Tracking Tourism Waves: Insights from Automatic Identification System (AIS) Data on Maritime–Coastal Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

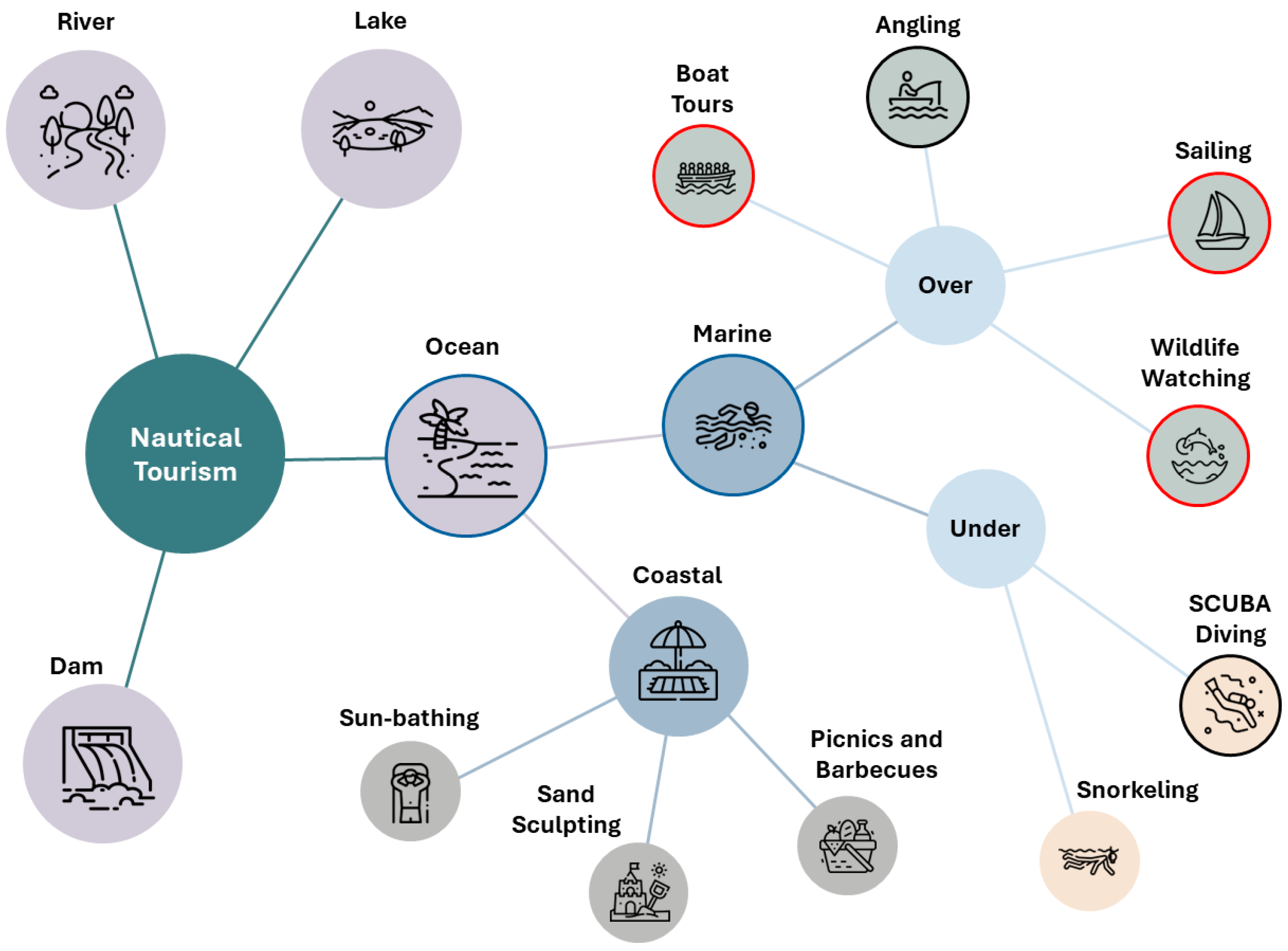

2.1. Nautical Activities

2.2. Nautical Tourist Profile

2.3. Economic and Environmental Impact of Nautical Activities Supported by Motorised Boats

2.4. Data Georeferencing in Activity Monitoring

2.5. Analysis of Georeferenced Data in Tourism Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Question

- What types of boating activities are related to the central area of the Algarve?

