Abstract

Battlefield tourism is an increasingly popular form of travel, where visitors seek to connect with history and cultural heritage by exploring locations famous for their battles. Battle tourism is found in different places, specifically, those involved in ancient world battles. Research has shown that battle tourism has a significant impact on local economies as visitors spend money in hotels, restaurants, and shops. It has also proven to be an effective tool for education, allowing visitors to learn about history in an interactive and exciting manner. However, there are also concerns about the impact of battle tourism on historic sites and how cultural sensitivity is managed. Our research discusses battle tourism, including its economic and educational impacts, as well as the challenges and opportunities in managing tourism at these historic sites. In addition, it discusses how battlefield tourism relates to other types of historical tourism and how visitors’ experiences in these places can be enhanced. With these objectives, the main success stories referenced in the academic bibliography have been analyzed from a systematic review conducted using the PRISMA methodology.

1. Introduction

Despite its controversial nature, dark tourism has become an increasingly popular form of travel in recent years, with millions of people around the world visiting sites associated with death and suffering every year. Dark tourism is a unique form of tourism that involves travel to sites associated with death, suffering, and tragedy. It has been described using various terms, including black spots tourism, thanatourism, and morbid tourism. Among the abundant bibliography on dark tourism, we can mention, as the most referenced articles according to the main indexed databases, the works of Stone and Sharpley [1,2,3], Strange and Kempa [4], Biran et al. [5], Light [6], and Cohen [7]. There are also very relevant books [8,9].

However, the term remains poorly conceptualised and theoretically fragile [5]. Vanneste and Winter (2018) addressed the debate surrounding the taboo of death and propose potential boundaries for forms of tourism that involve the deceased and sites of death. They also examined how taboos are part of mediation processes in societies and the role of mediating agencies in controlling notions of socially acceptable behaviour in order to prevent deviant behaviour and punishment [10].

Dark tourism includes visits to locations such as battlefields, memorials, prisons, and disaster zones. Recently, the use of natural language processing has allowed for the identification of activities that were rarely considered previously as forms of dark tourism, such as urban exploration and ghost hunting [11]. Although it is debated whether dark tourism can be considered a historical phenomenon, the provision of dark attractions or experiences has grown rapidly, and an increasing number of people are eager to promote or profit from “dark” events as tourist attractions [12], to the point that the most recent academic literature wonders whether feeling well-being, as a result of dark tourism, is a way of trivialising horror [13]. In fact, as Korstanje has pointed out [14], not all dark shrines or sites welcome tourists, and some are reluctant to mass tourism.

Although some critics argue that dark tourism is exploitative or disrespectful, others point out that it can serve important educational and memorialisation purposes. A “hot interpretation” approach focuses on the emotional or affective dimension of the human experience, offering tourists a significant dark tourism experience and facilitating community healing by providing a deep understanding and insight into a tragic event [15]. For example, visits to sites associated with war and conflict can provide opportunities for reflection and reconciliation, while visits to sites associated with natural disasters or human rights abuses can raise awareness about the need for disaster preparedness or social justice. However, visiting historically authentic sites or viewing authentic relics does not necessarily help tourists understand the events that took place, and too much emphasis on museum displays can risk distancing and objectifying the past [7]. Recent studies have also focused on children’s experiences of dark tourism [16].

Tourism associated with war sites has become a major category of tourist attractions and is considered part of dark tourism, allowing people to experience death and destruction as a tourist experience. Battlefield tourism emerged in the early 20th century, and famous battlefields such as Waterloo and Normandy have become cultural heritage and memory sites with attractions that include geographical and tangible elements of the war legacy, such as cemeteries, museums, and trenches [17]. Experiences in lesser-known continents such as Africa have also been recently analyzed [18]. As new forms of conflict have emerged, the definition of a battlefield has expanded to encompass sites such as the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001 [19] and areas affected by insurgent attacks and armed resistance. Despite ongoing conflicts, tourists still visit countries experiencing turmoil, including Israel during the Palestinian Intifada, London amid IRA bombing campaigns, and Nepal during the Maoist insurgency [20]. Not only violent places are visited, but those related to economic issues also attract tourists [21].

