analysis of Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Bellamya quadrata from Lakes of Middle and Lower Yangtze River. Genetica 2015, 143, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomans, E.H.; Clover, W.P. The Genus Rivomarginella (Gastropoda, Marginellidae). Beaufortia 1972, 20, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, R.A.M. Description of New Non-Marine Mollusks from Asia; Archiv für Molluskenkunde: Frankfurt, Germany, 1968; pp. 275–277. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, R.A.M. The Non-Marine Aquatic Mollusca of Thailand; Archiv für Molluskenkunde: Frankfurt, Germany, 1974; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- Rivomarginella morrisoni The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T184928A1766366.en (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Subpayakom, N.; Dumrongrojwattana, P.; Poeaim, S. Chemosensory-Driven Foraging and Nocturnal Activity in the Freshwater Snail Rivomarginella morrisoni (Gastropoda, Marginellidae): A Laboratory-Based Study. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2025, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Quiros, C.F. Sequence-Related Amplified Polymorphism (SRAP), a New Marker System Based on a Simple PCR Reaction: Its Application to Mapping and Gene Tagging in Brassica. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 103, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietkiewicz, E.; Rafalski, A.; Labuda, D. Genome Fingerprinting by Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR)-Anchored Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification. Genomics 1994, 20, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zheng, J.; Nie, H.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Meretrix petechialis in China Revealed by Sequence-related Amplified Polymorphism Markers. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etukudo, O.; Asuquo, B.; Ekaluo, U.; Okon, B.; Ekerette, E.; Umoyen, A.; Udensi, O.; Ibom, L.; Afiukwa, C.; Igwe, D. Evaluation of Genetic Diversity in Giant African Land Snails Using Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR) Markers. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Shentu, X.; Pan, Y.; Bai, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, H. Evaluation of Genetic Diversity in the Golden Apple Snail, Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck), from Different Geographical Populations in China by Inter Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, F.J. NTSYSpc: Numerical Taxonomy System, Version 2.11X; Exeter Software: Setauket, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. Available online: http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin Suite Ver 3.5: A New Series of Programs to Perform Population Genetics Analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falush, D.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, J.K. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data: Linked Loci and Correlated Allele Frequencies. Genetics 2003, 164, 1567–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the Number of Clusters of Individuals Using the Software STRUCTURE: A Simulation Study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.X. StructureSelector: A Web-Based Software to Select and Visualize the Optimal Number of Clusters Using Multiple Methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hanlon, A.; Feeney, K.; Dockery, P.; Gormally, M.J. Quantifying Phenotype-environment Matching in the Protected Kerry Spotted Slug (Mollusca: Gastropoda) using Digital Photography: Exposure to UV Radiation Determines Cryptic Colour Morphs. Front. Zool. 2017, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford, D.; Lohman, D.J.; Sodhi, N.S.; Ng, P.K.L.; Meier, R.; Winker, K.; Ingram, K.K.; Das, I. Cryptic Species as a Window on Diversity and Conservation. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padial, J.M.; Miralles, A.; De la Riva, I.; Vences, M. The Integrative Future of Taxonomy. Front. Zool. 2010, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, B.A.; Al-Doss, A.A.; Assaeed, A.M.; Javed, M.M.; Ghazy, A.I.; Al-Rowaily, S.L.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M. Genetic Variation among Aeluropus lagopoides Populations Growing in Different Saline Regions. Diversity 2024, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancı, F.; Paşazade, E. A Comparison of Efficiency Parameters of SRAP and ISSR Markers in Revealing Variation in Allium Germplasm. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, C.M.; Johnston, I.A. Genomic Tools and Selective Breeding in Molluscs. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 334494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybom, H. Comparison of Different Nuclear DNA Markers for Estimating Intraspecific Genetic Diversity in Plants. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations, Volume 4: Variability Within and Among Natural Populations; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tian-Bi, Y.N.; Jarne, P.; Konan, J.N.K.; Utzinger, J.; N’Goran, E.K. Contrasting the Distribution of Phenotypic and Molecular Variation in the Freshwater Snail Biomphalaria pfeifferi, the Intermediate Host of Schistosoma mansoni. Heredity 2013, 110, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, X.; Zhan, Z.; Feng, J.; Xie, T.; Li, Y. Development of Microsatellite Markers and Evaluation of the Genetic Diversity of the Edible Sea Anemone Paracondylactis sinensis (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) in China. Biodivers. Data J. 2024, 12, e134363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, W.C.; McKay, J.K.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Allendorf, F.W. Harnessing Genomics for Delineating Conservation Units. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidyananda, N.; Jamir, I.; Nowakowska, K.; Varte, V.; Vendrame, W.A.; Devi, R.S.; Nongdam, P. Plant Genetic Diversity Studies: Insights from DNA Marker Analyses. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 607–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Schmidt, D.J.; Finn, D.S. Genes in Streams: Using DNA to Understand the Movement of Freshwater Fauna and Their Riverine Habitat. BioScience 2009, 59, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, C. Defining ‘Evolutionarily Significant Units’ for Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1994, 9, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedosov, A.E.; Caballer Gutierrez, M.; Buge, B.; Sorokin, P.V.; Puillandre, N.; Bouchet, P. Mapping the Missing Branch on the Neogastropod Tree of Life: Molecular Phylogeny of Marginelliform Gastropods. J. Molluscan Stud. 2019, 85, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Dong, X.; Xu, K.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. The Characterization of the Mitochondrial Genome of Fulgoraria rupestris and Phylogenetic Considerations within the Neogastropoda. Genes 2024, 15, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| River Basins | Sampling Sites | Provinces | Sample Codes | GPS Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Region | ||||

