National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay: Results from the First Year of Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Background

2.2. Definition of Suicide Attempt

2.3. Data Items and Collection

- All ED presentations for suicide attempts;

- Diagnostic confirmation by a mental health professional;

- All methods of self-harm with suicidal intent.

- Self-harm without confirmed suicidal intent;

- Suicidal ideation without attempt;

- Accidental injuries;

- Fatal cases (suicides).

2.4. Quality Control

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations and Data Protection

3. Results

3.1. Suicide Attempts

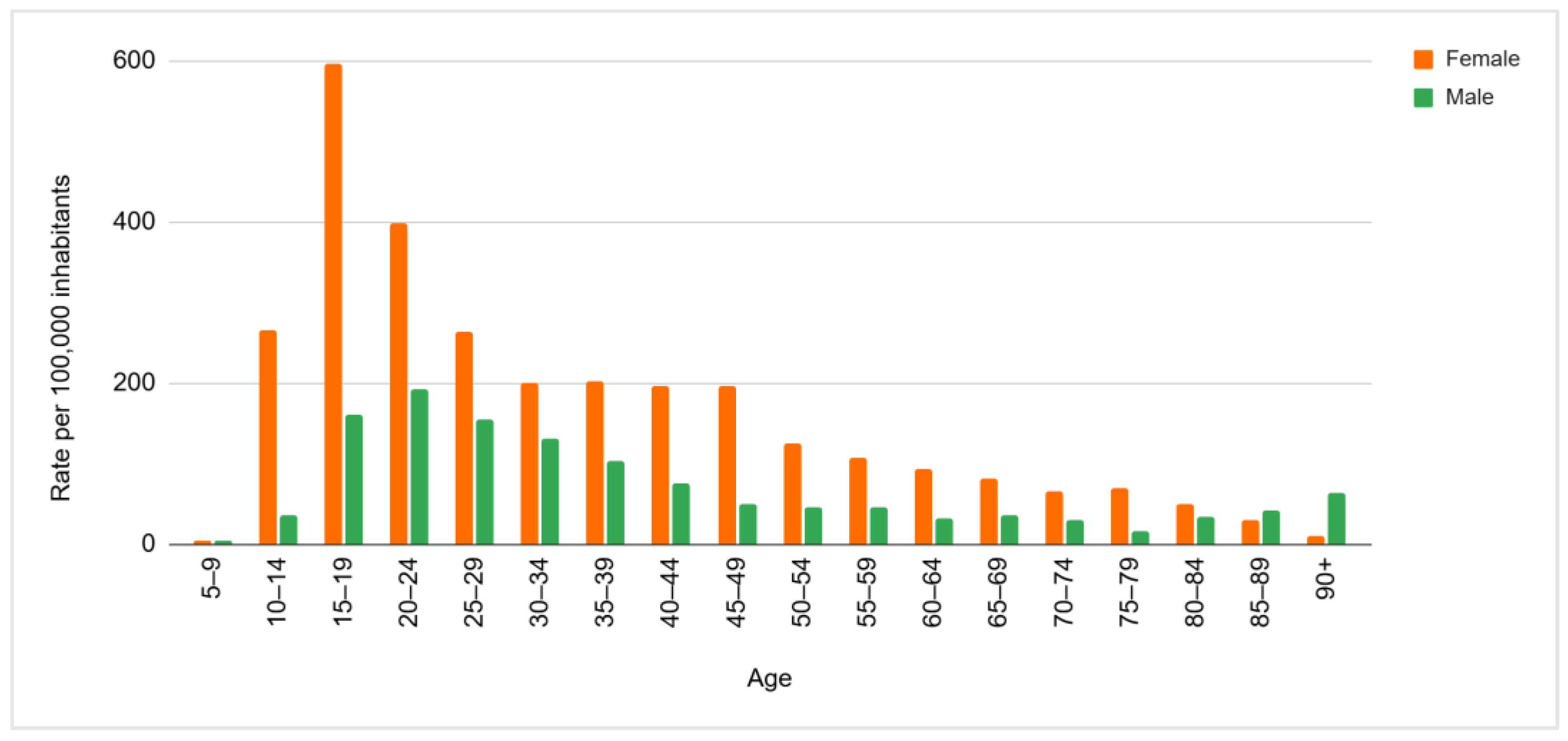

3.2. Gender and Age

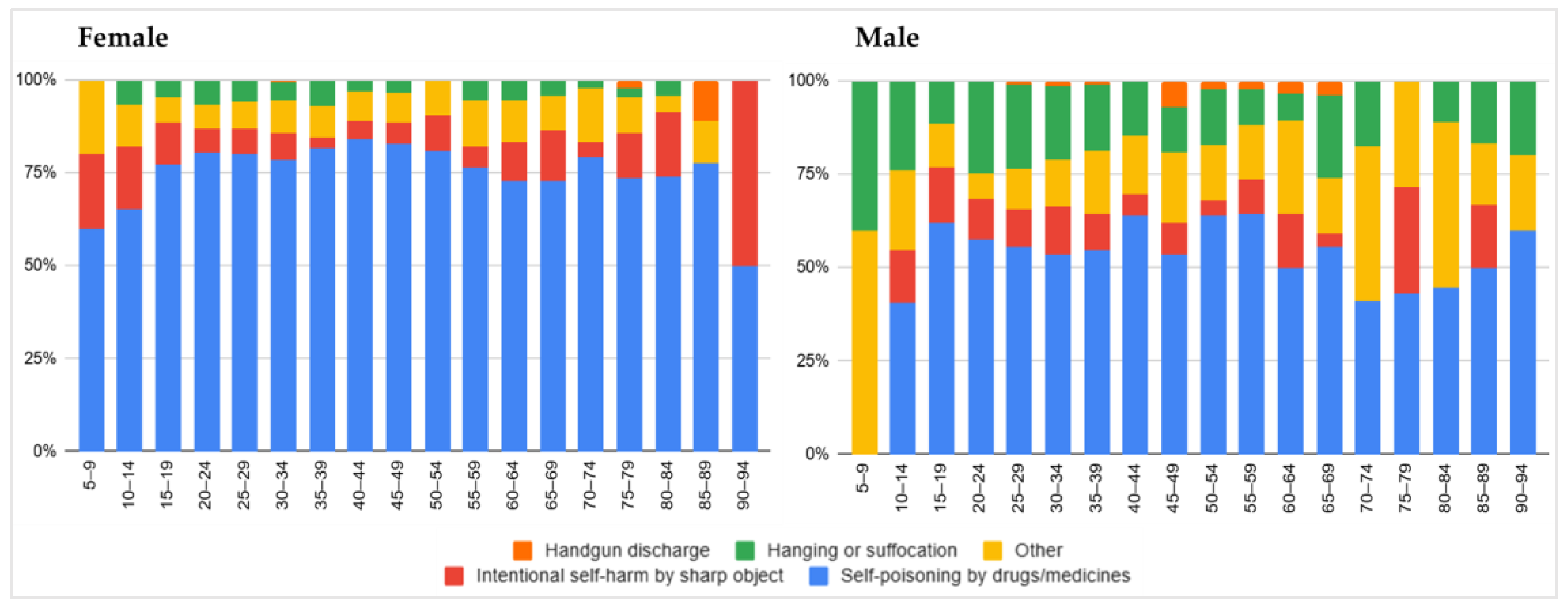

3.3. Method of Suicide Attempt

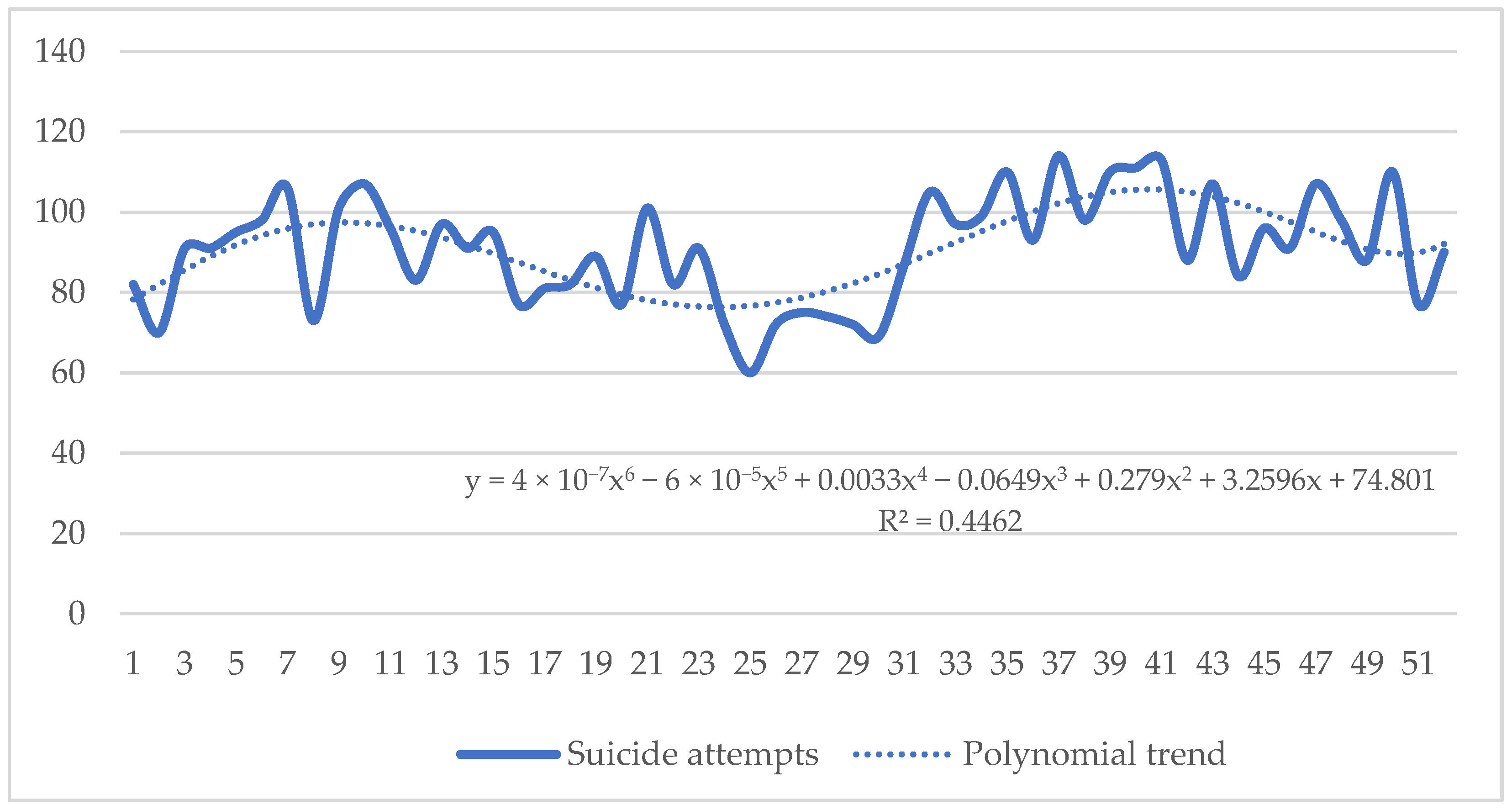

3.4. Variation by Day, Week, and Month

3.5. Repeated Suicide Attempts

3.6. Mental Health Care

3.7. Suicide Attempt Follow-Up

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019. Global Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Mortalidad por Suicidio en la Región de las Américas. Informe Regional 2015–2019; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Disparities in Suicide. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/disparities/index.html#:~:text=Suicide%20and%20suicide%20attempts%20are,mental%20healthcare%20access%2C%20among%20others (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Hafford-Letchfield, T.; Hanna, J.; Grant, E.; Ryder-Davies, L.; Cogan, N.; Goodman, J.; Rasmussen, S.; Martin, S. “It’s a Living Experience”: Bereavement by Suicide in Later Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Cayetano, C.; Jiang, H.; Tausch, A.; Oliveira, E.; Souza, R. Contextual factors associated with country-level suicide mortality in the Americas, 2000–2019: A cross-sectional ecological study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 20, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rando, K.; de Álava, L.; Dogmanas, D.; Rodríguez, M.; Irarrazaval, M.; Satdjian, J.L.; Moreira, A. Development and Implementation of National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Vignolo, J.; Alegretti, M.; Vacarezza, M.; Alvarez, C.; Retamoso, E. Estudio de 130 años de defunciones por Suicidio en el Uruguay 1887–2017. Rev. Salud Pública 2019, 23, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monza, A.; Cracco, C. Suicidio en Uruguay. Revisión de Políticas Públicas e Iniciativas Para Su Prevención; Organización Panamericana de la Salud-Coordinadora de Psicólogos del Uruguay: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Honoraria de Prevención del Suicidio. Estrategia Nacional de Prevención de Suicidio 2021–2025, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Publica: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2021.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Plan de Implementación de Prestaciones en Salud Mental, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2011.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Protocolo de Atención y Seguimiento a Las Personas Con Intento de Autoeliminación en el Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2017.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Guía de Práctica Clínica Abordaje de La Conducta Suicida Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2024.

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide—A Global Imperative, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Favril, L.; Yu, R.; Geddes, J.R.; Fazel, S. Individual-level risk factors for suicide mortality in the general population: An umbrella review. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostwick, J.; Pabbati, C.; Geske, J.; McKean, A. Suicide Attempt as a Risk Factor for Completed Suicide: Even More Lethal Than We Knew. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Practice Manual for Establishing and Maintaining Surveillance Systems for Suicide Attempts and Self-Harm, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Live Life: An Implementation Guide for Suicide Prevention in Countries, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, R.; Rigby, J.; Brunsdon, C.; Cully, G.; Too, L.; Arensman, E. Quantitative Methods to Detect Suicide and Self-Harm Clusters: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. Manual de Prácticas Para el Establecimiento y Mantenimiento de Sistemas de Vigilancia de Intentos de Suicidio y Autoagresiones, 1st ed.; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Training Manual for Surveillance of Suicide and Self-Harm in Communities via Key Informants, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Dogmanas, D.; de Álava, L.; Lapetina, A.; Porciúncula, H. Informe Sobre la Implementación del Formulario de Registro Obligatorio de Intentos de Autoeliminación (FRO-IAE); Área Programática para la Atención en Salud Mental-Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2021.

- Censo 2023. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/instituto-nacional-estadistica/comunicacion/noticias/resultados-finales (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Estimaciones y Proyecciones de la Población de Uruguay: Metodología y Resultados: Revisión 2013, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadistica: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2014.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Stat Bulk Data Download Service. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?name_desc=true (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Informe Cobertura Poblacional del SNIS Según Prestador, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018.

- Ley de Salud Mental (Centro de Información Oficial, 24/08/2017). Available online: https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/leyes/19529-2017 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Plan Nacional de Salud Mental 2020–2027, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Ley de Protección de Datos Personales (Centro de Información Oficial, 11/08/2008). Available online: https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/leyes/18331-2008 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Joyce, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Hursztyn, P.; O’Sullivan, G.; McGuiggan, J.C.; Nicholson, S.; Arensman, E.; Griffin, E.; Williamson, E.; Corcoran, P. National Self-Harm Registry Ireland Annual Report 2021, 1st ed.; National Suicide Research Foundation: Cork, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Suicide & Self-Harm Monitoring. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/intentional-self-harm-hospitalisations?__cf_chl_tk=WP8Q_TW8b.lxnBoIPxAj0u0oHLttLUNbGIY.htstEUY-1739378012-1.0.1.1-ab9qzfIOho.FNwbO2QeH0Q05PW2q8VGP3UN14UXDHfY (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Silva, A.; Vanzela, A.; Pedrollo, L.; Baker, J.; de Carvalho, J.; Sequeira, C.; Vedana, K.; Santos, J. Characteristics of surveillance systems for suicide and self-harm: A scoping review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.; Giglio, R.; Keyes, K.; DiMaggio, C.; Li, G. Risk markers for fatal and non-fatal prescription drug overdose: A meta-analysis. Inj. Epidemiol. 2017, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobravc, M.; Grabnar, I.; Brvar, M. Association between Prescribing and Intoxication Rates for Selected Psychotropic Drugs: A Longitudinal Observational Study. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Consumo de Benzodiacepinas y Otros Psicofármacos en Territorio Nacional, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2017.

