Emotional Contagion in the Hospitality Industry: Unraveling Its Impacts and Mitigation Strategies Through a Moderated Mediated PLS-SEM Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

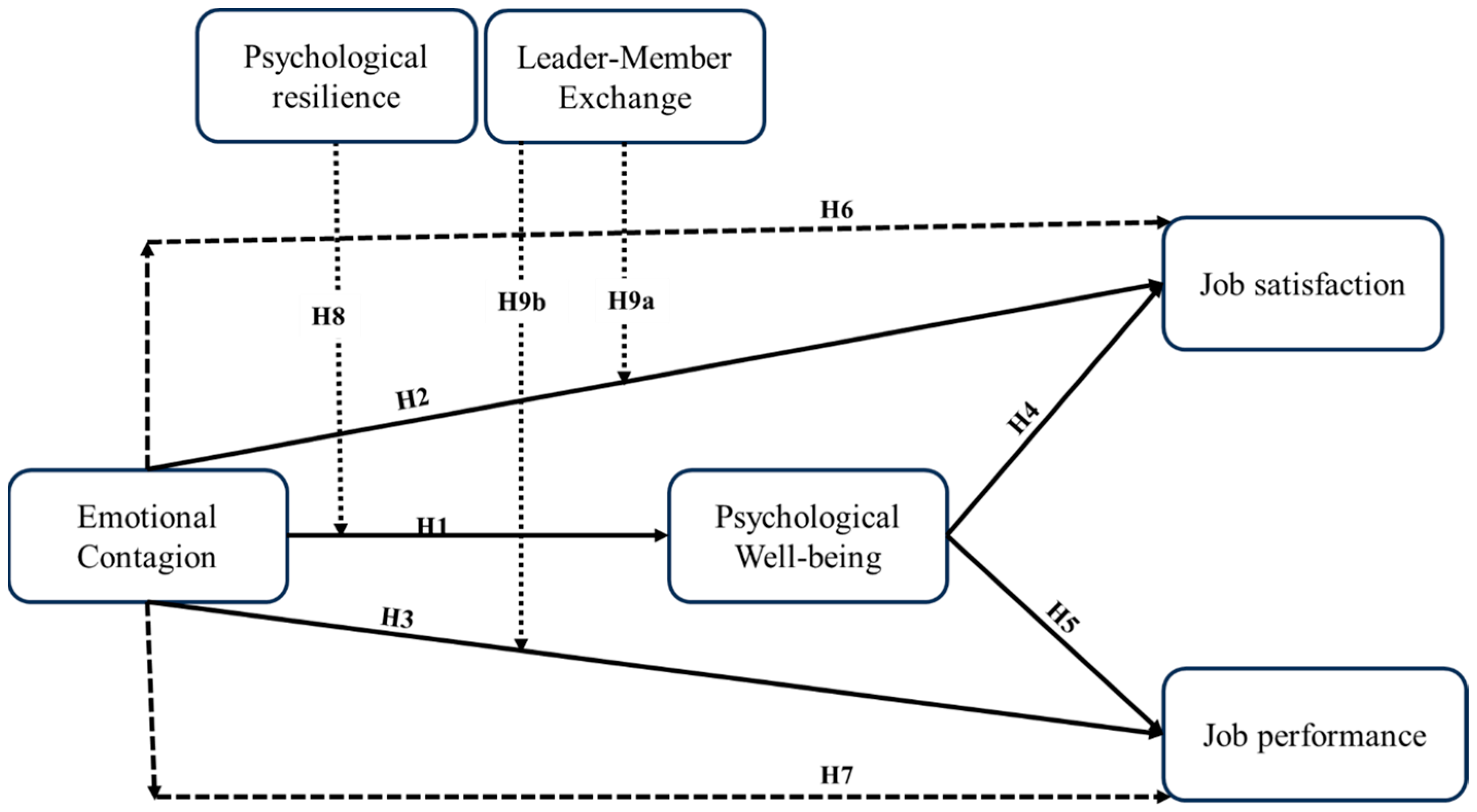

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Emotional Contagion

2.2. Psychological Well-Being

2.3. Job Satisfaction

