1. Introduction

Tourism has always been closely tied to the environment, influencing and being influenced by it (

McKercher, 1993;

Mikayilov et al., 2019). As a result, managing its environmental impact has been a priority for policymakers given that tourism activities can lead to significant and sometimes irreversible ecological and cultural consequences (

Tejedo et al., 2022). Heritage villages, as a distinctive form of rural tourism, have consistently faced numerous challenges in this context. Heritage villages, as defined in this study, refer to authentic rural communities that retain their original residents and traditional way of life while possessing significant cultural, architectural, and historical value, distinguishing them from constructed heritage sites or open-air museums where buildings are collected and relocated (

E. Park et al., 2019). These villages represent living heritage, where contemporary community life continues alongside the preservation of traditional practices and the built environment, constituting complex socio-ecological systems where environmental conservation imperatives interact dynamically with cultural preservation objectives and community development needs. These unique tourism destinations showcase distinctive cultural landscapes and historical importance through their authentic architecture, traditional crafts, indigenous knowledge systems, and intergenerational cultural transmission processes, embodying centuries of traditions and historical significance within their physical structures, community practices, and social fabric (

Torabi et al., 2024). While heritage villages attract visitors seeking authentic cultural experiences and play a crucial role in preserving cultural traditions and historical landscapes, these delicate socio-ecological environments increasingly face mounting pressure from tourism development, particularly from overdevelopment, the excessive use of natural resources, cultural commodification, and environmental degradation caused by mass tourism phenomena (

P. Zhang & Cao, 2023). To protect these valuable cultural and environmental assets, comprehensive collaboration among all stakeholders—including tourists, tourism operators, local communities, and heritage management authorities—is essential through implementing sustainable tourism practices such as reducing waste generation, utilizing resources judiciously, promoting environmentally responsible transportation options, and fostering cultural sensitivity among visitors (

Aznar & Hoefnagels, 2019;

Zhuang et al., 2019). The increasing emphasis on sustainable tourism in heritage villages has drawn considerable attention from researchers and practitioners due to its multifaceted benefits, as sustainable tourism approaches help preserve cultural and historical heritage while simultaneously creating economic opportunities for local communities and supporting environmental conservation initiatives (

MacInnes et al., 2022). Consequently, understanding and promoting environmentally responsible behavior among tourists within heritage villages is of paramount importance due to its direct impact on the long-term ecological viability, cultural authenticity, and socioeconomic sustainability of these distinctive destinations (

Torabi et al., 2024).

Understanding and promoting environmentally responsible behavior among tourists have become key considerations in ensuring the sustainability of destinations (

Su et al., 2020). Research indicates a strong connection between tourists’ intentions to act responsibly towards the environment and their actual behaviors (

Sarmento & Loureiro, 2021). The challenge is to connect environmental awareness and actual behavioral change, making it essential to develop comprehensive strategies that encourage and facilitate responsible tourism practices.

To comprehend and influence tourist behavior, the TPB offers a valuable framework (

Ajzen, 2020). The TPB suggests that what someone plans to do is the most important factor in predicting whether they will actually do it (

Ajzen, 1991). The TPB has been validated in various tourism contexts, demonstrating its value in explaining tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors and intentions (

Rao et al., 2022). Researchers have extensively used the TPB to investigate and forecast environmentally responsible actions among tourists, acknowledging its strong analytical approach to explaining how people’s attitudes translate into real-world conduct (

J. Cao et al., 2023;

Chen & Tung, 2014;

Yayla et al., 2021). This theoretical framework has proven particularly valuable in tourism contexts because it acknowledges that responsible behavior is influenced not only by personal attitudes (

Qiu et al., 2022) but also by social norms (

Chen & Tung, 2014) and perceived behavioral control elements (

Ji et al., 2024) that are especially relevant in tourist settings where visitors must navigate unfamiliar environments and social expectations. Recent research has advanced our understanding of tourists’ responsible behavior through studies of environmental awareness, social pressure, and perceived barriers (

Chiu et al., 2014;

Su & Swanson, 2017). The TPB has served as a valuable framework in tourism research, though its application has largely focused on social environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Despite the extensive application of TPB in tourism research, few studies have attempted to understand how tourists’ emotional and psychological connections to places influence their environmental behavior, particularly in rural heritage tourism settings (

Brehm et al., 2013;

Ramkissoon et al., 2013). This study aims to address this gap by examining how place-based psychological connections interact with the TPB to shape environmentally responsible behavior in heritage villages, providing a deeper insight into tourist behavior in these distinctive locations. The bond between tourists and destinations involves two essential psychological concepts: place attachment and place identity (

Dini et al., 2023).

Place attachment captures the personal and emotional significance people associate with certain spaces or settings (

Brehm et al., 2013). It is a multidimensional construct that encompasses the feelings of belonging, emotional connections, and sense of identity individuals associate with a place (

Daryanto & Song, 2021). People with a strong place attachment often exhibit a greater willingness to protect and preserve the environment and cultural heritage of those places (

Anton & Lawrence, 2016). Furthermore, place identity represents a specific aspect of place attachment, where a location becomes an integral part of a person’s understanding of themselves (

Wan et al., 2022). It involves the meanings, feelings, and values individuals associate with a place that contribute to their sense of self. People who have a deep connection to a specific location tend to be more inclined to engage in behaviors that protect its unique characteristics and cultural significance (

T.-M. Cheng et al., 2012;

Tonge et al., 2015).

While existing studies have extensively explored the influence of TPB factors on tourist behavior, the role of place attachment and place identity, as emotional and psychological drivers of environmentally responsible behavior, remains less understood (

Ramkissoon et al., 2012). Prior research has often treated these constructs in isolation or has not fully integrated them within the TPB framework. Therefore, by exploring the intricate interplay between place connections and personal identity, this research aims to enrich our understanding of the TPB within the unique landscape of heritage villages.

A systematic examination of the extant literature reveals three significant research gaps concerning environmentally responsible behavior in heritage tourism contexts. First, while the TPB has been extensively employed to examine environmental behavior across diverse tourism settings (

Lee & Lina Kim, 2018), its application specifically within heritage village contexts remains notably limited. This theoretical gap is particularly pronounced given the distinctive characteristics of heritage destinations, where the convergence of ecological sensitivity and cultural significance potentially alters the manifestation of attitudinal, normative, and control factors in environmental behavior formation (

Cai & Cheng, 2024). Second, despite mounting empirical evidence supporting the critical role of place-related psychological constructs in conservation behaviors across various environmental contexts (

Brehm et al., 2013), no investigation has systematically examined the specific moderating function of place identity and the mediating role of place attachment within the TPB framework as applied to heritage villages. This conceptual oversight represents a significant limitation in our current understanding, particularly given the profound place-based connections that characterize heritage tourism experiences (

Barr et al., 2011). Third, the methodological approaches in existing environmental behavior studies have predominantly employed unidimensional frameworks, with the absence of intricate connections between psychological factors and place-based influences that drive environmental actions (

Fielding et al., 2008). This methodological limitation is particularly evident in research conducted within the Iranian context, where investigations have primarily focused on descriptive analyses of environmental behaviors rather than explanatory frameworks that illuminate the underlying psychological and spatial mechanisms. The present study addresses these theoretical, conceptual, and methodological gaps by developing and empirically validating an integrated framework that synthesizes the TPB with place-related constructs, thereby advancing understanding of the complex determinants of environmentally responsible behavior in heritage tourism contexts.

