1. Introduction

There is little doubt that living and learning in and from a specific place can build an extensive constellation and depth of personal experiences. Local knowledge or traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is just one term that describes this combination of understanding, comprehension, traditions, and practices of many different local cultures and communities spanning generations worldwide [

1,

2]. Often, local conservation practices have cultural connections and showcase ecological or sustainable elements that reflect the values that specific local communities hold for their local areas [

3], including connections to nature that define how a community interacts with and within the world around them [

4].

As we face the ecological crises of today head-on, more scientists are acknowledging and turning to local community-based strategies and the conservation work of native communities and cultural groups to contribute innovative solutions. Scientists are more readily working with native communities to include TEK practices in addressing problems such as climate change [

5,

6,

7]. Australian bushfires have worsened over recent decades due to climate change, and the Australian local practice of preemptive firestick burning has been proven to be an effective management practice [

8], as have north-eastern Ghana farmers practice of reducing drought effects by planting native drought-resistant plants, among many other examples [

9]. Local community knowledge and experiences have proven essential in some exemplary cases to positively improve conservation outcomes at the local level [

6,

10].

TEK gives insights into the complex place-based relationships of human communities and our natural environments [

11,

12]. This knowledge is shared within families and between individuals through ceremonies and storytelling, at meetings and conference presentations, and by observing current ecological systems in practice, as some examples [

13,

14]. There are many well-known examples of traditional knowledge that have been the foundation of common practices such as hunting practices as a means of maintaining animal populations, traditional tools for hunting and plant management [

11], crop rotations to allow for nutrients and natural resources to be replenished while plants grow and mature over time, understanding species behavior and breeding habits so as to not deplete species over time, and studying weather patterns [

3].

These local practices can reflect both care for the land and interest in conserving resources. TEK can offer local conservation solutions and integrate the holistic views and practices of local communities into formal sciences [

15]. TEK is not always documented through the written word but is a complex combination of ideas and practices that are incorporated into the fabric of a community [

9,

11,

16] and can be shared with the wider public, including non-native audiences. It is clear that the interconnected aspects of community [

1,

17] and personal values [

18] are well-documented as a means of preserving the ecology of a place. As just one example, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Ilisagvik College incorporated this knowledge exchange by creating lessons with Inupiat Elders to share their place-based local knowledge in their climate change curriculum [

12].

Zoos and aquariums worldwide are beloved local institutions, attracting thousands of visitors annually and offering families and communities places connected with nature. These institutions are environmental education settings that establish connections or experiences with specific places where individuals can form bonds and thereby create a personal sense of place and cultivate personal identity [

19,

20]. As people create bonds with places in nature, this leads to the phenomenon of wanting to connect further [

21]. By experiencing unique moments with nature, people can foster positive associations with a place throughout their lives [

22]. Informal education settings like zoos and aquariums are in a unique position to create a sense of place while also focusing on educating and entertaining visitors. When visitors can create direct personal connections to animals and landscapes, they tend to seek out further connections and become inspired to engage in learning even more [

23]. This can result in conservation action from visitors, leading to further conservation synergies and formal and informal education opportunities.

Personal natural connections in settings like zoos can lead to conservation action. Zoos can utilize people’s natural curiosity about animals and their environments to educate and inspire them to want to connect further and make behavioral changes [

24]. Visitors can gain a connection with and garner sympathy for animals and the environment within zoos as they learn about the natural world and what is happening to it. With this empathy and knowledge, zoo visitors are more likely to make a behavioral change toward conservation action [

19,

25].

Nature connections are especially important in urban settings such as New York City where there is a lack of green spaces [

26]. Zoos in urban centers have become central to providing access to cultivating and appreciating nature by offering up-close experiences with animals and plants [

26]. Urban centers such as zoos can impact a wide variety of people of different ages, economic backgrounds, ethnicities, and genders [

27]. These cultural centers can positively impact people, bringing them education, connection, and community [

28]. Zoos are cultural centers that connect people to their environments and the world around them, with the intent of impacting social change and pro-environmental behavior [

23,

29]. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and other urban zoos have the ability and resources to partner with outside conservation organizations and participate in in situ conservation efforts [

27].

