Microbial Biosurfactants: Antimicrobial Agents Against Pathogens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Classification of Biosurfactants (BSs)

3. Microbial Sources for the Synthesis of Biosurfactants

- -

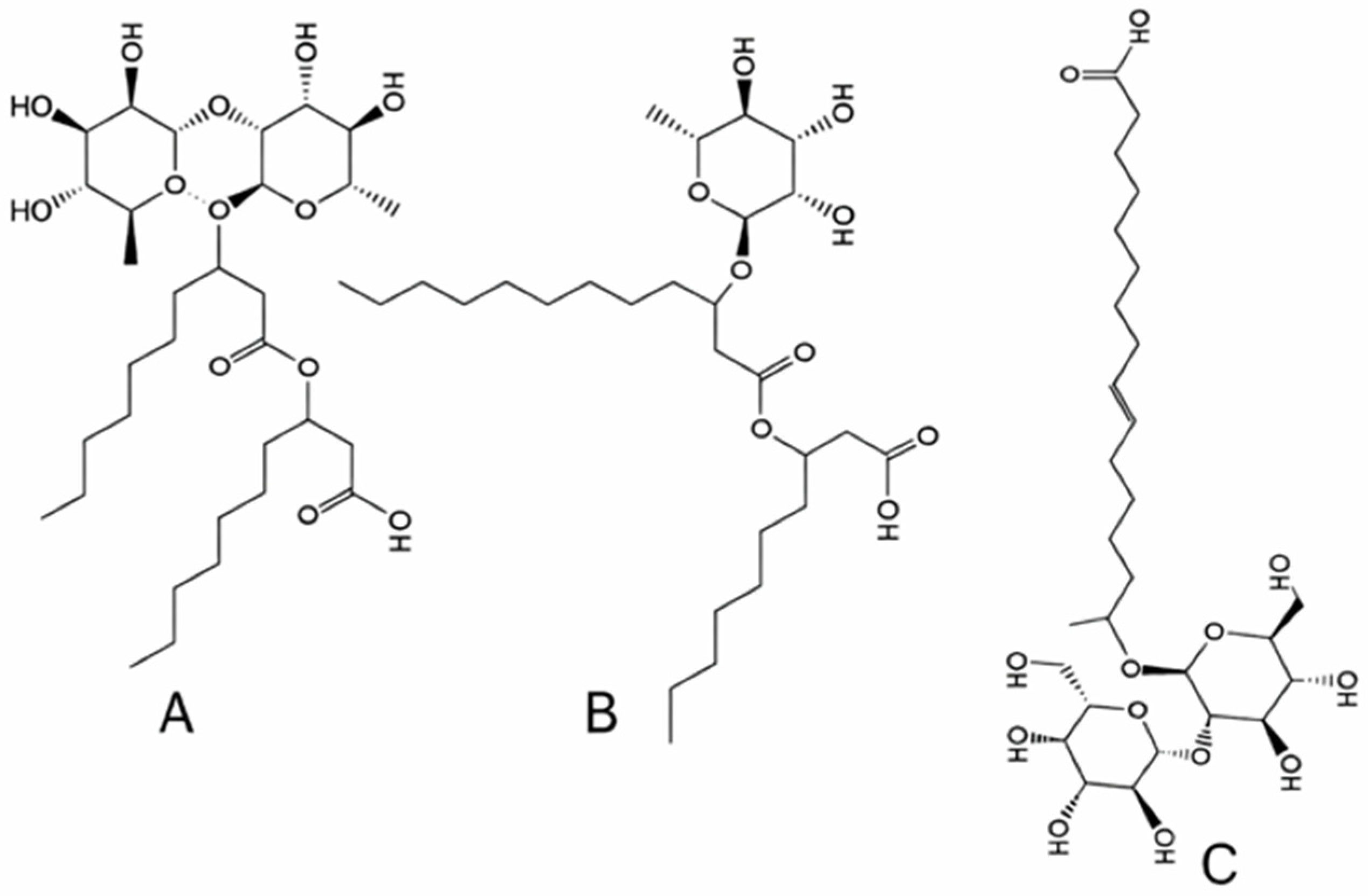

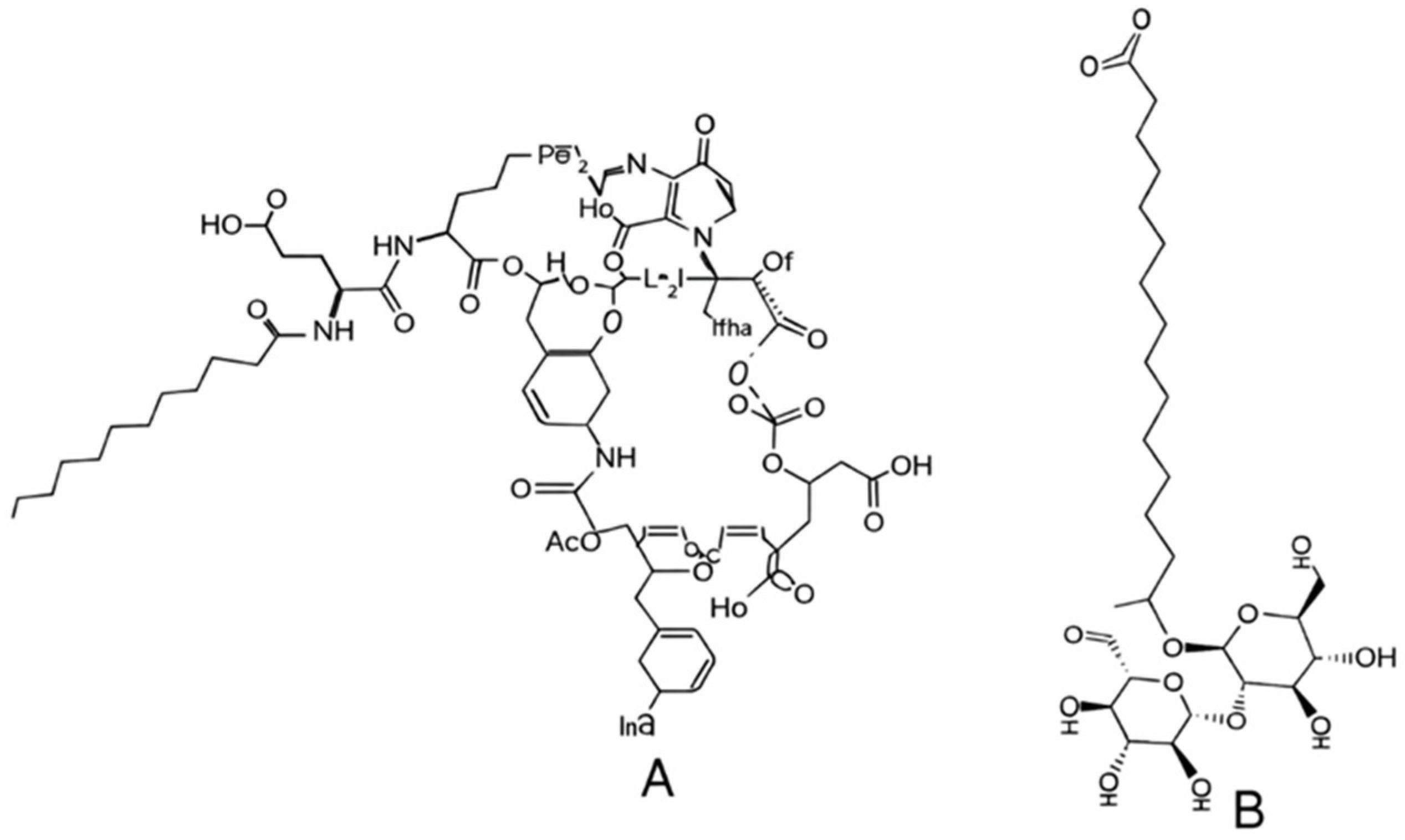

- Glycolipids such as rhamnolipids, sophorolipids, trehalolipids, and MELs share a common motif of carbohydrate headgroups linked to one or two fatty acid chains, resulting in low-molecular-weight molecules with strong surface activity and low CMC values.

