Abstract

Cultural heritage plays a critical role in sustaining community identity, particularly in the face of global economic and cultural shifts. This study explores models of heritage management, focusing on community-based tourism (CBT) as a vehicle for sustainable development. Using qualitative interviews with Lithuanian community representatives and a comparative analysis of global frameworks such as the AHC, ANZECC, and EU models, the paper highlights the importance of community engagement, grassroots initiatives, and collaborative governance. Findings reveal that while community-driven efforts can preserve cultural heritage and stimulate local economies, challenges such as limited funding, regulatory barriers, and stakeholder conflicts persist. Recommendations include formalizing organizational structures, leveraging international best practices, and fostering stronger community–government partnerships to balance cultural preservation and economic benefits.

1. Introduction

In the era of globalization, cultures are intermingling and interacting more intensely than ever before. Technological advancements, accelerated migration processes, international trade, and mass media facilitate the dissemination and infiltration of dominant cultures into local communities. Consequently, many traditional cultures face challenges in preserving their authenticity, as cultural assimilation and homogenization become increasingly prevalent. The cultural products disseminated by dominant cultures—music, films, fashion trends, and even social norms—are becoming global standards, overshadowing the unique identities of smaller, local communities.

Cultural heritage is the foundation of a nation’s identity, encompassing historical, social, and economic aspects. However, globalization and economic transformations present significant challenges for heritage protection. Community-based tourism is emerging as a viable alternative that ensures the sustainable development of heritage while allowing local communities to maintain their cultural uniqueness. Despite the internationally recognized role of community-centered tourism (CCT) in cultural protection, numerous obstacles persist. These include regulatory barriers, insufficient funding, and a lack of knowledge or capacity among communities to develop tourism-adapted cultural heritage products. Additionally, the inadequate involvement of government authorities in disseminating essential information further hampers efforts to develop sustainable tourism models.

Paradoxically, an opposing trend has emerged within this context of globalization—tourists increasingly seek authentic experiences and aspire to engage with preserved local cultures. The rapid rise of community-based tourism has become a means not only to safeguard traditions but also to sustainably utilize cultural heritage, generating economic benefits for local communities. However, a crucial question arises: how can mass tourism be managed to prevent the destruction and commercialization of cultural heritage? Every community tourism model must find a balance between economic development and the preservation of cultural authenticity, providing local inhabitants with opportunities for sustainable growth. Community participation in the management of cultural heritage is essential for sustainable economic, social, and environmental development. Various academic studies provide models for this participation, analyzing how involvement can strengthen tourism and heritage initiatives. A recent large-scale bibliometric review by Krittayaruangroj et al. (2023) analyzed 869 Scopus-indexed documents, providing a comprehensive overview of sustainability in community-based tourism (CBT). The study identified three main research directions: eco- and community-based tourism, tourism and sustainable communities, and rural tourism development, emphasizing stakeholder participation, economic sustainability, and environmental responsibility. It also highlighted a shift in research focus from developed to developing countries, reflecting CBT’s growing role in economic diversification and poverty alleviation. The findings confirm CBT’s increasing relevance as a sustainable alternative to mass tourism, underscoring the need for further research on policy frameworks, digital transformation, and governance.

This study aims to assess the experience of Lithuanian communities in developing tourism by using global best practices. The research questions are as follows:

RQ1.

How do communities in Lithuania engage in cultural heritage tourism?

RQ2.

What global heritage management models can be applied locally?

RQ3.

What challenges and solutions emerge in balancing heritage preservation with sustainable development?

Thus, this study explores community-based tourism, emphasizing sustainable tourism strategies that enable the preservation of local cultural heritage. By analyzing various case studies and theoretical frameworks, this study seeks to identify the most effective approaches to reconciling the challenges posed by globalization with the aspirations of local communities to retain their distinctiveness and authenticity.

2. Literature Review: Community-Based Tourism and Heritage Management Models

The management of cultural heritage has become increasingly important in the context of globalization and economic transformation. Community-based tourism (CBT) has emerged as a viable approach that integrates local communities into the sustainable management of heritage assets while generating economic benefits. This section explores the role of CBT in heritage conservation, the governance models that shape these efforts, and the challenges that communities face in balancing tourism development with cultural preservation.

Community involvement in tourism development, commonly referred to as community-based tourism (CBT), has been recognized as a significant approach to fostering sustainable tourism development (Long et al., 2021). It seeks to enhance the well-being of local communities by promoting economic benefits, conserving cultural heritage, and facilitating active participation in decision-making processes (Lopez-Guzman et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023; Lo & Janta, 2020). According to Kim et al. (2023), community-developed tourism strengthens social cohesion and cultural identity by encouraging active participation and empowering local populations.

Manaf et al. (2018) further argue that CBT plays a crucial role in preserving natural resources, safeguarding traditional and cultural values, and fostering socio-economic development through increased community involvement in tourism management and operations. Giampiccoli and Saayman (2018) examined CBT as a mechanism for promoting social justice, empowerment, equitable benefit distribution, and holistic community development. Their study establishes a connection between CBT and the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model, analyzing how community engagement and control over tourism evolve across different developmental stages. As they assert, CBT represents a powerful tool for local economic and social development; however, its effectiveness is contingent upon the community’s ability to maintain control over tourism processes. By reinforcing community engagement and ownership, CBT has the potential to serve as a means for equitable tourism development while simultaneously preserving local cultures and resources.

When communities are adequately supported and provided with the necessary resources, they can effectively manage tourism to protect and enhance their cultural heritage (Tolkach et al., 2023). This approach is not only essential for poverty alleviation but also serves to empower local populations and diversify livelihoods (Rustini et al., 2022). However, CBT initiatives frequently encounter significant challenges, including financial constraints, inadequate infrastructure, and conflicts between local interests and tourism development priorities (Hampton, 2015). To ensure the long-term sustainability of community-based tourism projects, these initiatives must be carefully managed with a continuous focus on preserving and promoting existing community values, despite the obstacles that may arise (Long et al., 2021).

