Adapting Voice Assistant Technology for Older Adults: A Comprehensive Study on Usability, Learning Patterns, and Acceptance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ 1:

- To what extent can older adults 55+ learn to operate VCDs autonomously or with external support, and how do they evaluate their ease of use?

- RQ 2:

- What patterns and intensities of VCDs use are evident among older adults 55+? Which application areas are used, and how are the devices integrated into everyday life?

- RQ 3:

- How does the discrepancy between initial perceptions and reservations about VCDs and actual usage experiences evolve among older adults 55+?

- RQ 4:

- What specific problems and shortcomings in VCDs functionality do older adults 55+ identify, and how do these relate to objectively identifiable issues?

2. Related Work

2.1. Usability and Acceptance of VCDs Among Older Adults

2.2. Barriers to Use and Privacy Concerns

2.3. Contribution of This Study

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Participants—Older Adults 55+, Selection, Recruitment, Role of CHs, and Ethics

- Age group “Pre-Retirement (55–64 years)”: This age group includes people close to the official retirement age. Many of them are still actively working, while others have already retired. Statistics show that employment is already declining significantly in this age segment. However, this group—also known as “baby boomers” [36]—makes up a significant proportion (15%) [37] of the total population of the Federal Republic of Germany. This group is essential because they have directly experienced the incipient digital transformation [38,39].

- Age group “Senior citizens (65–74 years)” is the age group of traditional pensioners. This age group already has fewer contact points with digital technologies [39].

- Age group “Ancient (75 years and older)” includes people who have already reached an advanced age. They can have different health challenges and are often dependent on support. Digital technologies have not played a role for this group of people for most of their lives [39].

3.1.1. Participant Selection

3.1.2. Participant Recruitment

3.1.3. Participants—The Role of CHs

3.1.4. Ethics

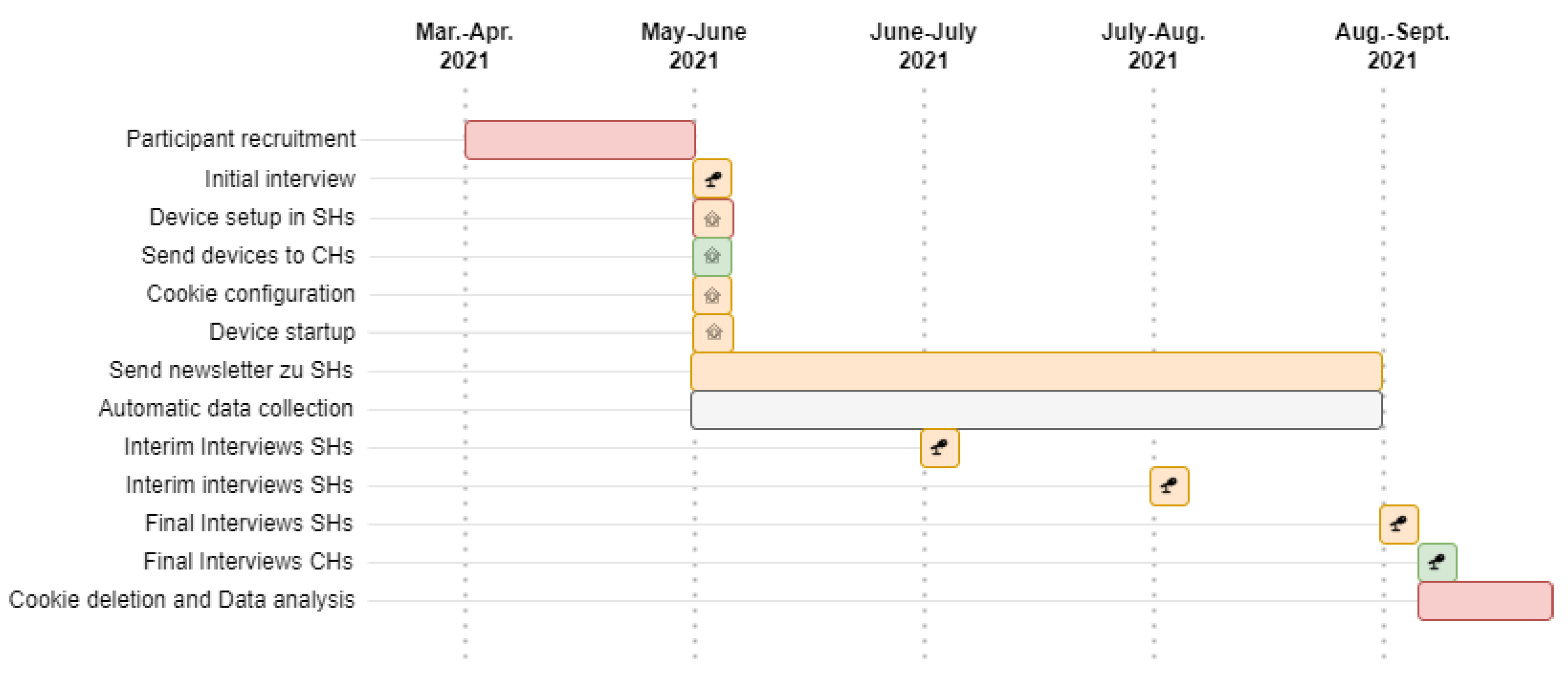

3.2. Methodological Procedure

3.2.1. Selection of a Suitable VCD

3.2.2. Research Method

- Semi-structured personal guided interviews conducted at four-, eight-, and twelve-week intervals, combined with usage logs from the Amazon API in the SHs.

