1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly shaped mental health landscapes, amplifying negative emotions and psychological stressors on a global scale. Social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, emerged as critical spaces for information exchange and emotional expression, where hashtags like #COVIDAnxiety and #PandemicStress reflected widespread public fear and uncertainty. However, while these platforms offered a sense of connection, they also served as conduits for anxiety and fear, exposing users to distressing news updates, rising death tolls, and personal stories of loss and illness. Surveys indicate that approximately 71% of Americans relied on social media for pandemic-related updates [

1], yet many people feel overwhelmed and anxious due to the relentless influx of alarming information [

2,

3,

4]. This reinforces existing evidence linking heavy social media use to heightened anxiety, depression, and other adverse psychological outcomes. Research suggests that the framing of information in social media news or stories can significantly influence emotional responses, particularly during crises. How information is presented on social media shapes how individuals feel, interpret, and react to content [

5]. Consequently, during crises, media frames emphasizing fear, uncertainty, or negative consequences often intensify negative emotional states such as anxiety, anger, and sadness [

6].

While considerable research has examined the role of social media in exacerbating negative emotional states during the pandemic, less is understood about how these emotions shape broader societal responses. This study builds upon existing literature by exploring the dual psychological role of negative emotions in times of crisis—not merely as sources of distress but as potential motivators of cooperative and prosocial behaviors. Theoretical frameworks, such as the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, suggest that discrete emotional responses to risk can trigger diverse psychological and behavioral outcomes. For example, anxiety may act as a catalyst for actions aimed at reducing uncertainty and perceived threats, strengthening social bonds, or contributing to communal well-being. However, the pathways through which social media-driven emotional responses translate into tangible prosocial behaviors remain underexplored.

This study aims to address this gap by examining the complex interplay between social media use, emotional intensification, and behavioral outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it investigates whether and how emotional responses, such as anxiety, anger, and sadness, associated with social media engagement, are linked to public cooperation and prosocial behaviors. Moreover, the study focuses on social interaction—a core function of social media—as a mechanism that fosters emotional responses and behavioral shifts. By analyzing the nuanced roles of specific emotions, particularly anxiety, in shaping public behaviors during crises, this research advances our understanding of the psychological processes underlying collective action.

This research also contributes to the growing body of literature on the pandemic’s psychological consequences, exploring the dual role of social media as both a source of emotional distress and a platform for fostering community resilience and prosocial engagement. The findings have practical implications for mental health interventions and public policy, emphasizing the potential to harness emotional mechanisms to promote cooperative behaviors during public health crises. While COVID-19 has transitioned from a pandemic to an endemic stage, its social, psychological, and behavioral impacts remain highly relevant. Insights from this research extend beyond the pandemic itself, offering valuable applications to other ongoing or emerging global crises, such as climate change, natural disasters, and geopolitical conflicts, where social media significantly influences public behavior and responses. By retrospectively examining the effects of social media use during COVID-19, this study provides empirical evidence on how digital platforms can facilitate—or hinder—collective prosocial behavior during crises, offering important lessons for both researchers and policymakers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media Use and Emotional Responses

Despite the multiple roles social media plays in public crises, one factor that has garnered increasing attention among scholars is how social media use influences behaviors aimed at mitigating risks. Based on the premise that public engagement and cooperation are crucial for reducing public risks, researchers have examined the mechanisms by which social media can enhance cooperative and prosocial actions. While various factors, such as risk perceptions [

7,

8], information [

9], and perceived knowledge [

10], have been identified as mediators of social media’s effects, scholars have increasingly focused on the role of emotions in driving risk-reducing behavior [

11]. Beyond cognitive factors, emotions are believed to exert a powerful influence on people’s judgments and behavioral intentions regarding risks. When individuals experience strong emotions, they often make decisions to mitigate risks [

12,

13] and are motivated to adjust their behaviors to prevent potential negative consequences [

14].

Studies examining the relationship between social media use and emotion show that social media users frequently experience negative emotions during crises [

4,

15]. On platforms like Instagram and TikTok, users often post about their experiences with isolation, depression, and anxiety. As a health crisis signals a significant threat to safety, individuals often respond with strong emotional reactions, leading to more intense expressions of emotions on social media. Gao and colleagues explain that social media use amplifies negative affective responses because disinformation and false reports about COVID-19, prevalent on these platforms, stoke unfounded fears and anxiety [

3]. These negative emotions are also contagious on social media, where the expression of such emotions tends to amplify the emotional responses of other users. Empirical studies also indicate that social media promotes the social sharing of emotions, particularly in times of crisis, leading people to experience more negative emotions [

16,

17].

