Factors Associated with Worsening Post-Earthquake Psychiatric Symptoms in Patients Receiving Psychiatric Visiting Nurse Services During the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

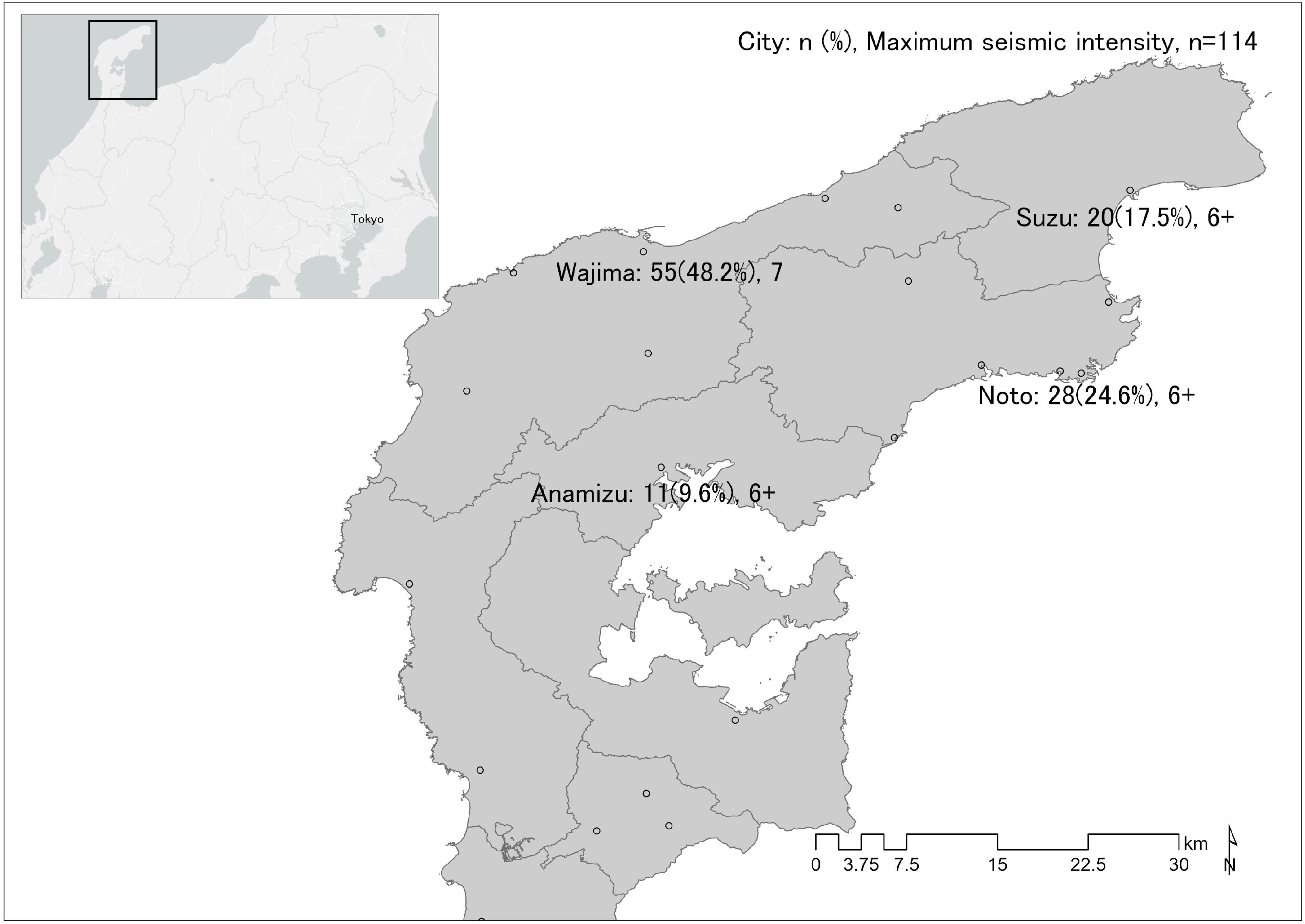

2.1. Target Area and Epicenter of the NPE

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Survey Items

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients Using PVNS

3.2. Residence of PVNS Patients

3.3. Factors Related to the Disaster Situation and Signs of Worsening Mental Health Symptoms in PVNS Patients

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yanagisawa, H.; Abe, I.; Baba, T. What Was the Source of the Nonseismic Tsunami That Occurred in Toyama Bay during the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Bai, L. The 2024 Mj 7.6 Noto Peninsula, Japan Earthquake Caused by the Fluid Flow in the Crust. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2024, 4, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wu, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, Z. Focal Mechanics and Disaster Characteristics of the 2024 M 7.6 Noto Peninsula Earthquake, Japan. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2024, 18, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office a Report on the Damage Caused by the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in 2024. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/updates/r60101notojishin/r60101notojishin/pdf/r60101notojishin_47.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024). (In Japanese).

