1. Introduction

In today’s digital age, cyber security has emerged as a critical concern for businesses worldwide. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face unique vulnerabilities to cyber threats due to their limited resources and expertise in cyber security. This susceptibility is further compounded by the absence of robust governance and policy frameworks in many countries, hindering effective mitigation of cyber security risks. As Industry 5.0 revolutionizes the industrial landscape, it not only builds upon the technological advancements of Industry 4.0 but also aims to reintroduce the human element in production. Industry 5.0 seeks to personalize the industry by leveraging the creativity of human experts working collaboratively with efficient, intelligent, and precise machines [

1].

Within this context, Saudi Arabia’s SME landscape is rapidly evolving and flourishing [

2]. The country has become a central hub for cyber security practices, particularly among SMEs that operate online. However, this increased online presence exposes SMEs to a broader threat landscape as they engage more extensively with the internet, making them susceptible to attacks. While Saudi Arabia undergoes cultural and developmental changes, academic research has played a significant role in promoting effective working practices, contributing to economic growth within the Saudi Arabian business environment. Nevertheless, the evolving digital infrastructure and data management practices have left SMEs increasingly vulnerable to cyberattacks as numerous online doors open up. This comparative research study aims to explore the resistance of SMEs to cyber security, with a specific emphasis on governance and policy, in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom. Both countries boast vibrant SME sectors and have made notable advancements in the development of cyber security policies. However, variations exist in the level of resistance and the approaches adopted by SMEs in addressing cyber security challenges.

Saudi Arabia, given its geopolitical prominence, wealth, and technological dependence, has emerged as a prime target for cyberattacks. With 93% of its population actively using the internet and 72% engaged in social media, Saudi Arabia ranks among the countries with the highest internet usage rates [

3]. Disturbingly, reports indicate that in 2018 alone, Saudi Arabia faced approximately 160,000 cyberattacks targeting its servers daily [

4]. These attacks contributed to a 4% increase in malware attacks and an alarming 378% surge in ransomware incidents [

5]. The severity of cyber threats continued to escalate in subsequent years, leading to Saudi Arabia ranking as the second-highest country in terms of breached data in 2019 and 2020, incurring significant financial costs [

6]. Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the Saudi Arabian government issued a royal order to establish a specialized authority responsible for cyber security and governance. Notably, Saudi Arabia has introduced a crucial governance framework known as the Essential Cybersecurity Controls (ECC-1:2018) to safeguard business data [

7]. This research seeks to gain deeper insights into SMEs’ utilization of the ECC document and their compliance in adopting cyber security practices to effectively navigate the associated challenges.

The primary objective of this research is to explore the factors contributing to SME resistance to cyber security and assess how governance and policy frameworks can help SMEs overcome these barriers. The study will analyze the cyber security landscape in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom, encompassing the regulatory environment, industry practices, and available resources. Furthermore, it will examine the challenges faced by SMEs in implementing cyber security policies and identify best practices to address these challenges. The research will involve surveying SME participants, with the sample representing SME businesses in Saudi Arabia. Statistical analysis will be applied to the collected data, employing a mixed-method approach that combines quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. Cross-tabulation will aid in identifying patterns and trends within the collected data. SMEs will be queried regarding their familiarity with the ECC document and whether they possess the necessary tools to establish cyber resilience. Participants will also be probed about their attitudes toward governance using the ECC document and how they measure their digital confidence in making informed decisions while implementing cyber security controls to protect their businesses. Additionally, the research will explore SMEs’ awareness of cyber security, emphasize the importance of security, and examine the inclination of SMEs toward resistance or willingness to adopt a proactive security mindset. Furthermore, the study will explore how Saudi Arabia’s cyber security agencies can bolster SMEs’ digital confidence in effectively addressing complex cyber security challenges. Comparisons will also be drawn with the United Kingdom, a developed nation grappling with escalating cyber threats, to evaluate the efficacy of governance and policy frameworks in safeguarding SMEs. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides background and theoretical context,

Section 3 reviews relevant work and prior assessments that inform this research,

Section 4 outlines the methodology and experimental approaches employed to evaluate the hypothesis,

Section 5 presents the discussion and safety analysis, and the concluding section summarizes the findings and outlines future work. Ultimately, this research aims to offer insights that inform the development of effective cyber security governance and policy frameworks for policymakers, SMEs, and stakeholders. By enhancing cyber resilience among SMEs, we can effectively combat cyber threats, foster innovation, and drive sustainable economic growth.

2. Background and Theoretical Context

2.1. Industry 4.0 and 5.0

Industry 5.0 represents the next phase of industrial development and refers to the integration of human capabilities with advanced technologies in the manufacturing sector. It focuses on restoring the human aspect in production by emphasizing collaboration between human workers and intelligent machines. Unlike Industry 4.0, which primarily focused on digitization and automation, Industry 5.0 aims to combine the strengths of humans and machines to achieve greater efficiency, precision, and innovation in manufacturing processes. It recognizes the importance of human creativity, problem-solving skills, and adaptability in driving productivity and competitiveness. Industry 5.0 seeks to create a symbiotic relationship between humans and machines, where humans provide the expertise, intuition, and emotional intelligence, while machines provide speed, accuracy, and data-driven insights. This shift towards a more human-centric approach in Industry 5.0 marks a departure from the fully automated and digitized systems of Industry 4.0, allowing for more personalized and flexible production processes [

8,

9,

10].

2.2. Cyber Security for SMEs in Saudi Arabia

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a vital role in the economy of Saudi Arabia, accounting for approximately 90% of all businesses in the country [

11]. However, these businesses are often more vulnerable to cyber-attacks than larger organizations due to their limited resources and less robust cyber security measures. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has recognized the importance of protecting its critical infrastructure and digital assets and has implemented various initiatives to improve cyber security in the country. In 2017, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) issued a set of regulations for cyber security in the banking sector, which included guidelines for incident reporting and response, risk assessment, and cyber security training for employees [

12,

13]. In 2019, the National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) was established to oversee the country’s cyber security strategy and coordinate efforts among different government agencies and the private sector [

14]. The theoretical context for cyber security in SMEs in Saudi Arabia is grounded in the broader field of cyber security and information security. This field encompasses various disciplines, including computer science, cryptography, risk management, and human factors. The core objective of cyber security is to protect digital assets and information systems from unauthorized access, theft, and damage in the context of preserving the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) of data. One of the major challenges in cyber security is the constantly evolving nature of cyber threats. Attackers use a wide range of techniques, including malware, phishing, social engineering, and ransomware, to exploit vulnerabilities in computer networks and systems. To counter these threats, cyber security professionals use a variety of tools and techniques, including firewalls, intrusion detection and prevention systems, encryption, and security awareness training. In the context of SMEs, cyber security poses unique challenges due to limited resources and lack of awareness. SMEs often have fewer employees and smaller budgets than larger organizations, making it difficult for them to implement comprehensive cyber security measures. Moreover, many SMEs may not be aware of the latest cyber threats and best practices for cyber security, leaving them vulnerable to attacks. To address these challenges, cyber security professionals must develop tailored strategies that consider the unique needs and constraints of SMEs. This may involve simplifying cyber security measures, providing training and education to employees, and leveraging cloud-based solutions to reduce costs and improve security. Ultimately, the goal is to ensure that SMEs in Saudi Arabia can operate securely and confidently in an increasingly digital and interconnected world.

In Saudi Arabia, SMEs are defined as businesses that employ 249 or fewer staff, but not fewer than 7 employees, and have less than SR200 m (

$53.3 m) but more than SR3 m (

$0.7 m) in annual revenue [

15]. The number of SMEs has also increased by 68%, reaching 752,500 during quarter one of 2022, considering the government incentives provided by Vision 2030. The government of Saudi Arabia has provided opportunities to use the internet to drive the adoption of technology, data, and artificial intelligence to deliver government services to citizens, non-citizens, and the public and private sectors as part of this vision. However, the challenges SMEs are facing, such as having a low budget, not having enough resources, having a lack of skills, not knowing that they are targeted by hackers, and having a lack of understanding, amongst others, lead to SMEs being vulnerable both globally and in Saudi Arabia. Oil giant Aramco is one example of a large organization that has suffered and continues to suffer from cyber-attacks in Saudi Arabia. In 2012, Aramco was a victim of a virus attack identified as the “Shamoon” virus. An estimated 30,000 Windows-based machines operating on the corporate network were damaged by the chaos of the virus. There was no reported incident such as an oil spill or drilling error; however, vast amounts of data were lost due to this attack. SMEs can certainly learn from the lessons of the larger organizations and can therefore apply and further learn to protect themselves. If this is put into perspective, Aramco is part of a critical global area for gas and oil production, and as a result, nearly half of the top oil producers from this region were at risk, particularly as their supply chain consisted of thousands of SMEs [

16]. In 2018, the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia also experienced a Denial of Service (DoS) attack on their website. The Ministry of Health serves and provides the internal infrastructure of the health care service of Saudi Arabia, which makes this infrastructure a crucial building block for the country. In general, approximately 94% of the companies in the Middle East and Africa stated that they had been a victim of a cyber-attack in 2018 [

17]. Saudi Arabian organizations face problems anticipating, detecting, mitigating, and/or preventing cyber-attacks despite policies and regulations. This was mainly due to these organizations not investing in cyber security.

Saudi Arabia had also recently introduced a new data protection law called the “Personal Data Protection Law.” The law came into effect on 30 July 2020, and its aim is to ensure the protection of individuals’ personal data by regulating the collection, processing, and storage of such data. Under this law, organizations are required to obtain consent from individuals before collecting, processing, or sharing their personal data. Additionally, organizations must take measures to ensure the security and confidentiality of personal data and to prevent unauthorized access, use, or disclosure of such data.

The law also establishes a Personal Data Protection Authority, which is responsible for enforcing the provisions of the law and ensuring compliance. Violations of the law can result in fines and penalties, as well as potential civil or criminal liability.

This law is part of a broader initiative in Saudi Arabia to modernize its legal framework and promote digital transformation. The country has also recently introduced other laws and regulations related to e-commerce, cyber security, and intellectual property, among other areas.

According to a recent study of Saudi Arabia’s security infrastructure, security management is often outsourced to overseas organizations due to a lack of in-house management skills within the country, leading to high security risks. These outsourced IT managers lack the knowledge and skills for proactive cyber strategies and are far removed from the business in terms of communication and onsite experience [

18]. The findings highlight a lack of essential knowledge and skills in performing their expected roles well. Cyber security management weaknesses also exist in Saudi Arabia’s private organizations, and improving the quality of computer security systems can be a course of action. To remedy this, useful courses and workshops to attain the knowledge and skills can be offered by various international organizations to train the internal workforce of Saudi Arabia. These methods would give the support required to address the skills shortage of SMEs and larger organizations. However, what would be more worthwhile is having these in-house skills to perform these same duties within the country rather than outsourcing the skills elsewhere.

2.3. Monsha’at and the NCA

Monsha’at, also known as the Saudi Arabian General Authority for Small and Medium Enterprises, is a government agency in Saudi Arabia that aims to support and develop small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the country. Monsha’at was established in 2015 by a royal decree, and its responsibilities include providing financial and technical support, promoting entrepreneurship, and facilitating access to markets for SMEs. The National Cybersecurity Agency (NCA) is another government agency in Saudi Arabia that was established in 2017 to enhance cyber security and protect national critical infrastructure from cyber threats. The NCA is responsible for developing and implementing national cyber security policies, strategies, and standards, as well as coordinating and collaborating with other government agencies, private sector organizations, and international entities on cyber security matters. The establishment of both Monsha’at and the NCA reflects the Saudi government’s commitment to promoting economic development and protecting national security in the digital age. By supporting SMEs, Monsha’at aims to create jobs, drive innovation, and diversify the economy, while the NCA seeks to safeguard the country’s digital infrastructure and assets from cyber threats such as hacking, espionage, and cyberterrorism [

19,

20].

Table 1 shows how these two agencies collaborate and bring together the community of SMEs and cyber security governance and compliance towards the ECC document and its contribution towards keeping Saudi Arabia cyber secure.

For Saudi Arabia to comply, the NCA was established, and its mandate was approved as per the “Royal Decree number 6801, dated 11/2/1439H making it the national and specialized reference for matters related to cyber security in the kingdom” as referenced in

Table 1. The Essential Cyber Security Controls (ECC-1:2018) (ECC) is a document that was published by the National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) in Saudi Arabia in 2018. It outlines a set of minimum cyber security controls that organizations in the country should implement to protect themselves against cyber threats. The document is relevant to all organizations in Saudi Arabia, including SMEs, as cyber threats can affect organizations of all sizes. SMEs may be particularly vulnerable to cyber threats due to limited resources and expertise in cyber security. While it is not possible to determine whether all Saudi Arabian SMEs are using the ECC document, it is recommended that they do so to enhance their cyber security posture. Implementing these controls can help SMEs to protect their sensitive data, prevent cyber-attacks, and reduce the risk of financial losses and reputational damage. In addition, the NCA provides various resources and tools to help organizations in Saudi Arabia, including SMEs, to implement the ECC. These resources include guidelines, training programs, and cyber security assessments. SMEs can use these resources to enhance their cyber security capabilities and better protect themselves against cyber threats. Hence, the role of the ECC was to set the minimum cyber security requirements for national organizations within its scope of implementing the ECC. The ECC covers domains such as governance, defense, resilience, third party and cloud computing, and industrial control systems (ICS) and devices [

21]. From these five domains, subdomains take shape to guide businesses from policies on the use of technology and incident management and threat handling. Collectively, 29 subdomains are categorized, leading to 114 cyber security controls outlining strategies, roadmaps, and steering committees, to name a few. These controls take into consideration the following four main cyber security pillars: strategy, people, processes, and technology.

Monsha’at is Saudi Arabia’s SME General Authority, established in 2015 with the aim of “regulating, supporting, developing and sponsoring the SME sector in the kingdom in accordance with global best practices” with the view of increasing the productivity of SMEs and their contribution towards the growth of the country from 20% to 35% by 2030 [

22]. Monsha’at is a starting point for SMEs to gather information to run their businesses, and it offers plenty of training and education in running businesses. Whilst Monsha’at offers e-commerce programs and services, the cyber security service known as the “Thakaa” service has only recently been established in 2020. Here SMEs get a chance to gain some knowledge of cyber security through consultation and training for SMEs which need and seek this information. These services can only be tapped into by registering with Monsha’at to reap the full benefit of their programs that are free to SMEs in Saudi Arabia.

