Abstract

Nature-based interventions (NBIs) grounded in mindfulness have been shown to be beneficial for improving mental wellbeing in adults. With increasing mental health challenges among children and adolescents, accessible and cost-effective interventions are essential to enhance their well-being. Brief mindfulness-based NBIs may be helpful in this regard, but there is a dearth of evidence testing such NBIs in young adolescents. The aim of this study was to test the effect of a brief nature-based meditation on mental wellbeing in community groups of adolescents (n = 38; aged 12–17) and adults (n = 39; aged 18–26). We hypothesised that the meditation would reduce depressive rumination and stress in both age groups. In a repeated-measures design, participants completed self-report measures, indexing mental wellbeing (state rumination and stress) before and immediately after listening to a brief (13 min) nature-based meditation. Rumination and stress improved overall, and the pattern in the data suggested that effects were larger for adults when compared to adolescents. This study provides preliminary evidence for the use of a brief nature-based meditation in improving mental wellbeing in adolescents. Future research should make NBIs age appropriate and examine their effectiveness for clinical adolescent populations.

1. Introduction

1.1. Adolescence

Half of mental disorders begin before age 14 [1], with around three quarters evident by the mid 20s [2,3]. The peak age of onset is 14.5, with a high onset of mood disorders specifically in late adolescence [3]. In addition, rates of mental disorders are rising in adolescents and young adults [4,5]. For example, research suggests that five times as many students reported mental health conditions in 2017 than in 2007 [6]. Furthermore, in non-clinical populations, adolescents report higher academic stress than previously, resulting in poor mental health outcomes [7].

Improving mental health and preventing the onset or recurrence of mood disorders is therefore a priority for adolescents to alleviate suffering and help lessen the pressure on struggling mental health services [8,9,10]. One approach to address this is through early preventative strategies for children and young people [11]. As early onset of a disorder is associated with worse mental health outcomes [12,13], this focus could help reduce the lifetime prevalence of psychopathologies and improve wellbeing throughout the lifespan.

For these reasons, interventions for the prevention of mental health difficulties in adolescents are of paramount importance, and one area that has shown potential is contact and connection to natural environments, which are thought to facilitate good health and wellbeing [14]. For example, research indicates that greater access to green spaces in childhood correlates with a reduced risk of long-term mental health disorders [15], and spending more time outdoors predicts better health and wellbeing [16,17,18,19].

1.2. Nature-Based Interventions and Adolescent Mental Health

Nature-based interventions (NBI) may promote two beneficial mental wellbeing pathways: a “buffering against harm pathway” and a “promotion of positive pathway” [17]. Both are likely to be helpful for adolescent wellbeing [17]. Classic psychoevolutionary theories on nature and wellbeing include attention restoration theory (ART) [18,19], which suggests that natural environments facilitate the restoration of limited direct attentional resources; and stress reduction theory (SRT) [20], which posits that natural—as opposed to urban—environments reduce psychological and physiological stress. Nature-mediated stress reduction has subsequently been supported by psychophysiological evidence [21].

NBIs in younger populations, however, are under-researched, and there is a dearth of data comparing the effects of NBIs on mental wellbeing in adolescents and young adults. In addition to the growing concern around recent increases in adolescent mental health difficulties, adolescence is an age characterised by multiple changes, including cognitive, emotional, physiological and social and these increase mental health vulnerability [5,22]. Adolescence also represents a critical turning point in the development of emotion regulation, and for some individuals, poor emotional regulation can signal the emergence of psychopathology [23,24]. Behavioural evidence also suggests that development in adolescence results in greater emotional reactivity [25], and adolescents are especially vulnerable to the psychological and physiological effects of stress [26,27]. Chronic stress can result in stress-related hormones altering brain development and increasing the risk of mental health problems [28,29], and high stress levels in adolescence are associated with higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [30].

Moreover, maladaptive emotional regulation strategies begin to be used in adolescence [31], including rumination, the strategy of passively and repeatedly dwelling on the cause, consequences, and symptoms of distress [32]. When persistent, rumination is predictive of several mental health problems, especially depression [33,34]. It is important to note that these issues are interlinked; high stress levels are predictive of greater negative cognitive and emotional responses, especially in those with higher levels of rumination [35]. Reducing stress and rumination is therefore likely to help buffer against harm [36]. As stress impedes cognitive processes such as attentional switching [37,38], the positive effects predicted by SRT and ART may work in tandem; that is, stress reduction improves attention, supporting the reduction of rumination. Evidence from eye tracking studies has demonstrated that an inability to redirect attention characterises rumination in adolescents [39]. NBIs may therefore reduce rumination by replenishing attentional resources.

Nature exposure in adults improves somatic and mental health, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, stress, and depressogenic rumination [36,40,41], and many NBIs designed to improve wellbeing, including forest bathing, incorporate elements of mindfulness [42,43,44]. Mindfulness is the practice of paying attention intentionally and non-judgementally to the present moment [45]. While mindfulness-based interventions are themselves effective at producing positive psychological outcomes, alleviating symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety and treating psychopathologies [46,47], their effects in nature may be superior [48,49]. A systematic review found that despite the differences among NBIs utilising mindfulness, such interventions reliably produce positive effects on psychological outcomes [49].