2. The Theoretical Framework and a Literature Review

Heritage villages represent complex socio-ecological–cultural systems where authentic rural communities maintain their traditional way of life while navigating the tensions between cultural preservation, tourism development, and evolving community values. These living heritage destinations are characterized not only by their physical attributes but also by the dynamic cultural values that resident communities attach to place, values that may evolve through intergenerational transmission while maintaining core cultural identity elements (

Katapidi, 2021;

Mazzetto, 2023). These distinctive destinations, characterized by their intricate cultural landscapes and environmental significance, face intensifying pressures from increasing tourist volumes and associated activity patterns (

Mohammadi et al., 2022;

Perkins et al., 2023). The fundamental paradox within heritage tourism contexts stems from tourism’s dual role as both an economic catalyst for rural development and a potential environmental stressor, manifesting through resource consumption intensification, waste generation acceleration, and the potential degradation of cultural authenticity (

Altassan, 2023;

Lu & Ahmad, 2023). This inherent tension necessitates the development of sophisticated theoretical frameworks capable of capturing the complex behavioral mechanisms underlying environmentally responsible actions in these culturally significant settings (

Ghaderi et al., 2018;

Timothy & Boyd, 2006). The analytical approach must acknowledge the distinctive characteristics of heritage destinations, where environmental behaviors acquire heightened significance due to their implications for both ecological sustainability and cultural preservation (

Torabi et al., 2024;

Yanan et al., 2024).

The TPB has demonstrated considerable utility as a foundational framework for analyzing environmental behavior formation in tourism contexts, delineating the systematic interaction between attitudinal dispositions, normative influences, and perceived behavioral control as determinants of behavioral intentions and subsequent actions (

Ulker-Demirel & Ciftci, 2020). However, contemporary scholarly discourse increasingly recognizes that the traditional behavioral models may inadequately capture the complete spectrum of factors influencing environmental decision-making in heritage tourism settings, particularly regarding place-based psychological connections (

Massara & Severino, 2013;

H. Zhang et al., 2023). While the TPB provides robust explanations of cognitive-evaluative processes, it offers limited conceptualization of how emotional and identity-based connections to specific environments influence behavioral outcomes (

Hinds & Sparks, 2008). Recent empirical investigations suggest that integrating place-related psychological constructs, specifically place identity and place attachment, with the TPB substantially enhances the explanatory power and theoretical sophistication when examining environmental behaviors in heritage contexts (

Osiako & Szente, 2024;

Shen & Shen, 2021). This theoretical integration acknowledges that tourists’ psychological and emotional connections to heritage sites constitute significant determinants of environmental decision-making processes that extend beyond the traditional socio-cognitive predictors typically examined in tourism behavior research.

The integrated theoretical framework proposed in this investigation advances the scholarship on environmental behavior through a systematic synthesis of the TPB with place-related constructs, conceptualizing the place variables not merely as supplementary factors but as fundamental dimensions of the self-concept that systematically influence the traditional TPB components through identity-congruent information processing, selective attention to environmental cues, and identity-consistent behavioral standards. This approach enables a sophisticated analysis of how place identity moderates the intention–behavior relationship, addressing critical gaps in understanding the complex interplay between psychological connections to heritage sites and the established TPB determinants (

Zhu et al., 2022). The theoretical synthesis offers three significant contributions to the research on environmental behavior within heritage tourism contexts: (1) an extension of the TPB through the incorporation of spatial–psychological dimensions previously underexplored in heritage settings, (2) the development of a more comprehensive analytical framework capturing the multidimensional nature of environmental behavior formation, and (3) illumination of the complex interaction patterns between psychological and spatial factors that shape sustainable tourism practices in heritage contexts. This multifaceted approach provides a more nuanced theoretical foundation for developing effective environmental management strategies in heritage tourism destinations, with significant implications for balancing conservation priorities with development objectives (

C. Park et al., 2022;

Shen & Shen, 2021).

To explore the factors influencing tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior in heritage villages, this study adopts the TPB as its guiding theoretical framework (

X. Li & Romainoor, 2024). The TPB is a widely used social–cognitive model for predicting and explaining human behavior in specific contexts (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2019;

Wan et al., 2022). Building upon the theory of reasoned action, the TPB has been extensively applied to understanding the determinants of a range of social behaviors, including pro-environmental behaviors (

J. Cao et al., 2023). A key concept in the TPB is that the intention to perform a behavior is the most direct indicator of whether that behavior will actually occur (

Duarte Alonso et al., 2015;

Wan et al., 2022). According to

Fielding et al. (

2008), in the TPB, a person’s strong intention to perform a behavior is influenced by three key factors: their positive attitudes toward the behavior, the support they receive from significant others due to engaging in the behavior, and their belief that they have the ability to carry out the behavior. The theory suggests that intention is the immediate precursor to behavior, and it is shaped by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. This intention is shaped by three key determinants. Environmentally responsible behaviors in heritage destinations have emerged as a critical component of environmental sustainability (

Elshaer et al., 2024). Understanding the factors influencing responsible and sustainable environmental behaviors, particularly among tourists, is essential for promoting conservation practices in these sensitive areas (

Z. Cheng & Chen, 2022). The TPB has been widely used to study how attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control influence environmental behaviors (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2019;

Zhao et al., 2020). Previous studies have highlighted the significant impact of environmental attitudes on tourists’ behavioral intentions (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2019). When tourists comprehend the positive consequences of environmental behaviors, they tend to demonstrate such behaviors during their travel experiences (

Buonincontri et al., 2017). Conversely, awareness of the negative implications of irresponsible behaviors may deter tourists from disregarding environmental concerns (

Torabi et al., 2024). Environmental norms have been identified as a vital factor in shaping and reinforcing tourists’ ethical behaviors (

Fenitra et al., 2022;

Wasaya et al., 2024). When tourists notice themselves as environmentally responsible agents, their adherence to environmental norms tends to increase (

C. Park et al., 2022). This understanding emphasizes the importance of strengthening social norms and establishing expectations for tourists as ethical agents in environmental conservation within heritage regions. Perceived behavioral control is acknowledged as a direct factor influencing tourists’ behavioral intentions (

Rao et al., 2022). The perception that individual actions will lead to positive outcomes, such as rewards for environmental behaviors, encourages this group to adhere to norms in their tourism behaviors (

S. Wang et al., 2023). These rewards may encompass increased motivation, pride, or other significant benefits. Studies have shown that behavioral intention is a significant predictor of actual behavior (

Lin et al., 2022;

Tang et al., 2021). When tourists possess strong intentions to engage in environmental behaviors, they are more likely to manifest these behaviors in practice (

J. Li et al., 2022). This connection has been repeatedly confirmed through various studies in the sustainable tourism settings. Building on the previously discussed literature, this study proposes four hypotheses for exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intentions on tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviors in heritage destinations. Through investigating the interactions and reciprocal influences of these variables, this research attempts to enhance our understanding of how individual and social ethical norms regarding sustainable environmental behaviors are developed and strengthened among tourists. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