With a national increase in the number of SMEs in quarter 1 of 2022, the SMEs in Saudi Arabia increased by 68% following incentives provided by the government and its leaders, such as Vision 2030. Saudi Arabia is still considered a developing country, according to the definition from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), due to its lower economic performance; however, considering its human development index (HDI) score of 0.875, Saudi Arabia counts as one of the highest developed economies by the UN definition [

16]. Vision 2030 was born under the leadership of His Royal Highness the Crown Prince to harness strength, strategic position, and investment power and to be the center of the Middle Eastern countries. The aim to build a thriving economy for an ambitious nation living in a vibrant society will be the success of the country as it gains its developed status [

23]. Coupled with this, the cyber security industry globally is due to reach almost

$366.10 billion by 2028, and Saudi Arabia is predicted to also follow this trend. This growth will be approximately 12.4% between 2020 and 2026. Hence, the importance of cyber security will be clear as Saudi Arabia moves towards its Vision 2030 and move towards its own cyber security culture and mindset shift.

2.4. Cyber Security for SMEs in the United Kingdom (UK)

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the United Kingdom (UK) face a significant threat from cyber-attacks, and their security measures often lag behind those of larger corporations. The increasing use of technology and the internet in business operations has made SMEs particularly vulnerable to cyber-attacks, which can result in financial loss, reputational damage, and even business closure. Therefore, cyber security has become a crucial issue for SMEs in the UK. The theoretical context for cyber security for SMEs in the UK is rooted in several concepts, including risk management, information security, and cyber resilience. Risk management involves identifying and assessing risks and implementing strategies to mitigate them. Information security involves protecting sensitive and confidential information from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction. Cyber resilience refers to an organization’s ability to withstand and recover from cyber-attacks, including their ability to continue operating during and after an attack. The UK government has recognized the importance of cyber security for SMEs and has launched several initiatives to help SMEs improve their cyber security posture. The Cyber Essentials scheme, for example, is a government-backed certification that helps SMEs implement basic cyber security controls. The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) also provides guidance and support to SMEs through its Small Business Guide [

24]. In addition to government initiatives, there are several best practices that SMEs can implement to improve their cyber security posture. These include implementing strong passwords, regularly updating software and systems, backing up data, and providing cyber security awareness training to employees. Following these guidelines helps SMEs gain awareness and shape their business to keep their data as safe as can be. The guidelines follow a set of rules such as backing up SME data, protecting organizations from malware, keeping the Internet of Things (IoTs) safe, using well-structured passwords and management to protect the data, and avoiding phishing attacks, amongst many other tips and tricks. For the UK, these aspects of guidance and governance help SMEs develop a state of cyber awareness. Just like Saudi Arabia’s NCA, the NCSC equally provides this cyber security guidance and support, centrally helping to make the UK a safe haven to work online.

Much like Monsha’at, the UK has an equivalent organization called the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) representing SMEs in the UK [

25]. Established in 1974, the National Federation of Self Employed changed its name to the FSB in 1991. The FSB provides SMEs with complete business support, including online legal documents with over 1300 documents, templates, and policies on everything from tax to cyber security. The Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) is a UK-based membership organization that supports and advocates for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). One important area of concern for the FSB and its members is cyber security. Small businesses are often vulnerable to cyber-attacks due to limited resources and expertise in this area. According to a 2020 report by the FSB, almost half of small businesses in the UK experienced a cyber-attack in the previous two years, and the average cost of these attacks was £1300. To address this issue, the FSB provides guidance and resources to its members on how to improve their cyber security practices. This includes advice on password management, data protection, and the use of firewalls and antivirus software. The FSB also works with government agencies and other organizations to promote best practices and raise awareness of cyber security threats facing small businesses. At the start of 2021, the FSB recorded 5.5 million SMEs with 0 to 49 employees in the UK, overall contributing to 99.2% of the total business. SMEs account for 99.9% of the business population as shared by the FSB. With the continuous rise of SMEs in the UK, it has become more imperative than ever to make sure that SME business trading is kept safe and secure. FSB has also reported facts such as that UK SMEs suffer close to 10,000 cyber-attacks daily and were targeted by online criminals more in 2020 than in 2019, and those who needed to defend their business often had to do so several times. In fact, the survey found that 28% of the businesses that suffered attacks were targeted on more than five occasions in 2020. According to the FSB, 44% of SMEs have been targeted by fraudsters, with one in four businesses falling victim to fraud, resulting in a collective £18.9 billion estimated loss to UK SMEs. With SMEs forming the backbone of the UK economy, SMEs now make up three-fifths of the employment and half of turnover in the UK’s private sector. The SME ecosystem is proving to be an important one in the growth and economies of developed countries, therefore playing an even more important role in how their usage of emerging technologies is keeping their data and businesses safe online. The FSB is also supported locally within regions such as Wales and Scotland by other agencies such as Business Wales [

26] and the Scottish Enterprise [

27], respectively. Each agency is now dedicated to its infrastructure to better the process of SMEs attaining knowledge on cyber security and how support can be gained through these channels to work with SMEs to give them the security they need. Cyber prime organizations that are large in nature and have the infrastructure in place for cyber security also are becoming a beacon of leadership in terms of learning how SMEs can follow suit in becoming secure. University bodies also offer a platform with which to engage talent and act as a resourcing pool for SMEs to dip into for research and development to grow their business safely.

With recent changes to the law such as Brexit, the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Cyber Essentials practices, and many more government-run initiatives for governance, SMEs are struggling to understand the bigger importance of how intelligent software is now required to keep their businesses secure [

28].

Table 2 shows the many policies of government support there are in the UK and EU in terms of data protection and the existence of this governance is marked with an X.

From

Table 2, the list of governance aspects is clear in its usage within the UK and in the EU.

Table 2 starts with the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR), followed by the Online Safety Bill and Data Protection Act. As one of the most wide-ranging pieces of EU legislation across the single market, the GDPR was introduced to standardize data protection laws to give greater control over personal data and how it is used in a growing digital economy. Although originally passed in the EU, the principles-based approach affects businesses worldwide and includes fairness, lawfulness and transparency, purpose limitation, data minimalization, accuracy, storage limitation, integrity, confidentiality (security), and accountability. At a time when more people are entrusting their personal data via cloud services with daily occurrences of data breaches, Europe is signaling a strong stance for data privacy and security. The specific regulations make compliance a daunting prospect for SMEs. Policies such as ISO27001 and Cyber Essentials function as guidance, and whilst larger businesses are able to comply, SMEs still face the struggle of implementation due to a lack of resources and financial strength within their organizations [

30]. Overall, cyber security for SMEs in the UK is a complex issue that requires a multi-faceted approach, including government support, best practices, and cyber resilience strategies.

3. Related Work

Hassan et al. (2022) explores reflections on the use of digital technology and how important it has become and how essential and unavoidable for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Saudi Arabia [

31]. They discuss the use of technology and how it brings risks and opportunities; ways in which to control the risk, given the appropriate information security risk assessment methodology; and how this can then be applied within the business. Hassan’s paper also discusses the importance of confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA triad) and how it helps in assessing the risks and identifying the security requirements to protect information and data. To complement this, being able to identify vulnerabilities in systems and defend against threats eventually helps reduce risks and supports the control of the level of insecurity faced by NGOs. Meeting these standards requires knowledge and experience in information security management and how this is now the challenge faced by most NGOs in Saudi Arabia. Hassan et al. conducted a survey in which 168 NGOs that were accredited by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (MHRSD) in Saudi Arabia were selected using a multi-stage stratified sampling method. The results indicated a lack of security awareness regarding information security protection and the NGOs’ need for a simpler tool in order to support information security risk with the limited expertise and resources available. NGOs and SMEs are very similar in structure; they both have few/no resources due to their lack of finances for securing security professionals, consulting, and offering training services. The lack of funding also leads to poor security solutions and poor knowledge of the subject matter due to training gaps, as explored in Hassan’s research.

In the UK, Rawindaran et al. [

32] highlighted the challenges of human behavior online and how it is growing exponentially, making it difficult to track and store information and thus increasing vulnerability to online crimes such as phishing. Rawindaran et al. also investigated the challenges end-users in SMEs faced when adopting intelligent software to combat cybercrimes such as phishing and malware. Their research found that while intelligent software has been successfully deployed in many monitoring applications, SME end-users are still underutilizing these techniques. Rawindaran et al. found that some small businesses did not know or pay attention to the fact that artificial intelligence and machine learning were built into the cyber security solutions they were investing in. Rawindaran et al. recommended that an awareness of intelligent software in cyber security, such as through education and training, should be improved among companies to protect themselves and their end-users from cybercrime. Rawindaran et al. explored cyber security technology issues using mixed methods to create a study of smart software adoption among users in an enterprise setting.

In another study by Rawindaran et al., a mixed-method approach using quantitative and qualitative methods was implemented to explore the challenges to businesses adopting intelligent software to combat cybercrime within the SME ecosystem [

33]. The research here suggested that cyber security be looked upon like the government secret service, whereby this security was already embedded into the SMEs’ operations in protecting their data. The low adoption rates of using intelligent software amongst SMEs are studied in this investigation. The results revealed that SMEs have the appropriate cyber security packages in place but are not fully aware of their potential. Rawindaran et al. concluded that through government policies and processes, SMEs could minimize cyber threats. Funding opportunities in the form of grants, subsidies, and financial assistance were equally important, through various public sector policies and training.

Wylde, V. (2021) et al. in their paper [

34] also identified key challenges brought on by SMEs to bridge the knowledge-gap of organizations, businesses, government institutions, and their approach to using intelligent technology. The challenges indicated focused on the impact of cyber security and data privacy. Wylde’s paper further explored data security management systems and legal frameworks under ISO27001 and the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). In research by Alharbi (2021) [

35], it was emphasized that SMEs represent a majority of enterprises globally and yet have some difficulties in understanding the cause of concern around the impact of cyber security threats, particularly on their businesses and the damage they could do to their assets. Alharbi’s research aimed to measure the effectiveness of security practices in SMEs in Saudi Arabia. A total of 282 SME respondents participated from Saudi Arabia and multiple regression tests were conducted on the results to analyze the effectiveness of 12 cyber security practices in relation to three aspects: financial damage, loss of sensitive data, and restoration time within the SME business. The findings indicated that having an inspection team and a recovery plan may help limit the financial damage caused by cyber security attacks on these SMEs. The results also show that cyber security awareness, knowledge of cyber security damage, and professionals’ salaries were related to the loss of sensitive data. In conclusion, the results indicated that contact with cyber security authorities such as the NCA and having an inspection team were statistically significant and had an impact on restoration time.

A paper by Alzubaidi, A. (2021) in [

2] further substantiated this notion of cyber awareness through another survey questionnaire focusing on the number of people connected to and utilizing the internet. Alzubaidi’s paper highlighted concerns of how internet connections have introduced severe security risks and valuable information such as passwords, financial accounts, and other confidential data are considered attractive targets for attackers to be easily stolen through criminal activity. Cyber-attacks against this infrastructure can not only lead to data leakage but can also have significant financial implications and even lead to loss of life. Alzubaidi’s paper discussed the consequence of being able to defend against such attacks and how employees have a key role in these technologies, thus making awareness an important structure in our daily habits. The question here was related to trying to get end-users to understand the security mindset of the attacker and the potential risks of using the internet without care or caution of its potential impact on the loss of data and how it is a criminal playground. A security mindset refers to a way of thinking and approaching situations with a focus on maintaining security and preventing potential threats or attacks. It involves being aware of potential risks and vulnerabilities and taking proactive measures to mitigate them. A person with a security mindset is constantly assessing their surroundings and taking steps to protect themselves, their assets, and their organization from harm. This includes following best practices for password management, data encryption, and network security, as well as staying up to date on the latest security threats and vulnerabilities. In addition to technical knowledge and skills, a security mindset also involves a certain level of skepticism and caution. It involves questioning suspicious activity, scrutinizing requests for sensitive information, and being aware of social engineering tactics used by attackers to gain access to systems or information. Overall, a security mindset is essential for maintaining a safe and secure environment, whether it is in a personal or professional context. Alzubaidi’s paper focused on an online questionnaire with 1230 participants, with the results showing that 31.7% used public Wi-Fi to access the internet, 51% used their personal information to create their passwords, 32.5% did not have any idea about phishing attacks, and 21.7% had been a victim of cybercrimes while only 29.2% of them reported the crime, which reflects their levels of awareness. Alzubaidi’s paper concluded by offering recommendations based on an analysis of the results to improve the level of awareness. Albaroodi et al. [

36] examined the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in Open-Source Cloud Computing (OSCC) in Iraq. A sample of 385 respondents were surveyed over a period of five months. The results documented positive relationships between the perception and attitude of OSCC, between the perception and goals of OSCC, and between attitude and goals, and finally found that the adoption of OSCC had a positive effect on the relation between perception and intention.

Another concept that has also surfaced to investigate the behavior of SMEs is the Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible (BANI) environments, also known as the BANI framework [

37]. It offers a valuable lens to understand the challenges faced by SMEs operating in complex and rapidly changing landscapes, particularly within the context of cyber security governance and policy implementation.

The behavior of SMEs in BANI environments is highly relevant to this study as it sheds light on the unique dynamics and uncertainties faced by SMEs in the Industry 5.0 era. The BANI framework encompasses four key dimensions that capture the characteristics of such environments. According to Ghosh (2023), the BANI framework helps in understanding the challenges of organizations operating in complex and uncertain environments [

38]. SMEs, in particular, face the brittleness and vulnerability of their operating environments [

39]. The evolving cyber threats and rapidly changing technologies in Industry 5.0 have contributed to the brittleness of SMEs’ cyber security landscape [

40]. The prevalence of anxiety among SMEs in the face of cyber threats has been recognized. SMEs often lack resources and expertise in cyber security, leading to heightened anxiety; therefore, it is essential to explore the behavior of SMEs in relation to anxiety and identify strategies to address their concerns, such as improving awareness and fostering collaboration. The nonlinearity of BANI environments, characterized by interconnected cyber security risks, necessitates adaptive and agile responses from SMEs and shows the complexity of cause-and-effect relationships to effectively implement cyber security governance and policies. Understanding how SMEs navigate nonlinear environments can provide insights into their ability to adapt to emerging threats and implement effective cyber security measures [

41]. The incomprehensibility of BANI environments highlights the challenge faced by SMEs in comprehending cyber security risks and the evolving technological landscape that could lead to SMEs that may struggle to grasp the intricacies of cyber security, emphasizing the need for accessible guidance, educational resources, and support [

42]. Providing tailored resources and assistance can enhance SMEs’ cyber security capabilities and improve their understanding and implementation of governance and policy measures.