These sites offer opportunities for visitors to engage with history and culture, facilitating a deep understanding of past events and promoting healing in communities affected by tragedy. Battlefield tours, for example, offer opportunities for validation, personal reflection, and commemoration driven by personal and collective remembrance and a moral obligation [22]. This tourism offers sites of cultural memory where memory becomes institutionalised through cultural means, such as commemorative rituals, memorials, and museums. The proliferation of memorials and re-enactments raises questions of authenticity but ultimately aims to visualise an event that lives in its memorialisation [23].

Battlefield tourism has also been proven to be an effective tool for education, allowing visitors to learn about history in an interactive and exciting manner; however, it is necessary to highlight the difficulty of achieving successful learning outcomes during short talks, or “stands”, which are the main forum for instruction during battlefield tours [24]. Even if the events occurred more than a century ago, the emotional impact of the experience can still be profound due to the correct preservation of the dark attributes [25].

Despite its many benefits, there are also concerns regarding the impact of battle tourism on historic sites and how cultural sensitivity is managed. The rise in popularity of battlefield tourism has led to an increase in the number of visitors to these sites, which can put pressure on the sites themselves and the surrounding communities. It is essential to understand and manage these impacts effectively to ensure that these historic sites are preserved for future generations: it has been suggested that, instead of offering unrelated modern entertainment or commodified cultural experiences, these sites should develop partnerships aimed at promoting reconciliation and provide alternative locally meaningful experiences in line with the transformative view [26].

Studies of battlefield tourism in specific contexts have been conducted, including, for example, tourism to First and Second World War battlefields, Gallipoli, Vietnam battlefield tours and sites, and Waterloo battlefields. These studies highlight the importance of interpretation and the emotional and affective dimension of human experience in dark tourist experiences [8,22,27,28,29]. Throughout the past century, successful exhibitions of war paintings and relics drew large numbers of visitors, with some exhibitions featuring larger artefacts, such as artillery pieces and aeroplanes. Scholars do not agree on how tourist sites become sacred since many different factors contribute to the process [30]. The exhibitions provided an opportunity for people to remember and mourn the dead, with war memorials described as sacred places and people who visited them described as pilgrims [31]. Over the years, research has also shown that battlefield tourism has a significant impact on local economies as visitors spend money in hotels, restaurants, and shops. France can be underlined as a sample: its tourism industry is crucial for its economy and cultural development, with battlefield tourism providing a niche market that has encouraged the revitalisation of deindustrialised areas [32].

Our research aims to explore the phenomenon of battlefield tourism in more detail, including its economic and educational impacts. We will also examine the challenges and opportunities associated with managing tourism at these historic sites, particularly in terms of preserving cultural heritage and managing visitor expectations. In addition, we will discuss how visitors’ experiences in these places can be enhanced. To achieve these objectives, we will analyze the main success stories referenced in the academic bibliography related to battlefield tourism. We will examine case studies of successful battlefield tourism destinations, looking at how they have managed to balance the needs of visitors with the preservation of cultural heritage. By doing so, we hope to identify best practices and provide recommendations for managing battlefield tourism in a way that is sustainable, responsible, and respectful of cultural heritage. In general, this research aims to contribute to the development of a more nuanced understanding of battlefield tourism and its potential as a tool for education, economic development, and cultural preservation.

Three main contributions can be highlighted. First, while it is true that the topic of battlefield tourism has been investigated to some extent, there is still much that is not fully understood about this phenomenon, particularly in terms of the economic and educational impacts of battlefield tourism and the challenges and opportunities associated with managing tourism at these historic sites. This research aims to provide a more comprehensive analysis of battlefield tourism and identify best practices for managing it sustainably and respectfully. Secondly, this research contributes to the literature on dark tourism, which is an increasingly popular and important field within tourism studies. The unique and often controversial nature of dark tourism has led to significant interest from researchers and practitioners, and this research adds to the body of knowledge on this topic. Finally, the findings of this research will be of interest to a wide range of stakeholders, including policymakers, heritage site managers, and tourism industry practitioners.

By explicitly linking the findings of this research to a managerial perspective and providing specific recommendations for tourism industry practitioners and heritage site managers, this study offers practical solutions to the challenges posed by battlefield tourism. The recommendations provided in this research can be used to guide the development of sustainable and responsible tourism practices on battlefield sites and to ensure that cultural heritage is preserved for future generations.

