Targeted Physical Rehabilitation for Physical Function Decline in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review

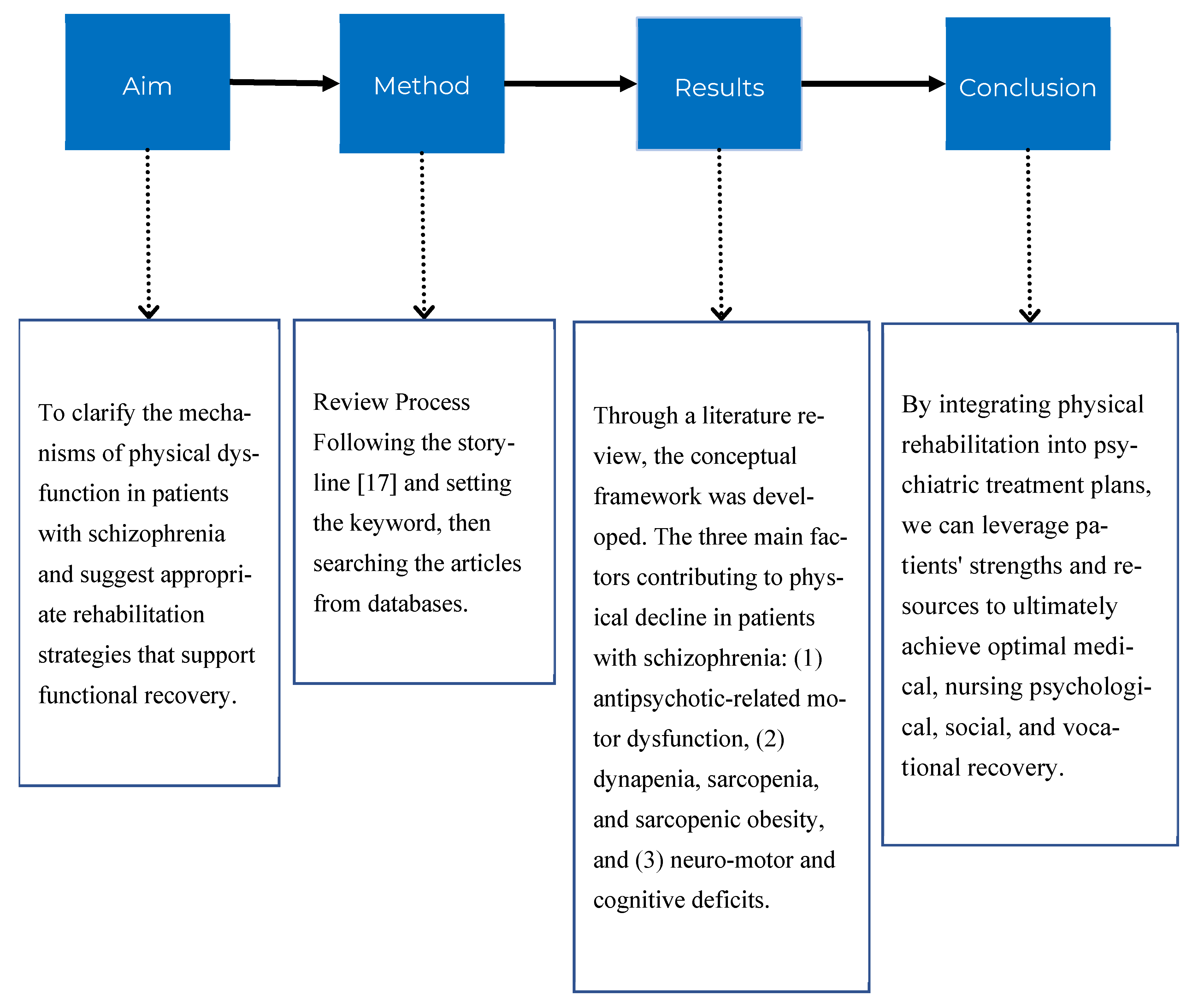

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

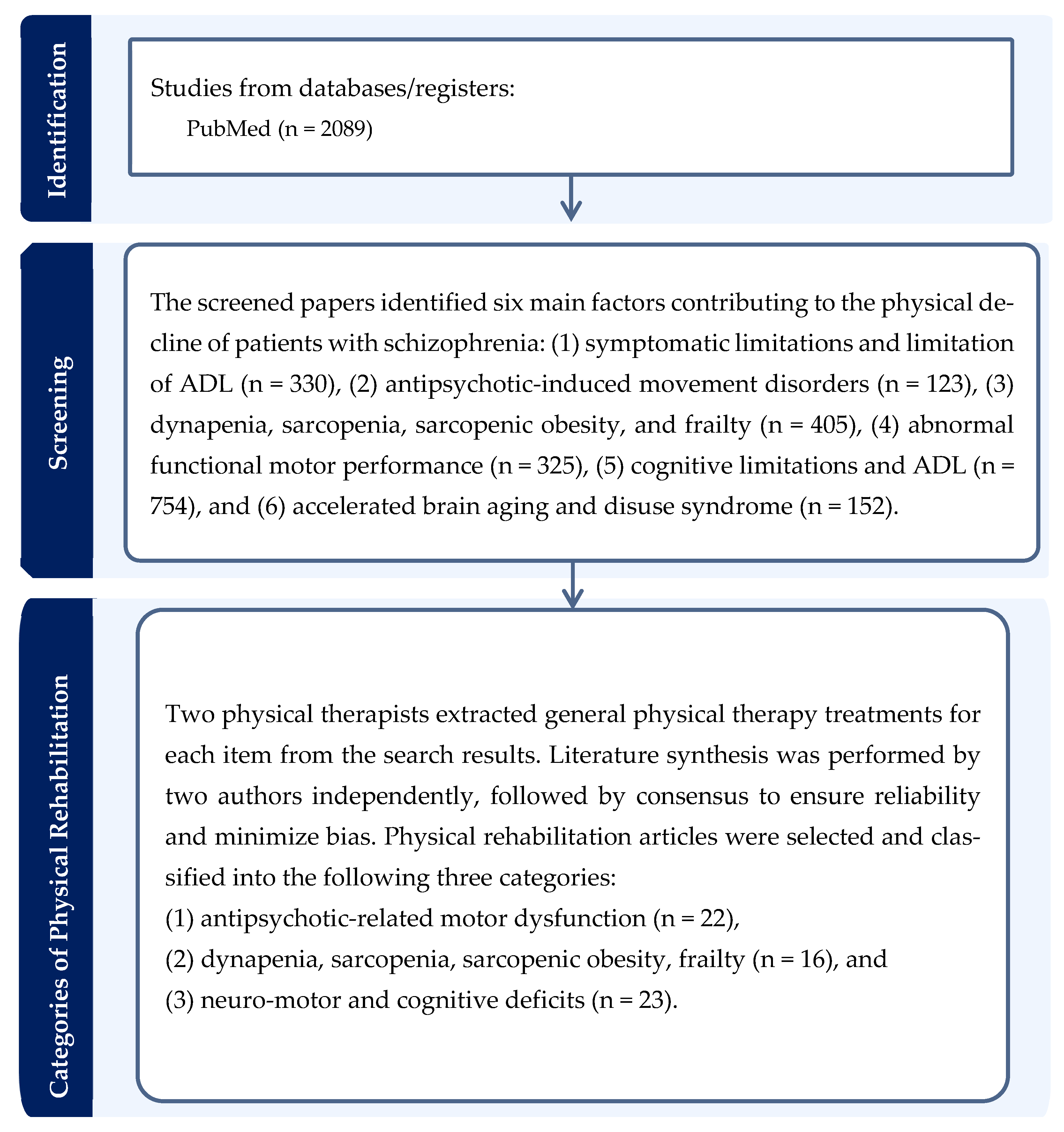

1.2. Literature Review to Develop a Conceptual Framework for Physical Rehabilitation

1.2.1. Search Strategy

1.2.2. Literature Review to Develop a Conceptual Framework

1.2.3. Symptomatic Limitations and ADL Restrictions

1.2.4. Antipsychotic-Induced Movement Disorders

1.2.5. Dynapenia, Sarcopenia, Sarcopenic Obesity, and Frailty

1.2.6. Abnormal Functional Motor Performance

1.2.7. Cognitive Limitations and ADL

1.2.8. Accelerated Brain Aging and Disuse Syndrome

1.3. Aim

2. Physical Rehabilitation for Antipsychotic-Related Motor Dysfunction

2.1. Targeted Interventions and Their Rationale

| Rehabilitation Approach | Rationale & Intervention | Key Characteristics of Schizophrenia | Comparative Insight | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility enhancement | Strength training to counteract drug-induced muscle weakness and improve functional mobility. | Antipsychotic-induced Parkinsonism and metabolic syndrome contribute to muscle weakness and altered gait patterns. | Although similar to sarcopenia in older adults, the etiology is distinct, emphasizing the need to address medication side effects. | [14,60,61] |

