1. Introduction

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a multifaceted mental illness characterized by a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, affect and marked impulsivity, beginning by early adulthood and presenting in a variety of contexts [

1]. It presents with high rates of health resource use due to various crises, the most severe characterized by self-harming behavior (SHB) and suicidal ideation and attempts.

Various programs dedicated to the treatment of these patients have been implemented internationally to attempt to provide structured support and a better quality of life. In 2013, the Psychiatry Department of São João University Hospital Centre created the first Portuguese-based specialized treatment program for BPD, based on the McLean Hospital Model [

2]. It consists of a structured treatment plan based on international guidelines, with psychotherapy being the core method of intervention. Various psychotherapeutic methods have been shown to be efficacious and cost-effective in BPD, namely transference-focused therapy (TFP), schema therapy (ST), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and mentalization-based treatment (MBT), with the latter two being a specific focus of the Portuguese program.

The Portuguese program integrates four levels of care: inpatient, residential/day hospital, intensive outpatient treatment and outpatient treatment. These levels are not sequential, and patients can be admitted to the program at any level, depending on their clinical situation. Structured, coordinated and effective treatment reduces symptoms and improves quality of life, lowering both direct (related to treatment, particularly hospitalizations) and indirect costs.

From its inception in 2013, over 290 patients have been referred to this program, with many of the cases presenting with severe symptoms requiring regular monitoring and support in a multidisciplinary setting. The multidisciplinary team consists of psychiatrists, psychologists and occupational therapists, with additional support provided by nurses and residents. Treatment support is provided via individual and group modalities.

As would be expected of this disorder, which is marked by significant instability and impulsivity, the dropout rate of the program is relatively high and is a notorious problem [

3,

4,

5]. Approximately one-third of all BPD patients receiving psychotherapy do not finish treatment, and studies regarding the predictors of therapy are inconsistent [

6]. According to the literature, dropout rates, which are habitually higher in the earlier stages of treatment, typically being highest in the first quarter of treatment, are a frequent problem in those diagnosed with BPD [

7]. Dropout rates have been found to be associated with the patient’s first impression of the program, their expectations regarding treatment and their motivation for change [

4]. The literature is relatively scarce in regard to recent trends regarding dropout rates, as well as in exploring risk factors and motivations. Data exploring the significance of program design details, such as consultation intervals, as well as comparing specialized programs to general ones, are absent.

Factors such as high impulsivity and comorbidity with other mental disorders, such as eating disorders and substance use disorder, also exert a significant impact as predictors of treatment dropout [

3]. Issues such as elevated anger, difficulty in trusting others and therapeutic alliance at the beginning of treatment additionally influence dropout rates [

8,

9]. Furthermore, there can be unfavorable external circumstances, such as logistics, accessibility and organizational difficulties, as well as external pressure by third parties. A 2023 study also identified higher dysregulation as a factor for predicting premature treatment dropout [

8]. According to one review conducted by Arntz et al., treatment modalities such as schema therapy and mentalization-based treatment demonstrated the lowest dropout tendency, whereas community treatment had the highest dropout rates. Lastly, this study reported that group therapy had the highest dropout rate [

8].

A stable maintenance treatment plan is fundamental in promoting quality of life, diminishing the frequency and intensity of crisis, in addition to avoiding the inefficient use of healthcare resources and the demoralization of healthcare providers. Treatment dropout is associated with a myriad of negative therapeutic and psychosocial outcomes. It is due to this that the clarification of population characteristics and motivations underlying dropout rates are valuable. With this, a plan can be designed to diminish these elevated numbers as well as intervene in areas identified as significant, which can subsequently prevent treatment dropout.

