Functioning of Neurotypical Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Addressing the Gaps in the Literature

1.2. Objectives of This Review

- -

- Synthesize existing research on the emotional, psychological, and social functioning of NT siblings of children with ASD.

- -

- Identify protective and risk factors that shape their adaptation, considering individual and family-level influences.

- -

- Examine the reciprocal nature of sibling interactions, integrating the experiences of both NT and autistic siblings.

- -

- Compare the challenges faced by NT siblings in ASD families to those in families with other developmental conditions, clarifying the uniqueness of ASD-related sibling experiences.

- -

- Provide practical insights for clinical and educational interventions, emphasizing family-centered approaches to support both NT and autistic siblings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Empirical studies (quantitative or qualitative) examining the psychological, emotional, behavioral, and social functioning of neurotypical (NT) siblings of individuals with ASD.

- -

- Articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 2013 and 2024.

- -

- Studies written in English.

- -

- Research using validated assessment tools for sibling well-being and family dynamics.

- -

- Studies focusing only on parental perspectives, without assessing sibling outcomes.

- -

- Case reports, theoretical papers, or conference abstracts.

- -

- Studies lacking clear methodological descriptions or conducted on non-representative small samples.

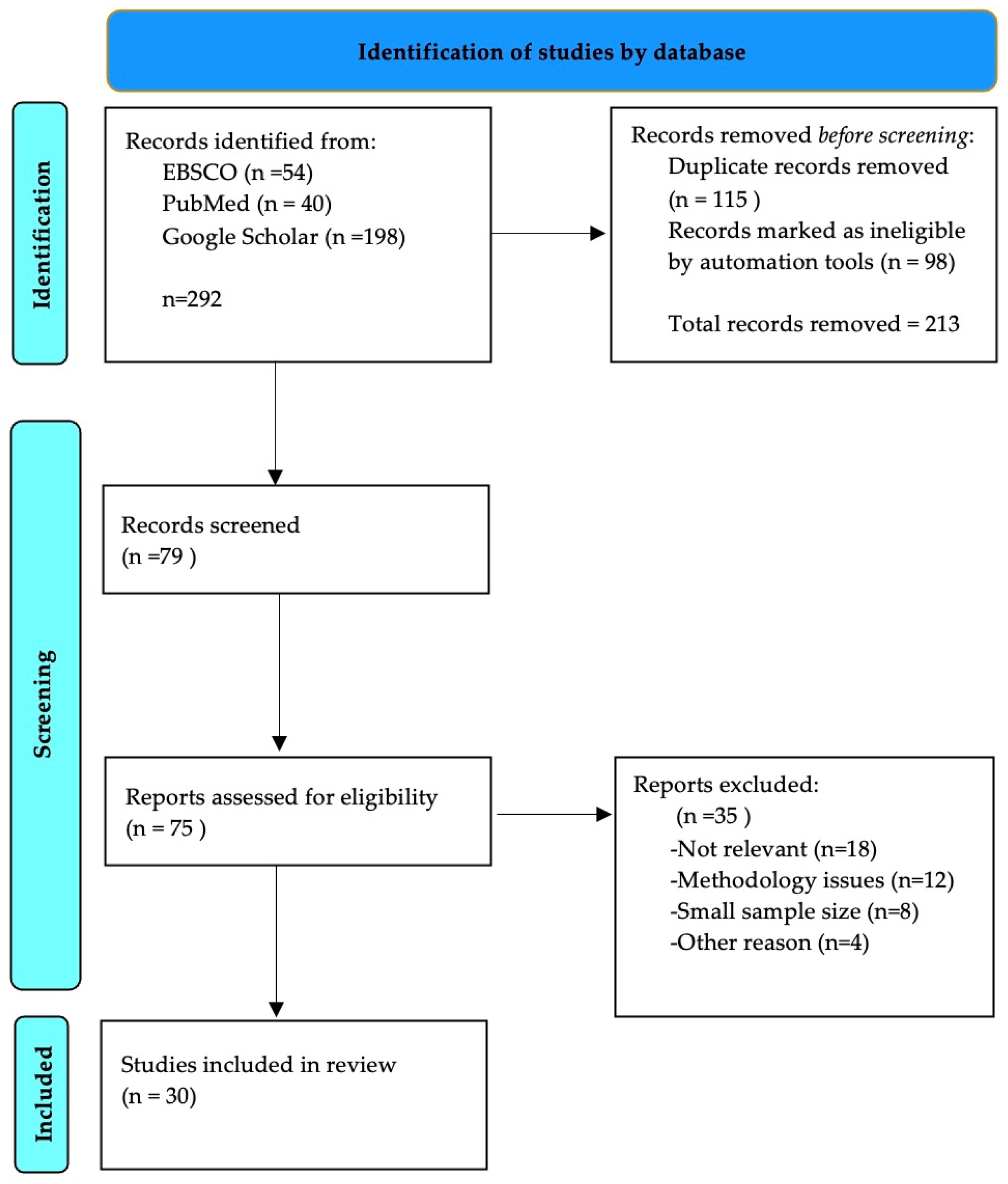

2.3. Study Selection Process

- -

- Title and abstract screening—Two independent reviewers (B.C., A.B.) assessed the relevance of each study based on the predefined criteria.