| Balance and postural control exercises to prevent falls. | Extrapyramidal symptoms and cognitive deficits impair balance and increase fall risk. | Unlike typical aging, fall risk is directly associated with medication-induced motor symptoms, requiring a specific focus on these side effects. | [64,65,66] | |

| Flexibility & Range of Motion | Stretching routines to maintain joint mobility and reduce stiffness. | Drug-induced Parkinsonism causes muscle rigidity and stiffness, limiting joint range of motion. | This approach is crucial for mitigating drug side effects, a factor less prominent in non-medication-related mobility decline. | [61,62,63,64] |

| Balance & Stability Training | Core strengthening and dynamic balance activities. | Impaired proprioception and trunk instability are common due to motor symptoms. | The focus on compensatory movement patterns is a unique aspect not always emphasized in other populations. | [65,66] |

| Dual-task and visual–vestibular training to improve adaptability. | Cognitive deficits and attentional impairments are prominent. | This approach integrates cognitive and motor tasks, directly addressing the dual impairment often seen in schizophrenia, which is a key differentiator from other single-domain conditions. | [67,68,69,70] | |

| Individualized Assessment | Using objective tools like Timed Up and Go and the Functional Reach Test. | Objective assessments are vital to measure subtle changes in motor function influenced by medication and symptoms. | The need for ongoing, sensitive monitoring is critical due to fluctuations in medication dose and symptom severity, making it a more dynamic assessment than in stable chronic conditions. | [32,71,72,73,74] |

