Abstract

Natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, or tsunamis can significantly affect the image of tourist destinations and the intention to visit them. However, research on the effects of natural disasters and their impact in destinations in Mexico is an under-researched topic. Moreover, attitudes and behaviors of solidarity are important for recovery of destinations after natural disasters. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine how people’s perceived risk and solidarity attitudes affect the image and intention to visit destinations after natural disasters in the country. Through a structured questionnaire (n = 228), the risk perception, solidarity attitudes, destination image, and intention to visit were measured to assess interest in visiting the emblematic destination of Acapulco, Mexico, which was devastated by Hurricane Otis (category 5) in October 2023. The results show that risk perception does not affect destination image and solidarity attitudes, but it does affect the intention to visit the destination (β = −0.120). The main findings of this study establish the strong influence of solidarity attitudes on the image (β = 0.611) of the destination and the intention to visit (β = 0.581). The results state that destination image had a mediating effect (β = 0.240) on solidarity attitudes and intention to visit post-disaster destinations. Therefore, destination image has a fundamental effect on the formation of attitudes of solidarity for the recovery of destinations after a natural disaster. Solidarity attitudes are of great importance for the destination’s recovery after natural disasters. It is important to prioritize marketing campaigns that recognize these actions of solidarity, on the part of destination management organizations (DMOs) and local governments.

1. Introduction

Tourism image is one of the most competitive tools. It is based on the tangible and intangible attributes of destinations. Therefore, it is essential to create a positive image that includes the expectations of tourists and the image they perceive, as these factors are determinants of the choice and intention to visit in the tourism industry (Chew & Jahari, 2014). However, in destinations that have experienced a natural disaster or crisis, the tourism image may be affected, and risk perception may increase among tourists, who avoid visiting these destinations (Hasan et al., 2017).

Tourism destinations are increasingly facing natural disasters, such as floods, hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions, which significantly damage their image and therefore tourist flows, affecting stakeholders in the tourism industry (Mair et al., 2016). These natural disasters can damage the image and reputation of destinations, with irreparable consequences (Pascual-Fraile et al., 2024).

In the tourism literature, it is important to distinguish between the concepts of crisis and disaster, the former referring to a process of change that generally has negative consequences in destinations; these are usually man-made events that occur gradually over time. On the other hand, natural disasters occur naturally and are unpredictable and uncontrollable events that affect host communities and the tourism industry from an environmental, economic, and social perspective (Cakar, 2021; Wang & Zhai, 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2023). The most recent crisis faced by the global tourism industry was the COVID-19 pandemic, which left a significant impact, as 2020 was listed as the worst year for tourism, causing a decrease of more than 70% in international tourist arrivals in destinations compared to 2019 (Pascual-Fraile et al., 2024).

On the other hand, some of the natural disasters that have affected emblematic tourist destinations include the 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia, Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean, the 2011 earthquakes and tsunamis in Japan, the 2010 volcanic eruption in Iceland (Cakar, 2021), and Hurricane Otis, a category 5 hurricane that formed in a few hours in the Pacific and affected an emblematic destination in Mexico: Acapulco. Natural disasters have a significant impact on tourists’ travel behavior, as they increase perceived risk and therefore decrease visit intentions, as people seek safe environments in destinations (Hasan et al., 2017).

Risk perception is defined as the assessment of potential harm that may threaten people’s health or well-being (Hakim et al., 2021). Perceived risk can be minimized when there is a perception of low risk with high benefits among tourists and is even influenced by age, as occurred in the COVID-19 pandemic, with the adoption of safety measures and social distancing (Hakim et al., 2021). Risk perception is mainly associated with tourists prior to travel and is influenced by factors such as media and population (Xie et al., 2020), while during and after the trip, it can affect experience, satisfaction, loyalty, and intention to return (Hasan et al., 2017).

Likewise, people’s attitudes of solidarity can significantly influence their interest in visiting destinations affected by a natural disaster or crisis (Hakim et al., 2021). Solidarity attitudes refer to the cohesion that exists among individuals in society with the aim of improving the lives of others, especially those in vulnerable situations (Mishra & Rath, 2020). In the tourism industry, solidarity attitudes are reflected in the interest of tourists to visit a destination mainly to support the vulnerable population affected by a natural disaster and contribute to its recovery (Wang & Zhai, 2023). This becomes relevant, as these events affect economic stability and contribute to the closure of businesses and loss of jobs in the tourism sector. Therefore, tourism solidarity becomes relevant to destination recovery, as governments, businesses, and tourists can engage in empathetic actions and behaviors that contribute to destination recovery (Wang & Zhai, 2023; Dolnicar & McCabe, 2022; Josiassen et al., 2024).

Although infrastructure in destinations is devastated after a natural disaster, intangibles remain fundamental to the recovery process, such as the culture and receptive attitudes of local residents and the supportive attitudes and behaviors of tourists, as they help promote positive energy in public opinion and increase visitation intentions among domestic and international tourists (Wearing et al., 2020). However, safety is critical, so tourists will avoid destinations that are perceived as risky or dangerous. Perceptions of safety may positively influence tourists’ solidarity attitudes towards destinations affected by a natural disaster (Simpson & Simpson, 2017), while risk perceptions may decrease solidarity attitudes and even tourists’ image and visit intentions.

The study of the impact of natural disasters on destinations and their relationship with perceived risk, image, and visit intention is a topic that has been studied in tourism literature (Wang, 2017). Some studies establish the change in tourists’ affective responses to destinations and visit intention (Lehto et al., 2013) on perceived image before and after natural disasters (Ryu et al., 2013; Wu & Shimizu, 2020). Other studies determine how travel motivation affects destination image and satisfaction (Tang, 2014) or how risks associated with the destination affect image and visit intention (Wang, 2017). Some studies analyze how previous experiences of tourists or consumers in destinations that have suffered natural disasters influence image and attitudes (Susanto et al., 2024). Susanto et al. (2024) find that government support positively influences the perceived value of the destination after a natural disaster. In the context of solidarity related to the recovery of tourist destinations, most of the research has been conducted from the perspective of local residents, leaving aside the attitudes of solidarity that tourists might have for the recovery of destinations after a disaster. Other authors (Dolnicar & McCabe, 2022; Wang & Zhai, 2023; Kock et al., 2024; Josiassen et al., 2024) note that the study of solidarity in tourism is a little explored topic, especially on the attitudes and behaviors of tourists towards the recovery of destinations that have suffered from natural disasters.

According to Josiassen et al. (2022), there exist limited theoretical frameworks for understanding the formation of solidarity attitudes and behaviors in the tourism literature. This principle stems from the observation that experiencing suffering enhances a sense of belonging to a group when faced with a common threat. This sense of belonging fosters attitudes of solidarity. Josiassen et al. (2022) apply the “place solidarity” model, considering beliefs in a just, dangerous, and socially dominant world as antecedents of solidarity attitudes. The latter is related to the chaos and danger experienced daily and negatively affects the formation of solidarity attitudes. Additionally, these attitudes positively correlate with involvement in actions to support destinations in crisis contexts, which could encourage solidarity tourism (Dolnicar & McCabe, 2022). Josiassen et al. (2023) incorporate the constructs of animosity and affinity in relation to solidarity attitudes and behaviors. Josiassen et al. (2024) extend the “solidarity of place” model by considering perceptions of local government assistance with respect to warmth, competence, and broad-based trust in the formation of solidarity attitudes. However, the application of solidarity models in tourism has not considered the risks associated with destinations affected by natural disasters. Therefore, this research addresses this knowledge gap regarding the relationship between risk perception and solidarity attitudes regarding the image of destinations affected by natural disasters and the intention to visit them.