3.2. Experimental Design to Address Research Question

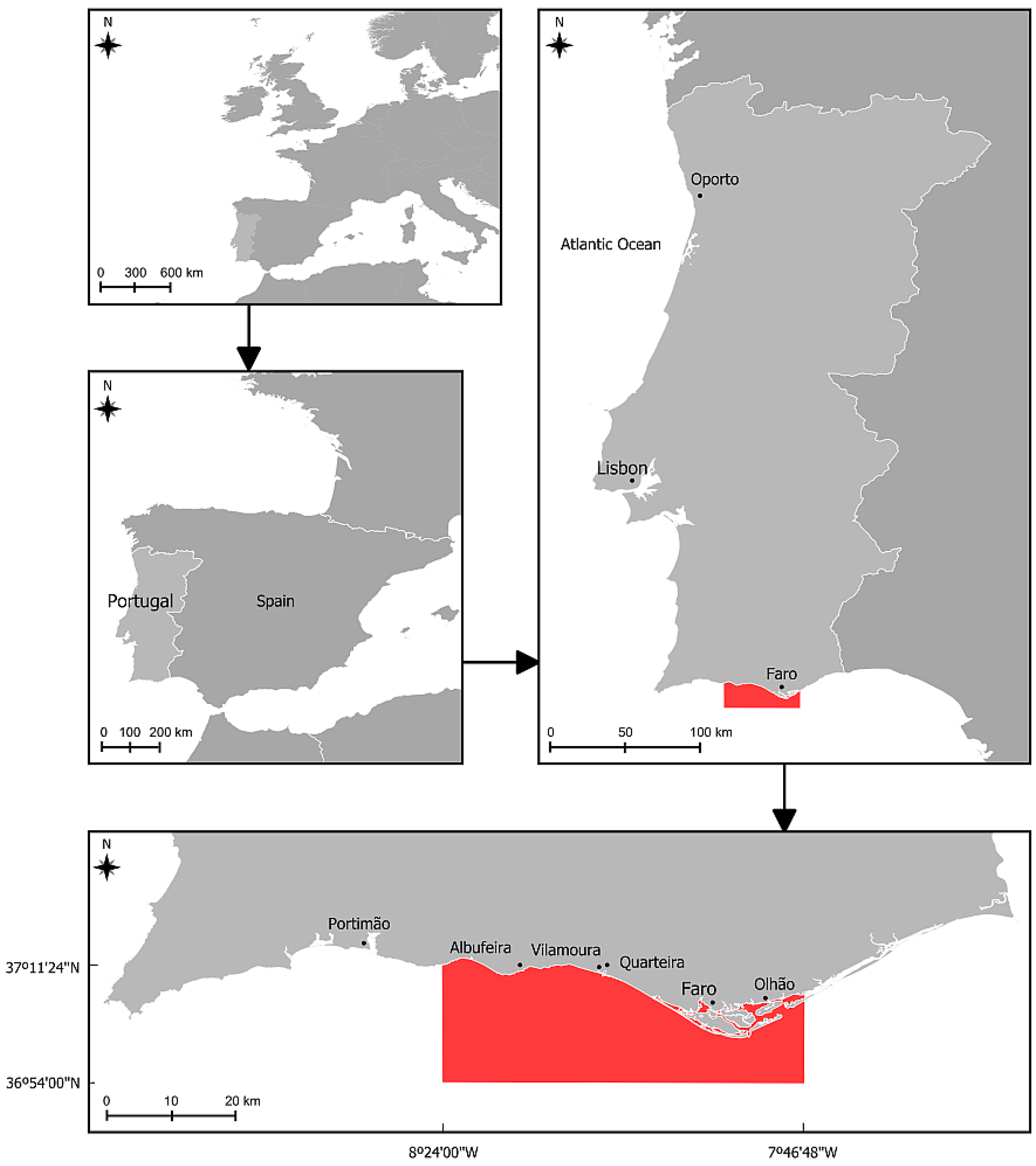

3.3. Case Study: Coastal and Maritime Central Algarve Area

3.4. AIS Data

3.5. MMSI of Vessels and AIS Records of Maritime-Tourist Activity

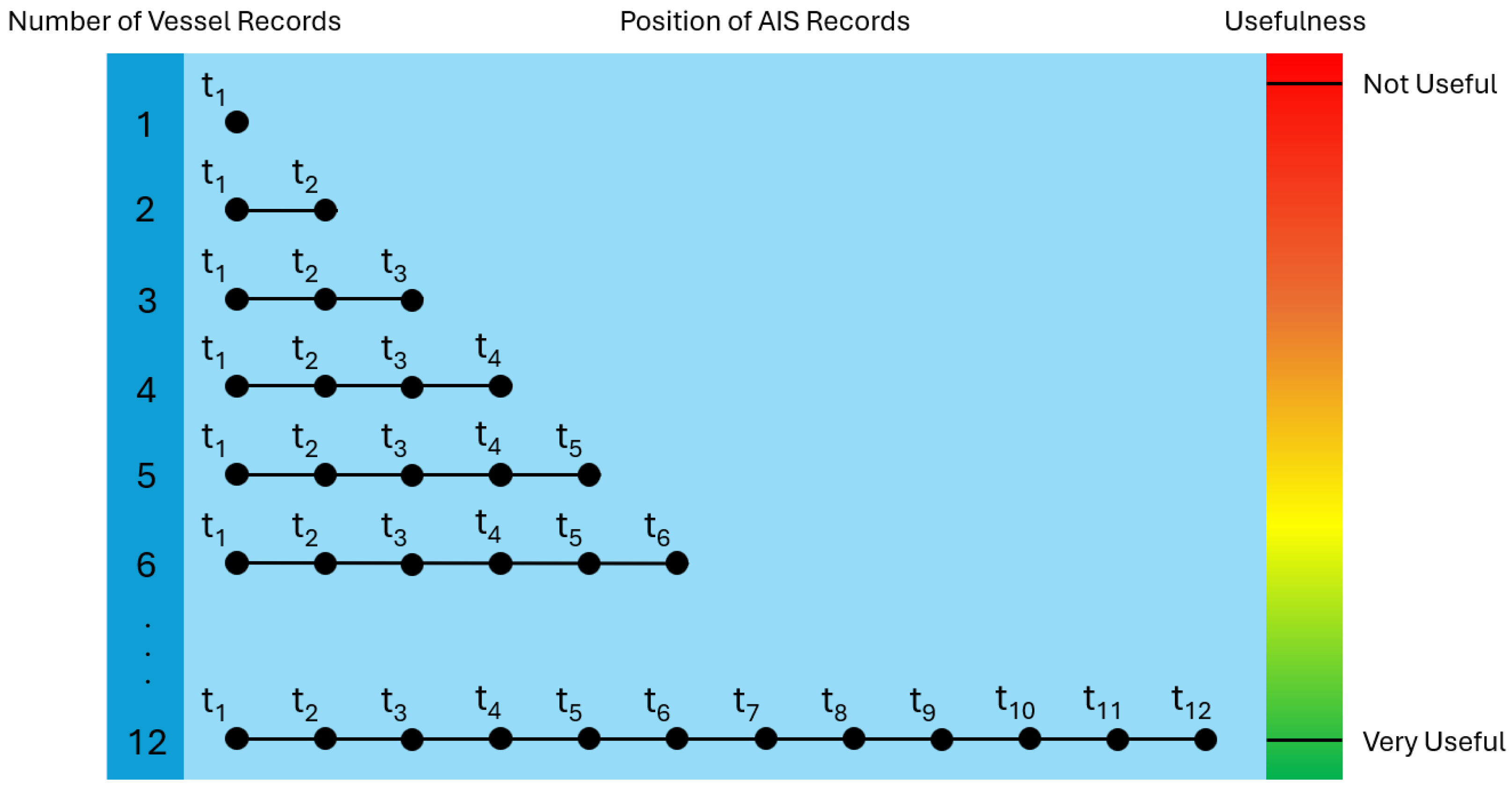

3.6. Finding a Feasible Number of Daily AIS Records

4. Results

4.1. Vessels Detected and Their Records of Maritime-Tourist Activity

4.2. Dispersion of AIS Data

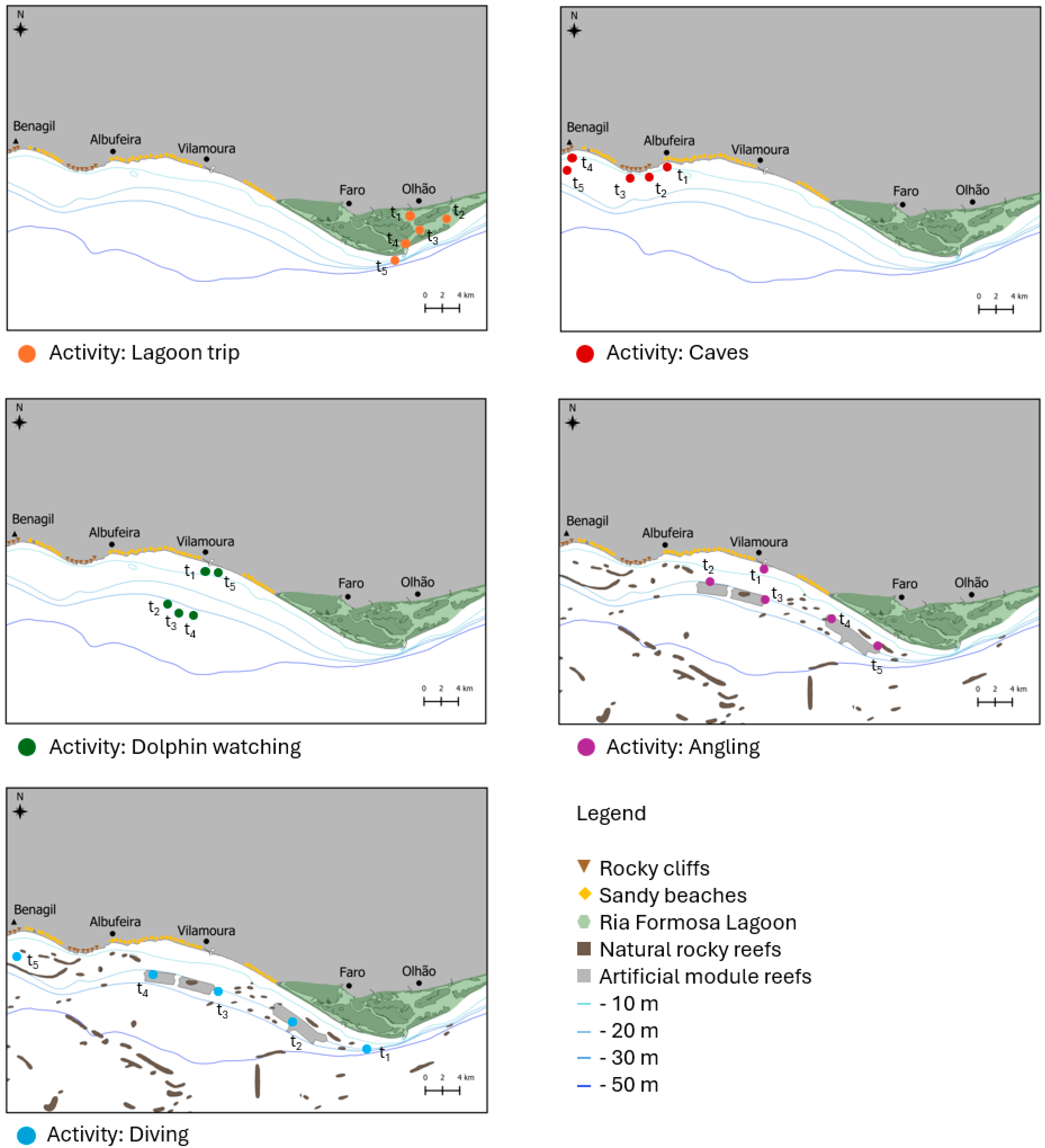

4.3. Allocation of Records by Type of Activity Detected

5. Discussion

5.1. Berthing Locations and Types of Vessels Offering Maritime Activities

5.2. Selection of Collected AIS Data Records and Analysis

5.3. Activity Patterns Depending on Geographic Area

5.4. Synthesis of Detected Patterns

6. Conclusions

- -

- Activities diversification—Encourage diversification of maritime–coastal tourist activities, providing incentives for firms that introduce new activities, to attract a wider range of tourists.

