Occupational Allergies in Dentistry: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Group of French Dentists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Recruitment

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Work Characteristics of the Study Respondents

3.2. Allergies

3.3. Occupation-Related Allergies

3.4. Factors Associated with the Occurrence of Occupational Allergies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johansson, S.G.O.; Bieber, T.; Dahl, R.; Friedmann, P.S.; Lanier, B.Q.; Lockey, R.F.; Motala, C.; Ortega Martell, J.A.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Ring, J.; et al. Revised Nomenclature for Allergy for Global Use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettis, E.; Assennato, G.; Ferrannini, A.; Tursi, A. Type I Allergy to Natural Rubber Latex and Type IV Allergy to Rubber Chemicals in Health Care Workers with Glove-Related Skin Symptoms. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2002, 32, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, L.; Cabral, R.; Gonçalo, M. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Caused by Acrylates and Methacrylates—A 7-Year Study. Contact Dermat. 2014, 71, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heratizadeh, A.; Werfel, T.; Schubert, S.; Geier, J. IVDK Contact Sensitization in Dental Technicians with Occupational Contact Dermatitis. Data of the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) 2001–2015. Contact Dermat. 2018, 78, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, C.P.; Depaola, L.G.; Rodgers, P.A. Occupation-Related Allergies in Dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2005, 136, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janas-Naze, A.; Osica, P. The Incidence of Lidocaine Allergy in Dentists: An Evaluation of 100 General Dental Practitioners. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2019, 32, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell, P.G.H.; Coombs, R.R.A. The Classification of Allergic Reactions Underlying Disease. In Clinical Aspects of Immunology; F. A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, T.V. The Gell–Coombs Classification of Hypersensitivity Reactions: A Re-Interpretation. Trends Immunol. 2003, 24, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.W.; Saunders, M.E.; Jett, B.D. (Eds.) Chapter 18—Immune Hypersensitivity. In Primer to the Immune Response, 2nd ed; Academic Cell: Burlington, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 487–516. ISBN 978-0-12-385245-8. [Google Scholar]

- Justiz Vaillant, A.A.; Zito, P.M. Immediate Hypersensitivity Reactions. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leggat, P.A.; Kedjarune, U.; Smith, D.R. Occupational Health Problems in Modern Dentistry: A Review. Ind. Health 2007, 45, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bârlean, L.; Dănilă, I.; Săveanu, I.; Balcoş, C. Occupational Health Problems among Dentists in Moldavian Region of Romania. Rev. Med. Chir. Soc. Med. Nat. Iasi. 2013, 117, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wallenhammar, L.M.; Ortengren, U.; Andreasson, H.; Barregård, L.; Björkner, B.; Karlsson, S.; Wrangsjö, K.; Meding, B. Contact Allergy and Hand Eczema in Swedish Dentists. Contact Dermat. 2000, 43, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowanadisai, S.; Kukiattrakoon, B.; Yapong, B.; Kedjarune, U.; Leggat, P.A. Occupational Health Problems of Dentists in Southern Thailand. Int. Dent. J. 2000, 50, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, N.A.; Thomson, W.M. Prevalence of Self-Reported Hand Dermatoses in New Zealand Dentists. N. Z. Dent. J. 2004, 100, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Leggat, P.A.; Smith, D.R. Prevalence of Hand Dermatoses Related to Latex Exposure amongst Dentists in Queensland, Australia. Int. Dent. J. 2006, 56, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, K.; Watanabe, T.; Diepgen, T.L. Self-Reported Hand Eczema among Dental Workers in Japan—A Cross-Sectional Study. Contact Dermat. 2016, 75, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voller, L.M.; Warshaw, E.M. Acrylates: New Sources and New Allergens. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 45, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawankar, R. Allergic Diseases and Asthma: A Global Public Health Concern and a Call to Action. World Allergy Organ. J. 2014, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawankar, R.; Holgate, S.; Canonica, G.; Lockey, R.; Blaiss, M. World Allergy Organization (WAO) White Book on Allergy; World Allergy Organisation: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). Tackling the Allergy Crisis in Europe—Concerted Policy Action Needed; EAACI: Zürich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aslami, R.A.; Elshamy, F.M.M.; Maamar, E.M.; Shannaq, A.Y.; Dallak, A.E.; Alroduni, A.A. Knowledge and Awareness towards Occupational Hazards and Preventive Measures among Students and Dentists in Jazan Dental College, Saudi Arabia. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arheiam, A.; Ingafou, M. Self-Reported Occupational Health Problems among Libyan Dentists. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2015, 16, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.N.; Aleem, S.A. Occupational Hazards among Dental Surgeons in Karachi. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. JCPSP 2016, 26, 320–322. [Google Scholar]