- -

- Full-text evaluation—Eligible articles were retrieved and further assessed for methodological rigor.

- -

- Final selection—Discrepancies in study selection were resolved through a systematic consensus process to ensure objectivity.

- -

- Each stage was independently conducted by four reviewers (B.C., A.B., C.I., G.M.L.P.) to reduce bias and improve the reliability of study selection.

2.4. Inter-Rater Reliability

3. Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings: A Complex and Multifaceted Reality

- (1)

- The Emotional and Psychological Impact on NT Siblings

- (2)

- The Social and Behavioral Functioning of NT Siblings

- (3)

- Protective Factors and the Role of Social Support

4.2. Strengths of the Review

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Clinical and Educational Implications

- (1)

- Family-Centered Interventions

- (2)

- School-Based Interventions

- (3)

- Psychological Support and Resilience Training

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Picardi, A.; Gigantesco, A.; Tarolla, E.; Stoppioni, V.; Cerbo, R.; Cremonte, M.; Nardocci, F. Parental burden and its correlates in families of children with autism spectrum disorder: A multicentre study with two comparison groups. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, R.P. Brief Report: Behavioral Adjustment of Siblings of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Seltzer, M.M. Siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders across the life course. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, C.M.; Jackson, J.B.; McGregor, C.M. Functioning among Typically Developing Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, L.; Dewey, D. Sibling Relationships of Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, M.E.; Lerner, M.D. A Model of Family Functioning in Siblings of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1210–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervás, A. One autism, several autisms. Phenotypical variability in autism spectrum disorders. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 62, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Siemann, J.K.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Wallace, M.T. Approaches to understanding multisensory dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1430–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macks, R.J.; Reeve, R.E. The adjustment of non-disabled siblings of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolfi, M. Terapia Familiar: Un Enfoque Interaccional; Paidós Terapia Familiar: Barcelona, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin, P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Bron 1985, 56, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Solmeyer, A.R.; McHale, S.M. The third rail of family systems: Sibling relationships, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, L.L.; Davenport, R.; Schmiege, C. Supporting siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Early Child. Educ. J. 2012, 40, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak-Levy, Y.; Goldstein, E.; Weinstock, M. Adjustment characteristics of healthy siblings of children with autism. J. Fam. Stud. 2010, 16, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, S.M.; Updegraff, K.A.; Feinberg, M.E. Siblings of youth with autism spectrum disorders: Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships and individual adjustment. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, D. On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem’. Disabil. Soc. 2012, 27, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nißen, M.; Rüegger, D.; Stieger, M.; Flückiger, C.; Allemand, M.; von Wangenheim, F.; Kowatsch, T. The effects of health care chatbot personas with different social roles on the client-chatbot bond and usage intentions: Development of a design codebook and web-based study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e32630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abualait, T.; Alabbad, M.; Kaleem, I.; Imran, H.; Khan, H.; Kiyani, M.M.; Bashir, S. Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children: Early Signs and Therapeutic Interventions. Children 2024, 11, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.j.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.Y.; Kassim, S.N.Z.B.; Gan, C.H.; Fierro, V.; Chan, C.M.H.; Hersh, D. “Sometimes I feel grateful…”: Experiences of the adolescent siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder in Malaysia. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouzos, A.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Tassi, C. A psychoeducational group intervention for siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Spec. Group Work 2017, 42, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.M.; Benigno, J.P. Autism spectrum disorder and sibling relationships: Exploring implications for intervention using a family systems framework. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2019, 28, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidotti, L.; Musetti, A.; Barbieri, G.L.; Ballocchi, I.; Corsano, P. Conflicting and harmonious sibling relationships of children and adolescent siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Care Health Dev. 2021, 47, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koukouriki, E.; Soulis, S.G.; Andreoulakis, E. Depressive symptoms of autism spectrum disorder children’s siblings in Greece: Associations with parental anxiety and social support. Autism 2021, 25, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Cheng, C.M.; Huang, K.L.; Hsu, J.W.; Bai, Y.M.; Tsai, S.J.; Chen, M.H. Developmental and mental health risks among siblings of patients with autism spectrum disorder: A nationwide study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 31, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantor, J.; Smrčková, A.; De Goumoëns, V.; Munn, Z.; Svobodová, Z.; Klugar, M. Experience of having a sibling with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 2406–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouriki, E.; Athanasopoulou, E.; Andreoulakis, E. Feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction in siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders: The role of birth order and perceived social support. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 4722–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, A.; Chang, Y.; Maharaj, R.; Wang, W.; Fiani, T.; McHugh, S.; Feinup, D.M.; Jones, E.A. Quality of the sibling relationship when one sibling has autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial of a sibling support group. Autism 2022, 26, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Itzchak, E.; Nachshon, N.; Zachor, D.A. Having siblings is associated with better social functioning in autism spectrum disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomeny, T.S.; Barry, T.D.; Fair, E.C.; Riley, R. Parentification of adult siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.Y.; Lai, K.Y. Psychological adjustment of siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder in Hong Kong. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2016, 26, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S.; Sacrey, L.A.R.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bryson, S.; Brian, J.; Smith, I.M.; Garon, N. Relationship between early social-emotional behavior and autism spectrum disorder: A high-risk sibling study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 2527–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlthau, K.A.; Traeger, L.; Luberto, C.M.; Perez, G.K.; Goshe, B.M.; Fell, L.; Park, E.R. Resiliency intervention for siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized pilot trial. Acad. Pediatr. 2023, 23, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiranta-Olkoniemi, E.; Cheslack-Postava, K.; Sucksdorff, D.; Suominen, A.; Gyllenberg, D.; Chudal, R.; Sourander, A. Risk of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders among siblings of probands with autism spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Johner, R.; Chalmers, D.; Novik, N. Sibling Relationships and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Different Relationship. Can. Soc. Work 2019, 20, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, C.; Prino, L.E.; Gastaldi, F.G.M.; Jungert, T. Sibling relationships, personality traits, emotional, and behavioral difficulties in autism spectrum disorders. Child Dev. Res. 2019, 2019, 9576484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braconnier, M.L.; Coffman, M.C.; Kelso, N.; Wolf, J.M. Sibling relationships: Parent–child agreement and contributions of siblings with and without ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryzak, L.A.; Jones, E.A. Sibling self-management: Programming for generalization to improve interactions between typically developing siblings and children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2017, 20, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, D.; Carballo, G.; Garcia-Retamero, R. Siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders: Social support and family quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, C.; Bornman, J.; Donohue, D.; Harty, M. The attitudes of typically developing adolescents towards their sibling with autism spectrum disorder. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2017, 64, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Toseeb, U.; McChesney, G.; Wolke, D. The prevalence and psychopathological correlates of sibling bullying in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 2308–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrosi, G.; Genovese, D.; Amodio, E.; Tripi, G. The quality of life among siblings of autistic individuals: A scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkman, A.H.; Barry, T.D.; Lindsey, R.A. The relation of parental expressed emotion, parental affiliate stigma, and typically-developing sibling internalizing behavior in families with a child with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 4591–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orm, S.; Vatne, T.; Haukeland, Y.B.; Silverman, W.K.; Fjermestad, K. The validity of a measure of adjustment in siblings of children with developmental and physical disabilities: A brief report. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2021, 24, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.N.; Bagawan, A.; West, P. A Theory-Generating Qualitative Meta-Synthesis to Understand Neurotypical Sibling Perceptions of Their Relationship with Siblings with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 11, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Hanna, P.; Jones, C.J. A systematic review of the experience of being a sibling of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.; Bryant, M. Sibling-based treatments for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Int. J. Syst. Ther. 2024, 35, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokoena, N.; Kern, A. Experiences of siblings to children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 959117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, S.; Hidalgo, V.; Jiménez, L. ‘That’s just the way it is’: The experiences of co-habiting Spanish siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2025, 34, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restoy, D.; Oriol-Escudé, M.; Alonzo-Castillo, T.; Magán-Maganto, M.; Canal-Bedia, R.; Díez-Villoria, E.; Gisbert-Gustemps, L.; Setién-Ramos, I.; Martínez-Ramírez, M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; et al. Emotion Regulation and Emotion Dysregulation in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Evaluation and Intervention Studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 109, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author-Year | Objective | Type of Study | Sample | Methods | Main Results | Clinical Implications | Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chu et al., 2023 [21] | Exploring the lived experiences and perceptions of adolescents with siblings with ASD in Malaysia. | Qualitative study with semi-structured interviews. | Adolescents with typical development who have a sibling/sister with ASD (n = n.s.) | Semi-structured interviews followed by thematic analysis to explore communication difficulties and emotional coping strategies. | Communication difficulties with ASD siblings; mixed emotions; emotional self-regulation as a coping strategy; closer relationships. | It indicates the need for specific supports for these adolescents, useful for professionals such as speech therapists and other health professions. | Sample limited to Malaysia; results may not be generalizable to other cultural contexts. |

