The Place and Role of Environmental Labels for Tourist Accommodations: A Survey-Based Characterisation for the European Union

Abstract

1. Introduction

Focus on Tourist Accommodation

2. Materials and Methods

- Section 1 gathered general information on the label/scheme and its basic characteristics.

- Section 2 focused on the scope of the label/scheme, with questions ranging from service coverage to geographical scope.

- Section 3 aimed to collect information on the certification procedure, in terms of the type of label/scheme, criteria considered, or the audit procedure type and compliance with any ISO standards.

- Section 4 aimed to collate information on the certified tourist accommodation services, i.e., the number of tourism services possessing a label/scheme and their geographical location.

- Finally, Section 5 collected the entities’ contact details.

3. Results

- Geographical scope, i.e., prioritising the worldwide, European-wide, or multiple European country ones over those covering single countries or regions.

- Language, i.e., selecting those with an English website to facilitate ease of comprehension.

- Prioritisation given to labels cited in at least four different literature sources (see Appendix A for a complete overview of the sources consulted).

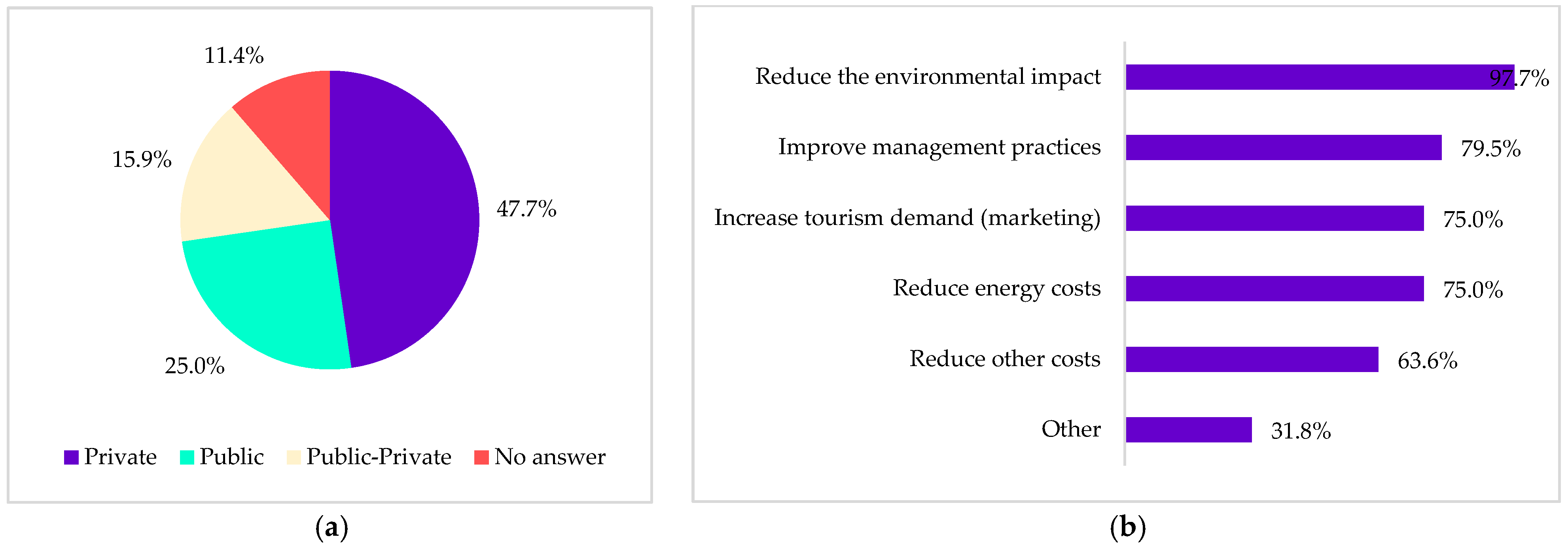

3.1. General Information

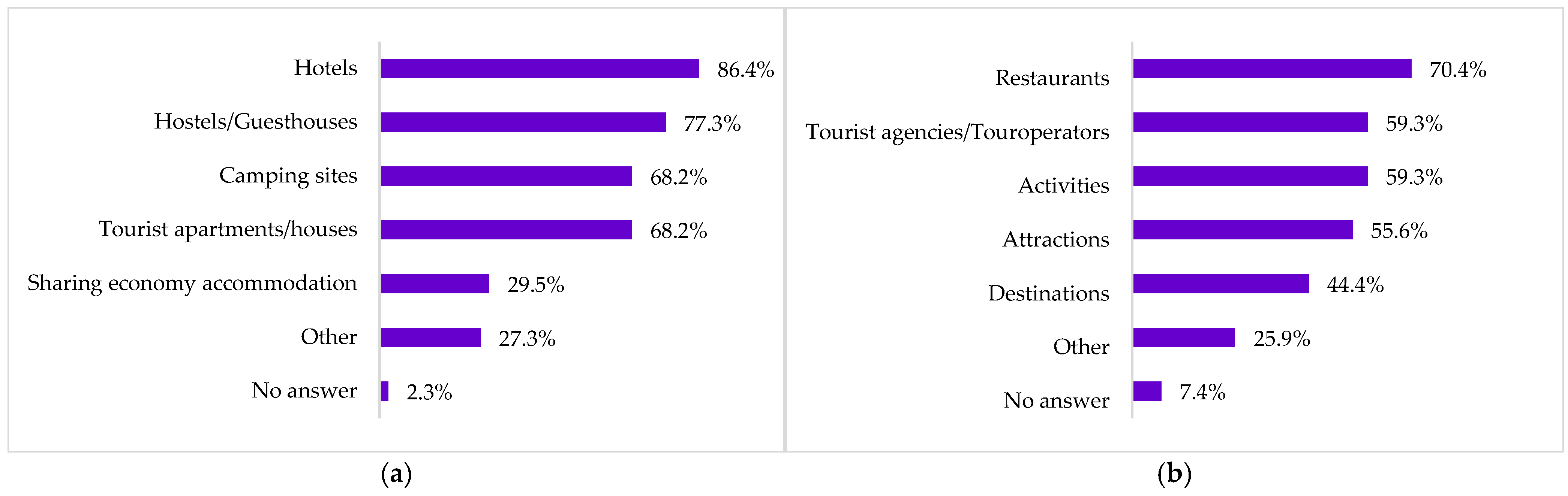

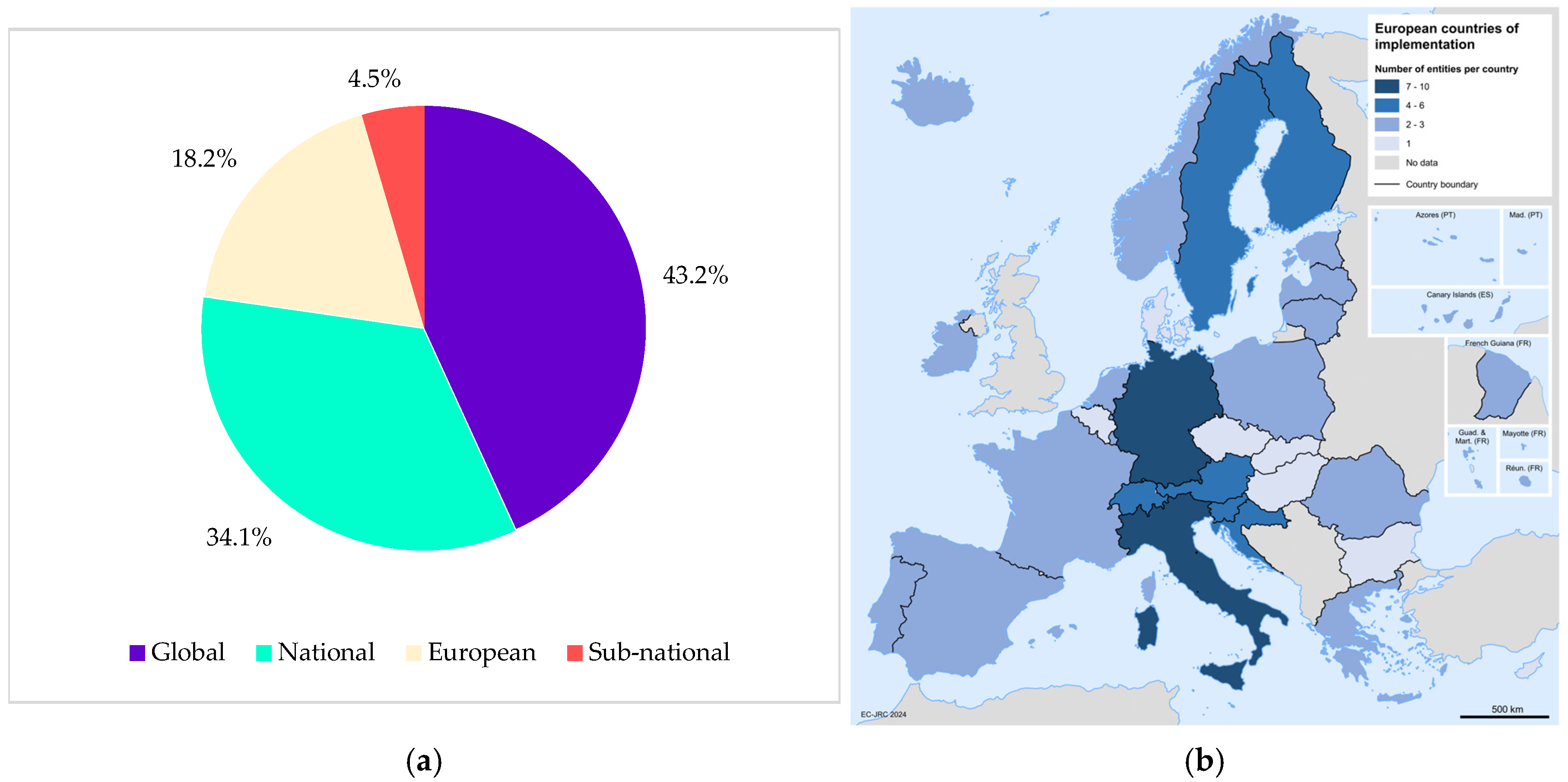

3.2. Geographical and Sectoral Scope of Ecolabels

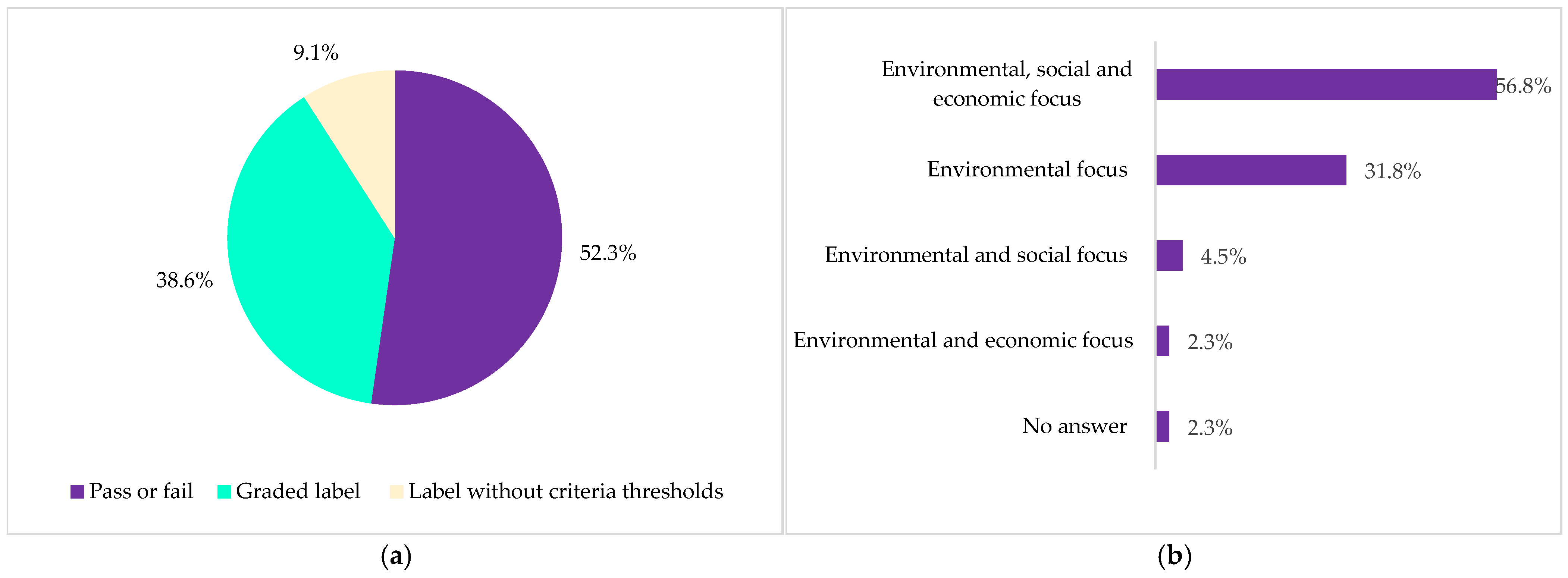

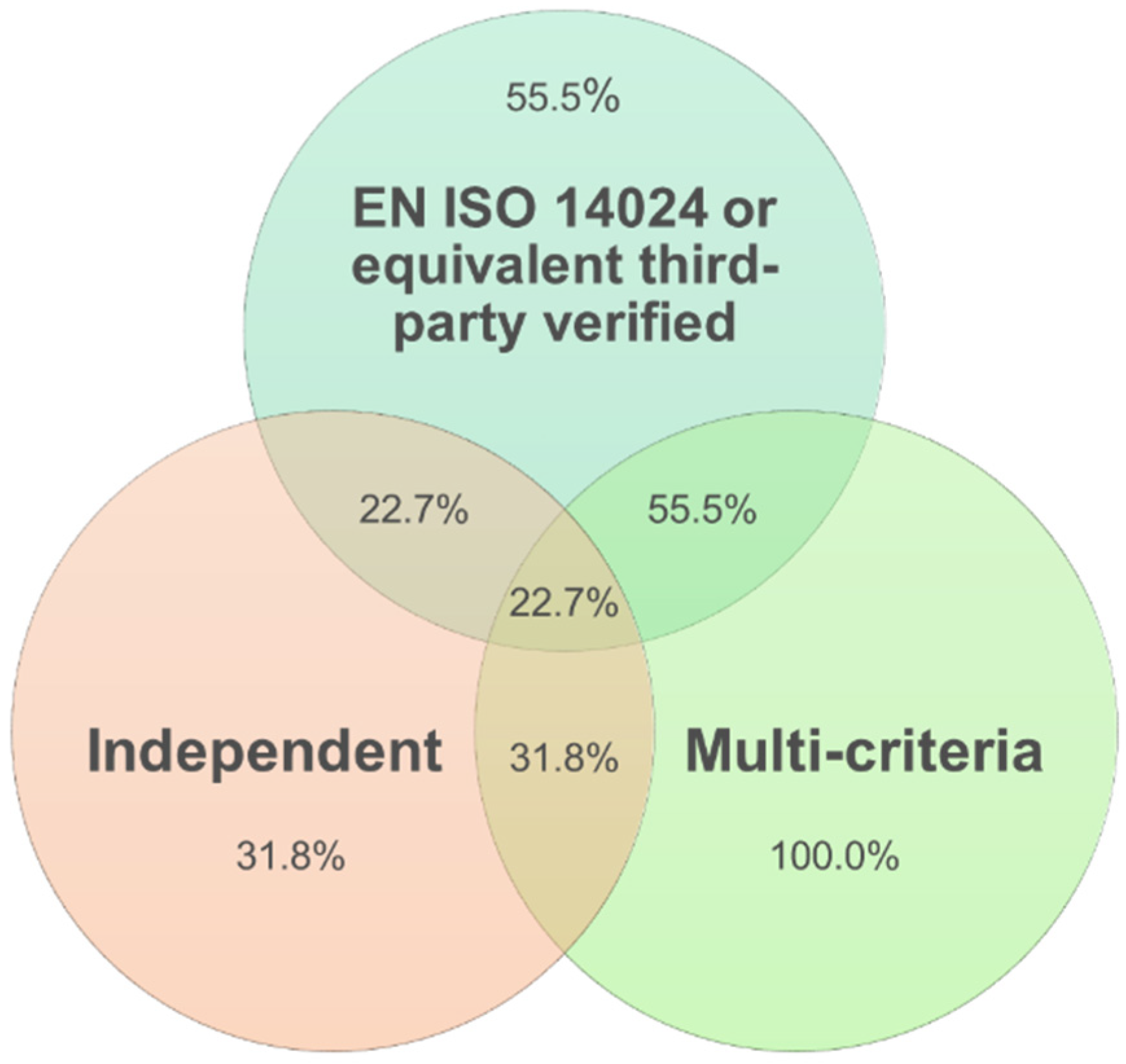

3.3. Certification Procedure

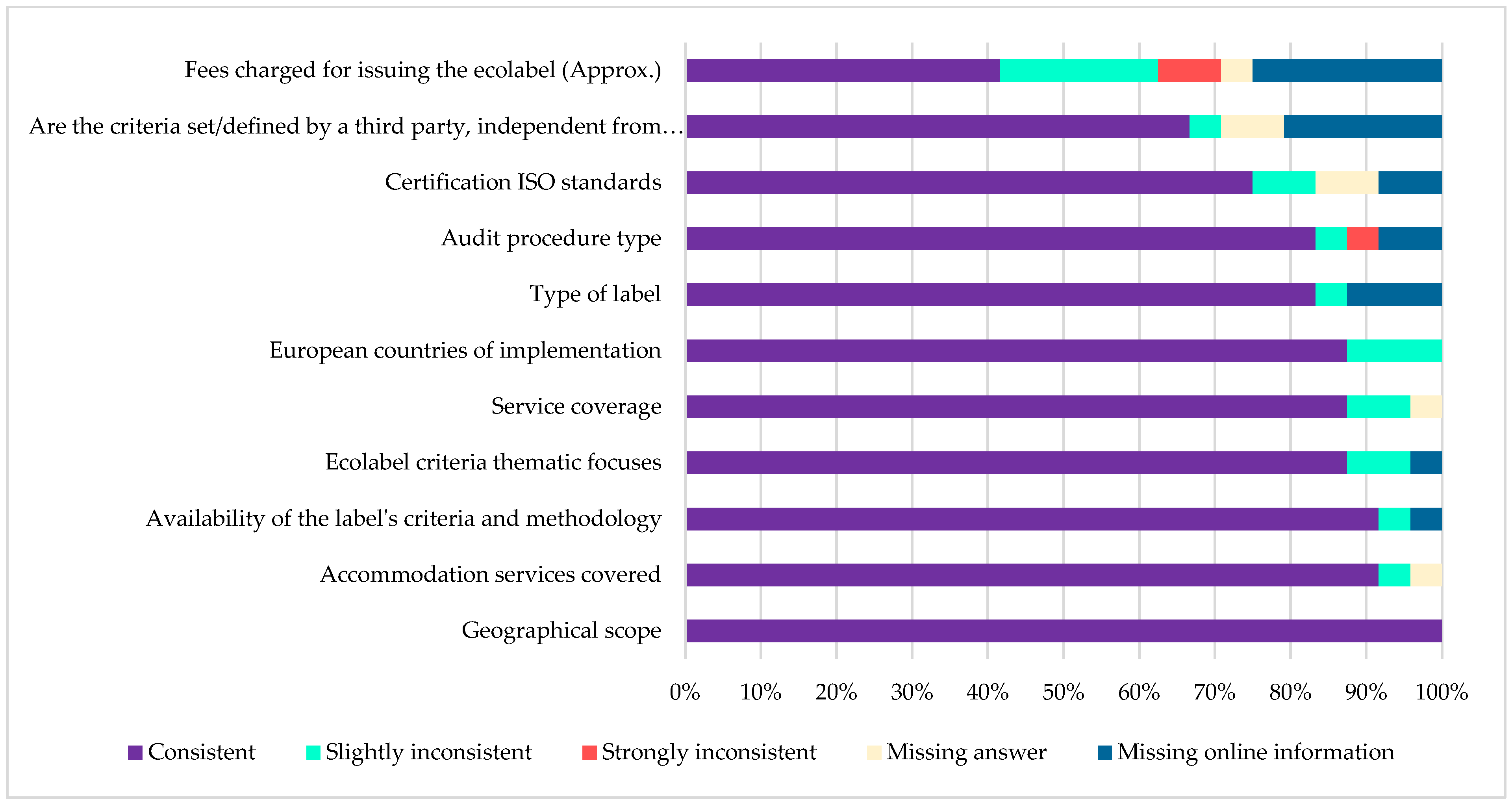

3.4. Quality Check

- “Consistent”; survey reply corresponds to what is shown online.

- “Slightly inconsistent”; survey reply slightly differs from that which is shown online but does not compromise the main conclusions. For example, some details are missing or do not match entirely.

- “Strongly inconsistent”; survey reply is completely different from that which is shown online.

- “Missing answer”; the entity did not provide any reply to that specific question independently from what is shown online.

- “Missing online information”; the entity did provide a reply in the survey, but it was not possible to verify the reply because the information was not available online.