In adults, mindfulness-based NBIs are effective at improving mental wellbeing [48]. For example, Nisbet et al. [50] found that participants walking outdoors had increased positive affect compared to those walking indoors, and that participants walking outdoors with previous mindfulness instruction reported a decrease in negative affect compared to participants without instruction. Furthermore, Jung et al. [51] found that forest meditation significantly improved self-reported stress levels compared to a control group, and Corazon et al. [52] found that a nature-based mindfulness therapy programme was as effective at lowering stress in a highly stressed population as a previously validated stress therapy. A recent study [53] compared the effects of a nature-based meditation and an indoor meditation relative to an attentional control group at improving mental wellbeing. Similarly, nature-based meditation improved mental wellbeing in adults when compared with nature-based guided imagery [54]. The results of these studies suggest that nature-based meditation for young adults may be helpful in reducing depressive rumination and stress.

Research suggests that nature exposure has a positive impact on children’s wellbeing [55], mood, memory, and attention [56], and evidence also suggests that mindfulness interventions improve adolescents’ psychopathological mood symptoms, distress levels, self-esteem, emotional regulation, stress resilience, and attention levels [57,58,59,60]. However, research on NBIs underpinned by mindfulness in younger populations is lacking.

Developmental differences may affect adolescents’ engagement with meditation, perhaps primarily because learning mindfulness skills for the first time requires attentional effort [61], which could further prevent engagement. Shortened practices may better support adolescent’s developmental stage [57], and it may be that nature can alleviate this effort. For example, Lymeus et al. [61] compared a group that learned meditation skills indoors with a group learning in nature over five weeks. The nature group in that study demonstrated consistently improving attention, while the indoor group’s initial improvements decreased over the weeks. It is likely that adolescents will benefit from a developmentally adapted nature-based meditation, and NBIs could prove to be accessible and affordable ways of promoting mental health in schools (e.g., via mental health in schools teams) and universities (e.g., via wellbeing services).

1.3. Current Study

This study compared the effect of a nature-based meditation on rumination and stress in two age-groups that are especially vulnerable to developing mental disorders: adolescents [62] and young adults [63]. The meditation used in this study has been shown to be effective in reducing rumination in young adults when compared with an attentional control [53]. We hypothesised that the nature-based meditation would improve both aspects of mental wellbeing (reducing rumination and stress). We did not expect any difference between groups in this study, hypothesising that the intervention would work equally well for adolescents as it would for adults.

2. Materials and Methods

Seventy-seven participants (school students, scouts, university students, and individuals) were recruited from the community via word of mouth and social media (see Table 1 for demographic information). The younger group (n = 38) was aged 12–17 (mean = 16.16; SD = 1.4), and the older group (n = 39) was aged 18–26 (mean = 23.31; SD = 2.2). Participants aged 16 and over were directed to information sheets and provided informed consent before participation. Those under 16 years old signed informed assent forms, and informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians. All participants were informed of their right to leave the study at any time.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

This study was reviewed and approved by an Ethics Committee. Participants were entered into a cash prize draw as a token of thanks for their participation.

2.1. Sample Size

This study was powered (G*Power, 3.1) to detect a change in the brief state rumination index (BSRI) following the meditation. We drew on previous research [53] that examined the effect of a nature-based meditation on wellbeing in three conditions (nature-based, indoors, and control). In that study, a significant reduction in rumination (as measured by the BSRI) was reported in the nature group (Cohen’s d = 0.54) as compared with the control group (Cohen’s d = 0.11). To have 90% power to detect a similar effect in the present study, thirty-nine participants per group were needed. A total of 79 participants were recruited into the study. Data for two participants were excluded due to study completion errors and missing data. A total of 77 observations (38 adolescents, 39 adults) were retained.

2.2. Psychoeducation

Brief psychoeducation was given to ensure all participants understood the basic principles of mindfulness before listening to the meditation, regardless of prior experience and to enhance the intervention efficacy [64,65]. A one-minute introduction to mindfulness video was tested with a 13-year-old to ensure it was comprehensible for the younger participants. In simple language, the video explains how mindfulness encourages people to pay attention to the present moment, using all five senses; and how mindfulness practice can improve mental health. The video was entitled “What is Mindfulness?” and produced by “Smiling Mind”.

2.3. Meditation

A nature-based meditation (see Appendix A for the full script) was adapted from a previous study [53] and overseen by a clinical psychologist. To accommodate younger participants, the script was condensed and the language was simplified. Consistent with guidelines for children and adolescents that suggest this group can benefit from meditation practice of at least 10 min [66], the final meditation recording was 13 min long. We conducted the meditation in small groups with adolescents for both feasibility and as an attempt to increase engagement with the meditation [66].

The meditation is informed by the mindfulness principles of paying attention non-judgementally to the present moment [67] and deep breathing techniques adapted from compassion-focused therapy [68,69]. Participants are encouraged to engage all their senses to take note of their surroundings. Mental imagery is used throughout to strengthen the meditator’s connection to nature [70], such as “imagine yourself tall like a tree”. Participants listened to the meditation in parks or green spaces with grass and trees to enhance the experience.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Brief Rumination State Inventory (BSRI)

The BSRI measures state rumination, with 8 items such as “right now, I wonder why I react the way I do”. Items are answered on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 (completely disagree) to 100 (completely agree), with higher scores indicating greater rumination. The scale was tested with an adult population but has since been successfully administered to young people [71]. The BSRI has good internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) and is psychometrically valid [72]. In this study, Cronbach’s α was acceptable (0.87 at T0 and 0.81 at T1 for the younger group; and 0.80 at T0 and 0.87 at T1 for the older group).

2.4.2. Stress

Participants indicate on a VAS how strongly they agree with the statement “I am stressed right now” from 0 (completely disagree) to 100 (completely agree). VAS scales are a commonly used, reliable way of measuring dynamic subjective states [73] and are psychometrically comparable to Likert scales [74].

