Plant-Derived Hydrolysates Are a Suitable Replacement for Tryptone N1 in Recombinant Protein Expression Using Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293-6E) Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

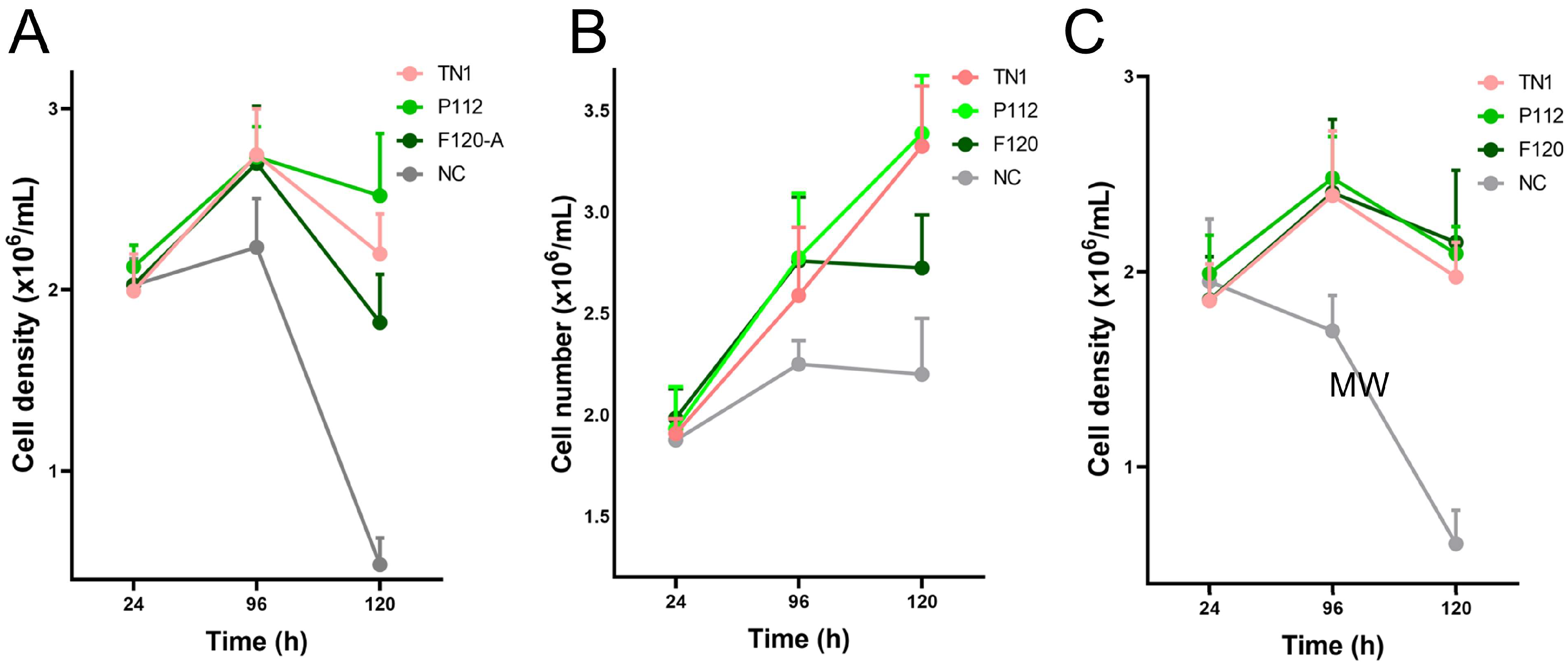

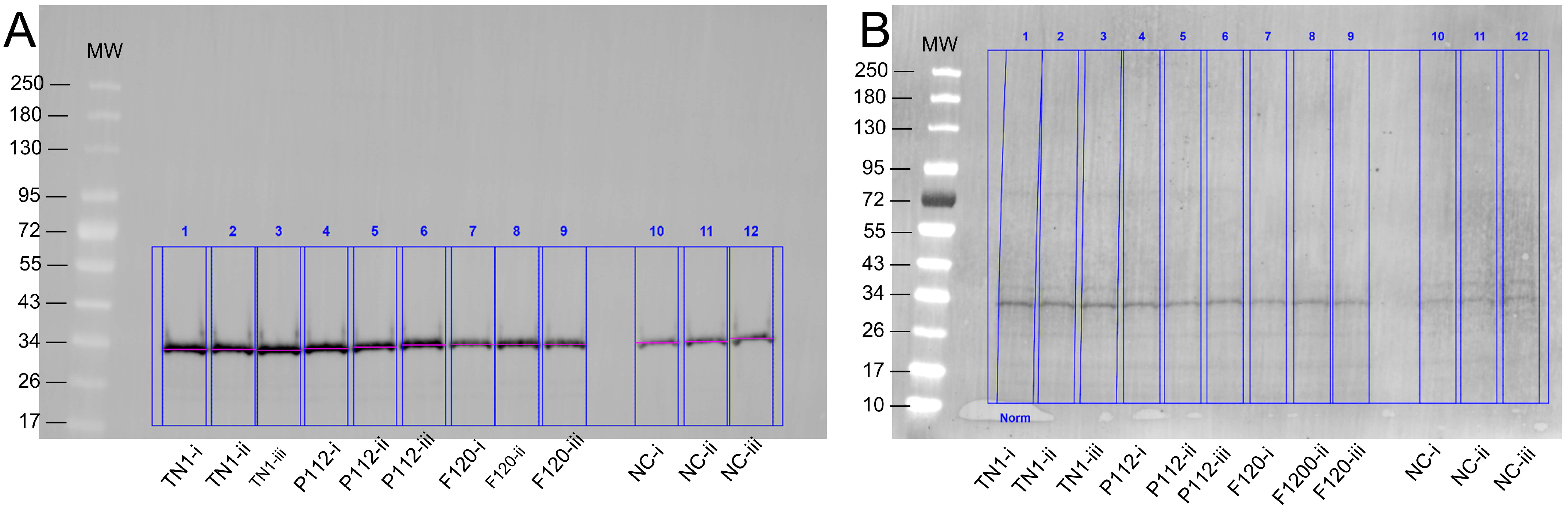

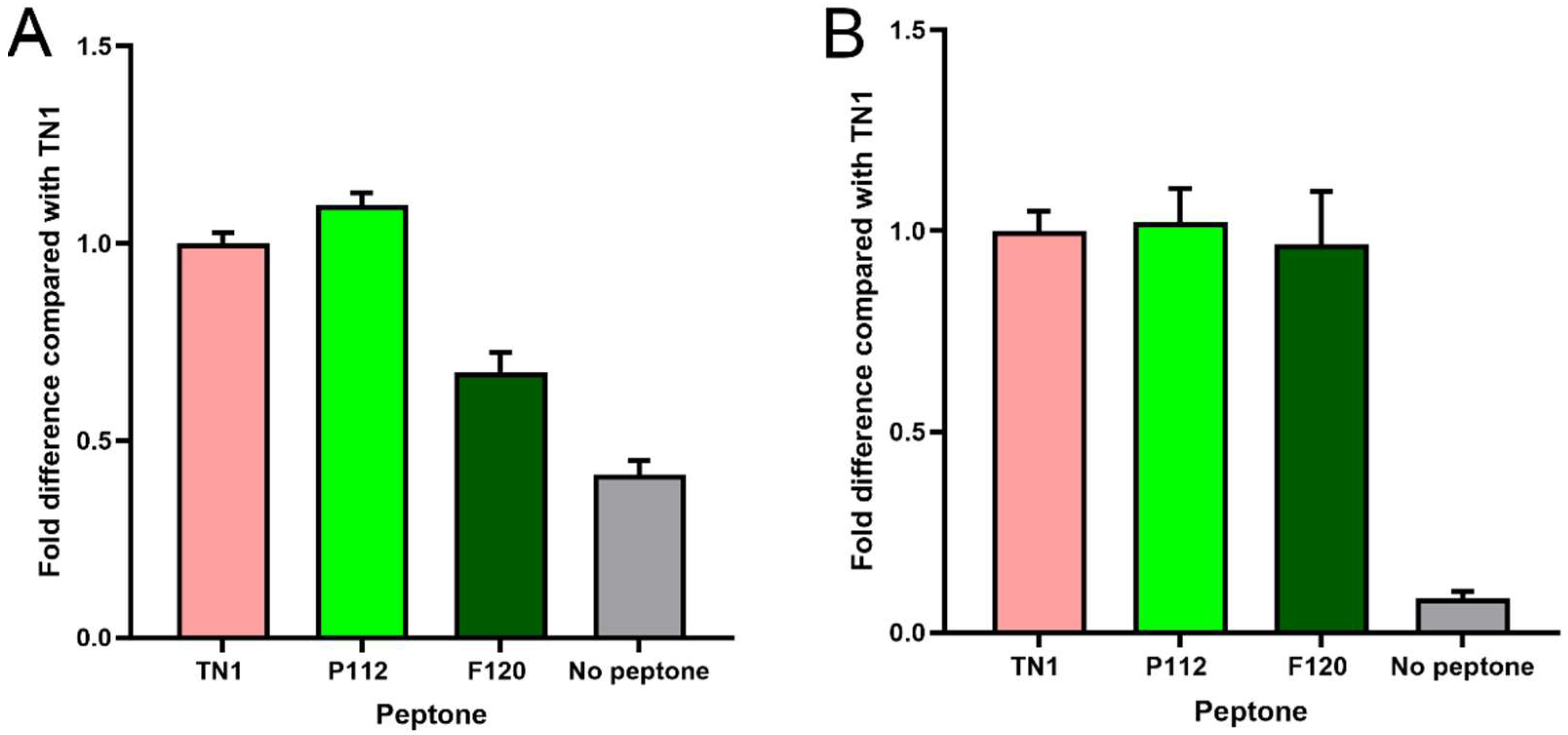

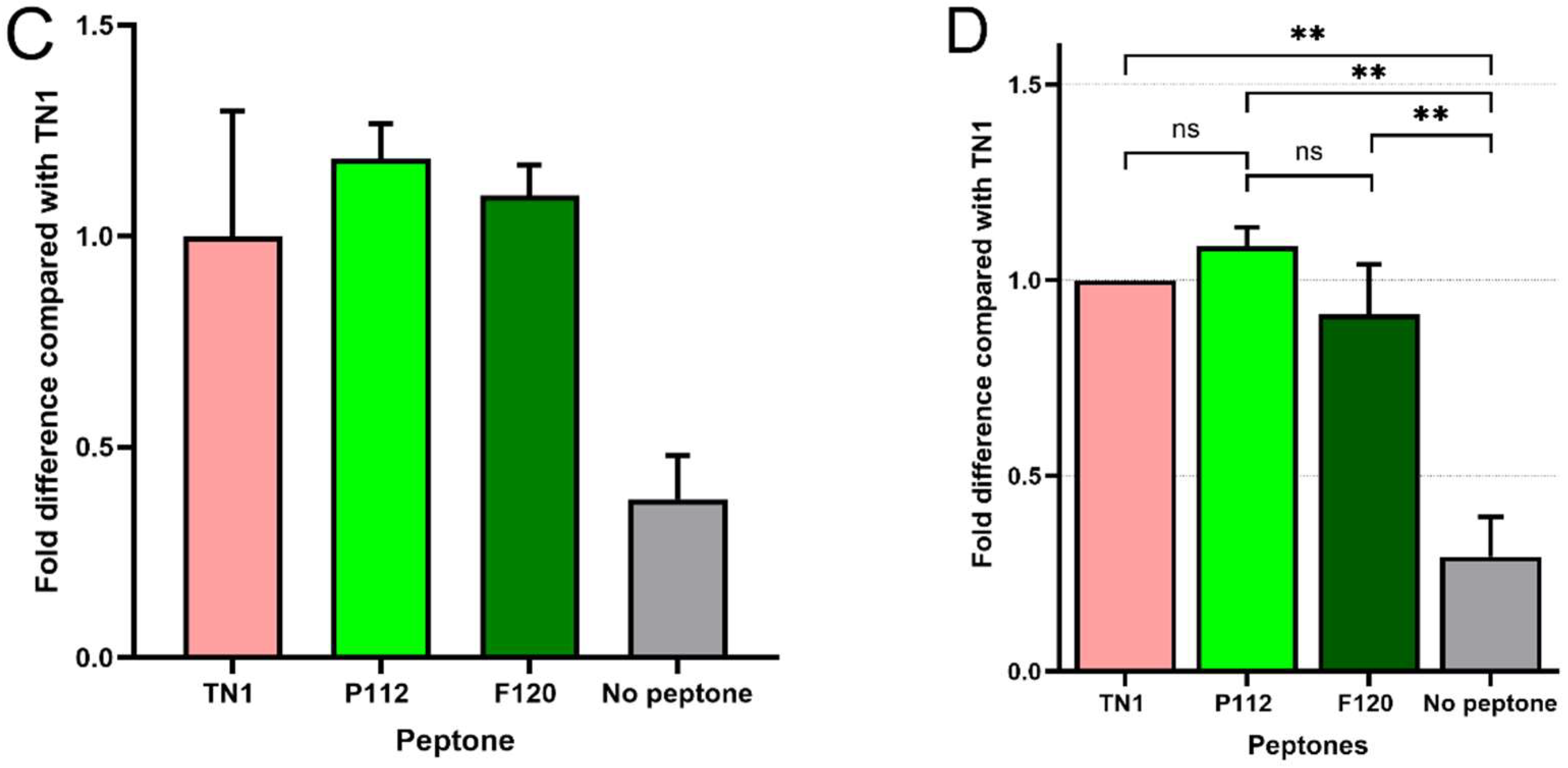

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. HEK293-6E Cell Culture

2.2. HEK293 Cell Transfection

2.3. Hydrolysate Feeding

2.4. Harvest

2.5. Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) Protein Precipitation

2.6. Determination of Combined Linear Dynamic Range and Quantification

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, W.; Cai, M. Advancing recombinant protein expression in Komagataella phaffii: Opportunities and challenges. FEMS Yeast Res. 2025, 25, foaf010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, E.; Chin, C.S.H.; Lim, Z.F.S.; Ng, S.K. HEK293 Cell Line as a Platform to Produce Recombinant Proteins and Viral Vectors. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 796991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demain, A.L.; Vaishnav, P. Production of recombinant proteins by microbes and higher organisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, L.; Hacker, D.L.; Adam, M.; Wurm, F.M. Recombinant protein production by large-scale transient gene expression in mammalian cells: State of the art and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davami, F.; Baldi, L.; Rajendra, Y.; Wurm, F.M. Peptone Supplementation of Culture Medium Has Variable Effects on the Productivity of CHO Cells. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2014, 3, 146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.; Köhne, C.; Wurm, F.M. Calcium-phosphate mediated DNA transfer into HEK-293 cells in suspension: Control of physicochemical parameters allows transfection in stirred media. Transfection and protein expression in mammalian cells. Cytotechnology 1998, 26, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.; Schallhorn, A.; Wurm, F.M. Transfecting mammalian cells: Optimization of critical parameters affecting calcium-phosphate precipitate formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.L.; Perret, S.; Doan, H.C.; Cass, B.; St-Laurent, G.; Kamen, A.; Durocher, Y. Large-scale transient transfection of serum-free suspension-growing HEK293 EBNA1 cells: Peptone additives improve cell growth and transfection efficiency. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 84, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, V.; Büssow, K.; Schirrmann, T. Transient Recombinant Protein Expression in Mammalian Cells. In Animal Cell Culture; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yingyongnarongkul, B.-E.; Radchatawedchakoon, W.; Krajarng, A.; Watanapokasin, R.; Suksamrarn, A. High transfection efficiency and low toxicity cationic lipids with aminoglycerol-diamine conjugate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulathanon, A.A.Y.; Ranucci, E.; Ferruti, P.; Garnett, M.C.; Bosquillon, C. Comparison of Gene Transfection and Cytotoxicity Mechanisms of Linear Poly(amidoamine) and Branched Poly(ethyleneimine) Polyplexes. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulhfard, S.; Tissot, S.; Bouchet, S.; Cevey, J.; de Jesus, M.; Hacker, D.L.; Wurm, F.M. Mild hypothermia improves transient gene expression yields several fold in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol. Prog. 2008, 24, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, V.; Groenewold, J.; Krüger, D.; Schwarz, D.; Vollmer, V. High-titer expression of recombinant antibodies by transiently transfected HEK 293-6E cell cultures. BMC Proc. 2015, 9, P40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosser, M.; Chevalot, I.; Olmos, E.; Blanchard, F.; Kapel, R.; Oriol, E.; Marc, I.; Marc, A. Combination of yeast hydrolysates to improve CHO cell growth and IgG production. Cytotechnology 2013, 65, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaeger, E.J. The protein hydrolysate, Primatone RL, is a cost-effective multiple growth promoter of mammalian cell culture in serum-containing and serum-free media and displays anti-apoptosis properties. J. Immunol. Methods 1996, 194, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidemann, R.; Zhang, C.; Qi, H.; Larrick