Nonetheless, as Giampiccoli and Saayman (2018) caution, tourism development may also result in negative consequences for local communities. Therefore, active and autonomous community involvement in tourism governance is fundamental to mitigating tourism’s adverse effects and ensuring community well-being. It is important to distinguish that CBT is not simply about participation when such participation is externally controlled or directed by outside actors. Rather, CBT should be understood as a self-participatory process, in which decisions regarding participation, as well as the implementation of tourism initiatives, are initiated, owned, and managed by community members themselves.

Heritage management is a key area for preserving tangible and intangible heritage, promoting cultural tourism and ensuring sustainability. Heritage is a potential attraction that can capture the interest of tourists (Jugmohan et al., 2016). Rustini et al. (2022) highlight the importance of community involvement in every stage of sustainable tourism, from planning to implementation. They point out how community involvement, including physical resources, knowledge, and cooperation, contributes to the effective development of sustainable tourism. Fatina et al. (2023) highlight the importance of multi-sectoral participation in sustainable tourism management by analyzing a case study from Labuan Bajo, Indonesia. Their study highlights that properly coordinated stakeholders can deliver sustainable economic, social, and environmental benefits. Sharma and Bhat (2022) discuss the implications of community participation for social and environmental innovation. They stress that these innovations not only empower local communities but also contribute to long-term sustainability strategies. Sunardi et al. (2021) discuss sustainable tourism models in the new post-pandemic context. They propose an integrated approach that includes socio-cultural, environmental, and economic aspects that promote the well-being of communities.

In Australia and New Zealand, heritage is managed through two important models: the Heritage Risk Management Model of the Australian Heritage Council (AHC), and the Heritage Management Model of the Australia and New Zealand Environment Council (ANZECC). These models reflect different but complementary approaches to heritage management, with a strong emphasis on the role and involvement of communities.

To provide a systematic comparative framework, we established six core analytical dimensions (Table 1) drawn from the cross-national heritage governance literature: (1) community participation intensity, (2) integration of indigenous/traditional knowledge, (3) environmental and climate alignment, (4) institutional support and funding mechanisms, (5) tourism impact orientation, and (6) technology integration. These dimensions allow for a structured comparison across the AHC (Australia), ANZECC (Australia–NZ), and EU models, and create a reference point for analyzing Lithuanian community practices in Section 4.

Table 1.

Heritage management model comparison.

Comparing the ANZECC model with governance examples in the EU, similarities emerge in the areas of sustainability, community participation, and intangible cultural heritage (the transmission of traditions). The ANZECC model emphasizes the integration of environmental sustainability into heritage management. Similarly, EU models of heritage management, particularly under the Faro Convention, promote heritage management as part of long-term environmental protection and societal well-being (Colomer, 2023). Both frameworks emphasize the impact of climate change on heritage to adapt long-term management strategies. The ANZECC model engages communities in the management of natural heritage by promoting eco-tourism and environmental practices. EU models, such as the Faro Convention, encourage citizen participation not only as observers but also as active heritage assessors and managers. ANZECC stresses the importance of local traditions that contribute to the sustainable management of natural and cultural heritage. The EU models do not have this emphasis but draw on local traditions and practices that also enhance the authenticity of heritage. A comparison of these frameworks also reveals differences that emerge at the policy level, e.g., the ANZECC model focuses more on the integration of environmental policy and nature conservation, but policy regulation differs between Australia and New Zealand. In the EU models, heritage management is more often based on general EU legislation and funded through programs such as Creative Europe or Interreg, which strengthen cross-border cooperation. The ANZECC model has a strong focus on natural heritage management, while the EU models balance cultural and natural heritage management, with cultural heritage more often taking priority. Differences also emerge in the use of technology, with ANZECC using environmental monitoring tools such as GIS and climate data analysis. Digitization technologies, such as 3D heritage modelling and digital databases allowing the creation of virtual tourism products, are more common in EU models.

When assessed against these global benchmarks, the two Lithuanian cases demonstrate both convergence and divergence (Table 2). For instance, Antašava Community aligns most closely with the AHC model in terms of informal, grassroots participation but lacks the structured risk assessment tools employed in AHC protocols. In contrast, Stuba Community, with its integration of international heritage networks and use of digital mapping tools, reflects elements of the EU model, particularly in relation to cultural storytelling and public engagement. However, both communities exhibit weak institutional support structures compared to their international counterparts, revealing critical policy and funding gaps at the national level. Unlike ANZECC’s emphasis on ecological heritage, Lithuanian communities remain culturally driven, though climate-related heritage threats are becoming more relevant. The following table consolidates our empirical observations by mapping the Lithuanian communities onto internationally recognized heritage management models.

Table 2.

Lithuanian community alignment with global heritage management models.

This table situates the Lithuanian communities within established global frameworks, providing a comparative lens to evaluate alignment and gaps. Antašava, while rich in participatory and cultural knowledge elements, lacks technological infrastructure and institutional support, placing it closer to the AHC model but without its formal risk management tools. Stuba, by contrast, reflects the influence of EU heritage practices—especially in terms of structured tourism engagement and digital innovation—but still grapples with medium-level sustainability integration and fragmented institutional support. Notably, neither Lithuanian case fully mirrors any single global model, underscoring the need for hybridized frameworks such as the proposed CCHSM (Community-Centered Heritage Sustainability Model), which blends community agency with policy scaffolding and digital innovation.