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Ecolabel | Citations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Shortlisted for the Characterisation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sustainable Holiday Residence—Nachhaltige Ferienimmobilie | 15 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 2 | Green Globe | 13 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| 3 | Earth Check Certification | 12 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| 4 | EU Ecolabel | 10 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| 5 | Travelife | 10 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| 6 | TourCert | 9 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 7 | Austrian Ecolabel for Tourism | 8 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| 8 | Biosphere | 8 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| 9 | Blue Flag | 8 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 10 | EcoCertification Malta | 8 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 11 | Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) | 7 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 12 | Green Tourism Business Scheme (GTBS) | 7 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| 13 | ibex fairstay | 7 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 14 | Nordic Swan Ecolabelling | 7 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 15 | Biohotels * | 6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| 16 | Green Seal | 6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| 17 | EcoLabel Luxembourg | 5 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 18 | Green Sign | 5 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| 19 | Viabono * | 5 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 20 | EMAS | 4 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 21 | European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas EUROPARC | 4 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 22 | Green Destinations (GD) Standard | 4 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 23 | Green Key * | 4 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 24 | Legambiente Turismo * | 4 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 25 | Preferred by Nature Sustainable Tourism Standard for Accommodation | 4 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 26 | Certified Green Hotel | 3 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 27 | Eco-Romania | 3 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 28 | Estonian Ecotourism Quality Label (EHE) | 3 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 29 | GREAT Green Deal | 3 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 30 | Sustainable Hostelling (HI-Q & S) | 3 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 