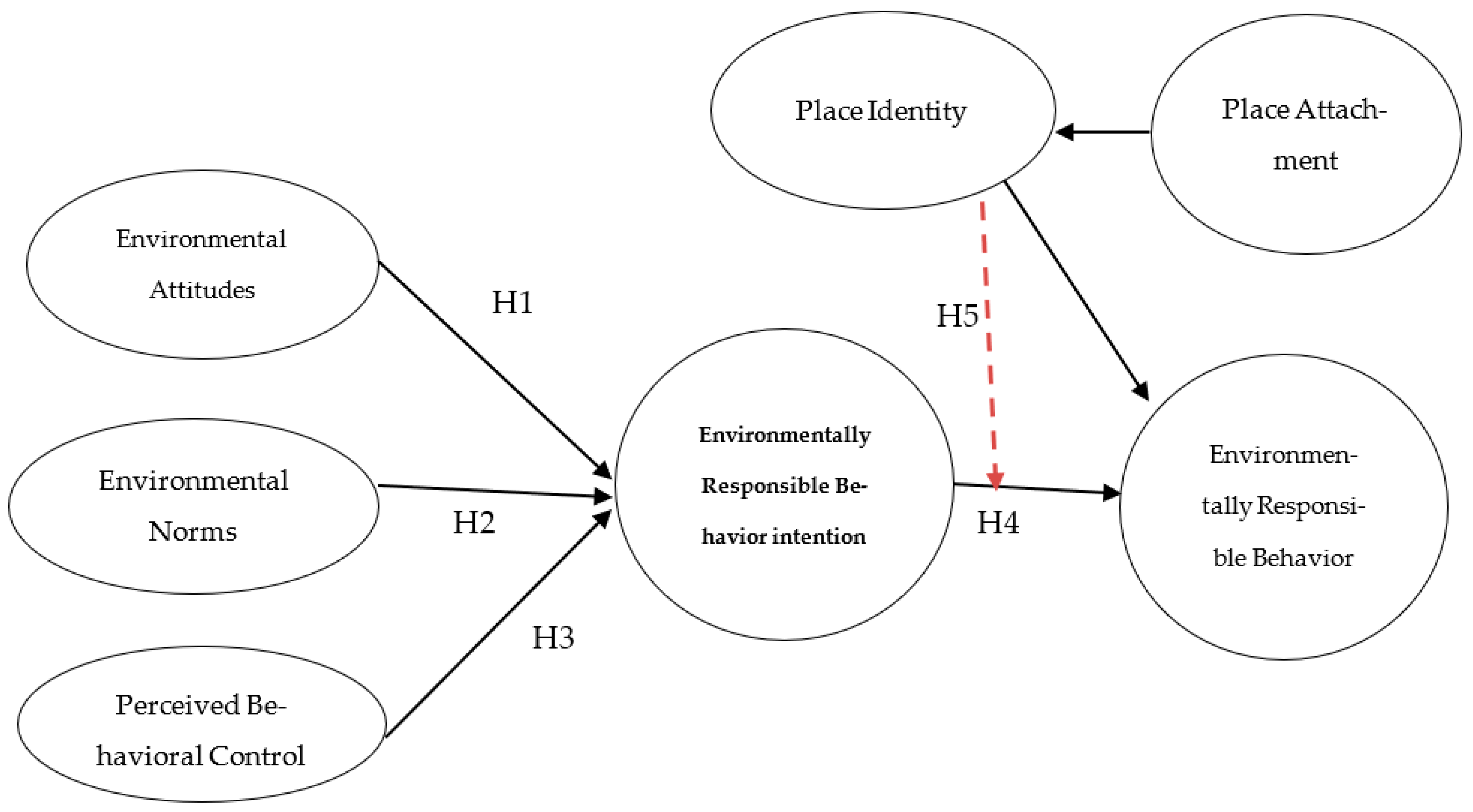

H1. Environmental attitudes have a significant positive effect on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

H2. Environmental norms have a significant positive effect on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

H3. Perceived behavioral control has a significant positive effect on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

H4. Environmentally responsible behavioral intentions have a significant positive effect on tourists’ actual behavior.

The TPB has served as a foundational framework for comprehending environmentally responsible behaviors in tourism contexts, yet its explanatory scope encounters significant limitations when applied to culturally significant destinations such as heritage villages (

Buonincontri et al., 2017;

Pourtaheri et al., 2024). Contemporary empirical evidence increasingly suggests that while the TPB allows for robust analysis of the cognitive–evaluative processes underlying environmental behaviors, it inadequately captures the complex psychological connections tourists develop with heritage landscapes (

Shen & Shen, 2021). This theoretical gap has prompted scholars to integrate place-related psychological constructs within established behavioral frameworks to enhance explanatory power. Particularly compelling is the empirical evidence from

X. Cao et al. (

2022), which revealed that place identity plays a significant moderating role in the relationship between perceived behavioral control and recycling intentions in heritage contexts. Similarly,

Ramkissoon et al. (

2012) documented a direct positive relationship between place identity and pro-environmental behavioral intentions among national park visitors, suggesting that self-place connections systematically strengthen conservation commitments. These empirical findings collectively indicate that place-based psychological processes represent not merely supplementary variables but fundamental mechanisms through which environmental behaviors develop in heritage settings—a theoretical proposition inadequately addressed in conventional TPB applications.

The relationship between place attachment and environmental behavior represents a particularly nuanced theoretical domain requiring sophisticated conceptual frameworks (

Shen & Shen, 2021). The meta-analytical findings by

Daryanto et al. (

2020) established a strong and positive association between place attachment and pro-environmental behaviors while identifying critical moderating factors including cultural context and measurement specificity. This relationship appears to operate through complex psychological pathways, with empirical evidence from

Daryanto and Song (

2021) identifying place attachment’s substantial direct effect on environmentally responsible behaviors. However, theoretical tensions emerge in the contradictory findings from

Junot et al. (

2018), who observed negative relationships between localized place identity and general environmental behaviors, suggesting important contextual boundary conditions in place–behavior relationships. This theoretical contradiction potentially reflects the distinction between site-specific conservation behaviors and generalized environmental actions, indicating differentiated psychological mechanisms underlying each behavioral category. The intermediary role of place identity in the attachment–behavior relationship documented by multiple studies (

T.-M. Cheng et al., 2012;

Yang et al., 2022) provides a coherent theoretical framework for understanding how emotional connections to heritage sites manifest in conservation behaviors through identity internalization processes.

T.-M. Cheng et al.’s (

2012) empirical verification of attachment–behavior pathways further validates this theoretical proposition, establishing place identity as a critical intervening variable in the complex psychological processes connecting spatial attachment and environmental behavior formation in heritage tourism contexts.

H5. Place identity moderates the relationship between environmentally responsible behavioral intentions and tourists’ actual behavior.

H6. Place identity mediates the relationship between place attachment and tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior.