| Tudor, Rankin, and Lerner, 2018 [22] | To examine the clinical needs and functioning of neurotypical siblings of youth with ASD. | Quantitative study with path analysis. | 239 mothers of young people (6–17 years old) with at least one child with ASD and another neurotypical child. | Standardized online measures of family factors and TD sibling outcomes, with path analysis to identify key predictors. | Only 6–23% of siblings were identified in the clinical range for emotional, behavioral or social functioning. Maternal depression and sibling relationship quality were identified as key pathways for sibling functioning. | The findings may guide the development of targeted interventions to improve the functioning of neurotypical siblings in families with ASD. | Based on self-reported data from mothers, which could introduce bias; sample limited to households with Internet access. |

| Brouzos, Vassilopoulos, and Tassi, 2017 [23] | To examine the effectiveness of an 8-week psychoeducational group program for siblings of children with ASD. | Experimental study with control group. | 38 siblings of children with ASD, aged 6–15 years. | Self-report questionnaires administered before and after intervention; experimental (n = 22) and control (n = 16) groups. | Significant increase in knowledge about ASD and reduction in adjustment difficulties and emotional/behavioral problems in the experimental group. | The results support the use of psychoeducational groups to improve the psychological adjustment of siblings of children with ASD. | Relatively small sample; lack of long-term follow-up to verify sustainability of results. |

| Wright and Benigno, 2019 [24] | Exploring sibling involvement in the development and implementation of interventions for children with ASD through the framework of family systems theory (FST). | Theoretical review and analysis of clinical practices. | Not specified. | Review of the basic principles of FST, followed by a review of the state of research on sibling relationships in ASD and the role of siblings in interventions. | Factors such as developmental level, communication status, and areas of strength and challenge are crucial in promoting positive sibling involvement and optimal family functioning. | Stresses the need to develop family-centered intervention programs that consider the unique characteristics of each household to optimize outcomes. | The theoretical nature of the article limits the availability of direct empirical data; further research is needed to validate the conclusions. |

| Guidotti et al., 2021 [25] | Investigating the experience of neurotypical siblings of children with ASD by combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies. | Mixed study with explanatory sequential drawing. | 44 neurotypical siblings of children with ASD, ages 6–17 years. | Inventory of fraternal relationships to assess warmth, rivalry and conflict; participant drawings analyzed with Pictorial Assessment of Interpersonal Relationships. | Neurotypical siblings show affection, but males show more conflict than females. Drawings indicate more cohesion in harmonious situations and more distance in conflicts; adolescents show more annoyance, shame and embarrassment than children. | The combined use of quantitative and qualitative tools, such as drawing, is useful in gaining a detailed understanding of neurotypical siblings’ experiences, informing more personalized interventions. | Relatively small sample; generalizability may be limited, and qualitative analysis may be subject to subjective interpretation. |

| Koukouriki, Soulis, and Andreoulakis. (2021) [26] | To investigate associations between depressive symptoms of neurotypical siblings of children with ASD and parental mental health, perceived social support, and demographic factors. | Quantitative correlational study. | 85 neurotypical siblings of children with ASD and their parents in Greece. | Self-administered questionnaires to assess depressive symptoms (Children’s Depression Inventory), parental mental health (General Health Questionnaire-28) and perceived social support (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support). | Neurotypical siblings show higher levels of depressive symptoms than normative data. Depressive symptoms are significantly associated with parental anxiety and perceived social support, but social support does not attenuate the association between parental anxiety and depressive symptoms in siblings. | It highlights the need for family-centered interventions that take into account both the psychological status of parents and neurotypical siblings, not limiting only to social support. | Sample limited to Greece; results may not be generalizable to other cultural populations; use of self-administered questionnaires may introduce response bias. |

| Lin et al. (2021) [27] | To examine the risks of mental and developmental disorders in unaffected siblings of individuals with ASD. | Longitudinal study based on national database. | 1304 unaffected siblings of ASD probands and 13,040 controls matched for age, sex, and family structure in Taiwan. | Use of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database to follow participants from 1996 or birth through 2011. Identification of developmental delays, language disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, unipolar depression, and disruptive behavior disorders. | Unaffected siblings of individuals with ASD have a higher risk of developing developmental delays, intellectual disability, ADHD, anxiety disorders, unipolar depression, and disruptive behavior disorders than controls. | It emphasizes the importance of monitoring the development and mental health of unaffected siblings of individuals with ASD, suggesting the need for specific clinical and public attention. | Study limited to Taiwan, which may limit the generalizability of the results; mechanisms underlying the observed associations were not explored. |

| Kantor et al., 2023 [28] | Understanding the experiences of neurotypical siblings of people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). | Systematic review. | Qualitative studies of neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD, without limitations on age, sex, or background. | Review conducted according to JBI methodology for qualitative reviews, with a three-step search strategy on various databases without period or language restrictions (but with English abstract/title). | Neurotypical siblings’ experiences range from the positive (increased empathy, ability to cope with challenges) to the negative (increased risk of bullying). Many siblings do not receive adequate support to cope with challenges. | Highlights the need to develop targeted interventions and supports for neurotypical siblings to improve their emotional and social well-being. | Potential variation in quality of included studies; risk of bias in study selection; dependence on English abstracts/titles may exclude relevant studies in other languages. |

