Enhancing Health Tourism Through Gamified Experiences: A Structural Equation Model of Flow, Value, and Behavioral Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Gamification in Tourism

2.1.2. Flow Theory

2.1.3. Perceived Value

2.1.4. Behavioral Intention

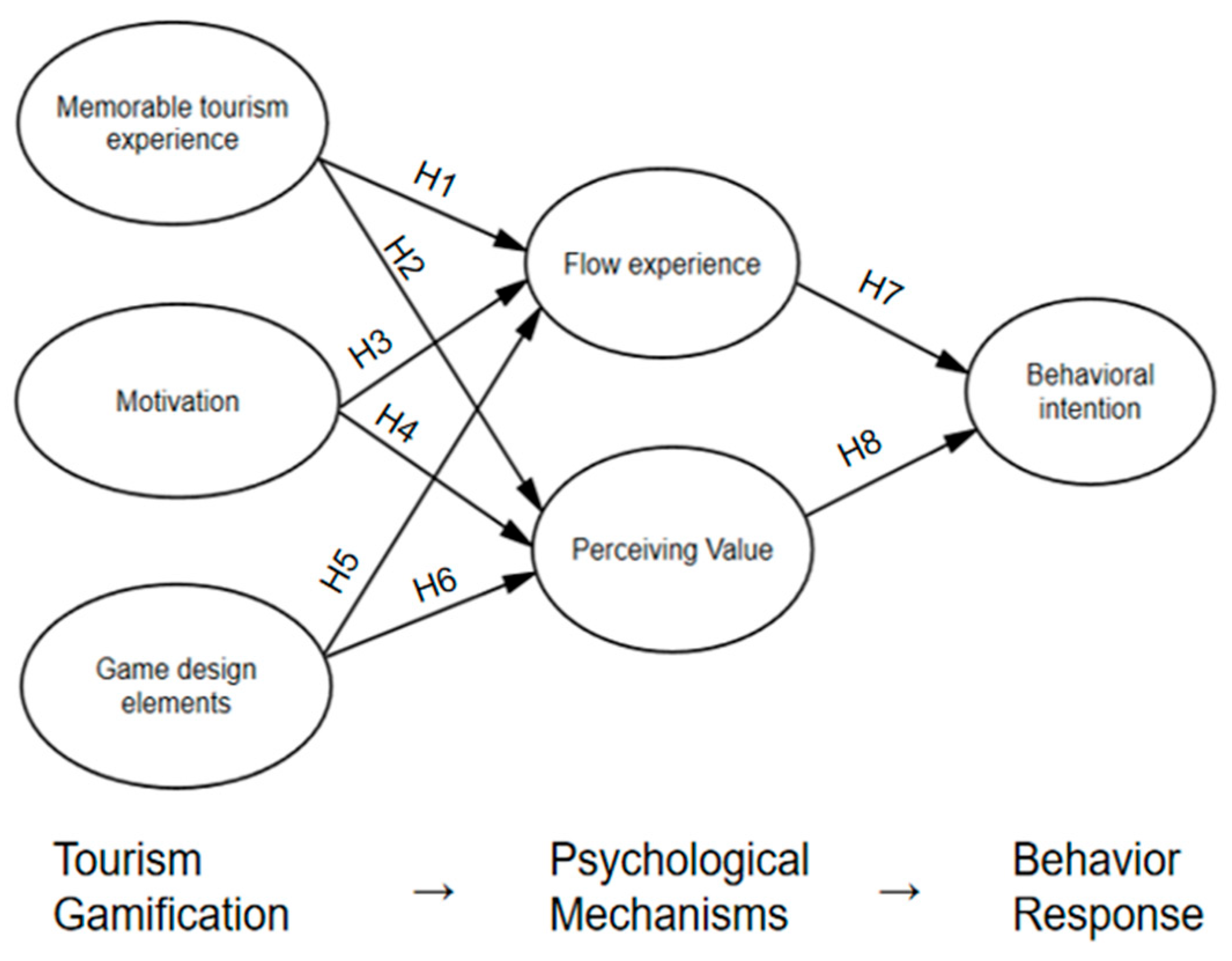

2.2. Development of Research Hypotheses

3. Research Method

3.1. Sampling Design and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Development