In Mexico, there are several studies that have analyzed natural disasters, especially hurricanes and their impacts on destinations. For example, Palafox and Gutiérrez (2013) conducted a review of the hurricanes that have affected Quintana Roo, highlighting that at least 14 hurricanes have affected this state from 1955 to 2007. Other examples are the analysis of the risks and vulnerabilities of Cancun, especially with the case of Hurricane Wilma (Mendoza et al., 2015), and the impact of hurricanes on the west coast of Mexico between 2011 and 2015 (Farfán et al., 2018). However, these studies focus on the impacts of hurricanes and the vulnerability of destinations to these natural disasters, without considering the importance of understanding consumer or tourist behavior for the recovery of destinations. The contributions of this study will help the understanding of which factors should be prioritized in destinations affected by a crisis or natural disaster (Josiassen et al., 2022, 2024). Likewise, this research focuses on the domestic tourism market, since in times of crisis or natural disaster, destinations rely heavily on domestic tourism as a tool for survival and recovery, as there is a decline in international tourist arrivals, particularly due to the physical risks perceived in the context of destinations that have experienced these events (Aburumman et al., 2025).

In October 2023, Hurricane Otis (category 5) hit the port of Acapulco, an iconic destination in Mexico since the beginning of the 20th century, which was significantly affected by this natural disaster, leaving serious socio-economic impacts on the destination and damaging its image, which was reflected in the decrease in tourist arrivals, mainly influenced by the perceived risk caused by the hurricane. Therefore, the aim of this research was to study the relationship between risk perception and attitudes of solidarity in the image of post-disaster destinations in Mexico and the intention to visit them.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Risk Perception and Its Influence on the Destination Image and Solidarity Attitudes

Image is a concept that contributes to the formation of tourist attitudes, since it is built from a mental representation of knowledge, beliefs, or global impressions of a tourist destination (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Y. Zhang et al., 2023). Therefore, the destination image is considered as the perception that tourists have of a place, which is built through impressions, beliefs, and ideas about the expected benefits to be obtained during the trip, which can be functional, social, or emotional, among others (Tapachai & Waryszak, 2000; Rindrasih, 2018). The destination image is not static, as it may change according to the stages of the trip; therefore, the image is considered dynamic (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020; Wu & Shimizu, 2020). Some authors (Ruan et al., 2017; Wu & Shimizu, 2020; Carballo et al., 2022) have found that the decision to travel to a destination is strongly related to the destination image.

However, there are changes in the perception of destinations caused by natural disasters or crises, such as risk perception, safety, and reputation, among others, that influence travel behavior. Risk is seen as a perceptual element in the image of destinations, and those places that are perceived as risky will influence tourists’ decision making. Gorji et al. (2023) found that risk perception in tourist destinations influences the formation of cognitive and affective images, which could increase tourists’ risk perception in financial, satisfaction and safety issues, but these influences depend on the profile of the tourist.

On the other hand, Woosnam et al. (2015) found that risk perception could influence tourists’ solidarity attitudes towards destinations that have suffered a natural disaster, highlighting that this is an under-researched area in relation to risk perception in the field of tourism. These authors mention that solidarity can be considered as the bond that unites people in a society as one, which can be through feelings, attitudes, or actions of social cohesion. Solidarity attitudes are associated with human behavior to help others in situations of crisis or fragility, showing interest in the suffering of others with the intention of helping. In the case of tourism, solidarity attitudes are related to tourists’ empathy for local residents and vice versa, especially in destinations affected by natural disasters or crises (Woosnam et al., 2009; Stylidis et al., 2020).

These solidarity attitudes are associated with travel motivations, mainly to support host communities and promote recovery by visiting destinations affected by natural disasters. However, it is possible that the formation of solidarity attitudes depends on the perceived risk in the destination and how safe the place is. For example, the earthquakes experienced in Turkey and Syria in 2023 were catalogued as the disasters of the century in the Middle East, which generated perceptions and attitudes of solidarity from different sectors, from multinational companies to different citizens around the world who showed empathy for the disaster suffered in these countries (Josiassen et al., 2024). These authors (Josiassen et al., 2024) note that positive attitudes of solidarity towards a country or destination affected by a natural disaster or crisis influence the behavior and perceptions of tourists.

Furthermore, Josiassen et al. (2022) established that solidarity influences the intention to visit sites or places affected by natural disasters. However, the perception of local risks at the destination can influence attitudes towards solidarity (Josiassen et al., 2024), especially with regard to supporting and rebuilding the destination to avoid the loss of employees and economic impact at the destination.

In the case of Mexico, its geographical location makes it susceptible to various catastrophic natural events, as it is located in the Ring of Fire, which can lead to high seismic activity, earthquakes, storms and hurricanes. As a result, the iconic destination of Acapulco was affected by Hurricane Otis (category 5), resulting in a slow recovery in terms of leisure visitor arrivals, possibly because the image of the destination was negatively affected by risk perception. For these reasons, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1:

Risk perception negatively influences attitudes of solidarity for visiting a post-disaster destination.

H2:

Risk perception negatively influences the image of a post-disaster destination.

2.2. Risk Perception and Intention to Visit

Risk perception is one of the most important factors in the decision-making process of tourists when choosing a destination (Hasan et al., 2017; Rosselló et al., 2020). The relationship between perceived risk and visit intention behavior in destinations is well documented, especially in places or destinations that are perceived as risky, either due to natural disasters or crises that negatively affect the tourism industry (Hasan et al., 2017; Rosselló et al., 2020).

Intention to visit is a behavioral response that results from the cognitive evaluation that individuals make before traveling to a place or destination. In the case of tourism, intention to visit has been studied as a predictor of behavior before a possible visit or return to the destination (Seetanah et al., 2018; H. Zhang et al., 2018; Carvache-Franco et al., 2023). It has a significant value for destinations as it is related to satisfaction and loyalty, as well as the economic benefits generated by the high demand for the place (Abbasi et al., 2021). Some of the factors that influence the intention to visit or revisit a destination are perceived image, previous experience in the destination, satisfaction, and risk perception (Waheed & Hassan, 2016; Vareiro et al., 2019; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021).

In the case of destinations perceived as risky, some authors have analyzed the behavior of tourists in relation to their intention to visit, such as the study by Carvalho (2022), who found that awareness is an important predictor of tourists’ beliefs and knowledge about the cognitive image (functional and psychological attributes) and the affective image (emotional characteristics), which can positively influence tourists’ intention to visit. Nguyen-Viet et al. (2020) observed that the intention to visit is influenced by the perceived risk of the destination.

On the other hand, Hasan et al. (2017) established that risk can be perceived differently depending on the geographical area, cultural influences, or even previous travel experiences; while some travelers avoid traveling to destinations that are considered risky, others do so to experience emotions and gain risk-based experiences. These authors (Hasan et al., 2017) identified twenty-two dimensions of risk, including physical, psychological, financial, functional, health, social, crime, safety, and natural disaster risks, among others.

In particular, risk perceptions related to natural disasters often have a negative impact on visitation intentions. Rosselló et al. (2020) found that depending on the type of natural disaster occurring in the destination will be the intention to visit, for example, tsunamis, floods, and events related to volcanoes generate a negative perception for visitors. On the other hand, fires, earthquakes, industrial accidents, and storms generate a different perception, depending on the economic cost they represent in the destination. In particular, floods, tsunamis, and hurricanes have a negative impact, but this can be due to damage to infrastructure or a negative image of the destination.

The above shows that the intention to visit a destination affected by a natural disaster depends strongly on the perceived risk that tourists or consumers have about the place, which is mainly influenced by the image projected by the media, social networks, or by the tourists themselves. In the case of Acapulco, which was affected by Hurricane Otis, it is very likely that interest in visiting this destination will be negatively affected by the risk associated with the destination, due to the image projected by the media and the testimonies of affected residents and tourists. Similarly, the risk associated with the intention to visit destinations that have experienced natural disasters in Mexico has not been studied. Therefore, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

H3:

Risk perception negatively influences the intention to visit a post-disaster destination.