| Koukouriki, Athanasopoulou, and Andreoulakis, 2022 [29] | Investigating feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction in neurotypical siblings of children with ASD. | Quantitative correlational study. | 118 neurotypical siblings of children with ASD and 115 siblings of children with typical development. | Administration of questionnaires to assess loneliness, social dissatisfaction and perceived social support by parents; use of multiple hierarchical regressions. | Siblings of children with ASD reported higher levels of loneliness and social dissatisfaction than controls. Being first-born and perceived social support from parents are associated with lower feelings of loneliness. | It suggests the need for specific interventions for younger siblings of children with ASD, beyond simple social support, to reduce feelings of loneliness and improve their well-being. | Limited sample, potential generalizability reduced to other cultural contexts; study relies on self-reported measures, which may introduce bias. |

| Shivers, Jackson, and McGregor, 2019 [30] | Meta-analytically aggregate effect sizes on outcomes of neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD compared with comparison groups. | Meta-analysis of quantitative studies. | 69 independent samples of neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD. | Inclusion of studies with neurotypical siblings (ASD-Sibs) older than 5 years reporting on emotional, psychological, behavioral, or social functioning; calculation of effect sizes. | Neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD have significantly more negative outcomes than the comparison groups, particularly with regard to internalizing behavior problems, psychological functioning, disability beliefs, and anxiety and depression symptoms. | The results suggest the importance of including neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD in family interventions and support strategies to mitigate the risks of negative outcomes. | Aggregate results may hide significant individual differences; generalizability of results may be limited by the quality and variability of included studies. |

| Ben-Itzchak, Nachshon, and Zachor, 2019 [31] | To examine how autism severity and social functioning are affected by the presence of older or younger siblings. | Retrospective study. | 150 children with ASD (mean age = 4:0 ± 1:6) divided into three groups (without siblings, with older siblings, with younger siblings). | Standardized neurological and behavioral assessments to examine autism severity and adaptive social skills; analysis of variance explained by social interactions and family characteristics. | Children with ASD with older siblings show less severe social interaction deficits and better social skills than only children. There are no significant differences between children with younger siblings and the other groups. | It emphasizes the importance of considering the positive role of older siblings in the development of social skills of children with ASD, suggesting that intervention programs could benefit from the involvement of older siblings. | Retrospective study with potential limitations in generalization; does not explore specific mechanisms through which older siblings influence social development. |

| Tomeny, Barry, and Fair, 2017 [32] | To examine how “parentification” (caregiving role assumed by neurotypical siblings) interacts with social support in predicting distress and relational attitudes among adult neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD. | Quantitative correlational study. | 60 adult neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD. | Measurement of perceived social support and parentification (focused on parents or siblings) during childhood; moderation analysis to assess the interaction between parentification and social support on distress and relational attitudes. | Perceived social support moderates the effect of parentification on emotional distress: siblings with high parent-focused parentification and low current social support report more distress. Siblings with low sibling-focused parentification and low social support report less positive attitudes toward their siblings with ASD. | Perceived social support could be a point of intervention to reduce distress and improve fraternal relationships in adult neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD. | Relatively small and specific sample; results may not be generalizable to other populations or cultural contexts; correlational design does not allow for causality. |

| Chan and Lai, 2016 [33] | Exploring the psychological adjustment of neurotypical siblings of children with ASD in Hong Kong. | Quantitative correlational study. | 116 families with neurotypical siblings of children with ASD and learning disabilities. | Parents completed questionnaires on siblings’ emotional and behavioral adjustment, mental well-being, quality of life, and family functioning. Siblings completed a questionnaire on their relationship with the autistic proband. | Parental evaluations did not reveal a significant negative impact on the emotional and behavioral adjustment of neurotypical siblings, but concerns emerged regarding peer relationships and weak prosocial behaviors. Parental quality of life and family functioning were found to be significant predictors of sibling adjustment. | Adopting a holistic approach to address the psychosocial needs of parents can facilitate the adjustment of neurotypical siblings, with a focus on peer relationships and prosocial behaviors. | Study limited to a specific cultural context (Hong Kong); results may not be generalizable to other cultures; use of self-reported questionnaires may introduce response bias. |

| Raza et al., 2020 [34] | Examining social-emotional behavior in children at high risk (HR) of ASD and predicting symptoms and subsequent diagnosis of ASD. | Longitudinal study with diagnostic assessments. | HR children (siblings of children with ASD) and LR children (without family history of ASD). | Social-emotional assessment at 18 months via Infant-Toddler Social-Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) and blind diagnostic assessment for ASD at 36 months. | HR children later diagnosed with ASD showed greater impairment in social-emotional functioning than other HR and LR children. Differences in ITSEA domains and subdomains predicted symptoms and later ASD diagnosis. | It emphasizes the importance of considering early social-emotional development in ASD risk assessment, suggesting that careful monitoring could improve early diagnosis and interventions. | The limited accuracy of classification for ASD, with varying sensitivity and specificity values, suggests the need for further research to improve early screening tools. |