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.1.1. Reliability Analysis

4.1.2. Convergent Validity

4.1.3. Discriminant Validity

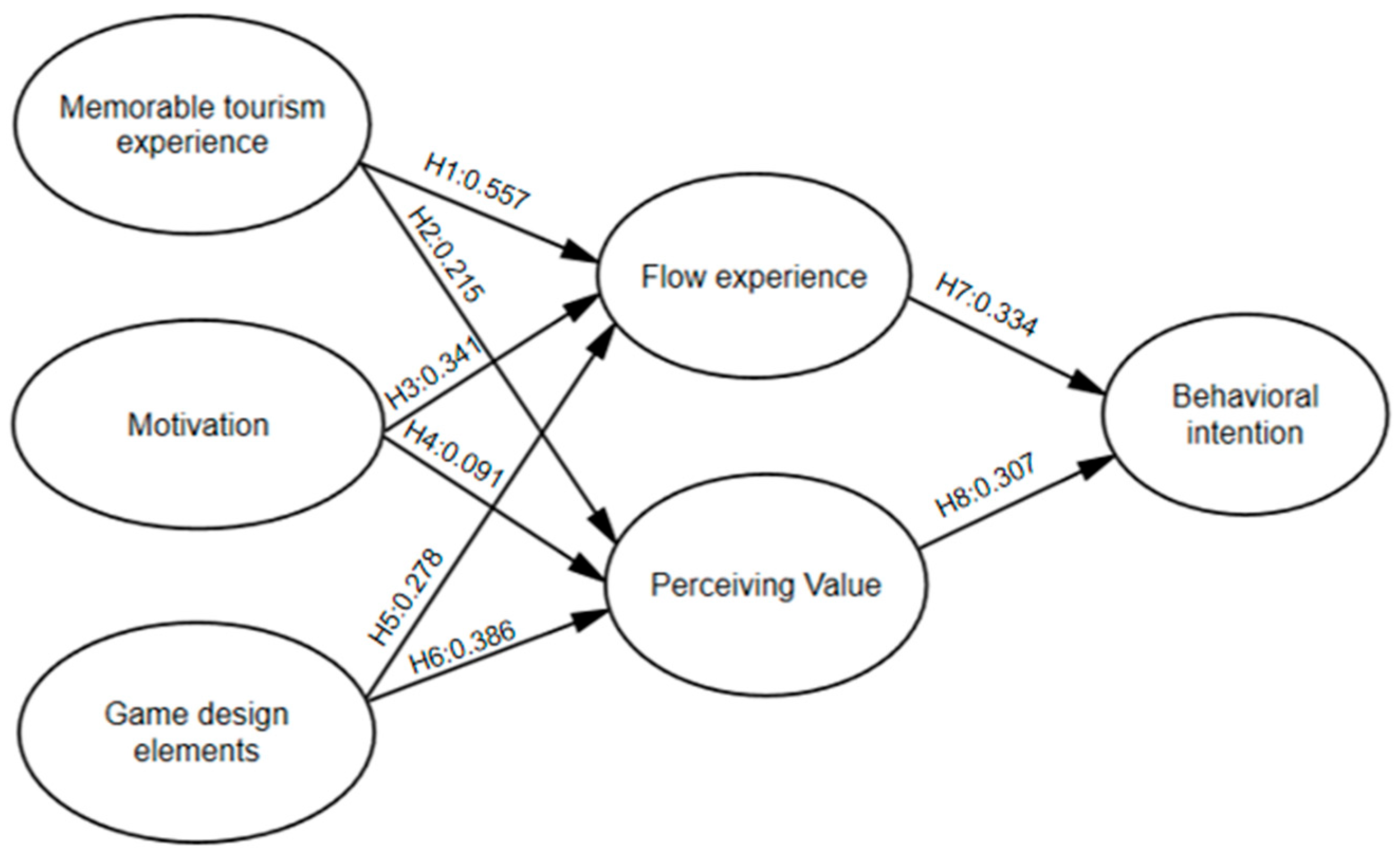

4.2. Structural Model Analysis

4.3. The SEM Effects of the Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Significance

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MTE | Memorable tourism experience |

