A Comprehensive Review of Plant and Microbial Natural Compounds as Sources of Potential Helicobacter pylori-Inhibiting Agents

Abstract

1. Introduction

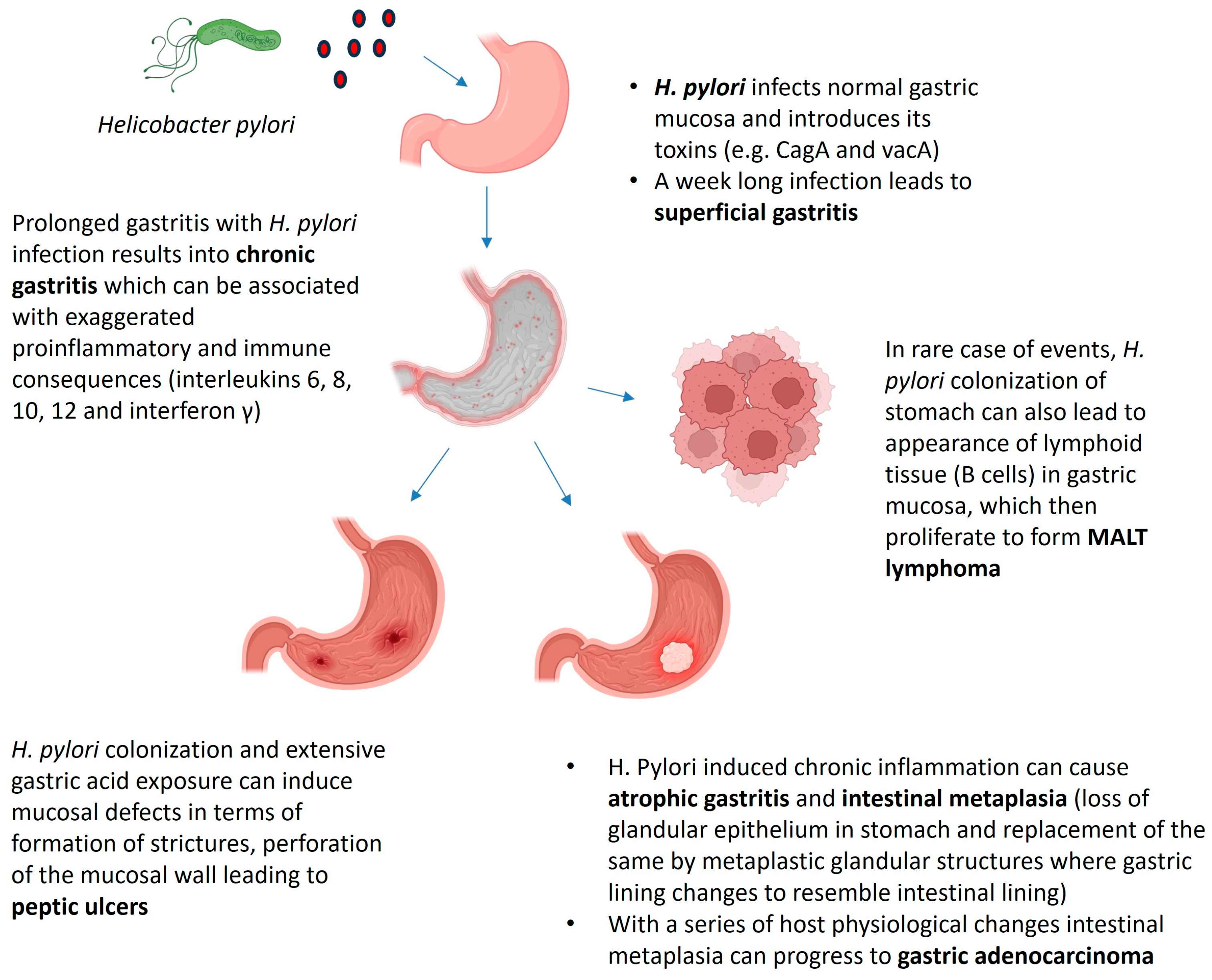

2. Helicobacter pylori: History of Infection and Associated Pathologies

3. Antibiotic Resistance in H. pylori: Paving the Way for Discovery of New Antibacterials

4. Bioactive Natural Products: The Improvement over Pharmaceutical Drugs

5. Plant and Microbial Natural Products as H. pylori Inhibitors

5.1. Inhibitors of H. pylori with a Specific Mechanism of Action

5.1.1. Inhibitors of H. pylori Cytotoxins

5.1.2. Inhibitors of H. pylori Urease

5.1.3. Inhibitors of H. pylori Homeostatic Stress Regulator A (HrsA)

5.1.4. Inhibitors of H. pylori Cystathionine γ-Synthase (CGS)

5.1.5. Inhibitors of H. pylori Fatty Acid, Protein and Vitamin Biosynthesis

5.1.6. Inhibitors of H. pylori Biofilm Formation

5.2. Inhibitors of H. pylori with No Specific Mechanism of Action

| Sl No. | Name of the Compounds | Chemical Classes | Sources of Isolation | Experimental Evidence | Dosage (MIC/IC50/%Inhibition) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | (1S,2R)-1,2-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanediol | Phenols | Root bark of Ulmus davidiana var. Japonica (Sarg. ex Rehder) Nakai | In vitro | 8–16 µg/mL | [57] |

