Abstract

Introduction: Vitamin D plays a crucial role in brain health by providing antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective benefits. It regulates neurotransmitters and neurotrophins that are essential for the development, maintenance, and functioning of the nervous system. Deficiency in vitamin D during pregnancy and early childhood can disrupt neurodevelopment, potentially contributing to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The aim of this narrative review was to analyze the potential link between vitamin D deficiency and the development of ASD, as well as to explore the therapeutic benefits of vitamin D supplementation. Method: We performed a literature search across PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library databases, reviewing observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and meta-analyses for evidence of an association between vitamin D deficiency and ASD. Results: The results were mixed but promising, with most observational studies suggesting a positive link between vitamin D deficiency and ASD, though these findings were not consistently replicated in prospective studies or RCTs. In conclusion, the available data are insufficient to establish vitamin D deficiency as a definitive cause of ASD. Further RCTs, particularly during pregnancy and infancy, are needed to better understand the role of vitamin D in the etiology of ASD and its potential as a therapeutic intervention. Conclusions: The current available data are insufficient to support vitamin D deficiency as a definitive factor in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders. To translate this hypothesis into clinical practice, additional randomized controlled trials, particularly during pregnancy and early infancy, are needed.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is categorized as a neurodevelopmental disorder presenting with a lack of social interaction and communication and repetitive and stereotypical behaviors [1]. ASD is a polygenic multifactorial illness resulting from the interplay between genes and the environment [2]. The literature suggests that genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of ASD [3,4]. However, only 25–30% of children with ASD have shown genetic abnormality, while 70% did not show any such abnormality, suggesting the role of environmental factors [4]. Environmental factors, including maternal folic acid and vitamin D (VD) deficiency, medication use during pregnancy, maternal smoking, infections during pregnancy, exposure to toxic substances, and vaccines, are associated with ASD [5].

Based on data from Cannell’s epidemiological survey, there was a higher prevalence of ASD in urban areas, at higher elevations, and in locations with more air pollution [6]. Air pollution, cloudy weather, seasonal variations, dark-skinned immigrants, migration to poleward latitudes, and nutrition are specific factors linked to both ASD and VD deficiency [7]. Through its effects on immune modulation, neurotrophic factors, neurotransmitters, and gene regulation, processes that are similarly dysregulated in ASD, vitamin D plays a crucial role in neurodevelopment [8]. In contrast to other non-genetic causes, VD insufficiency is a distinct and biologically plausible contributing factor.

A wealth of emerging studies links maternal and childhood VD deficiency to increased risk and severity of ASD, emphasizing its potential as an actionable and feasible focus for intervention. Considering the worldwide prevalence of VD deficiency, addressing this factor could potentially reduce ASD incidence and severity. This review examines existing evidence on VD deficiency as a modifiable risk factor for ASD, highlighting its role in pathophysiology and implications for prevention and treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

To explore and evaluate the broad range of topics related to the hypothesis that vitamin D deficiency may contribute to ASD, we opted to conduct a narrative review. Search strategies: We performed a literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library databases. The search terms included a combination of MeSH terms and free-text keywords. The search strategy used the following Boolean operators: (“Autism” OR “Autism Spectrum Disorder” OR “ASD” OR “Autistic”)AND (“Vitamin D” OR “1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3” OR “25-hydroxyvitamin D2” OR “25-hydroxyvitamin D3” OR “25(OH)D”) AND (“Supplements” OR “Supplementation” OR “Intake”).

Inclusion criteria included observational studies, including case–control, cohort, and register-based surveys, that assessed the association between gestational vitamin D (VD) deficiency and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis in offspring. Additionally, we considered observational studies evaluating VD levels in neonates and children diagnosed with ASD. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effects of VD supplementation in neonates and children under 18 years with ASD were also included. Furthermore, we incorporated meta-analyses that examined the association between VD deficiency and ASD, as well as meta-analyses evaluating the efficacy of VD supplementation in ASD.

The Newcastle–Ottawa quality scale for case–control and cohort study assessment was used to evaluate the quality of case–control studies included in this study [9]. We included two case–control studies, two nested controls, two prospective cohort studies, and one register-based population survey assessing the association between maternal VD deficiency and the diagnosis of ASD in offspring. Five case–control studies evaluating the association of VD levels in neonates and ASD diagnosis and eleven case–control studies examining the VD deficiency in children and the diagnosis of ASD were included. All relevant RCTs of VD supplementation alone in children with ASD <18 years of age were included in our study. After the search and exclusion of duplication, 7 RCTs were included in our study. Two meta-analyses of case–control studies and three meta-analyses of RCTs of VD supplementation were also included.

We excluded studies published in languages other than English. Narrative reviews, expert opinions, commentaries, letters, and conference abstracts without original data were also excluded. Studies with incomplete or insufficient data, such as missing key outcome measures or lacking statistical analysis, were not considered. Research that did not use established diagnostic criteria for ASD (e.g., DSM or ICD classifications) or assessed VD levels without a control group was excluded. Duplicate studies or those using overlapping data without new insights were removed. Case reports and small case series with limited sample sizes, as well as studies with a high risk of bias, poor study design, or inadequate control for confounders, were also excluded.

3. Results

3.1. Linking Vitamin D with Autism

VD, in addition to regulating calcium and phosphorus metabolism, has an important role in neurodevelopment. Growing research indicates that vitamin D deficiency likely plays a role in the pathophysiology of ASD [8]. Concurrently, research has demonstrated the role of VD supplementation in treating the primary symptoms of ASD in children [10].

