Effects of Implementing the Digital Storytelling Strategy on Improving the Use of Various Forms of the Passive Voice in Undergraduate EFL Students’ Oral Skills at the University Level

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Instrument 1: PISA Benchmarking Test

3.2.2. Instrument 2: Pretest/Posttest Models per Target Passive Units

3.3. Treatment

3.3.1. Treatment for the Experimental Group (EG)

- -

- Pre-watching the digital story:

- -

- Watching the digital story:

- At what age was Aissata cut?

- Why were the girls cut in her culture?

- How was the female genital cut (FGC) done in the story?

- Who founded the education program to end FGC?

- Was FGC abandoned in Aissata’s community after joining the program, and why?

- -

- Post Watching the Digital Story:

3.3.2. Treatment for the Control Group

4. Results

4.1. PISA Test Results

4.2. Pre- and Posttests Results

- Control group: Pretest and Posttest Score Differences

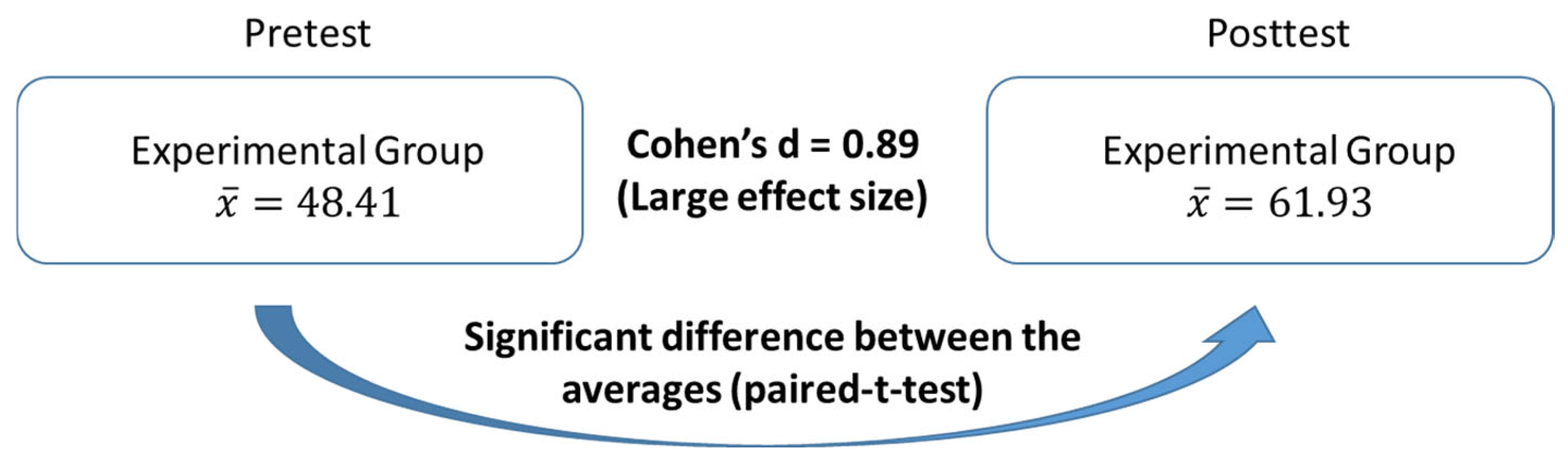

- Experimental group: Pretest and Posttest Score Differences

- Comparison between Control Group and Experimental Group Results.

- The Shapiro–Wilk test of normality showed that the student scores for both the control group and experimental group were normally distributed (p-value = 0.31, p-value = 0.92).

- The Fisher’s test of equality of variance showed that the student’s scores had the same variance for both the control group and experimental group (p-value = 0.15 > 0.05).