- Fran, H.N.; Matthew, J.F.; Patricia, J.W.; Christopher, M.B.; Eolia, D.; Krzysztof, K. 60,000 Disaster Victims Speak: Part I. An Empirical Review of the Empirical Literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 2002, 65, 207–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ochi, S.; Murray, V.; Hodgson, S. The Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster: A Compilation of Published Literature on Health Needs and Relief Ac-Tivities, March 2011–September 2012. PLoS Curr. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.C.; Williams, R. Mental Health Services Required after Disasters: Learning from the Lasting Effects of Disasters. Depress. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 970194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, G.; Vasterling, J.J.; Han, X.; Tharp, A.T.; Davis, T.; Deitch, E.A.; Constans, J.I. Preexisting Mental Illness and Risk for Developing a New Disorder After Hurricane Katrina. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, S.; Hodgson, S.; Landeg, O.; Mayner, L.; Murray, V. Disaster-Driven Evacuation and Medication Loss: A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS Curr. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, F.H.-C.; Wu, H.-C.; Chou, P.; Su, C.-Y.; Tsai, K.-Y.; Chao, S.-S.; Chen, M.-C.; Su, T.T.-P.; Sun, W.-J.; Ou-Yang, W.-C. Epidemiologic Psychiatric Studies on Post-Disaster Impact among Chi-Chi Earthquake Survivors in Yu-Chi, Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 61, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Brewin, C.R.; Kaniasty, K.; Greca, A.M.L. Weighing the Costs of Disaster: Consequences, Risks, and Resilience in Individuals, Families, and Communities. Psychol. Sci. Public. Interest. 2010, 11, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nippon Foundation “Reasonable accommodation” in the Employment of People with Disabilities. How Do you Treat People with in-Visible Disabilities? Available online: https://www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/journal/2022/82154 (accessed on 25 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Oe, M.; Nakai, H.; Nagayama, Y. Factors Related to the Willingness of People with Mental Health Illnesses Living in Group Homes to Disclose Their Illness to Supporters during Disaster Evacuation: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa Prefecture Ishikawa’s Topography, Geology and Climate. Available online: https://www.pref.ishikawa.lg.jp/sizen/kankyo/2.html (accessed on 19 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Ishikawa Prefecture Ishikawa Statistical Information. Available online: https://toukei.pref.ishikawa.lg.jp/search/detail.asp?d_id=4898 (accessed on 20 May 2024). (In Japanese).

- Japan Meteorological Agency Seismic Intensity Database Search. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/eqdb/data/shindo/index.html#20240101161022 (accessed on 17 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Wold Health Organization ICD-11. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Overview of ICD-11. Available online: https://jams.med.or.jp/dic/2019material_s2.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare The 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) Has Been Published. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/0000211217.html (accessed on 17 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Administrative Boundary Data from the National Land Numerical Information Download Site. Available online: https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/gml/datalist/KsjTmplt-N03-2024.html (accessed on 18 May 2024). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Municipal Office Data on the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan’s Download Site. Available online: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSexmt9NGhwaTfdqhjAob_ocPtqLU6eH9PDaUU-cy0P8-rD1Dw/viewform?usp=sf_link&usp=embed_facebook (accessed on 4 November 2024). (In Japanese).

- Isikawa Prefecture Crisis Management Division Regarding the Damage Caused by the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in 2024. Available online: https://www.pref.ishikawa.lg.jp/saigai/documents/higaihou_54_0118_1400.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Ohno, H.; Tsutsumi, D.; Furuya, G.; Takiguchi, S.; Ikeda, M.; Miyagi, A.; Miike, T.; Sawa, Y. Sediment-Related Disasters Induced by the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in January 2024. Int. J. Eros. Control. Eng. 2024, 17, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppasri, A.; Kitamura, M.; Alexander, D.; Seto, S.; Imamura, F. The 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake: Preliminary Observations and Lessons to Be Learned. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 110, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba Prefecture Dispatch of the Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team (DPAT) in Response to the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in 2024. Available online: http://www.pref.chiba.lg.jp/shoufuku/press/2023/dpat.html (accessed on 23 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Japan Psychiatric Hospital Association DPAT Activities in Response to the Noto Peninsula Earthquake: Shaping the Future of Psychiatric Care. Available online: https://www.nisseikyo.or.jp/news/topic/detail.php?@DB_ID@=665 (accessed on 23 October 2024). (In Japanese).

