Health Literacy and Disease Knowledge in Adolescents and Young Adults with SCD in Benin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. SCD Knowledge

2.2.2. Health Literacy

2.2.3. Health Outcomes

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomson, A.M.; McHugh, T.A.; Oron, A.P.; Teply, C.; Lonberg, N.; Tella, V.V.; Wilner, L.B.; Fuller, K.; Hagins, H.; Aboagye, R.G.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence and Mortality Burden of Sickle Cell Disease, 2000–2021: A Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e585–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, G.J.; Piel, F.B.; Reid, C.D.; Gaston, M.H.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Krishnamurti, L.; Smith, W.R.; Panepinto, J.A.; Weatherall, D.J.; Costa, F.F.; et al. Sickle Cell Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2018, 4, 18010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghany, S.M.; Tabbakh, A.T.; Nur, K.I.; Abdelrahman, R.Y.; Etarji, S.M.; Almuzaini, B.Y. Analysis of Causes of Hospitalization Among Children with Sickle Cell Disease in a Group of Private Hospitals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Blood Med. 2021, 12, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, O.M.; Buhalim, R.A.; Al Jabr, F.A.; AlSaeed, M.N.; Al-Hajji, I.A.; Al Saleh, Y.A.; Buhalim, M.A.; Al Dehailan, A.M.; Al-Hajji, I.; Alsaleh, Y.A. Reasons for Hospitalization of Sickle Cell Disease Patients in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Single-Center Study. Cureus 2021, 13, e19299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U. Implications of climatic change on sickle cell anemia: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.G. The Role of Infection in the Pathogenesis of Vaso-Occlusive Crisis in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 3, e2011028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: A Challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Communication Strategies into the 21st Century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.L.; Carter, P.A.; Becker, H.A.; Garcia, A.A.; Mackert, M.; Johnson, K.E. Health Literacy in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 36, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.L. Health literacy in adolescents: An integrative review. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2014, 19, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauben, S.J.; Cavanaugh, K.L.; Fagerlin, A.; Ikizler, T.A.; Ricardo, A.C.; Eneanya, N.D.; Nunes, J.W. The Relationship of Disease-Specific Knowledge and Health Literacy with the Uptake of Self-Care Behaviors in CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 5, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, J.-Z.; Wei, C.-J.; Weng, S.-F.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Shih, J.-H.; Shih, C.-L.; Chiu, C.-H. Disease-Specific Health Literacy, Disease Knowledge, and Adherence Behavior among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carden, M.A.; Newlin, J.; Smith, W.; Sisler, I. Health Literacy and Disease-Specific Knowledge of Caregivers for Children with Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 33, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikediashi, B.G.; Ehrmann, C.; Michel, G. Health Literacy in Adolescents and Young Adults in Benin: French Translation and Validation of the Health Literacy Measure for Adolescents’ Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1428434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari, S.; Ramezankhani, A.; Montazeri, A.; Mehrabi, Y. Health Literacy Measure for Adolescents (HELMA): Development and Psychometric Properties. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, N.; Calhoun, C.; Hodges, J.R.; Nwosu, C.; Kang, G.; King, A.A.; Zhao, X.; Hankins, J.S. Evaluation of Factors Influencing Health Literacy in Adolescents and Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2019, 134 (Suppl. S1), 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, M.B.; Fujiya, R.; Kiriya, J.; Htay, Z.W.; Nakajima, K.; Fuse, R.; Wakabayashi, N.; Jimba, M. Health Literacy among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Manganello, J.A.; Richards, M. A Life Course Approach to Health Literacy: The Role of Gender, Educational Attainment and Lifetime Cognitive Capability. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, E.P. The Influence of Health Literacy on Emergency Department Utilization and Hospitalizations in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. Public Health Nurs. 2019, 36, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry Caldwell, E.; Killingsworth, E. The Health Literacy Disparity in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 26, e12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.J.; Lo, Y.T. Improving Patient Health Literacy in Hospitals—A Challenge for Hospital Health Education Programs. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 4415–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W.; Parker, R.M.; Williams, M.V.; Clark, W.S. Health Literacy and the Risk of Hospital Admission. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1998, 13, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Williams, M.V.; Scott, T.; Parker, R.M.; Green, D.; Ren, J.; Peel, J. Functional Health Literacy and the Risk of Hospital Admission among Medicare Managed Care Enrollees. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, R.; Shoker, M.; Chu, L.M.; Frehlick, R.; Ward, H.; Pahwa, P. Impact of Low Health Literacy on Patients’ Health Outcomes: A Multicenter Cohort Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friis, K.; Aaby, A.; Lasgaard, M.; Pedersen, M.H.; Osborne, R.H.; Maindal, H.T. Low Health Literacy and Mortality in Individuals with Cardiovascular Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Diabetes, and Mental Illness: A 6-Year Population-Based Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcherson, T.C.; Rowlee, P.B.; Abeles, J.; Cieri-Hutcherson, N.E. Systematic Review of Emergency Department Management of Vaso-occlusive Episodes in Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. J. Sick. Cell Dis 2025, 2, yoaf001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeru, S.; Spotts, E.; Chen, M. Sickle Cell Retinopathy: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. J. Med. Optom. (JoMO) 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.A.; Belle, S.H.; James, A.; King, A.A. The Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium. Specifying sickle cell disease interventions: A study protocol of the Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, A.M.; Aygun, B.; Nuss, R.; Rogers, Z.R.; Section on Hematology/Oncology; American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. Health Supervision for Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease: Clinical Report. Pediatrics 2024, 154, e2024066842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, C.; Anjankar, A.; Agrawal, J. Self-Medication with Antibiotics: An Element Increasing Resistance. Cureus 2022, 14, e30844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limwado, G.D.; Aron, M.B.; Mpinga, K.; Phiri, H.; Chibvunde, S.; Banda, C.; Ndarama, E.; Walyaro, C.; Connolly, E. Prevalence of antibiotic self-medication and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance among community members in Neno District rural Malawi: A cross-sectional study. IJID Reg. 2024, 13, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozadeh, B.; Parandeh, A.; Khamseh, F.; Goharrizi, M.A.S.B. The Effect of Culturally Appropriate Self-Care Intervention on Health Literacy, Health-Related Quality of Life and Glycemic Control in Iranian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2023, 28, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhou, X.; Ma, L.-L.; Sun, T.-W.; Bishop, L.; Gardiner, F.W.; Wang, L. A Nurse-led Structured Education Program Improves Self-management Skills and Reduces Hospital Readmissions in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: A Randomized and Controlled Trial in China. Rural Remote Health 2019, 19, 5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, R.N.; Ummate, I.; Ohieku, J.D.; Yakubu, S.I.; Adibe, M.O.; Okonta, M.J. Kidney Disease Knowledge and Its Determinants Among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikediashi, B.G.; Ehrmann, C.; Gomez, S.; Michel, G. Disease Knowledge and Health Literacy in Parents of Children with Sickle Cell Disease. eJHaem 2023, 4, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, R.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Feng, D.; Feng, Z. Chronic Disease Knowledge and Its Determinants among Chronically Ill Adults in Rural Areas of Shanxi Province in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnani, M.R.; Barton-Gooden, A.; Grindley, M.; Knight-Madden, J. Disease Knowledge, Illness Perceptions, and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease: Is There a Link? Glob. Pediatr. Health 2017, 4, 2333794X17739194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netere, A.K.; Ashete, E.; Gebreyohannes, E.A.; Belachew, S.A. Evaluations of Knowledge, Skills and Practices of Insulin Storage and Injection Handling Techniques of Diabetic Patients in Ethiopian Primary Hospitals. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.J.; Chang, Y.J.; Liao, K.; Chen, C.D. Modest Association between Health Literacy and Risk for Peripheral Vascular Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 946889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.M.; Ramsbotham, J.; Seib, C.; Muir, R.; Bonner, A. A Scoping Review of the Role of Health Literacy in Chronic Kidney Disease Self-Management. J. Ren. Care 2021, 47, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qobadi, M.; Besharat, M.A.; Rostami, R.; Rahiminezhad, A. Health Literacy and Medical Adherence in Hemodialysis Patients: The Mediating Role of Disease-Specific Knowledge. Thrita J. Neuron 2015, 4, e26195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.5 | 2.5 |