The manuscript is organised into four main sections. Section 1 provides a background to the problem and a context for the study. Section 2 elaborates on the methodology used to conduct the study; this section provides an overview of the research design, including data collection methods and data analysis techniques. Section 3 presents and analyzes the findings of the study and includes a discussion of the results and focuses on their implications. Finally, in Section 4, the paper concludes with a summary of the main findings and their implications; this section also highlights the contributions of the research, its limitations, and potential areas for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The presented research follows a systematic review methodology, which is a rigorous and structured approach to synthesising knowledge on a specific topic. Systematic reviews use explicit and comprehensive methods to identify, select, and evaluate relevant primary research studies to answer a specific research question. The aim is to provide a transparent and traceable process that increases the quality and reliability of the results [33]. Literature reviews play a crucial role in assessing the current state of a field and providing direction for its future development [34]

To conduct this systematic review, the researchers followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol [35], which was recently updated [36], and which sets the criteria for high-quality scientific publications. As established, research was characterised by the transparency and clarity of purpose [37,38], following the four-stage process of identification of relevant studies, selection of studies, mapping of data, and synthesis and reporting of results.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified and documented. This study only considered research studies that were published in scientific journals, books, and book chapters. Conference proceedings were not included in the study because they were considered ongoing investigations whose final results usually appear in articles. Additionally, official literature, status reports, and opinion pieces in magazines were not considered, as the study aimed to identify and analyze proposals only based on scientific studies.

A thorough search of the Scopus and Web of Science databases was conducted in April 2023. The search strategy was adapted for each included database. For example, the search equation finally used on Scopus, including limiters to consider the inclusion and exclusion criteria, was as follows: TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “battlefield tourism” ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , “ar” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , “ch” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , “bk” ) ).

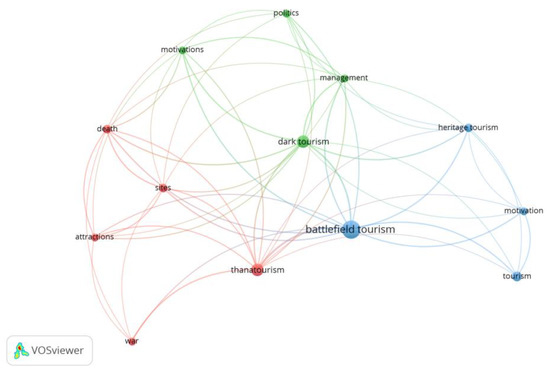

The search of the literature turned up 124 investigations. The information specialist on the study team exported the results to Zotero and deleted any duplicates. A total of 34 citations were rejected in the identification and removal of duplicate studies while retaining 90 articles. Their keywords were grouped with the help of VOSviewer to create a first conceptual map grouped by clusters of the selected scientific production (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

First conceptual map.

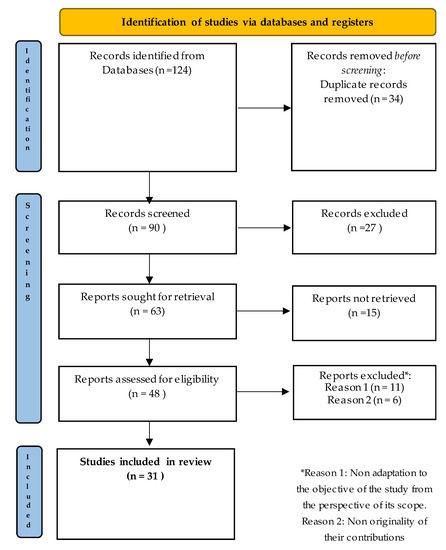

After a pilot test, the titles and abstracts were then evaluated by the two researchers against their adaptation to the study’s purpose from the standpoint of its scope, choosing those with broadly generalisable contributions. The researchers kept 63 papers: 48 of them were retrieved. The same reviewers carefully evaluated the complete texts of the chosen citations. Decisions then were based on the originality of their contributions [39] and their adaptation to the objective of the study. Once this critical review was carried out, 17 articles were disregarded as the result of this complete text screening; as a result, 31 papers were part of the qualitative synthesis.

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 2) that depicts the inclusion decision flowchart with the steps in the process presents the search results and the study inclusion procedure.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Data extraction and synthesis were performed on each of the included studies. They were combined by the reviewers in Table 1 with all pertinent information. The study team decided that the following extraction fields should be used: title, first author, journal or book, year, keywords, and main contribution.