This literature review has certainly shown a pattern in Saudi Arabia’s and the UK’s SME landscape and the need for SMEs to further develop their own countries’ security aspects of their businesses to prevent themselves from getting hacked. With Saudi Arabia going through fast infrastructure changes in light of reaching its goal of Vision 2030, the cyber ecosystem is equally being challenged, with extensive data being produced. For the UK, the existing infrastructure of various aspects of governance and policy is cause for confusion in how SMEs can deal with and follow what is required and affordable in keeping their data safe. In light of this, governance and policymaking play an important role in ensuring that the checklist is complete for SMEs in both countries. This is so they can obtain the relevant training and education and instill new working behaviors in the workforce. This will then not only benefit their business but will contribute to how cyber security can protect their biggest commodity, their “data”.

4. Information Security Culture

Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom have different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds, which can affect their approach to information security. However, both countries recognize the importance of information security and have implemented measures to safeguard their digital assets. In Saudi Arabia, information security is a growing concern, and the government has taken steps to address it. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) has established a regulatory framework for information security in the banking sector. The government has also launched several initiatives to promote cyber security awareness and education, including the National Cybersecurity Authority and the Cybersecurity Innovation Program. In the United Kingdom, information security is a critical aspect of business operations. The government has established several regulatory bodies to oversee information security in various sectors, including the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The government has also developed a cyber security strategy and launched initiatives to promote awareness and education, such as Cyber Aware and the CyberFirst program. Overall, both Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom place significant importance on information security and have implemented measures to address the issue. However, there may be differences in their specific approaches and priorities based on their respective cultural and socio-economic contexts [

43].

Information security is also dependent on people, processes, and technology. Information security practices are governed by how people use and manage their technology, and how they follow practices and guidelines. These practices are met and understood based on the culture of the country and how its people react to it. This leads to the question of how culture creates an impact on how people perceive cyber risk and how they manage this risk accordingly within an SME organization. This scenario often tests their values and their decision-making capabilities within the boundaries of information security. Organizational information constantly shifts according to how much data is stored, processed, and transmitted. Information security cultures within countries often filter down to how people manage and run their businesses. Research has highlighted that establishing this culture can address behavioral issues [

40,

41]. An established information security culture can help reduce the dangers posed by employees carelessly mishandling data. Culture, according to the research of Alebaikan, R. (2023), states a link between particular behaviors and ways of “knowing, patterns of behaviour and meanings” that we learn as people “from or adopted within the groups to which people belong” [

43]. Culture is based on Hofstede’s five dimensions of “power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation”, and has been the most popular framework for understanding how different countries behave and the mindset they develop. Developing a cultural understanding between Saudi Arabia and the UK is important, as this makes people and nations understand why we behave the way we do in the event of a cyber threat or breach of security. Following Hofstede’s framework, Saudi Arabian culture is characterized by “collectivism” and “high power distance”, while UK culture is characterized by “high individualism” and “low power distance”. The power distance dimension refers to “the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally”. The UK has a low power distance to explain that “it is a country that strongly believes that inequalities among people should be kept at a minimum”. By contrast, in large power distance cultures such as Saudi Arabia, everyone is said to have “a rightful place in a social hierarchy and as a result acceptance and giving of authority is something that comes naturally”. Zimmermann, V. and Renaud, K. (2019), expanded culture theory from “humans being the problem” to “humans being a solution” in the introduction to the security mindset in their research. A cyber security mindset change also requires people to focus on aspects of human behavior and realize that actual strength can be their greatest ally in cyber security. The change in the mindset and organizational culture is referred to as ‘Cybersecurity, Differently’; however, it cannot be accomplished overnight [

44,

45].

5. Data Comparisons of UK Research

This study compared the research from data published in Rawindaran et al.’s research [

46] through the methodology of a quantitative approach through a survey. In 2021, data were collected from 122 sampled respondents of SMEs residing in the UK. Qualtrics was also used to create the survey and distribute it [

47]. A convenience sample was used through social media platforms such as LinkedIn and Twitter. The research adopted social networking applications amongst SMEs to gain information required for the research. Sampling strategies were used to enable advertising of the research to spread through networking. Potential respondents who showed interest in the survey were directed to the survey platform to read the information about the purpose of the research and the background of the research team. Rawindaran et al.’s survey question was based on the six hypothesis-testing questions in

Table 3.

The questionnaire focused on collecting information on respondents’ roles and personal information such as age range, identity, and their role, education, professional certifications, and industry. Each question was then compared to a question on SME awareness of the cyber security software package used within the business showing the participants’ cyber security awareness. Statistical analysis was used using the Chi-squared test to find the

p-values. Rawindaran et al.’s paper used

p-values to observe results based on two hypotheses, H0 and H1. A null hypothesis, H0, assumed that no difference or no effect of a treatment or an exposure fell on the question. Hypothesis H1 assumed that the null hypothesis was untrue. The questions asked in

Table 3 were used to verify the null/alternative hypotheses produced prior to the collection of results in the survey questionnaire.

Table 4 produced six null hypothesis and six alternative hypotheses based on the elements questioned in the survey.

Rawindaran et al. showed that if the

p-value is greater than 0.05, then the result is not statistically significant, as shown in

Table 5. A

p-value less than 0.05 (typically ≤0.05) was statistically significant. This means that the hypothesis is rejected and the alternative hypothesis is accepted. A

p-value higher than 0.05 (>0.05) is not statistically significant.

Using the

p-value measurement of significance, the elements were then compared in terms of the effects they had towards the research on being aware of intelligent software.

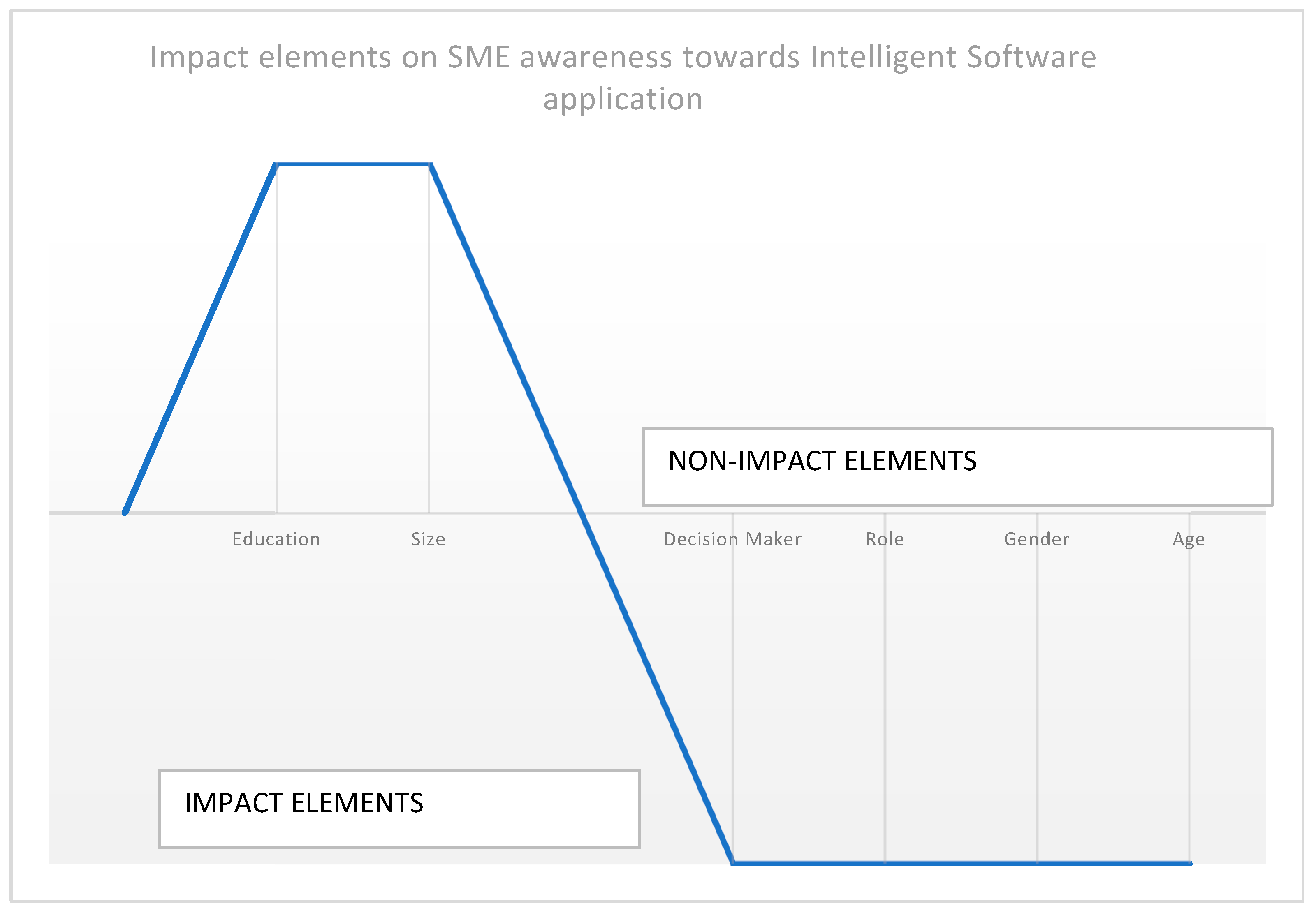

Figure 1 shows the six main elements that were measured: role, decision maker, size of the SME, gender, age, and education of the participants surveyed within the SME pool.

From this data extract, the results concluded that two elements had a significant impact on how awareness of intelligent software can be raised within an SME environment and its structure. These elements were education and the size of the SMEs. Elements that had no relationship to this hypothesis were the participant’s role within the SME business and if they were decision makers or not. Gender and age also showed no impactful relationship in raising awareness of cyber security within the SME business. Rawindaran et al.’s data showed that having the right educated people in place within the SMEs made the relationship of awareness to intelligent software packages more effective in protecting their data and gave their business a more informed choice within the SME.

This research will focus on the perceptions of Saudi Arabia’s SME culture and security mindset and aims to explain their resistance, if any, towards installing cyber security within their business with the governance and policy aligned to the ECC document and the NCA supporting the cause. It will also discuss their willingness (or not) to comply with aspects of governance, outlaid by the government, such as the ECC document. A comparison will also be made through the discovery of SMEs in the UK and the security mindset and culture that follow it. The next section explores the methodology and experiment conducted for this research.

6. Methodology

The research adopted a mixed-methods approach, combining both primary and secondary data collection methods to gather and analyze the necessary information. The selection of these methods was driven by the research’s scope, aims, and objectives. For primary data collection, a survey questionnaire was developed to specifically target the Saudi Arabian SME landscape. The questionnaire underwent a rigorous peer review process to ensure its sensitivity and applicability to SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Adjustments were made to tailor the questions to suit the research objectives. The survey was administered using the Qualtrics platform, which facilitated data collection and analysis. Respondents were provided with a face-to-face interview-style narration of the questions to ensure clarity and facilitate their understanding and response. Utilizing Qualtrics as a tool offered valuable capabilities in bridging knowledge gaps through effective data collection and analysis methods.

In addition to primary data, the research incorporated secondary data from an extensive literature review. Various published sources, such as books, government publications, newspapers, magazines, and journals, were carefully examined to gather factual information relevant to the research scope. Acquiring secondary data that directly aligned with the research objectives posed certain challenges. Nevertheless, the combination of primary data from the survey and the insights gained from the secondary resources added credibility and validity to the research.

By employing a combination of primary and secondary data collection methods, the research aimed to generate new knowledge and insights that contribute to the existing literature. The primary data collection involved surveying SME business owners and senior management personnel with SME knowledge in Saudi Arabia. On the other hand, the secondary data analysis involved comparing and contrasting previous publications and incorporating data from the UK respondents. This comprehensive approach allowed for a robust analysis, enabling the research to meet its objectives effectively.

The utilization of these research methodologies ensured a comprehensive exploration of the research topic, leading to a well-rounded analysis and enhancing the validity and credibility of the research findings. The combination of primary and secondary data collection methods provided valuable insights into the cyber security governance and policy landscape for SMEs in the context of Industry 5.0, contributing to the body of knowledge in this field.

6.1. Research Hypotheses

The following research hypotheses were formulated to investigate the relationships and differences in cyber security governance and policy implementation between Saudi Arabian SMEs and UK SMEs, as well as the impact of Industry 5.0 on these factors:

H1. There is a positive relationship between cyber security governance and policy implementation in Saudi Arabian SMEs. This hypothesis posits that SMEs in Saudi Arabia that have a robust cyber security governance framework and effectively implement cyber security policies will demonstrate higher levels of cyber security resilience and adherence to best practices.

H2. There is a positive relationship between cyber security governance and policy implementation in UK SMEs. This hypothesis suggests that SMEs in the UK with well-developed cyber security governance structures and effective policy implementation will exhibit higher levels of cyber security resilience and adherence to best practices.

H3. Industry 5.0 has an impact on cyber security governance and policy implementation in Saudi Arabian SMEs. This hypothesis explores the influence of Industry 5.0, which emphasizes the human aspect in production and personalized supply chains, on cyber security governance and policy implementation in Saudi Arabian SMEs. It suggests that the adoption of Industry 5.0 practices may impact the way cyber security governance is structured and policies are implemented.

H4. Industry 5.0 has an impact on cyber security governance and policy implementation in UK SMEs. This hypothesis investigates the influence of Industry 5.0 on cyber security governance and policy implementation in UK SMEs. It suggests that the adoption of Industry 5.0 practices may influence the cyber security governance structure and policy implementation approaches in UK SMEs.

H5. There are differences in cyber security governance and policy implementation between Saudi Arabian SMEs and UK SMEs. This hypothesis posits that there are significant variations in cyber security governance structures and policy implementation approaches between Saudi Arabian SMEs and UK SMEs. It suggests that cultural, regulatory, and contextual factors may contribute to these differences.

These hypotheses provide a framework for analyzing the relationships and differences in cyber security governance and policy implementation between Saudi Arabian SMEs and UK SMEs, as well as the impact of Industry 5.0 on these factors. The subsequent sections will present the findings and analysis to evaluate these hypotheses.