Rule, J.; Rozales, C.; Park, S.; Chuppa, S.; Ray, M.; Michaels, J.; Konstantinov, K.; et al. The use of peptones as medium additives for the production of a recombinant therapeutic protein in high density perfusion cultures of mammalian cells. Cytotechnology 2000, 32, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, E.; Paris, S.; Kamen, A.A.; Durocher, Y. Limiting factors governing protein expression following polyethylenimine-mediated gene transfer in HEK293-EBNA1 cells. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 128, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández, B.A.; Calzadilla, L.; Enrico Bena, C.; Del Giudice, M.; Bosia, C.; Boggiano, T.; Mulet, R. Sodium acetate increases the productivity of HEK293 cells expressing the ECD-Her1 protein in batch cultures: Experimental results and metabolic flux analysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1335898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, L.; Fuenmayor, J.; González-Domínguez, I.; Gutiérrez-Granados, S.; Segura, M.M.; Gòdia, F. Selection and optimization of transfection enhancer additives for increased virus-like particle production in HEK293 suspension cell cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 9935–9949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, C.; Durocher, Y.; Henry, O. Exploiting the metabolism of PYC expressing HEK293 cells in fed-batch cultures. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 169, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulhfard, S.; Baldi, L.; Hacker, D.L.; Wurm, F. Valproic acid enhances recombinant mRNA and protein levels in transiently transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 148, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mo, R.; Yue, J.; Cheng, R.; Li, D.; Idres, Y.M.; Yang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Feng, R. Sodium valproate promotes low metabolism and high protein expression in CHO-engineered cell lines. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 208, 109362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.E.; Clémençon, B.; Hediger, M.A. Proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter family SLC15: Physiological, pharmacological and pathological implications. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajraktari-Sylejmani, G.; von Linde, T.; Burhenne, J.; Haefeli, W.E.; Sauter, M.; Weiss, J. Evaluation of PepT1 (SLC15A1) Substrate Characteristics of Therapeutic Cyclic Peptides. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonarius, H.P.J.; Hatzimanikatis, V.; Meesters, K.P.H.; de Gooijer, C.D.; Schmid, G.; Tramper, J. Metabolic flux analysis of hybridoma cells in different culture media using mass balances. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996, 50, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.L.; Perret, S.; Cass, B.; Carpentier, E.; St-Laurent, G.; Bisson, L.; Kamen, A.; Durocher, Y. Transient gene expression in HEK293 cells: Peptone addition posttransfection improves recombinant protein synthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 90, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Z.S.-L.; Yeo, J.Y.; Koh, D.W.-S.; Gan, S.K.-E.; Ling, W.-L. Augmenting recombinant antibody production in HEK293E cells: Optimizing transfection and culture parameters. Antibody Ther. 2022, 5, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Abbé, D.; Bisson, L.; Gervais, C.; Grazzini, E.; Durocher, Y. Transient Gene Expression in Suspension HEK293-EBNA1 Cells. In Recombinant Protein Expression in Mammalian Cells; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1850, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.C.; Posch, A. The design of a quantitative western blot experiment. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 361590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cregger, M.; Berger, A.J.; Rimm, D.L. Immunohistochemistry and quantitative analysis of protein expression. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2006, 130, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.C.; Berkelman, T.; Yadav, G.; Hammond, M. A defined methodology for reliable quantification of Western blot data. Mol. Biotechnol. 