- Japundžić, I.; Novak, D.; Kuna, M.; Novak-Bilić, G.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Analysis of Dental Professionals’ and Dental Students’ Care for Their Skin. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2018, 52, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japundžić, I.; Vodanović, M.; Lugović-Mihić, L. An Analysis of Skin Prick Tests to Latex and Patch Tests to Rubber Additives and Other Causative Factors among Dental Professionals and Students with Contact Dermatoses. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 177, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japundžić, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Skin Reactions to Latex in Dental Professionals—First Croatian Data. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. JOSE 2019, 25, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, M.; Alanko, K.; Keskinen, H.; Kanerva, L. Dentist’s Occupational Asthma, Rhinoconjunctivitis, and Allergic Contact Dermatitis from Methacrylates. Allergy 2002, 57, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piirilä, P.; Hodgson, U.; Estlander, T.; Keskinen, H.; Saalo, A.; Voutilainen, R.; Kanerva, L. Occupational Respiratory Hypersensitivity in Dental Personnel. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 75, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puriene, A.; Aleksejuniene, J.; Petrauskiene, J.; Balciuniene, I.; Janulyte, V. Self-Reported Occupational Health Issues among Lithuanian Dentists. Ind. Health 2008, 46, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Ferček, I.; Duvančić, T.; Bulat, V.; Ježovita, J.; Novak-Bilić, G.; Šitum, M. Occupational Contact Dermatitis amongst Dentists and Dental Technicians. Acta Clin. Croat. 2016, 55, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Martinis, M.; Sirufo, M.M.; Ginaldi, L. Allergy and Aging: An Old/New Emerging Health Issue. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisesh, A.; Meyer, J.D.; Cherry, N.M. Prognosis and Work Absence Due to Occupational Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 2002, 46, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.; Gallagher, J.; Meaney, S. Quality of Life in Health Care Workers with Latex Allergy. Occup. Med. Oxf. Engl. 2010, 60, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savi, E.; Peveri, S.; Cavaliere, C.; Masieri, S.; Montagni, M. Laboratory Tests for Allergy Diagnosis. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frati, F.; Incorvaia, C.; Cavaliere, C.; Di Cara, G.; Marcucci, F.; Esposito, S.; Masieri, S. The Skin Prick Test. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Charous, B.L.; Blanco, C.; Tarlo, S.; Hamilton, R.G.; Baur, X.; Beezhold, D.; Sussman, G.; Yunginger, J.W. Natural Rubber Latex Allergy after 12 Years: Recommendations and Perspectives. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 109, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.J.; Sussman, G. Latex Allergy: Where Are We Now and How Did We Get There? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrangsjö, K.; Swartling, C.; Meding, B. Occupational Dermatitis in Dental Personnel: Contact Dermatitis with Special Reference to (Meth)Acrylates in 174 Patients. Contact Dermat. 2001, 45, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasson, H.; Boman, A.; Johnsson, S.; Karlsson, S.; Barregård, L. On Permeability of Methyl Methacrylate, 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Triethyleneglycol Dimethacrylate through Protective Gloves in Dentistry. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2003, 111, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, C.P.; Rodgers, P.A.; Sullivan, K.M. Occupational Allergens in Dentistry. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 4, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnerius, N.; Svedman, C.; Bergendorff, O.; Björk, J.; Bruze, M.; Engfeldt, M.; Pontén, A. Hand Eczema and Occupational Contact Allergies in Healthcare Workers with a Focus on Rubber Additives. Contact Dermat. 2018, 79, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepy, M.-N.; Lecuen, J.; Ratour-Bigot, C.; Stocks, J.; Bensefa-Colas, L. Accelerator-Free Gloves as Alternatives in Cases of Glove Allergy in Healthcare Workers. Contact Dermat. 