2.2. Addressing Balance and Cognitive–Motor Deficits

2.3. Individualized Assessment and Ongoing Monitoring

3. Physical Rehabilitation for Dynapenia, Sarcopenia, Sarcopenic Obesity, and Frailty

3.1. Comprehensive Rehabilitation Strategies

3.2. Nutritional and Swallowing Interventions

3.3. Cardiovascular and Functional Enhancement

3.4. Addressing Sedentary Behavior

4. Physical Rehabilitation for Neuro-Motor and Cognitive Deficits

4.1. Targeted Neuromotor and Gait Training

4.2. The Role of Occupational Therapy

4.2.1. Beyond Motor Skills: Impact on Mental and Cognitive Symptoms

4.2.2. The Role of CBT

5. Discussion

5.1. Physical Rehabilitation for Antipsychotic-Related Motor Dysfunction

5.2. Physical Rehabilitation for Dynapenia, Sarcopenia, Sarcopenic Obesity, and Frailty

5.3. Physical Rehabilitation for Neuro-Motor and Cognitive Deficits

5.4. Practical Applications and Clinical Workflow

5.4.1. Holistic and Granular Assessment

5.4.2. Precision Rehabilitation and Individualized Treatment Plans

- Domain 1 (Antipsychotic-related): Patients with pronounced extrapyramidal symptoms (including rigidity and tremor) or significant metabolic side effects (such as obesity) and impaired gait likely fall into this category.

- Domain 2 (Negative symptom-related): Patients with a history of sedentary behavior, significant apathy, or signs of dynapenia/sarcopenia are primarily guided by this domain. These issues are often associated with long-standing behavioral patterns rather than acute medication effects.

- Domain 3 (Neuro-motor and cognitive deficits): If the patient exhibits subtle neuromotor impairments (including gait abnormalities and poor coordination) that predate medication use or persist despite symptom stability, the rehabilitation focus shifts here, addressing central nervous system vulnerabilities.

5.4.3. Enhanced Multidisciplinary Collaboration

5.4.4. Focus on Early and Preventive Intervention

6. Limitations and Recommendations

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADL | Activity of Daily Living |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