31 | ISO 14001 | 3 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 32 | Sustainable Travel Ireland | 3 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 33 | Actively Green Standard | 2 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 34 | Alpine Pearls * | 2 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 35 | Audubon Green Hospitality Program | 2 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 36 | Blaue Schwalbe | 2 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 37 | ECOCAMPING | 2 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 38 | Green Certificate: Latvia | 2 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 39 | Green Growth 2050 | 2 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 40 | LEED | 2 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 41 | Nature’s Best Ecotourism | 2 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 42 | Slovenia Green | 2 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 43 | Biosphärengastgeber | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 44 | BREEAM | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 45 | Club de Producto Turístico Reservas de Biosfera Españolas | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 46 | Dalmatia Green | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 47 | David Bellamy Conservation Award | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 48 | DEHOGA Bundersverband * | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 49 | Eco hotels certified | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 50 | Eco-Lighthouse * | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 51 | Ecotourism Norway | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 52 | EMAS easy | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 53 | European Destination of Excellence (EDEN) | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 54 | European Ecotourism Labelling Standard (EETLS) | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 55 | European Green Capital | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 56 | European Leaf Award | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 57 | European Smart Tourism Capital | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 58 | European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS) | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 59 | Geo Certified | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 60 | Global Destination Sustainability Index (GDS-I) | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 