VD exists in two distinct forms: VD2 and D3. Vitamin D3 is mostly created in the skin by ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC), whereas vitamin D2 is derived from food. VD is essential for the proper functioning of the neurological system. It functions via vitamin D receptors (VDR) found in the neurons and glial cells. VDR is expressed most highly in the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, substantia nigra, orbitofrontal cortex, cingulate, and amygdala. The presence of both VDR and the enzyme that converts 25 hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] to the active form 1,25 di-hydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25 5(OH2)D3] in the brain is important evidence supporting the involvement of VD in brain functioning. The active form, 1,25(OH2)D3, is suggested to be a neurosteroid hormone that stimulates cell division and proliferation. VD demonstrates anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. It plays a significant role in the expression of genes and proteins essential to neuron physiology, neurotrophin expression, intracellular calcium signaling, neurotransmitter release, and neuronal differentiation [11].

Studies indicate that VD plays a role in synaptic transmission, particularly chemical synapses [12]. Because VD deficiency increases the amounts of cholesterol in the presynaptic membrane and vesicles, it alters the fusion characteristics of the synaptic membrane and affects the efficiency of neurotransmitter release [13]. Conversely, VD treatment may partially restore vesicle fusion capacity [14]. Furthermore, VD affects the transcription of proteins such as complexin2 and synaptojanin1 which are important for neurotransmitter release [15,16]. VD directly boosts the activity of voltage-dependent calcium channels [17] and promotes the expression of calcium sensors such as syt1 and syt2 in the brain [18], thereby influencing synchronized transmitter release. As a result, VD deficiency can affect all those functions that rely on efficient neurotransmitter release and good neuronal connectivity such as cognition, learning, and behavior [19]. Research has shown abnormalities of neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin, and acetylcholine in children with ASD [20]. Consequently, it seems reasonable to presume that VD deficiency is a contributing factor in the etiopathogenesis of ASD.

Vitamin D (VD) plays a crucial role in regulating neurotransmitter release and metabolism by modulating the expression of receptors, transporters, and enzymes. VD deficiency has been associated with a decline in the expression of the excitatory amino acid transporter (EAAT) and GABA transporter 3 (GAT3), resulting in impaired glutamate and GABA reuptake systems [21]. Additionally, VD deficiency reduces the expression of glutamate synthetase 1, glutamate decarboxylase, and GABA receptor mRNA [22,23,24].

GABA serves as the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the developing brain, and disruptions in its function can affect critical neurodevelopmental processes such as cell differentiation, synapse maturation, neuronal migration, and proliferation [25]. Similarly, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is hypothesized to arise from imbalances in the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems, leading to an altered excitatory/inhibitory equilibrium. This dysregulation, particularly in the medial prefrontal cortex, contributes to impaired information processing and dysfunctional social behavior [25].

Furthermore, magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies have revealed lower glutamate concentrations in the striatum of adults with ASD and ASD mouse models compared to controls [26]. Given its role in neurotransmitter synthesis, VD may help regulate excitatory and inhibitory signaling, thereby influencing neurodevelopmental and cognitive functions [27].

VD may promote the synthesis of neurotrophins such as the nerve growth factor (NGF) and the glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [28], which are important for the growth and function of neurons [29]. However, one meta-analysis [30] indicated that children with ASD had considerably greater levels of NGF than controls, indicating that the role of neurotrophins in ASD is not well understood. Nevertheless, studies have indicated that VD increases the expression of neurotrophins [31], which has positive effects on the developing brain; yet, there is little experimental data regarding children with ASD.