- Semi-structured telephone interviews with CHs after thirteen weeks.

- Analysis of all voice commands and responses recorded by the VCD using session cookies in usage logs.

3.3. Procedure

3.3.1. Initial Interview and Device Setup

3.3.2. Interim Interviews (After Four and Eight Weeks of Use)

3.3.3. Final Interviews with SHs (After Twelve Weeks of Use)

3.3.4. Telephone Interviews with CHs (After 13 Weeks of Use)

3.3.5. Usage Logs

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Autonomous Learnability and Evaluation of Usability

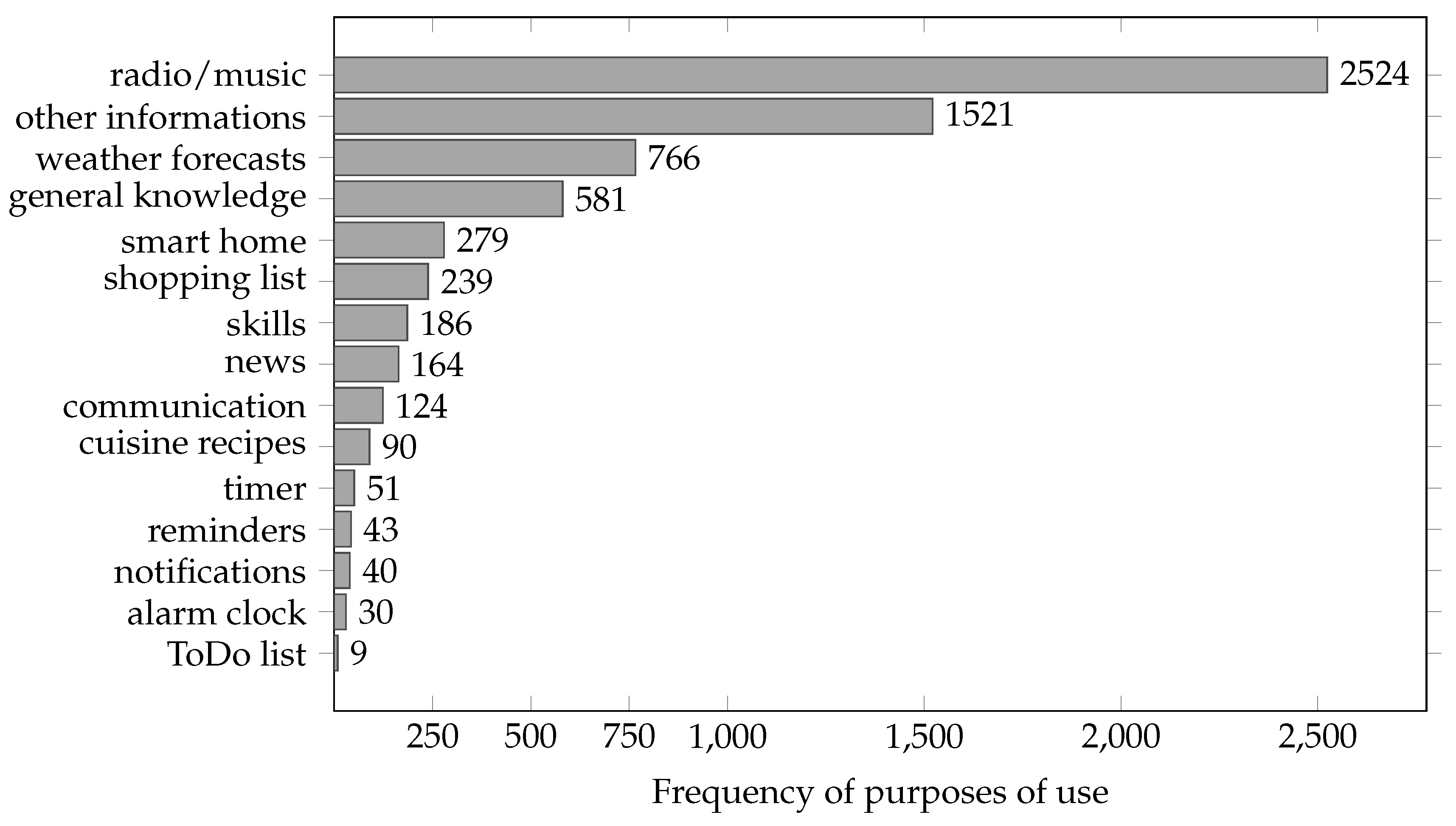

4.2. Purposes and Intensity of Use

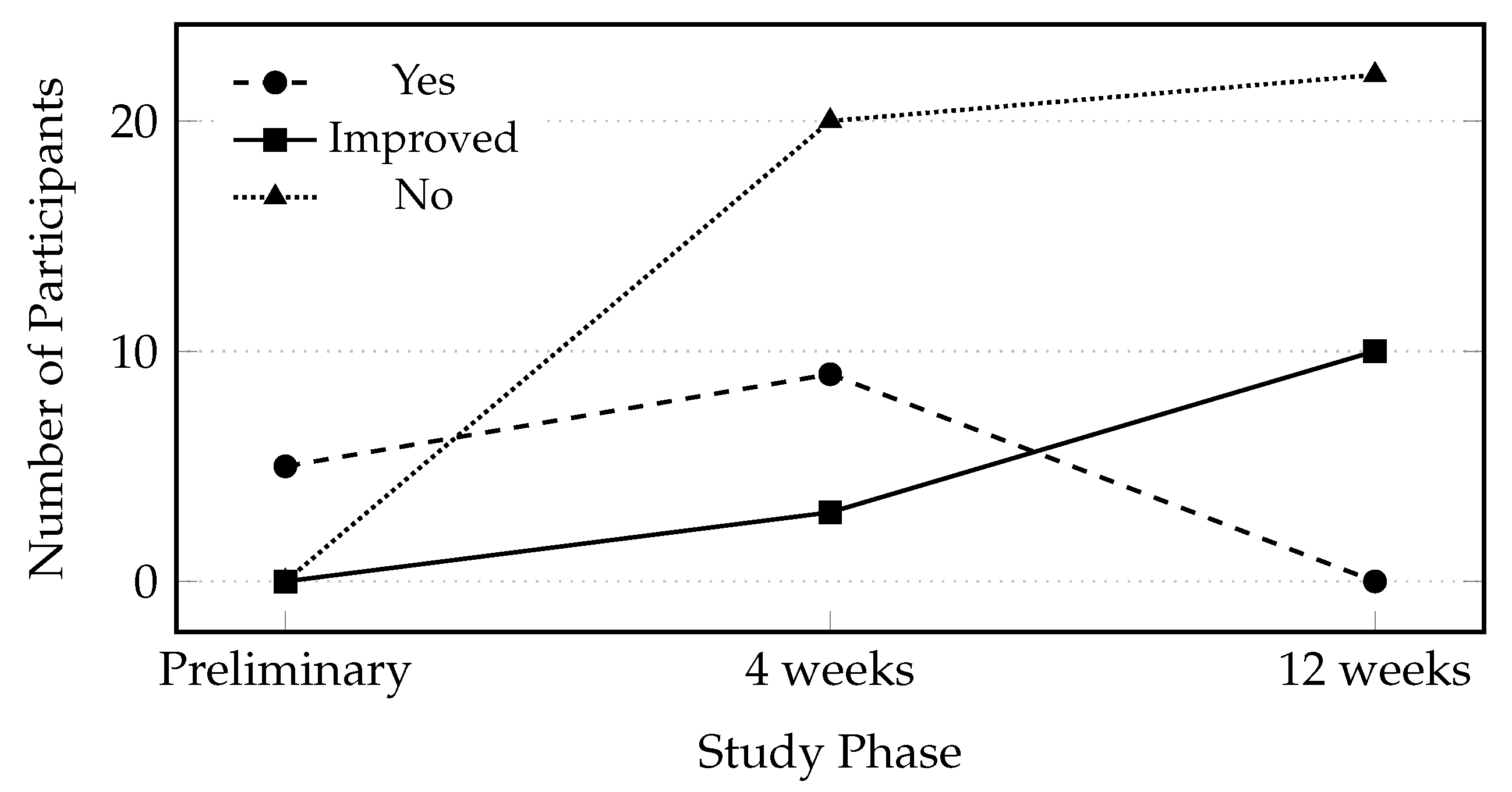

4.3. Discrepancy Between Initial Perceptions and Actual Usage

4.4. Reservations and Barriers Hindering Usage

4.5. Problems and Functional Deficits in the Use of VCD

4.6. Distinguishing Perceived Problems and Functional Deficits from Actual Issues

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Related Work

5.2. New Insights and Contributions

5.3. Research Gaps and Implications

5.4. Limitations

5.5. Conclusion and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CH | Complementary household |

| DIT | Deggendorf Institute of Technology |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| RQ | Research questions |

| SH | Household of older adults |

| VA | Voice assistant |

| VCD | Voice-controlled device |

Appendix A

| Category: Technology Affinity | |

|---|---|

| Guiding question: | What do you think of digital technology in general, such as smartphones, tablets, or PCs? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | What negative/positive experiences did you have with it? Why? |