Although several theories have been proposed to explore the relationship between media use and emotional responses, appraisal theories of emotion [

18,

19,

20] offer a valuable framework for understanding the connection between social media use and emotional experiences during crises. According to appraisal theories, emotions arise from individuals’ evaluations of their environment in relation to their goals, and these appraisals lead to specific emotional responses. For instance, if an individual appraises a situation as threatening and uncertain, they may feel anxiety, whereas if they attribute the situation to the fault of others, they may feel anger. On the other hand, if an individual perceives an irrevocable loss resulting from the situation, they are likely to experience sadness or depression [

18]. As a result, different appraisals of events give rise to specific emotions, as individuals interpret situations uniquely based on their expectations, beliefs, and perceived level of control.

Given the vast amount of information and personal stories shared about the pandemic on social media, users are exposed to increased opportunities to evaluate the crisis, potentially leading to heightened emotional reactions. In particular, the cognitive appraisal process, through which individuals assess the severity and personal relevance of events, is heavily influenced by the type of information shared on social media. Specifically, the abundance of pandemic-related content on social media can be associated with particular negative emotions. For instance, when users repeatedly encountered content framing COVID-19 as unpredictable and uncontrollable, as seen in widespread reports of shifting infection rates, evolving virus variants, and inconsistent public health guidelines, they are likely to appraise the situation as an uncertain threat, thereby triggering anxiety. Furthermore, personal stories shared on social media often amplify narratives of irreversible loss, including reports of lives and livelihoods destroyed, which reinforces the belief that the pandemic’s damage is permanent and, in turn, fosters sadness. Additionally, social media discussions about the pandemic have highlighted external sources of blame for the crisis, such as government failures or foreign entities, which can intensify anger by attributing responsibility to factors outside an individual’s control. Thus, it is postulated that social media use not only fosters emotional engagement with the pandemic but also shapes the way individuals appraise the crisis, leading to discrete emotional responses like anxiety, sadness, and anger.

Empirical studies also suggest that social media use during the pandemic can promote these feelings. For example, a study found that social media amplified negative emotions, including anxiety and depression, among users due to exposure to alarming news updates and content that heightened fears related to the pandemic [

21]. Lu and Hong demonstrated that social media platforms were utilized to express and amplify negative emotions during the pandemic [

22]. Their findings suggest that, particularly during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, social media intensifies negative emotions through mechanisms such as emotional contagion. In addition, Yang and Tian [

23] investigated how interaction-focused social media use (i.e., communal engagement; [

24]) influenced emotions, self-efficacy, perceived knowledge, and perceptions of fake news regarding COVID-19. Their findings revealed that communal engagement on social media was associated with increased anxiety, fear, and worry, as well as heightened third-person perception.

Based on appraisal theories of emotion and existing research on the relationship between social media use and emotional responses, it is hypothesized that social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic will intensify emotional responses. Specifically, it is expected that increased social media interaction will elicit stronger emotional experiences, such as anxiety, anger, and sadness, in response to the pandemic.

Accordingly, the first hypothesis is proposed.

H1. Social media interaction will be positively related to emotional responses (anxiety, anger, and sadness) to COVID-19.

2.2. Social Media Use and Behavioral Responses to Risk

Social media’s role extends beyond emotional engagement to shaping behaviors during crises. Research has demonstrated that social media use can encourage cooperative behaviors, such as compliance with government policies [

25]. This is often attributed to the accessibility of timely information, which allows individuals to remain informed about ongoing health guidelines and public safety measures. Social media platforms provide a direct line of communication between government agencies and the public, fostering an environment where people can stay updated on evolving policies and regulations. Furthermore, the widespread dissemination of information on platforms like Facebook and Twitter has been shown to boost collective awareness and shape social norms [

26], reinforcing the importance of following government mandates during crises.