61 | Global Ecosphere Retreats GER Standard | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 62 | Good Travel Seal | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 63 | Green Hospitality Award | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 64 | Green Pearls Unique Places * | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 65 | Green Tourism Active Standard | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 66 | GreenStep Sustainable Tourism Standard | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 67 | Hilton LightStay | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 68 | Hungarian Ecolabel/Környezetbarát Termék Védjegy | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 69 | Innovation Norway’s Sustainable Destination Scheme | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 70 | ISO 50001 | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 71 | Klimaneutral | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 72 | One Planet Living | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 73 | Partner der Nationalen | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 74 | staygreencheck | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 75 | Sustainable Holiday Residence—Nachhaltige Ferienimmobilie | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 76 | Sustainable Travel Finland | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 77 | Terres de l’Ebre Brand | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 78 | The International Ecotourism society | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 79 | Tripadvisor Green Leaders * | 1 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 80 | Umweltgütesiegel auf Alpenvereinshütten | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 81 | WTTC Tourism for Tomorrow Awards | 1 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 82 | Earth Check Design | 0 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 83 | EcoChi 180º | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 84 | Green tourism and green meetings | 0 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 86 | Ekokompassi (EcoCompass) | 0 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 85 | EMA Green Seal for hospitality | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 86 | Global Ecosphere Retreats Standard | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 87 | Green Leaf Foundation | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 88 | Klimafreundlicher Betrieb | 0 | x | |||||||||||||||

