1. Introduction

The planet is currently experiencing an environmental emergency, often referred to as the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. These crises are predominantly driven by anthropogenic activities such as deforestation, industrialization, poor waste management, urban expansion, tourism (

Drüke et al., 2024;

McKinney, 2019), and economic growth (

Collen, 2014;

Moranta et al., 2022). This alarming situation poses significant threats to ecosystem stability and human well-being, necessitating urgent conservation efforts. Protected areas, including national parks, are indispensable in addressing the triple planetary crisis by mitigating climate change, conserving biodiversity, and preventing environmental degradation.

National parks provide significant ecological benefits, contribute to biodiversity conservation, and offer recreational opportunities (

Newsome & Hughes, 2016). They serve as cornerstones of conservation of natural resources, ensuring the sustainability of ecosystems while supporting tourism and local economies. By fulfilling diverse ecological functions and offering recreational amenities, national parks contribute significantly to both environmental health and social well-being. They can also substantially, as ecotourism destination, enhance national income and positively influence local economies, thereby fostering national economic development (

Ghoddousi et al., 2018).

In Thailand, national parks also hold significant ecological, cultural, and economic values (

Suksawang et al., 2015). It is important to conserve natural resources in national parks for the long-term sustainability of biodiversity, ecosystems, and the services they provide to both nature and society (

IPBES, 2019). In addition to their ecological and economic significance, national parks serve as outdoor classrooms, offering experiential learning opportunities that increase environmental awareness among tourists and local communities. Despite their ecological and economic significance, national parks worldwide face numerous challenges, including inadequate funding, insufficient tourists’ awareness, human-induced pressures, climate change impacts, and the complexities of balancing tourism with conservation (

Ferretti-Gallon et al., 2021;

Miller-Rushing et al., 2021;

Walls, 2022). The management approaches of most national parks, including those in Thailand, tend to react when the issues that have already escalated to unacceptable levels (

Tuntipisitkul, 2012). It is crucial to adopt a proactive approach by conducting studies in advance of dramatic changes or negative impacts. Previous studies indicate that tourists can influence for the conservation efforts (

Ekayani et al., 2019;

Nhamo et al., 2023) and that understanding their willingness to pay for conservation of natural resources and influencing factors can provide conservation insights for better-informed decision making.

Many studies have investigated tourists’ willingness to pay (WTP) for environmental conservation, but the majority have concentrated on a single resource—such as endangered species, biodiversity in general, or ecosystem restoration—rather than evaluating WTP across multiple resource types within the same ecological setting (

Batool et al., 2024;

Getzner et al., 2017;

Schuhmann et al., 2023;

Yang et al., 2022). This narrow scope limits the usefulness of economic valuation for protected area management, where decision-makers must balance diverse conservation priorities with limited resources. A multi-resource valuation approach provides deeper insights into how different ecosystem components are perceived and valued by tourists, allowing for more strategic and targeted resource allocation (

Latip et al., 2020;

Wang et al., 2023). Despite growing interest in the economic valuation of ecosystem services, such integrated approaches remain scarce, particularly in Southeast Asia. Moreover, past studies have often neglected to account for how socio-demographic variables and awareness levels interact with WTP across different resource types. Notably, in the context of Thailand, no existing research has comprehensively assessed tourists’ WTP for multiple natural resources within a single national park. This gap highlights the need for localized and ecosystem-specific studies that better reflect the complex conservation and management challenges faced by Thai national parks.

To address the lack of multi-resource valuation studies in Thai national parks, this study estimates tourists’ willingness to pay (WTP) for the conservation of four distinct natural resources—crab-eating macaques, coral reefs, dry evergreen forests, and clean air—within Khao Laem Ya-Mu Ko Samet (KLYMKS) National Park in Rayong Province, Thailand. This park is well known for its diverse ecosystems and coastal landscapes but faces increasing threats from tourism, climate change, and marine pollution. If left unmanaged, these pressures could lead to biodiversity loss and long-term ecological degradation. By quantifying the economic value of resource conservation using the contingent valuation method (CVM), this study provides data to support evidence-based policymaking for both KLYMKS and other protected areas in Thailand.

The objective of this paper is to assess the economic value that tourists assign to these four natural resources and to examine the socio-demographic and awareness-based factors influencing WTP.

Section 2 presents the methodology, including study site description, sampling size and method, survey design, variables and measurements, and analytical approach.

Section 3 reports the WTP results and regression analysis.