As dropout is a frequent occurrence in this population, with important implications in terms of treatment outcomes and resource allocation, the present study aims to elucidate the modifiable factors associated with the population and with the program that might motivate dropout so as to promote the development of strategies to mitigate their impact on treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

The authors conducted a cross-sectional study, utilizing a questionnaire, with patients integrated in the specialized treatment program for Borderline Personality Disorder of a central hospital in Portugal. All patients included in the study gave informed consent to participate. Initially, contact was attempted with 37 subjects, of which 5 rejected participation and 14 did not respond. The final sample of the study included 18 participants, the vast majority of whom were female (n = 17; 94.4%) and aged between 23 and 50 years (M = 31.50; SD = 7.44). The full sociodemographic characterization of the sample can be consulted below (

Table 1).

2.1. Data Collection

A list of all patients integrated into the Borderline Personality Disorder specialized treatment program from 2014 to 2023 were compiled in an Excel file. Those who had a BPD diagnosis and had dropped out were identified and included in the study. Although a formal definition of dropout has not been defined, the authors included those patients that did not return to the program after 3 subsequent absences without previous contact as dropouts. Those who did not have a principal diagnosis of BPD and/or maintained participation in the program were discharged or transferred to other types of follow-ups, and were excluded from participation. Participants included were those with a formal diagnosis of BPD, having been initially integrated in the program with completion of the initial evaluation and with 3 non-justified subsequent absences. Those who were included would receive a phone call from one of two of the authors, in which an introductory note explaining the anonymity of participation as well as the objectives of the study was conducted. Posteriorly, the acquisition of patient consent to participate was verified. If the patient consented to participation, the questionnaire would be applied, with the researcher reading a paper-based version of the questionnaire which would be filled out in accordance with the participant’s responses. The paper-based questionnaire, developed by the authors, with a standardized script to reduce possible bias, was conducted via telephone. It had 8 questions with multiple choice, Likert scale and open-ended questions. A copy of the questionnaire items is provided as a Supplementary Material. Sociodemographic information was consulted in each participant’s medical record.

2.2. Data Management and Analysis

The data were entered into a password-protected Excel file, and IBM® SPSS® Statistics software version 29.0 was used to summarize the survey responses and apply statistical procedures. Descriptive statistical tools were utilized in this study, as well as correlations and a multiple linear regression model. Data were subjected to analysis of age, gender, civil status and academic level, as well as personal- and program-associated variables and motivators for dropout. For descriptive analysis, absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables, and means and standard deviations for quantitative variables. For the analysis of correlations between the variables under study, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used for the correlations between two quantitative variables, the point-biserial coefficient for correlations between a quantitative and a dichotomous qualitative variable and the value of phi for correlations between two dichotomous qualitative variables. To analyze the predictive value of a set of variables in the variation in the participants’ assessment of the intervention program, a multiple linear regression model was performed, checking all necessary assumptions (detailed below).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. The average age was 31.50 years (SD = 7.44), with the vast majority of participants aged between 23 and 38, which shows a relatively low dispersion of this variable, although two exceptions can be identified in participants aged 48 and 50. With regard to gender, the vast majority were female (n = 17; 94.4%), which shows a significant lack of balance in this variable, since there was only one male subject (5.6%), accentuating the lack of representativeness of this specific population.

Some lack of balance can also be identified in relation to marital status, although this is generally a less relevant characteristic. There was a large majority of single people (n = 15; 83.3%), with only two in a civil partnership (11.1%) and one being divorced (5.6%). This distribution, although unbalanced in objective terms, may be related to a tendency among the sample to remain single, regardless of whether they have a stable partner. On the other hand, it may also reflect the specific characteristics of the population in question, associated with PPB.

Demonstrating a similar pattern, the level of education leans heavily towards secondary education (n = 12; 66.7%), with only two subjects having a bachelor’s degree (11.1%) and four having a master’s degree (22.2%). This pattern seems to deviate slightly from what is expected for a population in this age group, although it may reflect, on the one hand, the fact that some of the participants (especially the younger ones) may have been attending degree courses at the time of data collection, and, on the other, the lower level of education associated with this population. Finally, the majority of participants were in active employment (n = 11; 61.1%), three were unemployed (16.7%) and four were students (22.2%).