2.3. Solidarity Attitudes and Their Influence on Destination Image and Intention to Visit

Solidarity can be considered as the bonds that unite a society through feelings, emotions, attitudes, or behaviors (Woosnam et al., 2015). In the case of tourism, solidarity is a constant emotion in destinations that have experienced some kind of disaster or crisis (Woosnam et al., 2015; Joo et al., 2021), as it reflects the perceptions and attitudes of support among tourists and residents (Li et al., 2024).

Moreover, it is well known that solidarity in post-disaster destinations can contribute to the recovery of the destination through the supportive actions of tourists, especially with their interest in visiting the destination (Hasan et al., 2017; Nguyen-Viet et al., 2020; Dolnicar & McCabe, 2022; Josiassen et al., 2022; Kock et al., 2024). Solidarity tourism is conceptualized as the compassion of individuals and supportive actions towards the tourism industry as a result of observing suffering, in this case as a result of crises or natural disasters in destinations (Kock et al., 2024). Josiassen et al. (2022) refer to this concept of solidarity as “place solidarity”, i.e., supporting actions towards places that need help or support from the population, especially because of wars between nations. Solidarity tourism has been a topic of interest in recent years, especially in the wake of man-made crises, such as the reconstruction of the tourism industry after the COVID-19 pandemic (Hakim et al., 2021; Nautiyal & Polus, 2022), in the general context of wars (Wen et al., 2023), Russia’s war with Ukraine (Josiassen et al., 2022; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2024), or the conflicts in Palestine (Al-Zoughbi, 2023). However, in the context of natural disasters, the application of solidarity models to understand tourists’ attitudes and behaviors on the image of destinations and intention to visit is very limited.

Most of the research on solidarity in the tourism industry has been related to host communities (Wang & Zhai, 2023), especially through emotional solidarity, which focuses on the interaction between residents and tourists (Kock et al., 2024). Joo et al. (2021) found that solidarity has a positive effect on tourism as a post-disaster support action, as it is recognized as a mediator between perceived risk and tourist support. Kock et al. (2024) stated that the study of solidarity in the tourism industry became relevant due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and this theoretical foundation can be extended to other situations that affect the industry, such as natural disasters (hurricanes, earthquakes, or other events). Solidarity is based on actions of support from individuals to an industry, and these actions of support are based on the suffering that the tourism industry may go through, mainly to minimize the economic damage to the destinations. In other words, solidarity in tourism aims to improve the financial and economic situation of the national tourism industry (Kock et al., 2024).

Studies that examine how solidarity contributes to the formation of attitudes and behaviors are scarce in the tourism literature. Kock et al. (2024) developed a scale of solidarity in tourism that has a positive influence on the intention to visit a destination. However, it is important to clarify that this scale was developed in the context of a man-made crisis (COVID-19). Other authors use the construct of “place solidarity” to understand the formation of solidarity attitudes towards places or destinations currently in crisis, highlighting its positive effect on visit intentions as well as on place recommendations (Josiassen et al., 2022, 2024).

Hakim et al. (2021) demonstrated in their study that solidarity attitudes significantly influenced restaurant visit intentions, especially to avoid job losses and business closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, solidarity becomes a great predictor of visit intentions in scenarios of uncertainty generated by crises or natural disasters (Hakim et al., 2021; Josiassen et al., 2022, 2024; Kock et al., 2024) and is fundamental to comprehending consumer and tourist behavior in terms of image and visit intentions in destinations that have suffered a natural disaster, such as Acapulco. In theoretical terms of this research, the attitudes of solidarity reflect support for the tourism industry. Based on the negative impact that the industry has had on the port of Acapulco in Mexico, these attitudes reflect an orientation of support for the destination through the visit to avoid the closure of establishments and further economic damage to the tourism industry. Based on the previous arguments, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

H4:

Solidarity attitudes positively influence the image of a post-disaster destination.

H5:

Solidarity attitudes positively influence the intention to visit a post-disaster destination.

2.4. Destination Image and Its Influence on Intention to Visit

Destination image is defined as the perceptions or impressions that tourists have of a place in terms of expected benefits or values, whether social, emotional, or functional. These perceptions or impressions of tourists have a great influence on tourist behavior, as they affect visit intentions, satisfaction, loyalty, and revisit intentions (Tapachai & Waryszak, 2000). Keller (1993) mentions that the destination image is associated with three sub-dimensions: the first are the attributes, which are the descriptive characteristics related to the brand of the place; the second are the benefits that the consumer will relate to the brand, taking into account its functional and non-functional, symbolic, and experiential attributes; finally, there are the attitudes related to the brand, which is the evaluation that the tourist makes of the place.

According to Afshardoost and Eshaghi (2020), the image of the destination has a significant impact on the tourist’s travel intention. These authors identify different characteristics of destination image that influence travel and revisit intentions, which they describe as general, cognitive, affective, and conative image. The cognitive image is all the perceptions and impressions that tourists have about a destination, generally related to the different attributes of the place (e.g., infrastructure, atmosphere of the place, and economic and political factors, among others) (Michael et al., 2018). The affective image is reflected in the emotions and feelings of tourists or consumers towards the destination, generally influenced by the cognitive image, while the conative image is the behavioral tendency, mainly related to the intention to visit (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020). On the other hand, the overall image of a destination is a holistic perception that considers the affective, cognitive, and conative images (Josiassen et al., 2016).

Ahmed (2023) found that affective and cognitive images have a greater impact on the intention to visit a destination. Through a meta-analysis of 87 studies on destination image, Afshardoost and Eshaghi (2020) established that the general and affective images are the most predictive of tourists’ behavioral intentions. However, when there is a risk factor, image can play an important role in the intention to visit a destination, especially when there is a crisis and uncertainty in the industry (Susanti et al., 2023). The image of a destination that has experienced a crisis or natural disaster is an essential aspect in the decision-making process of tourists regarding their intention to visit the destination. Ryu et al. (2013) studied the differences in tourists’ perceptions of New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina and found that some tourists had negative perceptions after the natural disaster, while others had positive perceptions that would lead travelers to repeat trips to the destination. Chew and Jahari (2014) analyzed the influence of cognitive and affective images on visitation intentions in a post-disaster context in Japan and found a positive relationship between both images and intention to revisit, with affective images having a higher predictive value.

On the other hand, Nguyen and Imamura (2017) analyzed the strategies implemented to change the negative image created in Tohoku, Japan after the tsunami and earthquake that caused great losses in the region. They focused on creating an image for domestic tourists that emphasized nostalgic feelings, and for foreign tourists that focused more on authentic experiences. Likewise, if the image of a destination affected by a natural disaster is not significantly damaged, there may be interest on the part of tourists to visit the destination, but this interest may be heterogeneous, as some tourists may have more negative perceptions than others (Ryu et al., 2013). The description of previous studies shows the great influence that the image of the destination has on the intention of tourists or consumers to visit a destination, for which the following hypothesis has been formulated for the case of analysis of Acapulco affected by Hurricane Otis:

H6:

Destination image positively influences the intention to visit a post-disaster destination.

2.5. Mediating Effect of Destination Image on Solidarity Attitudes and Intention to Visit

Destination image is the mental representation of the tangible and intangible attributes of destinations, which has a strong influence on the intention to visit (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020; Castro-Analuiza et al., 2020). Especially after a natural disaster, image plays an important role in the recovery of the destination, as well as in the attitudes and behaviors of solidarity that people may adopt. If tourists perceive a positive image of the destination, even after the passage of a natural disaster, the intention to visit could increase as support actions, since other people could find themselves in conditions of vulnerability and suffering in the destinations, or for the simple fact of contributing to the recovery of the destination and avoid the loss of jobs and as actions to support the tourism industry (Hakim et al., 2021). Therefore, the image of post-disaster destinations could have a fundamental mediating role in the formation of attitudes of solidarity and the intention to visit. These attitudes should be based on the sense of empathy for the early recovery of the destination.