The following examples of EU heritage management highlight the EU’s ability to integrate communities into heritage management in a variety of ways, from education and heritage narratives to modern technology and international cooperation. The European Heritage Label (EHL) promotes the involvement of communities in cultural heritage activities and reinforces a common European identity. The project integrates citizens into dialogues about heritage and its values but faces challenges in terms of public recognition (Ceginskas & Kaasik-Krogerus, 2022). The European Cultural Heritage 2018 (EYCH) initiative promoted the participation of communities to strengthen their links and help integrate heritage into EU policy frameworks. It provided a unique platform for cooperation between EU institutions and local communities (Costa, 2019). The SoPHIA Project, funded by the EU, brought together academics, professionals and policymakers to discuss the quality of heritage conservation interventions, with a particular focus on community participation (Soto, 2021). “The Hornos de la Cal de Morón” heritage project in Andalusia involved communities in the conservation of traditional lime kilns. It highlighted the importance of education and intergenerational communication in heritage conservation (Manaf et al., 2018). The Casa da História Europeia Museum emphasizes the integration of European cultural heritage narratives, promoting a transnational approach and addressing the challenges of reflecting Europe’s complex history (Quintanilha, 2019). Recent EU projects, such as the application of digital tools for heritage conservation, are helping to improve the sustainability of tourism and heritage management. These initiatives, such as 3D scanning and GIS, raise awareness among local communities about the importance of heritage (Bahre et al., 2020). The EU’s external cultural policies actively involve communities in heritage projects that combine tradition and modern values. This approach helps to build international cooperation networks (Groth, 2022).

According to Wijayanti et al. (2023), community perception is a significant factor influencing participation in heritage tourism management. This aligns with previous research suggesting that thematic tourism experiences, authenticity, and storytelling enhance the tourism experience (Park et al., 2019; Sangkaew & Zhu, 2020). However, as Wijayanti et al. (2023) emphasize, rural communities often struggle with financial and human resource constraints, making stakeholder investment and digitalization critical for the long-term sustainability of heritage tourism.

Recent developments in Community Empowerment Theory suggest that sustainable heritage tourism requires the redistribution of power from institutions to grassroots actors. As noted by Tolkach et al. (2023), empowerment in CBT should be multidimensional—economic, psychological, social, and political—where communities control resources and tourism narratives. This aligns with observations in Lithuanian case studies, where community-led heritage initiatives demonstrate varying degrees of agency but are often limited by institutional constraints.

In parallel, stakeholder theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the complex network of actors involved in heritage tourism, including local governments, NGOs, tourists, and communities. The alignment of interests among these stakeholders is critical for achieving both cultural sustainability and economic viability, according to Freeman et al. (2022). The CCHSM model proposed herein operationalizes stakeholder collaboration by identifying trust-based community–government partnerships as foundational mechanisms of sustainable heritage governance.

The reviewed articles show that community participation is a cornerstone of sustainable tourism development, and various models offer practical ways to achieve this goal. Social and environmental innovations, as well as integrated planning, are essential for long-term sustainability.

These global models demonstrate that multi-stakeholder governance, community empowerment, and technology adoption (e.g., 3D modeling) are critical for balancing heritage conservation and economic development. Lithuania can benefit from these approaches while addressing its unique challenges. Effective CBT models ensure that heritage conservation efforts align with local values, economic benefits remain within the community, and cultural integrity is maintained. However, ongoing support and regulatory frameworks are necessary to prevent exploitation, over-commercialization, and loss of local control over cultural assets.

3. Methodological Framework

This study employed a systematic qualitative approach to examine heritage management practices within Lithuanian community-based tourism initiatives, focusing on two distinct rural communities. The methodology combined purposive participant selection with semi-structured interviewing and inductive thematic analysis to capture nuanced insights into grassroots cultural preservation strategies. These theoretical perspectives also informed our research design. We deliberately chose two contrasting community cases—one characterized by a strong, informal, trust-based network and another with formalized stakeholder governance—to examine how differences in stakeholder relationships and social capital affected heritage tourism outcomes. This approach ensured that the analysis could explore the influence of community trust networks and multi-stakeholder dynamics on sustainable tourism initiatives.

Research design and participant selection criteria: The purposive sampling method was informed by the maximum variation criteria from Patton (2015), ensuring diversity in organizational structure, geographic distribution, and tourism engagement strategies. Communities were initially identified through national cultural databases and referrals from regional cultural heritage coordinators. Additional selection criteria included demonstrable engagement with both tangible and intangible heritage assets, allowing for a comparative case approach grounded in stakeholder diversity.

The study utilized purposive sampling to identify communities demonstrating active engagement in cultural heritage tourism, ensuring participants possessed firsthand experience in both heritage stewardship and tourism development. Selection prioritized three dimensions:

- Operational activity: communities with implemented or ongoing tourism projects linked to tangible/intangible cultural assets;

- Management of diversity: variation in organizational formalization levels from spontaneous grassroots initiatives to structured programs;

- Geospatial distribution: representation of different Lithuanian regions with unique heritage profiles.

Two communities were selected through this stratified approach. The first was Antašava Community (Kupiškis District), which exemplified informal, resource-constrained heritage management, maintaining six historical sites through voluntary efforts without institutional support. Their tourism activities centered on self-guided ethnographic trails and seasonal cultural events. The second community was Zapyškis Stuba Community (Kaunas District), which employed formalized management structures influenced by European cultural networks, implementing intergenerational workshop programs and curated craft tourism experiences. Their methodology integrated digital documentation systems for heritage preservation. This strategic selection enabled a comparative analysis of Lithuania’s emergent community tourism models—from organic place-based initiatives to externally informed institutional approaches.

Data collection protocol: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with two key informants, i.e., Neringa Čemerienė (coordinator in Antašava Community) and Daiva Vaišnorienė (cultural project manager in Zapyškis Stuba Community).

The interview framework contained four thematic blocks:

- Organizational structures and decision-making hierarchies;

- Heritage interpretation and tourism product development;

- Community participation mechanisms;

- Sustainability challenges and institutional barriers.

Interview guides were pre-tested with external heritage practitioners and included both closed and open-ended questions. The guide was divided into four thematic blocks: (1) governance and decision-making structures; (2) heritage interpretation strategies; (3) community engagement practices; and (4) sustainability and barriers. Each informant was given an information sheet and signed consent form before interviews, aligning with EU GDPR compliance.