6.2. Primary Data: Saudi Arabia SME Methodology

The survey design and approach in this research followed current practices and drew inspiration from the Essential Cybersecurity Controls (ECC) document and its guidelines. The usability of the survey was evaluated across various devices, ensuring compatibility with mobile, desktop, and tablet platforms. To encourage a higher response rate, the survey was designed to be completed within 10 min. A total of 68 respondents provided accurate and complete responses, and their participation was voluntary and anonymous, in compliance with Saudi Arabia’s Data Protection Law. Informed consent was obtained from the respondents, and an ethics statement was included at the beginning of the survey. The research received approval from the Cardiff Metropolitan University ethics committee and had the support of King Abdulaziz University. The survey was conducted among members of the Saudi SME audience in both the English and Arabic languages. The questionnaire was initially written in English, with an Arabic translation provided below each question. Approximately 75% of the questions were conducted in Arabic, while the remaining 25% were in English. The survey covered various aspects, including general information, cyber security involvement, understanding of the ECC compliance document, and scenario-based questions related to risk. Participants were informed that the survey aimed to gather research data on the topic of cyber security awareness.

6.3. Secondary Data: United Kingdom (UK) SME Methodology

The data for this research were collected using a quantitative approach through a survey method, as described by Rawindaran et al. [

46]. The collected data were analyzed within the literature review section, and the results obtained were compared to the findings of Rawindaran et al.’s research. This served as a benchmark for the comparative analysis of the cyber security governance and policy landscape in Saudi Arabia.

7. Results

7.1. Saudi Arabia Results

7.1.1. Section One

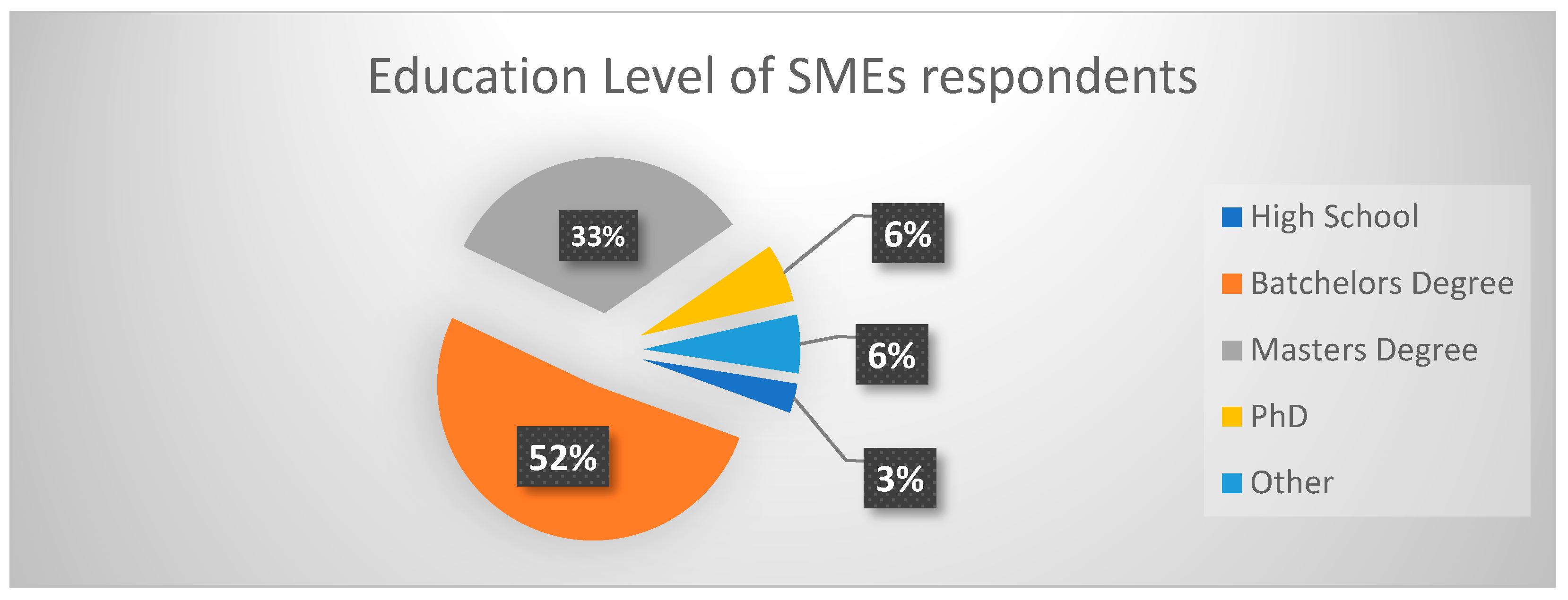

The research’s results and analysis are identified and analyzed in this section. The first section involved the gathering of information about the respondent’s background and business. The study asked demographic-style questions relating to educational background plus age, gender, role, and the industry of the SME respondent. The education level was divided into school education through university. The majority of the respondents sampled had a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree, as shown in

Figure 2.

The

Figure 2 results show that this combination was quite common in respondents running their business and employing trained people as part of the team. It was quite apparent that this sample of respondents was highly educated: 52% had a Bachelor’s degree, followed by 33% having a Master’s degree; 6% had a PhD. The category of ‘Other’ comprised respondents who had gone back to researching to improve on their business and commercial skills.

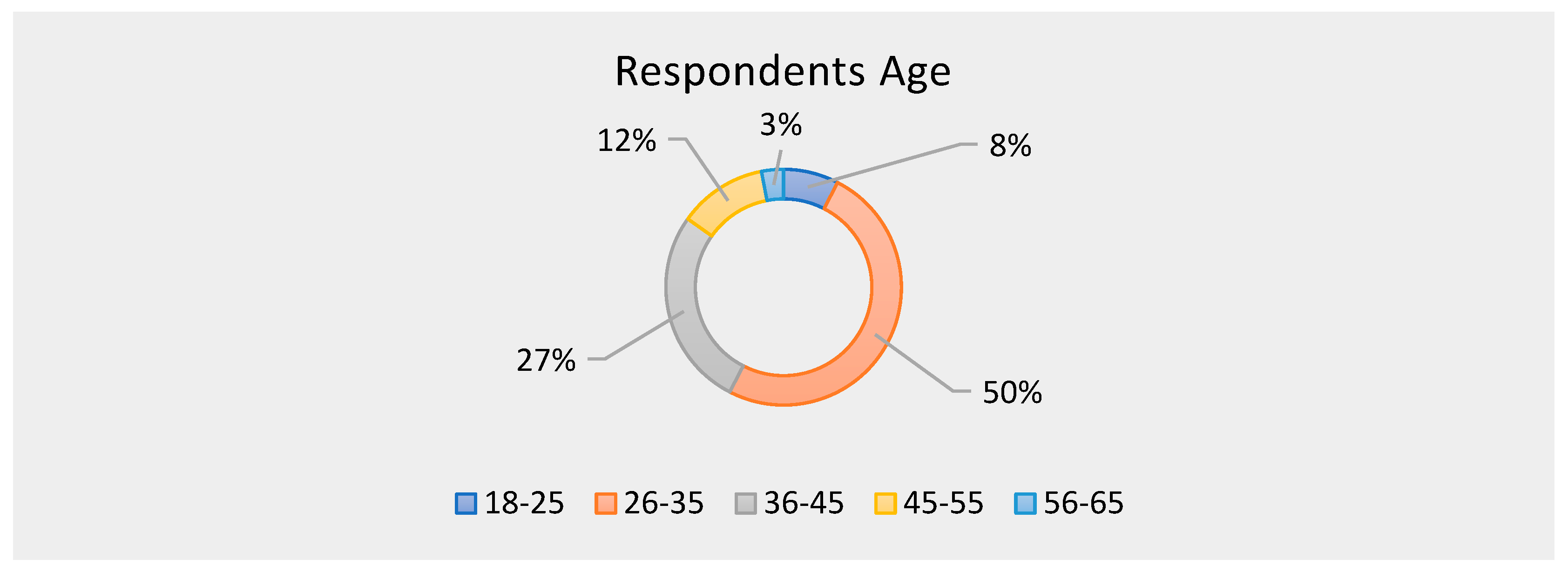

Figure 3 evaluates the age of the sampled respondents who participated in the research, with a large majority being between the ages of 26–35 years of age, at 50%, followed by 36–45, with 27%. Age categories such as 45–55 were at 12%, followed by 18–25 at 8% and 56–65 at 3%.

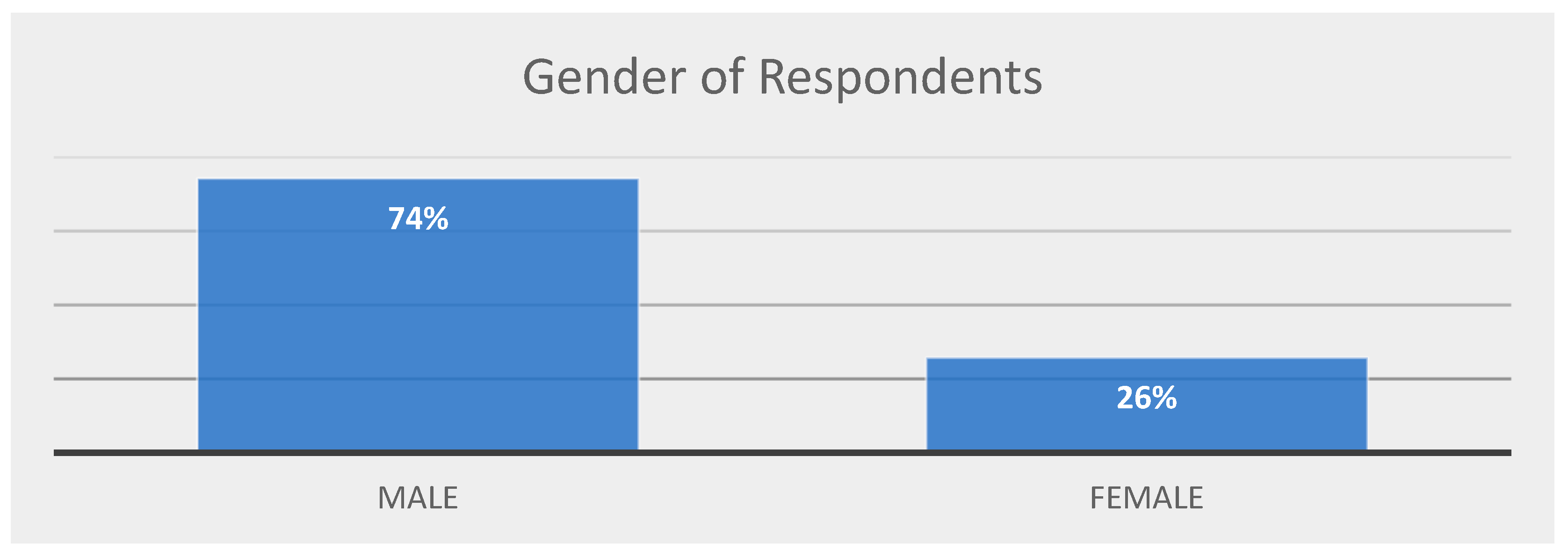

The majority of the survey was filled in by men, as shown in

Figure 4. The gender representation of respondents in the survey showed a 74% and 26% divide between male and female respondents.

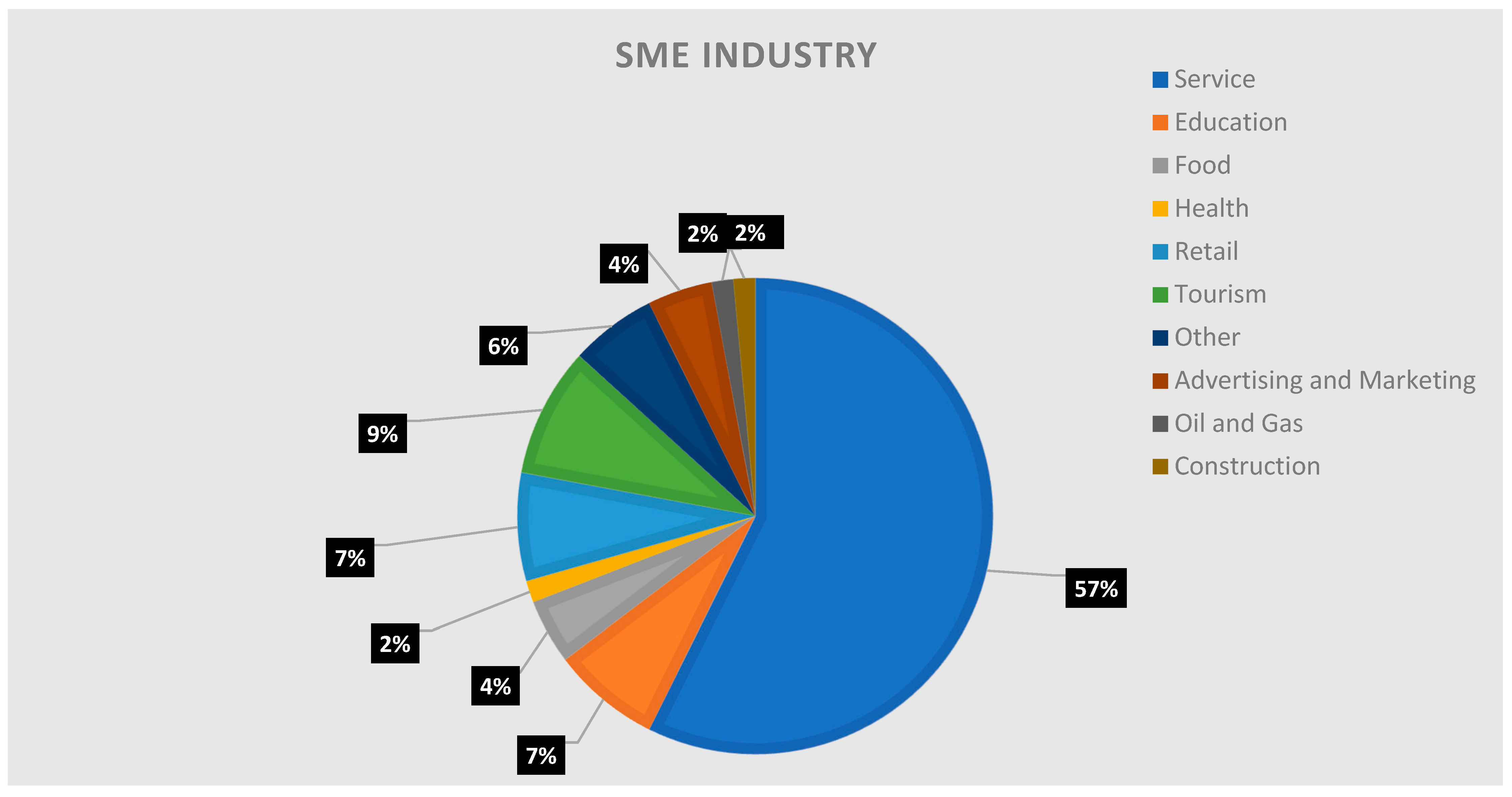

Figure 5 shows the data collected on the diverse types of SME industries.