2.5. Design

All participants completed the state inventories (BSRI and stress VAS). They watched the introduction to mindfulness video and then went outside to an area near trees where they listened to the guided meditation using their own ear/headphones. Adults completed the meditation individually and adolescents completed the meditation in groups of between four and five. Afterwards, (T1) participants completed the state inventories again. They were then fully debriefed and thanked for their time.

2.6. Analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) was used to measure the effect of time (from T0 to T1) on the outcome measures (rumination and stress). These effects were compared between groups (i.e., adolescents and adults) using Group x Time interactions. A significant interaction would suggest that the change in rumination or stress from T0 to T1 (pre to post intervention) was significantly different between adolescents and adults. We report Cohen’s d in the results as a measure of effect size. We follow the convention of interpreting Cohen’s d values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 as representing small, medium, and large effects, respectively [75].

3. Results

3.1. Manipulation Check

We first carried out a manipulation check to test whether the groups were significantly different in age. The adult group (mean = 23.3 years; SD = 2.2) was significantly older than the adolescent group (mean = 16.2 years; SD = 1.4; t(75) = −16.87, p < 0.001). A summary of the results from the RMANOVAs is presented in Table 2, along with Cohen’s d as an additional effect size.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes on outcomes by group.

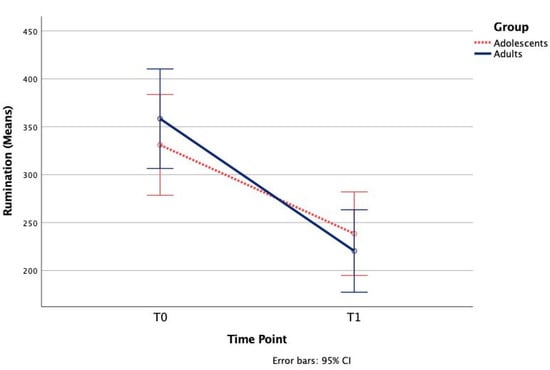

3.2. Rumination

There was a significant main effect of time on rumination (F(1,75) = 52.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.41), suggesting a change in rumination from T0 to T1 for the whole sample. As illustrated in Figure 1, rumination decreased from T0 (adolescents mean = 331.05; SD = 180.11; 95%CI = 271.85 to 390.25; adults mean = 358.44; SD = 143.71; 95%CI = 311.85 to 405.02) to T1 (adolescents mean = 238.50; SD = 141.77; 95%CI = 191.90 to 285.10; adults mean = 220.44; SD = 127.84; 95%CI = 178.99 to 261.88). There was no significant group x time interaction (F(1,75) = 2.04, p = 0.157, ηp2 = 0.03), which suggests that there was no difference between the age groups in the size of the reduction in depressogenic rumination from T0 to T1.

Figure 1.

Mean changes in rumination following the meditation.

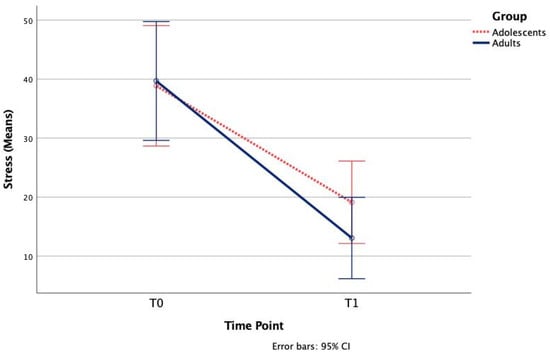

3.3. Stress

There was a significant main effect of time on stress (F(1,75) = 57.58, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.43), suggesting a change in stress over time in the whole sample. There was no significant group x time interaction (F(1,75) = 1.27, p = 0.264, ηp2 = 0.02). As shown in Figure 2, stress decreased from T0 (adolescents mean = 38.87; SD = 31.92; 95%CI = 28.38 to 49.36; adults mean = 39.69; SD = 31.22; 95%CI = 29.57 to 49.81) to T1 (adolescents mean = 19.13; SD = 25.04; 95%CI = 10.90 to 27.36; adults mean = 13.08; SD = 17.65; 95%CI = 7.36 to 18.80), which shows that the decrease in stress over time was not significantly different for the two age groups.

Figure 2.

Mean changes in stress following the meditation.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine if a nature-based meditation would be effective at reducing rumination and stress for adolescents as well as young adults. The findings are broadly consistent with predictions of improved mental wellbeing following the meditation. However, there were differences in the size of the effect on the outcome measures by age group. The effect sizes were larger in the adult group compared to the adolescent group on both outcomes of rumination and stress.

4.1. Rumination and Stress

The medium-to-large effect sizes on rumination reported here are consistent with those found in previous research [53]. Studies indicate that mindfulness training significantly reduces depressive rumination [76], outperforming distraction techniques in this regard [77]. This could be explained by employing non-judgemental self-awareness as opposed to engaging in pathological self-focus [78]. In this way, noticing and accepting internal and external sensations, as well as momentary experience, may confer psychological benefits [60,79].

ART suggests attentional restoration [18] as the mechanism behind this reduction in rumination. In adolescence, rumination is characterised by attentional control deficit, specifically delayed attentional shifting [39]. Additionally, impaired attentional control worsens stress reactivity in teenage girls [80] and predicts high negative and low positive affect [81].