Another way social media may promote public cooperation is by cultivating a deep sense of connectedness through shared interactions and experiences. Indeed, social interactions online increase opportunities for users to understand others’ emotions and develop empathy [

27]. These interactions contribute to a sense of social connectedness [

28] and the quality of online relationships [

29], potentially intensifying emotional reactions to the perceived risks of the pandemic. Additionally, unlike traditional news media, social media interactions often involve more personalized information, coming directly from one’s network members, which can deepen the emotional impact of events [

30]. Studies have shown that social media interactions help users comprehend others’ experiences and emotions related to the crisis, fostering feelings of empathy [

31,

32]. Consequently, these feelings of connectedness and belonging, associated with social media use, may facilitate cooperative intentions.

While previous research has explored the link between social media use and cooperative behaviors, the emphasis has often been on individual-level actions, such as precautionary behaviors [

33], adherence to government measures [

34], or support for policy interventions [

35]. However, beyond simply supporting or complying with authority-imposed measures, engaging in prosocial behaviors embodies a proactive and critical public response to risk. Prosocial behavior in risk contexts includes actions such as volunteering within the community, offering assistance to those affected by the risk, or donating resources to mitigate the threat.

Building on previous research, this study expects that behaviors with broader social impacts, such as prosocial behaviors, may result from discrete emotions induced by social media use. Empirical evidence also suggests that prosocial behaviors can function as a valuable outlet for alleviating negative emotional experiences [

36]. Engaging in prosocial behavior has been widely recognized as a coping mechanism, helping individuals alleviate psychological and physiological stress triggered by perceived threats [

36]. Therefore, individuals experiencing higher levels of negative emotions may be more inclined to engage in actions that mitigate these emotions. Drawing on insights gained from previous research, the second hypothesis is formulated.

H2a. Social media interaction will be positively related to cooperative behavior (e.g., support for government policies).

H2b. Social media interaction will be positively related to prosocial behavior (e.g., volunteering).

2.3. Emotion as a Mediator

Emotions play a pivotal role in shaping behavioral responses to risk. When individuals experience negative emotions, particularly those triggered by threats to their lives or health, they are likely to take protective actions. Several theories explain the connection between emotion and action. For instance, the feelings-as-information model posits that people use emotions as a source of information when making decisions, especially when they lack the motivation or ability to deliberate on an issue [

37]. Consequently, specific emotions lead individuals to interpret messages in an affect-consistent manner, prompting them to engage in corresponding behaviors. Similarly, appraisal theories of emotion [

18,

19,

20] propose that discrete emotions, which arise from particular appraisals of a situation, are characterized by distinct action tendencies [

38]. For instance, anger motivates individuals to approach and confront a problem, while anxiety encourages actions to avoid or mitigate the threat, and sadness or depression leads to introspection and a desire for reassurance [

18]. Therefore, emotional responses to risk play a critical role in shaping risk judgments and behaviors [

8,

39].

During crises, emotions are expected to trigger behaviors that reduce perceived threats, such as increased support for government policies and other prosocial behaviors. Specifically, feeling anxiety about COVID-19 may lead individuals to support policies aimed at addressing the risk, as these measures can help prevent or mitigate the perceived threat. Feeling anger toward the pandemic might motivate people to take proactive actions, such as advocating for solutions or supporting policies that aim to reduce the risk. Similarly, individuals experiencing sadness or depression may seek relief and protection, driving them to support policies designed to safeguard the public. These same emotions may also steer prosocial behaviors—anxiety, for example, could promote prosocial actions, as individuals strive to ensure both personal and communal safety [

40]. Anger and sadness, like anxiety, can also lead to prosocial behavior during crises. Anger, when directed towards perceived injustices or external factors responsible for the crisis, can motivate individuals to advocate for change, engage in activism, or support policies that hold responsible entities accountable [

41]. It can drive a desire to correct the wrongs and protect others from similar threats in the future [

42]. On the other hand, sadness can evoke feelings of empathy and compassion for those affected by the crisis [

43]. Experiencing sadness may push individuals to offer support, donate resources, or volunteer to alleviate suffering. The introspective nature of sadness often leads to a desire to create connections with others, fostering communal action aimed at overcoming adversity together [

42]. These emotions, therefore, can serve as powerful motivators for collective efforts to mitigate the impact of a crisis.