- -

- Seasonal regulation—Introduce seasonal regulations to manage peak season activity, such as capability limits of motorised nautical activities at sensitive sites (e.g., Benagil cave), ensuring more sustainable tourist practices and protection of coastal areas during periods of high demand.

- -

- Certification—Strengthen the application of certification needed for certain maritime activities to improve safety and ensure high-quality services, especially for activities involving motorised boats.

- -

- AIS data for monitoring—Use AIS data to support real-time monitoring of boat traffic, allowing for better supervision over tourism flow, thus enhancing security and decreasing environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | automatic identification system |

| CBT | cetacean-based tourism |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MMSI | Maritime Mobile Service Identity |

| QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System |

| SCUBA | self-contained underwater breathing apparatus |

| SOG | speed over ground (of the vessel) |

| TORMA | type of recreational maritime activity |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Model

- Y is the outcome variable of interest, derived from the combination of the vessel’s MMSI.

- β0 is the intercept term.

- β1, β2, β3, β4, and β5 are the coefficients for each predictor variable.

- ε is the error term, accounting for the variability in Y not explained by the model.

- Dc is the distance from the coast (continuous). It represents the distance of the vessel from the nearest coastline (in kilometres).

- Vs is the vessel speed (continuous). It represents the velocity of a boat in each position at a certain time.

- Wd is the water depth or bathymetry (continuous). It represents the depth of the water (in metres). Bathymetry data can also include features such as underwater slopes and terrain.