| Contents | Questions |

| Attitude toward digital technologies | Which device(s) do you own? |

| What do you like about the device(s)? | |

| Why are you not familiar with it? | |

| Have you tried the device before? | |

| Have there been any problems? | |

| Do you have any concerns/reservations? | |

| Ownership of equipment | What devices do you own? |

| Did you buy the device? | |

| Use of the devices | For what purposes do you use the device? |

| Ability to use | Do you know how to operate the device? |

| Origin of knowledge in handling | Did you learn how to operate them yourself? |

| Have you or did you already use digital devices during your professional career? | |

| Support needs | Who can help you with any problems? |

| Category: Voice Assistants/Alexa | |

|---|---|

| Guiding question: | Have you ever heard of “Alexa”? What is your attitude towards it? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | Have you ever had any experience with it? Why? |

| Contents | Questions |

| Attitude to “Alexa” | Do you know “Alexa”? |

| What have you heard about it? | |

| Functionality of “Alexa” | Do you know what you can use “Alexa”? |

| Do you think “Alexa” could be fun for them? | |

| Interest in the technology | Would you like to try “Alexa”? |

| What prevents you from trying “Alexa”? | |

| Suppose you were given “Alexa” as a gift. Would you still not want to try “Alexa”? |

| Category: Living Conditions/Daily Life | |

|---|---|

| Guiding question: | Please tell us something about yourself: How do you live? Are you still working? How is your everyday life? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | Is there anything else? And further? What happened next? And what else? |

| Contents | Questions |

| Family status | Do you live alone or in a cohabitation? |

| Are there any family members living in your house/apartment? | |

| Do you have children? | |

| What is your children’s profession? | |

| Do you have grandchildren? | |

| Professional practice | Are you still employed? |

| What is your profession? | |

| When did you retire? | |

| Do you still have a marginal job? | |

| Mobility | Do you own a car? |

| How do you do your shopping or get to the doctor? | |

| Living Situation/Daily Life | What does your daily routine look like? |

| Does anything change on the weekends? | |

| Are your everyday tasks shared with your life partner? | |

| Do you do things together with your life partner? | |

| Do you prepare your meals? | |

| Who helps you with this? | |

| Do you depend on external help, e.g., cleaning help, relatives? | |

| Do you sometimes feel bored or perhaps lonely? | |

| Hobbies | What hobbies do you practice? |

| Guiding question: | What do you think of “Alexa”, and how do you get along with “Her”? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | Why do you have this impression? What problems of a technical nature have occurred? |

| Are there any other problems? Is the operation of “Alexa” simple? | |

| Contents | Questions |

| Device operation | Do you know the meaning of the different colored light strips (orange)? |

| Do you know how to retrieve and delete received messages? | |

| Do you know how to recognize that there is an Internet connection? | |

| Do “Alexa” understand you? | |

| How did you react to it? | |

| Usability | What do you like about “Alexa” and what don’t you like? |

| Have you been angry about “Alexa” or perhaps particularly pleased? | |

| Is “Alexa” polite to you? | |

| What do you think of the rotating display? | |

| Does anything about “Alexa” bother you? | |

| Has “Alexa” responded without being addressed by you? | |

| Usage/non-usage | Why have you not yet used/tried “Alexa”? |

| Do you know how to use “Alexa”? | |

| Would it be helpful if we explained “Alexa” to you again? | |

| Features | Do you like the possible applications of “Alexa”? |

| Do you know what else “Alexa” can do? | |

| Can you think of anything you want to do with “Alexa”? | |

| Is the newsletter helpful? | |

| Have you tried out the tips? | |

| Have you told friends or acquaintances that you have an “Alexa”? | |

| Have you talked to friends or acquaintances about “Alexa”? | |

| Reservations | Do you have any reservations about using “Alexa”? |

| Have you also unplugged “Alexa” once? | |

| Have you muted the microphone? | |

| Do you feel you are being monitored by “Alexa”? | |

| Has the camera been switched off by you? |

| Guiding question: | Has anything changed regarding how you deal with “Alexa” since our last visit? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | Can you think of anything else to say about this? What else? |

| Is there anything else you can tell us? | |

| Contents | Questions |

| Device operation | What did you do as a result? |

| Are there still problems with “Alexa”? | |

| Can we help you? | |

| Usage / non-usage | Did you notice something in the use of “Alexa”? |

| Do you now know how to use “Alexa”? | |

| Do you now use “Alexa” with our newsletters more often than before? | |

| Features | Have you tried out new features with “Alexa”? |

| Have you tried video telephony? | |

| Reservations | Do you still feel you are being monitored or followed? |

| Guiding question: | Please tell us about your experience with “Alexa”? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | What do you enjoy about “Alexa”? |

| What don’t you enjoy about “Alexa”? | |

| Can you think of anything else? | |

| And what else? | |

| Is there anything else you can tell us? | |

| What do members of the complementary household have to say? | |

| Do you find “Alexa” intrusive? | |

| Contents | Questions |

| Intention and attitude | Would you buy an “Alexa” for yourself? |

| Would “Alexa” be good in other rooms of your home? | |

| Would you recommend “Alexa” to relatives/acquaintances/friends, and what would you say to them? | |