Table 1.

Documents part of the qualitative synthesis.

To verify that their method of data extraction was consistent with the research question and the goal, the researchers separately extracted data from the first 10 trials and combined them. Discussion between reviewers was used to settle any disputes that may have arisen.

3. Discussion, Challenges, and Opportunities for Battlefield Tourism

With the assembly of the findings and their classification based on similarity in meaning, this procedure required the synthesis of findings to produce a set of statements that represent that aggregate. To create a single comprehensive collection of synthesised findings that can serve as the foundation for evidence-based practice, these categories were then submitted for synthesis. The results are presented in a narrative style in cases where textual pooling was not feasible. In the synthesis, only conclusive and reliable findings were used.

3.1. Economic Impact

Historical battlefield tourism generates significant economic benefits through tourist spending and job creation. This kind of cultural tourism can also lead to the development of infrastructure and services that benefit both tourists and local residents [40]. Already in 2004, Gatewood and Cameron reported that the total economic impact of Gettysburg National Military Park was USD 118.8 million per year. This included a multiplier effect of 2.24, bringing the total to USD 265.5 million per year. The economic impact was generated by visitor spending, Park Service expenditures, and tax revenues. The study also found that the park supported over 2000 jobs in the local area [41]. Analogously, Lee (2015) highlighted that the Keelung Ghost Ceremony attracts one million visitors per year and generates 81 million New Taiwan Dollars on average [42]. Melstrom, ten years ago, indicated an average individual willingness to pay for a battlefield trip ranging from about USD 8 to USD 25, depending on the site [43]. In addition, niche tourism types, such as battlefield tourism, can promote tourism activities during low tourism seasons, which can help to support local economies; however, it requires a balance between economic benefits and preserving the site’s integrity, and sustainable practices and cultural preservation are necessary to maximize the positive impact.

3.2. Visitor Expectations

The research discusses the importance of meeting visitor expectations in battlefield tourism, including providing accurate information and interpretation, as well as creating emotional connections to the site [44]. The landscaping of these sites can provoke interesting and diverse interpretations, leading to a multi-layered remembrance. Vanneste and Winter (2018) recommended that governance and policy should be connected from the “as is” perspective, taking into account the attitudes and choices of visitors [10].

Battlefields are one of the most visited thanatourist sites, but visitors may not consider themselves as ‘dark tourists’ or “thanatourists” [45]. Visitors come to these sites with a range of motivations and preconceptions, including a desire to learn more about the history of the site, pay their respects to fallen soldiers, and connect with their national identity. Veterans, leisure visitors, collectors, preservationists, and educational groups are the observable types of battlefield tour visitors [45]. Le and Pearce (2011) described three groups of visitors to the DMZ in Vietnam: the first group is the smallest and consists of battlefield tourism enthusiasts who have a personal connection to the Vietnam War and tend to be older; the second group is the opportunists who are opportunistic in their decision to visit and tend to be younger, well-educated, and on holiday in Vietnam; the third and largest group are the passive tourists who are on holiday in Vietnam and are more likely to have come on a group bus tour, with many being young, well-educated, and visiting Vietnam for the first time [46].

Some visitors also come with preconceived notions about what they will see and experience on-site, based on family stories or media representations; this occurs, for example, among visitors to Gallipoli [47]. Hyde and Harman (2011) outlined various motives for a secular pilgrimage to the Gallipoli battlefields, including the search for spirituality, novelty, relationship enhancement, adventure, escape, and experiencing worldly pleasures. Their study also noted that young Australians and New Zealanders residing in the UK have leisure tourism motives for visiting the site, while some travellers may visit to honour the memory of a family member who fought and died there [28]. Furthermore, the pilgrimage to Gallipoli can have a profound personal meaning for some travellers, and families can seek closure by visiting the gravesite of a fallen soldier. Psychographic segmentation based on the perception of these sites can inform promotional efforts, with intensive visiting experiences recommended for those who perceive the site as part of their own heritage, and guided tours recommended for those who do not [27].

