1. Introduction

Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) are important pollinators that also serve as useful indicators of biodiversity [

1,

2]. They are among highly developed insects with remarkable diversity, with over 28,000 species being recorded worldwide [

3]. These are opportunistic foragers, frequently visiting a broad spectrum of flowering plants, thereby functioning as pollinators in the ecosystems [

4,

5]. Some butterflies are flower generalists, and others are flower specialists. However, research in this area has been minimal and primarily focused only on treatments of individual species or any specific groups of species rather than taking a broader approach [

6].

Currently, 692 species of butterflies have been documented in Nepal [

7]. The species richness of butterflies is influenced by the elevational gradients; towards higher elevations, especially above 3000 m, floral and butterfly diversity decreases [

8]. Nepal is divided into 10 butterfly zones: Western Terai, Eastern Terai, Western, Karnali, Gandaki, Trans-Himalayan, Kaski, Kathmandu Valley, Bagmati (Bagmati Province except Kathmandu Valley), and East [

9]. These divisions are based on geographical regions and river basins across the country. The geographic categorization was performed to make the data more precise and gather information from different ecological areas, especially those that haven’t been studied as much as others. In the southern region of the Kathmandu Valley, stretching from Godawari to Phulchowki Mountain, a high richness of butterfly species can be found. With over 150 species, the majority of them being forest dwellers, this area is recognized for its rich butterfly diversity [