| Do you continue using “Alexa” after the test period? | |

| Do you want to keep the device? | |

| Usage | For what purposes do you use “Alexa”? |

| How often do you use “Alexa”? | |

| Simplicity | How do you find the use of “Alexa”? |

| Was it easy to learn to use “Alexa”? | |

| Did you research “Alexa features” beyond the newsletter? | |

| Did you need to seek help from complementary households or others? | |

| Information and system satisfaction/quality | Are you satisfied with the information you receive from “Alexa”? |

| Which functions do you particularly like, and which do you dislike? | |

| Reliability | Do you think “Alexa” works reliably? |

| Flexibility | Would you like “Alexa” to have certain additional functions? |

| Integration | How has “Alexa” integrated into your daily life? |

| Has your contact behavior changed due to video telephony with “Alexa”? | |

| Are there certain circumstances in which you use “Alexa”? | |

| Do you use “Alexa” to pass the time out of boredom or loneliness? | |

| Reservations/Privacy | Do you have reservations in connection with “Alexa”? |

| Do you feel that “Alexa” restricts your privacy? | |

| Personification | Has “Alexa” annoyed you? |

| Does “Alexa” seem like a technical device to you? | |

| Comparison to other digital technologies | How do you find “Alexa” compared to the smartphone? |

| For which purposes would you prefer “Alexa” to the smartphone? | |

| For which purposes would you prefer to use the smartphone/tablet or the PC? |

| Guiding question: | Please share your thoughts on your relative/friend/acquaintance’s experience with “Alexa”? |

| Maintaining the conversation: | What else? |

| Is there anything else you can tell us? | |

| Do you think your relative/acquaintance/friend got along well with “Alexa”? | |