References

- World Health Organization. Schizophrenia. WHO Newsroom: Fact Sheets. 10 January 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Laursen, T.M.; Munk-Olsen, T.; Vestergaard, M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2012, 25, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.J.; Jang, M.H. Risk factors of metabolic syndrome in community-dwelling people with schizophrenia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, L.E.; Deenik, J.; Tenback, D.E.; Van Oort, J.; Van Harten, P.N. Exploring the relationship between movement disorders and physical activity in patients with schizophrenia: An actigraphy study. Schizophr. Bull. 2021, 47, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Wu, X. Schizophrenia and obesity: May the gut microbiota serve as a link for the pathogenesis? Imeta 2023, 2, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Ortega, S.; Redondo Del Río, P.; Carreño Enciso, L.; De La Cruz Marcos, S.; Massia, M.N.; De Mateo Silleras, B. Phase angle as a prognostic indicator of survival in institutionalized psychogeriatric patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanioka, R.; Osaka, K.; Ito, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tomotake, M.; Takase, K.; Tanioka, T. Examining factors associated with dynapenia/sarcopenia in patients with schizophrenia: A pilot case-control study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Chen, C.T.; Li, K.P.; Chou, P. Prevalence and impact of frailty among inpatients with schizophrenia: Evidence from the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2005–2020. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2025, 59, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassnig, M.; Signorile, J.; Gonzalez, C.; Harvey, P.D. Physical performance and disability in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2014, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Ninou, A.; Samakouri, M. Mortality in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: Recent advances in understanding and management. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Croatto, G.; Schneider, L.K.; Rohani-Montez, S.C.; Fairley, L.; Smith, N.; Bitter, I.; Gorwood, P.; Taipale, H.; et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M. Psychosocial rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 58, S77–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, V.; Stogios, N.; Agarwal, S.M.; Cheng, A.J. The neuromuscular basis of functional impairment in schizophrenia: A scoping review. Schizophr. Res. 2024, 274, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredin, S.S.D.; Kaufman, K.L.; Chow, M.I.; Lang, D.J.; Wu, N.; Kim, D.D.; Warburton, D.E.R. Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training on psychiatric symptom severity and related health measures in adults living with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 8, 753117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rashid, N.A.; Nurjono, M.; Lee, J. Clinical determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior in individuals with schizophrenia. Asian J. Psychiatry 2019, 46, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szortyka, M.F.; Batista Cristiano, V.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P. Differential physical and mental benefits of physiotherapy program among patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls suggesting different physical characteristics and needs. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 536767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela-Huotari, K. How to craft a compelling storyline for a conceptual paper. AMS Rev. 2024, 14, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, P.F.; Sami, M.B. The mechanisms of persisting disability in schizophrenia: Imprecise predictive coding via corticostriatothalamic-cortical loop dysfunction. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 97, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handest, R.; Molstrom, I.M.; Gram Henriksen, M.; Hjorthøj, C.; Nordgaard, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between psychopathology and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2023, 49, 1470–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheewe, T.W.; Jörg, F.; Takken, T.; Deenik, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Backx, F.J.G.; Cahn, W. Low physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in people with schizophrenia: A comparison with matched healthy controls and associations with mental and physical health. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukdura, J.S.; McClintock, S.M.; Croarkin, P.E. Psychomotor retardation in depression: Biological underpinnings, measurement, and treatment. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharkwal, G.; Brami-Cherrier, K.; Lizardi-Ortiz, J.E.; Nelson, A.B.; Ramos, M.; Del Barrio, D.; Sulzer, D.; Kreitzer, A.C.; Borrelli, E. Parkinsonism driven by antipsychotics originates from dopaminergic control of striatal cholinergic interneurons. Neuron 2016, 91, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, L.; Lerer, B. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders as a resource for better understanding parkinson’s disease modifier genes. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, V.; Latreche, C.; Fanshawe, J.B.; Varvari, I.; Zauchenberger, C.Z.; McGinn, N.; Catalan, A.; Pillinger, T.; McGuire, P.K.; McCutcheon, R.A. Anticholinergic burden and cognitive function in psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2025, 182, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myslivecek, J. Two players in the field: Hierarchical model of interaction between the dopamine and acetylcholine signaling systems in the striatum. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalniunas, A.; James, K.; Pappa, S. Prevalence of spontaneous movement disorders (dyskinesia, parkinsonism, akathisia and dystonia) in never-treated patients with chronic and first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Ment. Health 2024, 27, e301184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Lee, S.C.; Suh, J.H.; Yang, S.N.; Han, K.; Kim, Y.W. Different risks of early-onset and late-onset Parkinson disease in individuals with mental illness. Npj Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.P.; Feng, L.; Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Feng, L.; Gao, Q.; Lim, M.L.; Collinson, S.L.; Chong, M.S.; Lim, W.S.; Lee, T.S.; et al. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia: Follow-up of the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study Cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2016, 73, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Alvarenga, J.C.; Almeida, M.A.; Cavazos, J.E.; Mahaney, M.C.; Maestre, G.E.; Glahn, D.C.; Duggirala, R.; Blangero, J. Impact of type 2 diabetes and hypertension on cognition: A propensity score-matched analysis in Mexican Americans from San Antonio. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, e091135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Yan, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, B.; Xie, W. HbA1c, diabetes and cognitive decline: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deenik, J.; Czosnek, L.; Teasdale, S.B.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Tenback, D.E.; Van Harten, P.N.; Tak, E.C.P.M.; Lederman, O.; et al. From impact factors to real impact: Translating evidence on lifestyle interventions into routine mental health care. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 1070–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagi, K.; Nosaka, T.; Dickinson, D.; Lindenmayer, J.P.; Lee, J.; Friedman, J.; Boyer, L.; Han, M.; Abdul-Rashid, N.A.; Correll, C.U. Association between cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Castillo-García, A.; Lieberman, D.E.