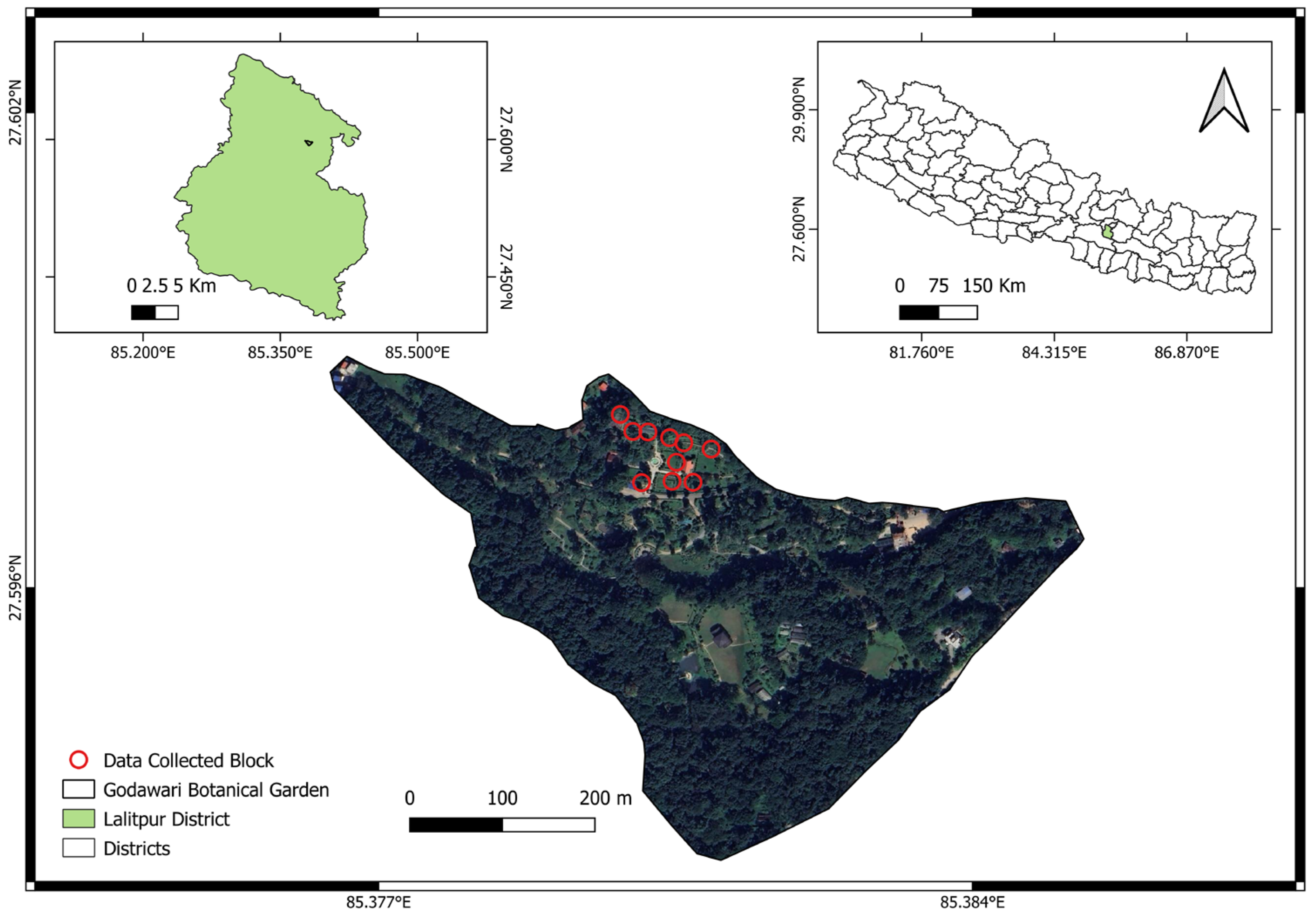

10]. The National Botanical Garden, Godawari, Lalitpur, Nepal (NBG), a managed botanical park at the base of the Phulchoki Mountain, also holds a high diversity of butterflies [

11]. Butterflies are one of the major attractions for the visitors of the NBG.

Various butterfly species demonstrate zonal distribution that is closely tied to strict seasonality and specific habitat preferences, including factors such as color, shape, nectar, size, and scent. Additionally, terrain complexity, climate, and types of vegetation are believed to significantly influence butterfly distribution [

12]. Their sensory modalities, for instance, visual and olfactory signals, help to differentiate between unique flower species with colors, morphologies, or fragrances [

13]. Studies concluded that the frequency with which butterflies visit flowers is significantly affected by particular attributes of the flowers themselves, such as flower colors, which are a crucial component for the various types of pollinators [

14,

15]. The study from Rupa Wetland of Nepal recorded that butterfly visits were considerably influenced by diverse plant categories, as well as color preference, with yellow, white, and purple colors over pink ones [

16]. Another study from Xiama Forest Farm, Gansu, China, reported that the preference for yellow flowers was higher compared to red, pink, purple, and white flowers, indicating that butterflies show distinct preferences for floral colors [

17]. The diversity of floral color is the result of the evolutionary history of the signaling mechanisms between plants and pollinators [

18]. Additionally, flower color plays a crucial role in helping pollinators detect flowers, making it an important attribute among floral traits [

19]. Multiple studies conclude that butterflies prefer mostly bright-colored flowers, i.e., yellow, in comparison to other colors [

20,

21].

The foraging patterns of butterflies are characterized by a variety of behaviors, including flower selection, time spent at a nectar source, and the total number of flowers visited in a foraging session [

22]. The foraging behavior of insects is shaped by the chemical and physical traits of plants. Additionally, the secondary metabolites present in them are believed to play a significant role in determining the quality and quantity of foraging resources [

23]. It is an ecologically important behavior exhibited by butterflies during pollination [

24]. For this, several researchers have studied butterfly–plant interactions [

16,

25,

26,

27]. The proboscis is an essential and highly adaptive organ in pollinators. Butterflies have a long and coiled proboscis, which they use to feed on nectar [

28]. Species with long proboscises feed on long corolla flowers, while those with a short proboscis feed on short corolla flowers [

29]. Insects rely on visual and olfactory signals to find suitable food sources with compatible flower morphology with the length of the corolla that suits its proboscis [

30,

31]. Different species of butterfly prefer different types of flowers [

32]. Numerous interactions between insects and flora for the purpose of pollination set perfect examples of coevolution in nature [

33]. Studies show that butterflies visit tree flowers less frequently in comparison to their visits to flowers of herbs and shrubs [

26]. Alien flowers are mostly preferred by butterflies with extended proboscis, as a high correlation was found between preference for alien flowering plants and proboscis length [

30].

Managed parks and botanical gardens are known to support a large number of pollinating insects, including butterflies [

34]. It is essential to understand the plant traits that determine butterfly diversity and affect the butterfly visitation frequencies to the flowers. This study explores the butterflies’ floral preferences, relying on traits like flower colors, origin, and shapes in the National Botanical Garden, Godawari, Lalitpur, Nepal. We hypothesized that (i) the light-colored flowers are visited more frequently by the butterflies than the dark ones; (ii) alien plants, being bright colored, are visited more frequently; and (iii) a positive association exists between the proboscis length of butterflies and the corolla tube length of flowers. We tested these hypotheses by direct observation of butterflies visiting the flowers in the National Botanical Garden, Lalitpur, Nepal. Such studies are crucial to protect biodiversity by providing valuable insights into butterfly foraging behavior and the relationship between butterfly proboscis length and flower corolla tube length. Additionally, enhancing our understanding of pollination dynamics and ecological interactions is instrumental to conserving butterfly diversity and habitat.