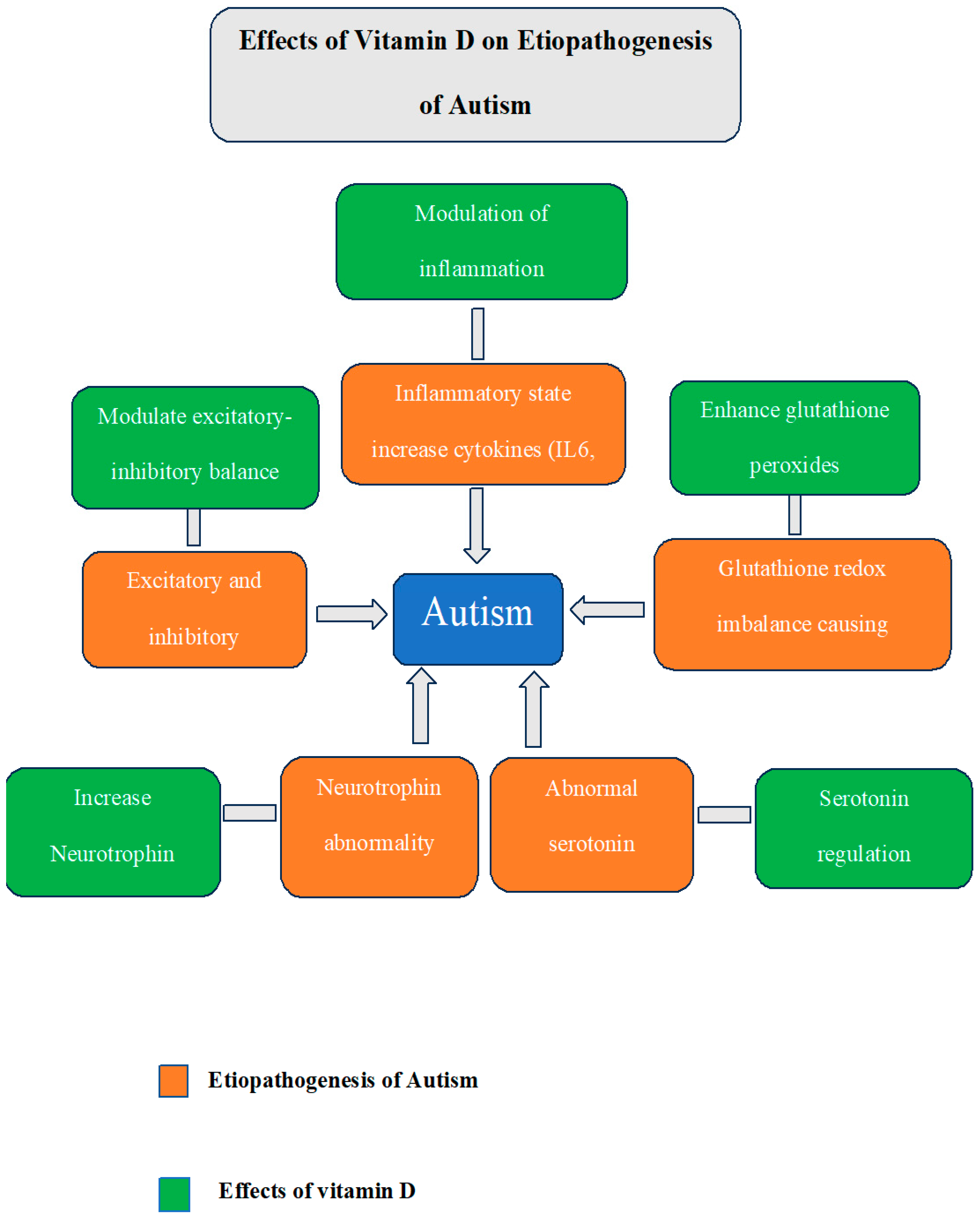

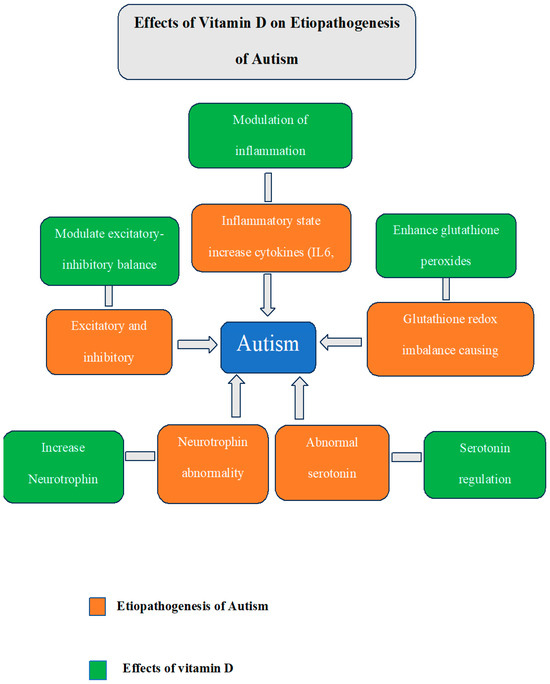

Children with ASD have higher levels of inflammation. ASD children are reported to have elevated proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin IL-6, IL-8, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [32]. Research employing mice as model organisms for autism has demonstrated that elevated levels of IL-6 affect synaptic transmissions and result in traits similar to autism, such as decreased social engagement and difficulties with learning [33]. A systematic review of normally developing children and adolescents concluded that VD status negatively correlated with inflammation [34]. Similarly, another systematic review of immune cell studies found that VD supplementation consistently reduced IL-6 and IL-8 [35]. Additionally, VD helps to increase the levels of glutathione peroxidase 1 (GP1), which lowers oxidative stress [36] and helps regulate glutathione redox imbalance, which is another contributing factor to ASD [37]. A summary of actions of VD on brain addressing various etiological factors implicated in ASD is depicted in Figure 1

Figure 1.

Summary of the various etiological factors implicated in ASD and the desirable effects of VD that can counter these factors.

3.2. Evidence of the Relationship Between Vitamin D Deficiency and ASD

Animal studies have reported behavioral abnormalities in the offspring of VD-deficient mice. The offspring of deficient mice showed a lack of dam/pup interactions, like maternal licking and grooming [38]. As juveniles or adults, these offspring showed social and behavioral deficits and stereotyped behaviors similar to ASD symptoms [39,40]. Hyperactivity, impulsivity, and sensory sensitivity were also reported in the offspring of vitamin D-deficient rats [41].

A strong correlation was found between maternal VD deficiency and an increased risk of ASD in offspring. Observational studies reported a varied risk of autism depending on the season of birth and latitude [42]. Conception during fall in the northern hemisphere region was linked to a 6% higher risk of autism compared with summer births [Odds Ratio = 1.06, 95% CI (1.02–1.10)] [42,43,44]. Being the child of a dark-skinned immigrant in a cold country increased the likelihood of developing ASD [45,46,47]. These results made VD deficiency a strong contender to account for these findings. The observational studies of the mother’s serum VD levels during pregnancy and the assessment of the offspring’s risk of an ASD diagnosis are shown in Table 1 [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Most studies showed a negative correlation between maternal serum 25 hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH) D) levels and a diagnosis of ASD [48,49,50,51,53], except for a few [52,54]. Nonetheless, a prospective study using Mendelian randomization did not find compelling evidence linking a mother’s vitamin D levels during pregnancy to an offspring’s diagnosis of ASD [54]; see Table 2.