In addition, as cultural centers, zoos and aquariums often prioritize academic and formal science information as the main sources for visitors’ learning about animals, habitats, and relevant conservation issues [

6,

30,

31]. Zoos primarily use signage, animal programs, and webpages to provide visitors with more in-depth information with the goal of both entertainment and teaching [

19,

30]. TEK has great potential to harness the natural curiosity of visitors to teach conservation-based knowledge in unique and memorable ways while elevating local voices.

Although there is some recent work on the inclusion of TEK in zoo settings such as in zoo signage [

32], there is little research on the prevalence of TEK in these locations or how and where else TEK is being used specifically in zoo and aquarium settings [

31]. This study explores the exhibit signage, webpages, and animal-based educational programs of the five Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)-accredited institutions within the Wildlife Conservation Society (based in New York City) to assess the inclusion of TEK within a visitor’s experience. From this knowledge, we present recommendations with which zoos and aquariums can readily include TEK in current and future educational settings.

3. Results

A total of 64 specific zoo/aquarium content areas were assessed within the five AZA institutions including 46 exhibit signage reviews, 5 webpages, and 13 animal programs, the total number containing conservation information. We found that a total of 15% (

n = 7) contained any cultural or TEK information; these included 4 exhibit signs and 3 webpages, while no TEK elements were found in any animal programs reviewed (

Table 1).

Over 76% of Content Areas did not use TEK and did not acknowledge indigenous peoples, and 11% did not use TEK but acknowledged indigenous peoples. Eight percent used TEK but from an outsider’s perspective, and 5% used TEK in the cultural context. No areas employed education methods that used TEK in traditional ways.