Figure 5 shows that respondents were mostly represented by the service industry, at 57%, followed by tourism, education, and retail hovering between 7–10%. The rest covers industries such as construction, oil and gas, advertising and marketing, health, and food.

Figure 6 shows the role of the SME respondents’ participation, with 34% being business owners, 19% being CEOs, and 10–12% being managers, sales, and admin.

Section one showed a clear distribution of education level, age, gender, industry, and the roles of SME respondents. The identification of these elements is important in understanding the demographics and representation of the SMEs being surveyed in this research. To conclude Section one, 91% of the SME respondents had higher education and came from backgrounds of knowledge and education. With this in mind, the following results collected in the next sections could be contributing factors towards how the respondents reacted and answered.

7.1.2. Section Two

The second part of the survey asked respondents a series of questions relating to Monsha’at, the SME Authority of Saudi Arabia, the National Cyber Security Agency (NCA) in Saudi Arabia, and the ECC document and compliance towards it.

Table 6 shows how SMEs responded to these questions.

It was important to gauge and obtain an understanding of the awareness of Monsha’at and see the effects of the agency in giving SME businesses the support they need in keeping their businesses secure. Further detailed interpretations of the services used or not used by the SME respondents in this survey are shown in

Figure 7.

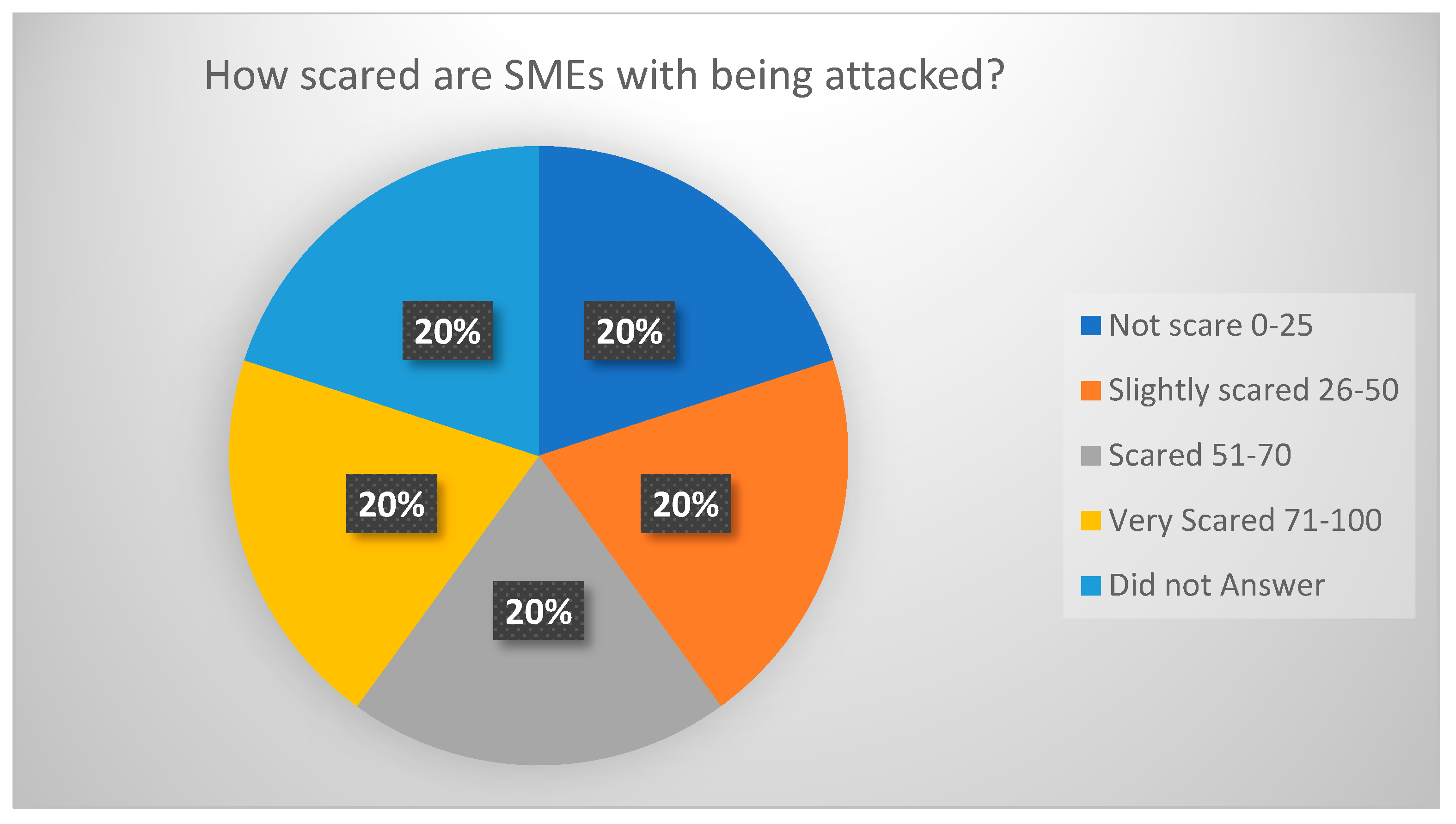

Of those participants that said they agreed to using the Monsha’at service, 66% claimed they were not sure what the service was or had ever used it. Between 9–10% of respondents used the Financial and Business support offered, and 6% used Monsha’at for training and receiving communications and sometimes to obtain business certifications. Only 3% used Monsha’at as IT support and used their consulting packages. Whilst Monsha’at offers a wide range of services and programs for businesses to tap into, the majority of respondents used the tip of the iceberg of the information provided by the organization. When asked how worried SMEs were about being attacked, the levels reported were equal across this level. The results here show an equal distribution of SME respondents at 20% showing that they were not scared, slightly scared, scared and very scared, as shown in

Figure 8, of being attacked online.

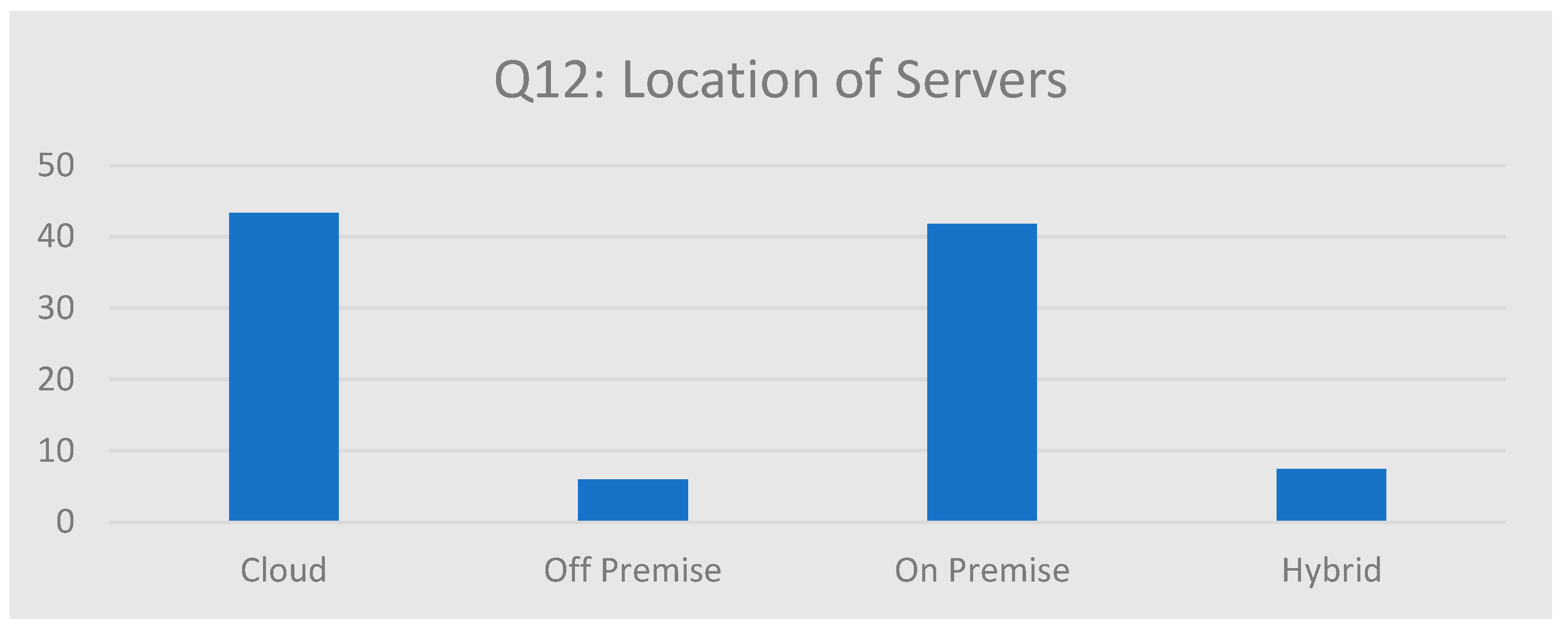

Figure 9 shows that the majority of SMEs used the Cloud option (43%) or On Premise (42%) as their server location. Some SMEs chose Off Premise and Hybrid, at 8% and 6%, respectively. The results here were mixed in that the security of the Cloud was catching on; however, a large number of SME respondents still were using an On Premises solution that was of high risk. Future research could potentially explore if the percentage of SMEs using Cloud will indeed increase or decrease, particularly due to the important decisions required regarding what security controls are essential and to be able to design the regulation and awareness campaign around these controls for the SMEs.

Table 6 asked SME respondents about their awareness of the National Cyber Security Agency (NCA) in Saudi Arabia. This result was quite relevant in that the government initiative was highly visible within Saudi Arabia and acknowledged its existence. The awareness of the NCA was then swiftly followed by the question of the ECC document and the SMEs’ compliance towards the document as a benchmark. This result was distributed 60/40, reaching a shift in awareness, and it could be increased, as a document like this should be one that all SMEs across Saudi Arabia are made aware of, seeing as it is a government initiative. For those that said YES, the breakdown of the compliance shows that 53% said that they would comply and 47% of SMEs said that they would not comply. For those who said that they would not comply, the reasonings were not captured but are something to consider for future works. As part of the ECC compliance, there were 12 questions asked in this section of the controls to show that SMEs were complying with the ECC document, and the answers are displayed in

Table 7 and

Figure 10.

Do you have any antivirus tools installed onsite on all computers?

Do you regularly update your software and operating systems on your computer?

Do you have security policies and governance practices in place such as BYOD, password policy, VPN, etc.?

Do you regularly perform risk assessments in your business?

Do you have a cyber security strategy?

Do you have a cyber security department that is not under the IT?

Do you consider security in your projects from the first day?

Do you perform vulnerability scanning?

Do you conduct regular auditing?

Do you have a security awareness program for your employees?

Do you perform regular backups?

Where are your servers located?

The ECC document was clear in its elements for SMEs and businesses to keep safe and secure throughout their usage of the internet and be safe from cyber-attacks. However, it was also clear that whilst half of the SMEs were complying, the other half did not have any measures in place. Ideally, the scenario would have been better if these SMEs showed a higher percentage in their compliance towards the ECC document, which could mean that further discussions towards this compliance might just increase the ECC awareness and usage.

7.1.3. Section Three

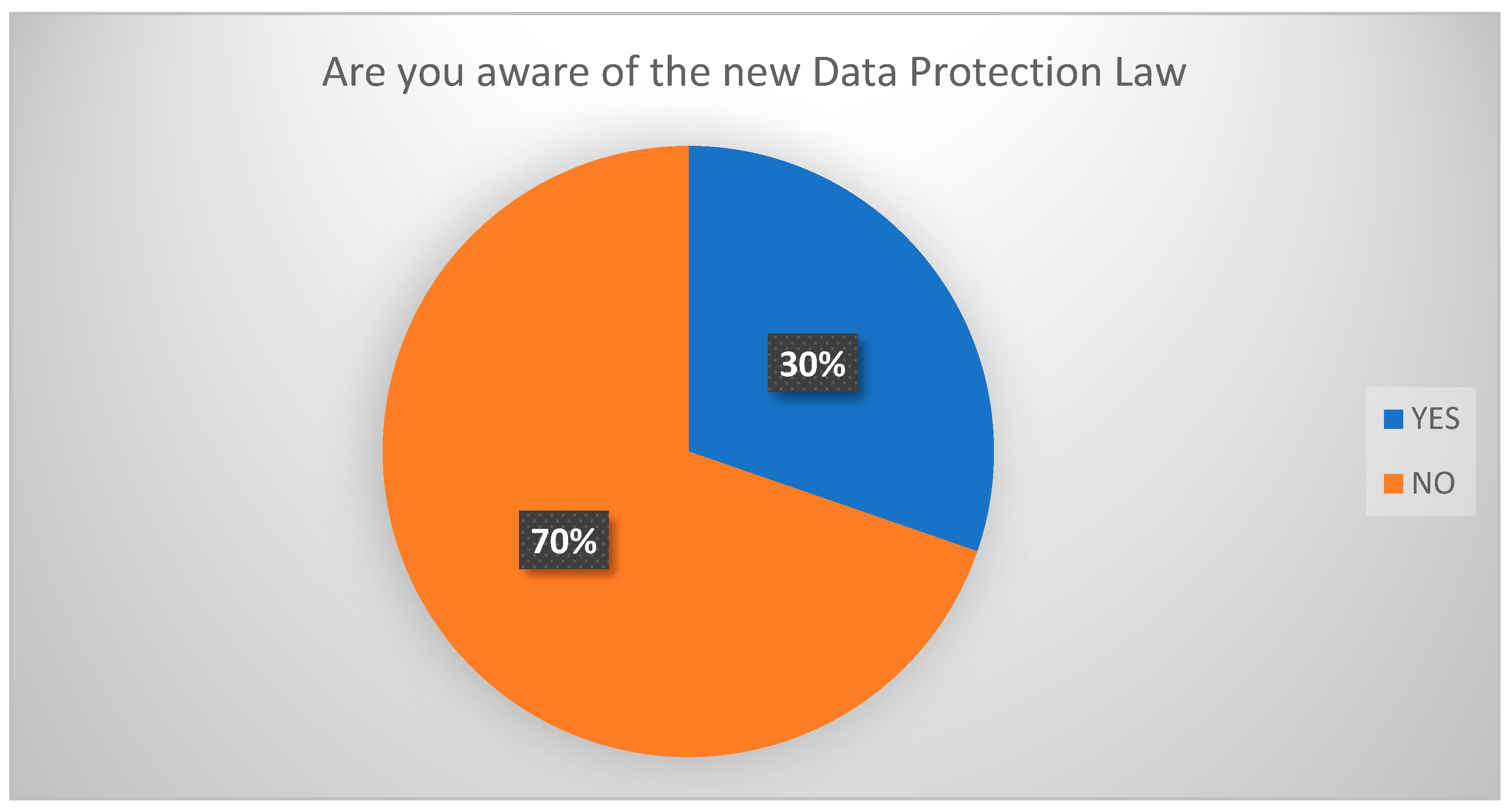

The third section of the survey asked SMEs about the new personal Data Protection Law and if they were aware of it being released in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 10 shows the distribution of SMEs answering the question, with 30% saying YES that they were aware and 70% saying that they were not aware.