2018, 78, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzi, F.M.; Katelaris, C.H.; Burke, T.V.; Widmer, R.P. Minimizing the Risks of Latex Allergy: The Effectiveness of Written Information. Aust. Dent. J. 2002, 47, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, R.J.; Persaud, Y.; Savliwala, M.N. Allergy Desensitization. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Incorvaia, C.; Ciprandi, G.; Nizi, M.C.; Makri, E.; Ridolo, E. Subcutaneous and Sublingual Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy: A Tale of Two Routes. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaar, O.; Bachert, C.; Bufe, A.; Buhl, R.; Ebner, C.; Eng, P.; Friedrichs, F.; Fuchs, T.; Hamelmann, E.; Hartwig-Bade, D.; et al. Guideline on Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy in IgE-Mediated Allergic Diseases. Allergo J. Int. 2014, 23, 282–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscato, G.; Pala, G.; Sastre, J. Specific Immunotherapy and Biological Treatments for Occupational Allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 14, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leynadier, F.; Herman, D.; Vervloet, D.; Andre, C. Specific Immunotherapy with a Standardized Latex Extract versus Placebo in Allergic Healthcare Workers. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 106, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, J.; Fernández-Nieto, M.; Rico, P.; Martín, S.; Barber, D.; Cuesta, J.; de las Heras, M.; Quirce, S. Specific Immunotherapy with a Standardized Latex Extract in Allergic Workers: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettis, E.; Colanardi, M.C.; Soccio, A.L.; Marcandrea, M.; Pinto, L.; Ferrannini, A.; Tursi, A.; Vacca, A. Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Latex-Induced Urticaria: A 12-Month Study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 156, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucera, E.; Mezzacappa, S.; Buonomo, A.; Centrone, M.; Rizzi, A.; Manicone, P.F.; Patriarca, G.; Aruanno, A.; Schiavino, D. Latex Immunotherapy: Evidence of Effectiveness. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. Dermatol. Alergol. 2018, 35, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastaminza, G.; Algorta, J.; Uriel, O.; Audicana, M.T.; Fernandez, E.; Sanz, M.L.; Muñoz, D. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Natural Rubber Latex Allergic Patients. Trials 2011, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, A.I.; Anda, M.; Bonifazi, F.; Bilò, M.B.; Leynadier, F.; Fuchs, T.; Ring, J.; Galvain, S.; André, C. Specific Immunotherapy with Standardized Latex Extract versus Placebo in Latex-Allergic Patients. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 141, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, S.K.; Lin, S.Y.; Toskala, E.; Orlandi, R.R.; Akdis, C.A.; Alt, J.A.; Azar, A.; Baroody, F.M.; Bachert, C.; Canonica, G.W.; et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Allergic Rhinitis: ICAR: Allergic Rhinitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 108–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, M.A.; Alves, B.; Jacobson, M.; Hurwitz, B.; Sheikh, A.; Durham, S. Allergen Injection Immunotherapy for Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, CD001936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosbaum, A.; Vocanson, M.; Rozieres, A.; Hennino, A.; Nicolas, J.-F. Allergic and Irritant Contact Dermatitis. Eur. J. Dermatol. EJD 2009, 19, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, M.C.; Ramalingam, M. Starch and Natural Rubber Allergen Interaction in the Production of Latex Gloves: A Hand-Held Aerosol. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 110, S15–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, J.; Santais, M.-C.; Levy, D.A.; Ruff, F.; Leynadier, F. Immunoadjuvant Properties of Glove Cornstarch Powder in Latex-Induced Hypersensitivity. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2003, 33, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordre National Des Chirurgiens-Dentistes (France). Cartographie et Données Publiques; Ordre National Des Chirurgiens-Dentistes: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| n (N = 584) | % of the Total Population | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 140 | 24 |