2.4. Job Performance

2.5. Psychological Resilience

2.6. Leader–Member Exchange (LMX)

2.7. Affective Events Theory (AET) and Emotional Contagion Consequences

2.8. Direct and Mediating Effects of Psychological Well-Being

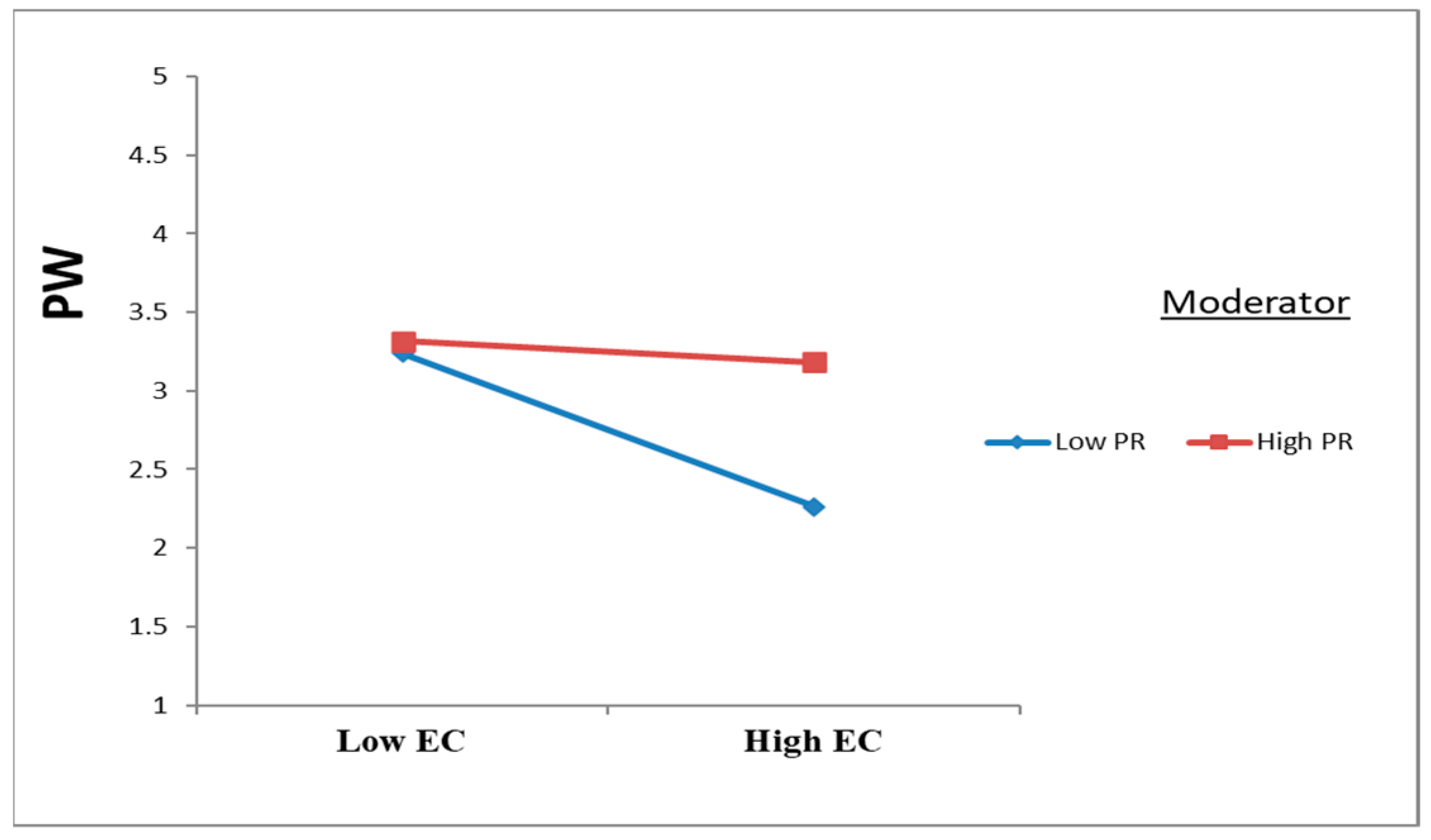

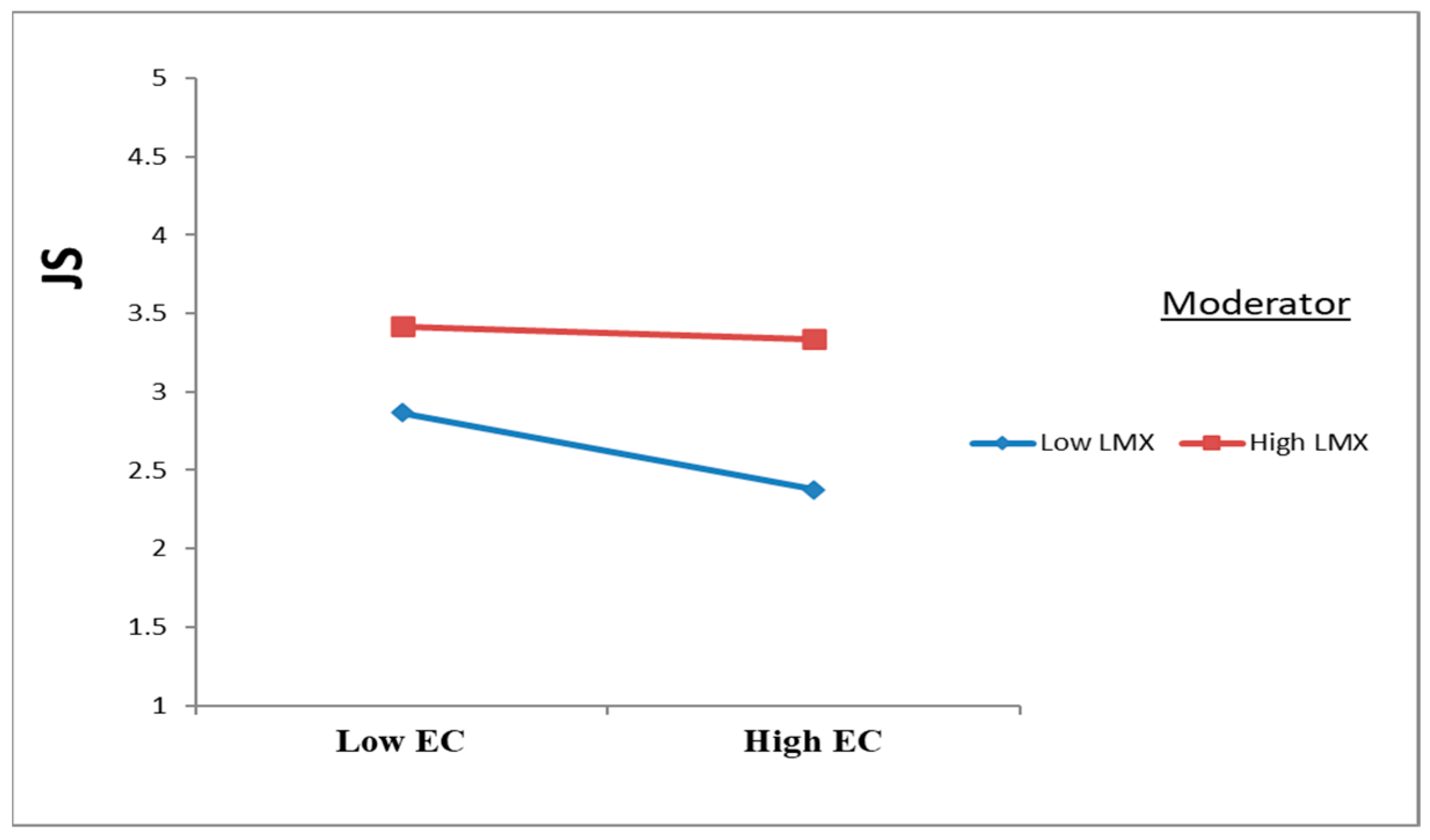

2.9. Moderating Roles of Psychological Resilience and LMX

3. Research Methods

3.1. Instrument and Measures

3.2. Participants and Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Test for Common Method Bias (CMB) and Normality

4.2. Reliability and Construct Validity

4.3. Structural Model and Testing Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings and Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Conclusions