The Conceptual Research Model

This investigation develops and empirically validates a dual-framework approach to examining environmentally responsible behavior in heritage tourism contexts, advancing our theoretical understanding through the systematic integration of psychological and spatial determinants. The foundational model operationalizes the TPB by examining the relationships between environmental attitudes, environmental norms, and perceived behavioral control as antecedents to behavioral intentions, which subsequently influence environmental behavior. This baseline framework, well-established in the environmental psychology literature, provides methodological consistency with the previous research while enabling a comparative analysis of the theoretical extension mechanisms. The extended model significantly advances our theoretical understanding by incorporating place-related variables through two distinct pathways: (1) a moderating mechanism wherein place identity influences the intention–behavior relationship, potentially strengthening the translation of intentions into observable conservation behaviors, and (2) a mediating pathway through which place attachment affects environmental behavior via place identity formation processes, illuminating the psychological mechanisms through which emotional connections to heritage sites manifest in conservation behaviors.

The integrated framework responds to critical gaps in the literature on sustainable tourism by enabling a systematic examination of both the direct effects and complex interaction patterns between psychological and spatial variables in environmental behavior formation. This sophisticated theoretical integration acknowledges the multidimensional nature of place–behavior relationships while addressing recent scholarly calls for a more nuanced understanding of the spatial–psychological connections in heritage tourism contexts. A comparative analysis of these frameworks provides empirical evidence regarding the complementary role of place-related variables in enhancing the traditional behavioral theories, with the extended model demonstrating superior explanatory power and predictive capability compared to those of the baseline TPB framework. The systematic investigation of variable interactions and behavioral pathways illuminates the intricate interaction of individual psychological mechanisms and place-based connections, offering a more comprehensive theoretical foundation for understanding and promoting sustainable behaviors in heritage tourism contexts. This theoretical advancement carries significant implications for both scholarly understanding of environmental behavior formation and practical applications in heritage tourism management, potentially informing more effective strategies for promoting conservation behaviors in these culturally significant destinations (

Figure 1).

3. Methodology

This study utilized Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) as its primary analytical approach, aligning methodologically with the study’s three central objectives: examining the TPB’s applicability in heritage tourism contexts, investigating the spatial–psychological variable integration, and analyzing place-related factors’ moderating and mediating effects. The methodological rationale for selecting PLS-SEM was predicated on four key considerations that collectively enhanced the analytical rigor: (1) its superior predictive capability for understanding how place-related factors amplify the traditional behavioral models’ explanatory power; (2) its demonstrated capacity to analyze complex theoretical frameworks incorporating multiple mediating and moderating relationships, enabling comprehensive examination of the intricate pathways connecting place attachment, place identity, and environmental behaviors; (3) its methodological robustness when handling non-normal data distributions and relatively modest sample sizes (n = 443), a particularly salient consideration given the specialized nature of heritage village tourism contexts; and (4) its analytical flexibility in simultaneously accommodating both reflective and formative measurement models, essential for examining multidimensional theoretical constructs such as place attachment and place identity, which often manifest through complex hierarchical structures in tourism research contexts. The methodological framework was operationalized through SmartPLS software (version 4), implementing a systematic two-stage analytical procedure that first assessed the validity of the measurement model before proceeding to structural model evaluation and hypothesis testing through bootstrapping procedures (5000 resamples), ensuring the validity of the statistical conclusions while maintaining analytical transparency.

3.1. The Measurement Scale and Questionnaire Design

This investigation developed a comprehensive measurement framework to examine the integration of the TPB with place-related factors in heritage tourism contexts, incorporating both established scales and context-specific items to ensure theoretical consistency while maintaining contextual relevance. The instrument operationalized seven primary theoretical constructs through reflective indicators: environmental attitudes, environmental norms, perceived behavioral control, environmentally responsible behavioral intentions, place identity, place attachment, and environmentally responsible behavior. These constructs were assessed using multi-item scales derived from the well-established literature in environmental psychology and sustainable tourism (

T.-M. Cheng et al., 2012); with systematic modifications to enhance the construct validity and reliability within the specific context of Iranian heritage village tourism. Particularly noteworthy was the adaptation process for place-related constructs, wherein established Western-developed scales underwent systematic cultural contextualization to ensure measurement equivalence while capturing the distinctive place-based connections that characterize heritage tourism experiences. This adaptation process involved collaborative examination by tourism scholars and heritage management experts to ensure both theoretical fidelity and contextual appropriateness, resulting in a measurement instrument capable of capturing the multidimensional nature of environmental behavior formation in heritage tourism settings.

The operationalization of environmentally responsible behavior—the primary dependent variable—employed a carefully developed four-item scale examining tourists’ participation in conservation activities during heritage village visits, with specific items addressing waste management practices, resource conservation behaviors, environmental advocacy, and adherence to designated protection guidelines. The measurement approach implemented systematic methodological controls to enhance the validity and reliability while mitigating potential measurement errors, including (1) the utilization of an established five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to ensure the precision of the measurements while maintaining response accessibility; (2) the implementation of procedural remedies to mitigate common method bias, including respondent anonymity guarantees, balanced item sequencing, and the incorporation of reverse-coded items; (3) rigorous instrument validation through expert review involving five tourism scholars and ten heritage tourism practitioners; and (4) a preliminary scale assessment through pilot testing with 30 heritage village visitors in June 2024, resulting in minor linguistic refinements to enhance its clarity and cultural appropriateness. This systematic approach to the development of the measurements ensures methodological rigor while maintaining contextual relevance, providing a robust foundation for examining the complex interrelationships between psychological and spatial variables in environmental behavior formation within heritage tourism settings (

Table 1).

The implementation of rigorous methodological controls addressing social desirability bias represents a critical dimension of measurement validity in environmental behavior research, particularly within heritage tourism contexts, where normative expectations may significantly influence self-reported conservation behaviors. The present investigation employed a multifaceted approach to mitigating these potential measurement artifacts through a strategic questionnaire design incorporating indirect questioning techniques, counterbalanced item valence, and enhanced anonymity protocols. Additionally, the research methodology incorporated the abbreviated Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (

Ballard, 1992) as a statistical control variable, enabling systematic assessment of response patterns potentially influenced by impression management tendencies. The observed correlation between self-reported behaviors and structured observational data (r = 0.73,

p < 0.01) provides empirical validation of the measurements’ integrity, substantiating the methodological robustness of the behavioral assessment framework.

Despite these comprehensive methodological controls, it remains essential to acknowledge the inherent limitations of self-reported behavioral measures, particularly within environmentally focused research domains where social norms strongly favor conservation-oriented responses. The potential influence of unconscious response biases, even with methodological safeguards in place, necessitates interpretive caution regarding the absolute magnitude of the reported behaviors, though the relative relationships between theoretical constructs likely maintain their validity given the consistent pattern of associations observed across measurement approaches. This methodological transparency enhances the credibility of the empirical findings while contextualizing the results within the acknowledged measurement constraints inherent to environmental behavior research.

