Oro-Facial Angioedema: An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

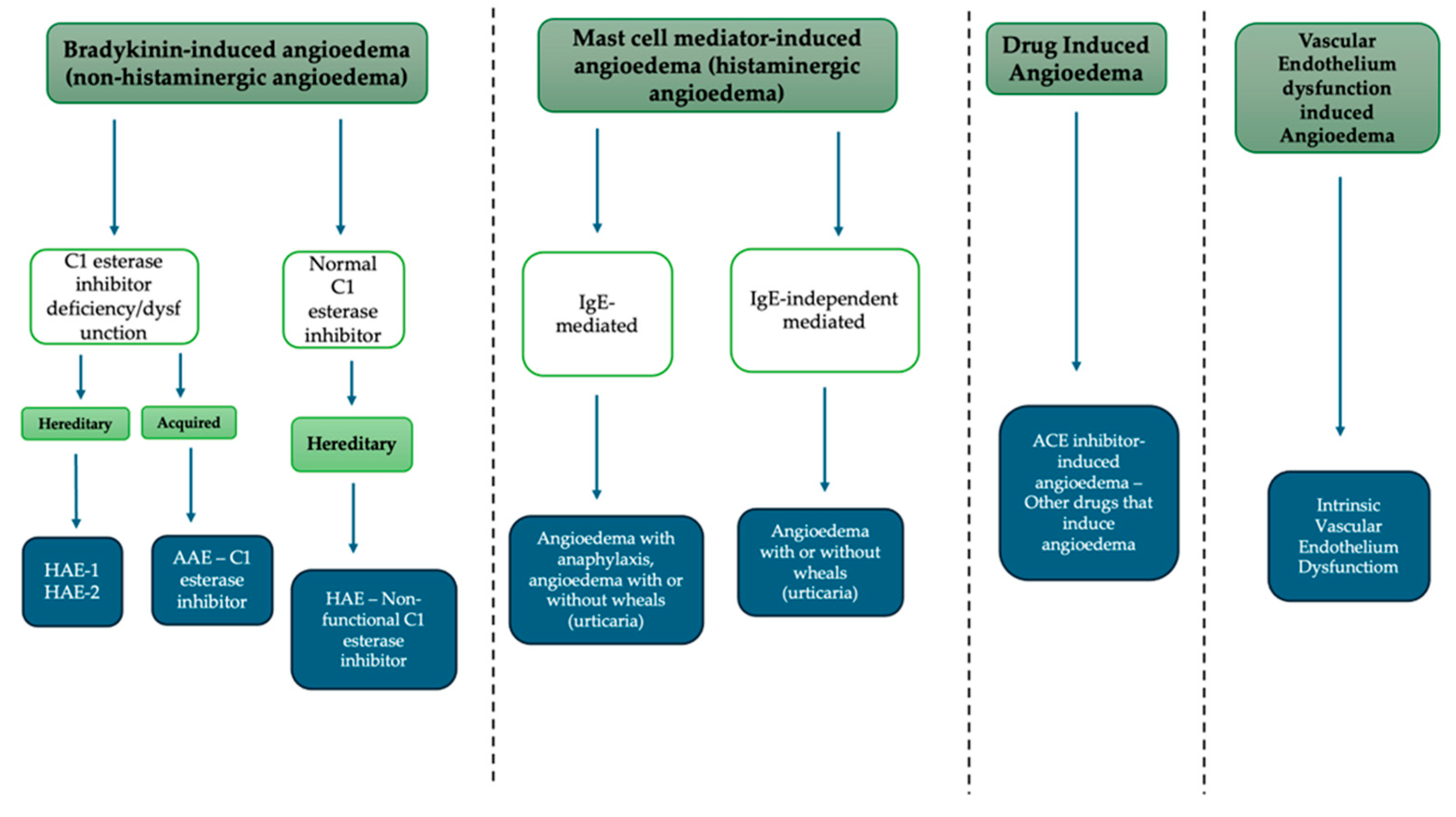

- Bradykinin-mediated angioedema;

- Hereditary angioedema due to C1-INH deficiency or dysfunction;

- Acquired angioedema due to C1-INH deficiency;

- Hereditary angioedema with normal C1-INH;

- Acquired angioedema;

- Mast cell mediator-induced angioedema;

- IgE-mediated angioedema;

- Non-IgE mediated angioedema.