Table 1.

Overview of cross-sectional studies showing an association between maternal vitamin D deficiency and ASD.

Table 2.

Overview of longitudinal studies showing an association between maternal vitamin D deficiency and ASD.

Studies conducted with neonates [50,55,56,57,58] ato assess the association between VD deficiency and ASD are shown in Table 3 Three case–control studies [50,51,55] of neonates showed increased risk, while another three [56,57,58] did not show a significant increase in risk of ASD, and two longitudinal studies failed to show any such association; see Table 4. Most case–control studies [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] of children have shown a significant association between VD deficiency and ASD, except for two (see Table 5). Moreover, two meta-analyses demonstrated that children with ASD had considerably lower serum concentrations of 25(OH) D than typically developing (TD) children [70,71]; see Table 6. However, the conclusions of these studies shall be interpreted cautiously. The generalizability of these findings is limited because most studies had small sample sizes and were geographically limited. Some studies used secondary care records to derive vitamin D status and did not address the confounders like immigration, disadvantaged social status, lifestyle factors, psychiatric illness in mothers, and psychotropic drug use. Many studies did not measure other nutrients that have a role in neurodevelopment and could have been the actual cause of the increased risk of ASD. Few vitamin D studies have used the same cut-off values for deficiency in both mothers and neonates. The scales used to measure ASD such as the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) can show higher scores in children with other childhood communication disorders. Moreover, VD deficiency is inseparable from other modifiable risk factors, making it difficult to assume a causal relationship.

Table 3.

Overview of cross-sectional studies showing an association between neonatal vitamin D deficiency and ASD.

Table 4.

Overview of longitudinal studies showing an association between neonatal vitamin D deficiency and ASD.

Table 5.

Overview of studies showing an association between vitamin D deficiency and ASD in children.

Table 6.

Overview of metanalysis showing an association between Vitamin D deficiency and ASD.

3.3. Evidence of Improvement with Vitamin D Supplementation

Multivitamin intake in pregnancy has shown a reduced risk of ASD [72]. However, evidence to support the role of VD supplementation for ASD treatment is less clear. Feng et al. [73] included 285 healthy controls and 215 children with ASD (mean age 5.1 years old) in an open-label study. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) were used to evaluate the symptoms of ASD. When the ASD children received VD supplementation for three months at a dose of 150,000 IU/month i.d. + 400 IU/day, their scores on the ABC and CARS considerably improved. However, most randomized control trials (RCTs) have shown no significant improvement in ASD with VD supplementation; see Table 7. Most RCTs showed potential bias due to uncertain allocation concealment and inadequate blinding [74,75,76,77,78,79]. Most studies showed no improvement in the core symptoms of ASD between groups, while there was a decrease in symptoms within groups, before and after the administration of the VD supplement [74,75,76,77,78,79]. Two RCTs have demonstrated a reduction in hyperactivity [76,78], while no change in irritability and sensory symptoms [79] was noted in the ASD group compared to placebo. Additionally, supplementing with VD has been demonstrated to lessen stereotypes [79,80]. Serotonin and dopamine abnormalities have been documented in children diagnosed with autism [81]. Studies have also reported that children with autism exhibit stereotypic behavior due to serotonin and dopamine abnormalities [82]. Since VD regulates serotonin synthesis, its supplementation can improve stereotypes [83]. According to meta-analysis (Table 8), the core symptoms of ASD did not improve [84,85,86], while hyperactivity [85] and stereotypes [86] decreased significantly in children receiving VD supplementation. Most RCTs were conducted on small sample sizes and were limited to a specific geographical area, limiting the generalizability. Based on these results, it is too premature to conclude that VD supplementation can treat ASD. More research is required to determine which children can benefit from VD supplements and what dosage has the best chance of working while posing the least risk of negative side effects.

Table 7.

Overview of RCTs of vitamin D supplementation for treating ASD.

Table 8.

Overview of meta-analysis showing the effect of vitamin D supplementation on symptoms of ASD.

Studies regarding the prophylactic administration of VD in pregnant women to prevent ASD are very few. Stubbs et al. [87] reported a reduced risk of ASD in the children of mothers supplemented with VD. A dose of 5000 IU/day was given to pregnant women with a previous child with an ASD diagnosis, and newborns were given 1000 IU/day from birth until three years. The children of supplemented mothers had a fourfold less chance of developing ASD as compared to non-supplemented mothers [87]. In a more recent study, high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation from pregnancy week 24 until 1 week postpartum did not reduce the overall risk of autism [88]. However, the findings of these studies shall be interpreted with care due to the small sample size and varied duration of VD administration among women [87,88]. Some women were taking VD before pregnancy while others were prescribed VD at different trimesters [87].

In conclusion, the data available for VD prophylaxis in mothers to prevent ASD in children are currently insufficient.