3.2. The Data Collection and Demographic Characteristics

This investigation employed a systematic quantitative research design to examine environmentally responsible behaviors among tourists in the heritage villages of Paveh County, Iran. The research context encompassed three historically significant settlements—Hajij, Nasmeh, and Khaneghah—strategically selected for their distinctive cultural landscapes, architectural heritage significance, and emerging tourism development trajectories. These villages represent archetypal examples of Iranian rural heritage destinations, characterized by traditional architectural forms, intact cultural practices, and growing tourism pressures that create potential tensions between conservation and development objectives. The data collection procedures involved structured questionnaires administered during a carefully defined five-month period (July–November 2024), corresponding with the peak tourism visitation to ensure representative sampling of tourist behaviors and experiences. The data collection timeframe enabled both weekend and weekday visitors to be systemically captured, ensuring the representation of diverse visitor segments, including short-stay excursionists and longer-duration heritage tourists.

The questionnaire administration implemented a systematic intercept methodology wherein trained research assistants approached potential respondents at key nodes within each village (central squares, primary heritage attractions, and accommodation facilities), employing a systematic sampling interval to minimize selection bias. Upon establishing initial eligibility through screening questions regarding their age (≥18 years) and visitation purpose (tourism-related activities), the research assistants delivered a thorough briefing on the study’s academic objectives and ensured the respondents were informed about their rights to anonymity and data confidentiality. Potential participants were guaranteed that their responses would be used solely for academic purposes and would remain completely anonymous, with no personally identifiable information gathered. The questionnaire completion process typically required 15–20 min, with the research assistants maintaining an appropriate distance to ensure response privacy while remaining available to clarify potential ambiguities. This methodological approach achieved a response rate of 78.3%, with 443 valid questionnaires collected from approximately 566 approached visitors. Non-responses were primarily attributable to time constraints rather than content objections, thus minimizing potential non-response bias concerns. The gender distribution (53.1% male, 46.9% female) and balanced age representation across demographic segments demonstrate the effectiveness of this systematic approach in capturing diverse visitor characteristics.

The sampling framework employed systematic convenience sampling, strategically implemented to capture diverse visitor segments while maintaining methodological rigor through careful consideration of demographic representation. The sample size was determined through an a priori power analysis using G*Power software (version 3.1), with the parameters set to detect medium effect sizes (f2 = 0.15) at α = 0.05 and power (1 − β) = 0.95, indicating a minimum required sample of 120 respondents to achieve adequate statistical power in structural equation modeling analyses. The final sample of 443 valid responses substantially exceeded this threshold, enhancing the analytical robustness and validity of the statistical conclusions. The data collection approach incorporated several methodological controls to enhance the representativeness, including (1) a balanced distribution across morning, afternoon, and evening timeframes to capture temporal variations in the visitor profiles; (2) proportional sampling across the three villages based on the estimated visitor volumes; (3) systematic monitoring of demographic characteristics during the data collection to ensure appropriate representation across age cohorts (16.1% aged 18–25, 31.5% aged 26–35, 26.6% aged 36–45, 17.5% aged 46–55, and 8.3% over 55), gender categories, and educational segments (9.8% with a diploma or a lower level of education, 44.8% with a bachelor’s degree, 30.1% with a master’s degree, and 15.3% with a doctoral degree); and (4) the implementation of data quality controls, including a response pattern analysis and a missing value assessment, to identify potentially problematic responses. These methodological controls collectively enhanced the sample quality while maintaining alignment with the established sampling framework.

The demographic composition of the respondents reveals distinctive patterns salient to heritage tourism research contexts (

Table 2). The sample exhibits a balanced gender representation with a slight male predominance, while the age stratification demonstrates concentration in economically active cohorts, particularly within the 26–45 age brackets (58.1%). This demographic profile aligns with the established patterns in cultural heritage visitation, wherein middle-aged constituencies demonstrate heightened engagement with historical landscapes and cultural narratives. Particularly noteworthy is the educational composition, with 90.2% of the respondents possessing tertiary qualifications—a characteristic frequently associated with heightened cultural capital and corresponding interest in heritage consumption experiences. This educational profile suggests potentially elevated environmental awareness and cultural sensitivity among the sample population, presenting advantageous conditions for examining place-based psychological constructs.

The analysis of the visitation parameters reveals substantive implications for place attachment theorization. The predominance of repeat visitors (78.3%) provides methodologically advantageous conditions for examining how iterative place experiences influence identity formation processes and subsequent conservation behaviors. The geographic distribution pattern—characterized by strong regional visitation (46.9%)—facilitates examination of proximity effects on place-based psychological connections, a theoretical dimension inadequately addressed in the extant literature on place attachment. The visit motivation analysis reveals a complementary heritage–nature orientation (72.1% combined), suggesting potential synergistic effects between cultural appreciation and environmental sensitivity. The extended duration of visitation (62.9% multiple-day stays) presents the optimal conditions for examining how the temporal dimensions of place experiences influence attachment formation and identity internalization processes. These demographic characteristics collectively constitute methodologically advantageous conditions for examining the theoretical propositions regarding the place–behavior relationships established in the conceptual framework while enabling a nuanced analysis of potential demographic moderators in environmental behavior formation within heritage tourism contexts.

3.3. The Measurement Models

In alignment with the research objectives, an assessment of the measurement model was conducted through a comprehensive two-stage evaluation process incorporating established reliability and validity criteria for reflective constructs, following

Hair et al.’s (

2019) recommendations for PLS-SEM analysis. The systematic assessment framework ensures methodological rigor while providing robust evidence for the psychometric properties of the theoretical constructs employed in this investigation.

The initial evaluation stage involved systematic examination of the factor loadings, internal consistency reliability, and convergent validity indicators. All measurement items demonstrated factor loadings substantially above the recommended 0.70 threshold, with values ranging from 0.723 to 0.892, indicating strong item–construct relationships and adequate indicator reliability. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeded the conventional 0.70 benchmark across all constructs, ranging from 0.705 to 0.793, while the composite reliability values demonstrated a superior performance, with a range of 0.704 to 0.812, confirming robust internal consistency reliability for all theoretical constructs. Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values surpassed the critical 0.50 threshold for all constructs, with values spanning 0.523 to 0.602, thereby confirming adequate convergent validity and establishing that each construct explains more than half of the variance in its respective indicators (

Table 3).

The model’s validity was tested using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which is detailed in

Table 4. This methodological approach compares the square root of the AVE values (displayed on the matrix diagonal) with inter-construct correlations. The analysis reveals that for all constructs, the square root of the AVE exceeds the corresponding inter-construct correlations, providing robust evidence of discriminant validity.

Specifically, the square root of the AVE values for the constructs are place identity (0.984), place attachment (0.886), norms (0.81), perceived behavioral control (0.845), attitudes (0.701), behaviors (0.853), and behavioral intention (0.249). In each instance, these values exceed the corresponding inter-construct correlations. For example, place identity’s correlations with the other constructs range from 0.204 to 0.617, all notably lower than its square root of the AVE (0.984). This pattern is consistent across all constructs, demonstrating stronger within-construct associations compared to the between-construct relationships.

To address the potential common method bias concerns inherent in self-reported behavioral measures, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted through an exploratory factor analysis. The unrotated factor solution revealed that the largest factor accounted for 34.7% of the total variance, substantially below the critical 50% threshold, indicating that common method bias did not pose a significant threat to the validity of findings. Additionally, examination of the correlation matrix revealed no correlations exceeding 0.90, further supporting the absence of severe multicollinearity issues.