3. Bradykinin-Mediated Angioedema

3.1. Hereditary Angioedema Due to C1-INH Deficiency or Dysfunction (HAE Types I and II)

3.2. Acquired Angioedema Due to C1-INH Deficiency (AAE)

3.3. Hereditary Angioedema with Normal C1-INH (HAE-nC1INH)

4. Drug-Induced Angioedema

5. Mast Cell Mediator-Induced Angioedema (Histaminergic Angioedema)

5.1. IgE-Mediated: Angioedema with Anaphylaxis, Angioedema with or Without Wheals (Urticaria)

5.2. IgE-Independently Mediated: Angioedema with or Without Wheals (Urticaria)

6. Vascular Endothelium Dysfunction-Induced Angioedema

7. Oro-Facial Angioedema: Differential Diagnosis

8. Dental Practice Implications

- Tooth extractions: as with other surgical procedures, they are the most frequently associated with AE. Local tissue damage activates the complement cascade, in particular the contact pathway, which promotes increased bradykinin production [62]. In patients with C1-INH deficiency or dysfunctional C1-INH, this process becomes uncontrolled. Bradykinin binds to the B2 receptor, causing vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, leading to AE [20].

- Allergic reactions to local anesthetics or dental materials such as nickel, resins, latex, or root canal irrigants (NaOCl), although rare, can manifest as AE with urticaria or, in severe cases, with anaphylaxis [63]. These type I (IgE-mediated) or type IV (cell-mediated) allergic reactions provoke mast cell degranulation and the release of histamine and other mediators, resulting in rapidly developing and potentially dangerous AE [20,63,64,65].

- Preoperative or “dental chair” anxiety may activate neuroendocrine mechanisms that facilitate the development of AE, particularly in patients with HAE [66]. In these cases, the use of nitrous oxide (N2O) as a sedative has been proposed to reduce anxiety during dental procedures, thereby helping to prevent AE attacks [67].

- Use of ACE inhibitors, which prevent bradykinin degradation, favoring its accumulation and leading to increased vascular permeability and subsequent AE [38]. In dentistry, a patient on chronic therapy may develop AE even in the absence of trauma or allergens. In such cases, treatment with antihistamines or corticosteroids is often ineffective [9,37,38].