3.2. Characterization of Current Status

To obtain information on the participants’ current status, five simple questions on the subject were included (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). On average, the subjects abandoned follow-up after 8.61 consultations (SD = 6.60), with the minimum being after 1 consultation and the maximum after 21 consultations. Looking at the median (Me = 5.50) gives a better idea of the central tendency of this variable, since the distribution of the data shows that nine participants dropped out after 5 or fewer appointments, and another nine after more than 5 appointments. In other words, although the average was close to 9 appointments (M = 8.61; SD = 6.60), half of the sample dropped out after less than 6 appointments.

Directly related to the current follow-up, eight subjects said they were receiving psychiatric follow-up (44.4%) and ten said the opposite (55.6%), indicating that around half of the sample had sought follow-up elsewhere after the dropout. Regarding psychological/psychotherapeutic follow-up, fewer subjects reported that they were currently being accompanied (n = 5; 27.8%), with the majority reporting that they were not (n = 13; 72.2%), which suggested that, after the dropout, there was a greater search for psychiatric follow-up than psychotherapeutic follow-up.

Lastly, most participants demonstrated no desire to start the program again (n = 13; 72.2%), which may have been due not only to the reasons that led to the dropout, but also to the way that they currently felt, and whether or not they were being monitored. This issue is shown in

Figure 1, where we can analyze the distribution of answers to the question “Since you chose not to attend the program, how have you been feeling?”, and it is clear that the majority of participants report an improvement after the dropout (better + much better; n = 12; 66.7%), while three say they feel no difference (neither better nor worse; 16.7%) and another three say they feel a deterioration (worse + much worse; 16.7%).