| N | % | |

| SCD Type | ||

| βS/βS | 106 | 80.9 |

| βS/βC & βS/β0 | 25 | 19.1 |

| Transfusion History | ||

| Yes | 117 | 89.3 |

| No | 14 | 10.7 |

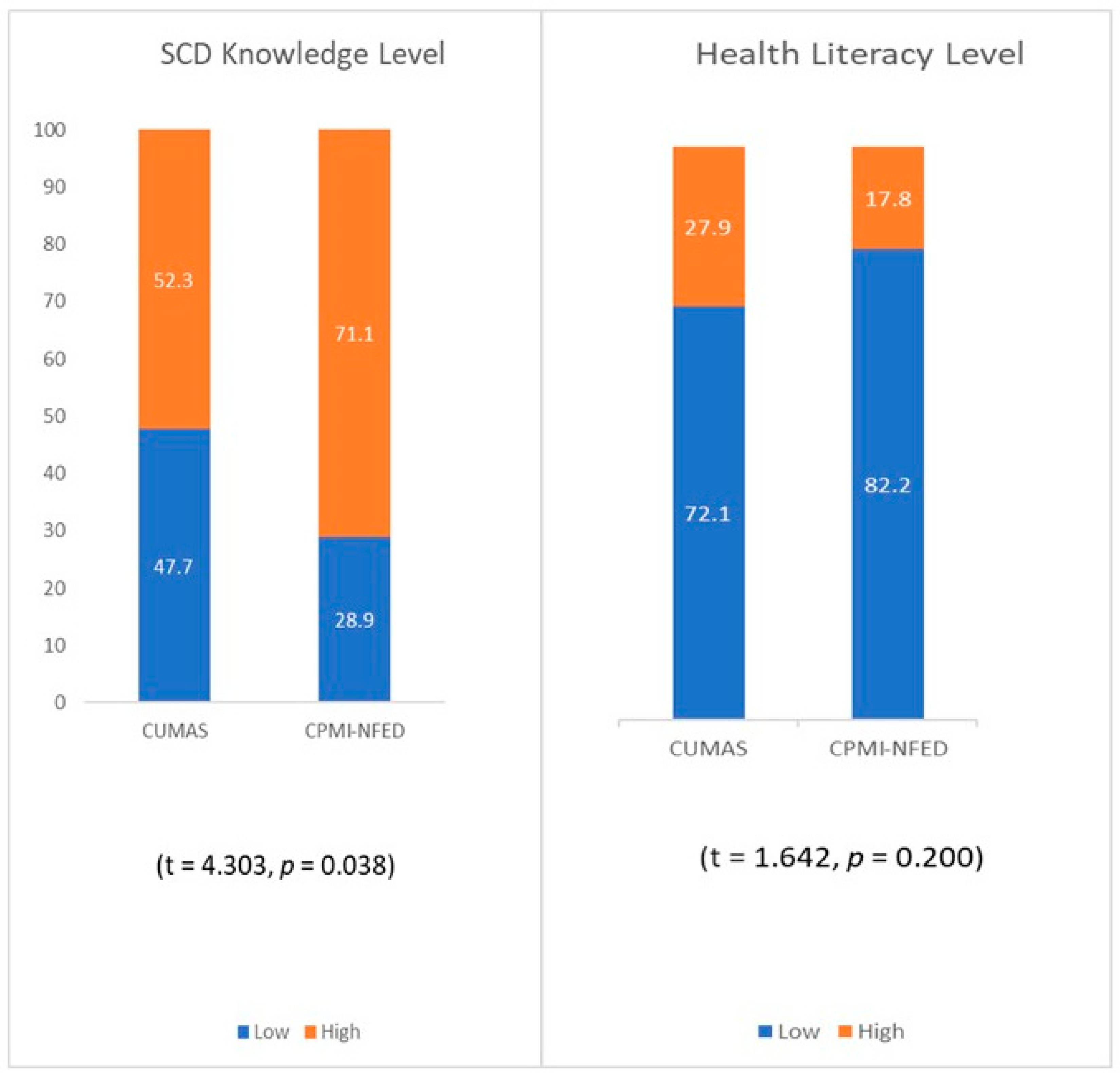

| Treatment Centre | ||

| CUMAS | 86 | 65.6 |

| CPMI-NFED | 45 | 34.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 66 | 50.4 |