| Bang Pakong | Khwae Hanuman | Prachin Buri | BKH | 13°59′33.7″ N 101°42′50.5″ E |

| Chao Phraya | Khlong Noi | Chai Nat | CKN | 15°01′28.4″ N 100°12′44.4″ E |

| Sanam Chai Temple | Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya | CSC | 14°12′07.7″ N 100°30′29.4″ E | |

| Mae Klong | Manee Chot | Ratchaburi | MMC | 13°40′10.3″ N 99°49′00.5″ E |

| Luk Kae Beach | Kanchanaburi | MLK | 13°52′04.6″ N 99°49′01.6″ E | |

| Nan | Sairong Khon Temple | Phichit | NSK | 16°10′39.0″ N 100°24′08.0″ E |

| Pa Sak | Pa Sak River | Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya | PPS | 14°27′34.9″ N 100°35′58.5″ E |

| Ban Ta Luang | Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya | PBT | 14°32′08.5″ N 100°45′01.8″ E | |

| Tha Chin | Sam Chuk | Suphan Buri | TcSC | 14°46′23.9″ N 100°05′19.8″ E |

| Southern Region | ||||

| Songkhla Lake | Had Phat Thong | Phatthalung | SHP | 7°30′28.0″ N 100°11′32.2″ E |

| Tapi | Phum Duang | Surat Thani | TPD | 9°05′52.4″ N 99°12′22.3″ E |

| Primer Name | Forward (5′–3′) | Primer Name | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Me1 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGATA | Em1 | GACTGCGTACGAATTAAT |

| Me2 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | Em2 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTGC |

| Me3 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAT | Em3 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGAC |

| Me4 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGACC | Em4 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| Me5 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAG | Em5 | GACTGCGTACGAATTAAC |

| Em6 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGCA |

| Primer Name | Sequences (5′–3′) | Annealing Temp. |

|---|---|---|

| UBC807 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGT | 48 °C |

| UBC808 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGC | 50 °C |

| UBC809 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGG | 50 °C |

| UBC834 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGYT | 50 °C |

| UBC835 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGYC | 52 °C |

| UBC866 | CTCCTCCTCCTCCTCCTC | 58 °C |

| Populations | Shell Length (mm) | Shell Width (mm) | Spire Length (mm) | Spot Pattern * | Spot Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BKH | 8.76 ± 0.67 | 5.78 ± 0.38 | 1.22 ± 0.24 | Type 1 | Black |