The stress reduction found in the present study may be a function of both mindfulness and nature exposure. While it has been shown that mindfulness interventions alone improve self-reported measures of stress, but not physiological ones [82], nature exposure may improve both [21]. However, forest bathing, which combines both nature exposure and mindfulness, has been shown to consistently reduce cortisol levels in adults [83]. Future research should also test for physiological benefits of brief NBIs in adolescents and children.

Stress reduction itself may contribute to attentional restoration as stress disrupts attentional control by impairing the functions of the prefrontal cortex [37,38]. This impaired cognitive control can then heighten rumination in response to stressful events [84,85], and increased rumination can, cyclically, contribute to cognitive impairment in depressed patients [86]. Stress reduction and attention restoration may therefore mediate rumination reduction.

These results concur with findings in adult populations; that is, that mindfulness NBIs are generally effective at improving mental wellbeing and the magnitude of effect size is likely to be medium [49]. The results replicate previous research findings showing immediate improvements in rumination following nature-based meditation that are superior to attentional control [53] and are consistent with research demonstrating the efficacy of mindfulness NBIs for improving stress [51,52,83]. Research with adolescent populations has previously demonstrated benefits of passive nature exposure on memory, attention, and mood [56], as well as mental health and wellbeing [55]. Additionally, research has demonstrated the efficacy of mindfulness interventions on psychopathological symptoms in adolescents [60]; however, few studies compare mindfulness interventions across age groups [87], and none, to our knowledge, have investigated mindfulness NBIs in this way with adolescents. The present findings therefore offer a novel contribution to this area of research.

While adolescence can be considered a developmentally appropriate age to learn mindfulness skills [60], Peskin and Wells-Jopling [88] suggest that when provided with mental scaffolding, even younger individuals can engage in tasks that require symbolic thinking. Indeed, children as young as seven have been found to benefit from mindfulness [89], and those as young as four benefit from nature exposure [90]. Additionally, qualitative research [91] has shown that pre-adolescent children (aged 7–11) find mindfulness-based activities in nature to have a calming and relaxing effect, transcending their daily routines. However, it may be the case that attention regulation was poorer in the adolescent group as evidence suggests that attention regulation develops during the adolescent period [92,93]. The present study contributes to an understanding of how nature and meditation can be combined beneficially in young people, but even younger children could potentially benefit from an adapted and shorter version of this intervention [94].

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

This study is novel in terms of testing a nature-based meditation on adolescents and in its comparison of an intervention across age groups [87]. It was sufficiently powered and tested several key mental wellbeing indices, using valid and reliable measures. This study would, however, benefit from replication and extension. For example, more research is needed to determine the longer-term effects and acceptability of nature-based meditations on adolescents. We also note that greater validity could have been attained by the inclusion of physiological measures to corroborate the self-report measures. For example, cortisol as a measure of stress has been shown to reduce reliably following NBIs [83] and elevated cortisol may be a biomarker for depression [29]. Indeed, hyperactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis during depression is one of the most reliable findings in biological psychiatry [95].

Given that effect sizes for the older group were larger than those in the younger group, it is entirely possible that in a larger sample, group differences could become more apparent. Although the present sample size was reasonable, it might be that this study was underpowered to detect interaction effects. Certainly, the pattern in the data suggests that the effect of meditation on wellbeing was stronger in the adult group. It may be that these differences become clearer in a future study using a larger sample.

In this case, the development of more targeted approaches that take individual differences, including age into account, would be recommended. For example, although it is unclear how long effective meditation practices need to be, it has been suggested that adolescents can engage in meditation for at least 10 min [66]. However, it might be that a training phase is needed for younger people, or repeat practice, to enhance the beneficial effects. Alternatively shorter meditations could be tested, or meditations that are grounded within the body, for example “starfish” (using your hand) or “soles of the feet” practices.

Moreover, any replication studies should systematically compare solitary versus group nature meditation to confirm if this was the cause of the different effect sizes found here. It has been suggested that group mindfulness can be helpful for children and young people by instilling a sense of group camaraderie, but this may depend on how engaging the practice is perceived [66]. Further research should therefore test whether a more engaging nature-based intervention package would be more appropriate for children and adolescents.

Including more relevant outcome measures, such as emotional regulation [96], may identify other likely key ingredients in explaining the benefits of NBIs and would support mechanistic research and theory development. Further studies should systematically test the meditation alone versus in groups to assess potential negative group effects, including self-consciousness. Clearly if such effects exist, individual administration should result in greater wellbeing benefits. A practical limitation of the present study should also be noted. First, green spaces and weather varied. While it was beyond the scope of the present undertaking to record ambient conditions, future research should continue to aim to standardise and measure green natural environment spaces as much as possible. We also recognise that there are many unmeasured variables in the present study that may have influenced the outcomes. For example, sleep deprivation is a possible cause, especially as this study was carried out soon after exam time at the end of term. Sleep deprivation can worsen mood, emotional regulation, and mindfulness [97,98] and is common in adolescence due to circadian rhythm changes, school hours, and social demands [99]. Similarly, it has been established that early adversity [100] and stressful life events increase the risk of mental disorders such as depression [101]. It is therefore entirely possible that these factors and other individual differences such as temperament [102] may influence the effect of NBIs on psychopathology-related outcomes such as reported stress and rumination.

4.3. Clinical Implications

The current study provides evidence that a nature-based meditation is an appropriate intervention for improving facets of mental wellbeing in adolescents, as it is for young adults. The present study demonstrated effectiveness at reducing stress and state rumination. These are beneficial outcomes for people in general, but especially for modern adolescents, who arguably experience higher stress levels [7] and growing numbers of psychopathologies [4,6]. While the primary aim was to investigate the effects of a brief NBI in a community population, future research should examine whether the present intervention is equally effective in clinical adolescent populations.