| 2. | (2E)-1-[(5-Hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4-oxo-4H-1-benzopyran-3-yl)methyl]3-methyl-2-pentenedioate | Polyketides | culture filtrate of Trichoderma sp. | In vitro | 2–8 µg/mL | [71] |

| 3. | (2R,3S)-2-Ethoxychroman-3,5,7-triol-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside | Chromane derivatives | Root bark of Ulmus davidiana var. japonica (Sarg. ex Rehder) Nakai | In vitro | 10.5–21.2 µg/mL | [57] |

| 4. | (2S,3S)-5-Hydroxy-3-hydroxymethyl-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4-chromanone | Polyketides | culture filtrate of Trichoderma sp. | In vitro | 2–8 µg/mL | [71] |

| 5. | (9E)-11-Oxo-9-octadecenoic acid | Fatty acids | Fruiting bodies of Amanita hemibapha subsp. javanica | In vitro | 38% inhibition | [76] |

| 6. | (9E)-Methyl ester 9-octadecenoic acid | Fatty acids | Fruiting bodies of Amanita hemibapha subsp. javanica | In vitro | 80.5% inhibition | [76] |

| 7. | (Z)-Lanceol | Sesquiterpenoids | Heartwood of Santalum albumi L. | In vitro | 31.3–125 µg/mL | [56] |

| 8. | (Z)-α-Santalol | Sesquiterpenoids | Heartwood of Santalum album L. | In vitro | 7.8–31.3 µg/mL | [56] |

| 9. | (Z)-β-Santalol | Sesquiterpenoids | Heartwood of Santalum album L. | In vitro | 7.8–31.3 µg/mL | [56] |

| 10. | 2-Ethoxy-6-acetyl-7-methyljuglone | Naphthoquinones | Root extract of Reynoutria japonica (Houtt.) | In vitro | 0.04–0.08 µg/mL | [52] |

| 11. | 2-Methoxy-6-acetyl-7-methyljuglone | Naphthoquinones | Root extract of Reynoutria japonica (Houtt.) | In vitro | 0.05–0.07 µg/mL | [52] |

| 12. | 2-Methoxy-7-acetonyljuglone | Naphthoquinones | Root extract of Reynoutria japonica (Houtt.) | In vitro | 0.02–0.13 µg/mL | [52] |

| 13. | 3-Acetyl-7-methoxy-2-methyljuglone | Naphthoquinones | Root extract of Reynoutria japonica (Houtt.) | In vitro | 2.59–8.58 µg/mL | [52] |

| 14. | 3β,5α,6β-Trihydroxyergosta-7,22-diene | Sterols | Culture filtrates of Rhizoctonia sp. | In vitro | 25 µg/mL | [72] |

| 15. | 3β-Hydroxy-5α,8α-epidioxy- ergosta-6,22-diene | Sterols | Culture filtrates of Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 30 µg/mL | [73] |

| 16. | 4,6-Dihydroxy-2-methoxyphenyl-1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Phenol glycosides | Hypericum Erectum Thunberg | In vitro | 7.3 μg/mL | [53] |

| 17. | 4-Hydroxy-2,6-dimethoxyphenyl-1-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl(1-6)-β-D-glucopyranoside | Phenol glycosides | Hypericum Erectum Thunberg | In vitro | 27.3 μg/mL | [53] |

| 18. | Allicin | Thiosulfinic acid esters | Allium sativum L. | In vitro | 16 µg/mL | [59] |

| 19. | Allyl-methyl thiosulfinate | Alkanethiosulfinic acid esters | Allium sativum L. | In vitro | 24 µg/mL | [59] |

| 20. | Asperpyrone A | Bis-naphtho[2,3-b]pyrones | Culture filtrates of Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 4 μg/mL | [74] |

| 21. | Aurasperone A | Bis-naphtho[2,3-b]pyrones | Culture filtrates of Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 8–16 μg/mL | [74] |

| 22. | Aurasperone B | Bis-naphtho[2,3-b]pyrones | Culture filtrates of Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 8–16 μg/mL | [74] |

| 23. | Aurasperone F | Bis-naphtho[2,3-b]pyrones | Culture filtrates of Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 4 μg/mL | [74] |

| 24. | Berberine | Alkaloids | Dried tubers of Corydalis yanhusuo W.T. Wang | In vitro | 25 μg/mL | [60] |