- -

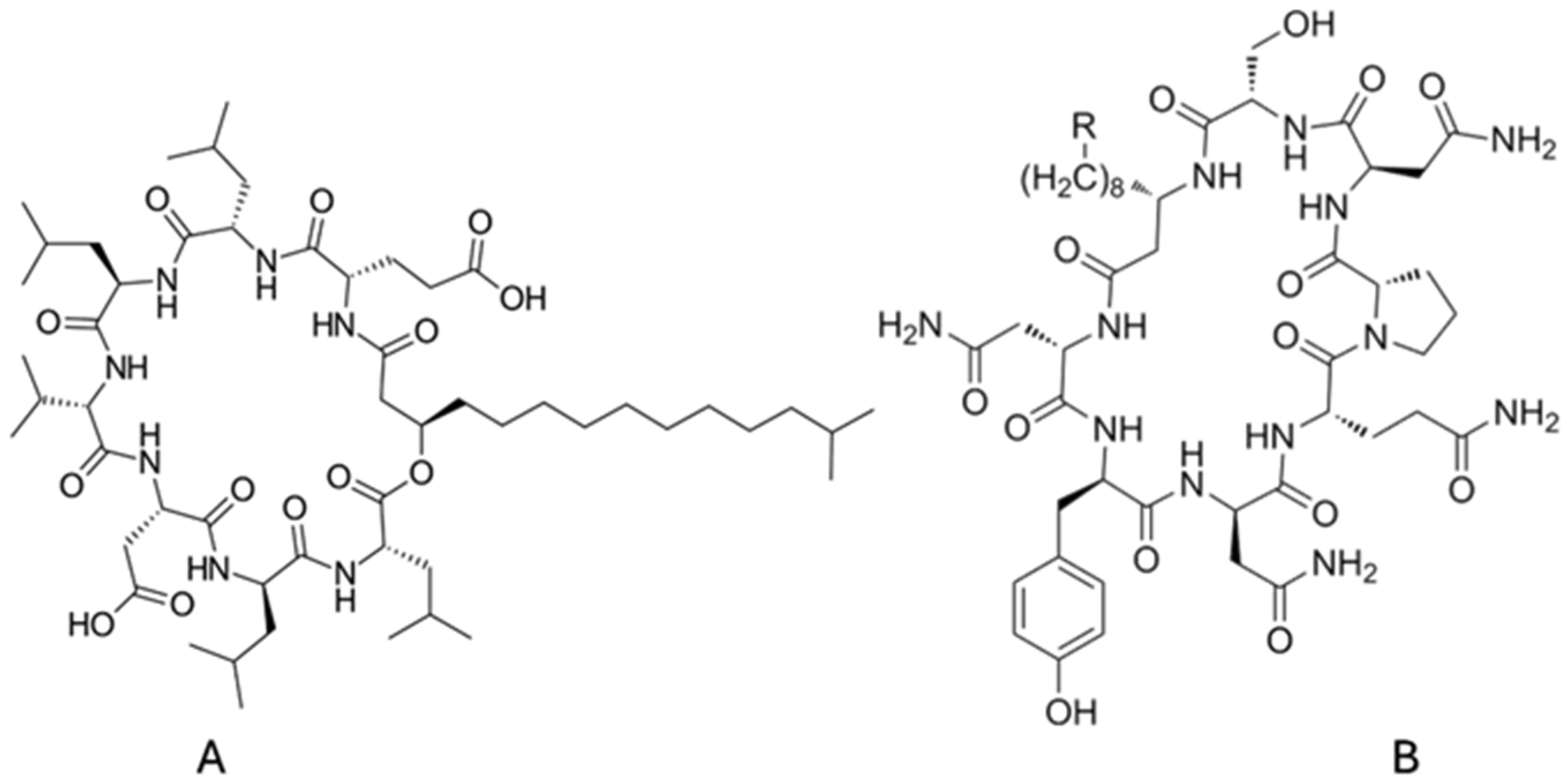

- Lipopeptides, including surfactin, iturin, fengycin, lichenysin, and viscosin, combine peptide rings with β-hydroxy fatty acids, conferring exceptional interfacial tension reduction, high thermal stability, and robust foaming properties.

- -

- Fatty acids and phospholipids exhibit classical amphipathic glycerol–phosphate structures that readily form bilayers and vesicles.

- -

- High-molecular-weight polymeric and particulate biosurfactants, such as emulsan, liposan, alasan, and vesicle-rich complexes, provide strong emulsification and steric stabilization due to their polysaccharide–protein matrices. These structural features align with the microbial producers listed in Table 3, as each taxonomic group preferentially synthesizes specific biosurfactant classes according to its metabolic pathways and cell envelope composition.

4. Key Chemical Compositions and Properties of Biosurfactants

5. Antimicrobial Activities of Biosurfactants

5.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Zone of Inhibition (ZOI)

5.2. Chemical Structures of Biosurfactants and Their Antimicrobial Properties

- -

- Positively charged biosurfactants have double killing effects. First, they attract the negatively charged bacterial membrane and disrupt the membranes. The second antimicrobial activity is attributed to their insertion into the bacterial membrane, resulting in physical disruption, like a needle bursting a balloon [104]. However, excessively long chains (above C16–C18) may decrease in activity due to solubility limits.

- -

- -

- -

- The chain unsaturation in diacetylated lactonic sophorolipids is also attributed to the antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, as C18:0 and C18:1 show a MIC (50 μg/mL), significantly lower than the values of C18:2 and C18:3 (200 μg/mL). Therefore, the presence of one or two double bonds in lactonic sophorolipids plays an important role in antimicrobial activity [106].

- -

- Antimicrobial properties of sophorolipids depend on the degree of acetylation. The MIC against B. cereus of diacetylated sophorolipids is 12 μM, which is significantly lower than 25 μM for sophorolipids [106].

- -

- -

- Some biosurfactants, like surfactin, can also chelate essential mono- or divalent cations, which further destabilizes the membrane and compromises its integrity [108].

6. Cytotoxicity

7. Synergistic Use of Biosurfactants with Conventional Antibiotics

8. Other Biomedical Applications of Biosurfactants

8.1. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Agents

8.2. Drug Delivery Systems

- -

- Enhanced solubility and bioavailability: Reviews highlight biosurfactant-enabled microemulsion/nanoemulsion platforms (notably with rhamnolipids and sophorolipids) as strategies to increase the solubilization of poorly water-soluble actives and broaden the formulation design space [140].

- -

- Targeted/functional delivery: Biosurfactant-containing assemblies can be co-formulated with nanoparticles or engineered with targeting ligands (conceptually similar to other surfactant-based delivery systems) to improve tissue selectivity and reduce off-target toxicity [141].

- -

- Transdermal and mucosal delivery: Surfactant-based systems are widely studied as permeation enhancers; biosurfactants are increasingly discussed within this context for topical/transdermal approaches, including microemulsion-based gels and advanced topical delivery frameworks [142].

8.3. Oncology (Anticancer Activity)

8.4. Wound Healing and Regenerative Medicine

- -

- Tissue repair effects. Bacillus-derived lipopeptides have been reported in experimental models to support wound closure outcomes and antioxidant-linked benefits, with histological improvements in some animal studies [146].

- -

- Formulation opportunities. Because chronic wounds frequently involve polymicrobial biofilms and high protease burden, biosurfactants are also attractive as components of hydrogels/films/coatings that combine antibiofilm action with a moist healing environment (an area still actively developing) [147].