Improving rumination and reducing stress in younger populations may help mitigate the development and severity of mental health conditions like depression. Given the accessibility and affordability of interventions like the meditation used in this study, schools and universities could consider using similar NBIs to improve student mental health [61] and, as a secondary benefit, improve their nature connectedness [103]. For younger pupils, Forest Schools lend themselves well to including mindfulness NBI activities, facilitating children to explore nature with all their senses [104]. Implementing such NBIs in educational settings should be carefully thought out however, as recent evidence on a universal approach to mindfulness in schools suggests no benefit in preventing depression or improving social–emotional–behavioural functioning or wellbeing when compared to teaching as usual [93]. Consideration of targeted versus universal approaches to implementing NBIs should therefore be considered. This may help us to better understand what works for whom. Child and adolescent mental health services may implement these kinds of interventions in relapse prevention packages or as adjuncts to other therapies. They can be easily demonstrated in session, taught with family members or carers present to help support home practice, and can be recorded for ease of use in outside-of-clinic settings. Given accessibility to devices, audio recordings of NBIs can be listened to on mobile phones discreetly through earphones, supporting engagement of home practice. NBIs may also support early connection to and development of mindfulness practice skills, which can be drawn upon into and throughout adulthood.

4.4. Future Directions

It is important that research continues to investigate interventions across different ages. The earlier interventions are started, the greater their long-term outcomes [11], so future work with younger groups is recommended. Areas that may be fertile include investigating how best to build mental scaffolding to help younger children understand mindfulness NBIs [88] and determining whether age-appropriate NBIs are effective for them [94]. The so-called “positive pathway” is often a neglected priority in Western mindfulness practice [105] and depression treatments [106]; it often takes second place to the “buffering against harm” pathway [17]. However, the parallel promotion of a positive pathway is equally important. Positive affect reduces as adolescents age [107], but by fostering opportunities for positive affect, interventions can improve stress resilience [108], increase physiological recovery speed after distress [109], decrease symptoms of anhedonia [110], and help reduce suicidal behaviours in adolescents and adults [106]. Promotion of a positive pathway is especially important for adolescents at risk of developing depression, who are more likely than other age-groups to suffer from symptoms of anhedonia and suicidality [111]. Finally, more work on the development of nature-based self-help interventions would be good to see in the future to offer alternative, low stigma approaches to mental health promotion for those young people who have a preference for both nature and self-reliance.

5. Conclusions

This study provides good evidence that a brief nature-based meditation is effective in improving wellbeing in adolescents and young adults. Overall, these results are consistent with previous findings and contribute to a growing body of research supporting the efficacy of mindfulness-based NBIs.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Exeter (protocol code 1344143 and 8 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VAS | Visual analogue scale |

| BSRI | Brief state rumination inventory |

| NBI | Nature-based intervention |

Appendix A

Nature-Based Meditation Script

The subtitles (in bold) were not read aloud.

Introduction

Find somewhere comfortable to sit, stand or lean. I am going to guide you through a short meditation first, before we move anywhere, and then I will guide you on a walking meditation. Do your best to pay attention all the way through the meditation, listening to the words as I say them. If you notice yourself becoming distracted, that’s absolutely fine. Just notice what you started thinking about, then try to let go of that thought or whatever took your mind away. Try as best you can to avoid judging or labelling any thoughts you have as we go through, just notice them as they are, here, today, no right or wrong. Then focus your attention back to my voice and the meditation.

Now take a few moments to move around a little, and get as comfortable as you can, and we’ll begin the first short meditation.

Grounding

First, close your eyes, or lower your gaze so that you’re looking down. Place both feet flat on the floor if this feels ok in your body. Become aware of the ground beneath your feet. Feel your connection to the earth, allowing yourself to become really rooted, like the trees around you. Imagine yourself tall like a tree, swaying gently in the wind. If you are standing, keep a slight bend or softness in your knees.

And now just notice how you are breathing. Noticing the flow of your breath coming into the body, and out, just like the ebb and flow of the tide, always going in, and then out. Not trying to change or alter your breath, just noticing and observing how it feels to be breathing right now.

It might feel fast, or slow, shallow or deep. Perhaps you don’t notice anything at all. All of this is ok. Keep observing the breath.

And now we’re going to take some deeper breaths. In a moment, take a nice full deep breath in, and breathe out slowly. A full deep breath in, and slowly letting it go. Once more, a full deep breath in, and slowly letting it go.

And just allowing the breath to return to normal. Noticing how it feels in your body. How you feel to be in this space, connected to your breath, connected to the earth.

Ok, now begin to notice the sounds of nature around you. Start to pay attention to what you can hear. Maybe you can hear the sound of birds, or other wildlife. Maybe you can hear sounds of the weather, like the wind rustling through leaves or rain pattering down.

Ok. If your eyes are closed, gently open them. We are going to go for a guided walk.

Guided walk

Find a space away from others and begin by mindfully walking. Take your time and slow down the pace. Feeling the air on your face, and the light on your skin. Slow down the pace even more. Notice how it feels to walk in this way. How does the ground feel below your feet? Beneath each toe? Perhaps the grass is springy, or the path is stony. Perhaps the leaves are soft underfoot.

Start to notice what you can see around you. What are your eyes drawn to? What colours can you see in nature? Look down to the ground beneath you. What shapes do you notice? Think about how the earth is always there, supporting you.