- Ichikawa, M.; Ishimine, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Deguchi, H.; Knatani, Y. Healthcare Support Activities and Management in the Event of a Disaster. J. Int. Assoc. P2M 2017, 12, 21–35. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunii, Y.; Usukura, H.; Otsuka, K.; Maeda, M.; Yabe, H.; Takahashi, S.; Tachikawa, H.; Tomita, H. Lessons Learned from Psychosocial Support and Mental Health Surveys during the 10 Years since the Great East Japan Earthquake: Establishing Evidence-Based Disaster Psychiatry. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 76, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Tachikawa, H.; Fukuo, Y.; Takagi, Y.; Tetsuaki, A.; Watari, M. Analysis of Disaster Psychiatric Assistant Team Activity During the Past Four Disasters in Japan. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2019, 34, s100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Fukuo, Y.; Arai, T.; Tachikawa, H. Acute-Stage Mental Health Symptoms by Natural Disaster Type: Consultations of Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Teams (DPATs) in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, H.; Oe, M.; Nagayama, Y. Factors Related to Evacuation Intention When a Level 4 Evacuation Order Was Issued among People with Mental Health Illnesses Using Group Homes in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine 2024, 103, e39428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makwana, N. Disaster and Its Impact on Mental Health: A Narrative Review. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3090–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N. Psychological Impact of Disasters on Children: Review of Assessment and Interventions. World J. Pediatr. 2009, 5, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimori, T. Prolonged Mental Health Problems Due to Natural Disaster: A Study of Hokkaido Nansei-Oki Earthquake Victims. Jpn. J. Personal. 1998, 7, 11–21. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarunzaman, N.K.; Soh, M.C.; Kassim, A.; Othman, S.; Zawawi, A.A.; Nen, Z.M.; Haris, M.Z.I. Vulnerabilities Among Persons with Mental Illness: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Social. Sci. Res. 2022, 4, 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Freedy, J.R.; Simpson, W.M., Jr. Disaster-Related Physical and Mental Health: A Role for the Family Physician. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Munro, A.; Kovats, R.S.; Rubin, G.J.; Waite, T.D.; Bone, A.; Armstrong, B.; Waite, T.D.; Beck, C.R.; Bone, A.; Amlôt, R.; et al. Effect of Evacuation and Displacement on the Association between Flooding and Mental Health Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of UK Survey Data. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e134–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, J.E.; Dabkowski, E.; Ghasemirdekani, M.; Barbagallo, M.S.; James, M.H.; Prokopiv, V.; Wright, W. The Impact of Nature-Led Recovery Initiatives for Individual and Community Health Post Disaster: A Systematic Literature Review. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 38, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.7 (16.9) | ||

| Age group | |||

| 10 s | 4 | 3.5 | |

| 20 s | 4 | 3.5 | |

| 30 s | 21 | 18.4 | |

| 40 s | 21 | 18.4 | |

| 50 s | 25 | 21.9 | |

| 60 s | 16 | 14.0 | |

| 70 s | 18 | 15.8 | |

| 80 s | 5 | 4.4 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 51 | 44.7 | |

| Female | 63 | 55.3 | |

| ICD-11 code 1 | |||

| 6A00 | 5 | 4.4 | |

| 6A02 | 12 | 10.5 | |

| 6A05 | 3 | 2.6 | |

| 6A20 | 52 | 45.6 | |

| 6A60 | 3 | 2.6 | |

| 6A80 | 25 | 21.9 | |

| 6B01 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 6B43 | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 6B60 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 6C40 | 5 | 4.4 | |

| 6E8Y | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 7A00 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 8A22 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Signs of Worsening Mental Health Symptoms | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Total | No | Yes | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p Value | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.7 (16.9) | 0.431 | ||||||

| Age group | <65 years | 85 | 74.6 | 44 | 51.8 | 41 | 48.2 | 0.029 |

| ≥65 years | 29 | 25.4 | 22 | 75.9 | 7 | 24.1 | ||

| Sex | Male | 51 | 44.7 | 33 | 64.7 | 18 | 35.3 | 0.185 |

| Female | 63 | 55.3 | 33 | 52.4 | 30 | 47.6 | ||

| 6A20 code | Other than 6A20 | 62 | 54.4 | 36 | 58.1 | 26 | 41.9 | 0.968 |

| 6A20 | 52 | 45.6 | 30 | 57.7 | 22 | 42.3 | ||

| 6A80 code | Other than 6A80 | 111 | 97.4 | 64 | 57.7 | 47 | 42.3 | 1.000 |

| 6A80 | 3 | 2.6 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | ||

| Number of relocations for evacuation, median (range) | 2.0 (0–5) | 0.881 | ||||||