- Sb is the sea bottom type (categorical, e.g., sandy, muddy, rocky, natural or artificial reef structures).

- Rd is the number of AIS records/day (continuous). It represents the number of AIS records or pings received from the vessel per day.

Appendix A.2. Allocation of the Type of Activities (Dependent Variable)

References

- Alcover, A., Alemany, M., Jacob, M., Payeras, M., García, A., & Martínez-Ribes, L. (2011). The economic impact of yacht charter tourism on the Balearic economy. Tourism Economics, 17(3), 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A., & Mayor, A. (2023). Geomythology, caves, and tourism: History and future perspectives. International Journal of Tourism Anthropology, 9(2), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apps, K., Dimmock, K., Lloyd, D. J., & Huveneers, C. (2017). Is there a place for education and interpretation in shark-based tourism? Tourism Recreation Research, 42(3), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L., & Burton, M. (2017). Proximity and animal welfare in the context of tourist interactions with habituated dolphins. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(2), 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann-Vargas, P., van Koppen, C. S. A., & Lamers, M. (2022). A social practice approach to nature-based tours: The case of the Marble Caves in Northern Patagonia, Chile. Journal of Ecotourism, 21(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, A. P., Cesário, M., & De Noronha, M. T. (2017). Pull attributes of the Algarve: The tourists’ view. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(1), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, J., Lopes, F., Calado, H., & Dearden, P. (2016a). Enhancing satisfaction and sustainable management: Whale watching in the Azores. Tourism Management, 54, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, J., Lopes, F., Calado, H., & Dearden, P. (2016b). Managing marine wildlife tourism activities: Analysis of motivations and specialization levels of divers and whale watchers. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, S. A., Bensi, M., & Copping, A. (2022). AIS-based characterization of navigation conflicts along the US Atlantic Coast prior to development of wind energy. Ocean Engineering, 264, 112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M., & Silveira, L. (2023). Blue planning—A planning model for the development of Blue Tourism in Blue Spaces. Tourism Recreation Research, 49, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., Papathanassis, A., & Vafeidou, M. (2022). Smart cruising: Smart technology applications and their diffusion in cruise tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(4), 626–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, P., Isaksson, O., Maier, A., & Summers, J. (2022). Sampling in design research: Eight key considerations. Design Studies, 78, 101077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Liu, Y., Achuthan, K., & Zhang, X. (2020). A ship movement classification based on Automatic Identification System (AIS) data using convolutional neural network. Ocean Engineering, 218, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C. P., Shen, Y., Kokkranikal, J., & Morrison, A. M. (2023). Understanding British and Danish sailing tourism markets: An analysis based on Kano’s evaluation matrix. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., & Sumaila, U. R. (2010). A global estimate of benefits from ecosystem-based marine recreation: Potential impacts and implications for management. Journal of Bioeconomics, 12, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, F. G., D’Incà, M., Rosso, M., Tepsich, P., di Sciara, G. N., & Moulins, A. (2016). Description of the vessel traffic within the north pelagos sanctuary: Inputs for marine spatial planning and management implications within an existing international marine protected area. Marine Policy, 69, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J., & Davenport, J. L. (2006). The impact of tourism and personal leisure transport on coastal environments: A review. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 67(1–2), 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L., & Stebbins, R. (2011). Serious leisure and nature: Sustainable consumption in the outdoors. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deter, J., Lozupone, X., Inacio, A., Boissery, P., & Holon, F. (2017). Boat anchoring pressure on coastal seabed: Quantification and bias estimation using AIS data. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 123(1–2), 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D. C., Jablonicky, C., Crespo, G. O., McCauley, D. J., Kroodsma, D. A., Boerder, K., Gjerde, K. M., & Halpin, P. N. (2018). Empowering high seas governance with satellite vessel tracking data. Fish and Fisheries, 19(4), 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferter, K., Otterå, H., Christman, M., Kleiven, A. R., Weltersbach, M. S., Gundersen, S., Djønne, C., Bjelland, O., Hartill, B., Lyle, J., Hyder, K., Borch, T., & Vølstad, J. H. (2023). Integrating complementary survey methods to estimate catches in Norway’s complex marine recreational hook-and-line fishery. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 80(1), 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G., Reichel, A., & Shani, A. (2016). Scuba divers: The thrill of risk or the search for tranquility. Tourism Recreation Research, 41(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannier, A. J., Boyer, G., & Gannier, A. C. (2022). Recreational boating as a potential stressor of coastal striped dolphins in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 185, 114222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M., Shi, G., & Li, S. (2018). Online prediction of ship behavior with automatic identification system sensor data using bidirectional long short-term memory recurrent neural network. Sensors, 18(12), 4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudossis, A., & Katsikas, S. K. (2019). Towards a secure automatic identification system (AIS). Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 24, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslinga, J. H., Groote, P., & Vanclay, F. (2017). Using a social-ecological systems perspective to understand tourism and landscape interactions in coastal areas. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(1), 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J. E. S., & Lück, M. (2007). Marine wildlife and tourism management: In search of scientific approaches to sustainability. In Marine wildlife and tourism management: Insights from the natural and social sciences (pp. 1–16). CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Hild, B. O., Jóhannesson, G. T., & Sydnes, A. K. (2023). “Everyone can be a guide until something goes wrong”: Adventure guides’ competencies and tourist safety in the Arctic. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 23, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huveneers, C., Jaine, F. R., Barnett, A., Butcher, P. A., Clarke, T. M., Currey-Randall, L. M., Dwyer, R. G., Ferreira, L. C., Gleiss, A. C., Hoenner, X., Ierodiaconou, D., Lédée, E. J. I., Meekan, M. G., Pederson, H., Rizzari, J. R., van Ruth, P. D., Semmens, J. M., Taylor, M. D., Udyawer, V., … Harcourt, R. (2021). The power of national acoustic tracking networks to assess the impacts of human activity on marine organisms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biological Conservation, 256, 108995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. (2024). Instituto nacional de estatística—Estatísticas do turismo: 2023. INE. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/439494299 (accessed on 14 June 2024)ISSN 0377-2306. ISBN 978-989-25-0683-8. (In Portuguese)