Each 60–90-min interview followed a flexible questioning protocol, allowing spontaneous exploration of critical issues while maintaining focus on core research themes. This methodology balanced standardized data collection needs with the fluid nature of community-led tourism narratives.

Analytical methodology: The thematic analysis process began with verbatim transcription of interview data, followed by close, repeated readings to identify key patterns and contextual nuances. Initial codes were developed inductively, grounded in the participants’ language and the localized meanings expressed in their narratives. These codes were manually organized and refined through iterative cycles of comparison and reflection, which led to the development of conceptual clusters that captured recurring dynamics in community engagement and governance. Through axial coding, overarching themes emerged, revealing structural, cultural, and participatory dimensions of heritage tourism. Analytical decisions and reflections were documented through memo writing, ensuring transparency and critical engagement throughout the process. This methodological design enabled granular examination of community tourism ecosystems while maintaining analytical transparency. The iterative coding process revealed unexpected insights into vernacular conservation practices and informal partnership networks that structured questionnaire approaches might have overlooked.

Analytical credibility measures: To enhance analytical credibility, the research employed multiple strategies to validate findings. Initial themes were discussed with academic peers specializing in qualitative inquiry and heritage tourism, providing critical external perspectives. Furthermore, member checking was conducted through follow-up correspondence with participants, allowing them to confirm the resonance and accuracy of interpretations. Rather than seeking consensus alone, the analysis also incorporated divergent or disconfirming perspectives to avoid thematic overgeneralization. The study followed established principles of qualitative rigor—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability—ensuring that findings were grounded in the lived realities of participants and remained analytically traceable.

Ethical considerations: The study adhered to European Sociological Association guidelines through written informed consent protocols, anonymization of sensitive operational data, and shared analytical ownership agreements with participants. This approach facilitated open disclosure of challenges related to bureaucratic obstacles and intra-community conflicts—topics typically underrepresented in formal tourism development reports.

Methodological limitations: While the in-depth focus on two communities provided valuable insights, it limited the generalizability of the findings. Future studies could enhance analytical breadth by integrating quantitative measures of tourist engagement alongside qualitative community perspectives. The use of the Lithuanian language during interviews required rigorous translation procedures to ensure semantic accuracy and consistency during analysis. This study is positioned as a model-generating case study, underscoring the need for further research utilizing multiple case designs to improve generalizability and contribute to theoretical advancement.

Despite yielding rich insights, the focus on only two communities means the findings cannot be broadly generalized. Future research should therefore expand the analytical scope. For example, cross-national comparative case studies could examine whether the proposed CCHSM (Community-Centered Heritage Sustainability Model) framework holds across different cultural and policy contexts. Employing mixed-methods designs—combining in-depth qualitative case analysis with quantitative measures of stakeholder networks or tourist impacts—would also strengthen the evidence base. Quantitative validation (such as surveys or structural equation modeling across larger samples) could test the relationships between model components. These approaches will enhance the robustness and external validity of the model and inform how community-driven heritage tourism models can be adapted in varied settings.

4. Insights from Interview Analysis

The analysis of interview responses revealed critical insights about community participation in cultural heritage tourism, emphasizing its dual role in preserving cultural assets and driving sustainable development. Key findings demonstrated that active community engagement fostered heritage protection while generating economic benefits, though challenges persisted in balancing preservation priorities with tourism demands. Successful models of collaboration between local stakeholders, authorities, and tourism operators emerged as essential for creating inclusive management frameworks. The research highlighted the need for capacity-building initiatives, equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms, and adaptive strategies to address evolving socio-economic pressures on heritage sites. The tables below detail the results of the interviews.

Community participation in tourism activities: The research findings highlighted the central role of community involvement in managing and promoting cultural heritage tourism. Communities acted as custodians of historical sites, such as the Dominican monastery barn and Adomynė wooden manor, engaging in heritage preservation and tourism-related initiatives. These included gastronomic workshops, local festivals, and cultural education programs that attracted both domestic and international visitors. However, these activities were often constrained by municipal regulations, limiting economic opportunities.

As shown in Table 3, the Stuba community demonstrated innovative engagement strategies, such as interactive creative workshops (music, quilting) and historical storytelling, aimed at increasing community and visitor participation. Their initiatives reflected a broader trend of grassroots tourism development, where communities, rather than centralized authorities, take the lead in shaping heritage tourism experiences. The findings also indicated that heritage sites served dual functions: as cultural tourism attractions and social spaces, hosting funerals, christenings, and local gatherings.

Table 3.

Community participation in tourism activities.

Key community strategies included heritage preservation efforts, such as building conservation and environmental clean-ups, and interactive tourism practices, including educational heritage workshops and digital mapping of cultural sites. By integrating both historical conservation and modern engagement techniques, the communities ensured that heritage remained accessible and meaningful to diverse audiences.

Contribution to heritage protection and enhancement (see Table 4). The study underscored the essential role of tourism in revitalizing cultural heritage, emphasizing that heritage without human interaction remains stagnant. Communities used tourism as a means to preserve and animate historical sites, ensuring that they remained integral to contemporary cultural life. For example, traditions like sutartinės1, which might otherwise be relegated to archives, remained vibrant through live performances and workshops.

Table 4.

Contribution to heritage protection and enhancement.

Heritage storytelling emerged as a powerful tool, not only enriching visitors’ experiences but also fostering local identity and pride. Tourism-related activities prevented cultural sites from becoming passive museum pieces, instead transforming them into living spaces where history continued to evolve. The community’s active participation in events, storytelling, and preservation efforts reinforced the notion that human engagement is key to sustaining cultural significance.

Furthermore, communities successfully balanced preservation with adaptation, maintaining authenticity while ensuring relevance. This approach not only protected heritage assets but also positioned them as sustainable tourism resources.