Previous studies have analyzed the mediating effect of cognitive and affective images on perceived risk and intention to visit post-disaster destinations (Chew & Jahari, 2014), but the application of destination image as a mediating construct on solidarity attitudes and intention to visit has not been explored (Kock et al., 2024; Josiassen et al., 2022). Josiassen et al. (2024) find that perceptions of government warmth and support foster positive perceptions of tourists and thus in the formation of solidarity attitudes. Therefore, if the image of the destination is perceived positively, solidarity attitudes and visit intentions will move in the same direction.

In the case of Mexico, there have been several natural disasters that have affected the image of iconic places in the country. For example, the earthquakes of 1985 and more recently in 2017 significantly formed attitudes of solidarity and support from the population that human chains and the supply of food were given to a greater extent, especially by the hope of finding more people alive in the rubble; that is, the image was positive and favorable mainly to the recovery of lives (Rojas, 2017). In the case of Acapulco and the effects of Hurricane Otis, it is possible that if the image of the destination is positive (mainly due to cognitive and affective attributes), it may contribute to the formation of attitudes of solidarity and interest in visiting the destination. Based on the above, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H7:

Destination image has a mediating effect on solidarity attitudes and intention to visit a post-disaster destination.

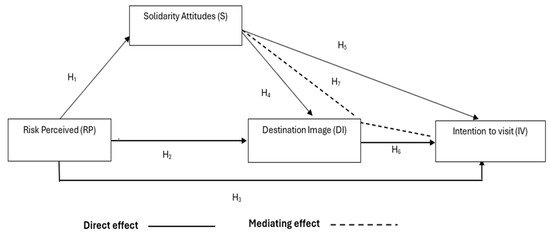

Based on the previous literature review, the following theoretical model was developed to examine the influence of risk perception on solidarity attitudes, destination image and visit intentions, and the effect of solidarity attitudes on destination image and intention to visit. The model establishes seven hypotheses, six of which have a direct effect on the previously described constructs and a mediating effect between solidarity attitudes and visit intentions through destination image (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model that includes the relationships among risk perception, solidarity attitudes, destionation image, and intention to visit.

2.6. Hurricane Otis—Unprecedented Natural Disaster in Acapulco, Mexico

The tourist destination of Acapulco, located in the state of Guerrero (380 km south of Mexico City), is one of the most emblematic destinations in Mexico (Carvache-Franco et al., 2023). It had its heyday after the time of the Mexican Revolution, growing in commerce, industry, and tourism. However, it was not until 1943 that it became an iconic destination for businessmen and artists visiting for business or vacation, due to its natural beauty and constant promotion by the rise of telecommunications in the country. By 1960, it had become a luxury tourist destination that sought to satisfy an international demand (SECTUR, 2014; Carvache-Franco et al., 2023).

The demand for tourism, both international and domestic, lasted for a little over a decade, but between 1970 and 1990, the destination began to deteriorate due to lack of maintenance. In addition, social and security issues and the rise of new sun and beach destinations in Mexico began to put the destination at a disadvantage (SECTUR, 2014; Carvache-Franco et al., 2023). However, despite the increased competitiveness, Acapulco today remains a traditional and iconic destination with a high demand for tourism, especially from domestic tourists.

Due to its geographical location, Acapulco has been affected by several natural disasters, the most recent being Tropical Storm Otis, which unexpectedly became a Category 5 hurricane, the most powerful hurricane and the one that caused the greatest negative economic impact in the Mexican Pacific (Bastien-Olvera et al., 2024; Roy et al., 2024; Hagen, 2024). The hurricane’s impact resulted in six municipalities in the state of Guerrero being declared affected, with the port of Acapulco being the most affected, leading the Mexican government to declare a state of emergency days later. Table 1 highlights some of the major impacts and damages of Hurricane Otis on the Port of Acapulco (UNICEF, 2023; Hagen, 2024).

Table 1.

Main negative consequences of Hurricane Otis in Acapulco.

The effects of the hurricane generated negative social and economic impacts, mainly because the destination is highly dependent on tourism. Months after the impact of the hurricane in Acapulco, the destination continued to recover with the support of the federal government, but the recovery of the destination was slow, coupled with the information that was transmitted in the news, television, and social networks, which affected the image perceived by people, as well as the interest in visiting this iconic destination.

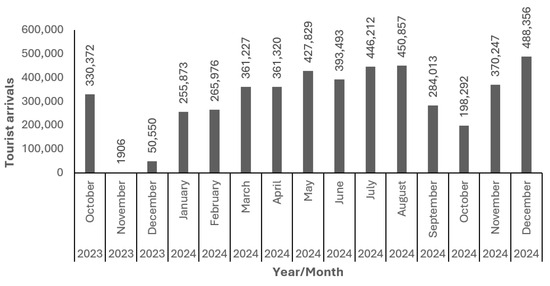

Figure 2 shows the evolution of tourist arrivals in Acapulco from October 2023 (the period in which Hurricane Otis had its greatest impact) to December 2024 (Datatur, 2025). It can be observed that the arrival of domestic tourists after October 2023 had a significant impact, reducing the number of tourist arrivals from 330,372 to 1906 tourists. However, a recovery in tourist arrivals was observed in December 2023, which continued to grow steadily in 2024. The contribution of domestic tourism to the destination should be highlighted, since it represents 90% of tourist arrivals to Acapulco, which is why a recovery in the number of arrivals to the destination is observed in the months of November and December 2024.

Figure 2.

Arrival of tourists in Acapulco from October 2023 to December 2024.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

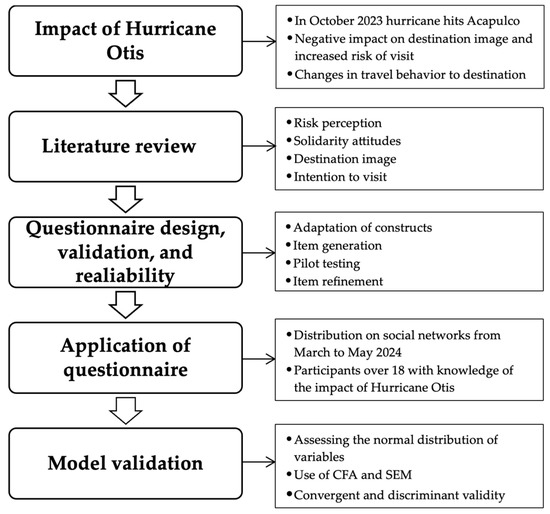

The research approach of this study is briefly described in Figure 3. A questionnaire was designed and distributed through the Google Forms® platform, which was shared on different social networks such as Facebook and WhatsApp, especially among people from central Mexico, due to its proximity to the destination and being one of the main markets of Acapulco. A pilot questionnaire was used with 30 participants to refine the items and improve the instrument (Rojas-Rivas et al., 2020). After revision and correction, convenience sampling was applied, which allows a quick approach to the object of study with reliable results (Guerrero et al., 2010). However, generalization of results is a limitation of this type of sampling. This research does not seek to generalize our findings about natural disasters, but rather to understand how risk perceptions and solidarity attitudes influence the image and intention to visit destinations after a disaster, taking as a case study the emblematic destination of Acapulco in Mexico.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the study’s research approach.