| Have you been asked for help by your relative/acquaintance/friend? | |

| Did you use video telephony with your relative/acquaintance/friend? | |

| Who took the initiative to use the video telephony function? |

References

- Yu, J.E.; Parde, N.; Chattopadhyay, D. “Where is history”: Toward Designing a Voice Assistant to help Older Adults locate Interface Features quickly. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; Schmidt, A., Väänänen, K., Goyal, T., Kristensson, P.O., Peters, A., Mueller, S., Williamson, J.R., Wilson, M.L., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Bradley, S.; Weiner-Light, S.; Kwasny, M.; Mohr, D.; Lindquist, L. Voice intelligent personal assistant for managing social isolation and depression in homebound older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, S108. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, A. Senioren in der Digitalen Welt, Germany. 2020. Available online: https://www.bitkom.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/bitkom-prasentation-senioren-in-der-digitalen-welt-18-08-2020.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Statista. Digitale Sprachassistenten—Statistik-Report zu Digitalen Sprachassistenten, Germany. 2023. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/studie/id/48227/dokument/digitale-sprachassistenten/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, F.u.J. Achter Altenbericht zur Lage der älteren Generation in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Ältere Menschen und Digitalisierung und Stellungnahme der Bundesregierung, Germany. 2020. Available online: https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/service/publikationen/achter-altersbericht-159918 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Stefanacci, R.G. Veränderungen im Körper beim Älterwerden. 2022. Available online: https://www.msdmanuals.com/de/heim/gesundheitsprobleme-bei-%C3%A4lteren-menschen/alterserscheinungen/ver%C3%A4nderungen-im-k%C3%B6rper-beim-%C3%A4lterwerden (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Pelizäus-Hoffmeister, H. Zur Bedeutung von Technik im Alltag Älterer; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Heung, S.; Azenkot, S.; Brewer, R.N. Studying Exploration & Long-Term Use of Voice Assistants by Older Adults. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; Schmidt, A., Väänänen, K., Goyal, T., Kristensson, P.O., Peters, A., Mueller, S., Williamson, J.R., Wilson, M.L., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Chen, D.; Threatt, J.G.; Gorham, A.; Munteanu, C. Does Alexa Live Up to the Hype? Contrasting Expectations from Mass Media Narratives and Older Adults’ Hands-on Experiences of Voice Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Glasgow, UK, 26–28 July 2022; Halvey, M., Foster, M.E., Dalton, J., Munteanu, C., Trippas, J., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.; Ankenbauer, S.; Hashmi, M.; Upadhyay, P. Examining Voice Community Use. Acm Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2024, 31, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Exploring How Older Adults Use a Smart Speaker-Based Voice Assistant in Their First Interactions: Qualitative Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e20427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, A.; Lazar, A.; Findlater, L. Use of Intelligent Voice Assistants by Older Adults with Low Technology Use. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2020, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Lee, C.C. The impact of aging on access to technology. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2007, 5, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago, S.; Neves, B.B.; Cowan, B.R. Voice assistants and older people. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces—CUI ’19, Dublin, Ireland, 22–23 August 2019; Cowan, B.R., Clark, L., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, D. Voice Controlled Devices and Older Adults—A Systematic Literature Review. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Design, Interaction and Technology Acceptance; Gao, Q., Zhou, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13330, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomann, A.; Wahl, H.W.; Zentel, P.; Heyl, V.; Knapp, L.; Opfermann, C.; Krämer, T.; Rietz, C. Potential and Pitfalls of Digital Voice Assistants in Older Adults With and Without Intellectual Disabilities: Relevance of Participatory Design Elements and Ecologically Valid Field Studies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coghlan, S.; Waycott, J.; Nui, L.; Caine, K.; Stigall, B. Swipe a Screen or Say the Word: Older Adults’ Preferences for Information-seeking with Touchscreen and Voice-User Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 33rd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Melbourne, VI, Australia, 30 November—2 December 2021; Buchanan, G., Davis, H., Muñoz, D., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordasco, G.; Esposito, M.; Masucci, F.; Riviello, M.T.; Esposito, A.; Chollet, G.; Schlogl, S.; Milhorat, P.; Pelosi, G. Assessing Voice User Interfaces: The vassist system prototype. In Proceedings of the 2014 5th IEEE Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Vietri sul Mare, Italy, 5–7 November 2014; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, A.C.; Schubert, T.; Lambrich, L.; Strathmann, C. Alexa, I Do Not Want to Be Patronized. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Würzburg, Germany, 19–22 September 2023; Lugrin, B., Latoschik, M., von Mammen, S., Kopp, S., Pécune, F., Pelachaud, C., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Raghavaraju, V.; Kanugo, J.; Handrianto, Y.P.; Shang, Y. Development and evaluation of a healthy coping voice interface application using the Google home for elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–15 January 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziman, R.; Walsh, G. Factors Affecting Seniors’ Perceptions of Voice-enabled User Interfaces. In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Mandryk, R., Hancock, M., Perry, M., Cox, A., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, J.; Jaskulska, A.; Skorupska, K.; Abramczuk, K.; Biele, C.; Kopeć, W.; Marasek, K. Older Adults and Voice Interaction. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; Brewster, S., Fitzpatrick, G., Cox, A., Kostakos, V., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.; Kolody, S.; Comeau, A.; Miguel Cruz, A. What does the literature say about the use of personal voice assistants in older adults? A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, D.; Wilhelm, S.; Gerl, A.; Ahrens, D. A Quantitative Study on Awareness, Usage and Reservations of Voice Control Interfaces by Elderly People. In Proceedings of the HCI International 2021—Late Breaking Papers: Cognition, Inclusion, Learning, and Culture, Cham, Switzerland, 24–29 July 2021; pp. 