| 89 | Sustainable Hospitality Alliance | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 90 | UN Certification for Sustainable Tourism | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

Appendix B

| 1. General information | * Name of the ecolabel | |

| * Issuer entity name | ||

| * Issuer entity owner | ||

| Is the owner a public or private entity? | Public | |

| Private | ||

| Public-private | ||

| Ecolabel website (URL) | ||

| Issuer entity address | ||

| Date of establishment | ||

| General description | ||

| What are the potential motivators to obtain the label? | Reduce the environmental impact | |

| Increase tourism demand (marketing) | ||

| Reduce energy costs | ||

| Reduce other costs | ||

| Improve management practices | ||

| Other | ||

| 2. Scope of the ecolabel | Service coverage | Accommodation |

| Accomodation and other tourism services | ||

| Accommodation services covered | Hotels | |

| Hotels/guesthouses | ||

| Tourist apartments/houses | ||

| Campings | ||

| Sharing economy accommodation | ||

| Other | ||

| * Geographical scope | Global | |

| European | ||

| National | ||

| Sub-national | ||

| Country of implementation (Europe) | ||

| 3. Certification procedure | * Type of label | Pass or fail (all criteria must be fulfilled or a minimum score has to be reached according to a scoring system) |

| Graded label (different grades of criterial fulfillment are foreseen— e.g., bronze, silver, gold) | ||

| Label without criteria thresholds (management label or open choice on which criteria fulfill) | ||