3.3. Best Practices

Chela and Griffin (2013) emphasise the importance of guides in helping visitors connect with the site physically, intellectually, and emotionally. Chambers (2012) stressed the importance of people interacting with specific battlefields, not just listening to or reading speeches and ceremonies, in constructing memories of war [48]. By tailoring the interpretation to meet the needs and interests, guides can help visitors connect with the site in personal and emotional ways that improve their understanding of its historical significance [47]. Highlighting connections between the personal history and the destination has been identified as an effective interpretation strategy for tour guides [49]. The dominance of audiovisual displays reflects the need for visitors to be actively engaged in the interpretational process. The visual experience is paramount, but interpretation should be understood as a more multisensory experience [50].

Zhang proposed a conceptual framework for branding initiatives in battlefield tourism, which includes top-down efforts by tourism planners and bottom-up contributions by local entrepreneurs, residents, and tourists. His framework views this brand as a fluid and dynamic idea that is constantly evolving through ongoing negotiations between state-mandated branding efforts and the input of locals and visitors (26).

Lee (2015) insisted that managers of battlefield attractions must implement the story marketing strategy, which encourages tourists to visit the attractions, enhances their emotional experience, elicits curiosity regarding history, and increases their behavioural intention to revisit [42]. Some site’s staff uses storytelling as a way to engage visitors and create a more immersive experience [51]. The fusion of place and narrative is important in providing visitors with a meaningful experience [50]. All aspects of the tour, from accommodation through to the stories told by the guides, must be tailored to the differing requirements of a grieving relative on the a ‘pilgrimage’ on the one hand and someone who has a special interest in warfare and military history on the other [52]. Tour guide interpretation affects tourist satisfaction and subsequently influences destination loyalty for tourists. Tourists who perceive high playfulness and flow have stronger correlations between tour guide interpretation, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty [49].

The tourism industry’s craving for new locations has prompted a reevaluation of the battlefield concept, embracing both ‘real’ and ‘play’ aspects. The ’real’ refers to the actual site of battle, while the ‘play’ includes reenactments of historical battles and alternative history scenarios. This new perspective has become a significant attraction in numerous countries [20]. Reenactments are organised to promote battlefields and share knowledge from the past, but also to fulfill and satisfy the needs of the reenactors’ community itself. Noivo et al. (2021) suggested that reenactment, and living history as part of the creative experience that promotes an interactive, diverse, and more enriching contact with the local culture, allows for all participants a cross-cultural experience where a deep understanding of communities and a common cultural awareness are widely promoted [53]. In fact, visitors may want more interactive experiences or opportunities to engage with local communities [22]. This can extend the tourist season, promote a tourist destination, and generate extra money for an area or local communities [54].

The preservation of battlefields as national parks or monuments, combined with effective museum networks, can help share the stories and impact of past conflicts with future generations [20]. Visual ethnography can be used to enhance tourism learning experiences as well [55]; the authenticity of locale can be enhanced by the use of artefacts, but the replacement of reality with simulacra shows how the copy can often be as mystical as the real object [50].

3.4. Challenges

To effectively manage battlefield sites, site managers must address both the challenges and opportunities presented by the tourist-pilgrim dichotomy. By recognising and catering to the diverse motivations of visitors, managers can create experiences that balance different interests while preserving the cultural and historical significance of the sites. Providing educational programs, interpretive materials, and well-planned tours can allow visitors to connect with the past and gain a deeper appreciation of the importance [45].

Managing tourism in contexts where history is contested involves big challenges such as the ownership or control of public memory and the disconnect between the desire of tourists to express political identity and a country’s choice of how to (or not to) memorialise past events [56]. Due to its particularities, the Japanese case is very remarkable: the rewriting of history to deny wartime atrocities is a significant problem for the study of Japanese battlefield tourism. Cooper (2007) suggested that censorship imposed on traditional sources of information may have led to a desire among younger generations of Japanese to negate this censorship by visiting sites of historical significance [57]; taboos regarding the war are not as strong as they once were, and visitors are more willing to speak about and understand the experiences of both sides of the war [10]. The process of transforming specific areas into monuments can aid in establishing them as symbolic places, such as the Raimats battlefield in Spain: various events advocating for democratic values, freedom, and opposing fascism have taken place in the vicinity of the monument, which have been initiated by civil society [58].

