Association between Neuroticism and Premenstrual Affective/Psychological Symptomatology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Sample

2.3. Study Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

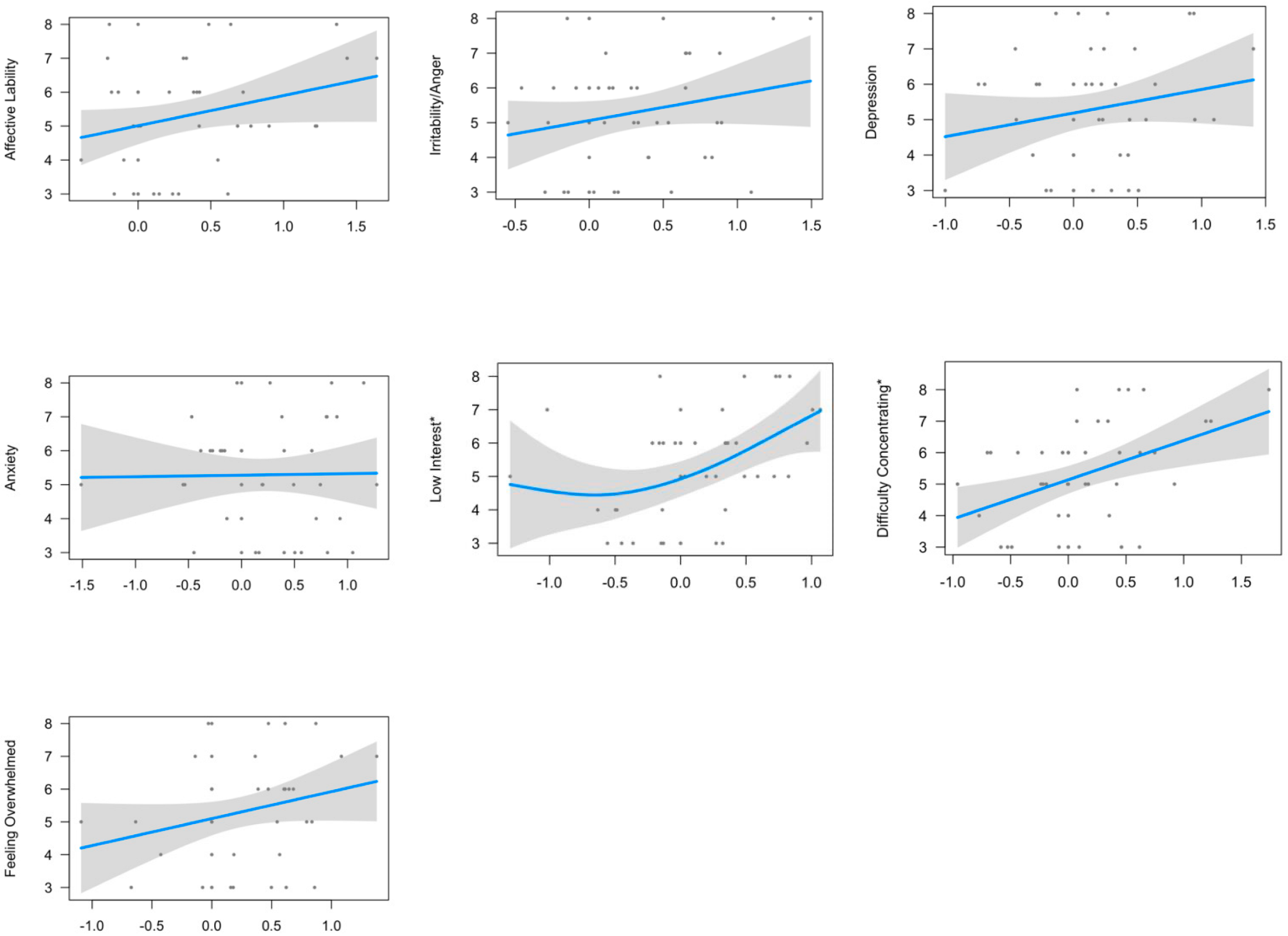

3.2. Relationship between Neuroticism-Anxiety and Premenstrual Symptomatology

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DSM-5 Symptoms | DRSP Question | Inclusion in Present Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Marked affective lability (e.g., mood swings, feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection *,# | 5. Had mood swings (e.g., suddenly felt sad or tearful) DRSP 6. Was more sensitive to rejection or my feelings were easily hurt | Included as affective symptom |

| 2. Marked irritability or anger or increased interpersonal conflicts *,# | 7. Felt angry, irritable 8. Had conflicts or problems with people | Included as affective symptom |

| 3. Marked depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts *,# | 1. Felt depressed, sad, down, or blue 2. Felt hopeless 3. Felt worthless or guilty | Included as affective symptom |

| 4. Marked anxiety, tension, and/or feelings of being keyed up or on edge *,# | 4. Felt anxious, tense, keyed up, or on edge | Included as affective symptom |