| * Ecolabel criteria thematic focuses | Environmental focus | |

| Economic focus | ||

| Social focus | ||

| Other | ||

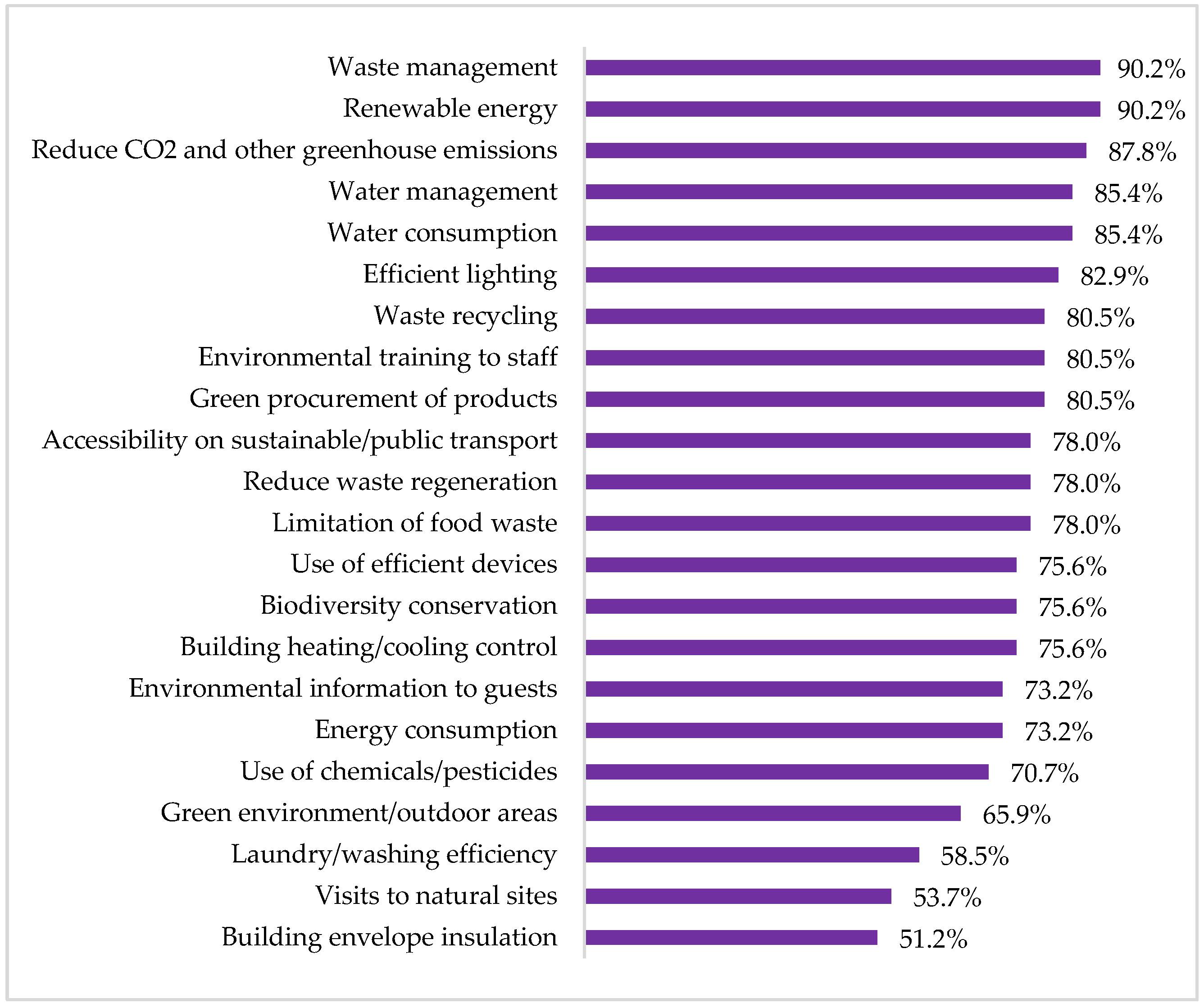

| Evaluation criteria related to the environment | Water consumption | |

| Water management | ||

| Laundry/washing efficiency | ||

| Waste recycling | ||

| Waste management | ||

| Reduce waste generation | ||

| Energy consumption | ||

| Renewable energy | ||

| Efficient lighting | ||

| Use of efficient devices | ||

| Green procurement of products | ||

| Use of chemicals/pesticides | ||

| Limitation of food waste | ||

| Building envelope insulation | ||

| Building heating cooling control | ||

| Environmental information to guests | ||

| Environmental training to staff | ||

| Green environment/outdoor areas | ||

| Biodiversity conservation | ||

| Visits to natural sites | ||

| Accessibility on sustainable/public transport | ||

| Reduce CO2 and other greenhouse emissions | ||

| Evaluation criteria relate to Economy | Local employment | |

| Local purchasing | ||

| Local products consumption | ||

| Support of local entrepreneurs | ||

| Information to guests on responsible consumption | ||

| Evaluation criteria related to the social focus | Employment equity | |

| Community support | ||

| Social/community services or engagement activities | ||

| Raise guests awareness on tourism sustainable development | ||

| Raise staff awareness on tourism sustainable development | ||

| Protection/dissemination of local culture and heritage | ||

| Other evaluation criteria | ||

| Are the criteria set/defined by a third party, independent from the ecolabel issuer? | Yes | |

| Partially | ||

| No | ||

| * What is the availability of the label’s criteria and methodology? | Fully published/available | |

| Partially published/available | ||

| Restricted access/availability | ||

| Not available | ||

| * Audit procedure type | Third party audit (external and independent entity) Issuer entity audit (entity that issues the label) Internal audit (self-evaluation) Other | |