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskulska, A.; Skorupska, K.; Karpowicz, B.; Biele, C.; Kowalski, J.; Kopeć, W. Exploration of Voice User Interfaces for Older Adults—A Pilot Study to Address Progressive Vision Loss. In Proceedings of the Digital Interaction and Machine Intelligence. MIDI 2020, Warsaw, Poland, 9–10 December 2020; Biele, C., Kacprzyk, J., Owsiński, J.W., Romanowski, A., Sikorski, M., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollasch, D.; Weber, G. Age-Related Differences in Preferences for Using Voice Assistants. In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2021, Ingolstadt, Germany, 5–8 September 2021; Schneegass, S., Pfleging, B., Kern, D., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Johnson, J.G.; Charles, K.; Lee, A.; Lifset, E.T.; Hogarth, M.; Moore, A.A.; Farcas, E.; Weibel, N. Understanding Barriers and Design Opportunities to Improve Healthcare and QOL for Older Adults through Voice Assistants. In Proceedings of the 23rd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Virtual, 18–22 October 2021; Lazar, J., Feng, J.H., Hwang, F., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, L.M.; McGlynn, S.A.; Blocker, K.A.; Rogers, W.A. Perceptions of Digital Assistants From Early Adopters Aged 55+. Ergon. Des. Q. Hum. Factors Appl. 2020, 28, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigall, B.; Waycott, J.; Baker, S.; Caine, K. Older Adults’ Perception and Use of Voice User Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction, Fremantle, Australia, 2–5 December 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegl, J.; Gollasch, D.; Loitsch, C.; Weber, G. Designing VUIs for Social Assistance Robots for People with Dementia. In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2021, Ingolstadt, Germany, 5–8 September 2021; Schneegass, S., Pfleging, B., Kern, D., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, L.; Garschall, M.; Himmelsbach, J.; Tscheligi, M. Hands free-care free. In Proceedings of the 8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Fun, Fast, Foundational, Helsinki, Finland, 26–30 October 2014; Roto, V., Häkkilä, J., Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K., Juhlin, O., Olsson, T., Hvannberg, E., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocker, K.A.; Kadylak, T.; Koon, L.M.; Kovac, C.E.; Rogers, W.A. Digital Home Assistants and Aging: Initial Perspectives from Novice Older Adult Users. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2020, 64, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkova, M.; Martin-Hammond, A. Alexa is a Toy: Exploring Older Adults’ Reasons for Using, Limiting, and Abandoning Echo. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; Bernhaupt, R., Mueller, F.F., Verweij, D., Andres, J., McGrenere, J., Cockburn, A., Avellino, I., Goguey, A., Bjørn, P., Zhao, S., et al., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonila, K.; Martin-Hammond, A. Older adults’ perceptions of intelligent voice assistant privacy, transparency, and online privacy guidelines. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2020), Boston, MA, USA, 9–11 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mizak, A.; Park, M.; Park, D.; Olson, K. Amazon ’Alexa’ Pilot Analysis Report. 2017. Available online: https://fpciw.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2017/12/FINAL-DRAFT-Amazon-Alexa-Analysis-Report.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Sange, R.; von Wulffen, K. Senior Social Entrepreneurship; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. (Destatis: 14. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Deutschland), Germany. 2024. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsvorausberechnung/aktualisierung-bevoelkerungsvorausberechnung.html (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Schrape, J.F. Digitale Transformation; utb: Beiersdorf-Freudenberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Dathe, R.; Jahn, S.; Müller, L.S.; Exel, S.; Fröhner, C.; Herrmann, A. D21 Digital Index 2021/2022: Jährliches Lagebild zur Digitalen Gesellschaft, Germany. 2021. Available online: https://initiatived21.de/uploads/03_Studien-Publikationen/D21-Digital-Index/2021-22/d21digitalindex-2021_2022.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Kelle, U.; Kluge, S. Vom Einzelfall zum Typus: Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der Qualitativen Sozialforschung, 2., überarb. aufl. ed.; Vol. Bd. 15; Qualitative Sozialforschung; VS Verl. für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ethikkommission DGP e. V.. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pflegewissenschaft e. V. Fragen zur ethischen Reflexion, Germany. 2017. Available online: https://dg-pflegewissenschaft.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/FragenEthReflexion.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Schatzmann, L.; Strauss, A. Field Research. Strategies for a Natural Sociology. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Künemund, H.; Fachinger, U. Alter und Technik; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, D.; Wilhelm, S. Imparting Media Literacy to the Elderly Evaluating the Efficiency and Sustainability of a two-part Training Concept. In Proceedings of the Human Interaction & Emerging Technologies (IHIET-AI 2022): Artificial Intelligence & Future Applications, AHFE International, Virtual Conference, 21–23 April 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Jakob, D.; Dietmeier, M. Development of a senior-friendly training concept for imparting media literacy. In Proceedings of the INFORMATIK 2019: 50 Jahre Gesellschaft für Informatik—Informatik für Gesellschaft, Kassel, Germany, 23–26 September 2019; Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V.. Digitale Bildung: Bonn, Germany, 2019; pp. 699–710, ISBN 978-3-88579-688-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, J. Lernprozesse Älterer mit neuen Technologien: Ergebnisse des Projekts “S-Mobil 100”. In DIE-Zeitschrift für Erwachsenenbildung, Germany. 2014, pp. 50–51. Available online: https://www.fachportal-paedagogik.de/literatur/vollanzeige.html?FId=3217998 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Shalini, S.; Levins, T.; Robinson, E.L.; Lane, K.; Park, G.; Skubic, M. Development and Comparison of Customized Voice-Assistant Systems for Independent Living Older Adults; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, S.A.; Meier, A.; Cihan, S. Alexa, tell me more—About new best friends, the advantage of hands-free operation and life-long learning, 2020. In Proceedings of the Mensch und Computer 2020, MCI-WS05: Selbstbestimmtes Leben Durch Digitale Inklusion von Senioren Mittels Innovativer Digitaler Assistenzsysteme, Magdeburg, Germany, 6–9 September 2020; Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyto GmbH. Beyto Smart Speaker Studie 2020|Germany. 2020. Available online: https://www.beyto.com/smart-speaker-studie-2020/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Splendid Research GmbH. Digitale Sprachassistenten Eine Repräsentative Umfrage unter 1.006 Deutschen zum Thema Digitale Sprachassistenten und Smartspeaker, Germany. 2019. Available online: https://www.splendid-research.com/de/studien/studie-digitale-sprachassistenten/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Hoffmann, D. Review: Uwe Flick (2006). Triangulation. Eine Einführung. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria Category | Inclusion Criteria and Justification |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic Criteria | |