The questionnaire was distributed five months after the impact of Otis in Acapulco, from March to May 2024. The application was considered due to the slow recovery of the destination and for the ease of resources to conduct the research, although the destination started receiving visitors two months after this natural disaster (Echeverría, 2024). Hystad and Keller (2008) conducted their study one year after forest fires that significantly impacted the tourism industry in British Columbia, Canada. They aimed to learn about the intermediate effects of this natural disaster. Wu and Shimizu (2020) examined how a destination’s image changes before and after a natural disaster in Japan. They used three hypothetical models: one, six, and twelve months after the disaster. They found that six months after the disaster, some characteristics of the destination’s image show recovery. However, the perception of the destination remains unfavorable compared to if there had been no disaster. In this sense, the timing of the research is ideal for understanding the short- to medium-term negative impacts of Hurricane Otis, in addition to the fact that the destination’s image and tourist arrivals are beginning to recover.

The inclusion criteria for participants were that they were over 18 years old, had knowledge about the effects of Hurricane Otis in Acapulco, and were interested and available to participate in the survey. The survey was designed and distributed in Spanish, as 90% of the destination’s tourism market is represented by domestic tourism (Hernández, 2025). It is important to mention that the participants gave their electronic consent to participate in the study, indicating that any information shared would only be used for academic purposes.

3.2. Questionnaire and Measurement Scales

The attitudinal questionnaire was composed of four constructs which were adapted from previous studies. The constructs were solidarity attitudes (Hakim et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2024), risk perception (Carvalho, 2022; Kim et al., 2021; Chew & Jahari, 2014; Xie et al., 2020), destination image (Carvalho, 2022; Biran et al., 2014; Ryu et al., 2013; Wang, 2017; Sakti et al., 2021) and intention to visit (Carvalho, 2022; Kim et al., 2021; Chew & Jahari, 2014; Wang, 2017). There were a total of 12 items, with three items per construct (see Table 2). Items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) (Robinson, 2018). Using the Likert scale allows for the measurement of reliability because it is a simple and easy method of responding (Canto de Gante et al., 2020; Table 2). Four authors reviewed the attitudinal statements for linguistic and cultural adaptation.

Table 2.

Constructs and attitudinal statements associated with the questionnaire.

3.3. Data Analysis

Information from the survey was analyzed using SPSS version 23 and AMOS version 23. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated to determine the distribution of the variables. Additionally, the constructs of the questionnaire were confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and their relationships were analyzed with structural equation modeling (SEM). The skewness and kurtosis of the variables were determined; these values should range between −2 and +2 (George & Mallery, 2019) to approximate a normal distribution. Construct validity and reliability were measured using Cronbach’s alpha test (>0.70). According to Kline (2023), there is no simple rule for estimating the sample size in SEM. However, it is recommended to use at least ten cases per analysis variable. In this case, there are twelve variables, meaning the minimum sample size would be 120 cases. Additionally, Kline (2023) points out that the median sample size in SEM studies is 200, assuming a normal distribution of data and no missing values. Therefore, we suggest that the sample size is adequate for SEM procedures.

The structure of the constructs was confirmed through CFA using the maximum likelihood method in AMOS software. The second item of the Destination Image construct was omitted, as the factor loading obtained in the CFA was below the recommended (<0.60). Therefore, it is omitted from the tables of descriptive statistics, CFA and SEM. Moreover, several studies employing SEM retain items with factor loadings between 0.60 and 0.70 (Makhdoomi & Baba, 2019; Choe & Kim, 2021). Mueller and Hancock (2018) state that factor loadings between 0.60 and 0.70 can be employed in CFA and SEM models. Goodness-of-fit indices were used to evaluate the model fit, including the Chi-square test/degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF < 3.0), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI), all of which should exceed 0.90. The Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were also used as measures of model fit (<0.08). Convergent validity of the model was assessed using factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE) (>0.50), and construct reliability (CR) (>0.70) (Wen et al., 2018; Mohamed et al., 2022).

Finally, the proposed theoretical model (H1–H7) was analyzed with SEM. Hypotheses were tested using the t-test (p < 0.05), and standardized regression coefficients were used to determine the relationships between constructs. The discriminant validity of the model was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Ahmed et al., 2023). To analyze the mediating effect of the perceived image of the destination, the bootstrapping method was employed with 5000 samples and a 95% confidence level. Bootstrapping is a resampling technique that provides information about the variability of estimates by repeatedly taking samples from a data set to estimate statistics, construct confidence intervals, calculate standard errors, and perform hypothesis tests.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample and Descriptive Statistics

A total of 228 valid responses were obtained from the questionnaire applied. Table 3 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, which highlight that women’s participation was significantly higher, representing 70.6% of the sample; men represented only 27.6%, and the remaining 1.8% preferred not to give this information. People aged 46 or older represented 42.1% of the sample, followed by those aged 18 to 25 (38.6%). The lowest participation was among participants aged 26 to 35, since this category consisted of only 17 subjects (7.5%).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample studied.

On the other hand, 12.7% of the participants reported a monthly income between MXN 0 and 9999, while 43.9% reported an income between MXN 21,000 and 76,999. When asked if they had visited Acapulco before, 81.6% of the sample said they had. Finally, 61.4% of the sample stayed in hotels, 18% in Airbnb, 10.1% with relatives, and only 8.3% in resorts. Other accommodation options, such as apartments or camping, were mentioned by five respondents (2.2%).

Among the sample, the most relevant construct was Solidarity Attitudes (3.75 ± 1.020), followed by Destination Image (3.71 ± 1.018), Intention to Visit (3.39 ± 1.073), and Risk Perception (2.99 ± 0.953). The reliability and validity of the construct items ranged from 0.746 to 0.893, indicating good construct validity. Additionally, the skewness and kurtosis values of the items are within the established range of −2 to +2, suitable for performing CFA and SEM (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of the items included in the questionnaire.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Model

The CFA was carried out using the maximum likelihood method. For convergent validity, the factorial loadings, AVE, and composite reliability (CR) were estimated. The results show that all items had the factorial loadings greater than 0.60. The AVE was above 0.5 for all constructs, confirming the convergent validity. The composite reliability (CR) ranged from 0.747 to 0.895, which are acceptable indices. The goodness-of-fit indices of the model were adequate: x2/df = 68.202, = 47; CMIN/DF = 1.843; GFI = 0.949; AGFI = 0.909; NFI = 0.950; CFI = 0.976; RMR = 0.057; RMSEA = 0.061; p = 0.000. Likewise, to improve the model, a covariance was established between two errors of the intention to visit construct (IV_1 <-> IV_2) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Confirmatory factorial analysis of the model.

Regarding discriminant validity, the Forner–Larcker criterion was established. According to this criterion, the square root of the AVE of each construct must be greater than the squared correlations between each pair of constructs. As shown in Table 6, this criterion was achieved.

Table 6.

Construct reliability and convergent and discriminant validity.

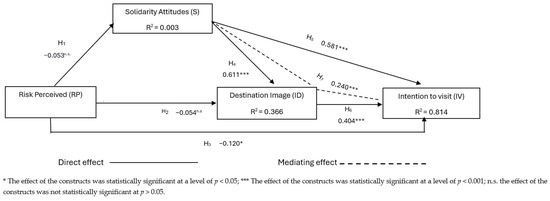

Figure 4 shows the relationship of the proposed constructs using SEM. It is important to note that risk perception does not affect either solidarity attitudes (β = −0.053, p > 0.05) or the image perceived by the survey participants (β = −0.054, p > 0.05). However, risk perception negatively affects visit intention (β = −0.120, p < 0.05), thus supporting the hypothesis. Solidarity attitudes strongly influence perceived destination image (β = 0.611, p < 0.001) and visit intention (β = 0.581, p < 0.001). Additionally, the perceived destination image after a natural disaster positively affects the intention to visit the destination (β = 0.404, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

SEM that includes the relationship between risk perception, solidarity attitudes, destination image, and intention to visit.