Section 4 discusses the findings and

Section 5 outlines policy implications, while

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

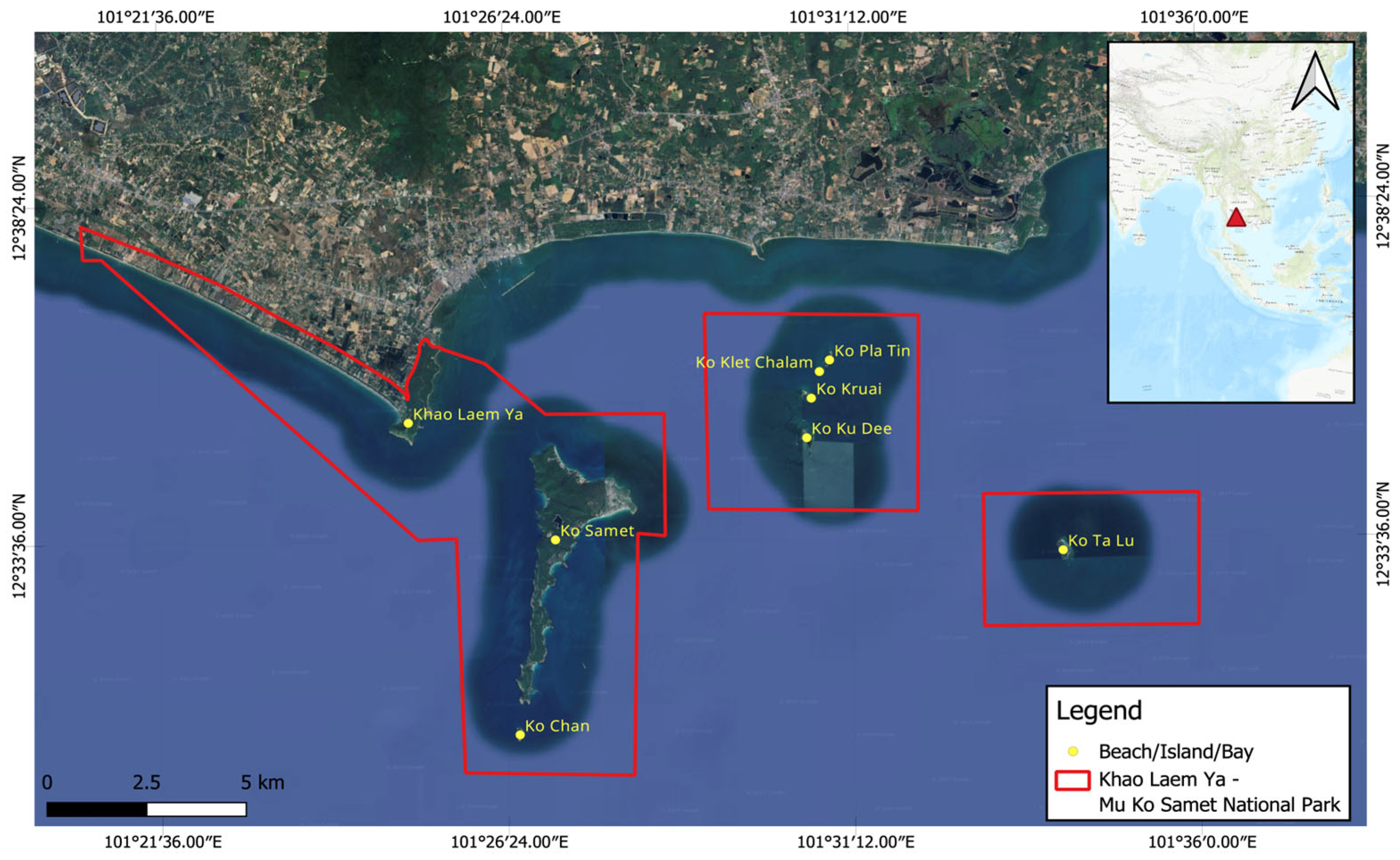

This study is based in Khao Laem Ya-Mu Ko Samet National Park, a marine and coastal protected area located in Rayong Province, Thailand (

Figure 1). The park spans approximately 131 square kilometers (81,875 rai) and was officially designated as Thailand’s 34th national park on 1 October 1981. Managed by the Department of National Park (DNP), the park plays a crucial role in preserving marine and terrestrial biodiversity while serving as a major tourist destination. Situated along the eastern coastline of the Guld of Thailand, the park comprises two main zones: the mainland section, which includes Khao Laem Ya, a coastal hill formation, and Mae Ramphueng Beach, a 12 km sandy shoreline; and the marine section, which encompasses a group of 11 islands, with Ko Samet being the most well-known (

DNP, 2024).