8.5. Immunomodulation and Antiviral Support

8.6. Specialized Medical and Diagnostic Uses

9. Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miethke, M.; Pieroni, M.; Weber, T.; Brönstrup, M.; Hammann, P.; Halby, L.; Arimondo, P.B.; Glaser, P.; Aigle, B.; Bode, H.B.; et al. Toward the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 726–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, A.; Lemoine, P.; Simpson, A.B.J.; Murray, J.; O’Hagan, B.M.G.; Naughton, P.J.; Dooley, J.G.; Banat, I.M. Microscopic investigation of the combined use of antibiotics and biosurfactants on methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, S.M.; Kang, J.; Kim, D.H. Surfactants: Recent advances and their applications. Compos. Comm. 2020, 22, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.K.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional biomolecules of the 21st century. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banat, I.M.; Franzetti, A.; Gandolfi, I.; Bestetti, G.; Martinotti, M.G.; Fracchia, L.; Smyth, T.; Marchant, R. Microbial biosurfactants production, applications and future potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xu, J.; Xie, W.; Yao, Z.; Yang, H.; Sun, C.; Li, X. Pseudomonas aeruginosa L10: A hydrocarbon-degrading, biosurfactant-producing, and plant-growth-promoting endophytic bacterium isolated from a reed (Phragmites australis). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, F.G.; Johnson, M.J. A glycolipid produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 4124–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, P.; Spencer, J.; Tulloch, A. Hydroxy fatty acid glycosides of sophorose from Turolopsis magnoliae. Can. J. Chem. 1961, 39, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorek, E.; Pacholak, A.; Zdarta, A.; Smułek, W. The impact of biosurfactants on microbial cell properties leading to hydrocarbon bioavailability increase. Colloids Interfaces 2018, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, I.; Ghribi, D. Glycolipid biosurfactants: Main properties and potential applications in agriculture and food industry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4310–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mawgoud, A.M.; Lépine, F.; Déziel, E. Rhamnolipids: Diversity of structures, microbial origins and roles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, G.; Dhasmana, A.; Kumar, V. Biosurfactants: The next generation biomolecules for diverse applications. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 3, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.G.; Guerra, J.M.C.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Production and application prospects in the food industry. Biotechnol. Prog. 2020, 36, e3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, S.A.; Vederas, J.C. Lipopeptides from Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp.: A gold mine of antibiotic candidates. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenibo, E.O.; Ijoma, G.N.; Selvarajan, R.; Chikere, C.B. Microbial surfactants: The next generation multifunctional biomolecules for applications in the petroleum industry and its associated environmental remediation. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaric, N.; Sukan, F.V. Biosurfactants: Production, Properties and Applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sarubbo, L.A.; Silva, M.C.; Durval, I.J.B.; Bezerra, K.G.O.; Ribeiro, B.G.; Silva, I.A.; Twigg, M.S.; Banat, I.M. Biosurfactants: Production, properties, applications, trends, and general perspectives. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 181, 108377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Bryam, A.M.; Yoshimura, I.; Santos, L.P.; Moura, C.C.; Santos, C.C.; Silva, V.L.; Lovaglio, R.B.; Costa-Marques, R.F.; Jafelicci, M., Jr.; Contiero, J. Silver nanoparticles stabilized by rhamnolipids: Effect of pH. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 205, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, J.R.; Da Costa Correia, J.A.; De Almeida, J.G.L.; Rodrigues, S.; Pessoa, O.D.L.; Melo, V.M.M.; Goncalves, L.R.B. Evaluation of a co-product of biodiesel production as carbon source in the production of biosurfactant by P. aeruginosa MSIC02. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Padilha, C.E.; da Costa Nogueira, C.; de Santana Souza, D.F.; de Oliveira, J.A.; dos Santos, E.S. Valorization of green coconut fiber: Use of the black liquor of organolsolv pretreatment for ethanol production and the washing water for production of rhamnolipids by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27583. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Almeida, D.; Rufino, R.; Luna, J.; Santos, V.; Sarubbo, L. Applications of biosurfactants in the petroleum industry and the remediation of oil spills. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12523–12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Essam, T.; Yassin, A.S.; Salama, A. Optimization of rhamnolipid production by biodegrading bacterial isolates using Plackett-Burman design. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 2, 573–579. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, V.K.; Bajaj, A.; Regar, R.K.; Kamthan, M.; Jha, R.R.; Srivastava, J.K.; Manickam, N. Rhamnolipid from a Lysinibacillus sphaericus strain IITR51 and its potential application for dissolution of hydrophobic pesticides. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 272, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalini, S.; Parthasarathi, R. Optimization of rhamnolipid biosurfactant production from Serratia rubidaea SNAU02 under solid-state fermentation and its biocontrol efficacy against Fusarium wilt of eggplant. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2018, 16, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christova, N.; Lang, S.; Wray, V.; Kaloyanov, K.; Konstantinov, S.; Stoineva, I. Production, structural elucidation, and in vitro antitumor activity of trehalose lipid biosurfactant from Nocardia farcinica strain. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyukina, M.S.; Ivshina, I.B.; Baeva, T.A.; Kochina, O.A.; Gein, S.V.; Chereshnev, V.A. Trehalolipid biosurfactants from nonpathogenic Rhodococcus actinobacteria with diverse immunomodulatory activities. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.I.S.; Ribeiro, B.G.; Guerra, J.M.C.; Rufinoa, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A.; Santos, V.A.; Luna, J.M. Production in bioreactor, toxicity and stability of a low-cost biosurfactant. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 64, 595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Albuquerque, C.D.C.; Sarubbo, L.A.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. Economic optimized medium for tensio-active agent production by Candida sphaerica UCP0995 and application in the removal of hydrophobic contaminant from sand. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 2463–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Tian, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Mohsin, A.; Chu, J. Efficient sophorolipids production via a novel in situ separation technology by Starmerella bombicola. Process Biochem. 2019, 81, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, C.P.; Price, N.P.; Ray, K.J.; Kuo, T.M. Production of sophorolipid biosurfactants by multiple species of the Starmerella (Candida) bombicola yeast clade. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010, 1, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelino, P.R.F.; Peres, G.F.D.; Teran-Hilares, R.; Pagnocca, F.C.; Rosa, C.A.; Lacerda, T.M.; dos Santos, J.C.; da Silva, S.S. Biosurfactants production by yeasts using sugarcane bagasse hemicellulosic hydrolysate as new sustainable alternative for lignocellulosic biorefineries. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, M.; Xue, J.; Shi, K.; Gu, M. Characterization and enhanced degradation potentials of biosurfactant-producing bacteria isolated from a marine environment. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Tiwari, P.; Pandey, L.M. Isolation and characterization of biosurfactant producing and oil degrading Bacillus subtilis MG495086 from formation water of Assam oil reservoir and its suitability for enhanced oil recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 270, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, P.; Alam, M.Z.; Zainuddin, E.A.; Nawawi, A.W.M.F.W. Production of biosurfactant in 2L bioreactor using sludge palm oil as a substrate. IIUM Eng. J. 2011, 12, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Jin, M.; Cui, T.; Long, X. Application of biosurfactant surfactin as a pH-switchable biodemulsifier for efficient oil recovery from waste crude oil. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phulpoto, I.A.; Yu, Z.; Hu, B.; Wang, Y.; Ndayisenga, F.; Li, J.; Liang, H.; Qazi, M.A. Production and characterization of surfactin-like biosurfactant produced by novel strain Bacillus nealsonii S2MT and its potential for oil contaminated soil remediation. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Yadav, S.; Desai, A.J. Application of response-surface methodology to evaluate the optimum medium components for the enhanced production of lichenysin by Bacillus licheniformis R2. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 41, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, P.; Singh, D. Review on biosurfactant production and its application. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 4228–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Marinho, P.H.C.; Farias, C.B.B.; Ferreira, S.R.M.; Sarubbo, L.A. Removal of petroleum derivative adsorbed to soil by biosurfactant Rufisan produced by Candida lipolytica. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 109, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittgens, A.; Rosenau, F. On the road toward tailor-made rhamnolipids: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 8175–8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, P. Acinetobacter. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology, 2nd ed.; Batt, C.A., Tortorello, M.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gudina, E.J.; Rocha, V.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.R. Antimicrobial and antiadhesive properties of a biosurfactant isolated from Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei A20. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakensen, M.; Dobson, M.; Hill, J.E.; Ziola, B. Reclassification of Pediococcus dextrinicus (Coster and White 1964) Back 1978 (Approved Lists 1980) as Lactobacillus dextrinicus comb.nov. and emended description of the genus Lactobacillus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 615–621. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, A.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Setoodeh, P.; Mesbahi, G.; Yousefi, G. Biosurfactant production by lactic acid bacterium Pediococcus dextrinicus SHU1593 grown on different carbon sources: Strain screening followed by product characterization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzozowski, B.; Bednarski, W.; Golek, P. The adhesive capability of two Lactobacillus strains and physicochemical properties of their synthesized biosurfactants. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2011, 49, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fracchia, L.; Cavallo, M.; Allegrone, G.; Matinotti, M.G. A Lactobacillus-derived biosurfactant inhibits biofilm formation of human pathogenic Candida albicans biofilm producers. Curr. Res. Technol. Educ. Top. Appl. Microbiol. Microb. Biotechnol. 2010, 2, 827–837. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, I.M.C.; Cordeiro, A.L.; Teixeira, G.S.; Domingues, V.S.; Nardi, R.M.D.; Monteiro, A.S.; Alves, R.J.; Siqueira, E.P.; Santos, V.L. Biological and physicochemical properties of biosurfactants produced by Lactobacillus jensenii P6A and Lactobacillus gasseri P65. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sheshtawy, H.S.; Doheim, M.M. Selection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for biosurfactant production and study of its antimicrobial activity. Egypt. J. Pet. 2014, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalsadiq, N.; Hassan, Z.; Lani, M. Antimicrobial, anti-adhesion and anti-biofilm activity of biosurfactant isolated from Lactobacillus spp. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform. 2018, 4, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalsadiq, N.K.A.; Zaiton, H. Biosurfactant and antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from different sources of fermented foods. Asian J. Pharmaceut. Res. Dev. 2018, 6, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippolyte, M.T.; Augustin, M.; Hervé, T.M.; Robert, N.; Devappa, S. Application of response surface methodology to improve the production of antimicrobial biosurfactants by Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans N2 using sugar cane molasses as substrate. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, E.S.C.; Priya, S.S.; George, S. Isolation of biosurfactant from Lactobacillus sp. and study of its inhibitory properties against E. coli biofilm. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornea, C.P.; Roming, F.I.; Sicuia, O.A.; Voiased, C.; Zamfir, M.; Grosutudor, S.S. Biosurfactant production by Lactobacillus spp. strains isolated from Romanian traditional fermented food products. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 21, 11312–11320. [Google Scholar]