2013, 55, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M. Animal cell cultures: Recent achievements and perspectives in the production of biopharmaceuticals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 68, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franek, F.; Hohenwarter, O.; Katinger, H. Plant protein hydrolysates: Preparation of defined peptide fractions promoting growth and production in animal cells cultures. Biotechnol. Prog. 2000, 16, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L.; Jurcisek, J.A.; Trask, O.J.; Au, J.L. A method to monitor DNA transfer during transfection. AAPS PharmSci 1999, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai-Kastoori, L.; Schutz-Geschwender, A.R.; Harford, J.A. A systematic approach to quantitative Western blot analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 593, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.C.; Rosselli-Murai, L.K.; Crobeddu, B.; Plante, I. A critical path to producing high quality, reproducible data from quantitative western blot experiments. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shabir, S.; Hossain, M.S.; Egly, L.; Yalkin, G.; Falcone, F.H. Plant-Derived Hydrolysates Are a Suitable Replacement for Tryptone N1 in Recombinant Protein Expression Using Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293-6E) Cells. BioTech 2026, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech15010014

Shabir S, Hossain MS, Egly L, Yalkin G, Falcone FH. Plant-Derived Hydrolysates Are a Suitable Replacement for Tryptone N1 in Recombinant Protein Expression Using Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293-6E) Cells. BioTech. 2026; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleShabir, Shafqat, Md. Shahadat Hossain, Lucie Egly, Gizem Yalkin, and Franco H. Falcone. 2026. "Plant-Derived Hydrolysates Are a Suitable Replacement for Tryptone N1 in Recombinant Protein Expression Using Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293-6E) Cells" BioTech 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech15010014

APA StyleShabir, S., Hossain, M. S., Egly, L., Yalkin, G., & Falcone, F. H. (2026). Plant-Derived Hydrolysates Are a Suitable Replacement for Tryptone N1 in Recombinant Protein Expression Using Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293-6E) Cells. BioTech, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech15010014