The park’s geographical features are highly diverse, with hilly terrains, sandy beaches, rocky shores, and coral reefs. The park is home to a diverse range of natural resources, including forests, wildlife, marine ecosystems, and freshwater sources. The park’s tropical dry evergreen forests and beach forests sustain a variety of plant species, such as

Pemphis acidula (sea teak),

Terminalia catappa (tropical almond), and

Thespesia populneoides (sea hibiscus). Its wildlife includes 144 species of vertebrates, such as long-tailed macaques, flying foxes, 118 bird species including hornbills and migratory seabirds, and reptiles like monitor lizards and sea turtles (green turtle and hawksbill turtle) (

DNP, 2024). The park’s marine ecosystem is particularly significant, containing coral reefs covering approximately 97 hectares and supporting 42 species of reef fish, seagrass beds, and marine invertebrates (

DNP, 2024). The coral reefs provide habitats for blacktip reef sharks, stingrays, and groupers, making the park vital for marine biodiversity conservation.

This national park was selected as the study area due to its ecological, economic, and cultural significance, which aligns with the research focus on tourists’ willingness to pay for the conservation of natural resources. KLYMKS National Park contains a variety of marine and terrestrial ecosystems—such as coral reefs, dry evergreen forests, and vital wildlife habitats—that support rich biodiversity. It is also one of Thailand’s most visited marine parks, drawing over 1.2 million tourists annually and contributing significantly to the local economy. This high influx of tourists makes it an ideal site to assess visitors’ awareness of natural resources and their WTP for conservation outcomes. Additionally, the park faces environmental pressures from tourism-related activities, necessitating urgent conservation measures and making the park a suitable case study.

Given the park’s extensive biodiversity and ecological resources, this study focuses on four key natural resources, including crab-eating macaques, coral reefs, dry evergreen forests, and clean air, based on their representation of ecosystem diversity, vulnerability to human activities, and direct relevance to tourism. Crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) were selected due to their essential role in forest ecology, particularly in seed dispersal, which contributes to forest regeneration and biodiversity maintenance (

Albert et al., 2013). This species is also classified as endangered on the IUCN Red list, highlighting the urgency of its conservation. Similarly, coral reefs were included due to their status as biodiversity hotspots, supporting marine food chains and coastal protection. However, pollution and damage from tourism threaten their health, making their conservation a priority (

DNP, 2024). Dry evergreen forests were chosen for their crucial role in carbon sequestration, climate regulation, and habitat provision for a diverse range of species (

DNP, 2024;

Terakunpisut et al., 2007). With increasing deforestation and habitat degradation, assessing the conservation value of these forests is critical. Lastly, clean air was included as a key natural resource due to its direct impact on both ecological health and visitor experience. Clean air quality is an essential component of ecotourism, contributing to tourists’ perceptions of a pristine environment, while also playing a role in broader environmental health and climate regulation (

Zajchowski et al., 2019). Overall, these four resources were prioritized over others because they represent both terrestrial and marine conservation challenges and are directly linked to the sustainability of ecosystem in KLYMKS National Park.

2.2. Sampling Size and Method

The sample size for this study was determined using the following Yamane formula, which is a widely used method for calculating sample size when the population size is known.

Here, n is the sample size, N is the population size, and

e is the margin of error. The total number of visitors to KLYMKS National Park in September of the previous year (2023) was 51,401 (

KLYMKS National Park, 2023). By applying this formula using a margin of error (e) of 0.07, the required sample size is calculated to be approximately 190 respondents. However, to account for potential non-responses and to ensure sufficient data are collected, 205 visitors were surveyed.

A convenient sampling method was employed for selection of respondents. This method involved directly approaching tourists who were available and willing to participate at the time of the survey. To achieve a diverse and representative sample, respondents were approached in-person by the researcher and the trained assistants at various key locations such as beaches, visitor centers, and park entry point. Surveys were conducted during peak visitation hours, typically in the late morning and afternoon, across both weekdays and weekends throughout September 2024. Interviewers were stationed at pre-identified high-traffic locations, ensuring systematic coverage of different visitor groups. Tourists were selected on an availability basis, and every effort was made to include participants of varying ages, genders, and nationalities. Interviewers approached individuals or groups at regular intervals, explained the purpose of the survey, and invited them to participate. To reduce potential selection bias, no participant was pre-screened based on specific characteristics, ensuring inclusivity within the practical constraints of the convenience sampling approach.

2.3. Survey Design

Data for this study were collected using a structured survey. The survey targeted adults 18 and above and was administered through face-to-face interviews by the researcher and trained interviewers at key entry points and popular tourist areas within and around KLYMKS National Park in September 2024. To minimize response bias, the interviewers provided clear explanations of the questionnaire content and available response options to each participant, ensuring their full understanding of the questions and scenarios presented to them.