| Female | 65 | 49.6 |

| Education Level | ||

| Secondary | 78 | 59.5 |

| Tertiary | 53 | 40.5 |

| Father’s Education Level | ||

| Primary | 57 | 43.5 |

| Secondary | 60 | 45.8 |

| tertiary | 14 | 10.7 |

| Mother’s Education Level | ||

| Primary | 31 | 23.7 |

| Secondary | 65 | 49.6 |

| Tertiary | 35 | 26.7 |

| Father’s Employment | ||

| Salaried | 57 | 43.5 |

| Self-employed | 67 | 51.2 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 5.3 |

| Mother’s Employment | ||

| Salaried | 36 | 27.5 |

| Self-employed | 82 | 62.6 |

| Unemployed | 13 | 9.9 |

| Health Literacy | ||

| Inadequate | 99 | 75.6 |

| Adequate | 32 | 24.4 |

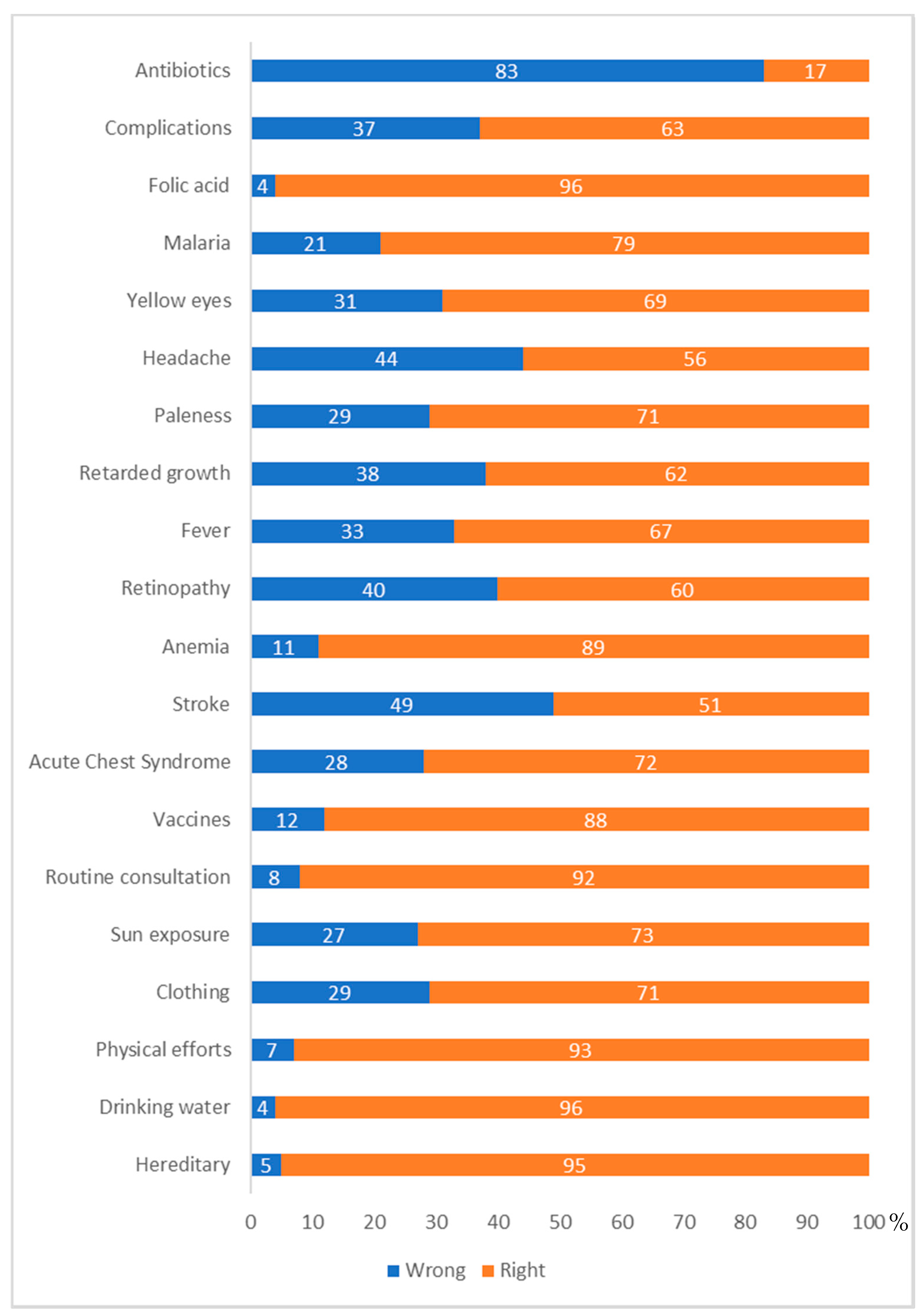

| Disease Knowledge | ||

| Low | 54 | 41.2 |

| High | 77 | 58.8 |

| SCD Knowledge | Health Literacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p Value | CI | β | p Value | CI | |

| Age | 0.466 | 0.000 | [0.263, 0.670] | 5.810 | 0.000 | [5.084, 6.535] |

| Female | −0.284 | 0.552 | [−1.227, 0.659] | 0.052 | 0.976 | [−3.316, 3.420] |

| Tertiary (ref: secondary education) | −0.071 | 0.892 | [−1.105, 0.093] | 4.286 | 0.023 | [0.593, 7.978] |

| Father’s Education Level (ref: tertiary education) | ||||||

| Secondary | 0.273 | 0.586 | [−0.717, 1.263] | 3.434 | 0.057 | [−0.101, 6.970] |

| Primary | 0.017 | 0.984 | [−1.659, 1.694] | 2.917 | 0.337 | [−3.070, 8.904] |

| Mother Education Level (ref: tertiary education) | ||||||

| Secondary | 0.963 | 0.125 | [−0.270, 2.195] | −3.819 | 0.088 | [−8.221, 0.583] |