Find something you are drawn to. It might be a tree, a plant, or a flower. Or something else. And pause for a moment. Spend some time really looking at it. Look closely at the colour, the intensity of the colour. The patterns that you can see. Maybe there are raindrops on it. Perhaps if you are able to, touching it and finding out its texture. Becoming really aware of the sensation of it on your skin. Lean in, using your sense of smell, perhaps cupping your hands around leaves or breathing deeply into the bark. What do you notice when you inhale? What thoughts and feelings come to mind? What sensations do you feel in your body?

And now letting that go, and continuing on with your slow and mindful walking. Try walking even more slowly as you notice your surroundings. Take a deep breath in, and slowly let it go. Notice how it smells to be outside. What the air feels like. And tuning in again to the sounds of nature around you. What can you hear?

When you are ready, take another pause. Allowing yourself to feel rooted in the ground. Now, look up. What do you notice above you? Perhaps leaves of a tree, or clouds moving through the sky. Notice how close or far away they feel. What feelings or thoughts come to you, looking at the space above?

And letting that go, continue on with your slow and mindful walking, starting to return back to where you began the meditation. Inhale deeply, exhale slowly, noticing the smell of the outdoors. Noticing new sights around you, and gentle movements in the plants and trees. Noticing anything you can feel in your body.

And when you’re ready, make your way back to where you started, sitting back down or stand in the same place. Take a moment to make yourself as comfortable as you can.

Grounding to close

Take a deep breath, and close or lower your eyes like you did before. Place both feet flat on the floor if this feels ok in your body. Feel your connection to the earth, and allow yourself to become really rooted, like the trees around you. Imagine yourself tall like a tree, swaying gently in the wind. If you are standing, keep a slight bend or softness in your knees.

Connect with your breath again. Following it all the way in, and all the way out again. Tune into the sounds around you. Gently flutter the eyelids open if you have your eyes shut. Notice the nature around you. What can you see? What are you drawn to?

We’re coming to the end of the meditation. Take a moment, just to hold this experience of sights, sounds, ground underfoot and breath. Holding your connection to everything around you.