The survey questionnaire comprised of four main sections. The first section (Introduction and Consent) provided respondents with an overview of the study’s objectives and explained their rights, including confidentiality and voluntary participation. A consent statement was included to formally obtain respondents’ agreement to participate in the survey. The second section (Socio-Demographic Information) collected data on respondents’ demographic data such as age, gender, education level, individual monthly income, employment status, nationality, and residential location. The third section (Awareness of Four Types of Natural Resources) assessed respondents’ awareness of crab-eating macaques, coral reefs, dry ever green forests and air quality (clean air) using Likert scale questions, with responses ranging from 1 (not at all aware) to 5 (extremely aware).

The fourth section (Willingness to Pay) applied the contingent valuation method (CVM) using the bidding game format to estimate WTP for the conservation scenarios of four natural resources. This method was selected as it provides more precise estimates, reduces bias compared to the open-ended question format, and is easier to conduct than the payment card approach (

Frew et al., 2004;

McNamee et al., 2010). Respondents were presented with a hypothetical conservation scenario for each resource and asked whether they would be willing to pay the given bid. The bidding amount ranged from THB 0 to 250/year with an equal interval of THB 50. The range and interval of the amounts were set in advance based on the pre-test results. A lower starting bid of THB 50/year was chosen to reduce protect responses and make respondents more comfortable, leading to higher response rates and more reliable WTP estimates. The amount was then raised in increments of THB 50 until the respondents chose the response “no”, at which point the respondent’s WTP was recorded. If the respondent was unwilling to pay any amount, his or her WTP was recorded as the value of zero.

Each of the four resources was assessed separately. For the conservation of crab-eating macaques, respondents were asked if they would be willing to pay 50 THB per year to support a project maintaining the population at 100 individuals instead of allowing a 50% decline. If they agreed, they were asked sequentially about willingness to pay 100, 150, 200, and 250 THB per year. Similarly, for coral reefs, respondents were asked if they would be willing to pay 50 THB per year to maintain the existing 200 hectares of coral cover rather than allowing a 50% decline, with subsequent bid increments following the same pattern. For dry evergreen forest conservation, respondents were asked if they would be willing to pay 50 THB per year to restore 25% of the lost forest cover due to deforestation. In this study, air quality was framed around the Air Quality Index (AQI), with the baseline condition set at an AQI of 50, representing “good” air quality as defined by Thailand’s Pollution Control Department. The air quality scenario assessed whether respondents would be willing to pay 50 THB per year to maintain the park’s current air quality (AQI of 50), with bids increasing progressively if they agreed. In every scenario, it was explained that their answer will have no implication on their future payment. The final section of the questionnaire included open-ended questions and feedback, allowing respondents to provide additional comments or suggestions regarding conservation efforts, followed by a closing statement expressing gratitude for their application.

2.4. Variables and Measurements

The variables included in the regression models are explained in

Table 1. The independent variables included in this study were selected based on their relevance to the study objectives and their established significance in previous studies. Demographic factors (e.g., gender, age, education), socioeconomic factors (e.g., income, employment status), geographic factors (e.g., nationality, residential location), and awareness factors are frequently cited as key determinants of tourists’ WTP for conservation. Regardless of the regression method, the binary independent variables were transformed into dummy variables, and the categorical and ordinal independent variables were converted into binary units. The reference categories used in the models, based on their theoretical importance and to allow meaningful comparisons, were “18–35 years” for age, “female” for gender, “no formal education” for education, “student” for employment status, “no income” for individual monthly income, “Thai” for nationality, “same province” for residential location, and “not at all aware” for awareness levels. The sample size for this study was determined using the following Yamane formula (

Yamane, 1973), which is a widely used method for calculating sample size when the population size is known.