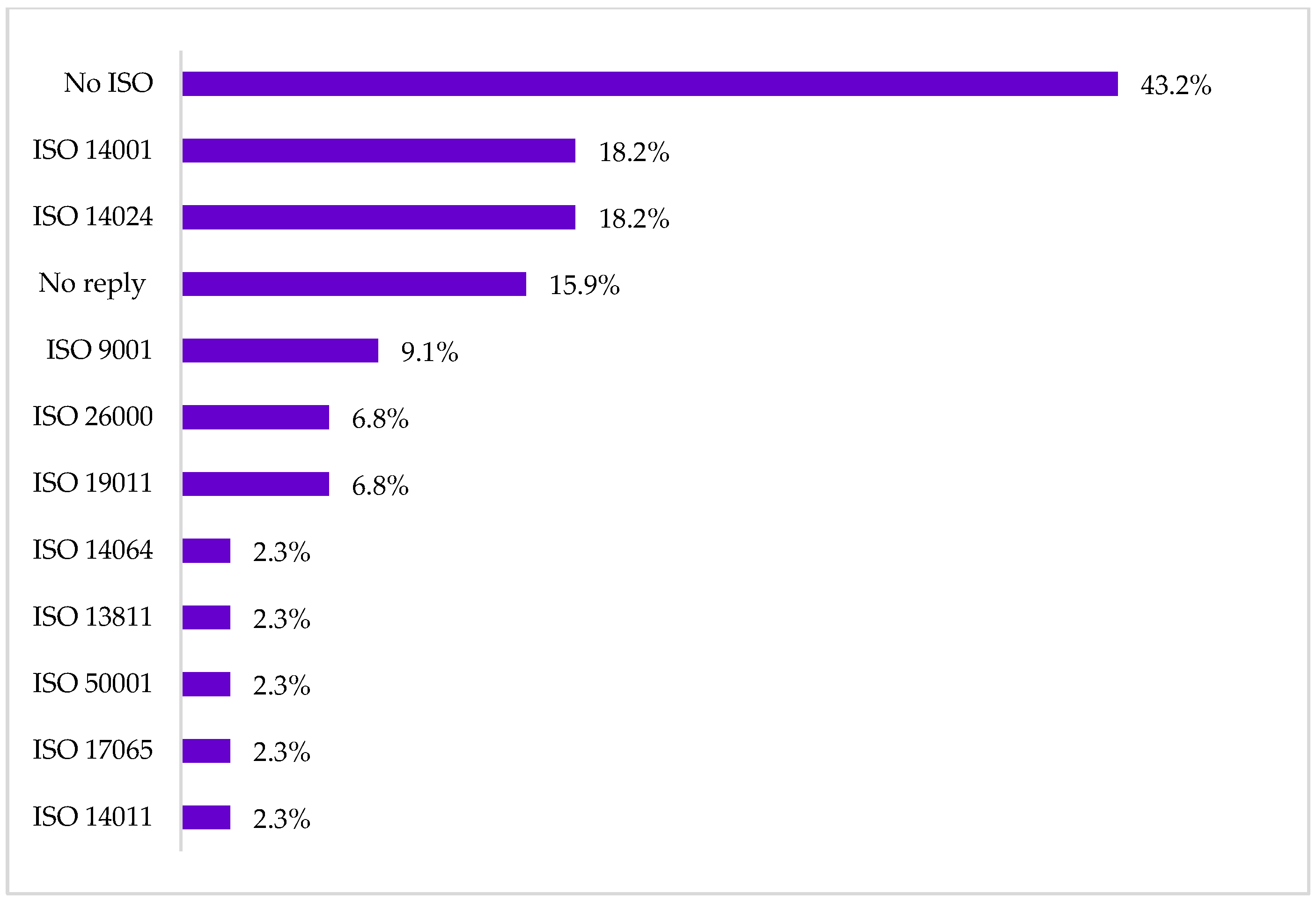

| Certification ISO standards | ISO 14001—Environmental Management | |

| ISO 14024—Type I Environmental labelling | ||

| Other | ||

| None | ||

| * Duration/validity of the certification | 1 year | |

| 2 years | ||

| 3 years | ||

| 4 years or more | ||

| Unlimited duration | ||

| Other | ||

| Fees charged for issuing the ecolabel (approximate or interval in €) | ||

| Renewal fee (approximate or interval in €) | ||

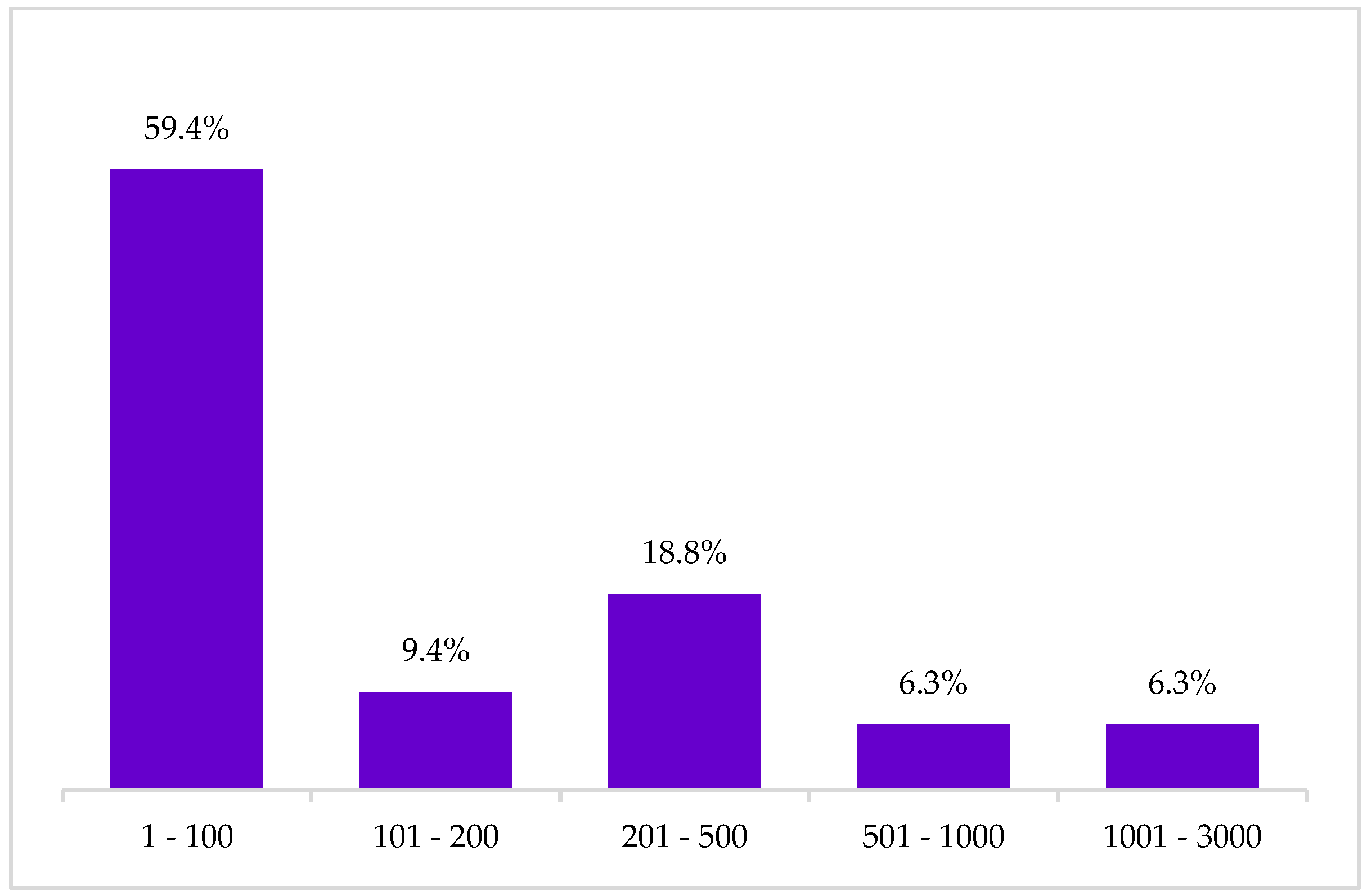

| 4. Information about certified accommodations | Number of tourism serviced awarded (approx.) | |

| Number of tourism services awarded in EU-27 countries (approx.) | ||

| 5. Ecolabel contact | ||

| Position |

References

- Ayuso, S. (2007). Comparing voluntary policy instruments for sustainable tourism: The experience of the spanish hotel sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(2), 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q. B., Shah, S. N., Iqbal, N., Sheeraz, M., Asadullah, M., Mahar, S., & Khan, A. U. (2023). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(3), 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbulescu, A., Moraru, A.-D., & Duhnea, C. (2019). Ecolabelling in the romanian seaside hotel industry—Marketing considerations, financial constraints, perspectives. Sustainability, 11(1), 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilynets, I., Knezevic Cvelbar, L., & Dolnicar, S. (2023). Can publicly visible pro-environmental initiatives improve the organic environmental image of destinations? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(1), 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla Priego, M. J., Najera, J. J., & Font, X. (2011). Environmental management decision-making in certified hotels. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(3), 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookdifferent. (2025). Eco-certified hotel. Available online: https://www.bookdifferent.com/en/eco-certified-hotels// (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Bučar, K., Van Rheenen, D., & Hendija, Z. (2019). Ecolabelling in tourism: The disconnect between theory and practice. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 67(4), 365–374. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/230634 (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Claver-Cortés, E., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Pereira-Moliner, J., & López-Gamero, M. D. (2007). Environmental strategies and their impact on hotel performance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. (2022). European agenda for tourism 2030—Council conclusions. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15441-2022-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Dabeva, T. (2013, October 2–4). The role of international eco certification system in the hotel industry. Sixth Black Sea Tourism Forum (pp. 149–160), Varna, Bulgaria. [Google Scholar]