| MOT | Motivation |

| GDE | Game design elements |

| FLE | Flow experience |

| PEV | Perceiving value |

| BEI | Behavioral intention |

References

- Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Castillo, L., Hernández-López, L., De Saá-Pérez, P., & Perez-Jimenez, R. (2020). Gamification as a motivation strategy for higher education students in tourism face-to-face learning. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 27, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N., Khan, N., Mahroof Khan, M., Ashraf, S., Hashmi, M. S., Khan, M. M., & Hishan, S. S. (2021). Post-COVID 19 tourism: Will digital tourism replace mass tourism? Sustainability, 13(10), 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A., Hiselius, L. W., & Adell, E. (2018). Promoting sustainable travel behaviour through the use of smartphone applications: A review and development of a conceptual model. Travel Behaviour and Society, 11, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C., Camarero, C., Laguna, M., & Buhalis, D. (2019). Impacts of authenticity, degree of adaptation and cultural contrast on travellers’ memorable gastronomy experiences. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(7), 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W. B., Wang, J. J., Wong, J. W. C., Han, X. H., & Guo, Y. (2024). The soundscape and tourism experience in rural destinations: An empirical investigation from Shawan Ancient Town. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J., Rainoldi, M., & Egger, R. (2019). Virtual reality in tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tourism Review, 74(3), 586–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A., Schlager, T., Sprott, D. E., & Herrmann, A. (2018). Gamified interactions: Whether, when, and how games facilitate self–brand connections. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46, 652–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, M. R. (2000). Towards an understanding of flow and other positive experience phenomena within outdoor and adventurous activities. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1(1), 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004, April). A grounded investigation of game immersion. In CHI’04 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1297–1300). ACM Digital Library. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, F., Trunfio, M., Pasquinelli, C., Sorrentino, A., Campana, S., & Rossi, S. (2022). Technology-driven innovation. Exploiting ICTs tools for digital engagement, smart experiences, and sustainability in tourism destinations. Enzo Albano Edizioni Naples. SLIOB. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. S., Chan, Y. H., & Fong, T. H. A. (2020). Game-based e-learning for urban tourism education through an online scenario game. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 29(4), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. F., & Chen, F. S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Cheng, Z. F., & Kim, G. B. (2020). Make it memorable: Tourism experience, fun, recommendation and revisit intentions of Chinese outbound tourists. Sustainability, 12(5), 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., Joo, D., Moore, D., & Norman, W. C. (2019). Sport tourists’ nostalgia and its effect on attitude and intentions: A multi level approach. Tourism Management Perspectives, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M., & Gosling, M. (2018). Memorable tourism experience (MTE): A scale proposaland test. Tourism & Management Studies, 14(4), 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, C., & Kitano, C. (2015, February). Gamification in tourism: Analysis of brazil quest game. In Proceedings of ENTER, Lugano, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286926048_Gamification_in_Tourism_Analysis_of_Brazil_Quest_Game (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., Jr., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Beyond boredom and anxiety. Jossey-Bass. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-12701-000 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- da Silva deMatos, N. M., de Sa, E. S., & de Oliveira Duarte, P. A. (2021). A review and extension of the flow experience concept. Insights and directions for Tourism research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011, September). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic mindtrek conference: Envisioning future media environments (pp. 9–15). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M., Laguna, M., & Palacios, A. (2010). The role of motivation in visitor satisfaction: Empirical evidence in rural tourism. Tourism Management, 31(4), 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H. M., & Hung, K. P. (2021). The antecedents of visitors’ flow experience and its influence on memory and behavioral intentions in the music festival context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R., & El-Gohary, H. (2015). The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction. Tourism Management, 46, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppmann, R., Bekk, M., & Klein, K. (2018). Gameful experience in gamification: Construction and validation of a gameful experience scale [GAMEX]. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 43(1), 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N. H. (1993). Moods, emotion episodes, and emotions. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-98937-021 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Ghaderi, Z., Rajabi, M., Butler, R., & Beal, L. (2024). Flow experience and behavioural intention in recreational flights: The mediating role of satisfaction, recollection and storytelling. Anatolia, 36, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M., Baker, C., & Fyall, A. (2022). VR in tourism: A new call for virtual tourism experience amid and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, C. (2000). Tourism information and pleasure motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J. P. (2021). Do game transfer phenomena lead to flow? An investigation of in-game and out-game immersion among MOBA gamers. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. (2017). Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on the effects of gamification. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.-H., & Lee, G.-H. (2022). Analysis of consensus map of Memorable Tourism Experience (MTE): An application of Zaltman’s Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET) method. Journal of Tourism Sciences, 46(8), 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M. E., & Dimanche, F. (1999). Leisure involvement revisited: Drive properties and paradoxes. Journal of Leisure Research, 31(2), 122–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. L., & Chen, M. C. (2018). How gamification marketing activities motivate desirable consumer behaviors: Focusing on the role of brand love. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Lang, C., Corbet, S., & Wang, J. (2024). The impact of COVID-19 on the volatility connectedness of the Chinese tourism sector. Research in International Business and Finance, 68, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Shen, Y., & Choi, C. (2015). The effects of motivation, satisfaction and perceived value on tourist recommendation. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/32439902.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Huang, Y. F., Zhang, Y., & Quan, H. (2019). The relationship among food perceived value, memorable tourism experiences and behaviour intention: The case of the Macao food festival. International Journal of Tourism Sciences, 19(4), 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2012, October). Defining gamification: A service marketing perspective. In Proceeding of the 16th international academic MindTrek conference (pp. 17–22). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A., & Sharifuddin, J. (2015). Perceived value and perceived usefulness of halal labeling: The role of religion and culture. Journal of Business Research, 68(5), 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kanagasapapathy, G. (2017). Understanding the flow experiences of heritage tourists [Ph.D. dissertation, Bournemouth University]. Available online: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/29882/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Kim, J. H. (2018). The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Thapa, B. (2018). Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. Journal of destination Marketing & Management, 8, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. J., & Hall, C. M. (2019). A hedonic motivation model in virtual reality tourism: Comparing visitors and non-visitors. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. N., Lee, Y., Suh, Y. K., & Kim, D. Y. (2021). The effects of gamification on tourist psychological outcomes: An application of letterboxing and external rewards to maze park. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(4), 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majuri, J., Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2018, April 9–10). Gamification of education and learning: A review of empirical literature. In Proceedings of the 2nd International GamiFIN Conference (Vol. 2186, pp. 11–19), Pori, Finland. Available online: https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/104598/gamification_of_education_2018.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Mannell, R. C., & Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1987). Psychological nature of leisure and tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 14(3), 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C., da Silva, R. V., & Antova, S. (2021). Image, satisfaction, destination and product post-visit behaviours: How do they relate in emerging destinations? Tourism Management, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, G. B., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. Journal of Personality, 64(2), 275–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, J. K., & Sabherwal, R. (2020). Gamification: A cognitive-emotional view. Journal of Business Research, 106, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of mihaly csikszentmihalyi (pp. 239–263). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negruşa, A. L., Toader, V., Sofică, A., Tutunea, M. F., & Rus, R. V. (2015). Exploring gamification techniques and applications for sustainable tourism. Sustainability, 7(8), 11160–11189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4684-2490-4_4 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Pandža Bajs, I. (2015). Tourist perceived value, relationship to satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The example of the Croatian tourist destination Dubrovnik. Journal of Travel Research, 54(1), 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, M. G., Renzi, M. F., Di Pietro, L., & Guglielmetti Mugion, R. (2021). Gamification in tourism and hospitality research in the era of digital platforms: A systematic literature review. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 31(5), 691–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J., Yang, X., Fu, S., & Huan, T. C. T. (2023). Exploring the influence of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention in the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine cultural tourism. Tourism Management, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D., Malik, G., & Vishwakarma, P. (2025). Gamification in tourism research: A systematic review, current insights, and future research avenues. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 31(1), 130–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2013). Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2011). Introduction to psychometric theory. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H., Sarpong, D., & White, G. R. (2018). Meeting the needs of the Millennials and Generation Z: Gamification in tourism through geocaching. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V. S., & Marques, S. R. B. D. V. (2022). Factors influencing urban tourists’ receptivity to ecogamified applications: A study on transports and mobility. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(4), 820–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swacha, J. (2019). Architecture of a dispersed gamification system for tourist attractions. Information, 10(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. (2021). COVID-19 and tourism in 2020: A year in review. UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- UNWTO. (2024). International tourism to reach pre-pandemic levels in 2024. UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-to-reach-pre-pandemic-levels-in-2024 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Wei, C., Zhao, W., Zhang, C., & Huang, K. (2019). Psychological factors affecting memorable tourism experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(7), 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Buhalis, D., & Weber, J. (2017). Serious games and the gamification of tourism. Tourism Management, 60, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., & Fox, D. (2014). Modelling attitudes to nature, tourism and sustainable development in national parks: A survey of visitors in China and the UK. Tourism Management, 45, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Tian, F., Buhalis, D., Weber, J., & Zhang, H. (2021). Tourists as mobile gamers: Gamification for tourism marketing. In Future of tourism marketing (pp. 96–114). Routledge. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003176039-9/tourists-mobile-gamers-gamification-tourism-marketing-feifei-xu-feng-tian-dimitrios-buhalis-jessica-weber-hongmei-zhang (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Xu, F., Weber, J., & Buhalis, D. (2014, January). Gamification in tourism. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014: Proceedings of the international conference in Dublin, Ireland, January 21–24, 2014 (pp. 525–537). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J., & Liu, B. (2023). Does distance produce beauty? The impact of cognitive distance on tourists’ behavior intentions: An intergenerational difference perspective. Tourism Tribune, 38, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(1), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wu, Y., & Buhalis, D. (2018). A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zichermann, G., & Linder, J. (2010). Game-based marketing: Inspire customer loyalty through rewards, challenges, and contests. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 215 | 53.9 |