- Satpute, S.K.; Mone, N.S.; Das, P.; Banpurkar, A.G.; Banat, I.M. Lactobacillus acidophilus derived biosurfactant as a biofilm inhibitor: A promising investigation using microfluidic approach. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Saini, N.K.; Thakur, V.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. Rhamnolipid the glycolipid biosurfactant: Emerging trends and promising strategies in the field of biotechnology and biomedicine. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Fukuoka, T.; Imura, T.; Kitamoto, D. Glycolipid Biosurfactants. In Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, H.; Li, Q. Microbial production of rhamnolipids: Opportunities, challenges and strategies. Microb. Cell Factories 2017, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, A.-M.; Marchal, R.; Vandecasteele, J.-P. Sophorose lipid production from lipidic precursors: Predictive evaluation of industrial substrates. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1994, 13, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, T.; Ge, L.; Yu, F.; Zhao, M.; Xu, Q.; Jin, M.; Chen, B.; Long, X. Efficient production of biosurfactant surfactin by a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis (sp.) 50499 strain from oil-contaminated soil. Food Bioprod. Process. 2023, 142, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaraguppi, D.A.; Bagewadi, Z.K.; Patil, N.R.; Mantri, N. Iturin: A promising cyclic lipopeptide with diverse applications. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Housseiny, G.S.; Aboshanab, K.M.; Aboulwafa, M.M.; Hassouna, N.A. Structural and physicochemical characterization of rhamnolipids produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa P6. AMB Express 2020, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Chatterjee, N.; Das, A.K.; McClements, D.J.; Dhar, P. Sophorolipids: A comprehensive review on properties and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 313, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaligram, N.S.; Singhal, R.S. Surfactin—A review. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 48, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bochynek, M.; Lewińska, A.; Witwicki, M.; Dębczak, A.; Łukaszewicz, M. Formation and structural features of micelles formed by surfactin homologues. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1211319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haba, E.; Pinazo, A.; Jauregui, O.; Espuny, M.J.; Infante, M.R.; Manresa, A. Physicochemical characterization and antimicrobial properties of rhamnolipids produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 47T2 NCBIM 40044. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 81, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.I.; Gudiña, E.J.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.R. Sodium chloride effect on the aggregation behavior of rhamnolipids and their antifungal activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.A.; Faustino, C.; Guerreiro, P.S.; Frade, R.F.; Bronze, M.R.; Castro, M.F.; Ribeiro, M.H.L. Development of novel sophorolipids with improved cytotoxic activity toward MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. J. Mol. Recognit. 2015, 28, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.-H.; Liao, Z.-Y.; Wang, C.-L.; Yang, W.-Y.; Lu, M.-F. Evaluation of a lipopeptide biosurfactant from Bacillus natto TK-1 as a potential source of anti-adhesive, antimicrobial and antitumor activities. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.F.; Gudiña, E.J.; Costa, R.; Vitorino, R.; Teixeira, J.A.; Coutinho, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.R. Optimization and characterization of biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis isolates toward microbial enhanced oil recovery applications. Fuel 2013, 111, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otzen, D.E. Biosurfactants and surfactants interacting with membranes and proteins: Same but different? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2017, 1859, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, H.; Zeng, G.; Liu, G.; Yu, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; et al. Effects of rhamnolipids on microorganism characteristics and applications in composting: A review. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 200, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Ramírez, M.; Silva-Jiménez, H.; Banat, I.M.; Díaz De Rienzo, M.A. Surfactants: Physicochemical interactions with biological macromolecules. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.D.F.; Vieira, E.A.; Nitschke, M. The antibacterial activity of rhamnolipid biosurfactant is pH dependent. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenaerts, L.; Passos, T.F.; Gayán, E.; Michiels, C.W.; Nitschke, M. Hurdle technology approach to control Listeria monocytogenes using rhamnolipid biosurfactant. Foods 2023, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, T.F.; Nitschke, M. The combined effect of pH and NaCl on the susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes to rhamnolipids. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.Y.; Ng, J.F.; Yap, W.H.; Goh, B.H. Sophorolipids—Bio-based antimicrobial formulating agents for applications in food and health. Molecules 2022, 27, 5556. [Google Scholar]