References

- Jones, P.B. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, s5–s10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; de Pablo, G.S.; Shin, J.I.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapar, A.; Thapar, A.; Thapar, A.; Eyre, O.; Eyre, O.; Eyre, O.; Patel, V.; Patel, V.; Patel, V.; Brent, D.; et al. Depression in young people. Lancet 2022, 400, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Elvidge, H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ 2018, 361, k2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Hetrick, S.E.; Parker, A.G. The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, D.; Sweeny, K.; Sheehan, P.; Rasmussen, B.; Smit, F.; Cuijpers, P.; Saxena, S. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubicka, B.; Bullock, T. Mental health services for children fail to meet soaring demand. BMJ 2017, 358, j4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Correll, C.U.; Arango, C.; Berk, M.; Patel, V.; Ioannidis, J.P. Preventive psychiatry: A blueprint for improving the mental health of young people. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weare, K.; Nind, M. Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: What does the evidence say? Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, i29–i69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Boden, J.M.; Horwood, L.J. Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 191, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henken, H.; Kupka, R.; Draisma, S.; Lobbestael, J.; Berg, K.v.D.; Demacker, S.; Regeer, E. A cognitive behavioural group therapy for bipolar disorder using daily mood monitoring. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2020, 48, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, 903–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engemann, K.; Pedersen, C.B.; Arge, L.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Mortensen, P.B.; Svenning, J.-C. Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5188–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Olvera-Alvarez, H.A.; Gross, J.J. The affective benefits of nature exposure. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2021, 15, e12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Meditation, Restoration, and the Management of Mental Fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 480–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Q. The effect of exposure to the natural environment on stress reduction: A meta-analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.; Jones, R.M.; Levita, L.; Libby, V.; Pattwell, S.S.; Ruberry, E.J.; Soliman, F.; Somerville, L.H. The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010, 52, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvers, J.A. Adolescence as a pivotal period for emotion regulation development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, J.S.; Siegle, G.J.; Whalen, D.J.; Ostapenko, L.J.; Ladouceur, C.D.; Dahl, R.E. Pubertal changes in emotional information processing: Pupillary, behavioral, and subjective evidence during emotional word identification. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, R.D. The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 22, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, L.R.; Foster, E.; Papandonatos, G.D.; Handwerger, K.; Granger, D.A.; Kivlighan, K.T.; Niaura, R. Stress response and the adolescent transition: Performance versus peer rejection stressors. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.L.; Teicher, M.H. Stress, sensitive periods and maturational events in adolescent depression. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, M.; Herbert, J.; Jones, P.B.; Sahakian, B.J.; Wilkinson, P.O.; Dunn, V.J.; Croudace, T.J.; Goodyer, I.M. Elevated morning cortisol is a stratified population-level biomarker for major depression in boys only with high depressive symptoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3638–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, K.E.; Green, K.L.; Pettit, J.W.; Monteith, L.L.; Garza, M.J.; Venta, A. Problem solving moderates the effects of life event stress and chronic stress on suicidal behaviors in adolescence. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topper, M.; Emmelkamp, P.M.; Watkins, E.; Ehring, T. Prevention of anxiety disorders and depression by targeting excessive worry and rumination in adolescents and young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 90, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, E.R.; Mullan, E.; Wingrove, J.; Rimes, K.; Steiner, H.; Bathurst, N.; Eastman, R.; Scott, J. Rumination-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy for residual depression: Phase II randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E.R.; Roberts, H. Reflecting on rumination: Consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behav. Res. Ther. 2020, 127, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.S.; Sandman, C.F.; Craske, M.G. Positive and Negative Emotion Regulation in Adolescence: Links to Anxiety and Depression. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Huang, J.; An, Y.; Xu, W. The Relationship between stress and negative emotion: The Mediating role of rumination. Clin. Res. Trials 2018, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Bunce, H.L.I. The Potential for Outdoor Nature-Based Interventions in the Treatment and Prevention of Depression. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 740210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F.T.; Shansky, R.M. Adolescence: Vulnerable period for stress-induced prefrontal cortical function? Introduction to part IV. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1021, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston, C.; McEwen, B.S.; Casey, B.J. Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, L.M.; Pollak, S.D. Characterizing the Ruminative Process in Young Adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013, 42, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hossain, M.; Sultana, A.; Ma, P.; Fan, Q.; Sharma, R.; Purohit, N.; Sharmin, D.F. Effects of natural environment on mental health: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.A.; Brown, J.; Pervin, J.; Brabyn, S.; Pateman, R.; Breedvelt, J.; Gilbody, S.; Stancliffe, R.; McEachan, R.; White, P. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Astell-Burt, T.; Barber, E.A.; Brymer, E.; Cox, D.T.C.; Dean, J.; Depledge, M.; Fuller, R.A.; Hartig, T.; Irvine, K.N.; et al. Nature–Based Interventions for Improving Health and Wellbeing: The Purpose, the People and the Outcomes. Sports 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwan, K.; Giles, D.; Clarke, F.J.; Kotera, Y.; Evans, G.; Terebenina, O.; Minou, L.; Teeling, C.; Basran, J.; Wood, W.; et al. A pragmatic controlled trial of forest bathing compared with compassionate mind training in the UK: Impacts on self-reported wellbeing and heart rate variability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djernis, D.; Lundsgaard, C.M.; Rønn-Smidt, H.; Dahlgaard, J. Nature-Based Mindfulness: A Qualitative Study of the Experience of Support for Self-Regulation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, B.; Lecomte, T.; Fortin, G.; Masse, M.; Therien, P.; Bouchard, V.; Chapleau, M.-A.; Paquin, K.; Hofmann, S.G. Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Tucker, R.P.; Greene, P.A.; Davidson, R.J.; Wampold, B.E.; Kearney, D.J.; Simpson, T.L. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 59, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E.Y.; Jorgensen, A.; Sheffield, D. Does a natural environment enhance the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)? Examining the mental health and wellbeing, and nature connectedness benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 202, 103886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djernis, D.; Lerstrup, I.; Poulsen, D.; Stigsdotter, U.; Dahlgaard, J.; O’Toole, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nature-Based Mindfulness: Effects of Moving Mindfulness Training into an Outdoor Natural Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Grandpierre, Z. Mindfulness in Nature Enhances Connectedness and Mood. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.H.; Woo, J.-M.; Ryu, J.S. Effect of a forest therapy program and the forest environment on female workers’ stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S.; Nyed, P.K.; Sidenius, U.; Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K. A Long-Term Follow-Up of the Efficacy of Nature-Based Therapy for Adults Suffering from Stress-Related Illnesses on Levels of Healthcare Consumption and Sick-Leave Absence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Bunce, H.L.I. Nature-Based Meditation, Rumination and Mental Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, M.; Leivang, R.; Bunce, H. Nature-Based Guided Imagery and Meditation Significantly Enhance Mental Well-Being and Reduce Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized Experiment. Ecopsychology 2025, 17, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, S.; Tobin, D.; Avison, W.; Gilliland, J. Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwood, M.F.; Lakhani, A.; Fullagar, S.; Maujean, A.; Downes, M.; Byrne, J.; Stewart, A.; Barber, B.; Kendall, E. A narrative and systematic review of the behavioural, cognitive and emotional effects of passive nature exposure on young people: Evidence for prescribing change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegel, G.M.; Brown, K.W.; Shapiro, S.L.; Schubert, C.M. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for the Treatment of Adolescent Psychiatric Outpatients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.L. An Exploratory Study of Mindfulness Meditation for Alternative School Students: Perceived Benefits for Improving School Climate and Student Functioning. Mindfulness 2013, 5, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenner, C.; Herrnleben-Kurz, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 89024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoogman, S.; Goldberg, S.B.; Hoyt, W.T.; Miller, L. Mindfulness Interventions with Youth: A Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness 2014, 6, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymeus, F.; Lindberg, P.; Hartig, T. Building mindfulness bottom-up: Meditation in natural settings supports open monitoring and attention restoration. Conscious. Cogn. 2018, 59, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, J.; Cassano, M.; Perry-Parrish, C.; Stegall, S. Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2006, 27, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, C.; Walker, L.R.; Davis, M.; Irwin, C.E. Investing in the health and well-being of young adults. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlova, L.B.; Balon, R.; Beresin, E.V.; Brenner, A.M.; Coverdale, J.H.; Guerrero, A.P.; Louie, A.K.; Roberts, L.W. Psychoeducation as an Opportunity for Patients, Psychiatrists, and Psychiatric Educators: Why Do We Ignore It? Acad. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosen, E.; Woody, S.R. Brief psycho-education affects circadian variability in nicotine craving during cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 132, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Gauntlett-Gilbert, J. Mindfulness with children and adolescents: Effective clinical application. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hachette Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Porges, S.W. The polyvagal perspective. Biol. Psychol. 2007, 74, 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; Mathews, A. Mental imagery in emotion and emotional disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonduelle, S.L.; De Raedt, R.; Braet, C.; Campforts, E.; Baeken, C. Parental criticism affects adolescents’ mood and ruminative state: Self-perception appears to influence their mood response. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2023, 235, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, I.; Mor, N.; Chiorri, C.; Koster, E.H.W. The brief state rumination inventory (BSRI): Validation and psychometric evaluation. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2018, 42, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abend, R.; Dan, O.; Maoz, K.; Raz, S.; Bar-Haim, Y. Reliability, validity and sensitivity of a computerized visual analog scale measuring state anxiety. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2014, 45, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Pourtois, G. Transient state-dependent fluctuations in anxiety measured using STAI, POMS, PANAS or VAS: A comparative review. Anxiety Stress Coping 2012, 25, 603–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, E.G.; Ridler, I.; Ford, T.J.; Stringaris, A. Editorial Perspective: When is a ‘small effect’ actually large and impactful? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 64, 1643–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyo, M.; Wilson, K.A.; Ong, J.; Koopman, C. Mindfulness and rumination: Does mindfulness training lead to reductions in the ruminative thinking associated with depression? Explore 2009, 5, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, P.C. Mindfulness and coping with dysphoric mood: Contrasts with rumination and distraction. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2005, 29, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, R.E. Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Lykins, E.L.; Peters, J.R. Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of psychological wellbeing in long-term meditators and matched nonmeditators. J. Posit. Psychol. 2012, 7, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, K.D.; Monti, J.D.; Flynn, M. Stress Reactivity as a Pathway from Attentional Control Deficits in Everyday Life to Depressive Symptoms in Adolescent Girls. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroslavsky, I.; Allard, E.S.; Sanchez-Lopez, A. Can’t look Away: Attention control deficits predict Rumination, depression symptoms and depressive affect in daily Life. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, M.L.; Helminen, E.C.; Felver, J.C. A Systematic Review of Mindfulness Interventions on Psychophysiological Responses to Acute Stress. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2039–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Barbieri, G.; Donelli, D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lissnyder, E.; Koster, E.H.; Goubert, L.; Onraedt, T.; Vanderhasselt, M.-A.; De Raedt, R. Cognitive control moderates the association between stress and rumination. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2012, 43, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Alloy, L.B. A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E.; Brown, R.G. Rumination and executive function in depression: An experimental study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2002, 72, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.A.; Kenny, M.A.; Peña, A.S. Role of meditation to improve children’s health: Time to look at other strategies. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 57, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peskin, J.; Wells-Jopling, R. Fostering symbolic interpretation during adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 33, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiklejohn, J.; Phillips, C.; Freedman, M.L.; Griffin, M.L.; Biegel, G.; Roach, A.; Frank, J.; Burke, C.; Pinger, L.; Soloway, G.; et al. Integrating Mindfulness Training into K-12 Education: Fostering the Resilience of Teachers and Students. Mindfulness 2012, 3, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, A.R.; Torquati, J.C.; Beattie, H.L. Impact of Urban Nature on Executive Functioning in Early and Middle Childhood. Environ. Behav. 2015, 49, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Beauchamp, G. A study of the experiences of children aged 7–11 taking part in mindful approaches in local nature reserves. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2021, 21, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somsen, R.J. The development of attention regulation in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyken, W.; Ball, S.; Crane, C.; Ganguli, P.; Jones, B.; Montero-Marin, J.; Nuthall, E.; Raja, A.; Taylor, L.; Tudor, K.; et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: The MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. Évid. Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliburton, A.E.; Cooper, L.D. Applications and adaptations of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for adolescents. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2015, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetler, C.; Miller, G.E. Depression and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activation: A Quantitative Summary of Four Decades of Research. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Rosales, C.; Hernández, B.; Lorenzo, M. Benefits for emotional regulation of contact with nature: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1402885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, K.T.; Desai, A.; Field, J.; Miller, L.E.; Rausch, J.; Beebe, D.W. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.; Soenens, B.; Weinstein, N.; Vansteenkiste, M. Impact of Partial Sleep Deprivation on Psychological Functioning: Effects on Mindfulness and Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stores, G. Aspects of sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, D.G. Early Adversity and Development: Parsing Heterogeneity and Identifying Pathways of Risk and Resilience. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørndal, L.D.; Kendler, K.S.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Ystrom, E. Stressful life events increase the risk of major depressive episodes: A population-based twin study. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 5194–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Martiadis, V.; Martini, A.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Tabanico, J. Self, Identity, and the Natural Environment: Exploring Implicit Connections with Nature. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudworth, D.; Lumber, R. The importance of Forest School and the pathways to nature connection. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2021, 24, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Farb, N.A.; Goldin, P.R.; Fredrickson, B.L. Mindfulness Broadens Awareness and Builds Eudaimonic Meaning: A Process Model of Mindful Positive Emotion Regulation. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brent, D.A.; McMakin, D.L.; Kennard, B.D.; Goldstein, T.R.; Mayes, T.L.; Douaihy, A.B. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: A critical review of intervention studies. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balluerka, N.; Gorostiaga, A.; Alonso-Arbiol, I.; Aritzeta, A. Peer attachment and class emotional intelligence as predictors of adolescents’ psychological well-being: A multilevel approach. J. Adolesc. 2016, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Bergeman, C.S.; Bisconti, T.L.; Wallace, K.A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prev. Treat. 2000, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner-Seidler, A.; Banks, R.; Dunn, B.D.; Moulds, M.L. An investigation of the relationship between positive affect regulation and depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.J.; Nissen, J.B.; Mors, O.; Thomsen, P.H. Age and gender differences in depressive symptomatology and comorbidity: An incident sample of psychiatrically admitted children. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 84, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).