- Jonas, L. C., Botha, N. M., & Myles, P. (2019). A curriculum framework for undergraduate coastal and marine tourism university programs. Tourism in Marine Environments, 14(4), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, T., Dragin, A., Armenski, T., Pavic, D., & Davidovic, N. (2013). What demotivates the tourist? Constraining factors of nautical tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(8), 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. J., Zohoori, S., Hamidi, M., & Wu, X. (2022). Study of narrow waterways congestion based on automatic identification system (AIS) data: A case study of Houston Ship Channel. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Science, 7(6), 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C. (2020). Beyond ‘a trip to the seaside’: Emotional connections, family tourism and psycho-social wellbeing. Tourism Geographies, 24(2–3), 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E., Harcourt, R., & Bradford, W. (2014). Will whale watchers sacrifice personal experience to minimize harm to whales? Tourism in Marine Environments, 10(1–2), 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komninos, A., Kostopoulos, C., & Garofalakis, J. (2022). Automatic generation of sailing holiday itineraries using vessel density data and semantic technologies. Information Technology & Tourism, 24(2), 265–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, M., & Silveira, L. (2018). Nautical tourism in Croatia and in Portugal in the late 2010’s: Issues and perspectives. Pomorstvo, 32(2), 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, G., Melis, G., Rako-Gospić, N., Basta, J., Mackelworth, P., Holcer, D., Atzeni, M., & Leeb, K. (2020). Sustainable dolphin watching tours as a tool to increase public awareness of marine conservation—A comparative analysis between two Mediterranean destinations and implications for management. Journal of Ecotourism, 19(4), 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam-González, Y. E., León, C. J., & De León, J. (2020). Measuring tourist satisfaction with nautical destinations: The effects of image, loyalty, and past destination choice. Tourism in Marine Environments, 15(1), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Corre, N., Saint-Pierre, A., Hughes, M., Peuziat, I., Cosquer, A., Michot, T., & Bernard, N. (2021). Outdoor recreation in French Coastal and Marine Protected Areas. Exploring recreation experience preference as a way for building conservation support. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 33, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoša, N. (2018). When sea becomes home. Annals of Tourism Research, 72, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tixerant, M., Le Guyader, D., Gourmelon, F., & Queffelec, B. (2018). How can Automatic Identification System (AIS) data be used for maritime spatial planning? Ocean & Coastal Management, 166, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Vogel, R., & Viswanathan, N. (2019). Demand for saltwater recreational fishing: A generalized demand approach. Ocean & Coastal Management, 179, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucrezi, S., Milanese, M., Markantonatou, V., Cerrano, C., Sarà, A., Palma, M., & Saayman, M. (2017). Scuba diving tourism systems and sustainability: Perceptions by the scuba diving industry in two marine protected areas. Tourism Management, 59, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, T., & Wozniak, D. (2018). The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tourism Management, 66, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MarineTraffic. (2024). Marinetraffic: Global ship tracking intelligence. Available online: https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/home/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Martínez-Vázquez, R. M., de Pablo Valenciano, J., & Milán-García, J. (2022). Impact analysis of marinas on nautical tourism in Andalusia. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 10(6), 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijles, E. W., Daams, M. N., Ens, B. J., Heslinga, J. H., & Sijtsma, F. J. (2021). Tracked to protect-Spatiotemporal dynamics of recreational boating in sensitive marine natural areas. Applied Geography, 130, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P. V., Salvador, R., & Soares, C. G. (2017). A microcluster approach applied to the case of the nautical tourism sector of the Algarve region (Portugal). Tourism in Marine Environments, 12(2), 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. (2019). Selling Anthropocene space: Situated adventures in sustainable tourism. Anthropocene Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(4), 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M. J., & Otamendi, F. J. (2017). Fostering nautical tourism in the Balearic Islands. Sustainability, 9(12), 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G., Pearce, P., Green, D., & O’Leary, J. T. (2001). Understanding coastal and marine tourism demand from three European markets: Implications for the future of ecotourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9(3), 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C. H., & Roeder, F. (2014). Tourism and Algarve’s underwater heritage valorisation. A case study. Journal of Maritime Research, 11(1), 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, P. D., Serra-Sogas, N., McWhinnie, L., Pearce, K., Le Baron, N., O’Hagan, G., Nesdoly, A., Marques, T., & Canessa, R. (2023). Automated identification system