4. Discussion

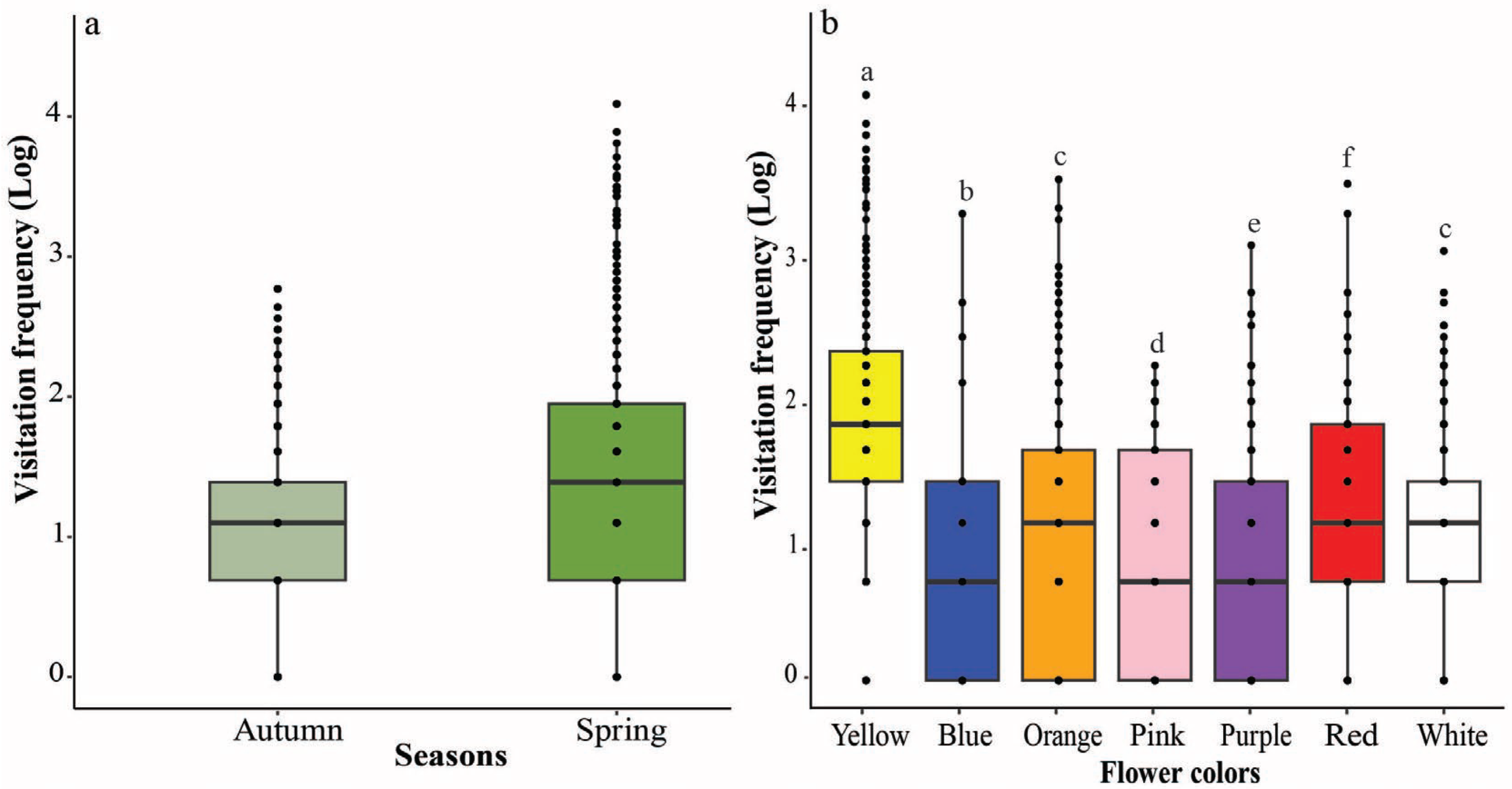

The study highlighted that the multiple plant characteristics, such as flower color, origin, and type, significantly influence butterfly visitation frequencies to the flowers. There was a significant difference between butterfly visitation in two different seasons, i.e., spring and autumn, in different flower colors. Butterflies visited yellow flowers more frequently, followed by white, orange, pink, purple, red, and blue flowers. This might be because butterflies prefer light-colored flowers more than dull-colored ones. Butterflies in Rupa Wetland of Nepal exhibited a significant inclination towards flowers with yellow, white, and purple, while they were less likely to visit pink flowers [

16]. Color is the most important visual signal that attracts butterflies during foraging [