| Age | Participants must be 55+ years old, irrespective of marital status, gender, education level, income, or occupation. They should live alone to ensure an objective assessment of device usage without external influence from family members. |

| Residence | Participants must reside within 50 km of the research institution to minimize travel effort for interviews and enable quick technical support if needed. |

| Relatives and friends | Participants must have at least one relative or friend (not living in the same household) willing to participate as a complementary household (CH). Details are provided in Section 3.1.3. |

| Technical Criteria | |

| Internet connection | Participants must have a WiFi router connected to the internet to ensure device connectivity. |

| Owning devices | Participants or their relatives/friends must own a smartphone or tablet capable of running the “Alexa App” to access additional digital services. Without a compatible device, usage is limited. |

| Amazon account | Necessary for device setup. If unavailable, the research team can assist in creating one. |

| Planned sample size | 20 SHs and 20 corresponding CHs. |

| ID ∑(n = 32) | Age | Gender Male (M) Female (F) | Life Situation Marital Union / Cohabitation (M) Living Alone (A) | Technologies Used Smartphone (S) Tablet (T) PC/Notebook (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 61 | F | A | S, T |

| P2 | 75 | M | M | S |

| P3 | 71 | F | M | — |

| P4 | 82 | M | M | S, T, P |

| P5 | 82 | F | M | S, T, P |

| P6 | 74 | F | M | — |

| P8 | 66 | F | A | S, P |

| P9 | 61 | F | A | S, P |

| P10 | 61 | M | A | S, T |

| P11 | 61 | M | M | S, T, P |

| P12 | 57 | F | M | S |

| P13 | 63 | F | M | S, P |

| P14 | 70 | M | M | S, P |

| P15 | 68 | M | M | S, P |

| P16 | 69 | F | M | S, T, P |

| P17 | 63 | M | M | P |

| P18 | 62 | F | M | S |

| P19 | 76 | M | A | S, T, P |

| P20 | 63 | F | A | S, T, P |

| P21 | 67 | F | A | S, T, P |

| P22 | 68 | M | M | S, T |

| P23 | 62 | F | M | S |

| P24 | 74 | M | M | P |

| P25 | 69 | F | M | S, T, P |

| P26 | 70 | M | M | S, T, P |

| P27 | 70 | F | M | S, T, P |

| P28 | 57 | F | M | S |

| P29 | 62 | M | M | S |

| P30 | 77 | M | A | P |

| P31 | 70 | M | M | S |

| P32 | 70 | F | M | S, P |

| = 68 | ∑ M: 15 | ∑ A: 8 | ∑ S: 27 | |

| SD: 6.75 | ∑ F: 17 | ∑ M: 24 | ∑ T: 13 | |

| ∑ P: 19 |

| Top-Code | Explanation and Example |

|---|---|

| Weather outlook/weather report | Questions about weather forecasts. Example: “Alexa, what will the weather be like in XX?” |

| Radio stations and music tracks | Commands to play radio stations or specific songs. Example: “Alexa, play XX.” |

| Knowledge in reference works | General knowledge inquiries. Example: “Alexa, what is the highest mountain in the world?” |

| Other information | Queries about varied topics such as time, COVID-19 statistics, or translations. Example: “Alexa, what are the incidence values in XX?” |

| System commands | Commands for volume control, canceling interactions, and settings. |

| Latest news | Requests for current news. Example: “Alexa, show me the news.” |

| Alarms and timers | Commands to set alarms or timers. Example: “Alexa, set an alarm for 7 o’clock.” |

| Cuisine recipes | Requests for recipes. Example: “Alexa, give me a recipe for currywurst.” |

| Reminders, appointments, notes | Commands to manage reminders or notes. Example: “Alexa, remind me of my doctor’s appointment.” |

| Communication | Phone or video calls. Example: “Alexa, call my daughter.” |

| Smart home device control | Commands for controlling smart home devices. Example: “Alexa, switch on the socket.” |

| Skills | Third-party information retrieval. Example: “Alexa, what is the animal of the day?” |

| Command incorrect | Commands not recognized by the VCD. Example response: “I’m not sure.” |

| Command understood | Correctly recognized and executed commands. Example response: “OK!” |

| Wrong answer/answer not known | Incorrect or unknown responses. Example: “Unfortunately, I don’t know that.” |

| SH-ID | Incorrect Commands | Understood Commands | Sum | Error Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∑ (n = 20) | 589 | 11,066 | 12,556 | 4.9 |

| 29.4 | 553.3 | 628 | 4.4 |

| Time of Day | Early | Morning | Noon | Afternoon | Evening | Night |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commands (n = 12,556) | 2907 | 2401 | 2777 | 2517 | 1653 | 301 |

| Percentage (%) | 23.2 | 19.1 | 22.1 | 20.0 | 13.2 | 2.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jakob, D.; Wilhelm, S.; Gerl, A.; Ahrens, D.; Wahl, F. Adapting Voice Assistant Technology for Older Adults: A Comprehensive Study on Usability, Learning Patterns, and Acceptance. Digital 2025, 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital5010004

Jakob D, Wilhelm S, Gerl A, Ahrens D, Wahl F. Adapting Voice Assistant Technology for Older Adults: A Comprehensive Study on Usability, Learning Patterns, and Acceptance. Digital. 2025; 5(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital5010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleJakob, Dietmar, Sebastian Wilhelm, Armin Gerl, Diane Ahrens, and Florian Wahl. 2025. "Adapting Voice Assistant Technology for Older Adults: A Comprehensive Study on Usability, Learning Patterns, and Acceptance" Digital 5, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital5010004

APA StyleJakob, D., Wilhelm, S., Gerl, A., Ahrens, D., & Wahl, F. (2025). Adapting Voice Assistant Technology for Older Adults: A Comprehensive Study on Usability, Learning Patterns, and Acceptance. Digital, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital5010004