Models of community involvement: The research revealed that no formalized models of community engagement existed at the time, with most initiatives operating on a spontaneous, grassroots level. While this flexibility allowed for organic growth and localized adaptation, it also presented challenges related to organizational structure and economic sustainability.

Local government engagement was inconsistent, often leading to conflicts over property rights and economic benefits. Communities frequently drew inspiration from international best practices, particularly Dutch and French village models, which emphasize collaborative management and structured local governance.

As seen in Table 5, despite the absence of formal structures, communities demonstrated resilience and adaptability, initiating projects based on personal interest and available local resources. However, the lack of a defined framework hindered long-term sustainability. Intergenerational learning played a key role, as knowledge-sharing between older and younger generations ensured that heritage preservation remained a continuous process.

Table 5.

Models of community involvement.

Benefits of cultural heritage tourism: The study identified three key areas of impact where heritage tourism provided an impact which could be called economic, social, and cultural benefits. These findings are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Benefits of cultural heritage tourism.

First of all, heritage tourism generated economic benefits. Communities generated modest revenue through paid educational workshops (e.g., kite-making, doll-making) and local events. Limited job creation was observed, particularly in communities like Antašava, where full-time roles have emerged within heritage management. Income generated from tourism was reinvested into community initiatives, such as event planning, equipment acquisition, and site maintenance.

Cultural heritage sites served as community gathering places, reinforcing social cohesion and fostering intercultural exchanges. These benefits could be described as social. Events like funerals, christenings, and concerts were often held in historical places, ensuring that they remained integrated into daily life.

The last benefits were cultural benefits. Heritage tourism helped revive and sustain traditions, ensuring that local customs, such as sutartinės and culinary practices, continued to be passed down. Communities also emphasized environmental sustainability, incorporating local produce and traditional agricultural methods into tourism offerings.

Challenges in heritage and tourism management (see Table 7): Despite its benefits, cultural heritage tourism faced significant barriers that threatened long-term sustainability. These included legal restrictions, limited financial and human resources, and conflicts between communities and local authorities. Communities often struggled to obtain economic permissions for heritage site management, limiting their ability to monetize tourism initiatives. Also, communities faced resource constraints caused by the lack of skilled personnel and funding dependencies, which restricted growth. Moreover, the disputes between local institutions and community groups created inefficiencies in tourism development as well as preservation efforts, highlighting the need for sustainable funding and active site management.

Table 7.

Challenges in heritage and tourism management.

Collaboration with authorities and stakeholders: Community–government relations were strained, with misaligned visions and limited trust hindering cooperation. While strong partnerships with local cultural centers and tourism offices enhanced success, dialogue with municipal authorities remained inconsistent.

The research suggested that successful collaborations emerged when partnerships were built on mutual respect and shared objectives. In regions like Kupiškis, breakdowns in communication exemplified the challenges of community-led tourism management. A shift toward structured, relational cooperation could enhance stakeholder synergy and improve project outcomes. It is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Collaboration with authorities and stakeholders.

Improving community roles in sustainable management. To ensure long-term success, communities must adopt structured organizational models. This study recommends defining clear responsibilities to enhance financial transparency and governance and assess community capacity realistically before undertaking economic projects. Also, it is highly valuable to focus on targeted initiatives, leveraging local heritage strengths (e.g., folklore, youth engagement) as well as encourage training programs to build skills in tourism management and entrepreneurship. By strengthening internal organization and focusing on long-term strategies, communities can enhance their role in sustainable heritage management. All these elements are represented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Improving community roles in sustainable management.

Balancing heritage preservation and economic benefits: A critical takeaway from the study was the need to balance economic sustainability with heritage authenticity. Communities must carefully evaluate their capacity for economic expansion while preserving cultural identity. As shown in Table 10, this research suggests that small-scale, high-quality initiatives—such as historical re-enactments, storytelling sessions, and interactive culinary experiences—offer the best approach.

Table 10.

Balancing heritage preservation and economic benefits.

Local history and traditions should remain at the core of tourism offerings, ensuring that development does not come at the expense of authenticity and cultural integrity. Sustainable tourism strategies should focus on leveraging local resources, ensuring that heritage sites continue to serve both economic and cultural functions.

The interview analysis underscores cultural heritage tourism’s dual potential as an economic engine and preservation catalyst when grounded in equitable community participation. Successful models demonstrate that integrating traditional knowledge systems with modern management frameworks yields superior sustainability outcomes compared to externally imposed strategies. Critical challenges persist in institutionalizing participatory decision-making processes and securing long-term funding streams that prioritize heritage integrity over commercial exploitation. Future initiatives require strengthened legal frameworks for community rights recognition, coupled with innovative financing mechanisms that align tourism growth with conservation imperatives. This research advocates for paradigm shifts in heritage governance that position local communities not merely as stakeholders, but as primary authors and beneficiaries of cultural tourism ecosystems.

5. Results

Lithuanian community representatives acknowledged that active participation was crucial for heritage sustainability. However, A-Community lacked formal governance structures, operating in an ad hoc manner. In contrast, S-Community followed structured international models, focusing on heritage education and creative workshops. Heritage protection and sustainable tourism: Both communities viewed tourism as a way to preserve cultural heritage. For A-Community, tourism revitalized historical sites that would have otherwise remained unused. S-Community integrated educational tourism initiatives, ensuring that local traditions remained relevant. Challenges and policy barriers: Lithuanian communities faced severe regulatory restrictions, limiting their ability to generate revenue from heritage sites. Additionally, a lack of human resources and organizational skills impeded long-term sustainability. Cooperation with authorities and stakeholders: while S-Community successfully collaborated with cultural institutions, A-Community struggled with local government cooperation, facing conflicts over property rights and economic benefits.