| CKN | 6.89 ± 0.41 | 4.35 ± 0.28 | 1.40 ± 0.13 | Type 1 | Black |

| CSC | 5.99 ± 0.43 | 3.70 ± 0.26 | 1.19 ± 0.15 | Type 1 | Black |

| MMC | 8.11 ± 0.56 | 5.33 ± 0.38 | 1.03 ± 0.23 | Type 1 | Black |

| MLK | 8.61 ± 0.30 | 5.57 ± 0.25 | 1.08 ± 0.21 | Type 1 | Black |

| NSK | 7.31 ± 0.26 | 4.57 ± 0.25 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | Type 1 | Black |

| PPS | 8.28 ± 0.46 | 5.41 ± 0.27 | 1.41 ± 0.20 | Type 1 | Black |

| PBT | 7.81 ± 0.42 | 5.05 ± 0.26 | 1.22 ± 0.19 | Type 1 | Black |

| TcSC | 7.36 ± 0.92 | 4.56 ± 0.57 | 1.19 ± 0.21 | Type 1 | Black |

| SHP | 8.15 ± 0.38 | 5.19 ± 0.32 | 1.50 ± 0.20 | Type 2 | Black plus brown |

| TPD | 9.06 ± 0.66 | 5.67 ± 0.28 | 1.41 ± 0.26 | Type 2 | Black plus brown |

| Markers | Primers | Amplified Bands | Polymorphic Bands | % Polymorphism | PIC * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRAP | ME1/EM2 | 8 | 7 | 87.50 | 0.58 |

| ME1/EM3 | 13 | 10 | 76.92 | 0.55 | |

| ME2/EM1 | 5 | 1 | 20.00 | 0.05 | |

| ME2/EM4 | 8 | 6 | 75.00 | 0.56 | |

| ME3/EM1 | 9 | 5 | 55.56 | 0.31 | |

| ME3/EM2 | 11 | 5 | 45.45 | 0.21 | |

| ME3/EM3 | 6 | 3 | 50.00 | 0.20 | |

| ME3/EM5 | 7 | 6 | 85.71 | 0.34 | |

| Total | 67 | 43 | 2.80 | ||

| Average | 8.38 | 5.38 | 62.02 | 0.35 | |

| ISSR | UBC807 | 6 | 4 | 66.67 | 0.42 |

| UBC808 | 5 | 2 | 40.00 | 0.29 | |

| UBC809 | 3 | 2 | 66.67 | 0.23 | |

| UBC834 | 9 | 7 | 77.78 | 0.35 | |

| UBC835 | 8 | 2 | 25.00 | 0.07 | |

| UBC866 | 5 | 3 | 60.00 | 0.25 | |

| Total | 36 | 20 | 1.61 | ||

| Average | 6.00 | 3.33 | 56.02 | 0.27 |

| Source of Variation | df | Sum of Squares | Variance Components | Percentage of Variation | PhiPT | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For SRAP | ||||||

| Among populations | 10 | 224.467 | 5.136 | 77.76 | ||

| Within populations | 34 | 49.933 | 1.469 | 22.24 | ||

| Total | 44 | 274.400 | 6.605 | 100 | 0.778 | <0.001 |

| For ISSR | ||||||

| Among populations | 10 | 130.028 | 3.051 | 84.92 | ||

| Within populations | 34 | 18.417 | 0.542 | 15.08 | ||

| Total | 44 | 148.444 | 3.593 | 100 | 0.849 | <0.001 |

| For combined SRAP and ISSR markers | ||||||

| Among populations | 10 | 354.494 | 8.187 | 80.29 | ||

| Within populations | 34 | 68.350 | 2.010 | 19.71 | ||

| Total | 44 | 422.844 | 10.197 | 100 | 0.803 | <0.001 |

| Populations | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BKH | CKN | CSC | MMC | MLK | NSK | PPS | PBT | TcSC | SHP | TPD | |

| For SRAP | |||||||||||

| BKH | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| CKN | 0.675 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| CSC | 0.804 | 0.522 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| MMC | 0.645 | 0.587 | 0.711 | 0.000 | |||||||

| MLK | 0.694 | 0.630 | 0.758 | 0.028 | 0.000 | ||||||

| NSK | 0.697 | 0.575 | 0.768 | 0.685 | 0.729 | 0.000 | |||||

| PPS | 0.703 | 0.464 | 0.475 | 0.688 | 0.700 | 0.720 | 0.000 | ||||

| PBT | 0.770 | 0.575 | 0.527 | 0.733 | 0.734 | 0.776 | 0.200 | 0.000 | |||

| TcSC | 0.879 | 0.833 | 0.933 | 0.686 | 0.788 | 0.936 | 0.904 | 0.927 | 0.000 | ||