Thus, emotions triggered by social media use are likely to mediate the relationship between social media engagement and cooperative or prosocial behaviors. This notion is well supported by empirical evidence. For instance, anxiety and worry are powerful predictors of precautionary behaviors, often surpassing factors such as risk perception [

44]. Peters and colleagues found that anxiety, more than cognitive risk perception, predicted actions like donating or volunteering during crises, which benefit others [

44]. Similarly, anger has been associated with increased support for policies [

45] and a higher likelihood of contributing to causes that aim to mitigate harm [

46]. Sadness has been associated with increased support for protective measures [

47]. Furthermore, Stellar and colleagues suggest that sadness can foster empathy and strengthen prosocial tendencies, encouraging individuals to take action to alleviate the suffering of others [

48].

Taken together, this study anticipates that feelings of anxiety, anger, and sadness related to COVID-19 will positively correlate with prosocial behaviors and support for policies aimed at reducing the threat. However, it is important to acknowledge that previous research indicates these emotions may not consistently lead to the anticipated prosocial outcomes. For example, while some studies propose that anger can facilitate prosocial behaviors like compensating victims [

49], others highlight that anger may lead to more antagonistic or aggressive actions [

50]. Similarly, sadness has been shown to enhance compassion and prosocial tendencies [

48], yet it has also been linked to passivity or inaction [

51]. This suggests that the relationship between these emotions and behaviors is more complex than initially expected.

Given the mixed findings, the impact of these specific emotions on cooperative and prosocial behaviors, particularly in the context of public health risks, remains uncertain. As a result, this study frames the exploration of these emotional influences as a research question, rather than a definitive hypothesis, to better capture the nuanced and potentially divergent effects of these emotions on behavior.

H3. Social media interaction will be positively related to cooperative and prosocial behaviors, mediated by emotional responses to COVID-19 (anxiety, anger, and sadness).

RQ1: Are there differences between anxiety, anger, and sadness in their impact on eliciting cooperative and prosocial behaviors?