| Primary | 0.587 | 0.408 | [−0.812, 1.985] | 0.467 | 0.853 | [−4.528, 5.462] |

| Father’s Employment Status (ref: employed) | ||||||

| Self-employed | −0.094 | 0.842 | [−1.031, 0.842] | 1.785 | 0.293 | [−1.562, 5.132] |

| Unemployed | −0.346 | 0.751 | [−2.501, 1.809] | 3.864 | 0.322 | [−3.834, 11.561] |

| Mother’s employment Status (ref: employed) | ||||||

| Self-employed | 0.569 | 0.314 | [−0.546, 1.685] | −0.263 | 0.896 | [−4.247, 3.72] |

| Unemployed | −1.027 | 0.254 | [−2.801, 0.747] | −2.188 | 0.495 | [−8.523, 4.147] |

| IRR | p Value | CI | IRR | p Value | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SCD knowledge | 0.777 | 0.046 | [0.607, 0.995] | |||

| Adequate Health Literacy | 0.662 | 0.075 | [0.42, 1.043] | |||

| Age | 0.974 | 0.397 | [0.917, 1.035] | 1.016 | 0.704 | [0.935, 1.105] |

| Female | 1.130 | 0.350 | [0.875, 1.459] | 1.189 | 0.192 | [0.917, 1.543] |

| Tertiary Education | 0.964 | 0.804 | [0.725, 1.283] | 0.934 | 0.640 | [0.701, 1.244] |

| Father’s Education Level | ||||||

| Secondary | 0.921 | 0.534 | [0.709, 1.195] | 0.904 | 0.447 | [0.697, 1.172] |

| Primary | 0.842 | 0.454 | [0.538, 1.320] | 0.847 | 0.467 | [0.542, 1.325] |

| Mother Education Level | ||||||

| Secondary | 1.063 | 0.717 | [0.763, 1.482] | 0.994 | 0.971 | [0.713, 1.386] |

| Primary | 1.077 | 0.691 | [0.747, 1.554] | 1.063 | 0.745 | [0.736, 1.536] |

| Father’s Employment Status | ||||||

| Self-employed | 1.019 | 0.885 | [0.794, 1.306] | 1.015 | 0.905 | [0.793, 1.300] |