2.5. Analytical Approach

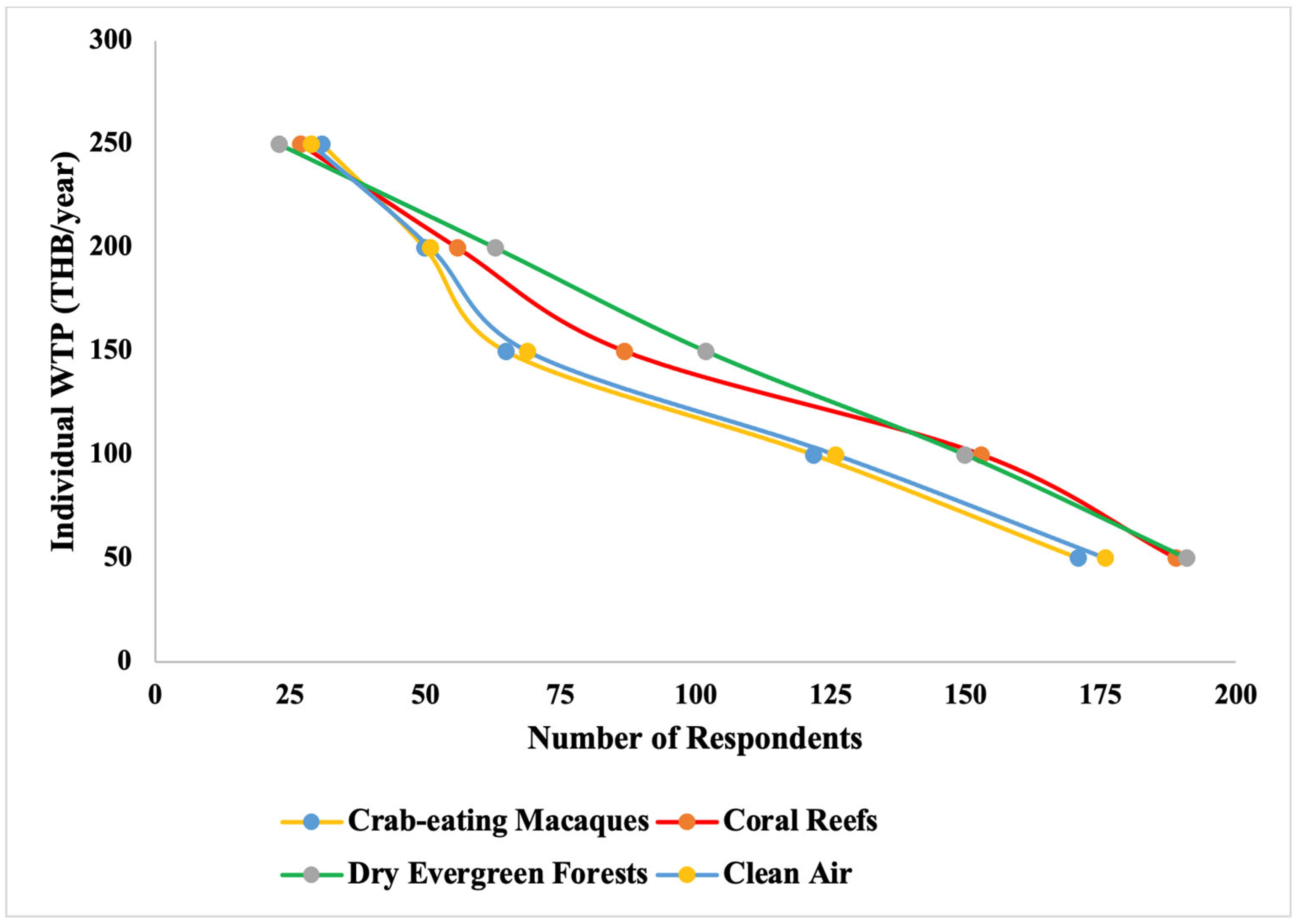

The data analysis was conducted in three parts. First, descriptive statistics were presented to summarize the socio-economic characteristics of respondents, their awareness levels and individual WTP values for each conservation scenario. Each respondent’s WTP was determined based on the highest amount they agreed during the bidding process. The second part involved estimating the aggregate WTP for each natural resource. To derive this estimate, the cumulative “yes” responses from the bidding process were used to construct a demand curve, representing the proportion of respondents willing to pay at each price level. The total WTP for the sample population was computed as the area under this curve, expressed mathematically as follows:

where

Q(

P) represents the proportion of respondents willing to pay at price

P, and

Pmin and

Pmax are the minimum and maximum bid amounts, respectively. To scale the sample-derived WTP to the population level, the aggregate WTP for the sample population was adjusted based on the ratio of population-to-sample, as follows:

This method was applied to each of the four conservation scenarios, providing an estimate the total economic value of conservation for each resource, scaled to the total annual population of visitors.

The third part employed seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) model to analyze of the factors influencing tourists’ WTP for conservation of four natural resources. The SUR model was selected due to its ability to account for the potential correlations between error terms of multiple regression equations, thereby improving the efficiency of the estimations when analyzing multiple conservation scenarios simultaneously. This approach enhances estimation efficiency and provides insights into interdependencies between conservation scenarios. Tests for residual correlations between the error terms of the equations confirmed significant interdependencies, validating the use of this method. The SUR model is expressed as a system of linear equations as follows:

Here,

Yji is the dependent variable representing the ith individual’s response for the jth equation (j = 1,2, …, k).