| Women | 444 | 76 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 280 | 47.9 |

| 30–39 | 160 | 27.4 |

| 40–49 | 69 | 11.8 |

| ≥50 | 75 | 12.8 |

| Time of Practice (years) | ||

| <10 | 376 | 64.4 |

| 10–19 | 102 | 17.5 |

| 20–29 | 63 | 10.8 |

| Allergies | n (N = 584) | % of Total Population |

| Yes | 294 | 50.3 |

| No | 290 | 49.7 |

| Triggering Allergens | n (N = 294) | % of Respondents with Allergies |

| Pollens (e.g., flowers, grasses, trees) | 159 | 54.1 |

| Mites | 103 | 35 |

| Contact allergens (e.g., nickel, cosmetic product, resins) | 97 | 33 |

| Animal dander | 83 | 28.2 |

| Food | 75 | 25.5 |

| Drugs | 70 | 23.8 |

| Professional allergens | 55 | 18.7 |

| Venom | 40 | 13.6 |

| Molds | 29 | 9.9 |

| Allergy to 2 different allergens | 81 | 27.6 |

| Allergy to 3 different allergens | 53 | 18 |

| Allergy to >3 different allergens | 71 | 24.1 |

| Clinical Manifestations | n (N = 294) | % of Respondents with Allergies |

| Dermatologic | 207 | 70.4 |

| Respiratory | 186 | 63.3 |

| Ophthalmologic | 111 | 37.8 |

| Digestive | 29 | 9.9 |

| Severe (i.e., angioedema, anaphylaxis) | 32 | 10.9 |

| 2 different clinical manifestations | 61 | 20.7 |

| 3 different clinical manifestations | 85 | 28.9 |

| >3 different clinical manifestations | 26 | 8.8 |

| Treatment | n (N = 294) | % of Respondents with Allergies |

| No treatment | 135 | 45.9 |