The contemporary discriminant validity assessment was strengthened through an HTMT analysis, with all of the values falling below the stringent 0.85 criterion. The HTMT values ranged from 0.156 (place identity–behavioral intention) to 0.798 (environmental norms–perceived behavioral control), providing robust confirmation of the constructs’ distinctiveness according to the current methodological standards (

Table 5).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

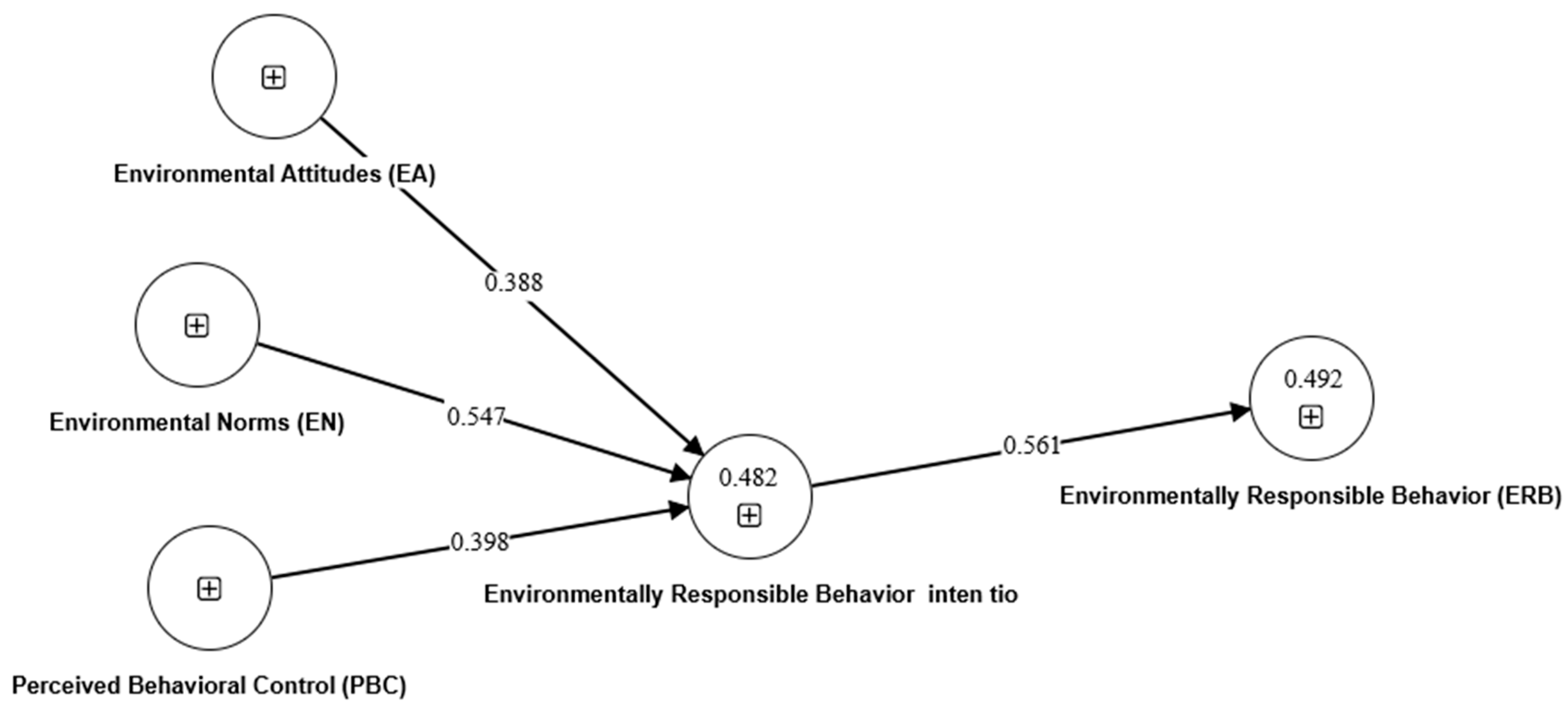

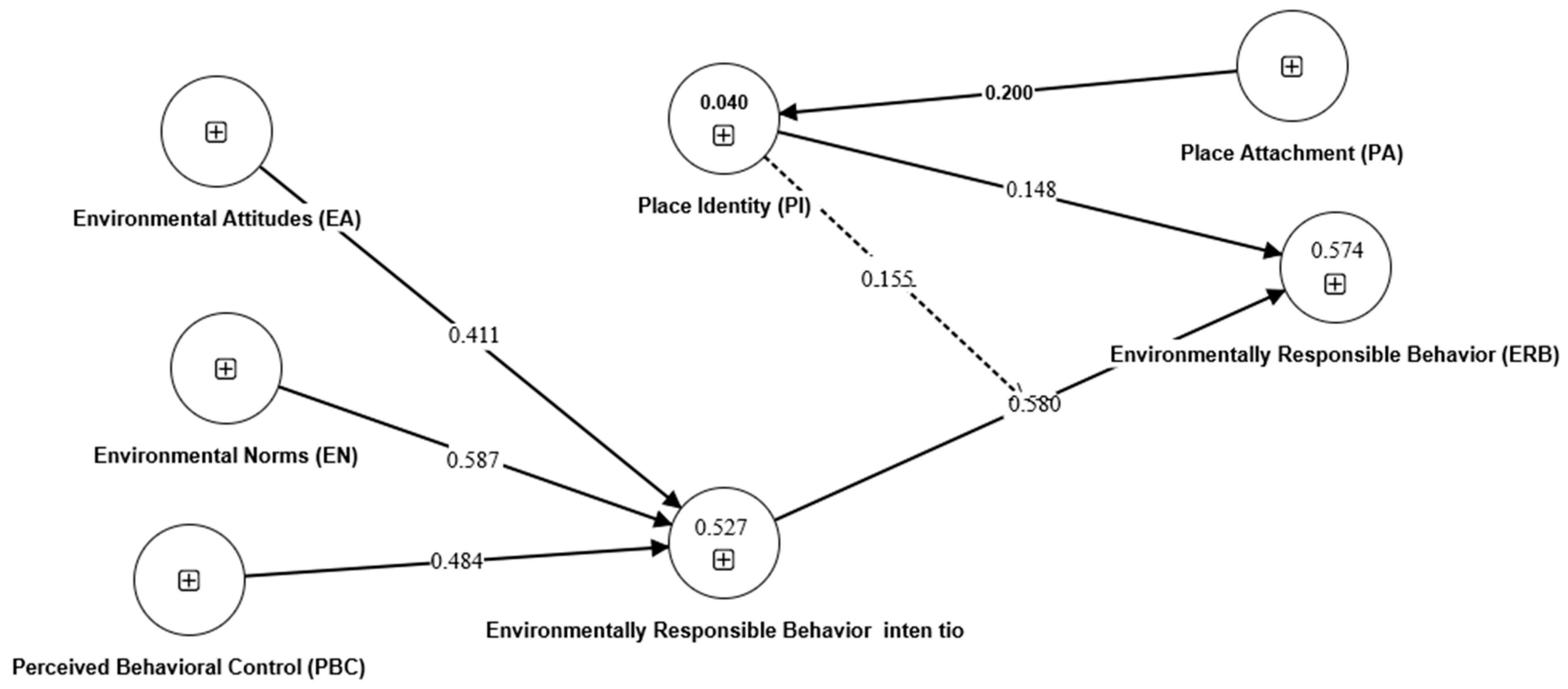

The present investigation provides significant empirical insights into the complex psycho-spatial determinants of environmentally responsible behavior among tourists visiting heritage villages in Paveh County, Iran, thereby extending the theoretical understanding beyond conventional applications of the TPB in tourism contexts. Through a rigorous structural equation modeling analysis (n = 443), this research systematically integrates place-related psychological constructs with the TPB, proposing a more robust theoretical framework that addresses critical gaps identified in the literature on environmental behavior within heritage tourism settings. The theoretical advancement achieved through this integration directly responds to calls for more sophisticated models that capture the distinctive characteristics of heritage destinations, where environmental behaviors acquire heightened significance due to their implications for both ecological sustainability and cultural preservation. Our findings demonstrate that environmental attitudes function as a fundamental antecedent of tourists’ behavioral intentions (β = 0.388,

p = 0.002 in the base model; β = 0.411,

p = 0.002 in the extended model), confirming the cognitive–evaluative pathway through which environmental concern manifests in behavioral predispositions while simultaneously revealing an enhanced predictive capacity when place-related variables are incorporated (

J. Cao et al., 2023). This empirically robust relationship aligns with established findings in heritage tourism contexts (

S. Wang et al., 2023), while the observed magnitude of the coefficient demonstrates remarkable consistency with recent investigations documenting the attitude–intention pathways in comparable cultural destinations (

Torabi et al., 2024). Of particular theoretical significance, the enhanced attitudinal effects following the integration of the place-related variables (Δβ = 0.023) coupled with the superior explanatory power of the extended model (R

2 increase from 0.482 to 0.527 for behavioral intentions) provide compelling evidence for interaction effects between cognitive evaluations and spatial–psychological connections—a mechanism inadequately addressed in previous theoretical frameworks, yet critical for understanding conservation behaviors in heritage contexts. These findings not only validate the theoretical proposition that place-based psychological connections systematically influence the traditional TPB components but also establish empirical support for developing more nuanced intervention strategies that simultaneously target environmental attitude formation and place identity strengthening through educational initiatives emphasizing local cultural–ecological interdependencies, interpretive programming highlighting heritage values, and community-based tourism experiences that foster meaningful visitor–place connections.

Integrating place-related constructs within the TPB framework yielded significant theoretical advancements in the contextual understanding of environmental conservation behaviors in heritage tourism settings. The empirical validation of place identity’s moderating effect on the intention–behavior relationship (β = 0.155,

p = 0.001) represents a critical contribution, illuminating the psychological mechanisms through which spatial connections enhance behavioral consistency (

Rao et al., 2022). This finding demonstrates notable alignment with

J. Cao et al.’s (

2023) documentation of place identity’s moderating influence in heritage contexts, while extending

Anton and Lawrence’s (

2016) conceptualization of identity–behavior linkages through more sophisticated methodological approaches. Particularly significant is the empirical demonstration that tourists with a stronger place identity exhibit enhanced translation of environmental intentions into observable conservation behaviors—a phenomenon that may partially explain the well-documented intention–behavior gap in environmental research. Furthermore, the identification of place identity’s mediating function between attachment and behavior (β = 0.163,

p < 0.001) provides empirical validation of

Chow et al. (

2019)’s theoretical propositions regarding attachment–behavior pathways, while offering enhanced analytical precision through the identification of specific psychological mechanisms. This mediational pathway establishes a coherent theoretical framework explaining how emotional connections to heritage sites (attachment) manifest in conservation behaviors through identity internalization processes, offering valuable insights for designing place-based interventions in environmentally sensitive heritage contexts.