| 25. | Cinnamaldehyde | Phenylpropanoids | Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J. Presl | In vitro | 2 μg/mL | [61] |

| 26. | CJ-13,136 | Alkaloids | Culture filtrates of Pseudonocardia sp. | In vitro | 0.0001 μg/mL | [69] |

| 27. | Dehydrocorydaline | Alkaloids | Dried tubers of Corydalis yanhusuo W.T. Wang | In vitro | 12.5 μg/mL | [60] |

| 28. | Demethylincisterol A3 | Ergosterol derivatives | Fruiting bodies of Daedaleopsis confragosa | In vitro | 33.9% inhibition | [75] |

| 29. | Eldaricoxide A | Diterpenoids | Needles of Pinus eldarica Medw. | In vitro | 29.49 μg/mL | [62] |

| 30. | Ergosterol | Sterols | Culture filtrates of Rhizoctonia sp. and Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 20–30 µg/mL | [72,73] |

| 31. | Ethyl galbanate | Sesquiterpene coumarins | Roots of Ferula pseudalliacea Rech.f. | In vitro | 64 μg/ml | [63] |

| 32. | Eugenol | Phenols | Clove oil | In vitro | 2 μg/mL | [64] |

| 33. | Fraxetin | Coumarins | Root bark of Ulmus davidiana var. japonica (Rehder) Nakai. | In vitro | 5.2–10.40 μg/mL | [57] |

| 34. | Helvolic acid | Steroids | Culture filtrates of Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 8 µg/mL | [73] |

| 35. | Heterophylliin G | Tannins | Corylus heterophylla Fisch. ex Trautv. | In vitro | 12.25–25 µg/mL | [58] |

| 36. | Lacticin A164 | Bacteriocins | Culture filtrates of Lactococcus lactis | In vitro | 0.097–0.390 µg/mL | [70] |

| 37. | Lacticin BH5 | Bacteriocins | Culture filtrates of Lactococcus lactis | In vitro | 0.097–0.390 µg/mL | [70] |

| 38. | Manoyl oxide acid | Diterpenoids | Needles of Pinus eldarica Medw. | In vitro | 26.72 μg/mL | [62] |

| 39. | Monomethylsulochrin | Benzophenones | Culture filtrates of Rhizoctonia sp. and Aspergillus sp. | In vitro | 10 µg/mL | [72,73] |

| 40. | Myricetin-3-O-β-D-glucuronide | Phenols | Potentilla spp. | In silico | -- | [65] |

| 41. | Nobotanin B | Tannins | Melastoma candidum D.Don | In vitro | 12.25–25 µg/mL | [58] |

| 42. | Olean-12-en-3-one | Triterpenoids | Figs of Ficus vallis-choudae Delile | In vitro | 6.1–10.4 µg/mL | [66] |

| 43. | Procyanidin B-5 | Tannins | Vitis vinifera L. | In vitro | 25–50 µg/mL | [58] |

| 44. | Quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside-6″-gallate | Phenols | Potentilla spp. | In silico | -- | [65] |

| 45. | Rhizoctonic acid | Benzophenones | Culture filtrates of Rhizoctonia sp. | In vitro | 25 µg/mL | [72] |

| 46. | Sanandajin | Disesquiterpene coumarins | Roots of Ferula pseudalliacea Boiss | In vitro | 64 μg/mL | [63] |

| 47. | Strictinin | Tannins | Elaeagnus umbellate Thunb. | In vitro | 6.25–25 µg/mL | [58] |

| 48. | Syringic acid | Phenols | Root barks of Ulmus davidiana var. japonica (Rehder) Nakai. | In vitro | 4.95–9.90 µg/mL | [57] |