Xi is a vector of independent variables for the ith individual, shared across all equations.

Βk is a vector of coefficients for the jth equation.

εji is the error term for the jth equation, which is assumed to have contemporaneous correlations across equations, such that the following is true:

In addition,

, where

is the covariance matrix of error of terms.

In this study, a set of four equations can be represented for

k as follows:

Here,

WTPji represents the ith individual’s WTP for the jth conservation scenario.

Xjil represents the lth independent variable for the jth equation, capturing socio-demographic and awareness factors.

Βj0 is the intercept for the jth equation, and Βjl are the coefficients measuring the effect of the lth explanatory variable.

εji is the error term.

This study also tested the variance inflation factor (VIF) to examine the multicollinearity or the extent of correlation among the explanatory factors. VIF values were tested using the following criteria: a VIF value below 3 indicates an ideal level, a value between 3 and 10 is considered acceptable, and a value larger than 10 is deemed unacceptable, signaling high correlation with other variables. When a variable exhibited as highly correlated with other predictors and was subsequently removed. The revised models were tested again for multicollinearity. If no improvement was observed, all variables were reinstated and included in the final regression analysis.

4. Discussion

Resource-specific differences in willingness to pay were evident. On average, individuals were willing to pay THB 129, 125, 110, and 107 per annum for the conservation of dry evergreen forest, coral reefs, clean air, and crab-eating macaque, respectively. The highest WTP for dry evergreen forests reflects their higher perceived value and significance, supported by the lowest proportion of non-payers (7%). Although clean air is a universal good, coral reefs received higher WTP, possibly reflecting their perceived rarity, visibility in tourism marketing, or visitors’ stronger emotional and visual connection with marine biodiversity (

Colléony et al., 2017;

Shoji et al., 2023). Conversely, the crab-eating macaque elicited the lowest WTP and a higher proportion of non-payers (17%), suggesting lower perceived relevance or appeal among tourists. This finding aligns with previous studies (

Amirnejad & Ataie Solout, 2021;

Colléony et al., 2017;

Ihemezie et al., 2021;

Kyrylenko et al., 2024;

Shoji et al., 2023;

Völker & Lienhoop, 2016) that found that those less associated with tangible direct human benefits may garner lower WTP. It suggests a limited appreciation of their ecological role.

A consistent pattern observed in this study is the inverse relationship between bid amounts and the number of respondents willing to pay, as illustrated by the demand curves. This aligns with the economic principle of diminishing marginal utility, which states that as consumption of a particular good or service increases, the total utility grows at a diminishing rate with each additional unit (

Arrow, 1963). The steep decline in WTP at higher bid levels underscores the sensitivity of respondents to pricing, reinforcing the need to balance affordability with conservation objectives.

The aggregate economic values were THB 85,658,537 (USD 2.5 million), THB 99,902,439 (USD 3 million), THB 103,219,512 (USD 3.1 million), and THB 88,000,000 (USD 2.6 million) per annum for conservation scenarios of crab-eating macaque, coral reefs, dry evergreen forest, and clean air, respectively. Compared to the findings from previous studies in similar contexts, the aggregate WTP results in KLYMKS national park comparatively lower. For example,

Navrud and Mungatana (

2018) estimated the annual aggregate economic value of wildlife viewing in Lake Kakuru National Park, Kenya to be between USD 7.5 million and 15 million.

Cruz-Trinidad et al. (

2011) found that coral reefs in Pangasinan, Philippines were valued at approximately USD 38 million per year, substantially higher than USD 3 million estimated for coral reefs in Khao Laem Ya. The low WTP value for clean air may be due to a form of baseline bias, where visitors take clean air for granted in a national park setting, perceiving it as a default or expected environmental condition rather than a distinct and vulnerable resource. Consequently, they may undervalue it relative to more visually striking or endangered features such as coral reefs or dry evergreen forests, which often receive more attention in conservation messaging and ecotourism promotion (

Colléony et al., 2017).

Likewise, the aggregate WTP for forest conservation in Nipa-Nipa Grand Forest Park, Indonesia has an estimate annual value of USD 11.69 million (

Kasim et al., 2024), far exceeding the USD 3.1 million estimated for dry evergreen forests in this study. For air quality,

Kibria et al. (

2017) estimated an aggregate benefit USD 129.94 million per year in Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park, Cambodia, which dwarfs the USD 2.6 million estimated for Khao Laem Ya. The relatively lower aggregate WTP in KLYMKS National Park can be attributed not only to lower individual WTP values but also to the smaller population size in the area. The relatively small population base of the surrounding region limits the potential aggregate valuation, as larger populations, such as those in Kenya. Differences in perceived importance of resources and cultural context further contribute to lower valuations.