- Thimon, L.; Peypoux, F.; Wallach, J.; Michel, G. Effect of the lipopeptide antibiotic, iturin A, on morphology and membrane ultrastructure of yeast cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 128, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KRÜSS GmbH. Surface Tension. Available online: https://www.kruss-scientific.com/en/know-how/glossary/surface-tension (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- dos Santos, S.C.; Torquato, C.A.; Santos, D.d.A.; Orsato, A.; Leite, K.; Serpeloni, J.M.; Losi-Guembarovski, R.; Pereira, E.R.; Dyna, A.L.; Barboza, M.G.L.; et al. Production and characterization of rhamnolipids by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in the Amazon region, and potential antiviral, antitumor, and antimicrobial activity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carra, J.B.; Wessel, K.B.B.; Pereira, G.N.; Oliveira, M.C.; Pattini, P.M.T.; Masquetti, B.L.; Amador, I.R.; Bruschi, M.L.; Casagrande, R.; Georgetti, S.R.; et al. bioadhesive polymeric films containing rhamnolipids, an innovative antimicrobial topical formulation. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2024, 25, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Hwang, B.K. In vivo control and in vitro antifungal activity of rhamnolipid B, a glycolipid antibiotic, against Phytophthora capsici and Colletotrichum orbiculare. Pest Manag. Sci. 2000, 56, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalos, A.; Pinazo, A.; Infante, M.R.; Casals, M.; García, F.; Manresa, A. Physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of new rhamnolipids produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa AT10 from soybean oil refinery wastes. Langmuir 2001, 17, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfabad, T.; Shahcheraghi, F.; Shooraj, F. Assessment of antibacterial capability of rhamnolipids produced by two indigenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2012, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.S.; Khan, M.Y.; Archana, K.; Reddy, M.G.; Hameeda, B. Utilization of mango kernel oil for the rhamnolipid production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa DR1 toward its application as biocontrol agent. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 221, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archana, K.; Reddy, K.S.; Parameshwar, J.; Bee, H. Isolation and characterization of sophorolipid producing yeast from fruit waste for application as antibacterial agent. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 2, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, V.A.I.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Junior, A.G.d.O.; Mantovani, M.S.; Nakazato, G.; Celligoi, M.A.P.C. Antimicrobial effects ofsophorolipid along with lactic acid against poultry-relevant isolates. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankulkar, R.; Chavan, M. Characterization and application studies of sophorolipid biosurfactant by Candida tropicalis RA1. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13, 1653–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Borah, S.N.; Kandimalla, R.; Bora, A.; Deka, S. Sophorolipid biosurfactant can control cutaneous dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengle-Pulate, V.; Chandorkar, P.; Bhagwat, S.; Prabhune, A.A. Antimicrobial and SEM studies of sophorolipids synthesized using lauryl alcohol. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2014, 17, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, P.; Dineshkumar, G.; Jayaseelan, T.; Deepalakshmi, K.; Kumar, C.G.; Balan, S.S. Antimicrobial activities of a promising glycolipid biosurfactant from a novel marine Staphylococcus saprophyticus SBPS 15. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Sen, R. Antimicrobial potential of a lipopeptide biosurfactant derived from a marine Bacillus circulans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ren, B.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Kokare, C.R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Song, F.; Liu, M.; et al. Production and characterization of a group of bioemulsifiers from the marine Bacillus velezensis strain H3. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1881–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadipour, M.; Mousivand, M.; Jouzani, G.S.; Abbasalizadeh, S. Molecular and biochemical characterization of Iranian surfactin-producing Bacillus subtilis isolates and evaluation of their biocontrol potential against Aspergillus flavus and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Can. J. Microbiol. 2009, 55, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Mahata, D.; Paul, D.; Korpole, S.; Franco, O.L.; Mandal, S.M. Purification, biochemical characterization and self-assembled structure of a fengycin-like antifungal peptide from Bacillus thuringiensis strain SM1. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 66994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.V.; Keharia, H. Identification of surfactins and iturins produced by potent fungal antagonist, Bacillus subtilis K1 isolated from aerial roots of banyan (Ficus benghalensis) tree using mass spectrometry. 3 Biotech 2014, 4, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, M.; Rasool, M.H.; Naqvi, S.A.R.; Waseem, M.; Aslam, B. Biosurfactants production potential of native strains of Bacillus cereus and their antimicrobial, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 31, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lu, Z.; Bie, X.; Lu, F.; Zhao, H.; Yang, S. Optimization of inactivation of endospores of Bacillus cereus by antimicrobial lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis fmbj strains using a response surface method. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Q. Antibacterial activity and mannosylerythritol lipids against vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus cereus. Food Control 2019, 106, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, C.; Salvo, M.; Cevenini, R.; Parolin, C.; Vitali, B.; Marangoni, A. Vaginal Lactobacilli reduce Neisseria gonorrhoeae viability through multiple strategies: An in vitro study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merghni, A.; Dallel, I.; Noumi, E.; Kadmi, Y.; Hentati, H.; Tobji, S.; Ben Amor, A.; Mastouri, M. Antioxidant and antiproliferative potential of biosurfactants isolated from Lactobacillus casei and their anti-biofilm effect in oral Staphylococcus aureus strains. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 104, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Biosurfactants: A sustainable replacement for chemical surfactants? Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.; Bauer, J.; Andra, J.; Schromm, A.B.; Ernst, M.; Rossle, M.; Zahringer, U.; Rademann, J.; Brandenburg, K. Biophysical characterization of synthetic rhamnolipids. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 5101–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiller, J.C.; Liao, C.J.; Lewis, K.; Klibanov, A.M. Designing surfaces that kill bacteria on contact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 5981–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, B.; Yuan, M.; Ren, S. Comparative study on antimicrobial activity of mono-rhamnolipid and di-rhamnolipid and exploration of cost-effective antimicrobial agents for agricultural applications. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.M.; Francisco, A.P.; Carvalho, F.A.; Dardouri, M.; Costa, B.; Bettencourt, A.F.; Costa, J.; Gonçalves, L.; Costa, F.; Ribeiro, I.A.; et al. aureus catheter-related infections with sophorolipids: Electing an antiadhesive strategy or a release one? Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 208, 112057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashida, J.; Nishi, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Hayashi, C.; Igarashi, M.; Takahashi, D.; Toshima, K. Systematic and stereoselective total synthesis of mannosylerythritol lipids and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 7281–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffioux, O.; Berquand, A.; Eeman, M.; Paquot, M.; Dufrêne, Y.F.; Brasseur, R.; Deleu, M. Molecular organization of surfactin-phospholipid monolayers: Effect of phospholipid chain length and polar head. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 1758–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Díaz, C.; Martín-Venegas, R.; Martínez, V.; Storniolo, C.E.; Teruel, J.A.; Aranda, F.J.; Ortiz, A.; Manresa, Á.; Ferrer, R.; Marqués, A.M. In Vitro study of the cytotoxicity and antiproliferative effects of surfactants produced by Sphingobacterium detergens. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patowary, K.; Patowary, R.; Kalita, M.C.; Deka, S. Characterization of biosurfactant produced during degradation of hydrocarbons using crude oil as sole source of carbon. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, W. Module III: Biocompatibility Testing: Cytotoxicity and Adhesion. In A Laboratory Course in Biomaterials; CRC Press-Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-López, L.; López-Prieto, A.; Lopez-Álvarez, M.; Pérez-Davila, S.; Serra, J.; González, P.; Cruz, J.M.; Moldes, A.B. Characterization and cytotoxic effect of biosurfactants obtained from different sources. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 1381–31390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentati, D.; Chebbi, A.; Hadrich, F.; Frikha, I.; Rabanal, F.; Sayadi, S.; Manresa, A.; Chamkha, M. Production, characterization and biotechnological potential of lipopeptide biosurfactants from a novel marine Bacillus stratosphericus Strain FLU5. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 167, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Saharan, B.S.; Chauhan, N.; Procha, S.; Lal, S. Isolation and functional characterization of novel biosurfactant produced by Enterococcus faecium. Springerplus 2015, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameotra, S.S.; Makkar, R.S. Recent Applications of biosurfactants as biological and immunological molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Singh, D.; Manzoor, M.; Banpurkar, A.G.; Satpute, S.K.; Sharma, D. Characterization and cytotoxicity assessment of biosurfactant derived from Lactobacillus pentosus NCIM 2912. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaridou, G.-P.; Mantso, T.; Anestopoulos, I.; Klavaris, A.; Katzastra, C.; Kiousi, D.-E.; Mantela, M.; Galanis, A.; Gardikis, K.; Banat, I.M.; et al. Toxicity profiling of biosurfactants produced by novel marine bacterial strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-S.; Ngai, S.-C.; Goh, B.-H.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H.; Chuah, L.-H. Anticancer activities of surfactin and potential application of nanotechnology assisted surfactin delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daverey, A.; Dutta, K.; Joshi, S.; Daverey, A. Sophorolipid: A glycolipid biosurfactant as a potential therapeutic agent against COVID-19. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9550–9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Gudina, E.J.; Lima, C.F.; Rodrigues, L.R. Effects of biosurfactants on the viability and proliferation of human breast cancer cells. AMB Express 2014, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Song, I.-B.; Park, B.-K.; Lim, J.-H.; Park, S.-C.; Yun, H.-I. Subacute (28 day) toxicity of Surfactin C, a lipopeptide produced by Bacillus subtilis, in rats. J. Health Sci. 2009, 55, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan-Noude, G.; Housaindokht, M.; Bazzaz, B.S. Isolation, characterization, and investigation of surface and hemolytic activities of a lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. J. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Seydlova, G.; Svobodova, J. Review of surfactin chemical properties and the potential biomedical applications. Cent. Eur. J. Med. 2008, 3, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawale, L.; Dubey, P.; Chaudhari, B.; Sarkar, D.; Prabhune, A. Anti-proliferative effect of novel primary cetyl alcohol derived Sophorolipids against human cervical cancer cells HeLa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, W.; Ma, X.; Li, J.S.; Song, X. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of sophorolipids to human cervical cancer. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 181, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formoso, S.O.; Chaleix, V.; Baccile, N.; Helary, C. Cytotoxicity evaluation of microbial sophorolipids and glucolipids using normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF) in vitro. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu, S.A.; Twigg, M.S.; Naughton, P.J.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Biosurfactants as anticancer agents: Glycolipids affect skin cells differentially dependent on chemical structure. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, B.R.; Thoendel, M.; Singh, P.K. Rhamnolipids mediate detachment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 57, 1210–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Teruel, J.A.; Espuny, M.J.; Marqués, A.; Aranda, F.J.; Manresa, A.; Ortiz, A. Modulation of the physical properties of dielaidoylphosphatidylethanolamine membranes by a dirhamnolipid biosurfactant produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Phys Lipids 2006, 142, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilge, L.; Ersig, N.; Hubel, P.; Aschern, M.; Pillai, E.; Klausmann, P.; Pfannstiel, J.; Henkel, M.; Morabbi Heravi, K.; Hausmann, R. Surfactin shows relatively low antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis and other bacterial model organisms in the absence of synergistic metabolites. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivardo, F.; Turner, R.J.; Allegrone, G.; Ceri, H.; Martinotti, M.G. Anti-adhesion activity of lipopeptide biosurfactants produced by Bacillus subtilis* against medical device-associated pathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2009, 34, 455–460. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, V.; Badia, D.; Ratsep, P. Sophorolipids having enhanced antibacterial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohl, M.; Remm, S.; Eskandarian, H.A.; Dal Molin, M.; Arnold, F.M.; Hürlimann, L.M.; Krügel, A.; Fantner, G.E.; Sander, P.; Seeger, M.A. Increased drug permeability of a stiffened mycobacterial outer membrane in cells lacking MFS transporter Rv1410 and lipoprotein LprG. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 1263–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; An, J.; Cao, T.; Guo, M.; Han, F. Application of biosurfactants in medical sciences. Molecules 2024, 29, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, M.; Duarte, N. Exploring Biosurfactants as Antimicrobial Approaches. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janek, T.; Łukaszewicz, M.; Krasowska, A. Antiadhesive activity of the biosurfactant pseudofactin II secreted by the Arctic bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens BD5. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresa, C.; Tessarolo, F.; Maniglio, D.; Tambone, E.; Carmagnola, I.; Fedeli, E.; Caola, I.; Nollo, G.; Chiono, V.; Allegrone, G.; et al. Medical-grade silicone coated with rhamnolipid R89 is effective against Staphylococcus spp. biofilms. Molecules 2019, 24, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardouri, M.; Aljnadi, I.M.; Deuermeier, J.; Santos, C.; Costa, F.; Martin, V.; Fernandes, M.H.; Gonçalves, L.; Bettencourt, A.; Gomes, P.S.; et al. Bonding antimicrobial rhamnolipids onto medical grade PDMS: A strategy to overcome multispecies vascular catheter-related infections. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 217, 112679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivardo, F.; Martinotti, M.G.; Turner, R.J.; Ceri, H. Synergistic effect of lipopeptide biosurfactants with antibiotics against mature biofilms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerk, T.R.; Severino, P.; Jain, S.; Marques, C.; Silva, A.M.; Souto, E.B. Biosurfactants: Properties and applications in drug delivery systems. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohadi, M.; Shahravan, A.; Dehghannoudeh, N.; Shafiee Ardestani, M.; Foroumadi, A. Potential use of microbial surfactants in microemulsion drug delivery systems: A Systematic Review. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.B.; Kuniyal, K.; Rawat, A.; Bisht, A.; Shah, V.; Daverey, A. Sophorolipids as anticancer agents: Progress and challenges. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, C.L.; Miceli, R.T.; Murphy, L.R.; Kingsley, D.M.; Gross, R.A.; David, T.; Corr, D.T. Sophorolipid candidates demonstrate cytotoxic efficacy against 2D and 3D breast cancer models. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Murata, T.; Ohno, A.; Yoshida, S.; Mizushima, T. Mannosylerythritol lipid is a potent inducer of apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 482–486. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Li, H.; Niu, Y.; Chen, Q. Characterization and Inducing melanoma cell apoptosis activity of mannosylerythritol lipids-a produced from Pseudozyma aphidis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, R.; Ayed, H.B.; Hmidet, N.; Béchet, M.; Jacques, P.; Nasri, M. Evaluation of dermal wound healing and antioxidant activity of biosurfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, S.; Mazumder, A.; Sriparna Datta, S.; Biswasd, D. Towards the development of an effective in vivo wound healing agent from Bacillus sp. derived biosurfactant using Catla catla fish fat. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 45515–45525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.W.; Kwon, J.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.C. Immunomodulatory role of microbial surfactants: With special emphasis on fish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.; Valeria, M.; Alessandro, P.; Lucia, L.; Antonella, C. Antiviral activity of rhamnolipid mixtures against enveloped viruses including SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2021, 13, 2121. [Google Scholar]