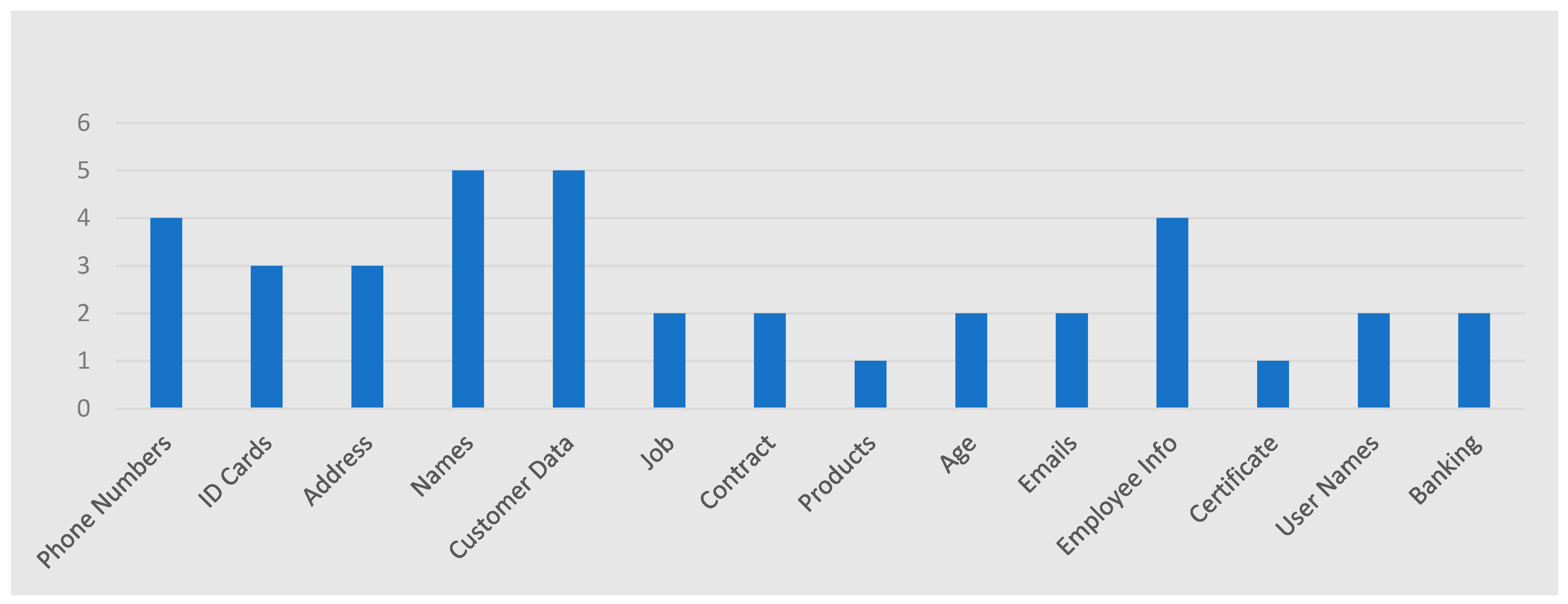

Of the 30% that said YES, the question asked the SME respondent what they considered to be personal data. The selection of answers showed a variety of responses from phone numbers, identification cards, address, names, and ages. Customer data, jobs, contract information, emails, and product information were also considered personal data from an employment point of view. Others included certifications, usernames, and banking information, as shown in

Figure 11.

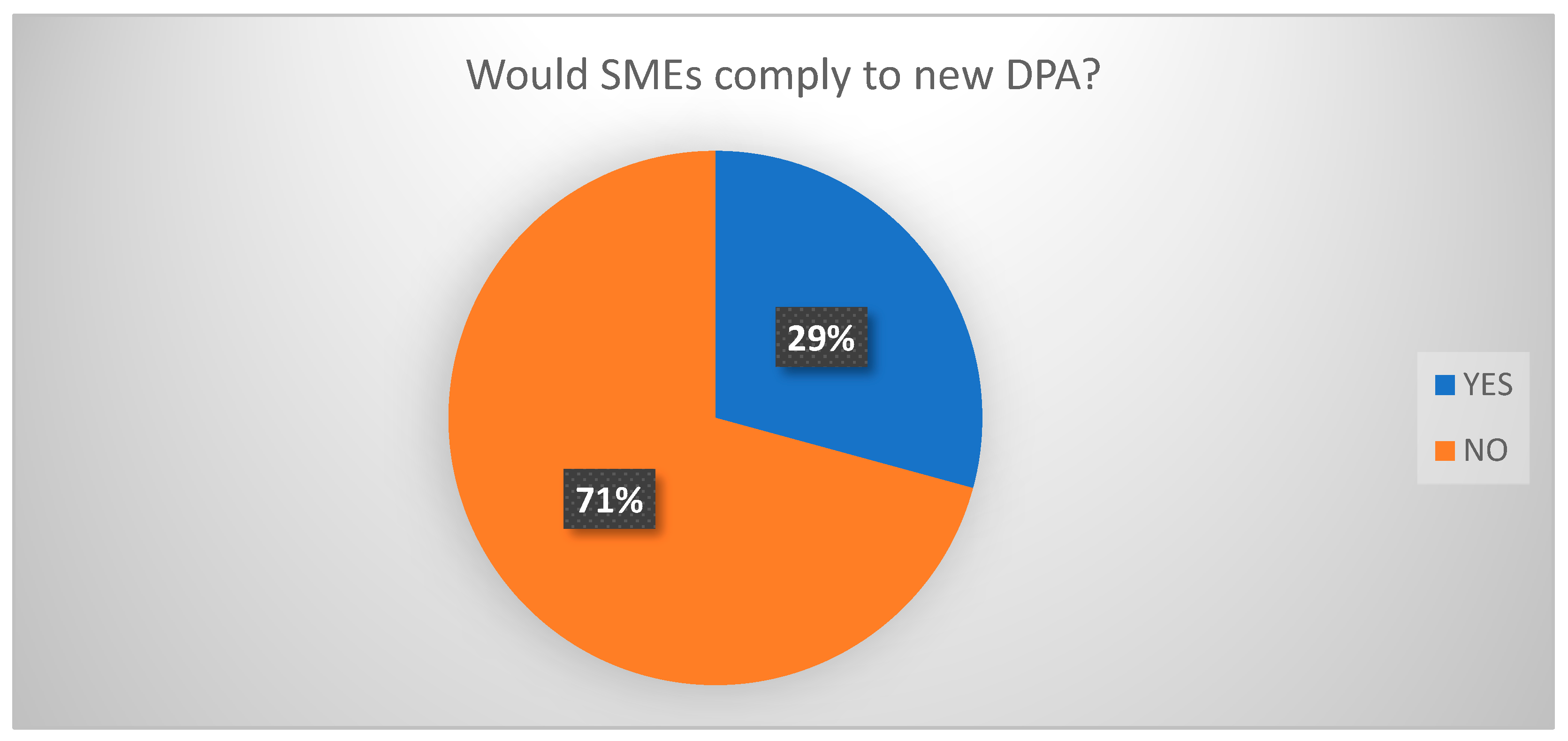

Figure 12 shows whether SMEs could comply with the new Data Protection Law. A total of 29% said they would whilst 71% were not sure of the impact of the Data Protection Law on their business.

7.1.4. Section Four

The last section of the survey asked two scenario-based questions to measure the risk element of security and the security mindset on SME businesses and how they would react in different situations. The first question asked was:

“If the SME has SAR 100,000 to spend, how much would they be willing to spend on security”.

Table 8 shows that 25% of SMEs would spend between 91–100% on security of the SAR100,000. This was followed by between 2–3% of SMEs spending 51–90% of the SAR100,000 on security. A total of 19% of SMEs would not spend anything on security and would rather not invest in cyber security, and 16% of the SMEs would only spend less than 10% of the money on security if they had the chance.

The second scenario-based question asked the SME: “A local florist running the business takes money by using the Point of Sale (POS) Cash Machine via card payments. On this day, the POS machine breaks, leaving cash taken from customers. In order to publicize this and to manage this expectation, the florists put a big poster on the shop window to say, ‘CASH ONLY’”. SMEs were then asked to identify the security risks attached to this scenario.

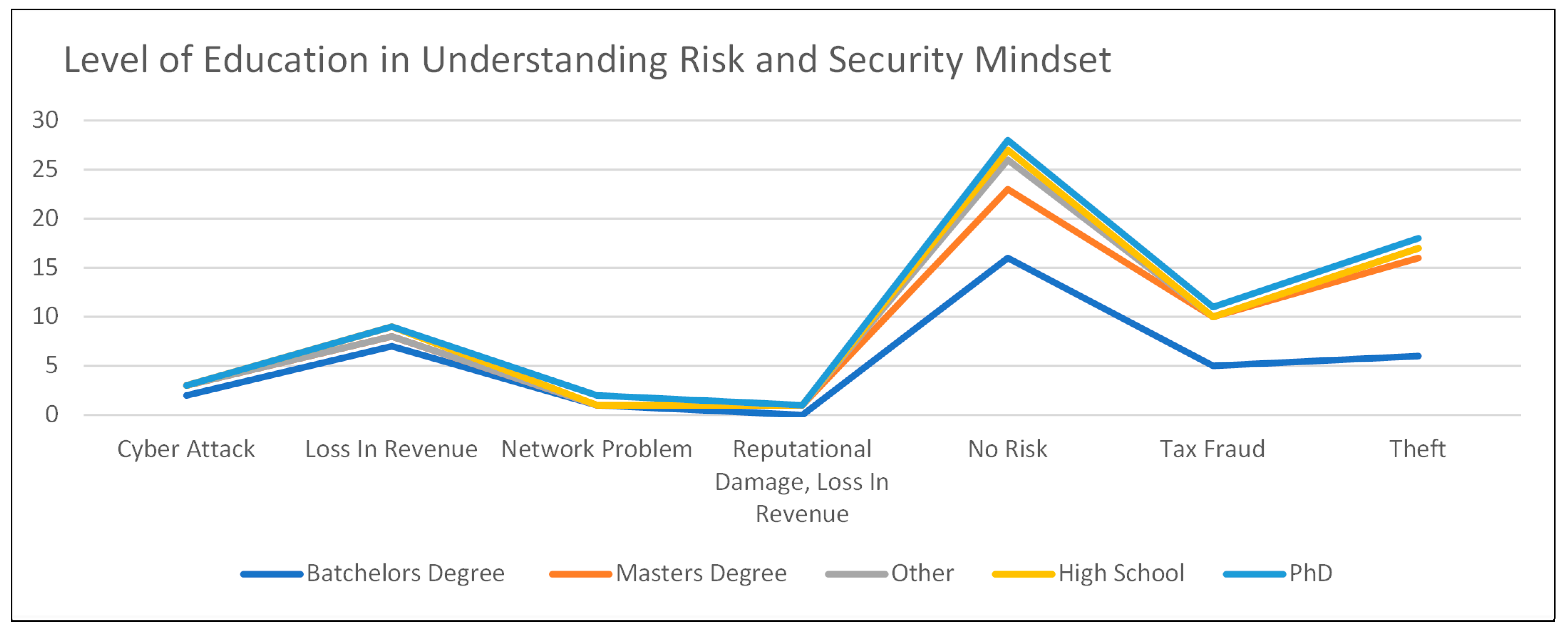

Table 9 shows the breakdown of answers linked to this second scenario and the further analysis associated with it. In sum, 28% of SMEs said that this scenario would not impose any security risk on the business, and 24% of the SMEs said that the broken POS machine could lead to potential theft for the business, as the florist would be collecting a large amount of cash on the day, thus exposing themselves to theft and burglary. In contrast, 15% of the SMEs directly stated that this scenario of the broken POS machine was an indication of tax fraud and 13% noted other attempts of fraud, whilst 13% said it would also lead to a loss in revenue. Only 5% mentioned the potential cyber-attack and hence the loss of the POS machine, with 3% stating that there is a network problem that the florist was waiting to be fixed, plus 2% stating that they would suffer some reputational damage in the process. This question was asked to measure the security mindset for future research in the area.

Scenario two was analyzed even further in that the understanding of the risk was compared to the level of education that was presented by the SMEs responding to the survey. As SME respondents took on further education, the understanding of risk and the security mindset increased accordingly. This was generally the case; however, outliers such as education levels of high school may have given the impression that these SME respondents might have stopped early in their education, only to understand risk earlier on in life’s challenges and scenarios outside the boundaries of education, as shown in

Figure 13.