| Kuhlthau et al., 2023 [35] | To examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of a virtual resilience intervention for neurotypical adolescent siblings of children with ASD. | Randomized controlled pilot study with waiting list. | 14–17-year-old neurotypical siblings of children with ASD. | Modification of the Stress Management and Resiliency Training-Relaxation Response Resiliency Program for siblings of children with ASD. Eight weekly 60-min sessions via videoconference. Evaluation of stress management and resilience by independent sample t-tests and effect size calculations. | The intervention group (IG) showed relative improvements over the control group (WLC) in stress management (d = 0.60) and resilience (d = 0.24). Most participants practiced relaxation exercises at least “a few times a week”. | This pilot study suggests that the “SibChat” intervention could be an effective way to improve resilience and stress management skills in neurotypical siblings of adolescents with ASD, warranting further testing and program development. | Small study size; preliminary results requiring confirmation through larger studies; long-term follow-up not evaluated, limiting understanding of sustainability of effects. |

| Jokiranta-Olkoniemi et al., 2016 [36] | To examine the risk of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders among siblings of individuals with ASD. | Nested case-control study based on Finnish national registries. | 3578 cases with ASD and 11,775 controls with 6022 and 22,127 siblings, respectively. | Analysis of data from the Finnish Prenatal Study of Autism and Autism Spectrum Disorders, which included children born between 1987 and 2005, diagnosed with ASD through 2007. Analysis of adjusted risk of disorders among siblings of probands with ASD compared with siblings of controls. | Siblings of individuals with ASD have a significantly higher risk of developing psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders than controls. The highest risks were observed for disorders with childhood onset, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning and coordination disorders, and conduct and opposition disorders. | The results suggest that there is familial clustering of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders among siblings of individuals with ASD, indicating the need for monitoring and preventive interventions for this high-risk population. | The study is limited to Finnish national registries, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other populations; moreover, the mechanisms underlying the observed clustering have not been explored. |

| Day et al., 2019 [37] | Understand the lived experiences of siblings who live or have lived with a sibling with ASD and how these experiences contribute to their support needs. | Phenomenological study. | Young adult siblings who lived with a sibling with ASD in Saskatchewan, Canada. | In-depth qualitative interviews using a phenomenological approach to explore participants’ experiences and perceptions regarding their relationship with a sibling with ASD. | The participants’ lived experiences revolved around two main themes: challenging experiences and positive experiences. These themes formed the essence of a “different, but no less important relationship” than other sibling relationships. | The findings suggest the need to develop specific support groups for siblings of individuals with ASD, based on a thorough understanding of their lived experiences and unique needs. | The study is limited to a specific geographic and cultural context (Saskatchewa, Canada); participants’ experiences may not be generalizable to other. populations or cultural contexts. |

| Longobardi et al., 2019 [38] | To examine parents’ perceptions of sibling relationship quality and its association with neurotypical siblings’ behavioral and emotional characteristics. | Quantitative correlational study. | 43 parents of children with ASD and neurotypical siblings. | Measurement of siblings’ emotional and behavioral difficulties, sibling personality, and sibling relationships through questionnaires completed by parents. | Behavioral difficulties such as emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/disattention, and problems in peer relationships are significantly associated with negative sibling relationships, characterized by rivalry, aggression, avoidance, and didactic behavior toward the sibling with ASD. | Sibling-focused interventions should focus on improving negative sibling relationships to reduce the impact on the neurotypical sibling’s developmental difficulties by providing skills and approaches to improve these relationships. | Small sample size, limited to a specific cultural context; results may not be generalizable to other populations. |

| Braconnier et al., 2018 [39] | To examine parents’ and siblings’ perceptions of the positive and negative behaviors exhibited by neurotypical siblings and their siblings with ASD. | Quantitative correlational study. | Neurotypical siblings of individuals with ASD and their parents. | Evaluation through self-administered questionnaires on positive and negative behaviors within the fraternal relationship, both from the perspective of parents and siblings themselves. | Neurotypical siblings tend to evaluate the sibling relationship more positively than their parents. Neurotypical siblings exhibit more positive behaviors than their siblings with ASD, but they are also frequent recipients of aggression. | The findings suggest that neurotypical siblings assume a caring role, highlighting the need for interventions that aim to support these dynamics and reduce emotional burden and conflict. | Potential bias due to differences in parents’ and siblings’ perceptions; limited sample in terms of cultural diversity and size. |