for ships data as a proxy for marine vessel related stressors. Science of The Total Environment, 865, 160987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofri, L., & Nunes, P. A. (2013). Beach ‘lovers’ and ‘greens’: A worldwide empirical analysis of coastal tourism. Ecological Economics, 88, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagel, C. D. (2021). The relevance of skilled in-water guides in swim-with wildlife tours. Tourism in Marine Environments, 16(4), 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagel, C. D., & Lück, M. (2022). #Wildlifeselfies: Insights into the ocular consumption of marine wildlife. Tourism Recreation Research, 49, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paker, N., & Vural, C. A. (2016). Customer segmentation for marinas: Evaluating marinas as destinations. Tourism Management, 56, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassis, A. (2017). Cruise tourism management: State of the art. Tourism Review, 72(1), 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, A., Galin, E., Peytavie, A., Guérin, E., & Gain, J. (2019). Terrain amplification with implicit 3D features. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG), 38(5), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K., Sim, S., & Bae, H. (2021). Vessel estimated time of arrival prediction system based on a path-finding algorithm. Maritime Transport Research, 2, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G. (2021). Family adventure tourism: Towards hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, J., Couto, G., Pimentel, P., & Oliveira, A. (2018). Tourism activities and companies in a sustainable adventure tourism destination: The Azores. Tourism & Management Studies, 14(4), 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyo, N., Filep, S., & Carr, A. (2023). Towards culturally sustainable scuba diving tourism: An integration of Indigenous knowledge. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(3), 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz Neto, A., Lohmann, G., Scott, N., & Dimmock, K. (2017). Rethinking competitiveness: Important attributes for a successful scuba diving destination. Tourism Recreation Research, 42(3), 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, A. M., Asby, P. N. K., Noor, H. M., & Afrizal, T. (2022). Challenges encountered by SMEs in tourism industry: A review from 2017 to 2021. Journal of Asian Behavioural Studies, 7(21), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J., Drakeford, B., Madiedo, A., Costa, J., & Leitão, F. (2024). A bayesian approach to infer the sustainable use of artificial reefs in fisheries and recreation. Sustainability, 16(2), 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. H. (2022). Portuguese artificial reef modules: Are they suitable for dive tourism? In Impact of artificial reefs on the environment and communities (pp. 127–150). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L. M., & Sol Murta, F. (2023). Tourism seasonality management strategies–what can we learn from payment data. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(3), 1205–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, S. W., & Bohnenstiehl, D. R. (2022). Monitoring visitation at North Carolina artificial reef sites using high spatiotemporal resolution PlanetScope imagery. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 55, 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, M. D., Silber, G. K., Adams, J. D., Arroyo, J., Lorenzini, D., Schwehr, K., & Amos, J. (2016). Conservation science and policy applications of the marine vessel Automatic Identification System (AIS)—A review. Bulletin of Marine Science, 92(1), 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D., Marley, S. A., Drakeford, B., Potts, J., & Gullan, A. (2022). The benefits of guide training for sustainable cetacean-based tourism in developing countries, case study–Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve, Mozambique. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 26(4), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J. P., & Notteboom, T. (2013). The geography of cruises: Itineraries, not destinations. Applied Geography, 38, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, J., Kobryn, H., & Newsome, D. (2015). A case study in the evaluation of geotourism potential through geographic information systems: Application in a geology-rich island tourism hotspot. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(3), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N., & Laws, E. (2013). Whale watching—The roles of small firms in the evolution of a new Australian niche market. In Small firms in tourism (pp. 153–166). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, I. P., Gemar, G., Correia, M. B., & Serra, F. (2019). Algarve hotel price determinants: A hedonic pricing model. Tourism Management, 70, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, R., & Benevolo, C. (2022). Towards a new body of marine tourism research: A scoping literature review of nautical tourism. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 40, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Kwortnik, R., Xu, M., Lau, Y. Y., & Ni, R. (2021). Shore excursions of cruise destinations: Product categories, resource allocation, and regional differentiation. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 22, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, R. M. M. (2020). Nautical tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 8(4), 320–330. [Google Scholar]