The analysis highlights the dynamic but complex relationship between community-based tourism and cultural heritage management. While communities like Antašava and Stuba demonstrated innovative approaches, challenges persisted due to legal, structural, and human resource barriers. Community participation in Lithuanian heritage tourism exhibited variations between informal, locally driven initiatives and structured, internationally influenced models. A-Community adopted an organic, grassroots approach to managing cultural sites, such as Adomynė Manor and the Dominican monastery barn. In contrast, S-Community employed a formalized structure inspired by European best practices, incorporating workshops and intergenerational heritage education programs. While both models contribute to cultural sustainability, their long-term viability depends on financial and regulatory support. Tourism serves as a key mechanism for revitalizing heritage sites by ensuring their continued use and relevance. In S-Community, heritage was integrated into educational programs, promoting long-term sustainability. However, several barriers prevented the full realization of sustainable heritage tourism. Stringent legal regulations restricted economic activities within community-managed heritage sites, while financial and human resource limitations undermined the scalability of initiatives. Additionally, conflicts among stakeholders, including municipal authorities and private tourism operators, complicated governance and funding processes, necessitating stronger policy frameworks and cross-sector cooperation.

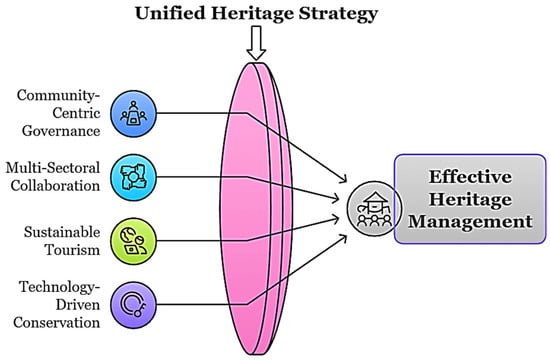

The study revealed that while A-Community thrived on grassroots initiatives, it lacked structure and funding, whereas S-Community benefited from formal governance but faced regulatory barriers. These insights highlight the need for a comprehensive model that balances community participation, governance, sustainability, and technology. The Community-Centric Heritage Sustainability Model (CCHSM) (see Figure 1) integrates these elements, ensuring local engagement while addressing structural and financial challenges. The model is built on sustainable tourism theories and participatory governance principles by aligning with Rustini et al. (2022) and Sharma and Bhat (2022), who highlight the role of communities in tourism-led heritage conservation, reflecting on Fatina et al. (2023) and their multi-sectoral approach to sustainable tourism, and incorporating Sunardi et al. (2021) in proposing a post-pandemic integrated approach for managing heritage and tourism.

Figure 1.

Community-Centric Heritage Sustainability Model (CCHSM).

The model presented emphasizes an integrated approach to heritage management, weaving together community participation, multi-level governance, sustainable tourism, and technology. This holistic framework fosters a dynamic, adaptable system that connects local, national, and international policy frameworks to promote cultural sustainability while simultaneously maximizing economic and social benefits.

At its core, the model prioritizes community-centric governance, where local communities are not passive beneficiaries but active agents in identifying, conserving, and managing heritage. Through empowered local participation, communities engage directly in decision-making processes related to heritage conservation, ensuring their voices shape outcomes that reflect their cultural values. Decentralized management structures further enhance this approach, with local authorities collaborating closely with community organizations to oversee heritage policies and develop tourism strategies that align with local needs. To support this, capacity-building initiatives are integral, offering training and educational programs designed to strengthen community expertise in heritage preservation and tourism management. This emphasis on building local capacity and decentralized decision-making aligns with community empowerment theory and social capital concepts: by devolving authority and nurturing trust-based networks, communities gain greater agency and cohesion in managing their heritage.

The model also highlights the importance of multi-sectoral collaboration and policy integration. Public–private partnerships play a crucial role, bringing together local governments, non-governmental organizations, businesses, and international heritage bodies to foster diverse perspectives and resources. Regulatory frameworks within this model are designed with flexibility in mind, aligning with global heritage conventions such as the Faro Convention, UNESCO guidelines, and ANZECC, while remaining adaptable to regional and local contexts. Cross-border cooperation is encouraged, particularly for heritage sites that hold shared historical significance across nations, facilitating collaborative conservation efforts and joint funding initiatives. Such multi-sector collaboration directly reflects stakeholder theory, which highlights the need to align diverse actors’ interests—from local governments and NGOs to businesses and residents—to achieve sustainable heritage outcomes.

Sustainability, particularly in the context of heritage and tourism, is a foundational principle. The model advocates economic sustainability by ensuring that revenue generated from heritage tourism is reinvested directly into local development projects, infrastructure improvements, and ongoing conservation efforts. Simultaneously, it stresses the importance of environmental and cultural preservation through proactive measures designed to prevent the negative impacts of over-tourism, maintaining the authenticity and integrity of heritage sites. Community-owned tourism initiatives are also promoted, where local stakeholders manage small-scale tourism enterprises, ensuring that economic benefits remain within the community and contribute to its long-term prosperity. This triple-bottom-line approach embodies core principles of sustainable tourism, balancing economic viability with environmental stewardship and cultural integrity to ensure long-term benefits for both the community and heritage sites.

Technology serves as a transformative tool within this model, enhancing both conservation efforts and community engagement. Digital heritage documentation techniques, including GIS mapping, 3D scanning, and virtual reconstructions, are employed to preserve and increase accessibility to cultural sites. Real-time monitoring systems, supported by advanced data analytics, provide critical insights into climate and environmental risks, enabling proactive management of heritage sites. Additionally, interactive platforms such as augmented reality (AR) applications and digital storytelling methods offer immersive cultural experiences, enriching heritage education and fostering a deeper connection between people and their cultural history. Moreover, technology in this model not only aids preservation but also facilitates stakeholder collaboration and builds social capital, since digital platforms and data-sharing increase communication, trust, and collective problem-solving among community members and their partners.

Overall, this model represents a comprehensive and adaptive strategy for heritage management that integrates the strengths of community involvement, governance, sustainability, and technology to safeguard cultural heritage for future generations. Also, while existing models provide governance frameworks for community-based heritage management, they often lack adaptability to localized socio-economic and policy conditions. The proposed model addresses this gap by integrating grassroots participation, adaptive policy mechanisms, and digital innovations, offering a dynamic and scalable approach to sustainable heritage tourism.