Notably, the perceived destination image has a mediating effect on solidarity attitudes and visit intentions (β = 0.240, p < 0.000). According to the proposed model (Table 7), five of the seven hypotheses are supported. Additionally, the model’s constructs have an 81.4% predictive capacity with respect to visit intention, with attitudes of solidarity being the most significant.

Table 7.

Structural equation model.

The results show that solidarity attitudes greatly affect the intention to visit the destination. This indicates that people are more disposed to solidarity when the destination demonstrates actions to safeguard the place, local people, infrastructure, and tourist facilities. This generates a positive effect on visitors, influencing their solidarity attitudes and encouraging them to support the destination’s community. On the other hand, the destination’s image also positively influences the intention to visit, confirming a favorable perception of the place. These results suggest that a positive and resilient image of a destination after a natural disaster can increase solidarity towards its early recovery. Furthermore, these findings suggest that destination management organizations (DMOs) should convey a favorable image of the destination to increase solidarity attitudes and interest in visiting the destination.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

This study examined how risk perception and solidarity attitudes affect the image of destinations in Mexico after natural disasters and the intention to visit them, using Acapulco as a case study. Acapulco is a popular domestic tourist destination in the country. Domestic tourism is one of the most important strategies for destinations to recover after crises or natural disasters, since international tourist arrivals decrease considerably in these circumstances (Aburumman et al., 2025). Destination image is an important element for promotion and recovery. Some studies highlight its importance, particularly when destinations are affected by natural disasters (Chew & Jahari, 2014; Rindrasih, 2018; Wu & Shimizu, 2020). However, unlike previous studies that recognized the negative impact of risk perception on destination image, our findings suggest that risk perception does not influence destination image. This may be because the study was conducted five months after the hurricane impacted the destination, and recovery had already begun, as shown by the graph of domestic and international tourist arrivals to the destination (Figure 2).

The results show that attitudes of solidarity are important in predicting people’s behavior toward destinations affected by natural disasters. Other studies (Hakim et al., 2021; Kock et al., 2024; Josiassen et al., 2022, 2024) have recognized solidarity as supportive behavior toward destinations and their communities affected by crises or natural disasters. This behavior generates support for the destinations’ recovery. Therefore, our results are consistent with previous studies on the importance of tourist solidarity for the recovery of destinations.

Furthermore, the significant impact of the image formed by individuals on their intention to visit has been confirmed, aligning with the findings of Chew and Jahari (2014) regarding the influence of cognitive and affective images on the intention to visit Japan following the natural disaster caused by the Fukushima tsunami. It should be noted that the “destination image” construct adopted elements of the cognitive and affective images of Acapulco for this research. According to Wu and Shimizu (2020), there is a significant change in the tourism image of destinations affected by natural disasters, though the negative impact tends to diminish over time. These authors highlight the positive influence of cognitive and affective images on visit intentions in a natural disaster scenario. However, Carvache-Franco et al. (2023) found that the image of Acapulco strongly influences tourist loyalty; however, this study was conducted in normal conditions. In this case, the results may be related to the fact that the post-disaster image was measured five months after Hurricane Otis hit Acapulco. Consequently, people formed a positive image, which influenced their intention to visit.

Likewise, our research contributes to our understanding of how a destination’s image is key to fostering solidarity in times of crisis or natural disaster, as seen in the 2017 earthquake in Mexico City (Rojas, 2017). This is important in terms of the communication strategies that DMOs should adapt regarding the population’s solidarity actions. This may be because affinity and empathy with the local population and tourism industry contribute to the formation of attitudes and behaviors of solidarity (Josiassen et al., 2024). On the other hand, the positive influence of solidarity attitudes on image and visit intentions is a relevant finding that confirms the results of previous studies, such as those by Josiassen et al. (2024), Wang and Zhai (2023), and Kock et al. (2024). These studies highlight the importance of solidarity in disaster-affected destinations. However, it should be noted that the type of natural disaster that occurred also plays a role, as the attitudes of tourists depend on the nature of the disaster (Rosselló et al., 2020).

5.2. Theoretical Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes the effect of risk perception on destination image and intention to visit destinations that have suffered a natural disaster in Mexico and that have had negative impacts on the tourism industry. The main findings indicate that the perceived risk on the part of the respondents did not influence their attitudes of solidarity or the image formed of the destination. This may be due to the fact that in natural disasters that occur in tourist destinations, solidarity attitudes are strengthened by the population and various actors for the recovery of the destination (Josiassen et al., 2022), strengthening the effects on solidarity behaviors and social cohesion (Hakim et al., 2021).

These findings are an important contribution to theoretical knowledge of tourism, particularly regarding the relationship between the included variables, as few studies analyze solidarity attitudes and behaviors in post-disaster destinations (Josiassen et al., 2024). Most research on solidarity has focused on host communities (Wang & Zhai, 2023) or human-influenced crises (Kock et al., 2024).

On the other hand, Wu and Shimizu (2020) found that there are significant changes in the tourism image of destinations affected by natural disasters. However, the negative impact tends to diminish over time. In the case of Acapulco, this may be related to the emotional response to tourist behavior. Regarding the destination image formed by tourists, we found that risk perception did not affect Acapulco’s image. This may be because tourists are quite familiar with Acapulco and recognize it as an iconic Mexican destination that can recover from natural disasters. In the last 30 years, Acapulco has been affected by hurricanes Paulina (category 4) in 1997, Manuel (category 1) in 2013, Otis (category 5) in 2023, and John (category 3) in 2024 (Romero, 2024). Our results are consistent with previous studies that found destination image greatly influences visit intention (Ryu et al., 2013; Chew & Jahari, 2014; Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020). Therefore, maintaining a positive image, even after a natural disaster, is essential to fostering solidarity and encouraging visits.

5.3. Policy Implications

In terms of policy implications for the recovery of tourist destinations in Mexico affected by natural disasters, it is important to consider the variables analyzed in this study. For instance, DMOs should incorporate solidarity into their recovery strategies by crafting communication messages that foster social cohesion among tourists, visitors, and stakeholders in the tourism industry (Huang et al., 2024). Additionally, when recovering destinations impacted by natural disasters, it is crucial to consider tourists’ perception of risk associated with visiting, as it affects their intention to visit, even if it does not affect the destination’s image. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure the safety of tourists following the impact of natural disasters on destinations in Mexico.

On the other hand, Acapulco is one of the most important tourist destinations in Mexico. It has established itself as a traditional destination within the country (Carvache-Franco et al., 2023). However, it is not exempt from natural disasters, as evidenced by the hurricanes that have impacted the area historically (Romero, 2024). Despite the impact of Hurricane Otis, the results show that the destination’s image is positive. Attitudes of solidarity and support for the destination’s recovery have strengthened, as described in previous studies (Woosnam et al., 2015; Wang & Zhai, 2023; Josiassen et al., 2024). Therefore, it is crucial for federal and state governments to develop public policies that address natural disasters from two perspectives. First, they must prepare tourism stakeholders for natural disasters, such as hurricanes. Second, they must develop strategies to help destinations recover through resilience, marketing, and solidarity actions aimed at businesses, civil society, and stakeholders involved in destination management (Ryu et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2024).

Furthermore, modernizing the tourist facilities and infrastructure could allow for a more efficient recovery of the tourism sector through support funds managed by the federal and state governments (Forster et al., 2012). Therefore, state and municipal governments, business leaders, and tourism agents must work together on tourism planning and management policies to strengthen marketing strategies for the destination’s image. Solidarity actions are essential for the destination’s early recovery, and ensuring safety and addressing other problems such as violence and insecurity are key.