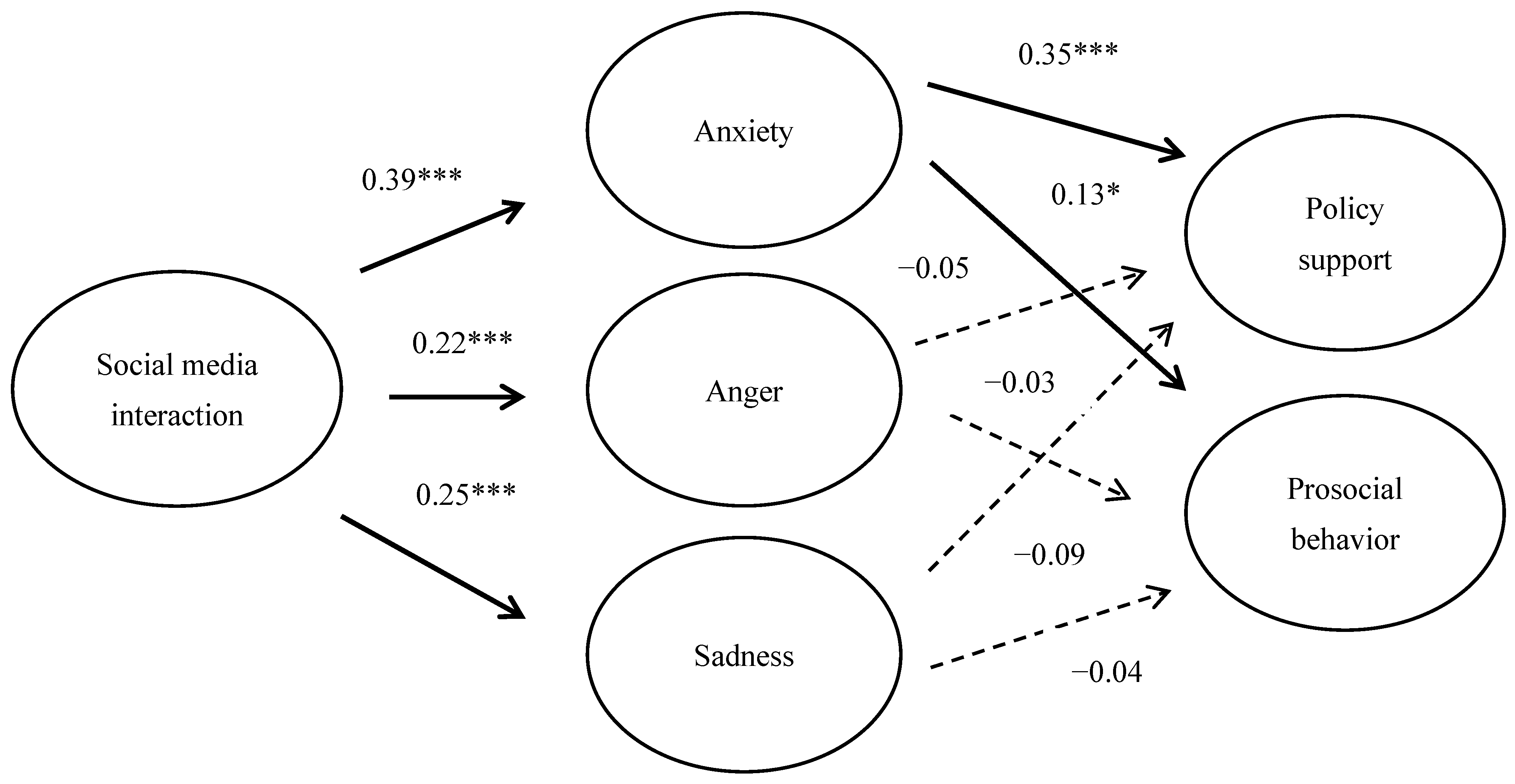

The conceptual model of the study is presented in

Figure 1.

5. Discussion

Building on prior research examining the impact of social media on public responses to risk, this study aimed to explore how social media use influences emotional reactions to risk and how these emotional responses subsequently impact cooperative and prosocial behaviors. While previous studies often highlight the negative mental health consequences of emotions [

3,

15], our findings suggest a more nuanced perspective: these negative emotions, when amplified by social media interaction, can also have a positive societal impact. This shift in focus reveals that, although negative emotions such as anxiety are often viewed as detrimental to individual mental health, they may serve as catalysts for collective action during public crises. By fostering a sense of interconnectedness and empathy, social media enables users to not only feel the weight of societal risks but also to channel these emotions into behaviors that benefit the broader community.

The finding that social media interaction amplifies emotional responses to risk is especially important when considering the phenomenon of optimistic bias, wherein individuals believe they are less likely than others to be affected by negative events [

55]. Previous research suggests that this discrepancy between personal and societal risk perceptions can demotivate people from taking public action to mitigate risks [

56,

57]. By amplifying emotional responses, social media may play a critical role in helping people recognize the personal relevance of risks, thereby challenging the belief that risks only affect others. This heightened emotional engagement can, in turn, lead to greater cooperation and efforts to reduce risks. Given the crucial role that emotions play in mobilizing public responses to risk [

39], this study extends existing research by demonstrating that social media can be used not only to regulate emotions during crises [

31] but also to amplify emotional responses that prompt public action.

Furthermore, the study found that anxiety was a strong predictor of prosocial behavior and cooperation with government measures. This is consistent with research showing that anxiety positively influences risk-reducing behaviors [

58,

59]. Importantly, anxiety not only influenced individual-level risk-related behaviors (e.g., supporting policies) but also spurred social-level behaviors with prosocial implications (e.g., volunteering, donating). Contrary to some previous research suggesting that anxiety might inhibit political or civic participation [

60], the findings of this study indicate that anxiety, when induced by active social media interaction, has the potential to foster public engagement in prosocial activities.

The finding that sadness was marginally negatively associated with policy support raises further questions. Contrary to the hypothesis, individuals who felt sadness about the risk were less likely to support policies aimed at mitigating it. This aligns with the idea that sadness is often characterized as an inaction-oriented emotion [

18]. However, considering that other studies suggest that sadness can increase preferences for welfare policies [

61] or foster greater intentions to help others [

62], these mixed findings imply that the influence of sadness on behavior may depend on other relevant factors such as the type of risk (e.g., natural vs. human-made) and individual traits (e.g., empathy levels).

The lack of a significant relationship between anger and behavioral responses is somewhat surprising, given prior research indicating that anger can shape policy preferences and actions in various risk contexts [

45,

46]. One possible explanation is that anger may be more influential in contexts where the core action tendency—blaming or punishing—can effectively reduce the perceived threat. In the case of COVID-19, a public health crisis, blaming others may not translate into meaningful actions that mitigate the risk, which could explain why anger did not drive prosocial behavior in this study. Future research should further investigate the circumstances under which different emotions promote cooperative or prosocial behaviors.