- Dief, M. E., & Font, X. (2010). The determinants of hotels’ marketing managers’ green marketing behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(2), 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S., Ivanov, S., Magliano, F., & Ivanova, M. (2017). Motivation, costs and benefits of the adoption of the European ecolabel in the tourism sector: An exploratory study of Italian accommodation establishments. Business & Management Compass, University of Economics Varna, 61(1), 83–95. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/vrn/journl/y2017i1p83-95.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Ecobnb. (2025). Green labels for sustainable tourism: An all in one Guide. Available online: https://ecobnb.com/blog/2021/07/green-labels-sustainable-tourism-guide/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Ecolabel Index. (2025). Available online: https://www.ecolabelindex.com/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Commission. (2017). Commission decision (EU) 2017/175 of 25 January 2017 on establishing EU ecolabel criteria for tourist accommodation. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32017D0175 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- European Commission. (2022). Directorate-general for internal market, industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs. Transition pathway for tourism. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2873/344425 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- European Commission. (2023). Proposal for a directive of the European parliament and of the council on substantiation and communication of explicit environmental claims (green claims directive). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52023PC0166 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Commission. (2024). EU ecolabel facts and figures. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel-home/business/ecolabel-facts-and-figures_en (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Commission. (2025a). Directorate-general for environment. EU ecolabel. The official European Union voluntary label for environmental excellence. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel_en (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Commission. (2025b). EU ecolabel product groups and criteria. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Commission. (2025c). The EU tourism dashboard. Available online: https://tourism-dashboard.ec.europa.eu/?lng=en&ctx=tourism (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2024). Directive (eu) 2024/825 of the European parliament and of the council amending directives 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU as regards empowering consumers for the green transition through better protection against unfair practices and through better information. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L_202400825 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- European Travel Commission. (2019). Report on European sustainability schemes and their role in promoting sustainability and competitiveness in european tourism (ETC Market Intelligence Report). Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/european-sustainability-schemes/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Font, X. (2002). Environmental certification in tourism and hospitality: Progress, process and prospects. Tourism Management, 23(3), 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Ecotourism Network. (2025). Available online: https://www.globalecotourismnetwork.org/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Google Trips—List of Ecolabels. (2025). Available online: https://www.google.com/travel/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Green Travel Index. (2025). Available online: https://greentravelindex.com/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- GSTC Recognized Standards for Hotels. (2025). Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/gstc-criteria/gstc-recognized-standards-for-hotels/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Hamele, H. (2001). Ecolabels for tourism in Europe: The European ecolabel for tourism? In Tourism ecolabelling: Certification and promotion of sustainable management (pp. 175–188). CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2015). ISO 14001:2015. Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/60857-v2.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2018). ISO 14024:2018. Environmental labels and declarations—Type I environmental labelling—Principles and procedures. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72458.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2019). Environmental labels. Available online: https://www.iso.org/publication/PUB100323.html (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2022). ISO 14020:2022. Environmental statements and programmes for products—Principles and general requirements. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/79479.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Karlsson, L., & Dolnicar, S. (2016). Does eco certification sell tourism services? Evidence from a quasi-experimental observation study in Iceland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(5), 694–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelinfo.ch. (2025). Available online: https://www.labelinfo.ch/de (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Mak, A. H. N., & Chang, R. C. Y. (2019). The driving and restraining forces for environmental strategy adoption in the hotel Industry: A force field analysis approach. Tourism Management, 73, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikayilov, J. I., Mukhtarov, S., Mammadov, J., & Azizov, M. (2019). Re-evaluating the environmental impacts of tourism: Does EKC exist? Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(19), 19389–19402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, D., & Hamele, H. (2014). Sustainability in tourism: A guide through the label jungle. Roundtable Human Rights in Tourism. Naturefriends International, Berlin, Germany. Available online: https://www.nf-int.org/sites/default/files/infomaterial/downloads/2018-08/Labelguide_Dritte_Auflage_ENG_2016.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- OECD. (2008). Promoting sustainable consumption: Good practices in OECD countries. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preziosi, M., Tourais, P., Acampora, A., Videira, N., & Merli, R. (2019). The role of environmental practices and communication on guest loyalty: Examining EU-Ecolabel in Portuguese hotels. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome, A. (2002). Tourism ecolabelling: Certification and promotion of sustainable management. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberger, H., Galvez Martos, J. L., & Styles, D. (2013). Best environmental management practice in the tourism sector: Learning from frontrunners. Joint Research Centre, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism 2030 DestiNet Services. (2025). Available online: https://destinet.eu/who-who/civil-society-ngos/ecotrans/publications/guide-through-label-jungle-1 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Velaoras, K., Menegaki, A. N., Polyzos, S., & Gotzamani, K. (2025). The role of environmental certification in the hospitality industry: Assessing sustainability, consumer preferences, and the economic impact. Sustainability, 17(2), 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, R., Hamele, H., Balas, M., Denman, R., Pezzano, A., Sillence, G., Reiner, K., Grebenar, A., & Lawler, M. (2018). Research for TRAN committee—European tourism labelling. European parliament, Policy department for structural and cohesion policies. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/617461/IPOL_STU(2018)617461_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Wilde Tippett, A., Ragni Ytterdal, E., & Øyvind, S. (2020). Ecolabelling for tourism enterprises: What, why and how. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Available online: https://www.waddensea-worldheritage.org/ecolabelling-tourism-enterprises-what-why-and-how (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Yılmaz, Y., Üngüren, E., & Kaçmaz, Y. Y. (2019). Determination of managers’ attitudes towards eco-labeling applied in the context of sustainable tourism and evaluation of the effects of eco-labeling on accommodation enterprises. Sustainability, 11(18), 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iodice, S.; Batista e Silva, F.; Romanillos, G.; Moya-Gómez, B.; Morrissey, A.-M.; Ala-Mutka, K.; Konitz-Budzowska, D. The Place and Role of Environmental Labels for Tourist Accommodations: A Survey-Based Characterisation for the European Union. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010022

Iodice S, Batista e Silva F, Romanillos G, Moya-Gómez B, Morrissey A-M, Ala-Mutka K, Konitz-Budzowska D. The Place and Role of Environmental Labels for Tourist Accommodations: A Survey-Based Characterisation for the European Union. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleIodice, Silvia, Filipe Batista e Silva, Gustavo Romanillos, Borja Moya-Gómez, Anne-Marie Morrissey, Kirsti Ala-Mutka, and Daria Konitz-Budzowska. 2025. "The Place and Role of Environmental Labels for Tourist Accommodations: A Survey-Based Characterisation for the European Union" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010022

APA StyleIodice, S., Batista e Silva, F., Romanillos, G., Moya-Gómez, B., Morrissey, A.-M., Ala-Mutka, K., & Konitz-Budzowska, D. (2025). The Place and Role of Environmental Labels for Tourist Accommodations: A Survey-Based Characterisation for the European Union. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010022