| Female | 184 | 46.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 21–30 | 142 | 35.6 |

| 31–40 | 154 | 38.6 |

| >40 | 63 | 15.8 |

| Education | ||

| High school or below | 29 | 7.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 256 | 64.2 |

| Master’s degree or above | 114 | 28.5 |

| Frequency of visiting scenic areas that include game design elements | ||

| 1–2 times per year | 73 | 18.3 |

| 3 or more times per year | 326 | 81.7 |

| Construct | Item | Cronbach’s α | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memorable tourism experience | MTE1: I really enjoyed this travel experience. | 0.908 | J. H. Kim (2018). Cho et al. (2019). Wei et al. (2019). Antón et al. (2019). Zhang et al. (2018) |

| MTE2: I learned more about myself through this travel experience. | |||

| MTE3: I experienced new things during this travel experience. | |||

| Motivation | MOT1: My main purpose for traveling is to experience different cultures, places, and atmospheres, learn new things, and meet people who are different from me. | 0.788 | M. Kim and Thapa (2018). Kanagasapapathy (2017). S. Huang et al. (2015). |

| MOT2: My purpose for traveling is to temporarily forget about work and responsibilities, relax, and relieve stress. | |||

| MOT3: My main purpose for traveling is to improve relationships with others, spend time with family and friends, and meet like-minded people | |||

| Game design elements | GDE1: The reason I chose to experience this tourist attraction is because it showcases unique creativity through gamification elements (such as NPC interaction, game levels, and scene recreation), allowing me to experience a unique travel story in the real world. | 0.804 | Frijda (1993). Gutierrez (2021). Chan et al. (2020). Eppmann et al. (2018) |

| GDE2: I am confident that I can successfully complete the gamified tasks at this tourist attraction, such as interacting with NPCs, completing game levels, or exploring virtual scenes, and enjoy the fun of it. | |||

| GDE3: When I engage in gamified experiences at this tourist attraction, I feel like I have entered a world that feels more real than reality, almost as if I am in a virtual scene from an online game. | |||

| Flow experience | FLE1: Have you experienced flow during your travel? | 0.904 | Bai et al. (2024) M. J. Kim and Hall (2019) Marques et al. (2021) M. Kim and Thapa (2018). Kanagasapapathy (2017). |

| FLE2: Most of the time, do you feel like you are experiencing flow? | |||

| FLE3: I was completely immersed in this trip. | |||

| Perceiving value | PEV1: Gamified tourism makes me feel pleasant, relaxed, and I really enjoy the experience. | 0.866 | Peng et al. (2023) Pandža Bajs (2015) Cronin et al. (2000) M. Kim and Thapa (2018). J. H. Kim (2018). |

| PEV2: Gamified tourism not only improves my perception of travel, but also leaves a lasting impression on others, enhancing my social identity with them. | |||

| PEV3: Gamified tourism is consistently high quality in every aspect, especially in NPC interactions, game levels, and the recreation of virtual scenes. | |||

| Behavioral intention | BEI1: I will give a positive verbal evaluation of this travel experience. BEI2: I will recommend this destination to others. BEI3: I will revisit this place in the future. | 0.895 | J. H. Kim (2018). M. Kim and Thapa (2018). Marques et al. (2021). Cronin et al. (2000). |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Construct Reliability | Convergent Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | |||