One important finding of this study is that social media interaction itself was positively associated with greater support for policies and prosocial behaviors, independent of the mediating role of emotions. This supports existing literature suggesting that the inherent characteristics of social media—such as connectedness and interactivity—can foster mutual understanding and empathy [

27]. By enabling users to connect with others and understand their emotions [

63], social media may promote prosocial behaviors during times of risk. Future studies could explore which specific aspects of social media use (e.g., frequency of exposure to crisis-related content, engagement with misinformation, interactions within supportive online communities, or the use of emotion-laden narratives) are most closely linked to emotional, behavioral, and cognitive effects, such as changes in risk perception.

The findings of this study also showed that self-efficacy was associated with reduced emotional responses to COVID-19. Self-efficacy, defined as the belief that one can effectively manage or mitigate risks [

64], is often viewed as a critical driver of action. However, in this case, higher self-efficacy may have reduced concern or anxiety about the risk, potentially leading to lower engagement in risk mitigation efforts. This aligns with research suggesting that self-efficacy can sometimes result in overconfidence [

65], thereby reducing the likelihood of generating emotional responses. Future research should further explore the conditions under which self-efficacy fosters positive action versus when it leads to complacency.

5.1. Implications

This study adds to the growing research on how social media shapes public emotional responses to risks and encourages prosocial behavior. While much of the existing literature emphasizes the negative effects of emotions like anxiety and sadness—particularly in terms of their contribution to mental health disorders—this study offers a more nuanced perspective. While negative emotions can exacerbate psychological distress and mental health issues, such as increased stress and emotional instability, when these emotions are channeled through socially interactive and empathetic uses of social media, they have the potential to yield positive societal outcomes. Rather than framing these emotions as solely harmful, the findings suggest they can be channeled into fostering prosocial actions, including volunteering, donating, and supporting public health policies. Furthermore, considering the persistent gap between personal and general risk perceptions [

7], this study highlights how social media may help bridge that gap by providing personalized, interpersonal avenues for risk communication. This helps individuals recognize the relevance of societal risks to their own lives, thereby promoting greater cooperation and public engagement.

In addition, the findings can be understood and their implications extended within a broader context. Similar mechanisms—such as the role of social media in amplifying emotions and influencing prosocial behaviors—are likely to be relevant in other crises, including natural disasters, economic crises, or geopolitical conflicts. These events often generate widespread emotional responses and collective actions facilitated by digital platforms, making them comparable to the dynamics observed during the pandemic.

From a practical perspective, the findings of this study provide valuable insights for both mental health practitioners and public health policymakers. Anxiety, often seen as a mental health challenge, emerges in this study as a dual-faceted emotion that can motivate cooperative and prosocial actions. This nuanced understanding highlights opportunities for interventions that leverage anxiety constructively, rather than solely mitigating its effects. For instance, mental health interventions could focus on anxiety management techniques that channel this emotion toward productive actions, such as volunteering, donating, or compliance with health guidelines, rather than allowing it to escalate into maladaptive stress or panic. In the public health domain, campaigns could strategically use messages that evoke manageable levels of anxiety, emphasizing collective responsibility and achievable actions. Indeed, campaigns have traditionally relied on fear appeals to encourage compliance with public health measures; however, such messaging can backfire by eliciting avoidance or withdrawal behaviors [

66]. This study suggests that focusing on anxiety, rather than fear, may encourage greater public engagement without the risk of these unintended negative consequences. By inducing a sense of concern and responsibility, anxiety might serve as a more effective emotional trigger for fostering cooperation and prosocial actions.

Furthermore, the study’s findings suggest that social media platforms could be optimized to facilitate emotional engagement more effectively. Design features that promote emotional sharing, community-building, and empathetic understanding could enhance the public’s willingness to cooperate during crises. For example, platforms could integrate features that highlight community-driven support systems or allow users to share their personal experiences with public health risks, making the threat feel more immediate and relatable. These design elements could create a more engaging and interactive environment that encourages users to take collective action in response to societal risks. In a broader context, policymakers and social media companies could collaborate to leverage these insights, ensuring that digital spaces are designed not only for information dissemination but also for emotional and behavioral engagement. By fostering a sense of shared responsibility and empathy through tailored social media interactions, these platforms can play a crucial role in addressing public health risks and encouraging cooperative behaviors that contribute to the overall well-being of society.