3.3. Evaluation of the Program and Reasons for Dropout

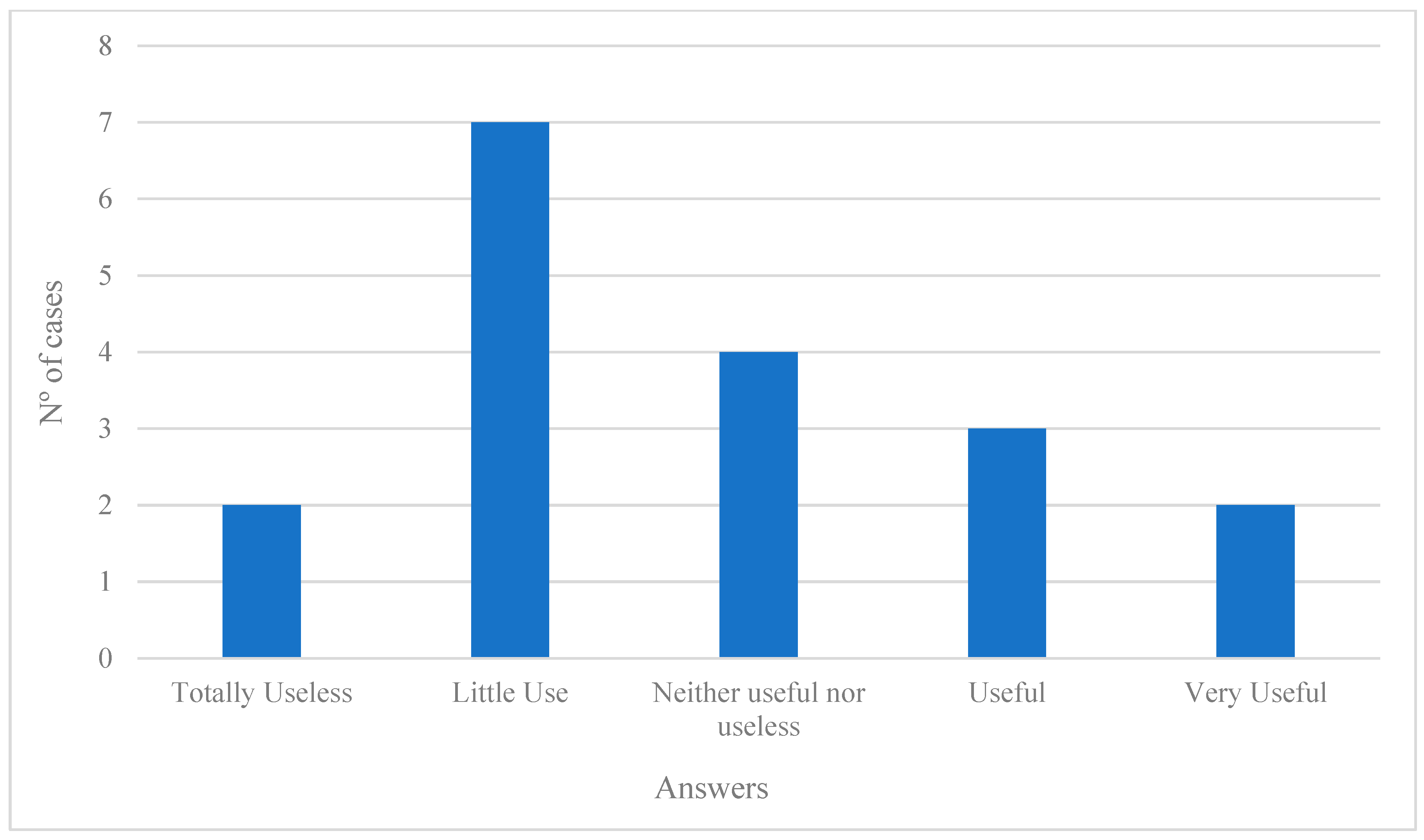

In order to frame the participants’ description of the factors related to dropout and their subjective evaluation of the intervention program, two questions were asked (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Firstly, the question “How do you rate the treatment in the Borderline Personality Disorder Intervention Program that you attended, in terms of its usefulness?” was asked, and it was possible to see that, in a similar vein to the responses shown above, the majority of the subjects found the program to be of little or no use (neither useful nor useless + not very useful + totally useless; n = 13; 72.2%), although of these participants, only two considered it to be totally useless (11.1%). On the other hand, five participants considered the program to have been of some use in their case (useful + very useful; 27.8%).

With regard to the reasons mentioned for leaving the program, these were divided into two types—reasons related to the treatment and reasons related to personal issues—with the vast majority of responses falling into the former (twenty-eight mentions in total) and only a few into the latter (eight mentions in total), with each participant being able to mention as many reasons as they wanted in each type. More specifically, it can be seen that when it comes to treatment-related reasons, four stand out as being the most mentioned: excessive spacing between appointments (n = 6; 33.3%); loss of interest/motivation (n = 5; 27.8%); dissatisfaction with treatment (n = 4; 22.2%); and not recognizing any benefit from treatment (n = 4; 22.2%). Again, there seemed to be a tendency for dropouts to be associated with dissatisfaction with the treatment and with the subjective evaluation made by the subjects. Nevertheless, three reasons related to personal issues could also be identified: overlapping hours with other responsibilities (n = 5; 27.8%); logistical difficulties (n = 2; 11.1%); and changes in life situation (n = 1; 5.6%). It is clear that, in general, participants tended to blame the program’s characteristics more than factors linked to themselves or their personal lives, which may also be associated with the pattern of subjective evaluations of the program presented above.

3.4. Correlations Between the Variables Under Study

Table 3 shows the correlation matrix between the variables of interest. To begin with, the age of the participants only correlated significantly with the number of consultations before the dropout, correlating positively and moderately (r = 0.551), indicating a tendency for older subjects to have had more consultations before leaving the program. For all of the other variables, there seemed to be no trend according to age. Similarly, the number of consultations before dropout did not correlate significantly with any other variable.