| Relocations for evacuation | No | 26 | 22.8 | 17 | 65.4 | 9 | 34.6 | 0.379 |

| Yes | 88 | 77.2 | 49 | 55.7 | 39 | 44.3 | ||

| Maximum seismic intensity in prefecture of residence | 6+ | 59 | 51.8 | 36 | 61.0 | 23 | 39.0 | 0.484 |

| 7 | 55 | 48.2 | 30 | 54.5 | 25 | 45.5 | ||

| Presence or absence of cohabitants during the disaster | No | 39 | 34.2 | 24 | 61.5 | 15 | 38.5 | 0.570 |

| Yes | 75 | 65.8 | 42 | 56.0 | 33 | 44.0 | ||

| Evacuated | No | 26 | 22.8 | 17 | 65.4 | 9 | 34.6 | 0.379 |

| Yes | 88 | 77.2 | 49 | 55.7 | 39 | 44.3 | ||

| Presence or absence of cohabitants post-disaster | No | 78 | 68.4 | 44 | 56.4 | 34 | 43.6 | 0.637 |

| Yes | 36 | 31.6 | 22 | 61.1 | 14 | 38.9 | ||

| Use of health and welfare services pre-disaster | No | 50 | 43.9 | 27 | 54.0 | 23 | 46.0 | 0.457 |

| Yes | 64 | 56.1 | 39 | 60.9 | 25 | 39.1 | ||

| Use of health and welfare services post-disaster | No | 71 | 62.3 | 40 | 56.3 | 31 | 43.7 | 0.665 |

| Yes | 43 | 37.7 | 26 | 60.5 | 17 | 39.5 | ||

| Collapse of residence | No | 99 | 86.8 | 59 | 59.6 | 40 | 40.4 | 0.345 |

| Yes | 15 | 13.2 | 7 | 46.7 | 8 | 53.3 | ||

| Stopped using visiting nursing services after the disaster | No | 92 | 80.7 | 49 | 53.3 | 43 | 46.7 | 0.040 |

| Yes | 22 | 19.3 | 17 | 77.3 | 5 | 22.7 | ||

| DPAT intervention | No | 105 | 92.1 | 64 | 61.0 | 41 | 39.0 | 0.034 1 |

| Yes | 9 | 7.9 | 2 | 22.2 | 7 | 77.8 | ||

| Signs of Worsening Mental Health Symptoms | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Total | No | Yes | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p Value | ||

| Number of relocations for evacuation | 0 | 26 | 22.8 | 17 | 65.4 | 9 | 34.6 | 0.881 |

| 1 | 18 | 15.8 | 9 | 50.0 | 9 | 50.0 | ||

| 2 | 38 | 33.3 | 22 | 57.9 | 16 | 42.1 | ||

| 3 | 18 | 15.8 | 9 | 50.0 | 9 | 50.0 | ||

| 4 | 11 | 9.6 | 7 | 63.6 | 4 | 36.4 | ||

| 5 | 3 | 2.6 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | ||

| Total | 114 | 66 | 57.9 | 48 | 42.1 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oe, S.; Nakai, H.; Nagayama, Y.; Oe, M.; Yamaguchi, C. Factors Associated with Worsening Post-Earthquake Psychiatric Symptoms in Patients Receiving Psychiatric Visiting Nurse Services During the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake: A Retrospective Study. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010014

Oe S, Nakai H, Nagayama Y, Oe M, Yamaguchi C. Factors Associated with Worsening Post-Earthquake Psychiatric Symptoms in Patients Receiving Psychiatric Visiting Nurse Services During the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake: A Retrospective Study. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleOe, Shingo, Hisao Nakai, Yutaka Nagayama, Masato Oe, and Chinatsu Yamaguchi. 2025. "Factors Associated with Worsening Post-Earthquake Psychiatric Symptoms in Patients Receiving Psychiatric Visiting Nurse Services During the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake: A Retrospective Study" Psychiatry International 6, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010014

APA StyleOe, S., Nakai, H., Nagayama, Y., Oe, M., & Yamaguchi, C. (2025). Factors Associated with Worsening Post-Earthquake Psychiatric Symptoms in Patients Receiving Psychiatric Visiting Nurse Services During the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake: A Retrospective Study. Psychiatry International, 6(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010014