| Kryzak and Jones, 2017 [40] | Teaching social-communication and self-management skills to neurotypical siblings of children with ASD and evaluating the generalization of these skills. | Study with multiple baseline probe design among sibling dyads. | 4 Neurotypical siblings of children with ASD. | Behavioral skills training, including instruction, modeling, practice, and feedback for self-management of the social skills curriculum. Evaluation of generalization of social-communicative responses in novel contexts and over time. | Neurotypical siblings independently mastered the social skills curriculum, with some generalization of learned skills to new contexts and over time. Comparison with typical peers provided some support for the social validity of the intervention results. | The results support the use of self-management to promote generalization of social-communicative skills in neurotypical siblings, suggesting that explicit programming for generalization should be a key consideration in interventions. | Small study size with a limited number of participants, which may limit the generalizability of the results; assessment of generalization was limited to specific contexts and defined time periods. |

| Garrido, Carballo, and Garcia-Retamero, 2020 [41] | To explore the factors that influence the impact of having an older sibling with ASD on different developmental domains and family quality of life (FQoL). | Case-control study. | 78 unaffected siblings of children with ASD and children with typical development, aged 6 to 12 years. | Assessment of motor skills, severity of autistic traits, satisfaction with family quality of life (FQoL), and social support using specific questionnaires and tests. | Significant differences between groups in motor skills, severity of autistic traits, satisfaction on FQoL, and social support. Social support is a positive factor that protects against reduced satisfaction on FQoL related to having a sibling with ASD. | Social support is a critical aspect to consider in interventions to improve satisfaction on the FQoL of unaffected siblings of children with ASD, suggesting the need to monitor the development of these children over time. | Study limited to a relatively small and specific sample, which may limit generalizability of results; need for further research to explore other potential protective factors and their long-term impact. |

| Van der Merwe et al., 2017 [42] | To investigate how adolescents with typical development remember their past attitudes and describe their current attitudes toward siblings with ASD. | Cross-sectional study with quantitative approach. | 30 adolescents with typical development who have siblings with ASD in South Africa. | Participants completed the Lifespan Sibling Relationship Scale to assess sibling attitudes in three components: affect, behavior and cognition. Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests and ANOVAs were used to analyze significant differences between time periods and components of attitudes. | Participants showed more positive attitudes toward their siblings with ASD as adolescents than when they were younger. Adolescents rated their current emotions and beliefs toward siblings with ASD as more positive than their current interaction experiences. | The results suggest that sibling attitudes change over time, underscoring the importance of a lifespan approach in designing and implementing supports for siblings of children with ASD. | The study is limited to a relatively small and specific sample (adolescents in South Africa), which may limit the generalizability of the results; the cross-sectional design does not allow causality to be established. |

| Toseeb, McChesney, and Wolke, 2018 [43] | To estimate the prevalence and psychopathological correlates of sibling bullying in children with and without ASD. | Prospective study based on a population-based cohort. | 475 children with ASD and 13,702 children without ASD, age 11 years. | Analysis of data from the Millennium Cohort Study to assess the prevalence of fraternal bullying and its psychopathological correlates, including internalizing, externalizing and prosocial skills problems. | Children with ASD are more likely to be bullied by siblings than children without ASD. They are also more likely to be both victims and perpetrators of sibling bullying, which is associated with lower prosocial skills and greater internalizing and externalizing problems. | Interventions to improve social and emotional outcomes in children with ASD should focus on both affected and unaffected siblings to address bullying dynamics and promote prosocial skills. | The study is based on self-reported data, which may introduce response bias; the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to establish causality in the observed relationships. |

| Quatrosi et al., 2023 [44] | To explore the quality of life (QoL) components of non-autistic siblings of individuals with ASD through a scoping review of the literature. | Scoping review. | Non-autistic siblings of individuals with ASD. | Analysis of nine studies selected from peer-reviewed databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, ERIC) evaluating the QoL of non-autistic siblings of individuals with ASD compared with siblings of non-autistic individuals and patients with other chronic diseases. | The condition of having a sibling with ASD has varying effects on the QoL of non-autistic siblings, with reduced psychological well-being, less perceived social support, greater aggression and susceptibility to conflict, and higher levels of anxiety and stress. | The findings suggest the need to organize and improve support services for non-autistic siblings of individuals with ASD, as their needs are often underestimated and neglected. | Review limited to a small number of studies (9) and specific databases; variability in results indicates need for further research to obtain more definitive conclusions. |

| Brinkman, Barry, and Lindsey, 2023 [45] | To explore the interrelationships between symptom severity and externalizing behavior in children with ASD, parental stress, affiliated stigma, expressed emotion (EE), and internalizing behavior of neurotypical siblings (TD). | Quantitative correlational study. | Families with children with ASD and neurotypical siblings. | Analysis of relationships between family and behavioral variables by self-administered questionnaires on stress, affiliated stigma, EE, and sibling behavior. | Significant interrelationships were found between symptom severity in children with ASD and externalizing behavior, parental stress, affiliated stigma, EE, and internalizing behavior of neurotypical siblings. Some subcomponents of affiliated stigma predicted unique variance in EE and internalizing behavior of TD siblings. | The results suggest that the psychosocial functioning of neurotypical siblings is influenced by family factors such as parental stress and affiliated stigma. Interventions aimed at reducing stress and managing stigma could improve outcomes for all family members. | Limitations of the study include self-reported data, limited sample diversity, and a cross-sectional design that does not allow causality to be established. |