The model was developed through a comparative analysis of existing global frameworks and the empirical data gathered from Lithuanian case studies, ensuring that it is both academically grounded and practically adaptable. It highlights how communities can move beyond passive preservation to actively engage in heritage management, supported by decentralized governance, multi-sector collaboration, sustainable tourism strategies, and technological innovations. Key recommendations include the following:

- Developing formalized governance structures to improve accountability and funding mechanisms.

- Strengthening community-government partnerships to overcome regulatory barriers and foster mutual trust.

- Leveraging technological tools (e.g., GIS, 3D modeling) for enhanced conservation and interactive public engagement.

- Promoting sustainable tourism practices that ensure economic benefits remain within local communities, reinforcing cultural identity and resilience.

6. Discussion

Future research on community-based heritage tourism management should expand upon several key themes identified in this study, particularly in relation to partnership dynamics, economic sustainability, digital transformation, and policy integration. These elements are crucial for developing a comprehensive governance model that ensures both cultural preservation and economic viability.

One major research avenue is the evaluation of partnership dynamics between community groups, local authorities, and external stakeholders, such as NGOs and tourism agencies. Findings suggest that cooperation models vary significantly depending on institutional support, regulatory structures, and the extent of local autonomy. Future studies should explore formalized governance structures that promote transparent decision-making and equitable economic benefits, particularly in the Lithuanian context where community-led tourism remains highly informal. Further research could apply comparative analysis with established European heritage management frameworks, such as the Faro Convention and EU cultural policy initiatives, to assess how international best practices could be adapted to Lithuania’s heritage tourism landscape.

Another critical area for exploration is the economic sustainability of community-led heritage tourism. This study underscores that while grassroots tourism initiatives generate economic benefits, these often remain fragmented, seasonal, and difficult to scale. Research should examine long-term funding models, such as public–private partnerships, micro-investment funds, and cooperative business structures, to determine sustainable mechanisms for heritage site management and local entrepreneurship. Additionally, future studies could investigate how heritage-based tourism enterprises balance economic growth with authenticity to prevent over-commercialization and heritage dilution.

The role of digital transformation in heritage tourism also warrants further investigation. Findings indicate that limited technological adoption restricts the scalability and outreach of community-based tourism. While some communities engage in basic digital marketing, most lack access to data-driven decision-making tools, digital storytelling, and interactive heritage experiences. Future research should focus on integrating digital tools such as GIS-based visitor tracking, 3D heritage visualization, and AI-driven tourism analytics to enhance site management, visitor engagement, and adaptive decision-making. Comparative case studies on digital heritage platforms in countries with successful models (e.g., Estonia’s e-tourism initiatives or Scandinavia’s digital museum integration) could provide valuable insights for Lithuania’s tourism sector.

Additionally, policy integration and regulatory frameworks need further examination to ensure that community participation is embedded in national and municipal tourism strategies. Current legal barriers prevent communities from fully leveraging economic opportunities from heritage tourism, particularly regarding commercial activity permissions and property management rights. Future studies should investigate legislative reforms that could foster a more decentralized and participatory heritage management model, allowing communities to take a more active and economically viable role in heritage tourism. Policymakers could benefit from research that evaluates existing governance gaps and suggests pathways for regulatory adaptation.

Finally, interdisciplinary research combining cultural heritage management, sustainable tourism, and participatory governance theories is necessary to build a holistic, evidence-based framework for heritage sustainability. Future investigations could use longitudinal studies to track the evolution of community-based tourism models over time, measuring their socioeconomic impact, resilience to external economic shocks, and long-term viability.

Ultimately, the proposed Community-Centric Heritage Sustainability Model (CCHSM) serves as a comprehensive foundation that synthesizes theoretical insights with practical applications. Future research should refine and expand upon this model by integrating economic, technological, and regulatory dimensions, ensuring the long-term sustainability of cultural heritage while enhancing community well-being and economic resilience.

Linking Empirical Findings to Policy Pathways: The insights from Antašava and Stuba communities point to actionable pathways for policy reform. For example, the grassroots resilience of Antašava, despite lacking formal support, underscores the need for micro-grant mechanisms and legal provisions that authorize community-led economic activity on heritage sites. This directly responds to Lithuania’s current regulatory rigidity, which prevents local groups from monetizing cultural infrastructure.

In contrast, Stuba’s integration into European cultural networks demonstrates the value of policy-backed capacity building, such as intergenerational education programs and creative heritage workshops. These could be scaled nationally through the expansion of programs like Interreg or Creative Europe, which offer platforms for participatory governance and international cooperation.

To institutionalize these insights, we recommend three policy shifts:

- Regulatory modernization—reforming municipal heritage site laws to allow conditional commercial use by certified community associations.

- Capacity-building infrastructure—establishing regional heritage hubs that provide training, digital tools (GIS, 3D mapping), and legal assistance for community tourism initiatives.

- Policy integration with EU frameworks—aligning national heritage strategy with the Faro Convention and SoPHIA quality indicators to ensure participatory and transparent heritage governance.

These recommendations are not abstract extensions but directly arise from observed successes and challenges within the two Lithuanian communities studied. By treating grassroots actors as full governance partners, heritage policy can become more inclusive, responsive, and sustainable.

7. Conclusions

This study highlighted both the potential and challenges of community-based heritage tourism. The experiences of A-Community and S-Community in Lithuania demonstrated that grassroots initiatives could successfully preserve cultural heritage but often struggled with financial sustainability, governance issues, and regulatory barriers. At the same time, structured models inspired by international practices offered stability but faced bureaucratic constraints and dependence on external funding.