Regarding the participants’ evaluation of the treatment in the intervention program, two significant correlations can be observed: (1) with the willingness to start the follow-up again, there was a negative and moderate correlation (r = −0.537), which indicates that subjects who rated the program better tended to say that they felt more like starting it again, and vice versa; (2) and there was a negative and moderate correlation (r = −0.503) with how they felt after leaving the program, indicating that subjects who rated the program better tended to report feeling worse since leaving it, and vice versa. On the other hand, there were no significant correlations between the evaluation of the program and the current existence of psychiatric or psychotherapeutic follow-up. It should also be noted that the desire to restart follow-up and the way the subjects had felt after leaving the program did not correlate significantly with any other variable. On the one hand, the occurrence of current psychiatric or psychotherapeutic counseling did not show significant correlations with any variable, except between themselves, in a positive and strong way (phi = 0.693), indicating that people who currently had one type of counseling tended to also have the other.

3.5. Predictive Value in Treatment Evaluation Variation

So, to assess the predictive value of some of the variables studied in the variation in the participants’ evaluation of the treatment, and based on the correlations presented above, a multiple linear regression model was prepared, with the evaluation of the treatment as the dependent variable (

Table 4 and

Table 5). The following were included as predictors: number of consultations before the dropout; current psychiatric follow-up; current psychotherapeutic follow-up; willingness to start again; and how they felt after the dropout.

The assumptions for applying this procedure were tested using the graphical analysis of the residuals, the Durbin–Watson value (d = 1.938) and the VIF (all <5), and there were no problems of multi-collinearity. The regression model proved to be significant (F (5, 12) = 4.864; p < 0.012; R2a = 0.532), explaining around 53.2% of the variation in the dependent variable. Of the five predictors included, only two proved to have a significant influence on this variation, namely (1) the number of consultations before the dropout (B = 0.105; β = 0.567; t(11) = 2.932; p < 0.013), suggesting that a greater number of consultations before dropout may have led to a better evaluation of the treatment; and (2) the way the subjects had been feeling after the dropout (B = −0.692; β = −0.731; t(11) = −2.917; p < 0.013), indicating that feeling worse after the dropout may have led to a better evaluation of the treatment. Even so, it should be noted that this last relationship was likely to be characterized by bidirectional dynamics, with both variables influencing each other simultaneously.

4. Discussion

Most programs directed at treating BPD have significant rates of dropout, so much so that it is one of the motivating factors for the development of specialized psychotherapeutic approaches designed to mitigate this. This study aimed to clarify populational and modifiable factors associated with dropout rates in this population. To the authors’ knowledge, no study has evaluated this population and contrasted it with specialized program characteristics.

The population sample was taken from 2014 to 2023; the authors deemed this beneficial as it allowed for the identification of trends or shifts in dropout patterns over nearly a decade. Most of the identified dropout patients were of the female gender, which correlates to epidemiological studies identifying the prevalence of BPD as predominately affecting females; therefore, this finding is not surprising. The average age of the patient accompanied in the treatment plan that was subsequently abandoned was 31.50 years old. This age bracket could be unexpected, considering that this personality disorder is typically associated with a younger cohort. A possible explanation for this could be due to the sample size and characteristics of those who responded taking into consideration that more than half of the original sample was excluded due to non-participation. Another possible explanation could be that this age cohort demonstrated less severe clinical manifestations with less recognition of the potential personal benefits of such a specialized program. It is important to note that this cohort also coincides with a population which is frequently active in society, either through work or through the continuation of studies, which might serve as a possible explanation for a propensity to drop out, allied with the inherent structural difficulties of the disorder. Most of the cohort studied were single, reflecting the populational tendency of the age demographic. The literature tends to demonstrate that the influence of sociodemographic factors in treatment dropout is insignificant, with psychological factors having a more important role [

10].

Almost half of the group studied were, at the time of the interview, accompanied in psychiatric and/or psychological settings. This could be a motivating factor for the predominant evaluations of “little use and neither useful nor useless” regarding the question “How do you evaluate the treatment in the Intervention Program for Borderline Personality Disorder that you frequented in terms of usefulness?”.