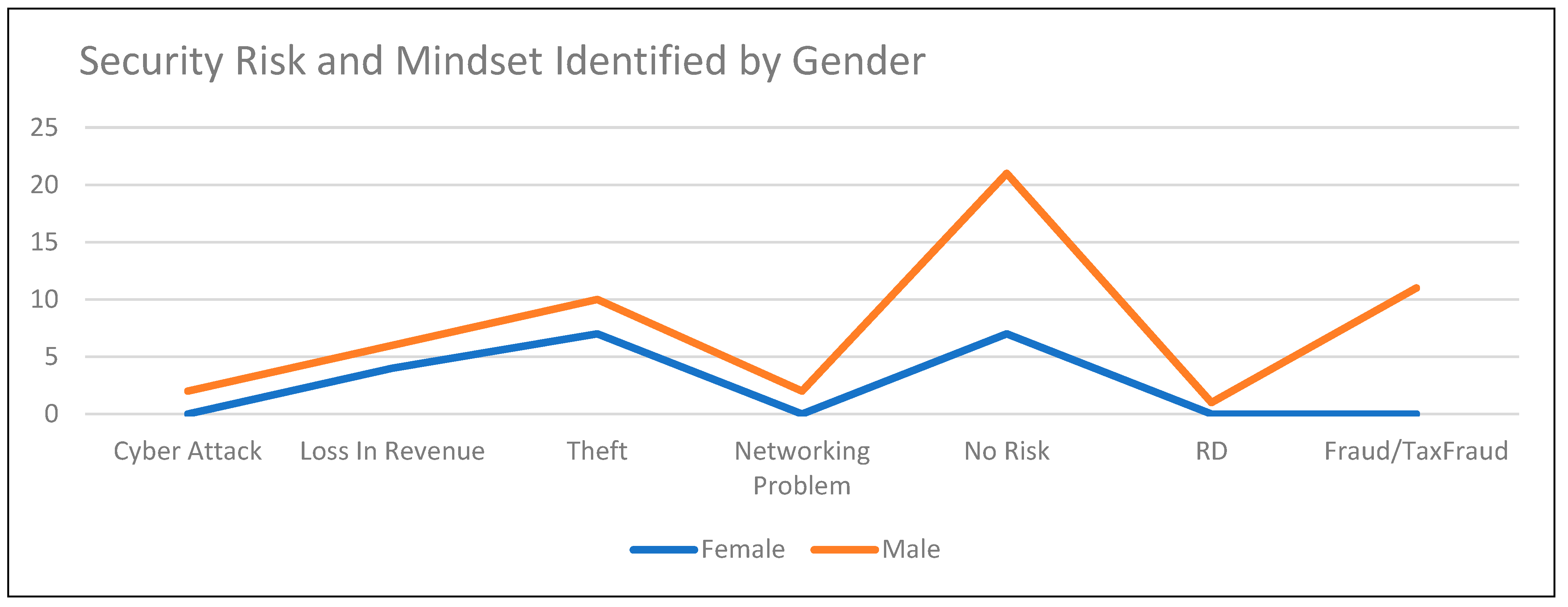

Figure 14 shows the security risk and mindset identified by gender to see how males and females react to risk and how they oversee or perceive different situations.

Most males in the SME respondents reacted to this scenario by assuming that what was happening in the shop was based on tax fraud and other fraudulent activities, whilst female respondents were more concerned that theft would be the main source of the risk and did not even consider fraud at any level. Males were more determined to state that there was no risk other than calculated risk, and females stated that there was a lower risk; however, they were unaware of the other consequences relating to this scenario.

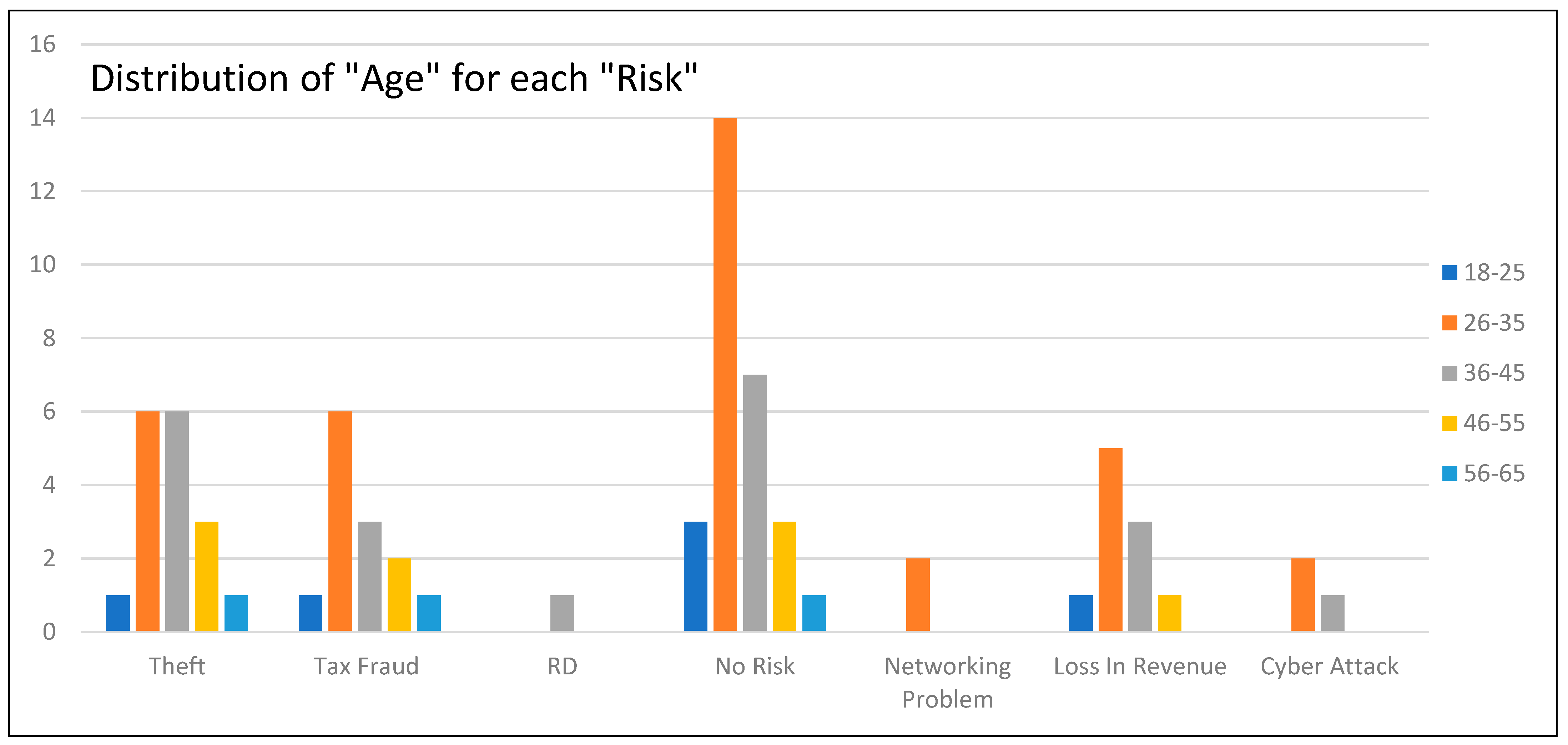

Figure 15 shows the distribution of age for each risk involved. Many who concluded that theft would be the risk were between the ages of 26–45, and they were equally concerned about tax fraud, fraudulent activities, loss of revenue, and cyber-attacks. The even younger age group of 26–35 was also of the notion that there was no risk involved. The age group of 46–55 was concerned about risk, theft, and fraud, whilst the group of 56–65 only stated that theft, tax fraud, and minimal risk were relevant based on the scenario. The youngest age group only considered theft, tax fraud, and loss of revenue to be the main risks to the business.

7.1.5. Further Analysis

This section explores how SMEs identified themselves and if they understood what size and category their business fell under when filling out this questionnaire.

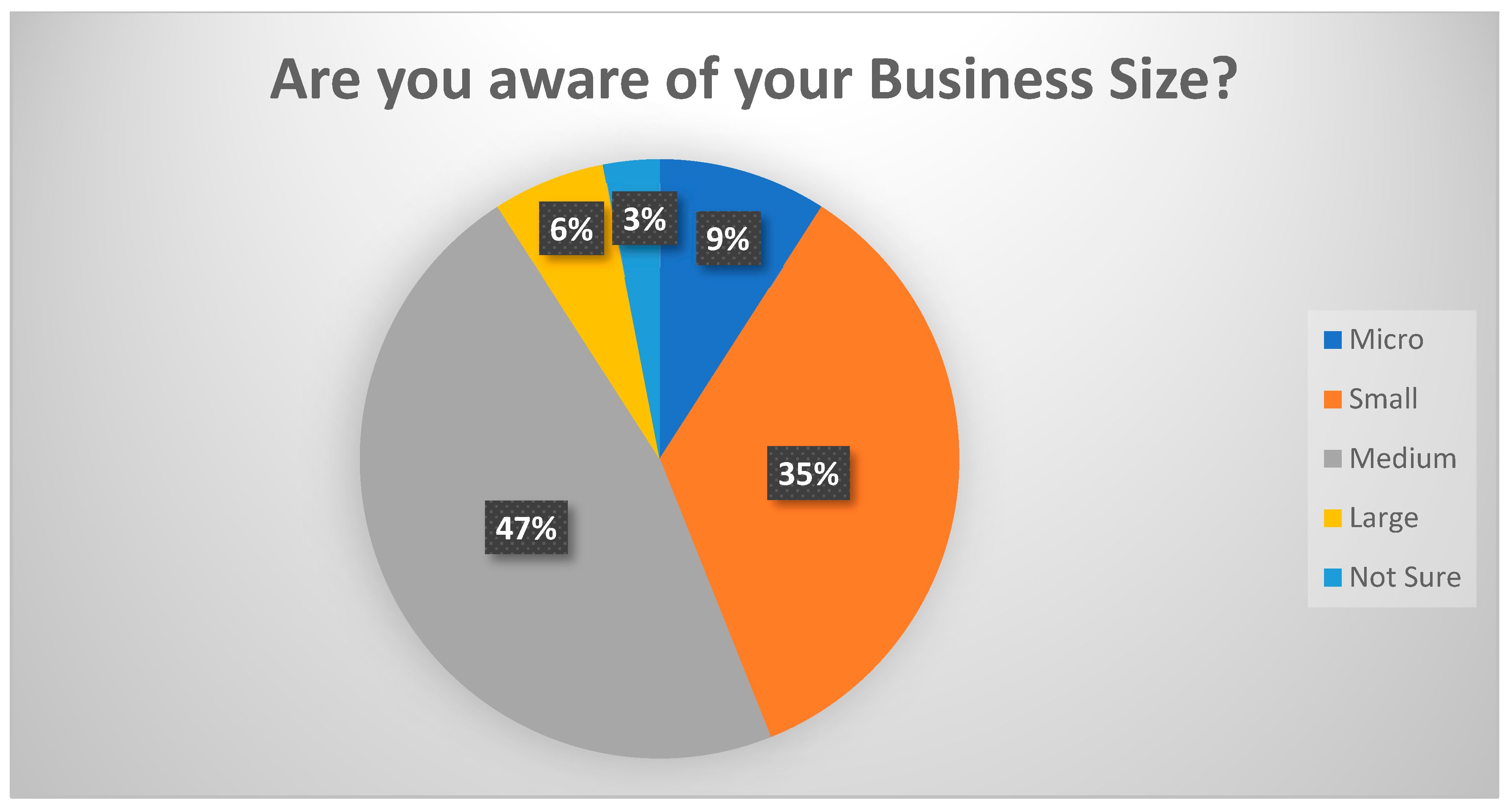

Figure 16 clearly shows that 47% recorded themselves as a medium enterprise, followed by 35% stating that they were small. In contrast, 9% identified themselves as micro, while 6% mentioned that they were large. Whilst they considered themselves large, their turnover fell under the category of SME, as mentioned in the criteria above. A total of 3% were not sure; this was alarming as they belonged to the SME category unknowingly, and this jumping to conclusions about being in this category could cause risk if not identified. This section also analyzed SMEs’ awareness towards the ECC document and how the controls affected how they kept their data safe and secure.