17]. A study conducted in India suspected that butterflies visit yellow color more often, which might be attributed to the possibility that yellow flowers might have offered more nectar to visiting pollinators than other color flowers [

21]. Tiple et al. [

5] reported the frequency of butterflies’ visitation was found significantly higher in yellow, red, blue, and purple when compared to white and pink flowers. Blackiston et al. [

20] showed that monarch butterflies selected yellow flowers more frequently than blue flowers, with red being the least preferred color. Briscoe et al. [

38] also observed that there was an association between the color preferences of closely related butterfly species when foraging for nectar and indicated that color preference may be due to the phylogenetic traits of their color vision and its evolution may have played a significant role in shaping the foraging behavior of butterflies. In this study, we found that butterflies exhibited the lowest preference for blue flowers among the colors examined. This result contrasts with previous studies that identified a higher preference for blue flowers in certain butterfly species. For example, Swihart [

39] and Scherer and Kolb [

40] reported a preference for blue in heliconiid and satyrid butterflies. Additionally, research on the green-eyed white butterfly (

Leptophobia aripa) indicated a strong preference for red flowers over pink, white, and yellow ones [

41], making red the second least preferred color in our study. The variations in flower color preferences across different studies may be influenced by factors such as species-specific visual sensitivities to different colors [

17] and the relative abundance of various flower colors. In our study, the lower preference for blue flowers may be explained by their reduced abundance compared to other colors, while red flowers were the least abundant. Furthermore, our research evaluates cumulative foraging preferences across multiple butterfly species, whereas studies with differing results often focused on a single species or family of butterflies. The study revealed that butterflies prefer alien over native flowers, which might be related to the higher resource availability (nectar) or more compatible with the alien flowers’ floral characteristics. Bergerot et al. [

30] found that butterflies possessing long proboscises more frequently visited alien plants, as their flowers tend to be deeper than the native flowers. Additionally, alien flowers were taller and had larger floral diameters than their native flowers. The choice of native and alien plants was found to be strongly correlated with the length of the proboscis. Furthermore, butterflies are known to be rapid learners who prefer highly rewarding flowers over natural color preferences [

42]. Similarly, a high floral preference for butterflies’ visitation was found in herbs than shrubs which might be associated with the quality and quantity of the food produced by the different types of flowering plants. Tiple et al. [

5] investigated the visitation frequency of butterflies to flowers of diverse plant categories and showed that butterfly visitation frequency was higher to herbs than to shrubs. As butterflies often require frequent broods and need a constant supply of nectar from flowering plants. In this context, herbs and shrubs may play a crucial role by providing nectar more consistently than trees do. In rainy seasons butterflies obtain more floral nutrients from herbs and shrubs and mostly depend on trees during dry seasons [

43].