In view of the increase of natural disasters due to climate change, tourism policy and planning for destinations vulnerable to them should be strengthened. In the case of the studied destination, it was hit again by Hurricane John (Category 3) less than a year later, causing severe damage to several areas on the Mexican Pacific coast, including Acapulco. Despite being struck by two hurricanes in less than two years, the destination has demonstrated resilience, with the number of visits recovering in December 2024 (Figure 2).

5.4. Managerial Implications

Due to the impact of Hurricane Otis in Acapulco, the federal government implemented the strategy of holding the Tianguis Turístico 2024, considered the most important tourism fair in Latin America, in April 2024. Businessmen from Mexico, the United States, Colombia, Spain, and other countries attended this edition. The event increased hotel occupancy and promoted various Mexican tourism products (Gobierno de México, 2024). It was considered one of the main strategies for the destination’s recovery (Ortega, 2023). Huang et al. (2024) recommend inviting influencers or public opinion leaders to improve market confidence in the process of communicating about and recovering after the disaster. Strategies that encourage the participation of businesses and governments are therefore fundamental to the recovery of destinations affected by natural disasters.

The results of this research are important for destination management and marketing organizations because communication strategies regarding destinations affected by natural disasters significantly impact the formation of supportive attitudes among visitors and tourists. Government tourism management agencies, such as the Secretary of Tourism of Guerrero and the Secretary of Tourism of Mexico, as well as entrepreneurs, including hotel, restaurant, and travel agency owners, must constantly work to create a destination image that attracts the traditional and family segments of Mexico. Similarly, the international image should emphasize the resilience of the destination in the face of natural disasters (Aleshinloye et al., 2024).

Furthermore, DMOs, including state and municipal governments, as well as the Secretary of Tourism of the State of Guerrero, are encouraged to promote social and solidarity tourism after natural disasters. Results show that solidarity positively impacts the image and intention to visit the affected destination. Based on the variables proposed in this research, it is recommended that tourism managers and government agencies strengthen communication channels through official social media, radio, television, and the press in the event of a natural disaster to promote solidarity tourism further. Additionally, prevention strategies and action protocols should be developed for DMOs and business owners to minimize the impact of natural disasters and risk perception (Pascual-Fraile et al., 2024).

Natural disasters are uncertain and challenging events for destinations, especially due to the unexpected economic damage caused by a lack of tourist arrivals. For example, the impact of Otis in 2023 affected Acapulco’s population and tourist arrivals. Similarly, Hurricane John in 2024 created uncertainty due to its repeated impact on the area. Therefore, stakeholders must consider rapidly rehabilitating infrastructure and business capacity. It is also necessary to strengthen links with small and medium-sized enterprises by creating support networks and providing financing and marketing strategy guidance to ensure the rapid recovery of tourism after a natural disaster.

6. Conclusions

This study examines how risk perception and solidarity attitudes influence the image and intention to visit destinations in Mexico after natural disasters, using Acapulco as a case study. Five of the seven proposed hypotheses are supported by a structural equation model. One of the main findings is that risk perception did not affect destination image and solidarity attitudes. However, the intention to visit was negatively influenced by the perceived risk of Hurricane Otis. The most significant finding is that solidarity attitudes influenced the image and intention to visit post-disaster destinations. This may be due to participants’ familiarity with the destination and their position in the Mexican domestic market.

On the other hand, the strength and resilience of the destination’s image has been demonstrated, as the image formed among the participants was positive. This positive image had a mediating effect on the participants’ attitudes of solidarity with respect to their intention to visit. In other words, the destination’s positive image influences interest in visiting and supporting its recovery. It is important to note that risk management is essential to the destination’s marketing strategies, since it influences the intention to visit.

The information generated from this research is highly relevant to DMOs regarding the post-disaster destination recovery process. It is essential to communicate messages and marketing strategies oriented toward visiting the destination through solidarity tourism. One of the primary actions is therefore to ensure the safety of tourists in scenarios of this nature. These strategies should emphasize the importance of solidarity tourism in the destination’s recovery. Although Mexico’s federal government has the DN-III-E plan to support the armed forces in the event of natural disasters or man-made crises, it is crucial that tourism industry stakeholders also implement disaster prevention strategies, especially in this destination, which has been hit by four hurricanes of varying sizes and impacts in the last 30 years.

Finally, this research presents several limitations that should be considered in future studies. First, the sample was limited to domestic tourists. However, domestic tourism is one of the strategies for destination recovery in the context of crises or natural disasters. Future studies could explore perceived risk and solidarity attitudes among international tourists. Second, the timing of the research is a limitation, so future studies could examine solidarity attitudes at various stages after natural disasters in destinations through longitudinal studies. Future studies may verify whether solidarity attitudes influence other types of natural disasters or destinations affected by man-made crises, such as those affected by narcotrafficking. Additionally, the impact of government and media support on the development of solidarity attitudes should be examined.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.T.-P., E.R.-R., I.C.-M. and L.E.T.-B.; methodology, A.N.T.-P. and E.R.-R.; formal analysis, A.N.T.-P. and E.R.-R.; investigation, A.N.T.-P. and E.R.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.T.-P., E.R.-R., L.E.T.-B., I.C.-M. and J.Z.-A.; writing—review and editing, E.R.-R., L.E.T.-B., I.C.-M. and J.Z.-A.; supervision, E.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the “Professional Productivity and Research Review Committee of the School of Business and Economics” (02/2024; 29 August 2024) of the Universidad de las Américas. Also, the research was guided by the principles of privacy and protection of information of the university, which are based on the “Ley Federal de Protección de Datos Personales en Posesión de Particulares” published in the Diario Oficial de la Federación (https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LFPDPPP.pdf, accessed on 10 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants agreed to participate in the study and were informed that all information provided would be used only for academic purposes, following confidentiality and data protection protocols.