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Lucia, A. Obesity and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira Máximo, R.; De Oliveira, D.C.; Ramírez, P.C.; Luiz, M.M.; De Souza, A.F.; Delinocente, M.L.B.; Steptoe, A.; De Oliveira, C.; Da Silva Alexandre, T. Dynapenia, abdominal obesity or both: Which accelerates the gait speed decline most? Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, B.S.; Saravanan, D.; Ganamurali, N.; Sabarathinam, S. A narrative review on the impact of sarcopenic obesity and its psychological consequence in quality of life. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, K.; Ogawa, W.; Kimura, Y.; Kusakabe, T.; Miyazaki, R.; Sanada, K.; Satoh-Asahara, N.; Someya, Y.; Tamura, Y.; Ueki, K.; et al. Diagnosis of sarcopenic obesity in Japan: Consensus statement of the Japanese Working Group on Sarcopenic Obesity. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2024, 24, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, C.; Iemitsu, M.; Kurihara, T.; Kishigami, K.; Miyachi, M.; Sanada, K. Differences in sarcopenia indices in elderly Japanese women and their relationships with obesity classified according to waist circumference, BMI, and body fat percentage. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2024, 43, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, J.; Hill, C.; James, R.S.; Cox, V.M.; Seebacher, F. The effect of obesity on the contractile performance of isolated mouse soleus, EDL, and diaphragm muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.E.; Fisher, S.R.; Bergés, I.M.; Kuo, Y.F.; Ostir, G.V. Walking speed threshold for classifying walking independence in hospitalized older adults. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Ikezoe, T.; Ichihashi, N.; Tabara, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Matsuda, F.; Tsuboyama, T. Relationship of low muscle mass and obesity with physical function in community dwelling older adults: Results from the Nagahama study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 88, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schooten, K.S.; Freiberger, E.; Sillevis Smitt, M.; Keppner, V.; Sieber, C.; Lord, S.R.; Delbaere, K. Concern about falling is associated with gait speed, independently from physical and cognitive function. Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindzielorz, A.; Edwards, H.; Melvin, K. Motor symptoms as a prodrome to schizophrenia. Marshall J. Med. 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, A.; Siuda-Krzywicka, K.; Siwek, G.; Tereszko, A.; Siwek, M.; Dudek, D. Association between implicit motor learning and neurological soft signs in schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 33, S244–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, C.J.; Duval, C.Z.; Schröder, J. Neurological soft signs and cognition in the late course of chronic schizophrenia: A longitudinal study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowiasch, S.; Backasch, B.; Einhäuser, W.; Leube, D.; Kircher, T.; Bremmer, F. Eye movements of patients with schizophrenia in a natural environment. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 266, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehet, M.; Tso, I.F.; Park, S.; Neggers, S.F.W.; Thompson, I.A.; Kahn, R.S.; Thakkar, K.N. Altered effective connectivity within an oculomotor control network in unaffected relatives of individuals with schizophrenia. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ye, J.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Yuan, L.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhong, X.; et al. Predictors of everyday functional impairment in older patients with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1081620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, S.; Maggi, G.; Ilardi, C.R.; Cavallo, N.D.; Torchia, V.; Pilgrom, M.A.; Cropano, M.; Roldán-Tapia, M.D.; Santangelo, G. The relation between cognitive functioning and activities of daily living in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: A meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2427–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnack, H.G.; Van Haren, N.E.M.; Nieuwenhuis, M.; Hulshoff Pol, H.E.; Cahn, W.; Kahn, R.S. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia: A longitudinal pattern recognition study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.L.; Tsai, S.J.; Lin, C.P.; Yang, A.C. Progressive brain abnormalities in schizophrenia across different illness periods: A structural and functional MRI study. Schizophrenia 2023, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International Exercise Recommendations in Older Adults (ICFSR): Expert consensus guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muench, J.; Hamer, A.M. Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 81, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stroup, T.S.; Gray, N. Management of common adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putzhammer, A.; Klein, H.E. Quantitative analysis of motor disturbances in schizophrenic patients. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, S.; Koschorke, P.; Horn, H.; Strik, W. Objectively measured motor activity in schizophrenia challenges the validity of expert ratings. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 169, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, R.; Noronha, C.; Diwadkar, V.A. Motor system dysfunction in the schizophrenia diathesis: Neural systems to neurotransmitters. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 44, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyckt, L.; Wiesel, F.A.; Borg, J.; Edman, G.; Ansved, T.; Sydow, O.; Borg, K. Neuromuscular and psychomotor abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2000, 34, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forhan, M.; Gill, S.V. Obesity, functional mobility and quality of life. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 27, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, S.S.; Ge, R.; Sanford, N.; Modabbernia, A.; Reichenberg, A.; Whalley, H.C.; Kahn, R.S.; Frangou, S. Accelerated global and local brain aging differentiate cognitively impaired from cognitively spared patients with schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 913470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Tan, X.; Zou, J.; Wu, X. A 24-week combined resistance and balance training program improves physical function in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, e62–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, M.; Zhao, H.; Liao, R.; Lu, J.; Tu, J.; Zou, Y.; Teng, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Effect of multicomponent intervention on functional decline in Chinese older adults: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2023, 27, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvetkova, E.; Koytchev, E.; Ivanov, I.; Ranchev, S.; Antonov, A. Biomechanical, healing and therapeutic effects of stretching: A comprehensive review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, S.R.; Sherrington, C.; Naganathan, V. Falls in Older People: Risk Factors, Strategies for Prevention and Implications for Practice, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-108-59445-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lena, F.; Modugno, N.; Greco, G.; Torre, M.; Cesarano, S.; Santilli, M.; Abdullahi, A.; Giovannico, G.; Etoom, M. Rehabilitation interventions for improving balance in Parkinson’s disease: A narrative review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, E.D.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Garcia De Alcaraz Serrano, A.; RaquelHernandez-García, R. Effects of core training on dynamic balance stability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouzi, E.; Vaezmosavi, M.; Gerber, M.; Pühse, U.; Brand, S. Dual-task training on cognition and resistance training improved both balance and working memory in older people. Phys. Sportsmed. 