| Memorable tourism experience | MTE1 | 0.938 | 0.920 | 0.793 |

| MTE2 | 0.866 | |||

| MTE3 | 0.865 | |||

| Motivation | MOT1 | 0.798 | 0.810 | 0.588 |

| MOT2 | 0.685 | |||

| MOT3 | 0.812 | |||

| Game design elements | GDE1 | 0.830 | 0.808 | 0.585 |

| GDE2 | 0.725 | |||

| GDE3 | 0.735 | |||

| Flow experience | FLE1 | 0.928 | 0.911 | 0.774 |

| FLE2 | 0.854 | |||

| FLE3 | 0.855 | |||

| Perceiving value | PEV1 | 0.944 | 0.874 | 0.700 |

| PEV2 | 0.756 | |||

| PEV3 | 0.799 | |||

| Behavioral intention | BEI1 | 0.945 | 0.902 | 0.756 |

| BEI2 | 0.818 | |||

| BEI3 | 0.840 |

| MTE | MOT | GDE | FLE | PEV | BEI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTE | 0.891 | |||||

| MOT | 0.153 | 0.767 | ||||

| GDE | 0.181 | 0.310 | 0.765 | |||

| FLE | 0.429 | 0.258 | 0.243 | 0.880 | ||

| PEV | 0.327 | 0.210 | 0.375 | 0.205 | 0.837 | |

| BEI | 0.204 | 0.125 | 0.150 | 0.377 | 0.248 | 0.869 |

| Path | Path Coefficient | p Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Memorable tourism experience has a positive effect on flow experience. | 0.557 | *** 1 | Yes |

| H2: Memorable tourism experience has a positive effect on perceived value. | 0.215 | *** 1 | Yes |

| H3: Motivation has a positive effect on flow experience. | 0.341 | 0.004 | Yes |

| H4: Motivation has a positive effect on perceived value. | 0.091 | 0.178 | NO |

| H5: Game design elements have a positive effect on flow experience. | 0.278 | 0.027 | Yes |

| H6: Game design elements have a positive effect on perceived value. | 0.386 | *** 1 | Yes |

| H7: Flow experience has a positive effect on behavioral intention. | 0.334 | *** 1 | Yes |

| H8: Perceived value has a positive effect on behavioral intention. | 0.307 | *** 1 | Yes |

| Path | Effect | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrapped Lower Limit | Bootstrapped Upper Limit | ||||

| Memorable tourism experience—flow experience—behavioral intention | Total effect | 0.668 | 0.538 | 0.814 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | 0.527 | 0.386 | 0.680 | 0.000 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.141 | 0.074 | 0.213 | 0.000 | |

| Memorable tourism experience—perceived value—behavioral intention | Total effect | 0.670 | 0.539 | 0.816 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | 0.072 | 0.026 | 0.136 | 0.000 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.072 | 0.026 | 0.136 | 0.003 | |

| Motivation—flow experience—behavioral intention | Total effect | 0.480 | 0.268 | 0.742 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | 0.299 | 0.092 | 0.539 | 0.002 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.181 | 0.100 | 0.296 | 0.000 | |

| Motivation—perceived value—behavioral intention | Total effect | 0.487 | 0.274 | 0.754 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | 0.382 | 0.168 | 0.638 | 0.001 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.105 | 0.034 | 0.225 | 0.002 | |

| Gamification design elements—flow experience—behavioral intention | Total effect | 0.228 | −0.008 | 0.482 | 0.061 |

| Direct effect | 0.032 | −0.196 | 0.276 | 0.775 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.196 | 0.096 | 0.345 | 0.000 | |

| Gamification design elements—perceived value—Behavioral intention | Total effect | 0.229 | −0.008 | 0.481 | 0.063 |

| Direct effect | −0.005 | −0.249 | 0.266 | 0.972 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.235 | 0.134 | 0.371 | 0.000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, T.; Chen, M. Enhancing Health Tourism Through Gamified Experiences: A Structural Equation Model of Flow, Value, and Behavioral Intentions. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030140

Qin T, Chen M. Enhancing Health Tourism Through Gamified Experiences: A Structural Equation Model of Flow, Value, and Behavioral Intentions. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030140

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Tianhao, and Maowei Chen. 2025. "Enhancing Health Tourism Through Gamified Experiences: A Structural Equation Model of Flow, Value, and Behavioral Intentions" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030140

APA StyleQin, T., & Chen, M. (2025). Enhancing Health Tourism Through Gamified Experiences: A Structural Equation Model of Flow, Value, and Behavioral Intentions. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030140