| SHP | 0.842 | 0.837 | 0.881 | 0.845 | 0.847 | 0.900 | 0.825 | 0.855 | 0.931 | 0.000 | |

| TPD | 0.680 | 0.754 | 0.838 | 0.734 | 0.750 | 0.813 | 0.794 | 0.815 | 0.931 | 0.802 | 0.000 |

| For ISSR | |||||||||||

| BKH | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| CKN | 0.851 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| CSC | 0.889 | 0.778 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| MMC | 0.802 | 0.762 | 0.869 | 0.000 | |||||||

| MLK | 0.811 | 0.821 | 0.886 | 0.556 | 0.000 | ||||||

| NSK | 0.703 | 0.619 | 0.736 | 0.715 | 0.623 | 0.000 | |||||

| PPS | 0.876 | 0.795 | 0.583 | 0.856 | 0.873 | 0.748 | 0.000 | ||||

| PBT | 0.853 | 0.833 | 0.667 | 0.851 | 0.862 | 0.618 | 0.697 | 0.000 | |||

| TcSC | 0.839 | 0.869 | 0.807 | 0.884 | 0.894 | 0.833 | 0.745 | 0.841 | 0.000 | ||

| SHP | 0.901 | 0.921 | 0.926 | 0.869 | 0.915 | 0.856 | 0.921 | 0.917 | 0.908 | 0.000 | |

| TPD | 0.871 | 0.876 | 0.907 | 0.856 | 0.887 | 0.844 | 0.880 | 0.888 | 0.873 | 0.876 | 0.000 |

| For combined SRAP and ISSR markers | |||||||||||

| BKH | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| CKN | 0.748 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| CSC | 0.841 | 0.623 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| MMC | 0.703 | 0.642 | 0.775 | 0.000 | |||||||

| MLK | 0.728 | 0.685 | 0.799 | 0.197 | 0.000 | ||||||

| NSK | 0.700 | 0.575 | 0.754 | 0.698 | 0.701 | 0.000 | |||||

| PPS | 0.787 | 0.607 | 0.510 | 0.761 | 0.761 | 0.732 | 0.000 | ||||

| PBT | 0.801 | 0.680 | 0.574 | 0.773 | 0.769 | 0.728 | 0.433 | 0.000 | |||

| TcSC | 0.863 | 0.848 | 0.896 | 0.798 | 0.838 | 0.890 | 0.868 | 0.902 | 0.000 | ||

| SHP | 0.861 | 0.864 | 0.895 | 0.850 | 0.862 | 0.888 | 0.861 | 0.873 | 0.924 | 0.000 | |

| TPD | 0.768 | 0.798 | 0.863 | 0.776 | 0.797 | 0.825 | 0.824 | 0.840 | 0.855 | 0.824 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Subpayakom, N.; Wanitjirattikal, P.; Dumrongrojwattana, P.; Poeaim, S. Genetic Differentiation and Population Structure of the Freshwater Snail Rivomarginella morrisoni (Gastropoda: Marginellidae) in Central and Southern Thailand. Taxonomy 2026, 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010007

Subpayakom N, Wanitjirattikal P, Dumrongrojwattana P, Poeaim S. Genetic Differentiation and Population Structure of the Freshwater Snail Rivomarginella morrisoni (Gastropoda: Marginellidae) in Central and Southern Thailand. Taxonomy. 2026; 6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSubpayakom, Navapong, Puntipa Wanitjirattikal, Pongrat Dumrongrojwattana, and Supattra Poeaim. 2026. "Genetic Differentiation and Population Structure of the Freshwater Snail Rivomarginella morrisoni (Gastropoda: Marginellidae) in Central and Southern Thailand" Taxonomy 6, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010007

APA StyleSubpayakom, N., Wanitjirattikal, P., Dumrongrojwattana, P., & Poeaim, S. (2026). Genetic Differentiation and Population Structure of the Freshwater Snail Rivomarginella morrisoni (Gastropoda: Marginellidae) in Central and Southern Thailand. Taxonomy, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010007