| Reliever medications only | 113 | 38.4 |

| Maintenance treatment only | 20 | 6.8 |

| Maintenance treatment and reliever medications | 32 | 10.9 |

| Occupational Allergies | n (N = 584) | % of Total Population |

| Yes | 78 | 13.4 |

| No | 506 | 86.6 |

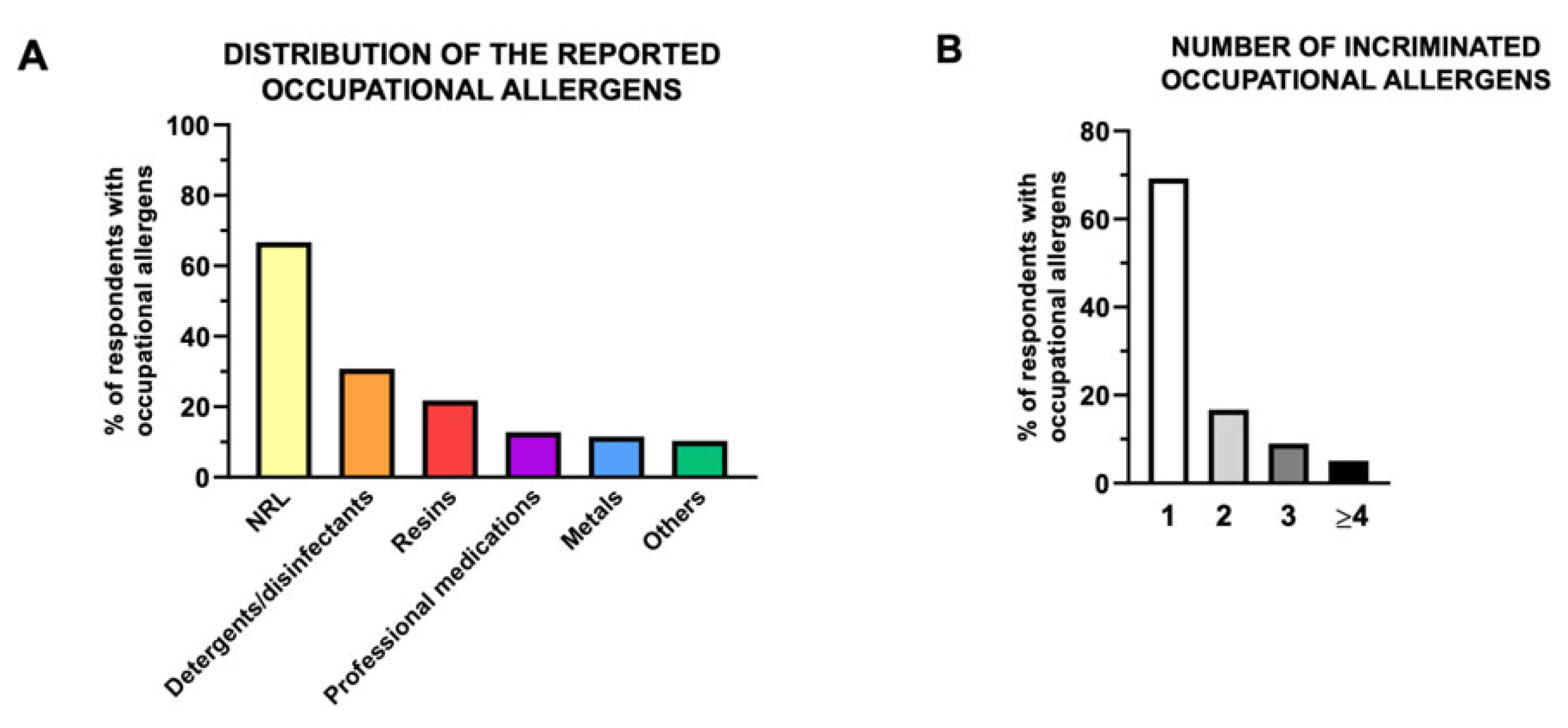

| Triggering Occupational Allergens | n (N = 78) | % of Respondents with Occupational Allergies |

| Natural rubber latex | 52 | 66.7 |

| Detergents/disinfectants | 24 | 30.8 |

| Resins | 17 | 21.8 |

| Professional medications (e.g., eugenol, sodium hypochlorite, sodium hydroxide) | 10 | 12.8 |

| Metals | 9 | 11.5 |

| Others (e.g., gloves powder) | 8 | 10.3 |

| 2 different occupational allergens | 13 | 16.7 |

| 3 different occupational allergens | 7 | 9 |

| >3 different occupational allergens | 4 | 5.1 |

| Work Stoppage Requirement | n (N = 78) | % of Respondents with Occupational Allergies |

| Not requirement | 70 | 89.7 |

| Temporary work cessation | 8 | 10.3 |

| Definitive work cessation | 0 | 0 |

| Maintenance Therapy | n (N = 78) | % of Respondents with Occupational Allergies |

| Yes | 27 | 34.6 |

| No | 51 | 65.4 |

| Antihistamines | 18 | 23.1 |

| Desensitization (i.e., allergen immunotherapy) | 6 | 7.7 |

| Homeopathy | 7 | 9.0 |

| Corticoids | 1 | 1.3 |

| >2 treatments | 4 | 5.1 |

| Reliever Medications | n (N = 78) | % of Respondents with Occupational Allergies |