2019, 47, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombini-Souza, F.; De Moura, V.T.G.; Da Silva, L.W.N.; Leal, I.D.S.; Nascimento, C.A.; Silva, P.S.T.; Perracini, M.R.; Sacco, I.C.; De Araújo, R.C.; Nascimento, M.D.M. Effects of two different dual-task training protocols on gait, balance, and cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults: A 24-week randomized controlled trial. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.D.; Allen, N.E.; Canning, C.G.; Fung, V.S.C. Postural instability in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Kubi, K.; Wright, W. Vestibular training promotes adaptation of multisensory integration in postural control. Gait Posture 2019, 73, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennie, S.; Bruner, K.; Dizon, A.; Fritz, H.; Goodman, B.; Peterson, S. Measurements of balance: Comparison of the timed “up and go” test and functional reach test with the Berg balance scale. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2003, 15, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioğlu, A.; Kezban Şahin, Ü.; Acaröz, S. Discriminative ability of the four balance measures for previous fall experience in Turkish community-dwelling older adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2022, 30, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, S.; Iwata, M.; Miyazaki, M.; Fukaya, T.; Yamanaka, E.; Nagata, K.; Tsuchida, W.; Asai, Y.; Suzuki, S. Acute and prolonged effects of 300 sec of static, dynamic, and combined stretching on flexibility and muscle force. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2023, 22, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.E.; Martin, C.L.; Schenkman, M.L. Striding out with Parkinson disease: Evidence-based physical therapy for gait disorders. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, R.; Robinson, K.M. Geriatric rehabilitation. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 104, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennie, J.A.; De Cocker, K.; Pavey, T.; Stamatakis, E.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Ding, D. Muscle strengthening, aerobic exercise, and obesity: A pooled analysis of 1.7 million US adults. Obesity 2020, 28, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, F.; Zhu, D. Effects of aerobic exercise combined with resistance training on body composition and metabolic health in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1409660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Mugisha, J.; Hallgren, M.; Probst, M.; Ward, P.B.; Gaughran, F.; De Hert, M.; et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Delzenne, N.; Demirkan, K.; Schneider, S.; Abbasoglu, O.; Bahat, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Bauer, J.; Cuerda, C.; De Van Der Schueren, M.; et al. Nutrition for the older adult–current concepts. Report from an ESPEN symposium. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1815–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Anno, T.; Ogawa, N.; Kimura, Y.; Kawasaki, F.; Kaku, K.; Kaneto, H.; Takemasa, M.; Sasano, M. Impact of nutritional guidance on various clinical parameters in patients with moderate obesity: A retrospective study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1138685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakehi, S.; Isono, E.; Wakabayashi, H.; Shioya, M.; Ninomiya, J.; Aoyama, Y.; Murai, R.; Sato, Y.; Takemura, R.; Mori, A.; et al. Sarcopenic dysphagia and simplified rehabilitation nutrition care process: An update. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 47, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molfenter, S.M. The relationship between sarcopenia, dysphagia, malnutrition, and frailty: Making the case for proactive swallowing exercises to promote healthy aging. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretchen-Doorly, D.; Kite, R.E.; Subotnik, K.L.; Detore, N.R.; Ventura, J.; Kurtz, A.S.; Nuechterlein, K.H. Cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular flexibility and strength in first-episode schizophrenia patients: Use of a standardized fitness assessment. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2012, 6, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Liu, Z.; Liang, C.; Zhao, Z. Comparative efficacy of different types of exercise modalities on psychiatric symptomatology in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review with network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.M.; Liu, S.Y.; Sun, P.; Li, W.L.; Lian, Z.Q. Effects of low intensity resistance training of blood flow restriction with different occlusion pressure on lower limb muscle and cardiopulmonary function of college students. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi Zhongguo Yingyong Shenglixue Zazhi Chin. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 36, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabero-Garrido, R.; Del Corral, T.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Sanz-Ayan, P.; Izquierdo-García, J.; López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I. Effects of respiratory muscle training on exercise capacity, quality of life, and respiratory and pulmonary function in people with ischemic heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. 2024, 104, pzad164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, M. Osteoarthritis, obesity and type 2 diabetes: The weight of waist circumference. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garcia, P.; Plaza-Florido, A.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Torres-Lopez, L.V.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Ortega, F.B. Role of physical fitness and functional movement in the body posture of children with overweight/obesity. Gait Posture 2020, 80, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignoux, P.; Lanhers, C.; Dutheil, F.; Boutevillain, L.; Pereira, B.; Coudeyre, E. Non-rigid lumbar supports for the management of non-specific low back pain: A literature review and meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 65, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Hanley, C.; Nimon, J.P.; Westen, S.C. Cognitive health benefits of strengthening exercise for community-dwelling older adults. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2010, 32, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattyn, N.; Vanhees, L.; Cornelissen, V.A.; Coeckelberghs, E.; De Maeyer, C.; Goetschalckx, K.; Possemiers, N.; Wuyts, K.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Beckers, P.J. The long-term effects of a randomized trial comparing aerobic interval versus continuous training in coronary artery disease patients: 1-Year data from the SAINTEX-CAD study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvsannyam, E.; Jain, M.S.; Pormento, M.K.L.; Siddiqui, H.; Balagtas, A.R.A.; Emuze, B.O.; Poprawski, T. Neurobiology of schizophrenia: A comprehensive review. Cureus 2022, 14, e23959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Bella, S. The use of rhythm in rehabilitation for patients with movement disorders. In Music and the Aging Brain; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 383–406. ISBN 978-0-12-817422-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González, P.; Carratalá-Tejada, M.; Monge-Pereira, E.; Collado-Vázquez, S.; Sánchez-Herrera Baeza, P.; Cuesta-Gómez, A.; Oña-Simbaña, E.D.; Jardón-Huete, A.; Molina-Rueda, F.; Balaguer-Bernaldo De Quirós, C.; et al. Leap motion controlled video game-based therapy for upper limb rehabilitation in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A feasibility study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanioka, R.; Yasuhara, Y.; Osaka, K.; Kai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tanioka, T.; Takase, K.; Dino, M.J.S.; Locsin, R.C. Autonomic nervous activity of patient with schizophrenia during pepper CPGE-led upper limb range of motion exercises. Enferm. Clínica 2020, 30, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.M.; Rubens, A.; Silva, D.; Terra, M.B.; Almeida, I.A.; Lúcio, B.; Melo, D.; Ferraz, H.B. Balance versus resistance training on postural control in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamborg, M.; Hvid, L.G.; Dalgas, U.; Langeskov-Christensen, M. Parkinson’s disease and intensive exercise therapy—an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 145, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanioka, R.; Kamoi, R.; Mifune, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Onishi, K.; Soriano, K.; Umehara, H.; Ito, H.; Bollos, L.