The comparative analysis of the predictor variables revealed distinctive patterns of influence, with perceived behavioral control emerging as the dominant determinant of behavioral intentions in both the base model (β = 0.547,

p = 0.004) and the extended model (β = 0.578,

p < 0.001), substantially surpassing both attitudinal and normative influences. This finding demonstrates remarkable consistency with

Rao et al.’s (

2022) identification of efficacy perceptions as crucial behavioral antecedents, while the observed coefficient magnitudes align closely with

Torabi et al.’s (

2024) documentation of the control–intention pathways in comparable heritage settings. The substantial influence of environmental norms on behavioral intentions (β = 0.398,

p = 0.002; β = 0.484,

p = 0.006 in the extended model) corroborates

Sarmento and Loureiro’s (

2021) analysis of normative mechanisms in sustainable tourism contexts, particularly regarding the dual influence of descriptive and injunctive norms. Significantly, the enhanced normative effect following the integration of place-related variables (Δβ = 0.086) suggests potential interaction effects between social influence processes and spatial–psychological connections—a theoretical relationship inadequately addressed in previous frameworks. The robust intention–behavior relationship (β = 0.561,

p < 0.001; β = 0.580,

p < 0.001 in the extended model) validates the TPB’s fundamental proposition within heritage tourism contexts, while the significant enhancement in the variance explained for behavioral intentions (ΔR

2 = 0.045) and actual behavior (ΔR

2 = 0.055) following the integration of the place variables provides compelling empirical justification for the theoretical value of incorporating spatial–psychological dimensions in environmental behavior models.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The integration of place-related psychological constructs with established behavioral theories represents a significant theoretical advancement in understanding environmental conservation within heritage tourism contexts. This synthesis transcends the conventional socio-cognitive frameworks by acknowledging the distinctive spatial–psychological dimensions that characterize heritage experiences. Where the traditional behavioral models conceptualize environmental actions primarily through attitudinal–normative paradigms, our theoretical framework recognizes the complex interplay between cognitive evaluations and place-based psychological connections. The substantial enhancement in the model’s validity following place variable integration necessitates fundamental reconsideration of how environmental behaviors develop within culturally significant landscapes. This reconceptualization positions place not merely as context but as an active psychological agent in behavioral formation, suggesting that theoretical frameworks must account for the transformative influence of spatial–psychological connections on established behavioral mechanisms (

J. Cao et al., 2023). Moreover, this integrated approach enables more sophisticated modeling of the cognitive–spatial interface in heritage contexts, advancing the theoretical discourse beyond isolated examination of either psychological or spatial factors toward a more holistic understanding that acknowledges their systematic interdependence in conservation behavior formation.

The theoretical framework developed in this investigation establishes place identity as a multifunctional psychological construct operating through distinct yet complementary mechanisms in environmental behavior formation. The moderating function of place identity in the intention–behavior relationship illuminates how self-place connections influence motivational dynamics, potentially transforming abstract environmental intentions into personally meaningful behavioral commitments (

Wan et al., 2022). This moderation mechanism suggests that identity-based processes may fundamentally alter the psychological significance of environmental behaviors, reconfiguring them from generalized conservation actions to expressions of place-based identity. Concurrently, the mediational role of place identity between attachment and behavior reveals the transformative process through which emotional connections to heritage sites acquire behavioral significance. This dual-function conceptualization advances our theoretical understanding beyond linear models of environmental behavior, suggesting instead that place identity operates as both a catalyst and a conduit in conservation behavior formation. The theoretical significance of this conceptualization extends beyond heritage tourism contexts, potentially informing broader theoretical discourse regarding the psychological mechanisms connecting spatial attachment, identity formation, and behavioral expression across diverse environmental settings.