Data Availability Statement

The information used for this research can be provided following a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbasi, G. A., Kumaravelu, J., Goh, Y.-N., & Dara Singh, K. S. (2021). Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Spanish Journal of Marketing—ESIC, 25(2), 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburumman, A., Abou-Shouk, M., Zouair, N., & Abdel-Jalil, M. (2025). The effect of health-perceived risks on domestic travel intention: The moderating role of destination image. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 25(1), 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 81, 104–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. (2023). Destination image and revisit intention: The case of Egypt tourism. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 21(4), 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., Al Asheq, A., Ahmed, E., Chowdhury, U. Y., Sufi, T., & Mostofa, M. G. (2023). The intricate relationships of consumers’ loyalty and their perceptions of service quality, price and satisfaction in restaurant service. The TQM Journal, 35(2), 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosman, K. M., & Joo, D. (2024). The influence of place attachment and emotional solidarity on residents’ involvement in tourism: Perspectives from Orlando, Florida. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(2), 914–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoughbi, L. (2023). Palestinian solidarity tourism: A rapid assessment of host experiences and perceptions. Michigan State University. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien-Olvera, B. A., Rivera, A., Gray, E., Mitchell, S., Favoretto, F., Ezcurra, E., & Aburto-Oropeza, O. (2024). Mangrove preservation could have significantly reduced damages from Hurricane Otis on the coast of Guerrero, Mexico. Science of The Total Environment, 957, 177822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biran, A., Liu, W., Li, G., & Eichhorn, V. (2014). Consuming post-disaster destinations: The case of Sichuan, China. Annals of Tourism Research, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakar, K. (2021). Tourophobia: Fear of travel resulting from man-made or natural disasters. Tourism Review, 76(1), 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto de Gante, Á. G., Sosa González, W. E., Bautista Ortega, J., Escobar Castillo, J., & Santillán Fernández, A. (2020). Escala de Likert: Una alternativa para elaborar e interpretar un instrumento de percepción social. Revista de la Alta Tecnología y Sociedad, 12(1), 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo, R., León, C., & Carballo, M. (2022). Gender as moderator of the influence of tourists’ risk perception on destination image and visit intentions. Tourism Review, 77(33), 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M., Solis-Radilla, M. M., Carvache-Franco, W., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2023). the cognitive image and behavioral loyalty of a coastal and marine destination: A study in Acapulco, Mexico. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(2), 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M. A. M. (2022). Factors affecting future travel intentions: Awareness, image, past visitation and risk perception. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(3), 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Analuiza, J. C., Palacios Pérez, J. M., & Plazarte Alomoto, L. V. (2020). Imagen del destino desde la perspectiva del turista (Destination Image from the Tourist’s Perspective). Turismo y Sociedad, 26, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E. Y. T., & Jahari, S. A. (2014). Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tourism Management, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y., & Kim, H. (2021). Risk perception and visit intention on Olympic destination: Symmetric and asymmetric approaches. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(3), 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datatur. (2025). Generación de reportes personalizado de los Centros Turísticos DataTur. Available online: https://monitoreohotelero.sectur.gob.mx/Reportes/Menu.aspx (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Dolnicar, S., & McCabe, S. (2022). Solidarity tourism-How can tourism help the Ukraine and other war-torn countries? Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/4vcpz_v1 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Echeverría, M. (2024, January 20). Acapulco: El lento camino para recuperar el turismo tras el paso de Otis. Expansión. Available online: https://expansion.mx/empresas/2024/01/20/acapulco-lento-camino-recuperar-turismo-paso-otis (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Farfán, L. M., Castillo-Bautista, B. N., & Vázquez-Aguirre, J. L. (2018). Desastres Asociados a Ciclones Tropicales en la Costa Occidental de México: 2011–2015 (J. M. En Rodríguez-Esteves, C. M. Welsh-Rodríguez, M. L. Romo-Aguilar, & A. C. Travieso-Bello, Eds.; pp. 83–104). Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, J., Schuhmann, P., Lake, I., Watkinson, A., & Gill, J. (2012). The influence of hurricane risk on tourist destination choice in the Caribbean. Climatic Change, 114, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics 26 step by step: A simple guide and reference. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de México. (2024). Tianguis Turístico México 2024 en un Acapulco renacido generó más de 35 mil citas de negocios. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/sectur/prensa/tianguis-turistico-mexico-2024-en-un-acapulco-renacido-genero-mas-de-35-mil-citas-de-negocios (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Gorji, A. S., Almeida, F., & Mercadé-Melé, P. (2023). Tourists’ perceived destination image and behavioral intentions towards a sanctioned destination: Comparing visitors and non-visitors. Tourism Management Perspectives, 45, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L., Claret, A., Verbeke, W., Enderli, G., Zakowska-Biemans, S., Vanhonacker, F., Issanchou, S., Sajdakowska, M., Granli, B. S., Scaldevi, L., Contel, M., & Hersleth, M. (2010). Perception of traditional food products in six European regions using free word association. Food Quality and Preference, 21(2), 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, A. B. (2024). The 2023 eastern pacific hurricane season: Otis causes major destruction in acapulco. Weatherwise, 77(4), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M. P., Zanetta, L. D. A., & da Cunha, D. T. (2021). Should I stay, or should I go? Consumers’ perceived risk and intention to visit restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Food Research International, 141, 110152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. K., Ismail, A. R., & Islam, M. F. (2017). Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: A critical review of literature. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1412874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, E. (2025, February 03). Se tiene que fortalecer el turismo del mercado interno. El Sol de Acapulco. Available online: https://oem.com.mx/elsoldeacapulco/local/se-tiene-que-fortalecer-el-turismo-del-mercado-interno-abelina-21038849 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2024). The question of solidarity in tourism. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 16(4), 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M., Wang, K., Liu, Y., & Xu, S. (2024). The impact of post-disaster communication on destination visiting intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(2), 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystad, P. W., & Keller, P. C. (2008). Towards a destination tourism disaster management framework: Long-term lessons from a forest fire disaster. Tourism management, 29(1), 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D., Xu, W., Lee, J., Lee, C., & Woosman, K. M. (2021). Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Assaf, A. G., Woo, L., & Kock, F. (2016). The imagery–image duality model: An integrative review and advocating for improved delimitation of concepts. Journal of Travel Research, 55(6), 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Hede, A. M., Kozak, M., Kock, F., & Assaf, A. (2024). Place solidarity: A case of the Türkiye earthquakes. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 5(1), 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Kock, F., & Assaf, A. G. (2022). In times of war: Place solidarity. Annals of Tourism Research, 96, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Kock, F., Assaf, A. G., & Berbekova, A. (2023). The role of affinity and animosity on solidarity with Ukraine and hospitality outcomes. Tourism Management, 96, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Choi, K. H., & Leopkey, B. (2021). The influence of tourist risk perceptions on travel intention to mega sporting event destinations with different levels of risk. Tourism Economics, 27(3), 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, F., Assaf, A. G., Tsionas, M., Josiassen, A., & Karl, M. (2024). Do tourists stand by the tourism industry? Examining solidarity during and after a pandemic. Journal of Travel Research, 63(3), 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X., Douglas, A. C., & Park, J. (2013). Mediating the effects of natural disasters on travel intention. In Safety and security in Tourism (pp. 29–43). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Zhang, L., Quin, R., & Ryan, C. (2024). Rally-around-the-destination? Changes in host-guest emotional solidarity after crises. Tourism Management, 105, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J., Ritchie, B. W., & Walters, G. (2016). Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoomi, U. M., & Baba, M. M. (2019). Destination image and travel intention of travellers to Jammu & Kashmir: The mediating effect of risk perception. Journal of Hospitality Application & Research, 14(1), 35–56. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/destination-image-travel-intention-travellers/docview/2297130239/se-2 (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Mendoza, E., Silva, R., Enriquez-Ortiz, C., Mariño-Tapia, I., & Felix, A. (2015). Analysis of the hazards and vulnerability of the cancun beach system: The case of hurricane wilma. Extreme Events: Observations, Modeling, and Economics, 214, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N., James, R., & Michael, I. (2018). Australia’s cognitive, affective and conative destination image: An Emirati tourist perspective. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 9(1), 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, C., & Rath, N. (2020). Social solidarity during a pandemic: Through and beyond Durkheimian Lens. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M. E., Kim, D. C., Lehto, X., & Behnke, C. A. (2022). Destination restaurants, place attachment, and future destination patronization. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 28(1), 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2018). Structural equation modeling. In The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 445–456). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal, R., & Polus, R. (2022). Virtual tours as a solidarity tourism product? Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(2), 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. N., & Imamura, F. (2017). Recovering from prolonged negative destination images in post-disaster northern Japan. In Recovering from catastrophic disaster in Asia (pp. 37–59). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B., Dang, H. P., & Nguyen, H. H. (2020). Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1796249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, P. (2023). Acapulco, epicentro del turismo solidario en el Tianguis Turístico 2024. Available online: https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/los-especiales/Acapulco-epicentro-del-turismo-solidario-en-el-Tianguis-Turistico-2024-20231103-0053.html (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Palafox, A., & Gutiérrez, A. G. (2013). Cambio climático y desarrollo turístico. Efectos de los huracanes en Cozumel, Quintana Roo y San Blas, Nayarit. Investigación y Ciencia de la Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, 58, 36–46. Available online: http://192.100.164.85/handle/20.500.12249/2073 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Pascual-Fraile, M. D. P., Talon-Ballestero, P., Villace-Molinero, T., & Ramos-Rodriguez, A. R. (2024). Communication for destinations’ image in crises and disasters: A review and future research agenda. Tourism Review, 79(7), 1385–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]