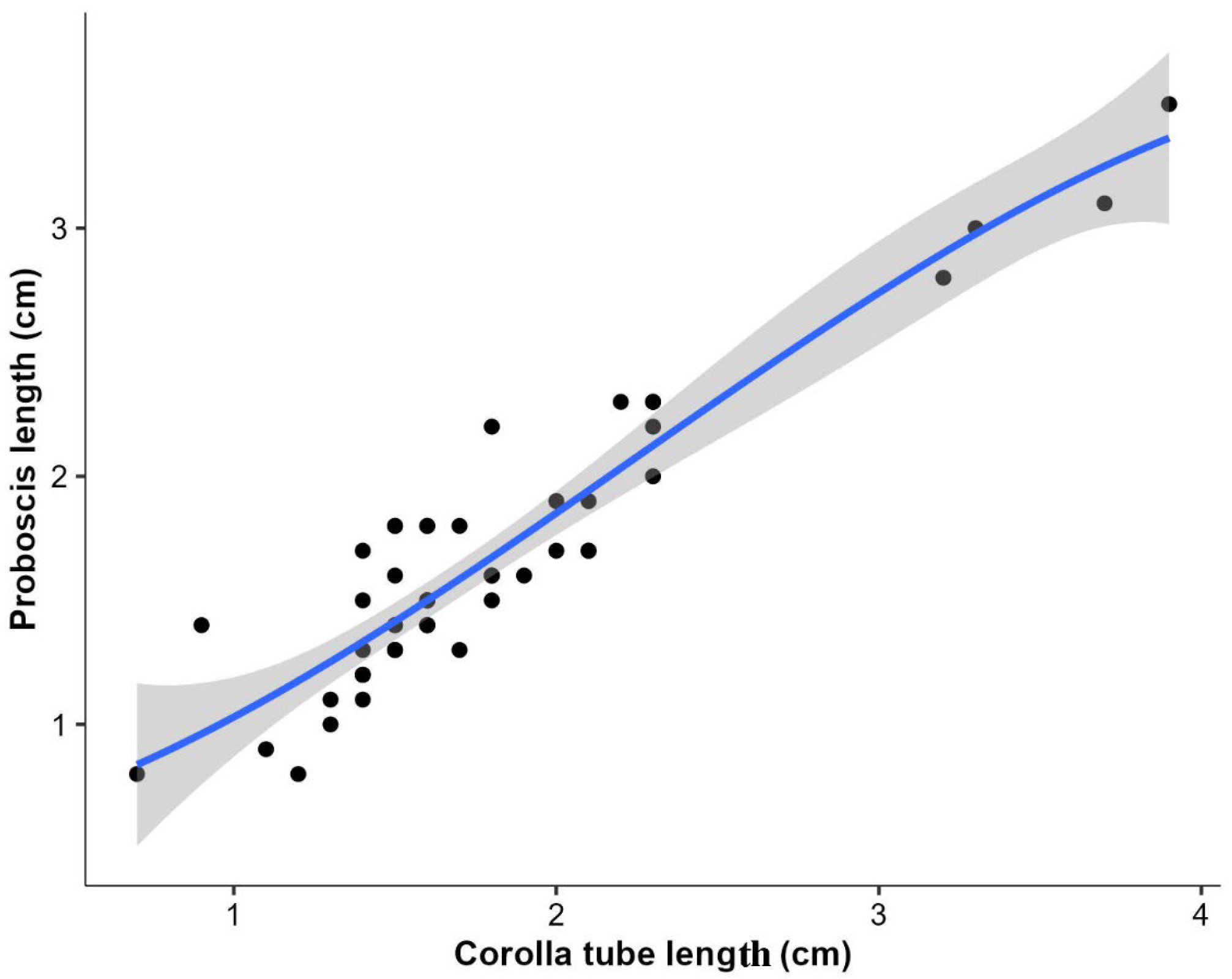

This study found that a significant association exists between the length of butterflies’ proboscises and the depth of flower corollas. In particular, butterflies with shorter proboscises generally prefer flowers with shorter corolla tubes, whereas those with longer proboscises are more likely to visit flowers with deeper corollas. Proboscis and corolla lengths were significantly associated with each other among butterflies in Rupa Wetland, Nepal [

16]. According to Corbet [

44], the depth of a flower’s corolla limits the consumption of nectar by the unsuitable butterfly species and stores nectar for those with proboscises of sufficient length. Consequently, a butterfly with a shorter proboscis is unable to access nectar from flowers with deep corollas. Ranta and Lundberg [

45] reported that in bumblebees, when proboscis length matched the depth of the flower’s corolla, the foraging efficiency was maximum. This suggests that bumblebees with longer proboscises are more efficient at accessing nectar from flowers with deeper and more diverse corollas. A similar correlation was observed between the proboscis length of clouded apollo (

Parnassius mnemosyne) butterflies and their flower visitation to flowers with deeper corollas [

46]. Coevolution between butterflies and flowers is the major factor that contributes to the association between corolla length and proboscis length [

47]. Another study reached the same conclusion that butterflies can only be able to feed from flowers whose corolla depth falls within their proboscis length range. Similarly, Tiple et al. [

31] studied butterflies at the family level and demonstrated that butterflies belonging to Papilionids more frequently fed on the flowers with deep corolla tubes in central India. Mertens et al. [

48] detected a positive relationship between the lengths of the proboscis of hesperoid butterflies and tubes of visited flowers in the tropical rainforests of Mount Cameroon. These associations between butterflies and plant traits enable us to understand the ecology of butterflies, and hence such knowledge could be applicable in managing botanical gardens with diverse floral plants and a higher diversity of pollinators such as butterflies.

This study provides valuable insights into butterfly floral preferences at the National Botanical Garden; however, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the observations were limited to just two seasons, which may restrict our understanding of year-round variations in butterfly visitation patterns. Second, because the study examined a multi-species butterfly population, the findings may be biased towards the most abundant species, potentially obscuring the distinct or contrasting floral preferences of rarer species. Third, we tested the floral preferences of butterflies and found that they favored alien flowers over native ones; however, we cannot conclude that the plants preferred by butterflies equally support their immature stages. Additionally, while we explored the relationship between butterfly proboscis length and corolla tube length, we did not account for other morphological or ecological factors that could influence these interactions. Future studies that include data from all seasons, focus on species-specific behaviors, and incorporate additional ecological variables would enhance our understanding of pollinator–plant interactions.