5.4. Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguiar-Quintana, T., Nguyen, T. H. H., Araujo-Cabrera, Y., & Sanabria-Díaz, J. M. (2021). Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyeiwaah, E., Dayour, F., & Zhou, Y. (2022). How does employee commitment impact customers’ attitudinal loyalty? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(2), 350–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy, N. M., & Dorris, A. D. (2017). Emotions in the workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autry, C. W., & Daugherty, P. J. (2003). Warehouse operations employees: Linking person-organization fit, job satisfaction, and coping responses. Journal of Business Logistics, 24(1), 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazz, A. M. S., Elshaer, I. A., Alyahya, M., Abdulaziz, T. A., Elwardany, W. M., & Fayyad, S. (2024). Amplifying unheard voices or fueling conflict? Exploring the impact of leader narcissism and workplace bullying in the tourism industry. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B. J., & Boles, J. S. (1998). Employee behavior in a service environment: A model and test of potential differences between men and women. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P., & Srivastava, M. (2019). A review of emotional contagion: Research propositions. Journal of Management Research, 19(4), 250–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, D. D., Gulati, P., & Pathak, D. V. N. (2021). Effect of job satisfaction on psychological well being and perceived stress among government and private employee. Defence Life Science Journal, 6(4), 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S. G., Coutifaris, C. G. V., & Pillemer, J. (2018). Emotional contagion in organizational life. Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchgrevink, C. P., & Boster, F. J. (1997). Leader-member exchange development: A hospitality antecedent investigation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 16(3), 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, K. C., & Diebig, M. (2021). Following an uneven lead: Trickle-down effects of differentiated transformational leadership. Journal of Management, 47(8), 2105–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J., Williams, J. M., & Griffin, D. (2020). Fostering educational resilience and opportunities in urban schools through equity-focused school–family–community partnerships. Professional School Counseling, 23(1_part_2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V. S., Chambel, M. J., Neto, M., & Lopes, S. (2018). Does work-family conflict mediate the associations of job characteristics with employees’ mental health among men and women? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaika, G. (2020). Psychological characteristics influencing personal autonomy as a factor of psychological well-being. Psychological Journal, 6(1), 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Eyoun, K. (2021). Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuning, A. E., Durham, M. R., Killgore, W. D. S., & Smith, R. (2024). Psychological resilience and hardiness as protective factors in the relationship between depression/anxiety and well-being: Exploratory and confirmatory evidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 225, 112664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalişkan, A., & Köroğlu, E. Ö. (2022). Job performance, task performance, contextual performance: Development and validation of a new scale. Uluslararası İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 8(2), 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devdutt, J., Sudhir, P., & Mehrotra, S. (2023). Development and validation of the workplace affective events survey. Cureus, 15(9), e46236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dim, M. H. (2023). Efficacy of the online skills-based psychological intervention for the enhancement of resilience and mental health well-being among conflict-affected displaced Myanmar people in Thailand: A mixed method study [Master’s thesis, Assumption University of Thailand]. Available online: https://repository.au.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e3c7872d-39c5-477a-9258-5c36e89270b5/content (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Dodanwala, T. C., Santoso, D. S., & Yukongdi, V. (2023). Examining work role stressors, job satisfaction, job stress, and turnover intention of Sri Lanka’s construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management, 23(15), 2583–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Mansour, M. A., & Fayyad, S. (2025a). Perceived greenwashing and employee non-green behavior: The roles of prevention-focused green crafting and work alienation. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2449592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Zain, M. E. A., Fayyad, S., ElShaaer, N. I., & Mahmoud, S. W. (2025b). The dark side of the hospitality industry: Workplace Bullying and employee well-being with feedback avoidance as a mediator and psychological safety as a moderator. Healthcare, 13(3), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A. M., Abdullah Khreis, S. H., Fayyad, S., & Fathy, E. A. (2025). The dynamics of coworker envy in the green innovation landscape: Mediating and moderating effects on employee environmental commitment and non-green behavior in the hospitality industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloria, C. T., & Steinhardt, M. A. (2016). Relationships among positive emotions, coping, resilience and mental health. Stress and Health, 32(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T., Park, J., & Hyun, H. (2020). Customer response toward employees’ emotional labor in service industry settings. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T., & Yi, Y. (2018). The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychology & Marketing, 35(6), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z., Li, C., Jiao, X., & Qu, Q. (2021). Does resilience help in reducing burnout symptoms among chinese students? A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 707792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenidge, D., Devonish, D., & Alleyne, P. (2014). The Relationship between ability-based emotional intelligence and contextual performance and counterproductive work behaviors: A test of the mediating effects of job satisfaction. Human Performance, 27(3), 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., Gong, J., & Huan, T.-C. (2022). Trick or treat! How to reduce co-destruction behavior in tourism workplace based on conservation of resources theory? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.-C., & Lee, J.-W. (2022). Promoting psychological well-being at workplace through protean career attitude: Dual mediating effect of career satisfaction and career commitment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., Agmapisarn, C., & Li, J. (2023). Fear of COVID-19 and employee mental health in quarantine hotels: The role of self-compassion and psychological resilience at work. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 111, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., & Phetvaroon, K. (2022). Beyond the bend: The curvilinear effect of challenge stressors on work attitudes and behaviors. Tourism Management, 90, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. H., Liao, H., Han, J., & Li, A. N. (2021). When leader–member exchange differentiation improves work group functioning: The combined roles of differentiation bases and reward interdependence. Personnel Psychology, 74(1), 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A. A., & Jeong, S. S. (2024). Leader–member exchange (LMX) and work performance: An application of self-determination theory in the work context. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 33(3), 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, U., & Fischer, A. (2017). The role of emotional mimicry in intergroup relations. In Oxford research encyclopedia of communication. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxha, G., Simeli, I., Theocharis, D., Vasileiou, A., & Tsekouropoulos, G. (2024). sustainable healthcare quality and job satisfaction through organizational culture: Approaches and outcomes. Sustainability, 16(9), 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N., Qiu, S., Yang, S., & Deng, R. (2021). Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Mediation of trust and psychological well-being. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A., & Dyaram, L. (2020). Perceived diversity and employee well-being: Mediating role of inclusion. Personnel Review, 49(5), 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. R., & Park, S. (2020). Mindfulness training for tourism and hospitality frontline employees. Industrial and Commercial Training, 52(4), 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2019). Emotional contagion and collective commitment among leaders and team members in deluxe hotel. Service Business, 13(4), 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N. Y., & Seock, Y.-K. (2017). Effect of service recovery on customers’ perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliath, P., Kalliath, T., & Chan, C. (2017). Work–family conflict, family satisfaction and employee well-being: A comparative study of Australian and Indian social workers. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(3), 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O. M., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Hassannia, R. (2021). Sense of calling, emotional exhaustion and their effects on hotel employees’ green and non-green work outcomes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(10), 3705–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O. M., Uludag, O., Menevis, I., Hadzimehmedagic, L., & Baddar, L. (2006). The effects of selected individual characteristics on frontline employee performance and job satisfaction. Tourism Management, 27(4), 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. L., Waters, L., Adler, A., & White, M. (2014). Assessing employee wellbeing in schools using a multifaceted approach: Associations with physical health, life satisfaction, and professional thriving. Psychology, 5(6), 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersemaekers, W., Rupprecht, S., Wittmann, M., Tamdjidi, C., Falke, P., Donders, R., Speckens, A., & Kohls, N. (2018). A workplace mindfulness intervention may be associated with improved psychological well-being and productivity. A preliminary field study in a company setting. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khtatbeh, M. M., Mahomed, A. S. B., Rahman, S. bin A., & Mohamed, R. (2020). The mediating role of procedural justice on the relationship between job analysis and employee performance in Jordan Industrial Estates. Heliyon, 6(10), e04973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidger, J., Brockman, R., Tilling, K., Campbell, R., Ford, T., Araya, R., King, M., & Gunnell, D. (2016). Teachers’ wellbeing and depressive symptoms, and associated risk factors: A large cross sectional study in English secondary schools. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore, W. D. S., Taylor, E. C., Cloonan, S. A., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Chun, J., Kim, J., Ju, H.-J., Kim, B. J., Jeong, J., & Lee, D. H. (2024). Emotion regulation from a virtue perspective. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laybourn, S., Frenzel, A. C., Constant, M., & Liesefeld, H. R. (2022). Unintended emotions in the laboratory: Emotions incidentally induced by a standard visual working memory task relate to task performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(7), 1591–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A., Thomas, G., Martin, R., & Guillaume, Y. (2019). Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) ambivalence and task performance: The cross-domain buffering role of social support. Journal of Management, 45(5), 1927–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Li, C., & Wang, Z. (2021). An agent-based model for exploring the impacts of reciprocal trust on knowledge transfer within an organization. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 36(8), 1486–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., Liu, Y., Park, Y., & Wang, L. (2022). Treat me better, but is it really better? Applying a resource perspective to understanding leader–member exchange (LMX), LMX differentiation, and work stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(2), 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z., Liu, W., Li, X., & Song, Z. (2019). Give and take: An episodic perspective on leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(1), 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y., Chi, N.-W., & Gremler, D. D. (2019). Emotion cycles in services: Emotional contagion and emotional labor effects. Journal of Service Research, 22(3), 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D., & Hong, D. (2022). Emotional contagion: Research on the Influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 931835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, H. P. (2020). Emotion regulation, positive affect, and promotive voice behavior at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marieta, D. P., Maryam, W., & R, B. J. (2020). The role of emotional intelligence and autonomy in transformational leadership: A leader member exchange perspective. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascareño, J., Rietzschel, E., & Wisse, B. (2020). Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) and innovation: A test of competing hypotheses. Creativity and Innovation Management, 29(3), 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca, S., Kafetsios, K., Livi, S., & Presaghi, F. (2019). Emotion regulation and satisfaction in long-term marital relationships: The role of emotional contagion. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(9), 2880–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A., & Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy. Journal of Personality, 40(4), 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, H., & Lone, Z. A. (2022). Incorporating psychological well-being as a policy in multifaceted corporate culture. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 9392–9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, U., & Sreeja, T. (2018). Impact of leader emotional displays and emotional contagion at work in India: An in class experiential activity. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 67, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, M. J., Hughes, M., & Ramos, H. M. (2023). Middle-managers’ innovative behavior: The roles of psychological empowerment and personal initiative. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(18), 3464–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, E. (2016). Employee voluntary turnover as a negative indicator of organizational effectiveness. Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management, 4(2), 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oggiano, M. (2022). Neurophysiology of emotions. In Neurophysiology—Networks, plasticity, pathophysiology and behavior. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L., & Naughton, S. (2015). Mapping the association of emotional contagion to leaders, colleagues, and clients: Implications for leadership. Organization Management Journal, 12(3), 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L., Probst, T. M., Ghezzi, V., & Barbaranelli, C. (2019). Cognitive failures in response to emotional contagion: Their effects on workplace accidents. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 125, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L., Probst, T. M., Ghezzi, V., & Barbaranelli, C. (2021). Emotional contagion as a trigger for moral disengagement: Their effects on workplace injuries. Safety Science, 140, 105317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, R. K., & Hati, L. (2022). The measurement of employee well-being: Development and validation of a scale. Global Business Review, 23(2), 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazkova, E., & Kret, M. E. (2017). Connecting minds and sharing emotions through mimicry: A neurocognitive model of emotional contagion. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quratulain, S. (2020). Trust Violation and recovery dynamics in the context of differential supervisor-subordinate relationships: A study of public service employees. Public Integrity, 22(2), 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reh, S., Wieck, C., & Scheibe, S. (2021). Experience, vulnerability, or overload? Emotional job demands as moderator in trajectories of emotional well-being and job satisfaction across the working lifespan. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(11), 1734–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizer, A., Brender-Ilan, Y., & Sheaffer, Z. (2019). Employee motivation, emotions, and performance: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(6), 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouxel, G., Michinov, E., & Dodeler, V. (2016). The influence of work characteristics, emotional display rules and affectivity on burnout and job satisfaction: A survey among geriatric care workers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 62, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, S., Ingoglia, S., Bonfanti, R. C., & Lo Coco, G. (2021). The role of online social comparison as a protective factor for psychological wellbeing: A longitudinal study during the COVID-19 quarantine. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2023). Self-determination theory: Metatheory, methods, and meaning. In The Oxford handbook of self-determination theory (pp. 3–30). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansinenea, E., Asla, N., Agirrezabal, A., Fuster-Ruiz-de-Apodaca, M. J., Muela, A., & Garaigordobil, M. (2020). Being yourself and mental health: Goal motives, positive affect and self-acceptance protect people with HIV from depressive symptoms. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(2), 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simillidou, A., Christofi, M., Glyptis, L., Papatheodorou, A., & Vrontis, D. (2020). Engaging in emotional labour when facing customer mistreatment in hospitality. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S., Yang, X., Yang, H., Zhou, P., Ma, H., Teng, C., Chen, H., Ou, H., Li, J., Mathews, C. A., Nutley, S., Liu, N., Zhang, X., & Zhang, N. (2021). Psychological Resilience as a protective factor for depression and anxiety among the public during the outbreak of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 618509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, P. E. (2022). Well-being and evolving work autonomy: The locus of control construct revisited. American Journal of Health Promotion, 36(4), 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M., Carsten, M., Huang, L., & Maslyn, J. (2022). What do managers value in the leader-member exchange (LMX) relationship? Identification and measurement of the manager’s perspective of LMX (MLMX). Journal of Business Research, 148, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USLU, Ö. (2022). The relationship between attitudes towards school and general self-efficacy: The moderation effect of level of education. In Current researches in educational sciences V. Akademisyen Publishing House Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ustrov, Y., Valverde, M., & Ryan, G. (2016). Insights into emotional contagion and its effects at the hotel front desk. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(10), 2285–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde Pierce, S., Haro, A. Y., Ayón, C., & Enriquez, L. E. (2021). Evaluating the 0ts. Journal of Latinos and Education, 20(3), 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.-L., & Pai, N. (2019). A theoretical review of psychological resilience: Defining resilience and resilience research over the decades. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 7(2), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J., Sinha, A., Bhattacharjee, S. B., & Tuan Luu, T. (2024). Emotional intelligence as an antecedent of employees’ job outcomes through knowledge sharing in IT-ITeS firms. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzeletti, C., Zammuner, V. L., Galli, C., & Agnoli, S. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial well-being in adolescence. Cogent Psychology, 3(1), 1199294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, N. Q., Hien, L. M., & Do, Q. H. (2022). The relationship between transformation leadership, job satisfaction and employee motivation in the tourism industry. Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Zhang, S., & Fan, Y. (2024). Relationship between daily job resources and job performance: The mediating role of emotions from within-perspective. Sage Open, 14(4), 21582440241293549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Shaheryar. (2020). Work-Related Flow: The development of a theoretical framework based on the high involvement HRM practices with mediating role of affective commitment and moderating effect of emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 564444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrt, W., Casper, A., & Sonnentag, S. (2022). More than a muscle: How self-control motivation, depletion, and self-regulation strategies impact task performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(8), 1358–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Elsevier Science/JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. E., Thomas, J. S., Bennett, A. A., Banks, G. C., Toth, A., Dunn, A. M., McBride, A., & Gooty, J. (2024). The role of discrete emotions in job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(1), 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. M., Weiss, A., & Shook, N. J. (2020). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and savoring: Factors that explain the relation between perceived social support and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M. J., Cozens, R., & Brunetto, Y. (2023). Catching emotions: The moderating role of emotional contagion between leader-member exchange, psychological capital and employee well-being. Personnel Review, 52(7), 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablah, A. R., Sirianni, N. J., Korschun, D., Gremler, D. D., & Beatty, S. E. (2017). Emotional convergence in service relationships: The Shared frontline experience of customers and employees. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. (2018). A review of researches workplace loneliness. Psychology, 9(5), 1005–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Zhang, W., & Li, C. (2023). Modeling emotional contagion in the COVID-19 pandemic: A complex network approach. PeerJ Computer Science, 9, e1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Group (N = 792) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 567 | 72.6 | |