The theoretical model developed in this investigation contributes to the scholarly discourse by establishing a more sophisticated conceptual architecture for understanding the spatial–psychological dimensions of environmental behavior. This framework extends beyond tourism-specific theoretical traditions to engage with fundamental questions in environmental psychology regarding the interconnection between place experiences and behavioral outcomes. The incorporation of both direct and indirect pathways through which place influences behavior addresses previous theoretical limitations that have typically examined these relationships in isolation. Furthermore, this integrated framework enables systematic examination of the potential boundary conditions in place–behavior relationships, acknowledging that spatial influences may operate differently across behavioral domains, geographical scales, and cultural contexts. This contextual sensitivity represents an important theoretical advancement, suggesting the need for more nuanced conceptual models that account for potential variations in how place-related constructs influence different categories of environmental behaviors. By explicitly positioning place-related psychological processes within established behavioral frameworks while acknowledging contextual contingencies, this theoretical approach provides a foundation for more sophisticated cross-disciplinary dialogue between tourism studies, environmental psychology, and conservation behavior research.

5.2. Practical Implications

The empirical findings of this investigation yield significant managerial implications for heritage tourism stakeholders seeking to foster environmentally responsible behaviors within culturally significant destinations. The integrated theoretical framework provides evidence-based guidance for developing multidimensional management strategies that leverage both psychological and spatial determinants of conservation behaviors. Heritage tourism administrators, destination management organizations, and cultural preservation authorities would benefit from implementing a comprehensive approach addressing three critical domains: place-based interpretive strategies, infrastructural development, and stakeholder integration mechanisms. These strategic interventions respond directly to the demonstrated importance of place-related psychological connections in environmental behavior formation, providing destination managers with actionable pathways for enhancing sustainable tourism outcomes while preserving cultural integrity. The significant findings regarding the mediating role of place identity in the attachment–behavior relationship and its moderating effect on intention–behavior translation establish clear priorities for resource allocation and strategic planning in heritage tourism contexts.

Heritage site managers should prioritize interpretive strategies that systematically strengthen visitors’ psychological connections to these culturally significant locations, as demonstrated by the substantial influence of place identity on environmental behavior pathways. This theoretical insight translates into practical implementation through the development of multisensory interpretive programs emphasizing site-specific cultural narratives and historical authenticity; the implementation of interactive exhibitions that facilitate visitor engagement with tangible and intangible heritage elements; the creation of community-based tourism initiatives facilitating meaningful interactions between visitors and local residents; and the design of digital interpretation platforms that extend place-based connections beyond physical visitation. These interventions should be strategically designed to transform ephemeral tourism experiences into enduring psychological connections capable of sustaining long-term environmental stewardship commitments. Destination managers should simultaneously develop place-focused marketing strategies that emphasize the distinctive cultural characteristics of heritage villages, thereby cultivating pre-visit place connections that can be subsequently strengthened through on-site experiences and interpretive programs. The integration of storytelling techniques, participatory cultural activities, and immersive heritage experiences will enhance the emotional resonance of visitor encounters while fostering deeper appreciation for local environmental conservation needs.

The differential impacts of environmental attitudes and perceived behavioral control on behavioral intentions necessitate a multifaceted approach to environmental management combining educational initiatives with infrastructural development. Heritage site administrators should implement a comprehensive intervention strategy addressing attitudinal, normative, and control dimensions simultaneously through the development of environmental education programs highlighting the ecological–cultural interdependencies within heritage settings, the establishment of visible infrastructural support systems, including strategically positioned waste management facilities and clear designation of environmentally sensitive zones, and the creation of enabling conditions for sustainable practices through eco-friendly transportation options and sustainable consumption alternatives. The enhanced explanatory power of the extended theoretical model provides empirical justification for allocating resources to place-strengthening initiatives, including the development of interpretation centers highlighting environmental–cultural connections, the creation of heritage trails integrating natural and cultural elements, and the implementation of community-based conservation programs that engage visitors in meaningful place-based activities. These strategic interventions should be supported by systematic monitoring and evaluation frameworks employing both behavioral and psychological metrics to assess program effectiveness, facilitate continuous improvements in sustainable tourism management practices, and ensure the long-term sustainability of heritage villages as authentic cultural destinations that successfully balance conservation objectives with tourism development needs.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Even with the theoretical progress and empirical insights generated, this investigation exhibits several methodological and conceptual limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, the cross-sectional research design precludes definitive causal inferences regarding the temporal sequence through which place attachment and identity influence environmental behaviors, limiting our ability to establish temporal precedence despite the theoretical plausibility of the proposed relationships. Second, the geographically constrained sample drawn exclusively from Paveh County’s heritage villages raises questions regarding the generalizability to other heritage contexts with distinctive cultural characteristics, architectural forms, and tourism development trajectories. Third, the reliance on self-reported behavioral measures introduces potential social desirability bias, particularly given the normative expectations surrounding environmental conservation in heritage settings, which may inflate the behavioral engagement reported. Fourth, the relatively modest sample size (n = 443), while methodologically justified through the power analysis, potentially constrains the detection of smaller effect sizes and limits the feasibility of multi-group analyses that might reveal important demographic or experiential moderators. Finally, the measurement approach utilizing adapted Western-developed scales, despite rigorous cultural contextualization efforts, may not fully capture the culturally specific dimensions of place attachment and identity formation processes that characterize Iranian heritage experiences.

Building upon these identified limitations, several promising research trajectories emerge that could substantially advance the theoretical understanding of place–behavior relationships in heritage tourism contexts. Future investigations should prioritize methodological diversification through longitudinal research designs capable of capturing the dynamic evolution of place attachments and subsequent behavioral manifestations across multiple heritage experiences, thereby establishing clearer temporal sequencing. The development of more culturally sensitive measurement instruments through collaborative cross-cultural scale development initiatives would enhance the construct validity, particularly regarding place-related psychological dimensions, which may manifest differently across cultural contexts. Researchers should explore complementary theoretical integrations, particularly incorporating Value–Belief–Norm Theory or the Model of Goal-Directed Behavior alongside the TPB and place constructs, potentially enhancing the explanatory power through more comprehensive motivational frameworks. Of significant practical value would be experimental intervention studies systematically examining the efficacy of interpretive strategies, immersive experiences, and narrative techniques in strengthening place identity formation and subsequent environmental behaviors, employing sophisticated methodological designs to establish causal relationships. Additionally, future research should expand the theoretical dimensionality by incorporating variables reflecting technological mediation of place experiences, climate change risk perceptions, and intergenerational equity considerations, while simultaneously exploring boundary conditions through visitor segmentation based on their motivational orientations, cultural backgrounds, and environmental experience profiles.