| 49. | Tiliroside | Phenols | Potentilla spp. | In silico | -- | [65] |

6. Cytotoxicity as a Challenge in Anti-H. pylori Drug Development

7. Recent Approaches to Improve the Bioavailability and Efficacy of Natural Anti-H. pylori Agents

8. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atanasov, A.G.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.-M.; Linder, T.; Wawrosch, C.; Uhrin, P.; Temml, V.; Wang, L.; Schwaiger, S.; Heiss, E.H.; et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1582–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Desrosiers, J.; Aponte-Pieras, J.R.; DaSilva, K.; Fast, L.D.; Terry, F.; Martin, W.D.; De Groot, A.S.; Moise, L.; Moss, S.F. Human Immune Responses to H. pylori HLA Class II Epitopes Identified by Immunoinformatic Methods. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyanova, L.; Hadzhiyski, P.; Gergova, R.; Markovska, R. Evolution of Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Antibiotics: A Topic of Increasing Concern. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastergiou, V. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: Meeting the challenge of antimicrobial resistance. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Bonifácio, B.; Ramos, M.; Negri, K.; Maria Bauab, T.; Chorilli, M. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems and herbal medicines: A review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, B. A Brief History of the Discovery of Helicobacter pylori. In Helicobacter pylori; Suzuki, H., Warren, R., Marshall, B., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, J.G.; Van Vliet, A.H.M.; Kuipers, E.J. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M.; Reddy, K.M.; Marsicano, E. Peptic Ulcer Disease and Helicobacter pylori infection. Mo. Med. 2018, 115, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bashir, S.K.; Khan, M.B. Overview of Helicobacter pylori Infection, Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Its Prevention. Adv. Gut Microbiome Res. 2023, 2023, 9747027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Meng, W.; Wang, B.; Qiao, L. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014, 345, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fu, K. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and Helicobacter pylori infection: A review of current diagnosis and management. Biomark. Res. 2016, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Kusugami, K.; Ohsuga, M.; Ina, K.; Shinoda, M.; Konagaya, T.; Sakai, T.; Imada, A.; Kasuga, N.; Nada, T.; et al. Differential Normalization of Mucosal Interleukin-8 and Interleukin-6 Activity after Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 4742–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauditz, J.; Ortner, M.; Bierbaum, M.; Niedobitek, G.; Lochs, H.; Schreiber, S. Production of IL-12 in gastritis relates to infection with Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2001, 117, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, C.H.; Lundgren, A.; Azem, J.; Sjöling, Å.; Holmgren, J.; Svennerholm, A.-M.; Lundin, B.S. Natural Killer Cells and Helicobacter pylori Infection: Bacterial Antigens and Interleukin-12 Act Synergistically to Induce Gamma Interferon Production. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaoka, Y. Revolution of Helicobacter pylori treatment. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-Z.; Threapleton, D.E.; Wang, J.-Y.; Xu, J.-M.; Yuan, J.-Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, P.; Ye, Q.-L.; Guo, B.; Mao, C.; et al. Comparative effectiveness and tolerance of treatments for Helicobacter pylori: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 351, h4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; O’Morain, C.A.; Gisbert, J.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Axon, A.T.; Bazzoli, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Atherton, J.; Graham, D.Y.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—The Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017, 66, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Majlesi, M.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Herbal versus synthetic drugs; beliefs and facts. J. Nephropharmacol. 2015, 4, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lahlou, M. Screening of natural products for drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2007, 2, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, G.W.; Ghobadi, F.; Kalantari, H. Synthetic drugs: A new trend and the hidden danger. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamama, K. Synthetic drugs of abuse. In Advances in Clinical Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 103, pp. 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baj, J.; Forma, A.; Sitarz, M.; Portincasa, P.; Garruti, G.; Krasowska, D.; Maciejewski, R. Helicobacter pylori Virulence Factors—Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogenicity in the Gastric Microenvironment. Cells 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata-Kamiya, N.; Kikuchi, K.; Hayashi, T.; Higashi, H.; Hatakeyama, M. Helicobacter pylori Exploits Host Membrane Phosphatidylserine for Delivery, Localization, and Pathophysiological Action of the CagA Oncoprotein. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Greenfield, L.K.; Bronte-Tinkew, D.; Capurro, M.I.; Rizzuti, D.; Jones, N.L. VacA promotes CagA accumulation in gastric epithelial cells during Helicobacter pylori infection. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Kim, J.-B.; Lee, P.; Kim, S.-H. Evodiamine Inhibits Helicobacter pylori Growth and Helicobacter pylori-Induced Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Woo, H.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Kim, J.-B.; Kim, S.-H. Hesperetin Inhibits Expression of Virulence Factors and Growth of Helicobacter pylori. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.W.; Kwon, H.J.; Park, M.; Kim, S.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, J.-B. Inhibitory Effects of β-Caryophyllene on Helicobacter pylori Infection In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisto, F.; Carradori, S.; Guglielmi, P.; Spano, M.; Secci, D.; Granese, A.; Sobolev, A.P.; Grande, R.; Campestre, C.; Di Marcantonio, M.C.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of Thymol-Based Synthetic Derivatives as Dual-Action Inhibitors against Different Strains of H. pylori and AGS Cell Line. Molecules 2021, 26, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, H.; Ahmad, I.Z. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation Analysis of Thymoquinone and Thymol Compounds from Nigella sativa L. that Inhibit Cag A and Vac A Oncoprotein of Helicobacter pylori: Probable Treatment of H. pylori Infections. Med. Chem. 2020, 17, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarsia, C.; Danielli, A.; Florini, F.; Cinelli, P.; Ciurli, S.; Zambelli, B. Targeting Helicobacter pylori urease activity and maturation: In-cell high-throughput approach for drug discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 2245–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, M.M.; El-Fishawy, A.M.; El-Rashedy, A.A.; El Gedaily, R.A. Phytochemical Investigation of Cordia africana Lam. Stem Bark: Molecular Simulation Approach. Molecules 2022, 27, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, C. Sanguinarine, a major alkaloid from Zanthoxylum nitidum (Roxb.) DC., inhibits urease of Helicobacter pylori and jack bean: Susceptibility and mechanism. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 295, 115388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Tawalbeh, D.; Aburjai, T.; Al Balas, Q.; Al Samydai, A. In Silico and In Vitro Investigation of Anti Helicobacter Activity of Selected Phytochemicals. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2022, 14, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, H.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Lee, P.; Kim, J.-B.; Kim, S.-H. Zerumbone Inhibits Helicobacter pylori Urease Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, R.; Al-Rajhi, A.M.H.; Alzaid, S.Z.; Al Abboud, M.A.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Selim, S.; Ismail, K.S.; Abdelghany, T.M. Molecular Docking and Efficacy of Aloe vera Gel Based on Chitosan Nanoparticles against Helicobacter pylori and Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Polymers 2022, 14, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, R.; Khatkar, A. In-silico Designing, ADMET Analysis, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Derivatives of Diosmin Against Urease Protein and Helicobacter pylori Bacterium. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 2658–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, J.; Lanas, Á.; González, A. Two-component regulatory systems in Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni: Attractive targets for novel antibacterial drugs. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 977944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Salillas, S.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Espinosa Angarica, V.; Fillat, M.F.; Sancho, J.; Lanas, Á. Identifying potential novel drugs against Helicobacter pylori by targeting the essential response regulator HsrA. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-C. Medicinal plant activity on Helicobacter pylori related diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, M.A.; Szendzielorz, K.; Mazur, B.; Król, W. The inhibitory effect of flavonoids on interleukin-8 release by human gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cells infected with cag PAI (+) Helicobacter pylori. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 3, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Wu, D.; Bai, H.; Han, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Hu, L.; Jiang, H.; Shen, X. Enzymatic Characterization and Inhibitor Discovery of a New Cystathionine -Synthase from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biochem. 2007, 143, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, J.; Toledo, H.; Salas, F.; Guerrero, A.; Rios, D.; Valderrama, J.A.; Calderon, P.B. In Vitro Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori Growth by Redox Cycling Phenylaminojuglones. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1618051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Du, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Jiang, H. Helicobacter pylori acyl carrier protein: Expression, purification, and its interaction with β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase. Protein Expr. Purif. 2007, 52, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, J.; Ding, J.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shen, X. Emodin targets the β-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase from Helicobacter pylori: Enzymatic inhibition assay with crystal structural and thermodynamic characterization. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Han, C.; Hu, T.; Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Ding, J.; Chen, K.; Yue, J.; et al. Peptide deformylase is a potential target for anti- Helicobacter pylori drugs: Reverse docking, enzymatic assay, and X-ray crystallography validation. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.; Lu, W.; Zhu, L.; Shen, X.; Huang, J. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), an active component of propolis, inhibits Helicobacter pylori peptide deformylase activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 435, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasceno, J.; Rodrigues, R.; Gonçalves, R.; Kitagawa, R. Anti-Helicobacter pylori Activity of Isocoumarin Paepalantine: Morphological and Molecular Docking Analysis. Molecules 2017, 22, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.-Y.; Yao, J.-C.; Tang, S.-K.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.-W.; Li, W.-J. The Futalosine Pathway Played an Important Role in Menaquinone Biosynthesis during Early Prokaryote Evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Matsui, H.; Yamaji, K.; Takahashi, T.; Øverby, A.; Nakamura, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Nonaka, K.; Sunazuka, T.; Ōmura, S.; et al. Narrow-spectrum inhibitors targeting an alternative menaquinone biosynthetic pathway of Helicobacter pylori. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 22, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrar, E.; Albakry, Z.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Wu, D.; Li, J. Docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid from microalgae: Extraction, purification, separation, and analytical methods. Algal Res. 2024, 77, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, H.; Osaki, T.; Kamiya, S. Biofilm Formation by Helicobacter pylori and Its Involvement for Antibiotic Resistance. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 914791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Kumar, A.; Verma, V.K. Strategies Adopted by Gastric Pathogen Helicobacter pylori for a Mature Biofilm Formation: Antimicrobial Peptides as a Visionary Treatment. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 273, 127417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-J.; Qin, C.; Huang, G.-R.; Liao, L.-J.; Mo, X.-Q.; Huang, Y.-Q. Phillygenin Inhibits Helicobacter pylori by Preventing Biofilm Formation and Inducing ATP Leakage. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 863624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Hang, X.; Zeng, L.; Zhu, D.; Bi, H. Armeniaspirol A: A novel anti-Helicobacter pylori agent. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.A.K.; Park, W.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Akter, K.-M.; Goo, Y.-M.; Bae, J.-Y.; Chun, M.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Ahn, M.-J. A new anti-Helicobacter pylori juglone from Reynoutria japonica. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2019, 42, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J. Phenol Glycosides with In Vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori Activity from Hypericum erectum Thunb. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, T.; Shibata, H.; Higuti, T.; Kodama, K.; Kusumi, T.; Takaishi, Y. Anti-Helicobacter pylori Compounds from Santalum album. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.M.; Yu, J.S.; Khan, Z.; Subedi, L.; Ko, Y.-J.; Lee, I.K.; Park, W.S.; Chung, S.J.; Ahn, M.-J.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Chemical constituents of the root bark of Ulmus davidiana var. Japonica and their potential biological activities. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 91, 103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funatogawa, K.; Hayashi, S.; Shimomura, H.; Yoshida, T.; Hatano, T.; Ito, H.; Hirai, Y. Antibacterial Activity of Hydrolyzable Tannins Derived from Medicinal Plants against Helicobacter pylori. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004, 48, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañizares, P.; Gracia, I.; Gómez, L.A.; García, A.; De Argila, C.M.; Boixeda, D.; De Rafael, L. Thermal Degradation of Allicin in Garlic Extracts and Its Implication on the Inhibition of the in-Vitro Growth of Helicobacter pylori. Biotechnol. Prog. 2008, 20, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Sun, Q.; Dong, H.; Qiao, J.; Lin, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, Y. Gastroprotective action of the extract of Corydalis yanhusuo in Helicobacter pylori infection and its bioactive component, dehydrocorydaline. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 307, 116173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liao, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Luo, P.; Huang, G.; Huang, Y.-Q. Cinnamaldehyde: An effective component of Cinnamomum cassia inhibiting Helicobacter pylori. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 330, 118222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Na, M.W.; Park, E.C.; Kim, J.-C.; Kang, D.-M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Ahn, M.-J.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, K.H. Labdane-type Diterpenes from Pinus eldarica Needles and Their Anti-Helicobacter pylori Activity. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 29502–29507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastan, D.; Salehi, P.; Aliahmadi, A.; Gohari, A.R.; Maroofi, H.; Ardalan, A. New coumarin derivatives from Ferula pseudalliacea with antibacterial activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 2747–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.M.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, I.; Musaddiq, M.; Ahmed, K.S.; Polasa, H.; Rao, L.V.; Habibullah, C.M.; Sechi, L.A.; Ahmed, N. Antimicrobial activities of Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde against the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2005, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hřibová, P.; Khazneh, E.; Žemlička, M.; Švajdlenka, E.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Elokely, K.M.; Ross, S.A. Antiurease activity of plants growing in the Czech Republic. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankeu, J.J.K.; Sattar, H.; Fongang, Y.S.F.; Muhammadi, S.W.; Simoben, C.V.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Feuya, G.R.T.; Tchuenmogne, M.A.T.; Lateef, M.; Lenta, B.N.; et al. Synthesis, Urease Inhibition and Molecular Modelling Studies of Novel Derivatives of the Naturally Occurring β-Amyrenone. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2019, 9, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushnie, T.P.T.; Cushnie, B.; Lamb, A.J. Alkaloids: An overview of their antibacterial, antibiotic-enhancing and antivirulence activities. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-S.; Hur, J.-W.; Yu, M.-A.; Cheigh, C.-I.; Kim, K.-N.; Hwang, J.-K.; Pyun, Y.-R. Antagonism of Helicobacter pylori by Bacteriocins of Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, D.; Lan, D.; Liu, T.; Wu, B.; Bi, H.; Tang, J. New Polyketides from a Hydrothermal Vent Sediment Fungus Trichoderma sp. JWM29-10-1 and Their Antimicrobial Effects. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.M.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Song, Y.C.; Tan, R.X. Anti-Helicobacter pylori metabolites from Rhizoctonia sp. Cy064, an endophytic fungus in Cynodon dactylon. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, Y.C.; Liu, J.Y.; Ma, Y.M.; Tan, R.X. Anti-Helicobacter pylori substances from endophytic fungal cultures. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Jia, J.; Xue, Y.; Ding, W.; Dong, Z.; Tian, D.; Chen, M.; Bi, H.; Hong, K.; Tang, J. New pyrones and their analogs from the marine mangrove-derived Aspergillus sp. DM94 with antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 7971–7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, M.W.; Lee, E.; Kang, D.-M.; Jeong, S.Y.; Ryoo, R.; Kim, C.-Y.; Ahn, M.-J.; Kang, K.B.; Kim, K.H. Identification of Antibacterial Sterols from Korean Wild Mushroom Daedaleopsis confragosa via Bioactivity- and LC-MS/MS Profile-Guided Fractionation. Molecules 2022, 27, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Alishir, A.; Kim, T.W.; Kang, D.-M.; Ryoo, R.; Pang, C.; Ahn, M.-J.; Kim, K.H. First Chemical Investigation of Korean Wild Mushroom, Amanita hemibapha subsp. Javanica and the Identification of Anti-Helicobacter pylori Compounds. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElNaggar, M.H.; Abdelwahab, G.M.; Kutkat, O.; GabAllah, M.; Ali, M.A.; El-Metwally, M.E.A.; Sayed, A.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Khalil, A.T. Aurasperone A Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro: An Integrated In Vitro and In Silico Study. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriwardane, A.M.D.A.; Kumar, N.S.; Jayasinghe, L.; Fujimoto, Y. Chemical Investigation of Metabolites Produced by an Endophytic Aspergillus sp. Isolated from Limonia acidissima. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Qiu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, K.; Cao, Z.; Xiang Tan, R.; Tickner, J.; Xu, J.; Zou, J. Asperpyrone A Attenuates RANKL-induced Osteoclast Formation through Inhibiting NFATc1, Ca2+ Signalling and Oxidative Stress. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 8269–8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marking, L.L. Juglone (5-Hydroxy-1,4-Naphthoquinone) as a Fish Toxicant. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1970, 99, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, T.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Shi, W. New Advances in Nano-Drug Delivery Systems: Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 834934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Song, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, R.; Xie, Y.; Yu, L.; Yan, X. Advances in Micro/Nanodrug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection: From Diagnosis to Eradication. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 37, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molfetta, F.A.; Bruni, A.T.; Honório, K.M.; Da Silva, A.B.F. A Structure–Activity Relationship Study of Quinone Compounds with Trypanocidal Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qun, T.; Zhou, T.; Hao, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, K.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W. Antibacterial Activities of Anthraquinones: Structure–Activity Relationships and Action Mechanisms. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14, 1446–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, G.; Chopra, S. Diverse Chemotypes of Polyketides as Promising Antimicrobial Agents: Latest Progress. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 32080–32107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Tian, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, W.; Zhu, H.; Li, Q.; Lei, L.; Yao, G.; Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Fungal Naphtho-γ-Pyrones: Potent Antibiotics for Drug-Resistant Microbial Pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudrioua, A.; Baëtz, B.; Desmadril, S.; Goulard, C.; Groo, A.-C.; Lombard, C.; Gueulle, S.; Marugan, M.; Malzert-Fréon, A.; Hartke, A.; et al. Lasso Peptides Sviceucin and Siamycin I Exhibit Anti-Virulence Activity and Restore Vancomycin Effectiveness in Vancomycin-Resistant Pathogens. iScience 2025, 28, 111922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl No. | Name of the Compounds | Chemical Classes | Sources of Isolation | Experimental Evidence | Dosage (MIC/IC50/%Inhibition) | Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors of H. pylori cytotoxins | |||||||