The underlying motivations identified by the patients were namely the large interval between consultations, loss of interest/motivation, dissatisfaction with the treatment and non-recognition of the benefits of the treatment. These results are in keeping with those previously demonstrated in the literature [

3,

4,

5,

8]. In terms of external factors, logistic factors such as consultation overlap with other life commitments and difficulties in transport were identified. Taking into consideration that many participants in the sample were employed at the time of the study, consideration should be given to the socioeconomic context of the patients and the way this could influence treatment completion, namely in terms of external influencing factors, such as transportation, schedule overlap and other logistical problems.

In terms of clinical implications, one of the findings identified and paralleled in the research is that most dropouts take place in the early treatment phase. Our study reflects this; however, the characteristics of the program should be considered when considering this finding. Between initial evaluation, which typically comprises two to three psychiatric consultations along with psychometric evaluation by psychologists, an average of about 4 months can pass before complete integration in the program. As this period serves as an evaluation of the adequacy of integrating into the program and directed intervention is not the objective, patients could feel frustration and drop out before the therapeutic alliance is solidified and directed intervention is implemented.

It is fundamental to invest in factors that can promote treatment engagement and compliance in this phase. However, further studies are needed to identify why this period of treatment is so subjected to dropout as well as to develop methods to ensure involvement during this phase. It could prove beneficial to distinguish trait- and state-like components influencing the quality of the therapeutic alliance, as this was a complaint brought up by some of the sample [

11]. One method suggested in the literature to improve treatment adhesion is through the regular monitoring of the therapeutic alliance [

7]. Professionals working with BPD patients stand to benefit from optimizing emotional regulation and distress tolerance strategies earlier in treatment to reduce premature dropout [

9].

The results of the questionnaire could reflect the inherent traits and defense mechanisms typically demonstrated in BPD, such as a dichotomic view of others with a tendency to utilize splitting, as well as a tendency to evaluate others as untrustworthy or hostile [

12]. In addition to these traits, those with BPD tend to demonstrate an external locus of control with emotional regulation and evaluation of internal and external events [

13]. These traits could amplify a tendency to feel negative evaluations not only towards treatment plans but also towards therapists when evaluated retrospectively, thus explaining the results of this study.

Limitations of This Study

Our study had a relatively small sample size, and the results should be viewed in that light, namely in terms of the limited representativeness of the sample with the possible exclusion of certain perspectives and other relevant dropout motivators. Although the generalization of these results can be challenging due to this limitation, these results shed light on factors not typically explored in the available literature, thus offering the potential for larger studies with a robust sample size.

In addition, a non-validated questionnaire was utilized, which can pose limitations on the consistency and accuracy of the reported results. Moreover, the survey utilized mostly included closed-ended questions; thus, detailed data on participant perspectives may have been occluded. Although open-ended questions were included, many participants opted not to elaborate on these questions, possibly due to fatigue or due to the impersonal and distant nature of contact via telephone. Admittedly, some of the parameters analyzed in the questionnaire could be restructured so as not to induce ambiguity, namely, the differentiation between indifference and mixed feelings in those who responded in a neutral sense. In those who provided multiple responses, a more structured analysis into primary and secondary reasons could be carried out. Improvements could also be made in terms of statistical exploration by subgroup analysis in terms of age, for example. Additional questions regarding therapeutic alliance and perceived stigma could also be relevant in future inquiries.

A further exploration of demographic and clinical characteristics could have been added to the questionnaire so to as to produce a more robust and clearer picture of the population in question, such as family status, previous/active substance use, other comorbid medical and/or psychiatric states and previous therapeutic interventions. Qualitative research is needed to better understand the underlying motivators and risk factors for treatment dropout, for example, through structured interviews and larger scale statistical analysis with validated questionnaires. It may prove beneficial to carry out future studies with diverse populations and multiple sites to improve the applicability to groups.