SUR analyses identified several factors influencing the willingness to pay of tourists for conservation of four resources. Across all conservation areas, age consistently shows an inverse relationship with willingness to pay, indicating that older respondents tend to pay less (

Aseres & Sira, 2020;

Bhat & Sofi, 2021;

Yang et al., 2022). The decline in WTP by THB 41–49 as tourists transition from the 18–35 age group to older age brackets suggests a generational gap in conservation priorities. The lower willingness to pay among older individuals may be due to a combination of factors, including a reduced sense of personal benefit from long-term conservation outcomes and past experiences of more pristine environments, which may lessen the perceived urgency to act (

Aseres & Sira, 2020). Education also plays a significant role, particularly for coral reefs and dry evergreen forests, where higher levels of education are associated with greater WTP. This positive association corroborates findings by

Bhat and Sofi (

2021),

Srisawasdi et al. (

2021) and

Wilson et al. (

2012). However, the non-significance of education in some models, such as WTP for crab-eating macaque and for clean air (except for postgraduate education), highlights that the impact of education might vary based on the type of resource being conserved.

In terms of employment status, a positive association was observed only with WTP for dry evergreen forest conservation. Specifically, self-employed and unemployed individuals reported higher perceived value than students. This finding is consistent with the previous studies, such as those by

Musa and Shahrudin (

2023), that highlighted the influence of employment status on individual’s willingness to pay for forest conservation. In contrast, employment status was not identified as influential in determining WTP for conservation of other resources such as crab-eating macaque, coral reefs, and clean air. These results suggest that the perceived value of certain resources, such as forest, may vary based on occupational engagement, whereas other resources may elicit more universal support regardless of professional background.

Gender also exhibited the same tendency. Only willingness to pay for conservation of dry evergreen forest was affected by gender, indicating that men are likely to pay more. This is different from trends of the previous findings of

Loft et al. (

2020),

López-Mosquera (

2016), and

Schwartz (

2017) that women perceived current levels of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) funding and have a higher intrinsic motivation for environmental conservation.

Income is another influential factor, particularly for coral reef and dry evergreen forest conservation, where higher income levels correspond with increased WTP. For instance, WTP increased by up to THB 49 for those earning more than THB 50,000 per month. This finding aligns with economic theory and previous studies (

Fauziyah et al., 2023;

Hang et al., 2023;

Imamura et al., 2020) that consistently highlighted that individuals with higher income levels demonstrated greater WTP significantly for coral reef conservation and forest conservation. In contrast, for conservation of crab-eating macaque and clean air, income was not a significant driver to WTP. This discrepancy may stem from differences in individual preferences.

In terms of residential location, certain segments significantly affect WTP across all resources except dry evergreen forest. Tourists from outside of Thailand demonstrated a higher willingness to pay than tourists from same province where KLYMKS National Park is located, particularly for conservation of crab-eating macaque and clean air. For coral reefs conservation, tourists from nearby provinces and international locations perceived a higher value compared to tourists from same province where KLYMKS National Park is located. These findings align with studies by

Liestiandre et al. (

2019) and

Nguyen et al. (

2024), which reported that tourists from farther locations (non-local residents) often exhibited a higher WTP for conservation. As suggested by

Nguyen et al. (

2024), conservation payments by international tourists may be viewed as part of the overall holiday experience and budget, whereas local visitors might perceive them as an added cost, especially under more constrained financial conditions. However, this contrasts with the finding from these previous studies (

Yang et al., 2022).

Nationality displayed a negative influence on WTP for clean air, contradicting the findings that international tourists consistently demonstrated higher WTP than domestic tourists (

Liu et al., 2019;

Perez Loyola et al., 2021). Nationality did not significantly influence willingness to pay for conservation of other resources such as crab-eating macaque, coral reefs, and dry evergreen forest. This suggests that domestic tourists might perceive air quality as a more immediate concern, while foreign visitors prioritize tangible conservation projects such as forests and coral reefs.

Awareness levels emerged as a consistent positive factor in all resources. Except crab-eating macaque where only one awareness level “very aware” has significant effect, WTPs for other resources such as dry evergreen forest, coral reefs, and clean air were influenced by all awareness levels and two awareness levels (“very aware” and “extremely aware”), respectively. Individuals with higher awareness levels perceive higher value. Notably, transitioning from “not at all aware” to “very aware” or “extremely aware” substantially increases WTP. The strong influence of awareness mirrors the findings by

Marzo et al. (

2023) and

Tien et al. (

2024), which emphasized that individuals who are more informed about are likely to perceive higher value.