- Sajid, M.; Ahmad Khan, M.S.; Singh Cameotra, S.; Safar Al-Thubiani, A. Biosurfactants: Potential applications as immunomodulator drugs. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 223, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.H.; Shah, V. Guidelines for surfactant replacement therapy in neonates. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 26, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Liu, Z.; Shiina, T. Biosurfactants for Microbubble Preparation and Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, S.; Bashir, M.; Banoo, S.; Ahamed, M.I.; Anwar, N. Antitumor and anticancer activity of biosurfactant. In Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science; Inamuddin, C.O.A., Mohd, I.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 495–513. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, S.; Rameshkumar, M.R.; Nivedha, A.; Sundar, K.; Arunagirinathan, N.; Valan Arasu, M. Biosurfactants: An antiviral perspective. In Multifunctional Microbial Biosurfactants; Kumar, P., Dubey, R.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, E.; Mottahedeh, A.; McCarthy, M. The synergistic effects of rhamnolipids and antibiotics against bacteria. J. Stud. Res. 2021, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirinejad, N.; Shahriary, P.; Hassanshahian, M. Investigation of the synergistic effect of glycolipid biosurfactant produced by Shewanella algae with some antibiotics against planktonic and biofilm forms of MRSA and antibiotic resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Greenwood, A.I.; Xiong, Y.; Miceli, R.T.; Fu, R.; Anderson, K.W.; McCallum, S.A.; Mihailescu, M.; Gross, R.; Cotten, M.L. Host defense peptide piscidin and yeast-derived glycolipid exhibit synergistic antimicrobial action through concerted interactions with membranes. JACS Au 2023, 3, 3345–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, M.; Castelein, M.G.; Dewaele, C.; Roelants, S.L.K.W.; Soetaert, W.K.; Stevens, C.V. Tuning the antimicrobial activity of microbial glycolipid biosurfactants through chemical modification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1347185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maget-Dana, R.; Ptak, M. Interactions of surfactin with membrane models. Biophys. J. 1995, 68, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A.; Teruel, J.A.; Espuny, M.J.; Marqués, A.; Manresa, A.; Aranda, F.J. Effects of dirhamnolipid on the structural properties of phosphatidylcholine membranes. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 325, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, M.; Tiso, T.; Blank, L.M.; Winter, R. Interaction of rhamnolipids with model biomembranes of varying complexity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, F.J.; Teruel, J.A.; Ortiz, A. Recent advances on the interaction of glycolipid and lipopeptide biosurfactants with model and biological membranes. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 68, 101748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Charchar, P.; Separovic, F.; Reid, G.E.; Yarovsky, I.; Aguilar, M.I. The intricate link between membrane lipid structure and composition and membrane structural properties in bacterial membranes. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3408–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldes, A.B.; Rodríguez-López, L.; Rincón-Fontán, M.; López-Prieto, A.; Vecino, X.; Cruz, J.M. Synthetic and bio-derived surfactants versus microbial biosurfactants in the cosmetic industry: An overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, G.Y.; Liu, G.L.; Li, W.Z.; Yan, F. The lipopeptide 6-2 produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens anti-CA has potent activity against the biofilm-forming organisms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 108, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, S.; Katsiwela, E.; Wagner, F. Antimicrobial effects of biosurfactants. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 1989, 91, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen, C.; Ge, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, W. Chemical structure, properties and potential applications of surfactin, as well as advanced strategies for improving its microbial production. AIMS Microbiol. 2023, 9, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Sharma, V.K. Cutting-edge perspectives on biosurfactants: Implications for antimicrobial and biomedical applications. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulou, F. Incorporating AI Tools Into Downstream Process Optimization. Bioprocess Online. May 2025. Available online: https://www.bioprocessonline.com/doc/incorporating-ai-tools-into-downstream-process-optimization-0001 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Kadam, V.; Kusal, S.; Patil, S.; Singh, P. Advances and challenges in the integration of artificial intelligence in microbial biosurfactant bioprocess. AMB Express 2025, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IDBS Knowledge Base. Enhancing Process Performance with AI in Bioprocessing. May 2025. Available online: https://www.idbs.com/knowledge-base/enhancing-process-performance-with-ai-in-bioprocessing/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Pal, M.P.; Vaidya, B.K.; Desai, K.M.; Joshi, R.M.; Nene, S.N.; Kulkarni, B.D. Media optimization for biosurfactant production by Rhodococcus erythropolis: Artificial intelligence versus statistical approach. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibiotics | Resistant Microorganism(s) |