| Orm et al., 2021 [46] | To investigate the factor structure and convergent validity of the Negative Adjustment Scale (NAS) for measuring sibling adjustment of children with disabilities. | Psychometric validation study. | 107 siblings of children with disabilities (M age = 11.5 years, SD = 2.1). | Validation of the NAS through factor structure analysis and verification of convergent validity with a general measure of mental health. Correlations between NAS and externalizing and internalizing mental health difficulties were analyzed. | A one-factor structure was confirmed for NAS. Convergent validity was demonstrated through significant correlations (r = 0.29–0.44) with externalizing and internalizing mental health difficulties in siblings. | NAS shows promise as a tailored tool for assessing the adaptation of siblings of children with disabilities, useful for identifying difficulties and supporting targeted interventions. | The study is based on a limited and specific sample, which may not represent all populations; further studies are needed to confirm the validity and reliability of the instrument in different contexts. |

| Douglas, Bagawan, and West, 2024 [47] | To explore neurotypical (NT) siblings’ perceptions of their relationships with siblings with ASD and to develop a theory explaining the underlying family dynamics. | Qualitative meta-synthesis. | Not applicable (synthesis of existing qualitative studies). | A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies using a theory-generating approach. | The findings suggest that NT siblings’ relationships with their ASD siblings are shaped by multiple factors, including the characteristics of the ASD sibling, the family context, and NT siblings’ coping strategies. | The study highlights the need for targeted interventions to support NT siblings, improve relationship quality, and reduce stress associated with having a sibling with ASD. | The synthesis relies on existing qualitative studies, limiting generalizability; no quantitative data are analyzed. |

| Watson, Hanna, and Jones, 2021 [48] | To systematically review qualitative studies examining the experiences of NT siblings of children with ASD. | Systematic review. | 15 qualitative studies met inclusion criteria. | A systematic search across six databases, followed by thematic synthesis. | NT siblings’ experiences are shaped by self-identity, personal development, social interactions, and coping strategies. Interactions with both ASD siblings and external individuals can be both beneficial and challenging. | Emphasizes the need for interventions to support NT siblings, focusing on their coping strategies and personal development. | Limited to qualitative studies; lacks a quantitative perspective on NT siblings’ well-being. |

| McDowell, C.; Bryant, 2024 [49] | To systematically review sibling-mediated interventions (SMIs) for children with ASD. | Systematic review. | 10 studies met inclusion criteria. | Systematic literature search and synthesis of intervention characteristics, outcomes, and effectiveness. | SMIs improved reciprocal play, communication, and emotional connection between NT siblings and ASD siblings. Outcomes varied due to small sample sizes and different intervention methods. | Highlights the clinical potential of SMIs to enhance family relationships, but calls for standardization of intervention measures for greater replicability. | Small sample sizes, lack of standardized outcome measures, and limited generalizability due to participant homogeneity. |

| Mokoena and Kern, 2022 [50] | To explore the lived experiences of South African NT siblings of children with ASD, focusing on identity, emotional burden, and family dynamics. | Qualitative study (phenomenological design). | Eight university students with siblings diagnosed with ASD. | Semi-structured interviews analyzed using a five-stage interpretive phenomenological analysis approach. | NT siblings reported emotional burden, premature development, perceived unfair treatment, identity formation, and family dynamics. Despite these challenges, they also expressed efforts toward acceptance and appreciation of their sibling’s role in shaping their life paths. | The study highlights the need for structured community-based interventions and support programs to reduce stigma and stress in NT siblings, particularly in collectivist cultures. | Small sample size, limited to South African participants, which may not be generalizable to other cultural contexts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cervellione, B.; Iacolino, C.; Bottari, A.; Vona, C.; Leuzzi, M.; Presti, G. Functioning of Neurotypical Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020052

Cervellione B, Iacolino C, Bottari A, Vona C, Leuzzi M, Presti G. Functioning of Neurotypical Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(2):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020052

Chicago/Turabian StyleCervellione, Brenda, Calogero Iacolino, Alessia Bottari, Chiara Vona, Martina Leuzzi, and Giovambattista Presti. 2025. "Functioning of Neurotypical Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review" Psychiatry International 6, no. 2: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020052

APA StyleCervellione, B., Iacolino, C., Bottari, A., Vona, C., Leuzzi, M., & Presti, G. (2025). Functioning of Neurotypical Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International, 6(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020052