4. Discussion

The existing evidence about VD deficiency in the etiopathogenesis of ASD and its supplementation in treatment is inadequate. A recent study by Gao et al. [89] reported no causal link between VD deficiency and ASD, while reverse analysis showed ASD leading to VD deficiency. In actuality, reverse causality could account for the substantial body of observational studies demonstrating a positive correlation between VD deficiency and ASD. Our discussion will focus on VD functions—like neuroprotection, inflammation, and gene expression—and their rationale for effectiveness in treating ASD.

The neuroprotective effect of VD may not be sufficient to treat ASD patients, as the neurotransmitters, synaptic connections, and the shaping of neural circuitry do not holistically depend on the role of VD [90] in neurodevelopment. The mere fact that VD can easily pass through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) does not mean it can affect brain cells. Its role in neurodevelopment depends on other factors such as the residual amount of VD in the brain, its metabolism, and its utilization by brain cells [91].

ASD patients have been shown to have increased neuroinflammation characterized by an increase in proinflammatory cytokines [92]. Vitamin D may suppress proinflammatory cytokines and enhance anti-inflammatory cytokines [93]. However, VD cannot fully address the extensive neuroinflammatory abnormalities observed in ASD.

A wide range of genetic abnormalities with complex mechanisms of gene regulation and expression were noted with ASD [94]. While VD plays an important role in gene expression, it cannot solely change the complex gene regulatory system in ASD. In addition, epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation and histone modification are noted in ASD, and VD has a limited role in epigenetic regulation [95].

More research is warranted to conclude the role of VD, its safe dose, and the timing of treatment initiation in ASD patients. The initiation of VD at an appropriate time when neurodevelopment is taking place in the fetus is the key to preventing brain lesions in ASD. More RCTs are required to determine the efficacy of VD supplementation in children with ASD while controlling for all potential confounders.

5. Conclusions

Our summary shows mixed results about the effectiveness of VD supplementation in ASD. For clinicians, this suggests a potential complementary intervention for ASD management, especially in cases of vitamin D deficiency. Therefore, it should be considered alongside other treatments for ASD, such as behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy. Dosage, duration, and patient-specific factors must be carefully managed to avoid toxicity.