Figure 17 and

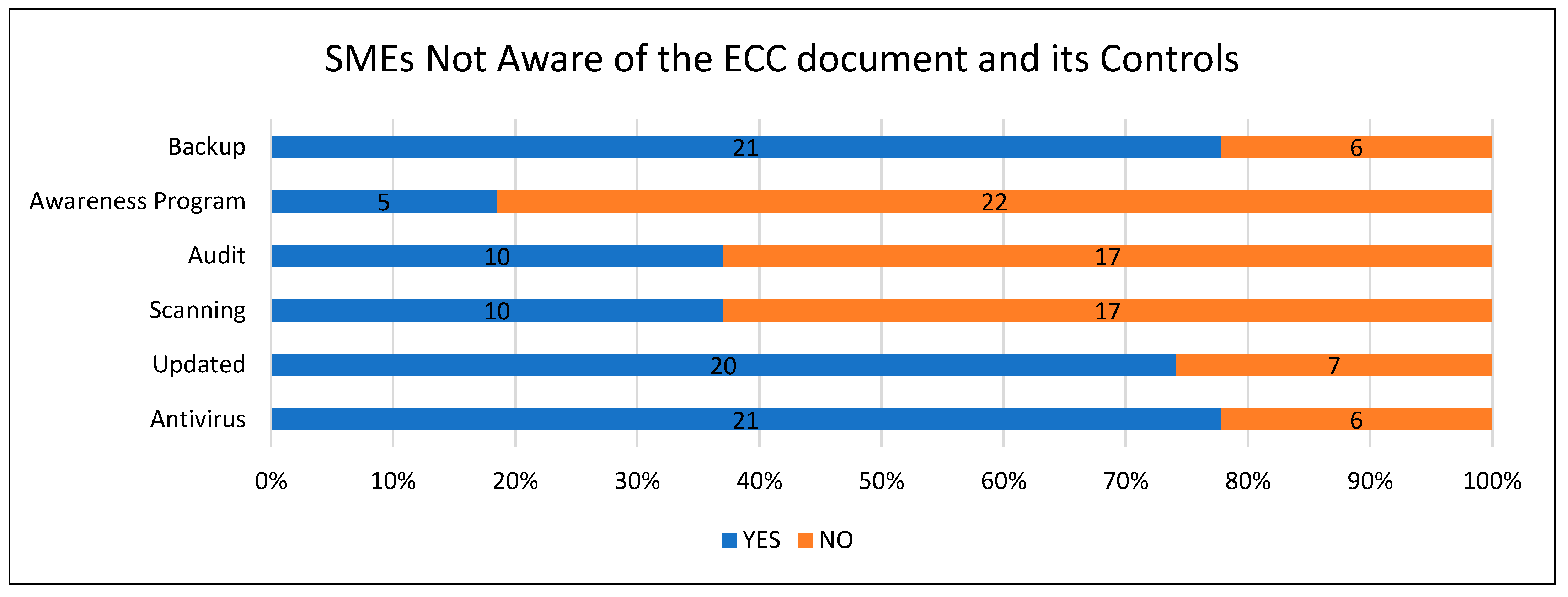

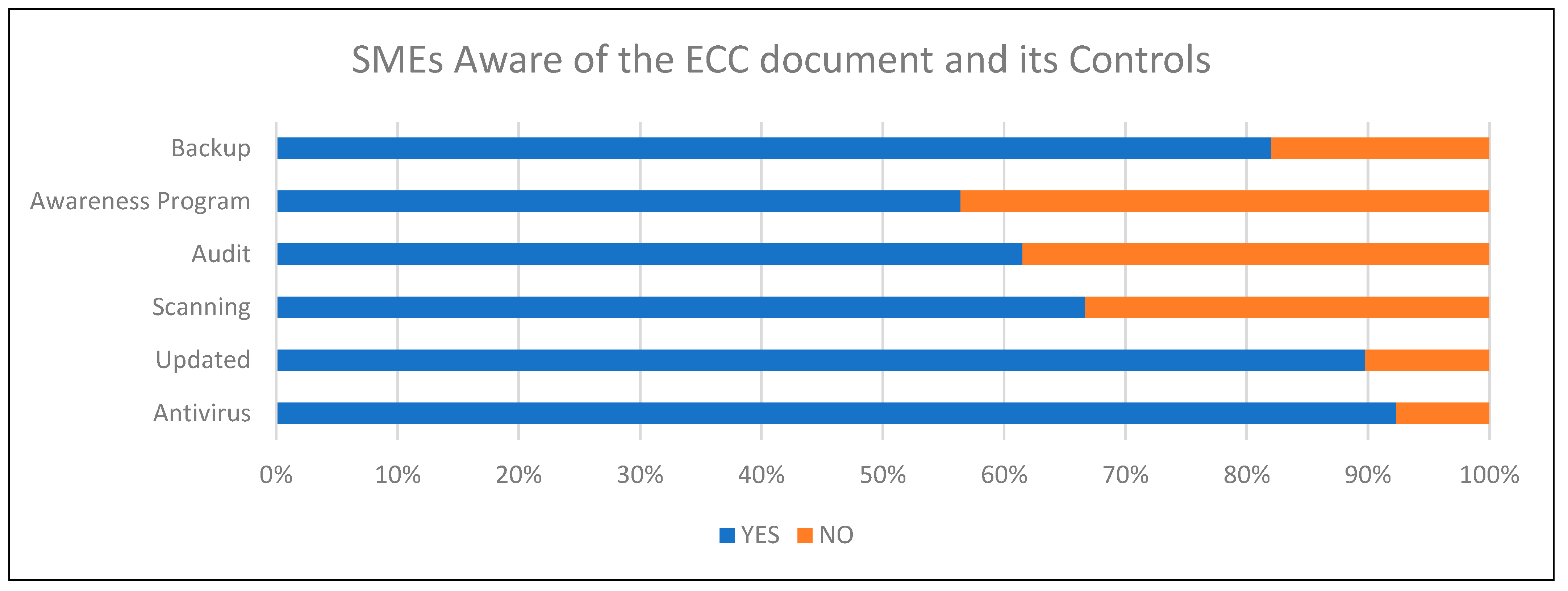

Figure 18 both show the results of if SMEs were aware of the controls and how it affected their answers towards the document content. Comparing both figures results in the conclusion that when SMEs were aware of the ECC and its controls, the percentage of SMEs conducting daily backups, running awareness programs within the business, running auditing and vulnerability scanning, running software updates, and having antivirus software in place increased.

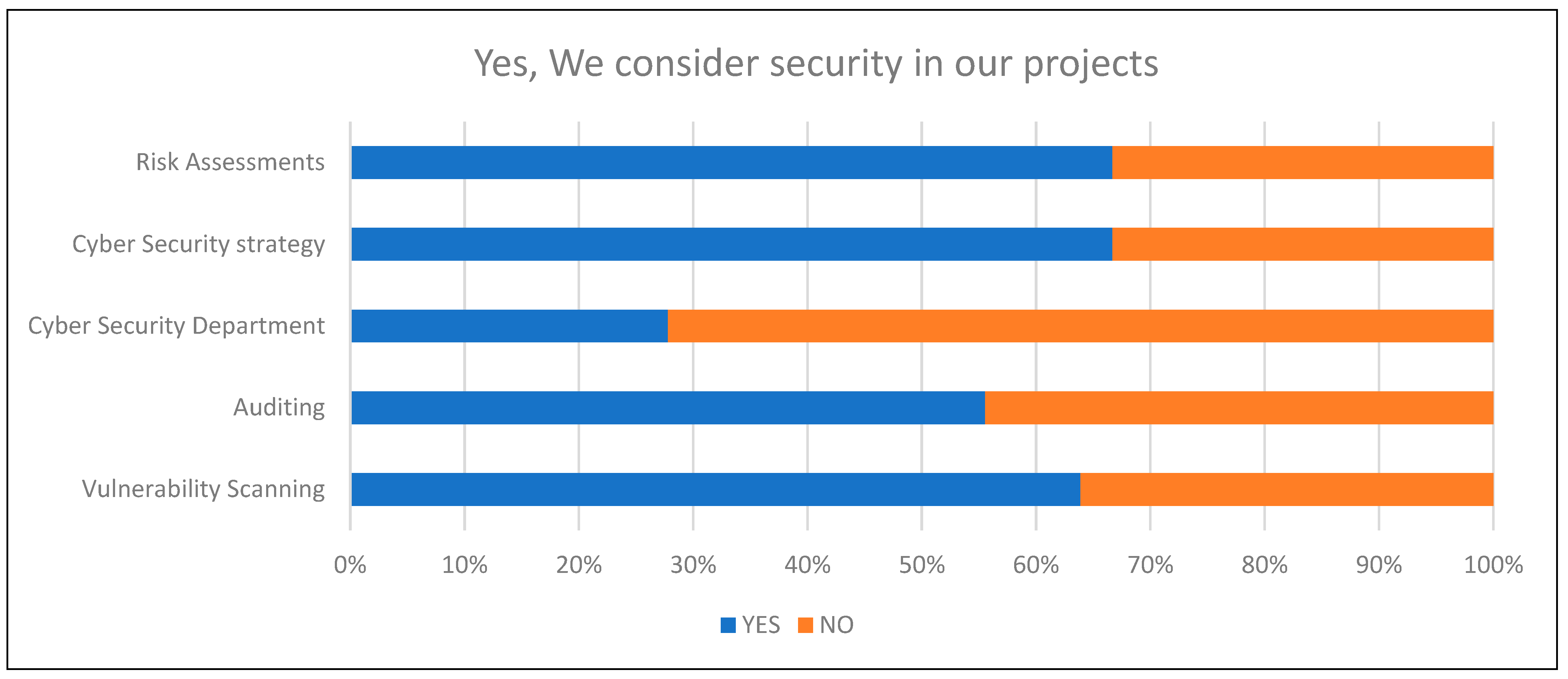

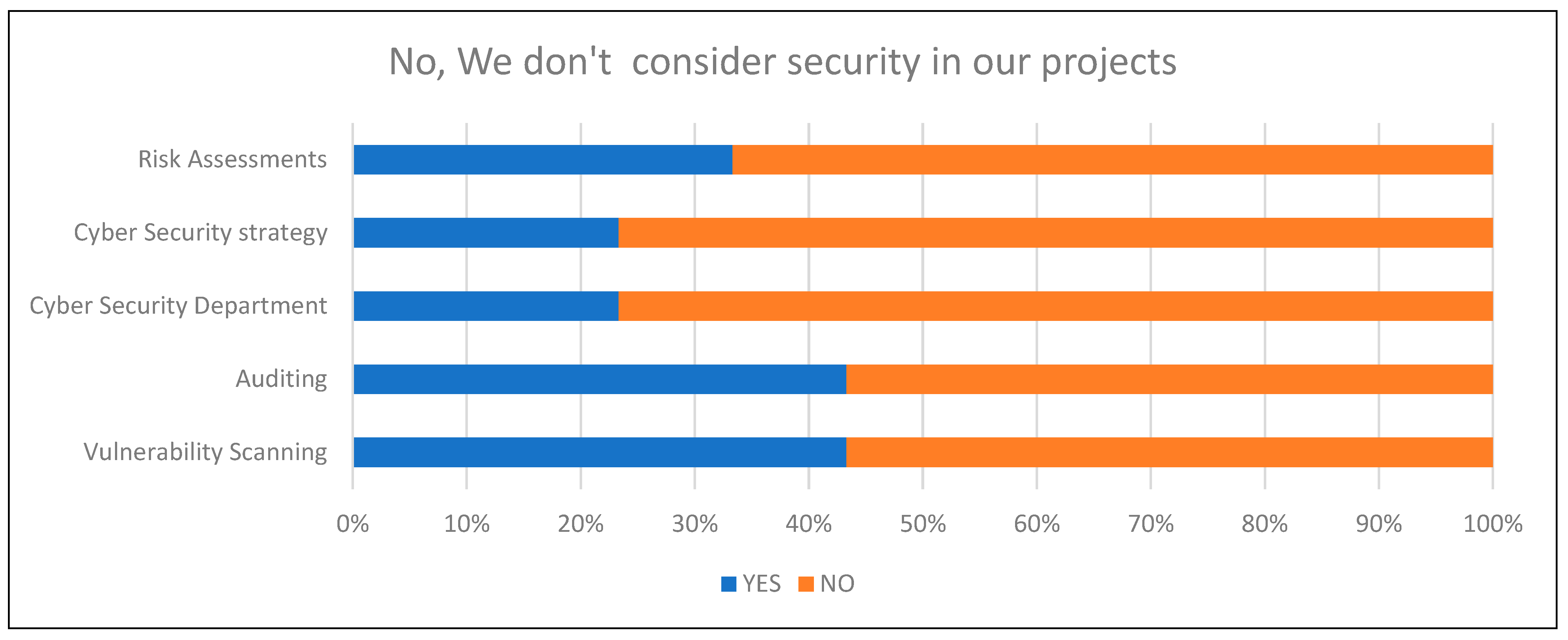

When considering if SMEs think about security within their projects on the first day, it was clear that the results showed that those that said Yes paid more attention to security overall.

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 show an increase in the SMEs performing auditing, having a Cyber Security Department in place, performing vulnerability scanning, and having a Cyber Security Strategy in place within the business.

Both figures show the difference between both results and the outcome of the variables and controls that reside within the ECC document.

8. Discussion

The research findings highlight the critical concern of cyber security for both the UK and Saudi Arabia, given their heavy reliance on technology within the context of Industry 5.0. A comparative study was conducted to examine the cyber security landscape in each country, revealing notable differences in their approaches.

The UK possesses a comprehensive set of cyber security laws and regulations, such as the Data Protection Act, the Computer Misuse Act, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Additionally, the UK has a national cyber security strategy and a dedicated cyber security center to monitor and respond to cyber threats. In contrast, Saudi Arabia is still in the process of developing a comprehensive cyber security framework and has limited cyber security laws and regulations. However, Saudi Arabia is actively making progress by establishing a national cyber security center and investing in cyber security technology and training programs.

The UK boasts a well-developed cyber security infrastructure, including advanced encryption technologies, firewalls, and intrusion detection systems. Moreover, the country has a well-trained cyber security workforce, supported by universities offering specialized cyber security courses. Saudi Arabia is also advancing its cyber security infrastructure and investing in technology and training programs to strengthen its cyber security capabilities.

Both the UK and Saudi Arabia face similar cyber security threats, such as ransomware attacks, phishing scams, and data breaches. However, Saudi Arabia, due to its geopolitical position in the Middle East, is also at risk of cyber-attacks from state-sponsored hackers. The UK has a strong track record of international cooperation on cyber security, collaborating closely with the EU and participating in various international cyber security forums and initiatives. Similarly, Saudi Arabia actively engages in international cyber security cooperation, contributing to global cyber security forums and initiatives.

In terms of enhancing cyber security resilience for SMEs, strengthening regulatory frameworks has a positive impact. As regulatory frameworks evolve to address emerging cyber threats and technological advancements, SMEs gain better resources to mitigate risks and protect their digital assets. Moreover, increasing awareness and education about cyber security among SMEs significantly contributes to their cyber security resilience. By providing SMEs with knowledge and practical guidance on cyber risks and best practices, awareness and education programs facilitate improved cyber security measures and incident response capabilities, as shown in

Figure 21.

Strong public–private partnerships also play a crucial role in influencing the cyber security resilience of SMEs. Collaboration between government entities, industry associations, and SMEs allows for the sharing of information, resources, and expertise, enabling SMEs to access critical cyber security support and guidance. The adoption of cyber security best practices is vital for enhancing cyber security resilience among SMEs. Implementing established standards, frameworks, and controls enables SMEs to better protect their systems and data, reducing their vulnerability to cyber threats. The regular monitoring and evaluation of cyber security governance and policy frameworks are essential components contributing to cyber security resilience. Ongoing assessment facilitates the identification of gaps, adaptation to evolving threats, and the refinement of existing measures, ensuring that policies and practices remain effective and up-to-date. Additionally, international collaboration positively impacts the cyber security resilience of SMEs. By engaging in knowledge sharing and collaborative initiatives with other countries, governments can develop harmonized cyber security standards and frameworks that benefit SMEs operating in a globalized industry landscape.

In conclusion, the research underscores the critical importance of cyber security for both the UK and Saudi Arabia, and the comparative study sheds light on their respective approaches and challenges. Strengthening regulatory frameworks, promoting awareness and education, fostering public–private partnerships, encouraging adoption of best practices, and ensuring continuous monitoring and evaluation are key future directions for enhancing cyber security governance and policy in Industry 5.0. By prioritizing these factors, policymakers, SMEs, and other stakeholders can collectively bolster cyber security resilience, safeguard SMEs from cyber threats, foster innovation, and contribute to the overall growth of the digital economy.

The understanding of the BANI framework with regard to the research findings adds a valuable perspective for understanding the behavior of SMEs in relation to cyber security governance and policy implementation in the context of Industry 5.0 and future works the comparative model could move towards. The BANI framework could provide insights into the challenges faced by SMEs operating in complex and rapidly changing environments, shedding light on their response mechanisms and resilience. The results could further evolve into the SMEs having categories in the BANI framework, offering a focus on the brittleness dimensions and emphasizing the fragility and vulnerability of SMEs, the anxious dimension that acknowledges the prevalence of anxiety among SMEs, the nonlinear aspect in recognizing the interconnected nature of cyber security risks, and the incomprehensibility dimension to highlight the challenges faced by SMEs in comprehending the intricacies of cyber security risks and the evolving technological landscape.

SMEs may struggle to grasp the complexities of cyber security, underscoring the importance of providing accessible guidance, educational resources, and support. By tailoring resources and assistance to SMEs’ specific needs, they can improve their understanding and implementation of governance and policy measures, enhancing their cyber security capabilities. This study recognizes the unique challenges and opportunities faced by SMEs in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom within the context of cyber security governance and policy. This holistic approach will contribute to the enhancement of cyber security resilience, promote a culture of awareness and collaboration, and foster economic growth in both countries within the Industry 5.0 landscape.

The discussion of the research findings strengthens the understanding of SME behavior in relation to cyber security governance and policy implementation. By acknowledging the challenges and dynamics within these frameworks, this study lays the foundation for future research and initiatives that can further enhance the cyber security resilience of SMEs operating in Industry 5.0.

9. Contribution to Research