Battlefield tourism, like all heritage tourism, is always about the ways in which the present makes use of the past [59]. Balancing nationalistic sentiments with a more cosmopolitan approach to heritage interpretation can be complicated [51], even if battlefield tourism has the ability to promote cross-cultural understanding and appreciation [40]. Tourism, as a peace-making activity, can allow people to see other cultures and learn to appreciate our similarities, rather than focus on our differences [60]. McDonald (2019) described how the modern Japanese state created places of memory to foster a shared sense of identity and collective memory among the newly constituted Japanese nation [61]. Brown and Ibarra (2018) explored how visiting memorials associated with the Spanish Civil War can reenergize political commitment and contribute to knowledge on how identity shapes and is shaped by tourist activity [56]. Partnerships aimed at promoting reconciliation can also provide alternative locally meaningful experiences [26]. A significant risk is that organised battlefield tourism may trivialise both the idea of pilgrimage and the wartime sacrifices of the dead [30].

One of the major challenges in preserving battlefields is the encroachment of urbanisation. Many historic sites, such as those from the American Civil War, are being lost or threatened by redevelopment. However, the increasing popularity of battlefield tourism presents opportunities to raise awareness and generate resources for preserving these sites as important cultural and historical landmarks [20]. Despite the unexpectedly positive outcomes of dissonance management on battlefields, heritage management could nevertheless be improved and designed in a sustainable manner [27]. The participation of local communities and the promotion of cooperation networks facilitate the structured and sustained development of a battlefield tourism attraction, with creative tourism as a key factor [53].

4. Conclusions

This research aimed to explore the phenomenon of battlefield tourism in detail, including its economic and educational impacts as well as the challenges and opportunities associated with managing tourism at these historic sites. Our findings indicate that battlefield tourism generates significant economic benefits through tourist spending and job creation, but also poses challenges in preserving cultural heritage and managing visitor expectations. Best practices for battlefield tourism include employing knowledgeable tour guides, using storytelling to engage visitors, and promoting interactive and immersive experiences such as re-enactments. By implementing these best practices, industry professionals can better manage battlefield tourism and promote a more nuanced understanding of this form of travel.

Visitors come to battlefield sites with a variety of motivations and expectations that should be considered when designing tours and promotional efforts. Meeting visitor expectations can be achieved by providing accurate information and interpretation, creating emotional connections to the site, and offering tailored experiences to different visitor groups.

Managing tourism in contested historical contexts is a complex challenge as it involves balancing nationalistic sentiments with a more cosmopolitan approach to heritage interpretation. Battlefield tourism has the potential to promote cross-cultural understanding and appreciation but can also run the risk of trivialising the sacrifices made during wartime. Partnerships aimed at promoting reconciliation and involving local communities can provide alternative, meaningful experiences for visitors.

Limitations of this study include the reliance on the existing literature and case studies, which may not capture the full range of battlefield tourism experiences and best practices. Future research could involve primary data collection through surveys, interviews, or observational studies to gain deeper insights into visitor motivations, expectations, and experiences. Additionally, the investigation of more diverse battlefield sites across different historical contexts and regions would help provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities in managing this form of tourism.

In conclusion, battlefield tourism presents both economic and educational benefits, as well as challenges related to cultural heritage preservation and visitor expectations management. By adopting best practices and promoting sustainable, responsible, and respectful approaches to battlefield tourism, this form of travel can positively contribute to local economies, education, and cultural preservation. Future research should continue to explore innovative ways to improve visitor experiences and promote sustainable management practices in this growing tourism sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-Á.G.-M.; methodology, M.-Á.G.-M.; software, M.-Á.G.-M.; validation, M.-Á.G.-M. and A.-J.G.-M.; formal analysis, M.-Á.G.-M.; investigation, M.-Á.G.-M. and A.-J.G.-M.; data curation, M.-Á.G.-M. and A.-J.G.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-Á.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.-J.G.-M.; visualization M.-Á.G.-M.; supervision, M.-Á.G.-M.; project administration, M.-Á.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharpley, R.; Stone, P.R. (Eds.) Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism; Multilingual Matters Ltd.: Clevedon, UK, 2009; pp. 1–275. ISBN 978-1-84541-116-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P.R. Dark tourism and significant other death: Towards a Model of Mortality Mediation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1565–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.; Sharpley, R. Consuming Dark Tourism: A Thanatological Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, C.; Kempa, M. Shades of Dark Tourism—Alcatraz and Robben Island. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biran, A.; Poria, Y.; Oren, G. Sought experiences at (dark) heritage sites. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Progress in Dark Tourism and Thanatourism Research: An Uneasy Relationship with Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.H. Educational Dark Tourism at an in Populo Site. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkranikal, J.; Yang, Y.S.; Powell, R.; Booth, E. Motivations in Battlefield Tourism: The Case of ‘1916 Easter Rising Rebellion’, Dublin. In Proceedings of the Tourism and Culture in the Age of Innovation; Katsoni, V., Stratigea, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Tzanelli, R. Thanatourism and Cinematic Representations of Risk: Screening the End of Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste, D.; Winter, C. First World War Battlefield Tourism: Journeys out of the Dark and into the Light. In The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 443–467. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Egger, R. Looking behind the Scenes at Dark Tourism: A Comparison between Academic Publications and User-Generated-Content Using Natural Language Processing. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Stone, P.R. (Eds.) The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism; Aspects of Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK; Buffalo, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84541-115-2. [Google Scholar]