5. Discussion

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mckay, S. Teaching English as an International Language: Rethinking Goals and Approaches, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.A. Role of Applied Linguistics in the Teaching of English in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 2011, 1, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, J.; Macaro, E. Higher Education Teachers’ Attitudes towards English Medium Instruction: A Three-Country Com-parison. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2016, 6, 455–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, I.; Rose, H. An Analysis of Japan’s English as Medium of Instruction Initiatives within Higher Education: The Gap between Meso-Level Policy and Micro-Level Practice. High. Educ. 2018, 77, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C.; Kettle, M.; May, L.; Caukill, E. Talking the Talk: Oracy Demands in First Year University Assessment Tasks. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2011, 18, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. Business Graduate Performance in Oral Communication Skills and Strategies for Improvement. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esseili, F. A Sociolinguistic Profile of English in Lebanon. World Englishes 2017, 36, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, K.A. Disparity between Ideals and Reality in Curriculum Construction: The Case of the Lebanese English Lan-guage Curriculum. Creat. Educ. 2013, 04, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahous, R.; Bacha, N.; Nabhani, M. Motivating Students in the EFL Classroom: A Case Study of Perspectives. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2011, 4, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, N. Is the Grammar-Instruction Approach an Old-Fashioned Method in Comparison to the Communicative Ap-proach in Non-Native Contexts? A Case Study of Students and Teachers’ Perceptions. CALR Linguist. J. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Raba’a, B.I.M. The grammatical influence of English on Arabic in the passive voice in translation. Int. J. Linguist. 2013, 5, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmanafi-Rokni, S.J. Digital Storytelling in EFL classrooms: The effect on the oral performance. Int. J. Lang. Linguist. 2014, 2, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeda, N.; Dakich, E.; Sharda, N. The Effectiveness of Digital Storytelling in the Classrooms: A Comprehensive Study. Smart Learn. Environ. 2014, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, H.; Chen, H. Digital Storytelling in Language Education. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallinikou, E.; Nicolaidou, I. Digital Storytelling to Enhance Adults’ Speaking Skills in Learning Foreign Languages: A Case Study. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2019, 3, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, N.; Tomita, Y. Interactions between type of instruction and type of language feature: A meta-analysis. Lang. Learn. 2010, 60, 263–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaji, H.; Fotos, S.S. Teaching Grammar in Second Language Classrooms: Integrating Form-Focused Instruction in Communicative Context, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikroni, M.R. Grammatical competence within L2 communication: Language production, monitor hypothesis, and focus on forms instruction. Pancar. Pendidik. 2018, 7, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Q. 2006, 40, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. Teaching Language: From Grammar to Grammaring, 1st ed.; Thomson: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Muziatun Malabar, F.; Mustapa, L. Analyzing students’ passive voice difficulties. Indones. EFL J. 2022, 8, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-M.; Ahmadi, S.M. An analysis of factors influencing learners’ English speaking skill. Int. J. Res. Engl. Educ. 2017, 2, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A. Transformational Grammar: A First Course (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics); Cambridge University Press: Cam-bridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, F. Speaking Competence and Its Components: A Review of Literature. Int. J. Res. Linguist. Lang. Teach. Test. 2016, 1, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.; Basturkmen, H.; Loewen, S. Doing focus-on-form. System 2002, 30, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruneanu, M.D.; Lemnaru, A.C.; Dina, A.T. A view on grammar teaching and practice for communicative activities in Romanian as foreign language acquisition in online classroom. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2022, 14, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhoue, L. To teach or not to teach grammar A controversy? CALR Linguist. J. 2016, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F. In defense of the passive voice. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unver, M.M. On Voice in English: An Awareness Raising Attempt on Passive Voice. Eur. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S. Changing approaches to teaching grammar. Engl. Lang. Teach. Educ. Dev. (ELTED) 2008, 11, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bancolé-Minaflinou, E. Exploring the teaching of communicative grammar in EFL classes in Benin to promote language use in CBA Context. World J. Educ. 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoz, A.; Elola, I. Digital stories in L2 education: Overview. CALICO J. 2016, 33, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyani, E.P.; Al Arief, Y.; Amelia, R.; Asrimawati, I.F. Enhancing students’ speaking skill through digital storytelling. J. Engl. Teach. Appl. Linguist. Lit. (JETALL) 2022, 5, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eragamreddy, N. Passive Voice Teaching: Recent Trends and Effective Strategies. Stud. Humanit. Educ. 2024, 5, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garraffa, M.; Smart, F.; Obregón, M. Positive effects of passive voice exposure on children’s passive production during a classroom story-telling training. Lang. Learn. Dev. 2021, 17, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.C.M.; Burns, A. Teaching Speaking: A Holistic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ginting, D.; Sabudu, D.; Barella, Y.; Woods, R. The place of storytelling research in English language teaching: The state of the art. Voices Engl. Lang. Educ. Soc. 2023, 7, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iluk, J.; Jakosz, M. Storytelling and its effectiveness in developing receptive skills among children. Stud. Linguist. Univ. Iagell. Cracoviensis 2017, 134, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risdayani, N.; Limbong, E.; Sunggingwati, D. EFL pre-service teachers’ experiences in speaking through a digital storytell-ing project. Jambura J. Engl. Teach. Lit. 2024, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fàbregues, S.; Mumbardó-Adam, C.; Escalante-Barrios, E.L.; Hong, Q.N.; Edelstein, D.; Vanderboll, K.; Fetters, M.D. Mixed Methods Intervention Studies in Children and Adolescents with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: A Methodological Review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 126, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, K.; Tulloch, H. Strengthening Behavioral Clinical Trials with Online Qualitative Research Methods. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 25, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Before | Before | Treatment | After |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | PISA Test | Pretest |