| 1. | Evodiamine | Alkaloids | Fruits of Evodia rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth. | In vitro | 1.5–24.2 μg/mL | Down-regulation of urease and diminished translocation of CagA and VacA Down-regulation of gene expressions of replication and transcription machineries | [26] |

| 2. | Hesperetin | Flavonoids | Citrus fruits | In vitro | 4–8 μg/mL | Down-regulation of virulence gene expressions | [27,39] |

| 3. | β-Caryophyllene | Sesquiterpenes | Essential oil of Commiphora gileadensis (L.) C. Chr. | In vitro | 1000 µg/mL | Growth inhibition, down-regulation of virulence gene expressions | [28] |

| 4. | Thymol | Monoterpenoids | Nigella sativa L. | In silico | -- | CagA and VacA inhibition | [30] |

| 5. | Thymoquinone | Monoterpenoids | Nigella sativa L. | In silico | -- | CagA and VacA inhibition | [30] |

| Inhibitors of H. pylori urease | |||||||

| 6. | Chlorogenic acid | Phenols | Gel from Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. | In silico | -- | -- | [36] |

| 7. | Diosmin | Flavonoids | Citrus fruits | In silico | -- | -- | [37] |

| 8. | Methyl rosmarinate | Phenols | Stem bark of Cordia Africana Lam. | In vitro and in silico | 31.25 μg/mL | -- | [32] |

| 9. | Pyrocatechol | Phenols | Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. | In silico | -- | -- | [36] |

| 10. | Sanguinarine | Alkaloids | Zanthoxylum nitidum (Roxb.) DC. | In vitro | 159.5 μg/mL | -- | [33] |

| 11. | Terpineol | Monoterpenoids | Widely found in flowers like narcissus and freesia, in herbs including marjoram, oregano and rosemary and in lemon peel oil | In vitro and in silico | 1.443 μg/mL | -- | [34] |