| Unemployed | 0.703 | 0.308 | [0.358, 1.383] | 0.697 | 0.294 | [0.355, 1.368] |

| Mother’s employment Status | ||||||

| Self-employed | 1.097 | 0.542 | [0.815, 1.477] | 1.094 | 0.554 | [0.813, 1.471] |

| Unemployed | 1.212 | 0.427 | [0.755, 1.946] | 1.210 | 0.425 | [0.757, 1.934] |

| Transfusion history | 1.158 | 0.425 | [0.807, 1.662] | 1.227 | 0.266 | [0.855, 1.760] |

| SCD Type | 0.989 | 0.946 | [0.716, 1.366] | 1.015 | 0.929 | [0.735, 1.401] |

| IRR | p Value | CI | IRR | p Value | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SCD knowledge | 0.764 | 0.162 | [0.524, 1.114] | |||

| Adequate Health Literacy | 1.244 | 0.528 | [0.632, 2.448] | |||

| Age | 0.982 | 0.702 | [0.896, 1.076] | 0.939 | 0.345 | [0.825, 1.070] |

| Female | 0.907 | 0.618 | [0.618, 1.331] | 0.893 | 0.572 | [0.604, 1.321] |

| Tertiary Education | 0.968 | 0.880 | [0.634, 1.486] | 0.991 | 0.965 | [0.645, 1.521] |

| Father’s Education Level | ||||||

| Secondary | 1.023 | 0.909 | [0.689, 1.521] | 1.009 | 0.966 | [0.680, 1.497] |

| Primary | 1.012 | 0.971 | [0.525, 1.950] | 1.076 | 0.829 | [0.555, 2.085] |

| Mother Education Level | ||||||

| Secondary | 1.426 | 0.195 | [0.834, 2.436] | 1.396 | 0.225 | [0.814, 2.393] |

| Primary | 1.711 | 0.067 | [0.964, 3.037] | 1.683 | 0.076 | [0.947, 2.992] |

| Father’s Employment Status | ||||||

| Self-employed | 1.194 | 0.363 | [0.815, 1.749] | 1.203 | 0.340 | [0.823, 1.759] |

| Unemployed | 0.340 | 0.145 | [0.080, 1.451] | 0.353 | 0.159 | [0.083, 1.504] |

| Mother’s employment Status | ||||||

| Self-employed | 0.901 | 0.649 | [0.577, 1.409] | 0.897 | 0.633 | [0.575, 1.400] |

| Unemployed | 0.807 | 0.591 | [0.369, 1.766] | 0.854 | 0.692 | [0.391, 1.866] |

| Transfusion history | 0.979 | 0.943 | [0.549, 1.746] | 1.003 | 0.992 | [0.563, 1.786] |

| SCD Type | 0.849 | 0.550 | [0.497, 1.451] | 0.834 | 0.507 | [0.487, 1.427] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ikediashi, B.G.; Baglo-Agbodande, T.; Quenum, B.; Michel, G. Health Literacy and Disease Knowledge in Adolescents and Young Adults with SCD in Benin. Hemato 2025, 6, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040041

Ikediashi BG, Baglo-Agbodande T, Quenum B, Michel G. Health Literacy and Disease Knowledge in Adolescents and Young Adults with SCD in Benin. Hemato. 2025; 6(4):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040041

Chicago/Turabian StyleIkediashi, Bonaventure G., Tatiana Baglo-Agbodande, Bernice Quenum, and Gisela Michel. 2025. "Health Literacy and Disease Knowledge in Adolescents and Young Adults with SCD in Benin" Hemato 6, no. 4: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040041

APA StyleIkediashi, B. G., Baglo-Agbodande, T., Quenum, B., & Michel, G. (2025). Health Literacy and Disease Knowledge in Adolescents and Young Adults with SCD in Benin. Hemato, 6(4), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6040041