| Female | 214 | 27.4 | |

| Age group | |||

| 18–29 | 336 | 43.0 | |

| 30–39 | 233 | 29.8 | |

| 40–49 | 173 | 22.2 | |

| 50–59 | 38 | 4.9 | |

| 60 and above | 1 | .1 | |

| Education | |||

| High School | 42 | 5.4 | |

| Middle school | 390 | 49.9 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 267 | 34.2 | |

| Postgraduate | 28 | 3.6 | |

| Other | 54 | 6.9 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 446 | 57.1 | |

| Single | 320 | 41.0 | |

| Divorced | 15 | 1.9 | |

| Experience | |||

| Less than 2 years | 156 | 20.0 | |

| 2 to 5 years | 176 | 22.5 | |

| 5 to 10 years | 136 | 17.4 | |

| More than 10 years | 313 | 40.1 |

| Factors and Items | Λ | VIF | Mean | SD | SK | KU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional contagion (EC) (α = 0.868, CR = 0.899, AVE = 0.597) | ||||||

| EC1 | 0.802 | 2.045 | 3.042 | 1.360 | −0.267 | −1.253 |

| EC2 | 0.788 | 1.743 | 2.303 | 1.125 | 0.586 | −0.624 |

| EC3 | 0.768 | 3.326 | 3.169 | 1.390 | −0.422 | −1.175 |

| EC4 | 0.766 | 3.375 | 3.177 | 1.388 | −0.483 | −1.142 |

| EC5 | 0.750 | 1.685 | 2.378 | 1.196 | 0.534 | −0.747 |

| EC6 | 0.762 | 1.828 | 2.955 | 1.269 | −0.195 | −1.055 |

| Psychological well-being (PW) (α = 0.960, CR = 0.965, AVE = 0.734) | ||||||

| PW1 | 0.839 | 4.403 | 4.129 | 0.897 | −1.356 | 2.347 |

| PW2 | 0.852 | 4.689 | 4.136 | 0.893 | −1.375 | 2.400 |

| PW3 | 0.852 | 3.053 | 4.078 | 0.966 | −1.413 | 2.176 |

| PW4 | 0.860 | 4.552 | 4.164 | 0.909 | −1.416 | 2.385 |

| PW5 | 0.871 | 4.878 | 4.177 | 0.878 | −1.387 | 2.481 |

| PW6 | 0.860 | 4.406 | 4.136 | 0.938 | −1.508 | 2.722 |

| PW7 | 0.862 | 4.489 | 4.138 | 0.940 | −1.449 | 2.416 |

| PW8 | 0.873 | 4.378 | 4.311 | 0.910 | −1.791 | 3.647 |

| PW9 | 0.845 | 3.702 | 4.383 | 0.989 | −2.078 | 4.227 |

| PW10 | 0.854 | 3.789 | 4.355 | 0.937 | −1.885 | 3.703 |

| Job satisfaction (JS) (α = 0.920, CR = 0.944, AVE = 0.807) | ||||||

| JS1 | 0.924 | 3.619 | 4.074 | 0.932 | −1.396 | 2.405 |

| JS2 | 0.900 | 3.240 | 3.928 | 0.996 | −1.089 | 1.095 |

| JS3 | 0.873 | 2.641 | 3.772 | 1.037 | −0.901 | 0.548 |

| JS4 | 0.894 | 2.970 | 3.877 | 1.033 | −1.075 | 1.010 |

| Job performance (JP) (α = 0.935, CR = 0.951, AVE = 0.794) | ||||||

| JP1 | 0.918 | 4.713 | 4.061 | 1.071 | −1.497 | 1.998 |

| JP2 | 0.914 | 4.717 | 3.930 | 1.105 | −1.174 | 0.938 |

| JP3 | 0.847 | 2.710 | 3.784 | 1.166 | −0.867 | 0.053 |

| JP4 | 0.914 | 3.943 | 4.175 | 1.076 | −1.722 | 2.632 |

| JP5 | 0.860 | 2.623 | 4.161 | 1.049 | −1.684 | 2.658 |

| Leader–member exchange (LMX) (α = 0.933, CR = 0.949, AVE = 0.790) | ||||||

| LMX1 | 0.919 | 4.566 | 3.835 | 1.288 | −1.195 | 0.345 |

| LMX2 | 0.917 | 4.412 | 3.667 | 1.254 | −0.946 | −0.073 |

| LMX3 | 0.884 | 2.997 | 3.309 | 1.206 | −0.526 | −0.586 |

| LMX4 | 0.916 | 3.876 | 3.608 | 1.241 | −0.894 | −0.135 |

| LMX5 | 0.803 | 2.191 | 3.157 | 1.256 | −0.299 | −0.972 |

| Psychological resilience (PR) (α = 0.959, CR = 0.965, AVE = 0.732) | ||||||

| PR1 | 0.879 | 3.770 | 3.971 | 0.907 | −1.387 | 2.461 |

| PR2 | 0.888 | 4.561 | 3.848 | 0.930 | −1.044 | 1.372 |

| PR3 | 0.800 | 2.779 | 3.688 | 0.942 | −0.671 | 0.580 |

| PR4 | 0.790 | 2.461 | 3.750 | 0.995 | −0.791 | 0.477 |

| PR5 | 0.852 | 3.152 | 3.914 | 0.991 | −1.065 | 1.118 |