| 12. | Zerumbone | Sesquiterpenoids | Zingiber zerumbet (L.) Roscoe ex Sm | In vitro | 10.91 μg/mL | [35] | |

| Inhibitors of H. pylori homeostatic stress regulator (HsrA) | |||||||

| 13. | Apigenin | Flavonoids | Widely present in cereals and red and yellow fruits | In vitro | 8 μg/mL | -- | [39] |

| 14. | Chrysin | Flavonoids | Widely present in cereals and red and yellow fruits | In vitro | 4–8 μg/mL | -- | [39] |

| 15. | Kaempferol | Flavonoids | Widely present in cereals and red and yellow fruits | In vitro | 4–8 μg/mL | -- | [39] |

| Inhibitors of H. pylori cystathionine γ-synthase (CGS) | |||||||

| 16. | 9-Hydroxy-α-lapachone | Naphthopyranones | Stems of Catalpa ovata G. Don. | In vitro | 2.32 µg/mL | -- | [42] |

| 17. | α-Lapachone | Naphthopyranones | Wood of Tabebuia heptaphylla (Vell.) Mattos. | In vitro | 2.66 µg/mL | -- | [42] |

| 18. | Juglone | Quinones | Roots of Juglans nigra L. and Juglans regia L. | In vitro | 1.21 µg/mL | -- | [42] |

| 19. | Paulownin | Lignans | Paulownia tomentosa Steud. | In vitro | 7.03 µg/mL | -- | [42] |

| 20. | Yangambin | Lignans | Ocotea fasciculata (Nees) Mez. | In vitro | 12.05 µg/mL | [42] | |

| Inhibitors of H. pylori fatty acid, protein and vitamin biosynthesis | |||||||

| 21. | Emodin | Anthraquinones | Rhizomes of Rheum palmatum L. and other traditional Chinese medicines | In vitro | 2.6 μg/mL | β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ) inhibition | [45] |

| 22. | Caffeic acid phenethyl ester | Phenols | Honey bee propolis | In vitro | 1.14 μg/mL | Peptide deformylase (pdf) inhibition | [47] |

| 23. | Paepalantine | Isocoumarins | Capitula of Paepalanthus bromelioides Silveira | In vitro and in silico | 128 μg/mL | Inhibiting membrane protein synthesis | [48] |

| 24. | Siamycin I | Bacteriocins | Culture filtrates of Streptomyces sp. | In vitro and in vivo | 5.4 μg/mL (H. pylori colonization was reduced by 68% in vivo) | Inhibition of futalosine pathway of melaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis | [49] |

| 25. | Docosahexaenoic acid | Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Culture filtrates of Schizochytrium sp. | In vitro and in vivo | 32.8 μg/mL (H. pylori colonization was reduced by 78% in vivo) | Inhibition of futalosine pathway of melaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis | [49] |

| 26. | Eicosapentaenoic acid | Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Culture filtrates of Phaeodactylum tricornutum | In vitro and in vivo | 30.2 μg/mL (H. pylori colonization was reduced by 96% in vivo) | Inhibition of futalosine pathway of melaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis | [49] |

| 27. | Juglone | Quinones | Roots of Juglans nigra L. and Juglans regia L. | In vitro | 3.48 and 5.22 µg/mL | Inhibition of malonyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein transacylase (FabD) and β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ) | [42] |

| Inhibition of biofilm formation in H. pylori | |||||||

| 28. | Phillygenin | Lignans | Leaves of Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl. | In vitro | 16–64 μg/mL | Biofilm inhibition | [54] |

| 29. | Armeniaspirol A | Polyketides | Culture filtrates of Streptomyces armeniacus | In vivo | 4–16 μg/mL | Biofilm inhibition | [55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Padhi, S.; Sharma, S.; Sarkar, P.; Masi, M.; Cimmino, A.; Rai, A.K. A Comprehensive Review of Plant and Microbial Natural Compounds as Sources of Potential Helicobacter pylori-Inhibiting Agents. BioTech 2025, 14, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040094

Padhi S, Sharma S, Sarkar P, Masi M, Cimmino A, Rai AK. A Comprehensive Review of Plant and Microbial Natural Compounds as Sources of Potential Helicobacter pylori-Inhibiting Agents. BioTech. 2025; 14(4):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040094

Chicago/Turabian StylePadhi, Srichandan, Swati Sharma, Puja Sarkar, Marco Masi, Alessio Cimmino, and Amit Kumar Rai. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review of Plant and Microbial Natural Compounds as Sources of Potential Helicobacter pylori-Inhibiting Agents" BioTech 14, no. 4: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040094

APA StylePadhi, S., Sharma, S., Sarkar, P., Masi, M., Cimmino, A., & Rai, A. K. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Plant and Microbial Natural Compounds as Sources of Potential Helicobacter pylori-Inhibiting Agents. BioTech, 14(4), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040094