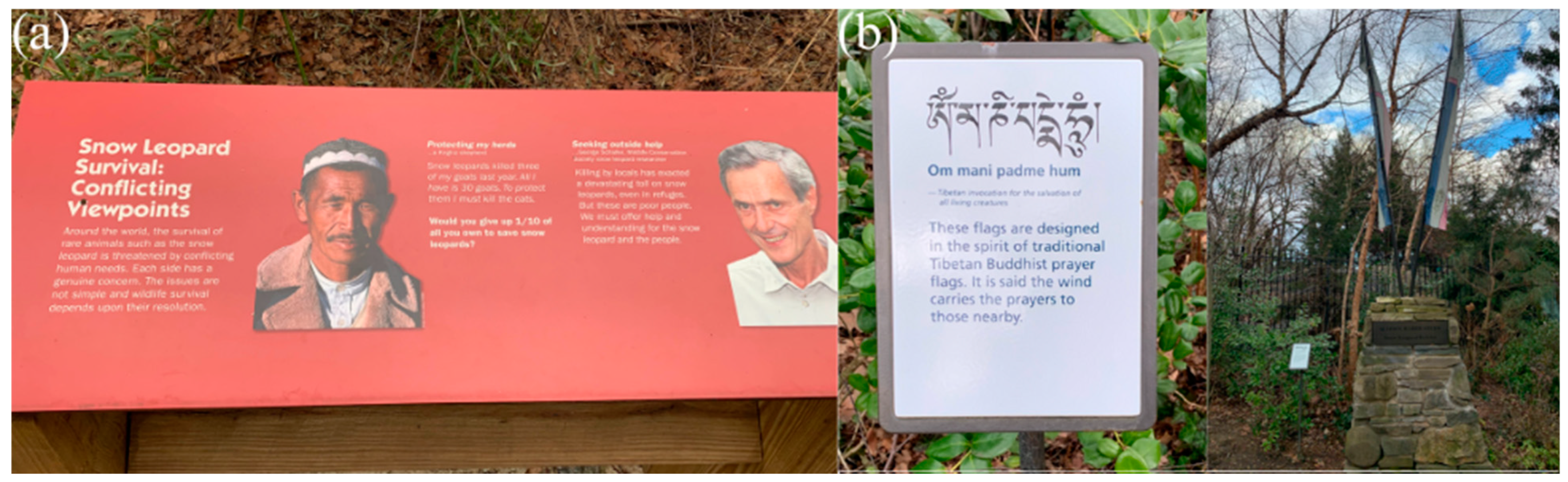

When cultural knowledge or TEK was included in exhibit signage or webpages, the information focused generally on spiritual, medicinal, or ecological practices. Of the four exhibit signs reviewed, one focused on TEK-related spiritual elements (i.e., Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags that symbolize care for all living creatures at Central Park Zoo) and included a cultural item, one offered a general statement on traditional medicine (i.e., brief mention of traditional medicines at the Bronx Zoo’s Tiger Mountain exhibit), and two briefly explained ecological/agricultural practices (e.g., mentions of agricultural practices in the Bronx Zoo’s Madagascar exhibit). Of the three webpages with TEK, one mentioned specific practices and how WCS has partnered with communities to include their TEK practices in WCS’s conservation work, and two pages spoke generally of TEK with no detail. No mention of TEK was included in any animal programs that were reviewed.

Cultural symbols were rarely used to convey conservation information. Most areas used a combination of audio or video and interactive elements, with all areas using image. However, there was a lack of cultural symbols or objects overall, as only one the areas reviewed showed a cultural symbol as an object (i.e., Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags that symbolize care for all living creatures at Central Park Zoo).