Author Contributions

S.S., Conceptualization and design of work, methodology, resources; S.S., N.A., R.S., M.A.A., G.A., L.A.-A., N.E.M. and M.S., software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation; S.S., writing—original draft preparation; S.S., N.E.M., R.S., M.A.A., G.A., L.A.-A. and M.S., writing—review and editing; S.S., final approval of the version to be published; S.S., accountability for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of Dr. Soliman Fakeeh Hospital determined that ethical approval was not required for this study, as it is a narrative review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Xue, K.; Gu, S.; Lv, L.; Huang, S.; Xie, W. Potential role of genomic imprinted genes and brain developmental related genes in autism. BMC Med. Genom. 2020, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C.; Brugha, T.S.; Charman, T.; Cusack, J.; Dumas, G.; Frazier, T.; Jones, E.J.H.; Jones, R.M.; Pickles, A.; State, M.W.; et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Gooch, H.; Petty, A.; McGrath, J.J.; Eyles, D. Vitamin D and the brain: Genomic and non-genomic actions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bölte, S.; Girdler, S.; Marschik, P.B. The contribution of environmental exposure to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1275–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modabbernia, A.; Velthorst, E.; Reichenberg, A. Environmental risk factors for autism: An evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Mol. Autism 2017, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, J.J. Autism and vitamin D. Med. Hypotheses 2008, 70, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zou, Z.; Yang, L.; He, X.; Wu, J.; Ma, J.; et al. Research Progress on the Role of Vitamin D in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 859151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzghoul, L. Role of Vitamin D in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 4357–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittana, M.; Ahmadani, A.; Stojanovska, L.; Attlee, A. The Role of Vitamin D Supplementation in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, S. Neuroimaging changes associated with vitamin D Deficiency—A narrative review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, P.E.; Burne, T.H. Vitamin D in Synaptic Plasticity, Cognitive Function, and Neuropsychiatric Illness. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasatkina, L.A.; Gumenyuk, V.P.; Sturm, E.M.; Heinemann, A.; Bernas, T.; Trikash, I.O. Modulation of neurosecretion and approaches for its multistep analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasatkina, L.A.; Tarasenko, A.S.; Krupko, O.O.; Kuchmerovska, T.M.; Lisakovska, O.O.; Trikash, I.O. Vitamin D deficiency induces the excitation/inhibition brain imbalance and the proinflammatory shift. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 119, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, C.S.; Brewer, L.D.; Searcy, J.L.; Chen, K.-C.; Popović, J.; Kraner, S.D.; Thibault, O.; Blalock, E.M.; Landfield, P.W.; Porter, N.M. Vitamin D prevents cognitive decline and enhances hippocampal synaptic function in aging rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4359-66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landel, V.; Millet, P.; Baranger, K.; Loriod, B.; Féron, F. Vitamin D interacts with Esr1 and Igf1 to regulate molecular pathways relevant to Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooch, H.; Cui, X.; Anggono, V.; Trzaskowski, M.; Tan, M.C.; Eyles, D.W.; Burne, T.H.J.; Jang, S.E.; Mattheisen, M.; Hougaard, D.M.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D modulates L-type voltage-gated calcium channels in a subset of neurons in the developing mouse prefrontal cortex. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Südhof, T.C. Calcium Control of Neurotransmitter Release. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 4, a011353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.B.J.; Barros, W.M.A.; da Silva, M.L.; Silva, J.M.L.; Souza, A.P.D.S.; Silva, K.G.D.; Lagranha, C.J. Impact of vitamin D on cognitive functions in healthy individuals: A systematic review in randomized controlled clinical trials. Front. Psychol. 2023, 28, 1150187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, R.; Risoleo, M.C.; Messina, G.; Parisi, L.; Carotenuto, M.; Vetri, L.; Roccella, M. The Neurochemistry of Autism. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krisanova, N.; Pozdnyakova, N.; Pastukhov, A.; Dudarenko, M.; Maksymchuk, O.; Parkhomets, P.; Sivko, R.; Borisova, T. Vitamin D3 deficiency in puberty rats causes presynaptic malfunctioning through alterations in exocytotic release and uptake of glutamate/GABA and expression of EAAC-1/GAT-3 transporters. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 123, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féron, F.; Burne, T.; Brown, J.; Smith, E.; McGrath, J.; Mackay-Sim, A.; Eyles, D. Developmental Vitamin D3 deficiency alters the adult rat brain. Brain Res. Bull. 2005, 65, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, N.J.; Kesby, J.P.; Eyles, D.W.; McGrath, J.J.; Mackay-Sim, A.; Burne, T.H. Adult vitamin D deficiency leads to behavioural and brain neurochemical alterations in C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 241, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Zhang, L.-H.; Cai, H.-L.; Li, H.-D.; Liu, Y.-P.; Tang, M.-M.; Dang, R.-L.; Zhu, W.-Y.; Xue, Y.; He, X. Neurochemical Effects of Chronic Administration of Calcitriol in Rats. Nutrients 2014, 6, 6048–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, D.F.; Kriegstein, A.R. Is there more to gaba than synaptic inhibition? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yizhar, O.; Fenno, L.E.; Prigge, M.; Schneider, F.; Davidson, T.J.; O’shea, D.J.; Sohal, V.S.; Goshen, I.; Finkelstein, J.; Paz, J.T.; et al. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 2011, 477, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horder, J.; Petrinovic, M.M.; Mendez, M.A.; Bruns, A.; Takumi, T.; Spooren, W.; Barker, G.J.; Künnecke, B.; Murphy, D.G. Glutamate and GABA in autism spectrum disorder—A translational magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in man and rodent models. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, D.; Brown, J.; Mackay-Sim, A.; McGrath, J.; Feron, F. Vitamin d3 and brain development. Neuroscience 2003, 118, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, E.J.; Reichardt, L.F. Neurotrophins: Roles in Neuronal Development and Function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 677–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-H.; Shi, X.-J.; Fan, F.-C.; Cheng, Y. Peripheral blood neurotrophic factor levels in children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orme, R.P.; Bhangal, M.S.; Fricker, R.A. Calcitriol Imparts Neuroprotection In Vitro to Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons by Upregulating GDNF Expression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Quintana, D.S.; Glozier, N.; Lloyd, A.R.; Hickie, I.B.; Guastella, A.J. Cytokine aberrations in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Li, X.; Zhong, Y. Inflammatory Cytokines: Potential Biomarkers of Immunologic Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 531518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filgueiras, M.S.; Rocha, N.P.; Novaes, J.F.; Bressan, J. Vitamin D status, oxidative stress, and inflammation in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calton, E.K.; Keane, K.N.; Newsholme, P.; Soares, M.J. The Impact of Vitamin D Levels on Inflammatory Status: A Systematic Review of Immune Cell Studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, M.G.A.; Sabico, S.; Clerici, M.; Khattak, M.N.K.; Wani, K.; Al-Musharaf, S.; Amer, O.E.; Alokail, M.S.; Al-Daghri, N.M. Vitamin D Supplementation is Associated with Increased Glutathione Peroxidase-1 Levels in Arab Adults with Prediabetes. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørklund, G.; Tinkov, A.A.; Hosnedlová, B.; Kizek, R.; Ajsuvakova, O.P.; Chirumbolo, S.; Skalnaya, M.G.; Peana, M.; Dadar, M.; El-Ansary, A.; et al. The role of glutathione redox imbalance in autism spectrum disorder: A review. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, N.J.; Tesic, D.; Feindel, K.W.; Smith, J.T.; Clarke, M.W.; Wale, C.; Crew, R.C.; Wharfe, M.; Whitehouse, A.J.; Wyrwoll, C.S. Vitamin D is crucial for maternal care and offspring social behavior in rats. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 237, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Vasileva, S.; Langguth, M.; Alexander, S.; Cui, X.; Whitehouse, A.; McGrath, J.J.; Eyles, D. Developmental Vitamin D Deficiency Produces Behavioral Phenotypes of Relevance to Autism in an Animal Model. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamang, M.K.; Ali, A.; Pertile, R.N.; Cui, X.; Alexander, S.; Nitert, M.D.; Palmieri, C.; Eyles, D. Developmental vitamin D-deficiency produces autism-relevant behaviours and gut-health associated alterations in a rat model. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overeem, K.A.; Eyles, D.W.; McGrath, J.J.; Burne, T.H. The impact of vitamin D deficiency on behavior and brain function in rodents. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 7, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Soles, C.M. Epidemiologic evidence for supporting the role of maternal vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for the development of infantile autism. Derm. -Endocrinol. 2009, 1, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerbo, O.; Iosif, A.-M.; Delwiche, L.; Walker, C.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Month of Conception and Risk of Autism. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humble, M.B.; Gustafsson, S.; Bejerot, S. Low serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD) among psychiatric out-patients in Sweden: Relations with season, age, ethnic origin, and psychiatric diagnosis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, D.W. Vitamin D and autism: Does skin colour modify risk? Acta Paediatr. 2010, 99, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, C.; Rai, D.; Goodman, A.; Lundberg, M.; Idring, S.; Svensson, A.; Koupil, I.; Serlachius, E.; Dalman, C. Migration and autism spectrum disorder: Population-based study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Ven, E.; Termorshuizen, F.; Laan, W.; Breetvelt, E.J.; Van Os, J.; Selten, J.P. An incidence study of diagnosed autism-spectrum disorders among immigrants to the Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012, 128, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xin, K.; Wei, J.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, H. Lower maternal serum 25(OH) D in first trimester associated with higher autism risk in Chinese offspring. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 89, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, C.; Kosidou, K.; Dalman, C.; Lundberg, M.; Lee, B.K.; Rai, D.; Karlsson, H.; Gardner, R.; Arver, S. Maternal vitamin D deficiency and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: Population-based study. BJPsych Open 2016, 2, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinkhuyzen, A.A.E.; Eyles, D.W.; Burne, T.H.J.; Blanken, L.M.E.; Kruithof, C.J.; Verhulst, F.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Tiemeier, H.; McGrath, J.J. Gestational vitamin D deficiency and autism-related traits: The Generation R Study. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.K.; Eyles, D.W.; Magnusson, C.; Newschaffer, C.J.; McGrath, J.J.; Kvaskoff, D.; Ko, P.; Dalman, C.; Karlsson, H.; Gardner, R.M. Developmental vitamin D and autism spectrum disorders: Findings from the Stockholm Youth Cohort. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 26, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windham, G.C.; Pearl, M.; Poon, V.; Berger, K.; Soriano, J.W.; Eyles, D.; Lyall, K.; Kharrazi, M.; Croen, L.A. Maternal Vitamin D Levels During Pregnancy in Association With Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) or Intellectual Disability (ID) in Offspring; Exploring Non-linear Patterns and Demographic Sub-groups. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 2216–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourander, A.; Upadhyaya, S.; Surcel, H.-M.; Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S.; Cheslack-Postava, K.; Silwal, S.; Sucksdorff, M.; McKeague, I.W.; Brown, A.S. Maternal Vitamin D Levels During Pregnancy and Offspring Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 90, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madley-Dowd, P.; Dardani, C.; Wootton, R.E.; Dack, K.; Palmer, T.; Thurston, R.; Havdahl, A.; Golding, J.; Lawlor, D.; Rai, D. Maternal vitamin D during pregnancy and offspring autism and autism-associated traits: A prospective cohort study. Mol. Autism 2022, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernell, E.; Bejerot, S.; Westerlund, J.; Miniscalco, C.; Simila, H.; Eyles, D.; Gillberg, C.; Humble, M.B. Autism spectrum disorder and low vitamin D at birth: A sibling control study. Mol. Autism 2015, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Anderson, L.N.; Smile, S.; Chen, Y.; Borkhoff, C.M.; Koroshegyi, C.; Lebovic, G.; Parkin, P.C.; Birken, C.S.; Szatmari, P.; et al. Prospective cohort study of vitamin D and autism spectrum disorder diagnoses in early childhood. Autism 2018, 23, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Niu, Q.; Eyles, D.W.; Hansen, R.L.; Iosif, A. Neonatal vitamin D status in relation to autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay in the CHARGE case–control study. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windham, G.C.; Pearl, M.; Anderson, M.C.; Poon, V.; Eyles, D.; Jones, K.L.; Lyall, K.; Kharrazi, M.; Croen, L.A. Newborn vitamin D levels in relation to autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability: A case–control study in california. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.; Abdel-Rahman, A.A.; Elserogy, Y.M.; Al-Atram, A.A.; Cannell, J.J.; Bjørklund, G.; Abdel-Reheim, M.K.; Othman, H.A.K.; El-Houfey, A.A.; El-Aziz, N.H.R.A.; et al. Vitamin D status in autism spectrum disorders and the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in autistic children. Nutr. Neurosci. 2015, 19, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, S.; Şimşek, Ş.; Camkurt, M.A.; Çim, A.; Çelik, S.B. Association of polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor gene and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. Gene 2016, 588, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basheer, S.; Natarajan, A.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Venkataswamy, M.M.; Ravi, V.; Srinath, S.; Girimaji, S.C.; Christopher, R. Vitamin D status of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Case-control study from India. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desoky, T.; Hassan, M.H.; Fayed, H.M.; Sakhr, H.M. Biochemical assessments of thyroid profile, serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol and cluster of differentiation 5 expression levels among children with autism. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 2397–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altun, H.; Kurutaş, E.B.; Şahin, N.; Güngör, O.; Fındıklı, E. The Levels of Vitamin D, Vitamin D Receptor, Homocysteine and Complex B Vitamin in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2018, 16, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arastoo, A.A.; Khojastehkia, H.; Rahimi, Z.; Khafaie, M.A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Mansouri, M.T.; Yosefyshad, S.; Abshirini, M.; Karimimalekabadi, N.; Cheraghi, M. Evaluation of serum 25-Hydroxy vitamin D levels in children with autism Spectrum disorder. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ansary, A.; Cannell, J.J.; Bjørklund, G.; Bhat, R.S.; Al Dbass, A.M.; Alfawaz, H.A.; Chirumbolo, S.; Al-Ayadhi, L. In the search for reliable biomarkers for the early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: The role of vitamin D. Metab. Brain Dis. 2018, 33, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzghoul, L.; Al-Eitan, L.N.; Aladawi, M.; Odeh, M.; Hantash, O.A. The Association Between Serum Vitamin D3 Levels and Autism Among Jordanian Boys. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 50, 3149–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtourou, M.; Naifar, M.; Grayaa, S.; Hajkacem, I.; Ben Touhemi, D.; Ayadi, F.; Moalla, Y. Vitamin d status in TUNISIAN children with autism spectrum disorders. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 493, S619–S620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, M.G.; Marzulli, L.; Margari, F.; De Giacomo, A.; Gabellone, A.; Giannico, O.V.; Margari, L. Vitamin D Deficiency in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 9292560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şengenç, E.; Kıykım, E.; Saltik, S. Vitamin D levels in children and adolescents with autism. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520934638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shan, L.; Du, L.; Feng, J.; Xu, Z.; Staal, W.G.; Jia, F. Serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 25, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ding, R.; Wang, J. The Association between Vitamin D Status and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Iosif, A.-M.; Angel, E.G.; Ozonoff, S. Association of Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Use With Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder Recurrence in Young Siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Shan, L.; Du, L.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Dong, H.; Yue, X.; Xu, Z.; et al. Clinical improvement following vitamin D3 supplementation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutr. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, H.M.; Sayyah, H.; Youssef, S.; Lotfy, H.; Abdelhamid, I.A.; Elhamed, H.A.A.; Maher, S. Autism and vitamin D. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2015, 22, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadfar, Z.; Abdollahzad, H.; Moludi, J.; Rezaeian, S.; Amirian, H.; Foroughi, A.A.; Nachvak, S.M.; Goharmehr, N.; Mostafai, R. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on core symptoms, serum serotonin, and interleukin-6 in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Nutrition 2020, 79–80, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerley, C.P.; Power, C.; Gallagher, L.; Coghlan, D. Lack of effect of vitamin D3supplementation in autism: A 20-week, placebo-controlled RCT. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazahery, H.; Conlon, C.A.; Beck, K.L.; Mugridge, O.; Kruger, M.C.; Stonehouse, W.; Camargo, C.A.; Meyer, B.J.; Jones, B.; von Hurst, P.R. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 187, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazahery, H.; Conlon, C.A.; Beck, K.L.; Mugridge, O.; Kruger, M.C.; Stonehouse, W.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Meyer, B.J.; Tsang, B.; Jones, B.; et al. A Randomised-Controlled Trial of Vitamin D and Omega-3 Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Treatment of Core Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1778–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, H.; Sohrabi, M.; Taheri, H.; Khodashenas, E.; Movahedi, A. Comparison of the effects of perceptual-motor exercises, vitamin D supplementation and the combination of these interventions on decreasing stereotypical behavior in children with autism disorder. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 66, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolachahi, S.A.; AdibSaber, F.; Elmieh, A. Effects of Vitamin D and/or Aquatic Exercise on IL-1β and IL-1RA Serum Levels and Behavior of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Stud. Med. Sci. 2020, 31, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmar, F.R.; Anderson, G.M. Neurochemical perspectives on infantile autism. In Autism: Nature, Diagnosis, and Treatment; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenecker, B.; Heller, K. The involvement of dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) in stress-induced stereotypies in bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001, 73, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, R.P.; Ames, B.N. Vitamin D hormone regulates serotonin synthesis. Part 1: Relevance for autism. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2398–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Luo, X.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wang, D.; Chen, A. Vitamin D Supplementation is Beneficial for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C. The effect of vitamin D supplementation in treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Song, M.; Huang, X.; Mi, L.; Yang, J.; Cui, X. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2023, 21, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, G.; Henley, K.; Green, J. Autism: Will vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and early childhood reduce the recurrence rate of autism in newborn siblings? Med. Hypotheses 2016, 88, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aagaard, K.; Jepsen, J.R.; Sevelsted, A.; Horner, D.; Vinding, R.; Rosenberg, J.B.; Brustad, N.; Eliasen, A.; Mohammadzadeh, P.; Følsgaard, N.; et al. High-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in pregnancy and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in the children at age 10: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Dang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Exploring the Missing link between vitamin D and autism spectrum disorder: Scientific evidence and new perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojsi, F.; Siciliano, M.; Passaniti, C.; Bisecco, A.; Russo, A.; Lavorgna, L.; Esposito, S.; Ricciardi, D.; Monsurrò, M.R.; Tedeschi, G.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation has no effects on progression of motor dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wang, K.; Hu, T.; Wang, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Vitamin D3 Supplement Attenuates Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption and Cognitive Impairments in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neuromol. Med. 2021, 23, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, Y. Postmortem Studies of Neuroinflammation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 3424–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, S.A.; Smith, O.S.; Adekile, A.D.; Figueiredo, M.S. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and inflammatory cytokines in paediatric sickle cell disease. Cytokine 2017, 96, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cong, X. Genetics of autism spectrum disorder: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noroozi, R.; Dinger, M.E.; Fatehi, R.; Taheri, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Identification of miRNA-mRNA network in autism spectrum disorder using a bioinformatics method. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).