| Yes | 50 | 64.1 |

| No | 28 | 35.9 |

| Oral antihistamines | 29 | 37.2 |

| Topical antihistamine (e.g., eye drops) | 6 | 7.7 |

| Topical corticosteroids (i.e., cream, ointment) | 28 | 35.9 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 9 | 11.5 |

| Nasal corticosteroids (i.e., spray) | 7 | 9.0 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (i.e., aerosol/spray) | 5 | 6.4 |

| Inhaled bronchodilators (i.e., aerosol/spray) | 7 | 9.0 |

| Combination of 2 medications | 18 | 23.1 |

| Combination of 3 medications | 8 | 10.3 |

| Combination of >3 medications | 3 | 3.8 |

| Improvement | n (N = 78) | % of Respondents with Occupational Allergies |

| Spontaneously | 15 | 19.2 |

| With maintenance therapy | 31 | 39.7 |

| With reliever medications | 31 | 39.7 |

| After remoteness from the work environment, no treatment required | 43 | 55.1 |

| After remoteness from the work environment and with treatment | 17 | 21.8 |

| Participants with Allergies | Participants with Occupational Allergies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of the Respective Groups | n | % of the Respective Groups | n | |||||

| Total population (N = 584) | 50.3 | 294 | 13.4 | 78 | ||||

| Descriptive Variables | % of the Respective Groups | n | OR (95%CI) | p-value | % of the Respective Groups | n | OR (95%CI) | p-value |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men (N = 140) | 47.9 | 67 | 11.4 | 16 | ||||

| Female (N = 444) | 51.1 | 227 | 1.14 (0.80–1.67) | NS | 14 | 62 | 1.26 (0.70–2.26) | NS |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <30 (N = 280) | 46.1 | 129 | 9.3 | 26 | ||||

| 30–39 (N = 160) | 56.3 | 90 | 1.50 (1.02–2.23) |  | 16.9 | 27 | 1.98 (1.11–3.54) |  |

| 40–49 (N = 69) | 53.6 | 37 | 1.35 (0.80–2.30) | 18.8 | 13 | 2.27 (1.08–4.69) | ||

| ≥50 (N = 75) | 50.7 | 38 | 1.20 (0.72–2.00) | 16 | 12 | 1.86 (0.89–3.89) | ||

| Time of practice (years) | ||||||||

| <10 (N = 376) | 48.9 | 184 | 12.2 | 46 | ||||

| 10–19 (N = 102) | 57.8 | 59 | 1.43 (0.92–2.23) |  | 15.7 | 16 | 1.33 (0.72–2.47) |  |

| 20–29 (N = 63) | 42.9 | 27 | 0.78 (0.46–1.34) | 17.5 | 11 | 1.52 (0.74–3.12) | ||

| ≥30 (N = 43) | 55.8 | 24 | 1.31 (0.70–2.49) | 11.6 | 5 | 0.94 (0.35–2.52) | ||

| Occupational Allergy (n) | No Occupational Allergy (n) | OR | 95%CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No general allergy (n) | 11 | 279 | |||

| General allergy (n) | 67 | 227 | 7.49 | 3.90–14.50 | *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boudinar, L.; Offner, D.; Jung, S. Occupational Allergies in Dentistry: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Group of French Dentists. Oral 2021, 1, 139-152. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1020014

Boudinar L, Offner D, Jung S. Occupational Allergies in Dentistry: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Group of French Dentists. Oral. 2021; 1(2):139-152. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1020014

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoudinar, Lise, Damien Offner, and Sophie Jung. 2021. "Occupational Allergies in Dentistry: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Group of French Dentists" Oral 1, no. 2: 139-152. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1020014

APA StyleBoudinar, L., Offner, D., & Jung, S. (2021). Occupational Allergies in Dentistry: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Group of French Dentists. Oral, 1(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral1020014