9. Clinical Recommendation

10. Advances and Research Directions

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lima, H.; Zheng, J.; Wong, D.; Waserman, S.; Sussman, G.L. Pathophysiology of bradykinin and histamine mediated angioedema. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1263432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, G.A.; Boot, M.; Lathif, A. Quincke’s disease: An unusual pathology. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 2023, rjad085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, F.; Attermann, J.; Linneberg, A. Epidemiology of Non-hereditary Angioedema. Acta Derm. Venerol. 2012, 92, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Magerl, M.; Ansotegui, I.; Aygören-Pürsün, E.; Betschel, S.; Bork, K.; Bowen, T.; Balle Boysen, H.; Farkas, H.; Grumach, A.S.; et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema—The 2017 revision and update. Allergy 2018, 73, 1575–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch, S.A.; Rundle, A.G.; Neugut, A.I.; Freedberg, D.E. Worldwide Prevalence of Hereditary Angioedema: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 186, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanichelli, A.; Arcoleo, F.; Barca, M.; Borrelli, P.; Bova, M.; Cancian, M.; Cicardi, M.; Cillari, E.; De Carolis, C.; De Pasquale, T.; et al. A nationwide survey of hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency in Italy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, K.; Machnig, T.; Wulff, K.; Witzke, G.; Prusty, S.; Hardt, J. Clinical features of genetically characterized types of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, P.F.K.; Coulter, T.; El-Shanawany, T.; Garcez, T.; Hackett, S.; Jain, R.; Kiani-Alikhan, S.; Manson, A.; Noorani, S.; Stroud, C.; et al. A National Survey of Hereditary Angioedema and Acquired C1 Inhibitor Deficiency in the United Kingdom. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 2476–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerji, A.; Blumenthal, K.G.; Lai, K.H.; Zhou, L. Epidemiology of ACE Inhibitor Angioedema Utilizing a Large Electronic Health Record. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pr. 2017, 5, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, G.N.; Truong, T.M.; Chakraborty, A.; Rao, B.; Monteleone, C. Tranexamic acid for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–induced angioedema. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2023, 11, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J.A.; Cremonesi, P.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Hollingsworth, J. Angioedema in the emergency department: A practical guide to differential diagnosis and management. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorio, S.; Rivolta, F.; Tedeschi, A.; Manzotti, G.; Piantanida, M.; Marra, A.M.; Cappiello, F.; Yacoub, M.R.; Nannipieri, S.; Maffeis, L.; et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of chronic histaminergic angioedema and chronic urticaria with angioedema, a multicenter Italian experience. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Division of Immunology-Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Ege University School of Medicine, Izmir, Turkey; Gulbahar, O. Angioedema without wheals: A clinical update. Balk. Med. J. 2021, 38, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, P.K.; Fomina, D.; Kocaturk, E. Chronic inducible urticaria: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. IJSA Indian J. Skin Allergy 2022, 1, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmesa, A.; Zakiyah, N.; Insani, W.N. Clinical Presentations and Characteristics of NSAIDs Hypersensitivity in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Indonesia: A Case Series. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2025, 18, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magen, E.; Leibovich, I.; Magen, I.; Merzon, E.; Green, I.; Golan-Cohen, A.; Vinker, S.; Israel, A. Comorbidity Profile of Chronic Mast Cell–Mediated Angioedema Versus Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Vivolo Aun, M.; Giavina-Bianchi, M.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Camara Agondi, R.; Motta, A.A.; Kalil, J. Hereditary angioedema classification: Expanding knowledge by genotyping and endotyping. World Allergy Organ. J. 2024, 17, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, M.C.; Banerji, A. Angioedema without urticaria: Diagnosis and management. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2025, 46, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumach, A.S.; Riedl, M.A.; Cheng, L.; Jain, S.; Nova Estepan, D.; Zanichelli, A. Hereditary angioedema diagnosis: Reflecting on the past, envisioning the future. World Allergy Organ. J. 2025, 18, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutunaru, C.V.; Ică, O.M.; Mitroi, G.G.; Neagoe, C.D.; Mitroi, G.F.; Orzan, O.A.; Bălăceanu-Gurău, B.; Ianoși, S.L. Unveiling the Complexities of Hereditary Angioedema. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, J.M.; Poarch, K.; Hughes, S. Recognition and Differential Diagnosis of Hereditary Angioedema in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 60, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, T.J.; Bernstein, J.A.; Farkas, H.; Bouillet, L.; Boccon-Gibod, I. Diagnosis and Treatment of Bradykinin-Mediated Angioedema: Outcomes from an Angioedema Expert Consensus Meeting. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 165, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, P.J.; Farkas, H.; Banerji, A.; Lumry, W.R.; Longhurst, H.J.; Sexton, D.J.; Riedl, M.A. Lanadelumab for the Prophylactic Treatment of Hereditary Angioedema with C1 Inhibitor Deficiency: A Review of Preclinical and Phase I Studies. BioDrugs 2019, 33, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolinska, S.; Antolín-Amérigo, D.; Popescu, F.-D. Bradykinin Metabolism and Drug-Induced Angioedema. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, T.; Pürsün, E.A.; Bork, K.; Bowen, T.; Boysen, H.; Farkas, H.; Grumach, A.; Katelaris, C.H.; Lockey, R.; Longhurst, H.; et al. WAO Guideline for the Management of Hereditary Angioedema. World Allergy Organ. J. 2012, 5, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santacroce, R.; D’Andrea, G.; Maffione, A.B.; Margaglione, M.; d’Apolito, M. The Genetics of Hereditary Angioedema: A Review. JCM J. Clin. 2021, 10, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanichelli, A.; Magerl, M.; Longhurst, H.; Fabien, V.; Maurer, M. Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency: Delay in diagnosis in Europe. All. Asth Clin. Immun. 2013, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraw, B.L.; Bork, K.; Bouillet, L.; Christiansen, S.C.; Farkas, H.; Germenis, A.E.; Grumach, A.S.; Kaplan, A.; López-Lera, A.; Magerl, M.; et al. Hereditary Angioedema with Normal C1 Inhibitor: An Updated International Consensus Paper on Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Clin. Rev. Allerg. Immunol. 2025, 68, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsiou, S.; Zamanakou, M.; Loules, G.; Psarros, F.; Parsopoulou, F.; Csuka, D.; Valerieva, A.; Staevska, M.; Porebski, G.; Obtulowicz, K.; et al. A novel deep intronic SERPING1 variant as a cause of hereditary angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency. Allergol. Int. 2020, 69, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelli, R.; Zanichelli, A.; Cicardi, M.; Cugno, M. Acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency and lymphoproliferative disorders: A tight relationship. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2013, 87, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicardi, M.; Zanichelli, A. Acquired angioedema. All. Asth Clin. Immun. 2010, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, G.; Edgar, D.; Trinder, J. Angioedema of the Tongue Due to Acquired C1 Esterase Inhibitor Deficiency. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2003, 31, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeza, M.L.; González-Quevedo, T.; Caballero, T.; Guilarte, M.; Lleonart, R.; Varela, S.; Castro, M.; Díaz, C.; Escudero, E.; García, M.G.; et al. Angioedema Due to Acquired Deficiency of C1-Inhibitor: A Cohort Study in Spain and a Comparison With Other Series. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, K.; Staubach-Renz, P.; Hardt, J. Angioedema due to acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: Spectrum and treatment with C1-inhibitor concentrate. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lange, M.; Petersen, R.S.; Fijen, L.M.; Cohn, D.M. Long-term prophylactic treatment with deucrictibant for angioedema due to acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 156, S0091674925008899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magerl, M.; Germenis, A.E.; Maas, C.; Maurer, M. Hereditary Angioedema with Normal C1 Inhibitor. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2017, 37, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostis, W.J.; Shetty, M.; Chowdhury, Y.S.; Kostis, J.B. ACE Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema: A Review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montinaro, V.; Cicardi, M. ACE inhibitor-mediated angioedema. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 78, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepelley, M.; Khouri, C.; Lacroix, C.; Bouillet, L. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor–induced angioedema: A disproportionality analysis of the WHO pharmacovigilance database. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 2406–2408.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanani, A.; Betschel, S.D.; Warrington, R. Urticaria and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, F.E.R.; Ardusso, L.R.F.; Bilò, M.B.; El-Gamal, Y.M.; Ledford, D.K.; Ring, J.; Sanchez-Borges, M.; Senna, G.E.; Sheikh, A.; Thong, B.Y. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines: Summary. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 587–593.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, M.S.; Wallace, D.V.; Golden, D.B.K.; Oppenheimer, J.; Bernstein, J.A.; Campbell, R.L.; Dinakar, C.; Ellis, A.; Greenhawt, M.; Khan, D.A.; et al. Anaphylaxis—A 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1082–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, P.; Nicklas, R.A.; Randolph, C.; Oppenheimer, J.; Bernstein, D.; Bernstein, J.; Ellis, A.; Golden, D.B.K.; Greenberger, P.; Kemp, S.; et al. Anaphylaxis—A practice parameter update 2015. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 115, 341–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuberbier, T.; Aberer, W.; Asero, R.; Abdul Latiff, A.H.; Baker, D.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Bernstein, J.A.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Brzoza, Z.; Buense Bedrikow, R.; et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy 2018, 73, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M.L.; Asero, R.; Bavbek, S.; Blanca, M.; Blanca-Lopez, N.; Bochenek, G.; Brockow, K.; Campo, P.; Celik, G.; Cernadas, J.; et al. Classification and practical approach to the diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Allergy 2013, 68, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, M.; Rosén, K.; Hsieh, H.-J.; Saini, S.; Grattan, C.; Gimenéz-Arnau, A.; Agarwal, S.; Doyle, R.; Canvin, J.; Kaplan, A.; et al. Omalizumab for the Treatment of Chronic Idiopathic or Spontaneous Urticaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerter, J.E.; Malkin, B.D. Odontogenic Orofacial Space Infections. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589648/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Vasanth, S.; Chandran, S.; Pandyan, D.A.; Gnanam, P.; Djearamane, S.; Wong, L.S.; Selvaraj, S. Case Report: Ludwig’s angina-“The Dangerous Space”. F1000Res 2024, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzi, M.; Messina, S.; De Falco, D.; Lucchese, A.; Romano, A.; Di Stasio, D.; Milillo, L.; De Benedittis, M.; Petruzzi, M. Dental abscesses and phlegmons: A brief review. Eur. J. Musculoskelet. Diseases 2022, 11, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, A.A.; Baker, K.S.; Gould, E.S.; Gupta, R. Necrotizing Fasciitis and Its Mimics: What Radiologists Need to Know. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, W.A.; Droz, N.C.; Wimalawansa, S.M.; Mancho, S.N.; Bernstein, J.M. It’s Not Always What It Seems: Necrotizing Fasciitis Mimicking Angioedema. Skinmed 2016, 14, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inal, A.; Ufuk Altintas, D.; Korkmaz Güvenmez, H.; Yilmaz, M.; Güneşer Kendirli, S. Life-threatening facial edema due to pine caterpillar mimicking an allergic event. Allergol. Et Immunopathol. 