Finally, the study underscores the need for systemic support for mental health during crises. Governments and healthcare providers should allocate resources to expand access to mental health services, particularly for individuals disproportionately affected by emotional distress linked to social media use. This includes enhancing crisis hotline availability and training mental health professionals to address the unique challenges posed by digital engagement during crises.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides valuable insights into the role of social media in shaping emotional responses and fostering prosocial behavior, it is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data makes it difficult to establish clear causal relationships between social media use, emotional responses, and prosocial behavior. Future research could benefit from using longitudinal or experimental designs to better understand the directionality and potential causality between these variables. For example, a longitudinal study could track changes in social media use, emotional states, and prosocial behaviors over time, providing a clearer picture of how these factors interact during crises.

Second, this study focused primarily on negative emotional responses (anxiety, anger, sadness) and their potential for prosocial outcomes. However, future research should explore a wider range of emotions, including positive emotions such as hope or compassion, which may also play important roles in shaping prosocial behavior. Examining how both positive and negative emotions interact in driving behavior would offer a more comprehensive understanding of social media’s emotional impact. Additionally, the study used self-reported data for measuring emotions and behaviors, which can introduce biases such as social desirability or recall errors. Future studies could incorporate more objective measures, such as physiological indicators of emotion (e.g., heart rate) or behavioral tracking data from social media platforms, to complement self-reported responses and provide a more robust assessment of the emotional and behavioral impacts of social media use.

In addition, the sample for this study was non-probabilistic, meaning that participants were not randomly selected, which limits the representativeness of the sample. Consequently, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other contexts, populations, or topics with confidence. This sampling method might have introduced biases, as participants self-selected into the study, potentially skewing the results based on the characteristics of those more inclined to participate. Future research using probabilistic sampling methods or a more diverse and representative sample is recommended to enhance the generalizability and applicability of the findings.

This study was conducted during the endemic stage of COVID-19, raising questions about the continued relevance of the pandemic’s psychological impact on the sample. Although the design and sample of this study do not allow for a direct and explicit examination of the pandemic’s immediate psychological impact, its consequences likely continue to shape people’s emotional and behavioral responses. The participants, having lived through the pandemic, may still experience residual effects, such as heightened anxiety, sadness, and shifts in social behaviors. These lingering emotions provide a valuable lens for understanding how individuals process and respond to crises, even after the immediate threat has subsided. Nevertheless, considering that the psychological effects of the pandemic may differ between its acute phase and the post-pandemic period [

67], future research could benefit from employing a longitudinal design to track emotional and behavioral shifts over time. Such an approach would offer a clearer understanding of both the short-term and long-term effects of the pandemic. Additionally, broadening the scope to include comparative analyses with other crises could yield deeper insights into the universality or specificity of these findings. These approaches would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between social media, emotions, and behavioral responses in crisis contexts.

Relatedly, the participants’ responses in this study likely reflect a combination of their current perceptions of COVID-19 as a relevant event and their memories or past experiences of the pandemic [

8]. This possibility presents an important caveat when interpreting the study’s findings. Future research could benefit from directly assessing participants’ perceptions of COVID-19’s relevance at the time of data collection, allowing for a clearer distinction between the influence of present perceptions and past experiences. The emotional responses captured in this study are likely shaped by the lingering effects of the pandemic or retrospective reflections, rather than acute emotional states driven by the urgency of addressing the crisis. Future research that differentiates between risk behaviors exhibited during the peak of the pandemic and those observed over time could provide valuable insights into the evolution of emotional and behavioral responses across different stages of a crisis.

The effects of social media use are also likely influenced by individual differences, such as information-processing abilities, pre-existing risk perceptions, or emotional tendencies. These personal characteristics can moderate the effects of social media on risk-related behaviors. For instance, individuals with greater information-processing skills may better filter misinformation, while those with higher risk perceptions may be more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors when exposed to emotionally charged content. Future research should explore how these individual characteristics interact with social media use to affect emotional and behavioral responses. Lastly, this study examined social media use in a generalized manner, without differentiating between specific platforms or types of engagement. Social media platforms vary in their design, affordances, and user interactions, all of which may influence emotional experiences and behaviors differently. Future research could explore how various types of social media platforms uniquely influence emotions and behaviors during crises, providing more nuanced insights into the intricate relationship between social media use, emotional responses, and public actions in times of crisis.