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; et al. Gait disturbance in patients with schizophrenia in relation to walking speed, ankle joint range of motion, body composition, and extrapyramidal symptoms. Healthcare 2025, 13, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuang, Y.P.; Huang, C.L.; Wu, C.S. Haptic perception training programs on fine motor control in adolescents with developmental coordination disorder: A preliminary study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byl, N.N.; McKenzie, A. Treatment effectiveness for patients with a history of repetitive hand use and focal hand dystonia. J. Hand Ther. 2000, 13, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, M.; Couillandre, A.; Mseddi, E.; Termoz, N.; Abidi, M.; Bardinet, E.; Delgadillo, D.; Lenglet, T.; Querin, G.; Welter, M.L.; et al. Extrapyramidal deficits in ALS: A combined biomechanical and neuroimaging study. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Abi-Dargham, A.; Howes, O. Emerging treatments in schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 83, SU21024IP1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.M.; Brando, F.; Pezzella, P.; De Angelis, M.; Mucci, A.; Galderisi, S. Factors influencing the outcome of integrated therapy approach in schizophrenia: A narrative review of the literature. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 970210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Thinking and depression. I. idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1963, 9, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykes, T.; Steel, C.; Everitt, B.; Tarrier, N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr. Bull. 2008, 34, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.P.; Turkington, D.; Pyle, M.; Spencer, H.; Brabban, A.; Dunn, G.; Christodoulides, T.; Dudley, R.; Chapman, N.; Callcott, P.; et al. Cognitive therapy for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders not taking antipsychotic drugs: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.C.; Dahlen, E.R. Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 39, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Prevention and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4731-0428-0. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555203/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Piasecki, M.; Atherton, P.J. The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: Measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy and muscle fiber loss in humans. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoi, R.; Mifune, Y.; Soriano, K.; Tanioka, R.; Yamanaka, R.; Ito, H.; Osaka, K.; Umehara, H.; Shimomoto, R.; Bollos, L.A.; et al. Association between dynapenia/sarcopenia, extrapyramidal symptoms, negative symptoms, body composition, and nutritional status in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Healthcare 2024, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.S.; Aslam, S.P.; Hooten, W.M. Extrapyramidal side effects. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nadesalingam, N.; Chapellier, V.; Lefebvre, S.; Pavlidou, A.; Stegmayer, K.; Alexaki, D.; Gama, D.B.; Maderthaner, L.; Von Känel, S.; Wüthrich, F.; et al. Motor abnormalities are associated with poor social and functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 115, 152307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesh, T.A.; Niendam, T.A.; Minzenberg, M.J.; Carter, C.S. Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: Mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 316–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C.; Salameh, P.; Sacre, H.; Clément, J.P.; Calvet, B. General description of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and assessment tools in Lebanon: A scoping review. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2021, 25, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofheinz, M.; Mibs, M.; Elsner, B. Dual task training for improving balance and gait in people with stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD012403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, A.; Tavakol, K.; Scholten, J.; Mathis, D.; Maron, D.; Bakhshi, S. The role of dual tasking in the assessment of gait, cognition and community reintegration of veterans with mild traumatic brain injury. Mater. Socio Medica 2017, 29, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, T.; Shang, H. The impact of motor-cognitive dual-task training on physical and cognitive functions in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Writing group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassnig, M.T.; Harvey, P.D.; Miller, M.L.; Depp, C.A.; Granholm, E. Real world sedentary behavior and activity levels in patients with schizophrenia and controls: An ecological momentary assessment study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2021, 20, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, G.; Kim, C.E.; Ryu, S. Physical activity of patients with chronic schizophrenia and related clinical factors. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcwiartek, C.; Jensen, S.E.; Frøkjær, J.B.; Nielsen, R.E. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease in patients with schizophrenia: Baseline results from a prospective cohort study with long-term clinical follow-up. Schizophrenia 2025, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, S.; Lindblom, Y.; Mjörndal, T.; Adolfsson, R. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among a Swedish cohort of patients with schizophrenia. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 21, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, B.H. Motor rehabilitation after stroke, traumatic brain, and spinal cord injury: Common denominators within recent clinical trials. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2009, 22, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdler, S.J.; Confino, J.E.; Woesner, M.E. Exercise as a treatment for schizophrenia: A review. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2019, 49, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccione, C.; di Scalea, G.L.; Ambrosecchia, M.; Terrone, G.; Di Cesare, G.; Ducci, G.; Schimmenti, A.; Caretti, V. Early signs of schizophrenia and autonomic nervous system dysregulation: A literature review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2019, 16, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsgodt, K.H.; Sun, D.; Cannon, T.D. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in schizophrenia. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rehabilitation Focus | Rationale & Key Interventions | Characteristics of Schizophrenia | Comparative Insight | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle and motor function | Strength and resistance training to enhance muscle mass and adaptability. | Sarcopenia and dynapenia are accelerated by sedentary behavior caused by negative symptoms and cognitive deficits. | Unlike age-related sarcopenia, the driving factors are behavioral (sedentary lifestyle) and symptom-related, requiring a focus on motivational strategies. | [62,63] |