2006, 34, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, O.C.; Giger, R.; Alwagdani, A.; Aldabal, N.; Stenzinger, A.; Heimgartner, S.; Nisa, L.; Borner, U. Primary neoplasms of the parapharyngeal space: Diagnostic and therapeutic pearls and pitfalls. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 278, 4933–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluswamy, S.; Poondiyar Sirajuddin, S.H.; Padmanabhan, P.P. Cystic Myoepithelioma of Parapharyngeal Space. Indian. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2019, 71, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starmer, H.; Cherry, M.G.; Patterson, J.; Young, B.; Fleming, J. Assessment of Measures of Head and Neck Lymphedema Following Head and Neck Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2023, 21, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, C.R.; van der Molen, L.; Lindhout, J.E.; Bragante, K.; Navran, A.; van den Brekel, M.W.M.; Stuiver, M.M. Lymphedema and Trismus after Head and Neck Cancer, and the Impact on Body Image and Quality of Life. Cancers 2024, 16, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Falco, D.; Di Stasio, D.; Lauritano, D.; Lucchese, A.; Petruzzi, M. Orofacial Lymphedema in Phelan–McDermid Syndrome: A Case of Hemifacial Involvement and a Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.T.; Arioka, M.; Kleinman, S.H.; Gernez, Y. Masqueraders of angioedema after a dental procedure. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi, G.; Sardella, A.; Bez, C.; Demarosi, F.; Cicardi, M.; Carrassi, A. Dental experience and self-perceived dental care needs of patients with angioedema. Spec. Care Dent. 2001, 21, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi-Schumacher, M.; Shah, S.J.; Craig, T.; Goyal, N. Clinical manifestations of hereditary angioedema and a systematic review of treatment options. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2021, 6, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulthanan, K.; Jiamton, S.; Boochangkool, K.; Jongjarearnprasert, K. Angioedema: Clinical and Etiological Aspects. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2007, 2007, 026438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerji, A. Hereditary angioedema: Classification, pathogenesis, and diagnosis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011, 32, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speca, S.J.; Boynes, S.G.; Cuddy, M.A. Allergic Reactions to Local Anesthetic Formulations. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 54, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhole, M.V.; Manson, A.L.; Seneviratne, S.L.; Misbah, S.A. IgE-mediated allergy to local anaesthetics: Separating fact from perception: A UK perspective. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 108, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contaldo, M.; Di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Fiori, F.; Della Vella, F.; Rupe, C.; Lajolo, C.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A. Oral Candidiasis and Novel Therapeutic Strategies: Antifungals, Phytotherapy, Probiotics, and Photodynamic Therapy. Curr. Drug Delivery 2023, 20, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aygören-Pürsün, E.; Bygum, A.; Beusterien, K.; Hautamaki, E.; Sisic, Z.; Wait, S.; Boysen, H.B.; Caballero, T. Socioeconomic burden of hereditary angioedema: Results from the hereditary angioedema burden of illness study in Europe. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, B.; Katz, J.; Zilburg, I.; Shemer, J. Response to nitrous-oxide and oxygen among dental phobic patients. Int. Dent. J. 1998, 48, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.H.; Craig, T.J. Perioperative management for patients with hereditary angioedema. Allergy Rhinol. 2015, 6, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado-Palomo, J.; Muñoz-Caro, J.M.; López-Serrano, M.C.; Prior, N.; Cabañas, R.; Pedrosa, M.; Burgueño, M.; Caballero, T. Management of dental-oral procedures in patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, R.; Tobias, J.D. Perioperative care of a patient with hereditary angioedema. Pediatr. Anesth. Crit. Care J.-PACCJ 2014, 2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokmen, N.M.; Gumusburun, R.; Camyar, A.; Ozgul, S.; Ozısık, M.; Turk, T.; Sin, A.Z. The determinants of angioedema attacks related to dental and gingival procedures in hereditary angioedema patients. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Franco, R.; Miranda, M.; Casella, S.; D’Amico, C.; Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G. The role of anxiety in patients with hereditary angioedema during oral treatment: A narrative review. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1257703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerji, A.; Busse, P.; Shennak, M.; Lumry, W.; Davis-Lorton, M.; Wedner, H.J.; Jacobs, J.; Baker, J.; Bernstein, J.A.; Lockey, R.; et al. Inhibiting Plasma Kallikrein for Hereditary Angioedema Prophylaxis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Marier, J.-F.; Kassir, N.; Chang, C.; Martin, P. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Exposure-Response of Lanadelumab for Hereditary Angioedema. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 13, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loules, G.; Parsopoulou, F.; Zamanakou, M.; Csuka, D.; Bova, M.; González-Quevedo, T.; Psarros, F.; Porebski, G.; Speletas, M.; Firinu, D.; et al. Deciphering the Genetics of Primary Angioedema with Normal Levels of C1 Inhibitor. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerji, A.; Riedl, M.A.; Bernstein, J.A.; Cicardi, M.; Longhurst, H.J.; Zuraw, B.L.; Busse, P.J.; Anderson, J.; Magerl, M.; Martinez-Saguer, I.; et al. Effect of Lanadelumab Compared With Placebo on Prevention of Hereditary Angioedema Attacks: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshef, A.; Buttgereit, T.; Betschel, S.D.; Caballero, T.; Farkas, H.; Grumach, A.S.; Hide, M.; Jindal, A.K.; Longhurst, H.; Peter, J.; et al. Definition, acronyms, nomenclature, and classification of angioedema (DANCE): AAAAI, ACAAI, ACARE, and APAAACI DANCE consensus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 398–411.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Angioedema | Prevalence/Incidence | Sex Distribution | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hereditary Angioedema (HAE-1/2, C1-INH deficiency/dysfunction) | Global: 1.2/100,000 [5] Italy: 1:64,935 [6] UK: ≥1:59,000 [8] | M/F are equally affected [5] | Rare hereditary disease [5] |