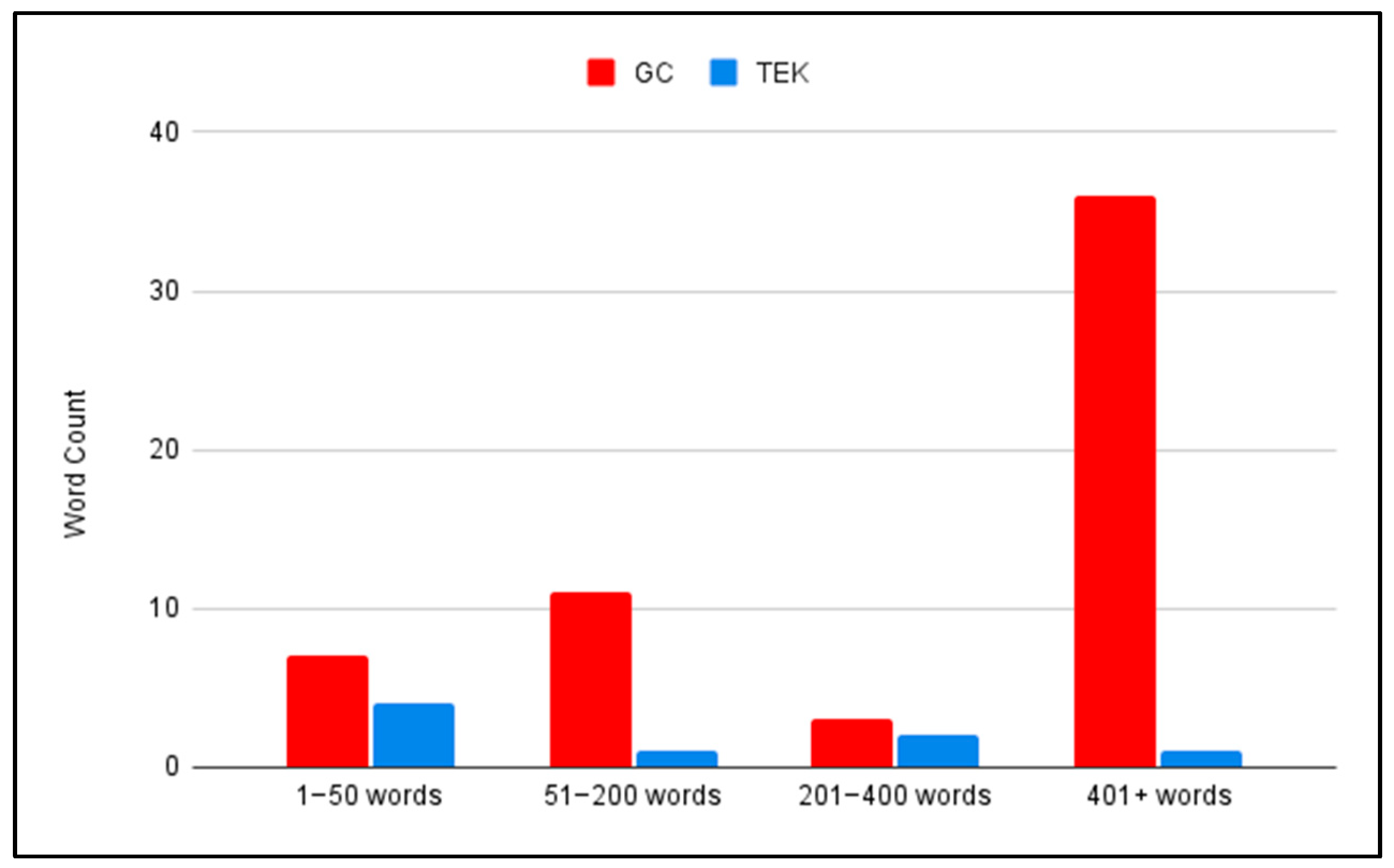

The word count for general conservation (GC) messaging was much higher than the word count for TEK-related text (

Figure 1). Of the 57 areas that used GC, 36% of signage used under 400 words, and 63% used over 400 words. For the seven areas that used TEK-related language, 86% were under 400 words with 50% of areas using less than 50 words. Only one of the seven areas that used TEK had over 400 words. With only 15% of total areas including TEK, the bulk of educational text included general conservation messaging. Signage with less than 50 words was often small text on a panel, and signage with over 400 words was often multi-panel signage.

Names of outside researchers were more likely to be found than specific or even general names of native experts or local communities. As depicted in exhibit signage or on zoo webpages, a total of 64 different people were shown, with 50% (n = 32) being outside researchers and 30% (n = 19) being “local or native people” in a general message without any specific names of individuals and communities depicted. Signage or webpages including native individuals’ names or indigenous community names totaled 13% (n = 8).

4. Discussion

Our results corroborate that TEK is significantly underutilized as compared with other conservation information messaging in the WCS’s zoos and aquarium. Only 15% of areas in this study contained TEK, yet general conservation information was prevalent throughout all the parks studied, with 63% of exhibits having longer word counts on this topic, which could be an indication there is an interest in educating about conservation. TEK messaging was rarely seen at all, and when present, the TEK messages were superficial in content. This could be seen as a lack of interest in TEK or local communities or, what is most likely, a missed opportunity by zoos to tell a richer story of the conservation work happening in a particular area by including storytelling elements, expanding cultural content, and including the role of local communities as key figures in conservation solutions.

It is important to note that TEK is not found at present in any animal programming offered at the locations included in this study. Many animal programs include storytelling elements and the use of animals that have significance to the locations and cultures they come from [

3,

30]. TEK often incorporates animals and their importance into their myths and stories, giving them cultural significance [

9]. These traditional ways of teaching are not only entertaining and engaging for youth, but have withstood the test of time by being passed down through multiple generations [

3,

16]. Myths and storytelling inspired by TEK could be enjoyable for all visitors and connect them further to the animals and the cultures from which they come [

32]. The Taronga Conservation Society of Australia has incorporated TEK into its animal programming [

37]. Programs such as ”Animals of the Dreaming Zoomobile” incorporate traditional music. By getting a more rounded view of the animals, conservation, and cultures, visitors could become more interested in returning to zoos or even taking on personal conservation action [

16,

30]. TEK stories can easily be incorporated into animal programming.