5. Policy Implications

The economic valuation results underscore the substantial monetary value that tourists assign to the conservation of natural resources within Khao Laem Ya-Mu Ko Samet National Park. These aggregate WTP estimates provide a strong foundation for designing effective conservation financing strategies. Policymakers and park authorities can leverage these figures to secure external funding from government agencies, international donors, and private sector partners by integrating them into grant proposals and conservation investment plans (

Cruz-Trinidad et al., 2011). Additionally, voluntary donation schemes can be introduced at park entrances and kiosks or through digital platforms, giving visitors an accessible way to contribute. Implementing voluntary donation systems at strategic points—such as park entrances, souvenir shops, visitor centers, or online booking platforms—can provide a practical and inclusive mechanism for funding conservation activities. These initiatives are likely to be more effective when paired with tangible illustrations of impact, for example, 100 THB supports the planting of 5 native seedlings or funds one hour of coral reef monitoring. Such messages help make the contribution feel meaningful and transparent to donors. In addition, partnerships with private companies through corporate sponsorship programs can further increase visibility, attract new funding streams, and demonstrate private-sector commitment to environmental stewardship, thereby enhancing public trust and participation.

Innovative mechanisms such as corporate sponsorships, ecotourism levies, and premium conservation passes may also be explored to diversify funding sources and align with visitors’ willingness to pay. The analysis of WTP determinants reveals opportunities to tailor conservation outreach based on visitor profiles. For example, coral reef conservation programs may benefit from targeting educated and high-income groups, as both education and income were found to significantly influence WTP in this study. Awareness emerged as a consistent and strong predictor of WTP across all resources, highlighting the importance of targeted communication strategies to enhance perceived conservation value (

Shoji et al., 2023).

Policymakers are encouraged to prioritize conservation efforts by balancing both the ecological significance and economic valuation of each resource, while also considering the socio-demographic composition of visitors. Integrating these findings into national conservation strategies will help strengthen Thailand’s broader efforts to protect natural resources and promote sustainable tourism in its protected areas (

Suksawang et al., 2015). Beyond economic metrics, non-material values—such as cultural heritage, spiritual connection to nature, and intrinsic appreciation—must be emphasized. Policy frameworks should communicate both tangible costs and intangible benefits to strengthen public support for conservation.

6. Conclusions

This study assessed tourists’ willingness to pay (WTP) for the conservation of four distinct natural resources—crab-eating macaques, coral reefs, dry evergreen forests, and clean air—within Khao Laem Ya-Mu Ko Samet (KLYMKS) National Park in Thailand. Drawing on 205 responses and using the contingent valuation method, the results reveal resource-specific variation in WTP. Dry evergreen forests received the highest average WTP (THB 129/year), while crab-eating macaques garnered the lowest (THB 107/year). When scaled to the park’s annual visitor population, aggregate WTP values reached as high as THB 103 million for forest conservation, reflecting the substantial perceived economic value of ecosystem services.

The seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) analysis identified age and awareness levels as consistent predictors of WTP across all resources, emphasizing the importance of age-sensitive outreach and targeted education campaigns. Other factors—such as education, income, employment status, nationality, and residential location—exhibited resource-specific effects, indicating the need for tailored conservation messaging and engagement strategies. For example, international tourists may be more inclined to view conservation contributions as part of their overall travel experience, while local visitors may face tighter budget constraints.

By employing a multi-resource valuation framework within a single protected area, this study contributes novel insights to the literature. It moves beyond the common one-resource focus to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how tourists perceive and prioritize different ecosystem services. These findings have important implications for sustainable tourism and conservation planning in Thailand and support broader policy responses to the triple planetary crisis—climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution—by positioning ecotourism as a viable mechanism for conservation financing.

Beyond the economic dimension, this research also invites reflection on non-material values associated with nature. While WTP figures provide a practical metric for conservation planning, protected areas also carry profound cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic significance that cannot be easily quantified. Communicating these intrinsic values alongside economic benefits can help build more emotionally resonant and ethically grounded conservation narratives.

The data represent a single time period and do not account for seasonal or long-term shifts in tourist behavior. Future research should consider longitudinal approaches to capture temporal dynamics. Moreover, the analysis focuses solely on tourist perspectives. Incorporating the views of local communities, park staff, and policymakers in future work would offer a more inclusive and adaptive foundation for designing equitable conservation strategies.