| Cardiovascular & metabolic health | Aerobic and interval training to improve cardiorespiratory fitness and reduce metabolic risk. | High prevalence of metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular disease due to sedentary behavior and antipsychotic medication. | Although relevant to many chronic conditions, the rate of decline is significantly accelerated in this population, necessitating early, aggressive intervention. | [31,39,83,84,90,91] |

| Nutrition & metabolic Balance | Collaborative rehabilitation-nutrition approach to ensure adequate protein intake and metabolic health. | Malnutrition and poor dietary habits exacerbate muscle wasting and frailty, often coexisting with symptoms. | This is a crucial element that links physical therapy with nutritional care, which is often overlooked in general rehabilitation models. | [79,80,82] |

| Swallowing function | Exercise and protein supplementation to strengthen swallowing muscles. | Dysphagia and aspiration risk are associated with sarcopenia of the swallowing muscles, a complication of severe frailty. | This is a specialized need that is directly connected to overall physical decline, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive approach to frailty management. | [81,82] |

| ADL | Task-oriented training to improve walking speed, movement efficiency, and social participation. | Reduced ADL independence due to both physical and behavioral factors (such as lack of motivation from negative symptoms). | The focus is not just on physical capacity but also on re-engaging patients in purposeful activities, which addresses the behavioral aspects unique to schizophrenia. | [34,37,78] |

| Rehabilitation Focus | Rationale & Key Interventions | Characteristics of Schizophrenia | Comparative Insight | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuromotor function | Rhythmic exercises and core training to improve motor coordination and postural control. | Motor and gait dysfunctions are not solely medication-induced but also associated with central nervous system vulnerabilities and disuse syndrome. | This approach differs from typical Parkinson’s disease rehabilitation, as the underlying cause is more complex and not strictly dopaminergic, requiring a broader focus on neuroplasticity and motor control. | [93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Cognitive–motor integration | Dual-task and visual–vestibular training to enhance attention and executive function. | Cognitive deficits (including attention and working memory) directly impair a patient’s ability to perform complex motor tasks and navigate their environment safely. | This is a unique dual-benefit approach that directly addresses the simultaneous impairment of both cognitive and motor domains, which is a major challenge in schizophrenia. | [67,68,69,70] |

| Functional Motor Skills | Fine motor training and sensory integration therapy to improve the execution of ADLs and IADLs. | Fine motor deficits and sensory-motor impairments contribute to a loss of independence and social withdrawal. | This emphasizes a holistic approach that bridges physical limitations with real-life functional tasks, which is essential for improving social participation and quality of life, a key goal in schizophrenia rehabilitation. | [55,99,100,101] |

| Psychiatric symptom improvement | Moderate physical activity and regular exercise to improve motivation and cognitive function. | Physical activity not only improves motor function but also directly alleviates positive/negative symptoms, enhances motivation, and promotes goal-directed behavior. | This is a unique dual-benefit aspect of physical rehabilitation in schizophrenia that is less pronounced in purely physical conditions, making it a powerful adjunctive treatment. | [65,102,103] |

| CBT | Cognitive restructuring, goal-setting, and self-monitoring to address distorted cognitions and enhance self-efficacy. | CBT improves positive/negative symptoms and cognitive functions. When combined with physical rehab, it enhances motivation and adherence. | CBT is an important psychosocial adjunct to physical rehabilitation, offering an integrated approach to improve quality of life and prevent relapse. | [103,104,105,106,107,108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanioka, R.; Onishi, K.; Betriana, F.; Bollos, L.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; Tang, A.C.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Mifune, Y.; Mifune, K.; Tanioka, T. Targeted Physical Rehabilitation for Physical Function Decline in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040136

Tanioka R, Onishi K, Betriana F, Bollos L, Kwan RYC, Tang ACY, Zhao Y, Mifune Y, Mifune K, Tanioka T. Targeted Physical Rehabilitation for Physical Function Decline in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(4):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040136

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanioka, Ryuichi, Kaito Onishi, Feni Betriana, Leah Bollos, Rick Yiu Cho Kwan, Anson Chui Yan Tang, Yueren Zhao, Yoshihiro Mifune, Kazushi Mifune, and Tetsuya Tanioka. 2025. "Targeted Physical Rehabilitation for Physical Function Decline in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review" Psychiatry International 6, no. 4: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040136

APA StyleTanioka, R., Onishi, K., Betriana, F., Bollos, L., Kwan, R. Y. C., Tang, A. C. Y., Zhao, Y., Mifune, Y., Mifune, K., & Tanioka, T. (2025). Targeted Physical Rehabilitation for Physical Function Decline in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Psychiatry International, 6(4), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040136