Zoos put significant effort into representing animals in their environments, yet there is little effort to talk about the people who are a part of these environments. General conservation information was prevalent in the parks, with 63% of exhibits having over 400 words regarding conservation, indicating there is an interest in educating about conservation. However, TEK messaging with over 400 words was only used once, and the average word count about TEK was less than 50 words. This are not enough words to authentically incorporate a community and its culture within the full cultural context.

Underrepresenting cultural groups and TEK minimizes the role of local communities that participate actively in efforts to protect their environments. Even with a low word count regarding TEK in the parks, many of the areas mentioned one individual or community very generally without the use of a specific person’s or community’s name. Additionally, in these instances, researchers from outside TEK organizations are named. This dichotomy of presentation can communicate to zoo visitors that outside researchers, often Western, are more important than the names of indigenous people. This presentation style does not allow visitors to have a further understanding of the many ways TEK groups invest in conservation and can trivialize or misappropriate a group’s culture [

5,

9]. The Bronx Zoo’s Himalayan Highlands’ exhibit signage (

Figure 2) depicts human–animal interactions and conflicts in the region. The sign depicts a WCS researcher by his specific name (George Schaffer), and the indigenous person who lived in the region and was daily impacted by the human–animal interactions is named on the sign as ”shepherd.” These signs can be misleading and over-emphasize some people over others simply by the presentation style. Zoo signage that accurately represents native cultures, languages, and perspectives can foster pride and recognition among native communities. This can help preserve and promote indigenous languages, traditions, and knowledge systems. Signage that leaves out these important local connections and people reinforces stereotypes or a Western-savior narrative [

6,

38,

39]. Inaccurate depictions of indigenous cultures can further erode trust between zoos and native communities and contribute to cultural appropriation, marginalization, and tokenism [

5]. To improve the sign at the Himalayan Highlands Exhibit, for example, the signage could be changed to accurately reflect all parties by working with local communities to ensure equal representation of outsider and local conservation roles.

Accurate presentations of local communities can prevent their marginalization while also sharing educational and engaging content for zoo guests [

40]. For instance, Central Park Zoo features Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags that symbolize care for all living creatures (

Figure 2). Signage like this incorporates accurate Buddhist traditions into zoo signage. Guests can connect with the animals and the zoo and understand the connection that many Tibetan people have with nature. This signage is presented with context and helps guests have a better understanding of this community and its relationship with the world around them.

Furthermore, we have identified several specific actions that zoos and aquariums can take to include cultural and TEK-inspired elements as a larger part of the visitor experience.

Zoos can incorporate TEK into existing signage. Cleveland Metropolitan Zoo has a wall dedicated to Native Americans in their Wolf Lodge exhibit. The wall does not include the names of specific nations. The exhibit depicts artifacts such as hunting gear, shoes, children’s toys, and other daily objects. Having exhibits like this indicates that zoos do have an interest in sharing the knowledge, stories, and cultures of native and indigenous communities. This is an opportunity to connect TEK to these exhibits and educate visitors on these communities and their land. Although this exhibit gives interesting information on Native American objects and their importance, additional depth and specifics could be added. For example, the names of the Seneca, Shawnee, Wyandot, and Miami tribes who originally inhabited and were forcibly removed from the land the city of Cleveland now occupies could be included [

41]. In addition to group names, zoos have the opportunity to highlight native communities’ unique connections to the land [

14,

32] which could include short stories and lessons to increase their relevance to visitors. Many informal institutions such as zoos and botanical gardens have created more interchangeable signages to allow a more agile approach. Signage could be switched out more often and show an ongoing series of cultural stories and TEK informational elements.