- Weeden, C., Lester, J. A., & Thyne, M. (2011). Cruise tourism: Emerging issues and implications for a maturing industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 18(1), 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Type | Data | Definition | Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSI | Long Integer | Static | Maritime Mobile Service Identity, unique series of nine digits identifying the vessel | Vessel’s flag |

| Vessel Name | String | Static | The name of the vessel | |

| Vessel Type | String | Static | The type of vessel | |

| Status | Integer | Dynamic | The navigational status reported by the vessel | |

| Speed | Double | Dynamic | The speed of the vessel, in knots | The motion of the vessel according to its speed, drifting or navigating motion |

| Latitude | Double | Dynamic | The geographic coordinates of the vessel | |

| Longitude | ||||

| Heading | Integer | Dynamic | The direction the vessel is facing | |

| Date/Time | Date | Dynamic | The date and time of the record | The season of the year of the record |

| Time |

| AIS Classification | Simplified AIS Classification | Relevant |

|---|---|---|

| Cargo ship | Cargo ship | No |

| Fishing | Fishing | No |

| Passenger | Passenger | Yes |

| Pleasure craft | Pleasure boat | Yes |

| Sailing | ||

| Anti-pollution equipment | Rescue | No |

| Law enforcement | ||

| Medical transport | ||

| Search-and-rescue vessel | ||

| Tug | ||

| Other type | Other type | No |

| No. | Vessel Code | Vessel Type | AIS Pings | Pmax | Days at Sea | Berth Marina | Spot | S | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PA1 | Passenger | 995 | 13 | 131 | Albufeira | A, B | 819 | 176 |

| 2 | PA2 | Passenger | 931 | 13 | 109 | Albufeira | A, B | 855 | 76 |

| 3 | SA1 | Sailing | 499 | 9 | 90 | Faro | C | 470 | 29 |

| 4 | SA2 | Sailing | 469 | 11 | 77 | Faro | C | 461 | 8 |

| 5 | SA3 | Sailing | 203 | 8 | 44 | Vilamoura | C | 199 | 4 |

| 6 | PC1 | Pleasure Craft | 202 | 10 | 45 | Vilamoura | C, D | 202 | 0 |

| 7 | SA4 | Sailing | 102 | 10 | 31 | Vilamoura | C | 102 | 0 |

| 8 | SA5 | Sailing | 97 | 8 | 20 | Olhão | C | 91 | 6 |

| 9 | SA6 | Sailing | 88 | 8 | 20 | Portimão | C, D | 72 | 16 |

| 10 | PA3 | Passenger | 58 | 3 | 42 | Portimão | A, B | 56 | 2 |

| 11 | PC2 | Pleasure Craft | 31 | 4 | 15 | Albufeira | C | 31 | 0 |

| 12 | PC3 | Pleasure Craft | 20 | 4 | 11 | Portimão | C | 20 | 0 |

| 13 | SA7 | Sailing | 19 | 6 | 8 | Albufeira | C | 19 | 0 |

| 14 | SA8 | Sailing | 5 | 3 | 2 | Albufeira | C | 0 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos, J.; Drakeford, B.; Costa, J.; Madiedo, A.; Leitão, F. Tracking Tourism Waves: Insights from Automatic Identification System (AIS) Data on Maritime–Coastal Activities. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020099

Ramos J, Drakeford B, Costa J, Madiedo A, Leitão F. Tracking Tourism Waves: Insights from Automatic Identification System (AIS) Data on Maritime–Coastal Activities. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020099

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos, Jorge, Benjamin Drakeford, Joana Costa, Ana Madiedo, and Francisco Leitão. 2025. "Tracking Tourism Waves: Insights from Automatic Identification System (AIS) Data on Maritime–Coastal Activities" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020099

APA StyleRamos, J., Drakeford, B., Costa, J., Madiedo, A., & Leitão, F. (2025). Tracking Tourism Waves: Insights from Automatic Identification System (AIS) Data on Maritime–Coastal Activities. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020099