The findings suggest that an effective approach must balance community engagement, formal governance, and technological integration. The proposed Community-Centric Heritage Sustainability Model provides a framework that connects local initiatives with broader policy support, incorporating digital tools like GIS mapping and 3D heritage modeling to enhance heritage interpretation and visitor engagement. Economic sustainability remains a key factor, requiring community-driven tourism initiatives that generate local revenue and reinvest in heritage conservation.

To ensure long-term success, communities must develop stronger management structures, improve collaboration with policymakers, and embrace innovative heritage preservation methods. Addressing financial limitations and regulatory constraints is essential for enabling communities to manage their heritage assets effectively. Future research should assess the scalability and adaptability of the CCHSM model across different heritage settings, particularly in regions with varying policy frameworks and economic conditions. Additionally, empirical testing through pilot implementations would help validate its effectiveness and inform policy recommendations. By adopting more integrated and adaptable strategies, heritage tourism can serve as both a cultural preservation tool and a driver of sustainable local development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization V.J. and A.L.-Š.; methodology, V.J.; software, A.L.-Š.; validation, V.J. and A.L.-Š.; formal analysis, V.J. and A.L.-Š. investigation, A.L.-Š.; resources A.L.-Š.; data curation V.J. and A.L.-Š.; writing—original draft preparation V.J. and A.L.-Š.; writing—review and editing, V.J.; visualization A.L.-Š.; supervision, V.J.; project administration, A.L.-Š.; funding acquisition A.L.-Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Exemption was permitted under institutional regulation. The Regulations of the Ethics Committee for Research Compliance at Kauno Kolegija (approved on 10 January 2023) permit exemption when research does not meet the criteria for mandatory ethical review. As outlined in Article 43(d), the Committee may issue the outcome “approval not required” in such cases. Given the study’s methodological scope and thematic content, this exemption applies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHC | Australian Heritage Commission |

| ANZECC | The Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council |

| CBT | Community-based Tourism |

| CCHSM | Community-Centered Heritage Sustainability Model |

| EU | European Union |

Note

| 1 | Sutartinės (lith. sutarti—to be in concordance) is a form of polyphonic music performed by female singers in Northeast Lithuania. The songs have simple melodies, with two to five pitches, and comprise two distinct parts: a meaningful main text and a refrain that may include nonce words. |

References

- Bahre, H., Buono, G., & Elss, V. I. (2020). Innovation embraces tradition—The technology impact on interpretation of cultural heritage. LUMEN Proceedings, 13, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceginskas, V. L. A., & Kaasik-Krogerus, S. (2022). Dialogue in and as European heritage. Journal of European Heritage Studies, 52(3–4), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, L. (2023). Exploring participatory heritage governance after the EU Faro Convention. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 13(4), 856–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S. (2019). European year of cultural heritage-2018: An impressive result to be consolidated. The Journal of Cultural Heritage Studies, 9(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatina, S., Soesilo, T., & Tambunan, R. (2023). Collaborative integrated sustainable tourism management model using system dynamics: A case of Labuan Bajo, Indonesia. Sustainability, 15(15), 11937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Zyglidopoulos, S. C. (2022). Stakeholder theory: Concepts and strategies. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A., & Saayman, M. (2018). Community-based tourism development model and community participation. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7(4), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, S. (2022). Mainstreaming heritages: Abstract heritage values as strategic resources in EU external relations. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 29, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M. P. (2015). Heritage, local communities, and economic development. Annals of Tourism Research, 55, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugmohan, S., Spencer, J. P., & Steyn, J. N. (2016). Local natural and cultural heritage assets and community-based tourism: Challenges and opportunities. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences, 22(1–2), 306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Park, S., & Lee, H. (2023). The role of community-based tourism in sustainable heritage management. Tourism Management, 40, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Krittayaruangroj, K., Suriyankietkaew, S., & Hallinger, P. (2023). Research on sustainability in community-based tourism: A bibliometric review and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(9), 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y. C., & Janta, P. (2020). Resident’s perspective on developing community-based tourism—A qualitative study of Muen Ngoen Kong Community, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, P. H., Huong, T. N., & Lam, T. P. (2021). Community-based tourism: Opportunities and challenges—A case study in Thanh Ha pottery village, Hoi An city, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1926100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Guzman, T., Sanchez-Cañizares, S., & Pavon, V. (2022). Community-based tourism and cultural heritage: A case study. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 573–591. [Google Scholar]

- Manaf, A., Purbasari, N., Damayanti, M., Aprilia, N., & Astuti, W. (2018). Community-based rural tourism in inter-organizational collaboration: How does it work sustainably? Lessons learned from Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Gunungkidul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability, 10(7), 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E., Choi, B. K., & Lee, T. J. (2019). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Quintanilha, I. (2019). Casa da história europeia: Ensaio para uma visita guiada ao museu pan-europeu. Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustini, N. K. A., Budhi, M. K. S., Setyari, N. P. W., & Setiawina, N. (2022). Development of sustainable tourism based on local community participation. International Journal of Economics, Finance, and Management Sciences, 5(11), 3283–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkaew, N., & Zhu, H. (2020). Understanding tourists’ experiences at local markets in Phuket: An analysis of TripAdvisor reviews. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 23(1), 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V., & Bhat, D. A. R. (2022). The role of community involvement in sustainable tourism strategies: A social and environmental innovation perspective. Business Strategy and Development, 5(2), 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, A. (2021). El proyecto europeo SoPHIA reflexiona sobre la calidad de las intervenciones en el patrimonio histórico y cultural. Revista de Patrimonio Histórico, 104, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunardi, S., Roedjinandari, N., & Estikowati, E. (2021). Sustainable tourism model in the new normal era. Linguistics and Culture Review, 5(S3), 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkach, D., King, B., & Pearlman, M. (2023). Community-based tourism: Critiquing the rhetoric of control, empowerment, and self-determination. Tourism Management, 46, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti, A., Putri, E. D. H., Indriyanti, I., Rahayu, E., & Asshofi, I. U. A. (2023). Community-based heritage tourism management model: Perception driving participation. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 12(4), 1630–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).