| HAE with normal C1-INH (HAE-nC1INH) | Rare [7] | 80–90% female [7] | Estrogen-dependent symptoms [7] |

| Acquired Angioedema due to C1-INH deficiency (AAE) | 1:100,000–1:734,000 [8] | Similar M/F distribution [8] | Onset > 40 years, often associated with lymphoproliferative disorders or anti-C1-INH autoantibodies [8] |

| ACE inhibitor–induced Angioedema (ACEi-AE) | 0.1–0.7% among treated patients [9] | More frequent in women and Black individuals [10] | Accounts for 20–40% of emergency visits for angioedema [9,10] |

| Idiopathic/non-urticarial | Up to one-third of cases [4] | Slight female predominance (~55–60%) [4] | Unclear origin, not associated with urticaria [4] |

| IgE- mediated AE | 25% U.S. Patients [11] | Female predominance [12] | Rapid-onset, non-pitting, localized swelling of the lips, eyelids, face, tongue, or oropharynx—sometimes hands, feet, or genitals—often accompanied by itchy wheals when part of urticaria [13] |

| IgE-independent mediated AE | 0.5% Physical Urticaria 0.5–1.9% [14] NSAID-induced [15] | Female predominance [14] | Less predictable relationship with triggers, a predominantly cutaneous and benign but chronic–recurrent course without life-threatening systemic symptoms in most patients. Episodes typically last < 24–48 h and respond well to high-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines [16] |

| Vascular Endothelium Dysfunction-Induced AE | <1:1,000,000 [17] | M/F are equally affected [17] | Onset occurs in adolescence or early adulthood, with AE attacks involving the skin (especially face and limbs), tongue, upper airways, and sometimes the abdomen, with a risk of laryngeal involvement similar to other forms of HAE [17] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Falco, D.; Misceo, D.; Carretta, G.; Gioco, G.; Lajolo, C.; Petruzzi, M. Oro-Facial Angioedema: An Overview. Immuno 2025, 5, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno5040061

De Falco D, Misceo D, Carretta G, Gioco G, Lajolo C, Petruzzi M. Oro-Facial Angioedema: An Overview. Immuno. 2025; 5(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno5040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Falco, Domenico, Diego Misceo, Giuseppe Carretta, Gioele Gioco, Carlo Lajolo, and Massimo Petruzzi. 2025. "Oro-Facial Angioedema: An Overview" Immuno 5, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno5040061

APA StyleDe Falco, D., Misceo, D., Carretta, G., Gioco, G., Lajolo, C., & Petruzzi, M. (2025). Oro-Facial Angioedema: An Overview. Immuno, 5(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno5040061