|---|---|

| Carbapenem | (−): Acinetobacter, Enterobacteriaceae |

| β-lactamase | (−): Enterobacteriaceae |

| Methicillin | (+): Staphylococcus aureus |

| Vancomycin | (+): Enterococci |

| Erythromycin | (+): Group A Streptococcus or S. pyogenes |

| Clindamycin | (+): Group B Streptococcus or S. agalactiae |

| Multidrug | (+): Clostridioides difficile, Streptococcus pneumoniae (−): Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Campylobacter, P. aeruginosa, Shigella, nontyphoidal Salmonella Yeast: Candida, Candida auris |

| Low molecular weight (<500 Da) |

| - Glycolipids: Their mono, di, tri, and tetrasaccharide types are linked to one or two fatty acid chains [11] with rhamnose and sophorose, with two major types. - Rhamnolipids: one or two fatty acid chains (8 to 16 carbons) are linked to one or two rhamnose [12]. - Sophorolipids (lactonic or acidic): Their hydrophilic disaccharide sophorose comprises two monomers connected by β-1,2 bonds [13]. - Mannosylerythritol lipids (MELs) have mannoses, linked to fatty acids. Their subdivision is based on the hydrophobic fatty acid chain length, the degree of saturation and/or acetylation [14]. - Lipopeptides: They consist of surfactin, iturin, fengycin, lichenysin, and viscosin. Over 30 types of surfactin are known [15]. - Fatty acids and phospholipids: Both bacteria and yeasts grown on n-alkanes produce phospholipids. Phospholipids have an amphipathic structure: a hydrophilic phosphate “head” attached to a glycerol backbone, which also links to two hydrophobic fatty acid “tails” |

| High molecular weight (>1000 Da) |

| - Polymeric: Emulsan (~1000 kDa) is a polyanionic amphipathic heteropolysaccharide. - Liposan (10-20 kDa, 83% carbohydrates and 17% proteins) is an emulsifier with surfactant capacity. - Alasan (~1000 kDa) [16], an anionic polysaccharide and proteins - Particulate: Macromolecules of proteins, phospholipids, polysaccharides [17], and phosphatidyl ethanolamine-rich vesicles [5]. Whole cells are represented by Cyanobacteria. |

| Biosurfactants vs. Microbial Sources |

|---|

| Glycolipids Rhamnolipds: Pseudomonas aeruginosa [19,20,21], P. cepacia [22], Pseudomonas ssp. [23], Lysinibacillus sphaericus [24], Serratia rubidaea [25] Trehalolipids: Nocardia farcinica [26], Rhodococcus sp. [27], C. bombicola [28] Sophorolipids: C. sphaerica, [29] Starmerella bombicola [30,31], Cutaneotrichosporon mucoides [32] |

| Lipopeptides Surfactin: Bacillus subtilis, B. nealsonii [33,34,35,36,37] Lichenysin: B. licheniformis [38] |

| Phospholipids Thiobacillus thiooxidans [39], K. pneumoniae [35] |

| Polymeric Surfactants Liposan: C. lipolytica [39] Rufisan; Candida species [40] Emulsan: Acinetobacter lwoffii [41] Alasan: A. radioresistens [42] |

| Biosurfactants | CMC (mg/L) | γCMC (mN/m) |

|---|---|---|

| Rhamnolipids from P. aeruginosa | ||

| - Mono [66] | 50 | 25.9 |

| - Di [66] | 15 | 33.5 |

| - Mono [67] | 25 | 25.9 |

| - Di [67] | 15 | 31.7 |

| Sophorolipids from S. bombicola [68]-diacetylated | ||

| - L-C18:0 | 29.2 | 35.7 |

| - L-C18:1 | 31.2 | 36.3 |

| - L-C18:2 | 35.0 | 38.5 |

| - L-C18:3 | 39.1 | 38.8 |

| Surfactins from B. subtilis grown on sucrose, peptone, yeast extract, and other mineral salts [69] | 250.0 | 27.9 |

| Surfactins [70] B. subtilis grown on a mineral salt solution with: | ||

| - Glucose | 325.1 | 29.2 |

| - Glycerol | 154.1 | 29.7 |

| - Lactose | 65.3 | 30.7 |

| Iturin [61] B. subtilis isolated from crude oil samples | 40 | 29 |

| mBS and Microbial Sources | Target Microorganism(s) and MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Rhamnolipids | |

| P. aeruginosa BM02 [80] | S. aureus and E. faecium (50) |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 [81] | Cutibacterium acnes (15.62); MBC (31.25) |

| P. aeruginosa B5 [82] | P. capsici (10); C. cucumerinum, C. orbiculare (25); C. destructans |

| P. aeruginosa 47T2 [68] | Gram-negative: K. pneumoniae (0.5), E. aerogenes (4), S. marcescens (8), A. faecalis (64), E. coli (64), B. bronchiseptica (128), S. typhimurium (128), P. aeruginosa (256) Gram-positive: B. subtilis (16), S. aureus (32), S. epidermidis (32) M. luteus (64), A. oxidans (128), M. phlei (128), C. perfringens (128). |

| P. aeruginosa AT10 [83] | Gram-negative: S. marcescens (16), A. faecalis (32), E. coli (32), B. bronchiseptica (128), S. typhimurium (128) Gram-positive: S. epidermidis (8), A. oxidans (16), M. phlei (16), M. luteus (32), B. subtilis (64), S. faecalis (64), S. aureus (128) |