- Lim, J.; Buckley, N.; Chitty, K.; Moles, R.; Cairns, R. Association Between Means Restriction of Poison and Method-Specific Suicide Rates: A Systematic Review. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e213042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, Y.; Sakata, N.; Takahashi, K.; Nishi, D.; Tachimori, H. Epidemiology of overdose episodes from the period prior to hospitalization for drug poisoning until discharge in Japan: An exploratory descriptive study using a nationwide claims database. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattimani, S.; Penchilaiya, V.; Sarkar, S.; Muthukrishnan, V. Temporal variations in suicide attempt rates: A hospital-based study from India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2016, 5, 357–361. [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra, D.; e Silva, A.; de Sousa-Rodrigues, C.; Barbosa, F.; de Siqueira, D.; Santos, J.; Barbosa, M.R.; de Medeiros Alves, V.; Nardi, A.E.; de Andrade, T.G. Do suicide attempts occur more frequently in the spring too? A systematic review and rhythmic analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, V.; Francisco, L.; de Melo, A.; Novaes, C.; Belo, F.; Nardi, A. Trends in suicide attempts at an emergency department. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2017, 39, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Klimiuk, K.; Krefta, D.; Krawczyk, M.; Balwicki, Ł. Seasonal Trends in Suicide Attempts-Keywords Related Searches: A Google Trends Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Kang, C.; Park, C.; Bell, M.; Armstrong, B.; Roye, D.; Hashizume, M.; Gasparrini, A.; Tobias, A.; Sera, F. Association of holidays and the day of the week with suicide risk: Multicountry, two stage, time series study. BMJ 2024, 387, e077262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freichel, R.; O’Shea, B.A. Suicidality and mood: The impact of trends, seasons, day of the week, and time of day on explicit and implicit cognitions among an online community sample. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, H.; Suominen, K.; Partonen, T.; Ostamo, A.; Lönnqvist, J. Time patterns of attempted suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 90, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, Y.; Youn, T.; Kim, B.; Park, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Hong, J. Association between level of suicide risk, characteristics of suicide attempts, and mental disorders among suicide attempters. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Wang, M.; Swaraj, S.; Olfson, M.; Large, M. Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Torre-Luque, A.; Pemau, A.; Ayad-Ahmed, W.; Borges, G.; Fernandez-Sevillano, J.; Garrido-Torres, N.; Garrido-Sanchez, L.; Garriga, M.; Gonzalez-Ortega, I.; Gonzalez-Pinto, A. Risk of suicide attempt repetition after an index attempt: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023, 81, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Witt, K.; Salisbury, T.; Arensman, E.; Gunnell, D.; Hazell, P.; Townsend, E.; van Heeringen, K. Psychosocial interventions following self-harm in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, M.; Kawashima, Y.; Yonemoto, N.; Yamada, M. Active contact and follow-up interventions to prevent repeat suicide attempts during high-risk periods among patients admitted to emergency departments for suicidal behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Dandona, R.; Silverman, M.; Khan, M.; Hawton, K. Preventing suicide: A public health approach to a global problem. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. CIE-10 Clasificación Estadística Internacional de Enfermedades y Problemas Relacionados Con la Salud, 10th ed.; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rando, K.; de Álava, L.; Dogmanas, D.; Rodríguez, M.; Alegretti, M.; Satdjian, J.L.; Moreira, A. National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay: Results from the First Year of Implementation. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010033

Rando K, de Álava L, Dogmanas D, Rodríguez M, Alegretti M, Satdjian JL, Moreira A. National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay: Results from the First Year of Implementation. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleRando, Karina, Laura de Álava, Denisse Dogmanas, Matías Rodríguez, Miguel Alegretti, Jose Luis Satdjian, and Alejandra Moreira. 2025. "National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay: Results from the First Year of Implementation" Psychiatry International 6, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010033

APA StyleRando, K., de Álava, L., Dogmanas, D., Rodríguez, M., Alegretti, M., Satdjian, J. L., & Moreira, A. (2025). National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay: Results from the First Year of Implementation. Psychiatry International, 6(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010033