- Magano, J.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A.; Leite, Â. Dark Tourism, the Holocaust, and Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, M.E. Surfing in the Dark: Comparable Study Cases Between Ground Zero, US and Republica de Cromañón, Argentina. In Tourism Through Troubled Times; Korstanje, M.E., Seraphin, H., Wambugu Maingi, S., Eds.; Tourism Security-Safety and Post Conflict Destinations; Emerald Publishing Limited: Somerville, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 75–91. ISBN 978-1-80382-311-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, E.-J.; Scott, N.; Lee, T.J.; Ballantyne, R. Benefits of Visiting a ‘Dark Tourism’ Site: The Case of the Jeju April 3rd Peace Park, Korea. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.M.; Stone, P.R.; Price, R.H. (Eds.) Children, Young People and Dark Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-00-303219-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gülüm, E. Warfare, Oral Tradition, and Tourism: Valorization of the Folk Narratives About the Gallipoli Campaign. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/warfare-oral-tradition-and-tourism/www.igi-global.com/chapter/warfare-oral-tradition-and-tourism/292592 (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Stone, P.R. Dark Tourism and ‘Painful Pasts’ in Africa. In Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Africa; Routledge & CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9780367722241. [Google Scholar]

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. Heritage That Hurts: Tourists in the Memoryscapes of September 11; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux, B. Echoes of War: Battlefield Tourism. In Battlefield Tourism: History, Place and Interpretation; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tzanelli, R.; Korstanje, M.E. Tourism in the European Economic Crisis: Mediatised Worldmaking and New Tourist Imaginaries in Greece. Tour. Stud. 2016, 16, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, R.; Morgan, N.; Westwood, S. Visiting the Trenches: Exploring Meanings and Motivations in Battlefield Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, S.; Marques, M.J. Working Definitions in Literature and Tourism; CIAC—Centro de Investigação em Artes e Comunicação da Universidade do Algarve UAlg—Universidade do Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2022; ISBN 978-989-9127-03-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, N. Battlefield Tours and Staff Rides: A Useful Learning Experience? Teach. High. Educ. 2009, 14, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornarel, F.; Delacour, H.; Liarte, S.; Virgili, S. Exploring Travellers’ Experiences When Visiting Verdun Battlefield: A TripAdvisor Case Study. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 824–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey Lemelin, R.; Powys Whyte, K.; Johansen, K.; Higgins Desbiolles, F.; Wilson, C.; Hemming, S. Conflicts, Battlefields, Indigenous Peoples and Tourism: Addressing Dissonant Heritage in Warfare Tourism in Australia and North America in the Twenty-first Century. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Tsai, T.-H. Tourist Motivations in Relation to a Battlefield: A Case Study of Kinmen. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.F.; Harman, S. Motives for a Secular Pilgrimage to the Gallipoli Battlefields. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, C. Battlefield Visitor Motivations: Explorations in the Great War Town of Ieper, Belgium. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguin, S. “National Spain Invites You”: Battlefield Tourism during the Spanish Civil War. Am. Hist. Rev. 2005, 110, 1399–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D.W. Battlefield Tourism. Pilgrimage and the Commemoration of the Great War in Britain, Australia and Canada 1919–1939; A&C Black: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Foulk, D. The Impact of the “Economy of History”: The Example of Battlefield Tourism in France. Mondes Tour. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Ali, F. Advancing Knowledge through Literature Reviews: ‘What’, ‘Why’, and ‘How to Contribute’. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 481–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartling, L.; Guise, J.-M.; Kato, E.; Anderson, J.; Belinson, S.; Berliner, E.; Dryden, D.M.; Featherstone, R.; Mitchell, M.D.; Motu’apuaka, M.; et al. A Taxonomy of Rapid Reviews Links Report Types and Methods to Specific Decision-Making Contexts. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 68, 1451–1462.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.E.; Moher, D.; Clifford, T.J. Quality of Conduct and Reporting in Rapid Reviews: An Exploration of Compliance with PRISMA and AMSTAR Guidelines. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, H.M.; van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Inter-Professional Team’s Experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennell, C. Taught to Remember? British Youth and First World War Centenary Battlefield Tours. Cult. Trends 2018, 27, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatewood, J.; Cameron, C. Battlefield Pilgrims at Gettysburg National Military Park. Ethnology 2004, 43, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. The Relationships Amongst Emotional Experience, Cognition, and Behavioural Intention in Battlefield Tourism. ASIA Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melstrom, R. Valuing Historic Battlefields: An Application of the Travel Cost Method to Three American Civil War Battlefields. J. Cult. Econ. 2014, 38, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, Y.; Akbulut, O. Battlefield Tourism: An Examination of Events Held By European Institutions and Their Websites Related to Battlefields. Int. J. Contemp. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 73–123. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, F.; Sharpley, R. Battlefield Tourism: Bringing Organised Violence Back to Life. In The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 186–206. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.; Pearce, D. Segmenting Visitors to Battlefield Sites: International Visitors to The Former Demilitarized Zone in Vietnam. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheal, F.; Griffin, T. Pilgrims and Patriots: Australian Tourist Experiences at Gallipoli. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, T.A. Memories of War: Visiting Battlegrounds and Bonefields in the Early American Republic; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, N.-T.; Chang, K.-C.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Lin, J.-C. Effects of Tour Guide Interpretation and Tourist Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty in Taiwan’s Kinmen Battlefield Tourism: Perceived Playfulness and Perceived Flow as Moderators. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. From Hastings to the Ypres Salient: Battlefield Tourism and the Interpretation of Fields of Conflict. In Tourism and War; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- Daugbjerg, M. Not Mentioning the Nation: Banalities and Boundaries at a Danish War Heritage Site. Hist. Anthropol. 2011, 22, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noivo, M.; Dias, A.; Jimenez-Caballero, J. Connecting the Dots between Battlefield Tourism and Creative Tourism: The Case of the Peninsular War in Portugal. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 648–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Of Kaoliang, Bullets and Knives: Local Entrepreneurs and the Battlefield Tourism Enterprise in Kinmen (Quemoy), Taiwan. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylińska, D. “Nameless Landscapes”—What Can Be Seen and Understood on a Battlefield? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 787–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, R.; Shruiff, S.; Sampson, C.; Anderson, C.; Anderson, S.; Danahy, J.; Kolasa, Z.; Vantil, K.; Plows, M.; Smith, S.; et al. Videography and Student Engagement: The Potentials of Battlefield Tourism. Hist. Encount.-J. Hist. Conscious. Hist. Cult. Hist. Educ. 2016, 3, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Ibarra, K. Commemoration and the Expression of Political Identity. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Post-Colonial Representations of Japanese Military Heritage: Political and Social Aspects of Battlefield Tourism in the Pacific and East Asia. In Battlefield Tourism: History, Place and Interpretation; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, R.S.; Torruella, M.F.; Wilson, A.E.; Valle, G.S.; Pongiluppi, M.H. La The Battle of Fatarella, 1938. Museography, Iconography, Recreation and Memory. A Transversal Model of Didactic Research. Ebre 38 2018, 8, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V. “Another Weekend Away Looking for Dead Bodies…”: Battlefield Tourism on the Somme and in Flanders. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2000, 25, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, A.; Schänzel, H.; Lück, M. Reflections of Battlefield Tourist Experiences Associated with Vietnam War Sites: An Analysis of Travel Blogs. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K. War, Firsthand, at a Distance: Battlefield Tourism and Conflicts of Memory in the Multiethnic Japanese Empire. Jpn. Rev. 2019, 2019, 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).