| Posttest |

| Control Group |

|

| Categories of Activity I in the Posttest | Average Scores of the Experimental Group in Activity I of the Posttest | Average Scores of the Control Group in Activity I of the Posttest |

|---|---|---|

| Proper usage of passive voice with yes/no questions (/12) | 7.83 | 2.64 |

| Proper usage of passive with modals (/6) | 5.46 | 2.73 |

| Proper usage of passive causative (the passive causative form with the appropriate form of “have” or “get” + object + past participle) (/15 pts) | 12.63 | 7.73 |

| Pronunciation (pronunciation is accurate, with correct inflections, numbers of syllables, and other correct nuances of pronunciation) (/2.5 pts) | 1.75 | 1.23 |

| Fluency (the student should speak confidently and clearly with no distraction; ideas should flow smoothly) (/2.5 pts) | 1.75 | 1.23 |

| Relevant content and organization (recording includes a central theme, a clear point of view, and a logical sequence of information; events and messages are presented in a logical order, with relevant information that matches the video’s main transcript) (/7 pts) | 5.92 | 3.68 |

| Clarity of voice (/2.5 pts) | 2.33 | 1.59 |

| Duration (2–3 min) (/2.5 pts) | 2.5 | 1.95 |

| Total (/50 pts) | 40.16/50 | 22.77/50 |

| Categories of Pretest and Posttest Activity II | Average Scores of the Experimental Group in Task II of the Posttest | Average Scores of the Control Group in Task II of the Posttest |

|---|---|---|

| Accurate usage of passive with modals in an affirmative form (/2 pts): | 1.83 | 1.45 |

| Accurate usage of passive with similar expressions (4/ pts): | 2.96 | 1.77 |

| Form the simple past passive (/4 pts) | 3.5 | 2.5 |

| Accurate usage of passive causative (/4 pts): | 3.13 | 1.77 |

| Pronunciation (pronunciation is accurate, with correct inflections, numbers of syllables and other correct nuances of pronunciation) (/2 pts) | 1.63 | 1.14 |

| Fluency (the student should speak confidently and clearly with no distraction; ideas should flow smoothly) (/2 pts) | 1.58 | 1.18 |

| Edited recording content (the student’s recording matches the content of the given letter, and the corrected six errors in the use of the passive are integrated into the recorded complaint letter.) (/3 pts) | 2.96 | 2.36 |

| Clarity of voice (/2 pts) | 1.83 | 1.45 |

| Duration (1 min) (/2 pts) | 1.88 | 1.59 |

| Total (/25) | 21.29/25 = 42.58/50 | 15.22/25 = 30.45/50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez-Colón, M.; Alameh, S.A. Effects of Implementing the Digital Storytelling Strategy on Improving the Use of Various Forms of the Passive Voice in Undergraduate EFL Students’ Oral Skills at the University Level. Digital 2024, 4, 914-931. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4040045

Gutiérrez-Colón M, Alameh SA. Effects of Implementing the Digital Storytelling Strategy on Improving the Use of Various Forms of the Passive Voice in Undergraduate EFL Students’ Oral Skills at the University Level. Digital. 2024; 4(4):914-931. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4040045

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez-Colón, Mar, and Sahar Abboud Alameh. 2024. "Effects of Implementing the Digital Storytelling Strategy on Improving the Use of Various Forms of the Passive Voice in Undergraduate EFL Students’ Oral Skills at the University Level" Digital 4, no. 4: 914-931. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4040045

APA StyleGutiérrez-Colón, M., & Alameh, S. A. (2024). Effects of Implementing the Digital Storytelling Strategy on Improving the Use of Various Forms of the Passive Voice in Undergraduate EFL Students’ Oral Skills at the University Level. Digital, 4(4), 914-931. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4040045