| PR6 | 0.884 | 4.076 | 4.083 | 0.908 | −1.307 | 1.998 |

| PR7 | 0.883 | 3.997 | 3.982 | 0.950 | −1.251 | 1.761 |

| PR8 | 0.891 | 4.576 | 4.072 | 0.911 | −1.293 | 1.973 |

| PR9 | 0.891 | 4.214 | 4.155 | 0.934 | −1.420 | 2.197 |

| PR10 | 0.788 | 2.319 | 3.903 | 0.953 | −1.025 | 1.101 |

| Constructs | EC | JP | JS | LMX | PR | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional contagion (EC) | 0.773 | |||||

| Job performance (JP) | −0.289 | 0.891 | ||||

| Job satisfaction (JS) | −0.235 | 0.468 | 0.898 | |||

| Leader–member exchange (LMX) | 0.214 | 0.364 | 0.411 | 0.889 | ||

| Psychological resilience (PR) | −0.167 | 0.441 | 0.438 | 0.313 | 0.856 | |

| Psychological well-being (PW) | −0.327 | 0.635 | 0.581 | 0.270 | 0.404 | 0.857 |

| Constructs | EC | JP | JS | LMX | PR | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional contagion (EC) | ||||||

| Job performance (JP) | 0.304 | |||||

| Job satisfaction (JS) | 0.255 | 0.498 | ||||

| Leader–member exchange (LMX) | 0.259 | 0.385 | 0.438 | |||

| Psychological resilience (PR) | 0.177 | 0.461 | 0.462 | 0.329 | ||

| Psychological well-being (PW) | 0.343 | 0.665 | 0.614 | 0.282 | 0.419 |

| Hypothesis | β | t | p | F2 | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||||

| H1: EC → PW | −0.278 | 8.138 | 0.000 | 0.104 | ✔ |

| H2: EC → JS | −0.143 | 4.351 | 0.000 | 0.028 | ✔ |

| H3: EC → JP | −0.141 | 4.168 | 0.000 | 0.033 | ✔ |

| H4: PW → JS | 0.380 | 7.105 | 0.000 | 0.165 | ✔ |

| H5: PW → JP | 0.372 | 6.487 | 0.000 | 0.188 | ✔ |

| Indirect mediating effect | |||||

| H6: EC → PW → JS | −0.106 | 5.639 | 0.000 | ✔ | |

| H7: EC → PW → JP | −0.104 | 5.648 | 0.000 | ✔ | |

| Moderating effects | |||||

| H8: EC × PR → PW | 0.212 | 5.543 | 0.000 | ✔ | |

| H9a: EC × LMX → JS | 0.102 | 3.119 | 0.002 | ✔ | |

| H9b: EC × LMX → JP | 0.222 | 6.477 | 0.000 | ✔ | |

| Job performance | R2 | 0.532 | Q2 | 0.391 | |

| Job satisfaction | R2 | 0.442 | Q2 | 0.332 | |

| Psychological well-being | R2 | 0.278 | Q2 | 0.190 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Alyahya, M.; Mohammad, A.A.A.; Fayyad, S.; Elsawy, O. Emotional Contagion in the Hospitality Industry: Unraveling Its Impacts and Mitigation Strategies Through a Moderated Mediated PLS-SEM Approach. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010046

Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, Alyahya M, Mohammad AAA, Fayyad S, Elsawy O. Emotional Contagion in the Hospitality Industry: Unraveling Its Impacts and Mitigation Strategies Through a Moderated Mediated PLS-SEM Approach. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Alaa M. S. Azazz, Mansour Alyahya, Abuelkassem A. A. Mohammad, Sameh Fayyad, and Osman Elsawy. 2025. "Emotional Contagion in the Hospitality Industry: Unraveling Its Impacts and Mitigation Strategies Through a Moderated Mediated PLS-SEM Approach" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010046

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Alyahya, M., Mohammad, A. A. A., Fayyad, S., & Elsawy, O. (2025). Emotional Contagion in the Hospitality Industry: Unraveling Its Impacts and Mitigation Strategies Through a Moderated Mediated PLS-SEM Approach. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010046