| P. aeruginosa MR01 Diffusion test [84] | Zone of inhibition (ZOI) diameter (mm), based on 0.3 mg of biosurfactant E. coli and P. aeruginosa (no affected), B. cereus (30 mm), S. epidermidis (15 mm), S. aureus (14 mm) |

| P. aeruginosa DR1 Diffusion test [85] | Mycelial growth inhibition: M. phaseolina (60.46%, 9 μg), F. oxysporium (55%, 12 μg), P. nicotianae (63.63%, 13.5 μg) |

| Soropholipids Candida sp. AH62 [86] S. bombicola [87] C. tropicalis RA1 [88] R. babjevae YS3 [89] | S. aureus (1), B. subtilis (2), E. coli, and P. aeruginosa (4) S. aureus (31.25), L. monocytogenes (62.50). S. aureus (250), L. monocytogenes (500), E. coli (1000) T. mentgrophytes (1 mg/mL, 62% of inhibition); (4 mg/mL, 100% of inhibition) |

| C. bombicola ATCC 22214 [90] Microdilution | % Cell survival at the biosurfactant concentration (μg/mL) B. subtilis: 91.04% (0.6), 57.41% (0.8), 5.25% (1.0) P. aeruginosa: 8.77% (1), 2.19% (3), 0.31% (5) S. aureus: 9.62% (6), 1.03% (8), 0.34% (10) E. coli: 58.01% (10), 34.09% (20), 2.05% (30) C. albicans: 10.34% (25), 10.34% (50), 6.89% (75) |

| mBS and Microbial Sources | Target Microorganism(s) |

| Glycolipids S. saprophyticus SBPS 15 Diffusion test [91] | ZOI (mm) at a given surfactant concentration. Several bacteria were affected, using 0.2–3.2 μg/mL or 1.6–2.4 μg. The zone of inhibition diameter ranges from 15 to 23 mm. |

| Surfactins B. circulans [92] | Diffusion test: ZOI diameter (mm) ranges from 10.66 to 17 mm using 1000 μg/mL of surfactins against various bacteria Microdilution, MIC (μg/mL): M. flavus (200), B. pumilis (30), M. smegmatis (50), E. coli (40), S. marcescens (30), P. vulgaris (10), A. faecalis (10), and K. aerogenes (80) |

| B. velezensis H3 [93] | Diffusion test, zones of inhibition diameter (mm) at 1000 μg/mL of biosurfactant: K. peneumoniae (10 mm), S. aureus (11 mm), C. albicans (14 mm), and P. aeruginosa (14 mm) |

| B. subtilis [94] | Diffusion test, percentage of growth inhibition of A. flavus (%) at a given concentration of surfactins (mg/L): 36% (20), 54% (40), 84% (80), 100% (160) |

| Fengycin B. thuringiensis [95] | Microdilution, MIC (μg/mL) C. albicans, A. niger (15.62); S. epidermidis, E. coli (1000) |

| Iturins B. subtilis K1 [96] | Microdilution, MIC(μg/mL) A. niger and A. brunsii (2.5) |

| Lipopeptide B. cereus [97] | - Diffusion test: Zones of inhibition (mm in diameter) range from 11.4 to 20.2 mm with 30 mg/mL of biosurfactant against A. flavus, C. albicans, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and E. coli, - Microdilution, MIC (mg/mL) ranges from 0.5 to 7.6 against S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, C. albicans, and A. flavus. |

| Surfactins and Fengycin B. subtilis fmbj [98] | MIC (μg/mL): B. cereus (156.25). |

| Mannosylerythritol lipids (MELs) [99] | MELs produced by P. aphidis show antimicrobial properties at an MIC = 1.25 mg/mL against B. cereus, and the antibacterial effect is correlated with the MEL concentration. |

| mBSs produced by human-associated bacteria | - Biosurfactants from Lactobacilli have an antimicrobial effect against Neisseria gonorrhoeae [100], E. coli, S. saprophyticus, E. aerogenes, and K. pneumoniae, and antifungal activity against C. albicans [48]. - Cell-free BS of L. paracasei ssp. paracasei A20 exhibits antimicrobial and antiadhesive activities against several bacteria and fungi [43] - L. acidophilus, L. pentosus, and L. fermentum produce cell-free BSs with an antimicrobial activity [50,51]. - Pediococcus dextrinicus SHU1593 (re-classified as Lactobacillus) [44] produces cell-bound lipoprotein against B. cereus, E. aerogenes, and S. typhimurium [45]. - Cell-associated BSs produced by L. casei LBI and L. casei ATCC 393 prevent oral diseases with antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities against Staphylococcus aureus [101]. - P. aeruginosa ATCC 10145 produces a cell-free rhamnolipid BS with antimicrobial and antifungal activities [49]. |

| Biosurfactants and Microbial Sources | Conc. (g/L) | Viability (%)-Toxicity Scale (0–5) |

|---|---|---|

| L pentosus (BS5), amphoteric, lipopeptides [112] | 1 | 91-Zero |

| L pentosus (BS5), amphoteric, lipopeptides [112] | 1 | 80-2 (Moderate) |

| L. pentosus (BS5), amphoteric, a mixture of lipopeptides and glycolipids [112] | 1 | 96 (Zero) |

| L. pentosus (BS5), non-ionic, lipopeptides [112] | 1 | 97-Zero |

| L. pentosus (BS5), non-ionic, cell-bound biosurfactant, glycoprotein or glycolipopeptides [112] | 1 | 113 |

| Lipopeptide from Bacillus cereus [97] | 10 | 63-2 (Moderate) |

| Lipopeptide from B. stratosphericus [113] | 1 | 96-Zero |

| Glycolipid from Enterococcus faecium [114] is cell-compatible with mouse fibroblast cells | 6.25 | 90-Zero |

| Glycolipid from Cyberlindnera saturnus [115] | 1 | 70-2 (Moderate) |

| Cell-associated biosurfactant of L. pentosus NCIM 2912 [116] | 0.5 | - Human embryonic kidney (HEK 293): 90.3 ± 0.1% - Mouse fibroblast ATCC L929: 99.2 ± 0.43% - Human epithelial type (HEP-2): 94.3 ± 0.2% |

| Biosurfactants produced by Marinobacter strain MCTG107b and Pseudomonas strain MCTG214(3b1) [117] | O.25-3 | HaCaT cells and THLE cells - Negligible cytotoxicity up to 0.25 g/L - Viability is lower than 50% at 1 g/L |

| Biosurfactant | Antibiotic | Target Microorganism | Key Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhamnolipids | Ciprofloxacin | P. aeruginosa (biofilm) | MIC of ciprofloxacin reduced 4–8×; >90% biofilm disruption | [128] |

| Rhamnolipids | Tetracycline | S. aureus (MRSA) | Synergistic killing; enhanced membrane permeabilization | [129] |

| Surfactin | Ampicillin | E. coli | MIC reduced ~4×; membrane destabilization confirmed by SEM | [130] |

| Surfactin | Vancomycin | S. epidermidis (biofilm) | Biofilm biomass reduced >80% compared to antibiotic alone | [131] |

| Sophorolipids | Gentamicin | Candida albicans (mixed biofilm) | Significant reduction in CFU and biofilm thickness | [132] |

| R5Lipopeptide (Bacillus sp.) | Rifampicin | M. smegmatis | Enhanced intracellular drug uptake; lowered MIC | [133] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Luong, A.D.; Moorthy, M.; Luong, J.H. Microbial Biosurfactants: Antimicrobial Agents Against Pathogens. Macromol 2026, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol6010006

Luong AD, Moorthy M, Luong JH. Microbial Biosurfactants: Antimicrobial Agents Against Pathogens. Macromol. 2026; 6(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol6010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuong, Albert D., Maruthapandi Moorthy, and John HT Luong. 2026. "Microbial Biosurfactants: Antimicrobial Agents Against Pathogens" Macromol 6, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol6010006

APA StyleLuong, A. D., Moorthy, M., & Luong, J. H. (2026). Microbial Biosurfactants: Antimicrobial Agents Against Pathogens. Macromol, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol6010006