Zoos can co-create messaging to highlight the current work of indigenous community members and allow them to tell their own stories. Zoo webpages and on-site signage can include current TEK stories, news, and information to further highlight that local communities are currently working toward conservation solutions. The Henry Vilas Zoo in Wisconsin collaborated with the native Ho-Chunk people to incorporate stories and language into the signage of the North American Prairie exhibit. This area features interactive signage and QR codes that take visitors to a webpage to learn about Ho-Chuck culture and specific local knowledge of the animals of the region [

42]. The Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden is working collaboratively with the Myaamia (Miami) people to better represent the stories and species of the Ohio and Midwestern region as part of a new North America exhibit. Outside the U.S., the Auckland Zoo (AZ), New Zealand, also includes the native language of Māori in all exhibit signage and webpage text and teaches basic phrases in its animal programming [

43]. Specifically, AZ includes lessons about how to use local medical herbs and teaches through poems, myths, and storytelling. AZ hires Māori people bringing their culture directly into a zoo conservation setting [

44,

45]. By collaborating with local communities in a space that allows local indigenous cultures to share their own unique perspectives, zoos can spread TEK and amplify native voices to millions of zoo visitors.

Remind visitors that local communities are found globally. Many zoos work with international organizations that focus on in situ conservation globally and because of this, zoos have direct interactions with a diverse range of people, local experts, researchers, and cultures [

46], and this network of global partnerships is not fully reflected in zoo grounds [

27]. Visitors could engage with signage, videos, or interchangeable storyboards as opportunities to become more connected with global communities on a deeper level. Zoos can share that this cultural or TEK information is direct from local communities as a way to further elevate community voices. These global connections can be easy to make, as many zoos care for and conduct research about global species and can connect zoo visitors to conservation efforts on the local and global levels.

Zoos can foster further personal-natural connections. Primarily located in cities, zoos and aquariums work hard to enhance their natural habitats, many with large shade trees and beautiful flower paths on grounds. In some cases, large city parks and zoos serve as the primary tended natural areas with a diversity of plant species, insects, and bird life. Zoos have an opportunity to further inspire personal–natural connections for visitors by including TEK and other cultural elements. A detailed description of the vast blue skies and grasses of the Mongolian steppe can offer zoo visitors novel information about the local environments in which native species live. Next, signage could ask visitors to take a moment to notice the colors and plant species around them. A great hornbill (

Buceros bicornis) exhibit could offer a spot for visitors to sit and practice a mindful moment to mimic what the Buddhist researchers of the Thailand Hornbill Project might experience meditating in the forest, awaiting this showy bird species [

47]. There are countless ways to include up-close and personal opportunities for zoo visitors to engage more deeply with the natural world as a part of their day at the zoo.

Create a TEK-focused working group. AZA has different working groups that focus on zoo areas, such as zoo keeping, animal welfare, community conservation, and wildlife trafficking. Surprisingly, there is not yet an AZA working group that is focused on TEK or how this local information can be used in educational settings. AZA would benefit from sharing how TEK is being used and can be used within AZA-accredited zoos. With such a public presence, zoos could further elevate TEK knowledge and encourage other zoos within AZA to do the same.

Important conservation messages can be highlighted with TEK. Zoos already share conservation messaging, including information on community-based conservation projects, and many share the work of in-country partners in their signage [

30,

46]. Explicitly stating how conservation solutions are community-based and guided by TEK expertise can create awareness and further communicate to visitors the importance and necessity of TEK as a conservation practice. For example, signage including local stories of the Central American tapir (

Tapiris bairdii) research happening in Belize [

48] could include images of local Belizean art installations that are intended to help local communities know to slow down on major roads; this could help zoo visitors consider how their own driving speeds may impact local species.

Zoos can assess TEK and make goals for further inclusion. Although this pilot study demonstrates the underutilization of TEK in several New York area zoos and aquariums, this work is only the beginning. Future research could collect data on many more informal learning institutions and focus on animal programming. Home learning groups like homeschool teachers could be interviewed as well to see what TEK knowledge is interesting to and sticks with visitors. This study was conducted at the five zoo and aquarium institutions within the Wildlife Conservation Society, and results could be different if conducted in other areas of the country with strong native community connections or within different countries where local groups are more deeply woven into the fabric of the countries. In addition, the knowledge and skills gained by exploring a specific culture may not be able to be generalized, and conversations with local communities can help zoos unpack how to further cultural connections with zoo audiences.