| 5. Decreased interest in usual activities (e.g., work, school, friends, hobbies) | 9. Had less interest in usual activities (e.g., work, school, friends, hobbies) | Included as psychological symptom |

| 6. Subjective difficulty in concentration | 10. Had difficulty concentrating | Included as psychological symptom |

| 7. A sense of being overwhelmed or out of control # | 16. Felt overwhelmed or that I could not cope 17. Felt out of control | Included as psychological symptom |

| 8. Marked change in appetite; overeating; or specific food cravings | 12. Had increased appetite or overate 13. Had cravings for specific foods | Not included—behavioral symptom |

| 9. Hypersomnia or insomnia | 14. Slept more, took naps, found it hard to get up when intended 15. Had trouble getting to sleep or staying asleep | Not included—behavioral symptom |

| 10. Lethargy, easy fatigability, or marked lack of energy | 11. Felt lethargic, tired, fatigued, or had a lack of energy | Not included—physical symptom |

| 11. One physical symptom (for example, breast tenderness) | 18. Had breast tenderness 19. Had breast swelling, felt bloated, or had weight gain 20. Had headache 21. Had joint or muscle pain | Not included—physical symptom |

| Demographic Variable | Category | Diagnostic Category | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMDD (n = 7) | PMS (n = 21) | Healthy (n = 17) | |||

| Age | 25.1 (3.89) | 25 (5.34) | 27 (4.68) | 0.27 | |

| Race | White | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.77 |

| Black or African American | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Asian | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.11 | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| More than one race | 0.02 | 0 | 0.02 | ||

| Unknown/Do not want to specify | 0 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.52 |

| Non-Hispanic | 0.11 | 0.40 | 0.29 | ||

| Unknown/Do not want to specify | 0.02 | 0 | 0.02 | ||

| Student Status | Yes | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.61 |

| No | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.24 | ||

| Marital Status | Single | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.99 |

| Married | 0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Income | Less than $20,000 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.11 | ||

| $35,000–$49,999 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||

| $50,000–$74,999 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | ||

| 75,000 or more | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | ||

| Age of Menarche | 12.4 (1.14) | 12.1 (0.93) | 11.7 (1.41) | 0.21 | |

| BMI | 24.0 (3.25) | 24.9 (5.45) | 24.3 (3.73) | 0.99 | |

References

- Ormel, J.; Jeronimus, B.F.; Kotov, R.; Riese, H.; Bos, E.H.; Hankin, B.; Rosmalen, J.G.; Oldehinkel, A.J. Neuroticism and common mental disorders: Meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Friedman, H.S. Neuroticism and health as individuals age. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2019, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eysenck, H.J. Intelligence assessment: A theoretical and experimental approach. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1967, 37, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A.; Higgins, C.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Barrick, M.R. The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 621–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Jr, P.T.; McCrae, R.R.; Zonderman, A.B.; Barbano, H.E.; Lebowitz, B.; Larson, D.M. Cross-sectional studies of personality in a national sample: II. Stability in neuroticism, extraversion, and openness. Psychol. Aging 1986, 1, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T.; Terracciano, A.; Parker, W.D.; Mills, C.J.; De Fruyt, F.; Mervielde, I. Personality trait development from age 12 to age 18: Longitudinal, cross-sectional, and cross-cultural analyses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Mroczek, D. Personality trait change in adulthood. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 17, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, P.J.; Martinez, P.E.; Nieman, L.K.; Koziol, D.E.; Thompson, K.D.; Schenkel, L.; Wakim, P.G.; Rubinow, D.R. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms following ovarian suppression: Triggered by change in ovarian steroid levels but not continuous stable levels. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, T.; Rubenstein, B.B. The correlations between ovarian activity and psycho-dynamic processes. II. The menstrual phase. Psychosom. Med. 1939, 1, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslantaş, H.; Abacigil, F.; Çinakli, Ş. Relationship between premenstrual syndrome and basic personality traits: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2018, 136, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Mar Fernández, M.; Regueira-Méndez, C.; Takkouche, B. Psychological factors and premenstrual syndrome: A Spanish case-control study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingnell, M.; Comasco, E.; Oreland, L.; Fredrikson, M.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. Neuroticism-related personality traits are related to symptom severity in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and to the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphism 5-HTTPLPR. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2010, 13, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adewuya, A.; Loto, O.; Adewumi, T. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder amongst Nigerian university students: Prevalence, comorbid conditions, and correlates. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2008, 11, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, S.A.; Heath, A.; Martin, N. Genetic and environmental influences on premenstrual symptoms in an Australian twin sample. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Vo, H.; Huo, L.; Roca, C.; Schmidt, P.J.; Rubinow, D.R. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR-1) associations with psychological traits in women with PMDD and controls. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmalenberger, K.M.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A.; Surana, P.; Rubinow, D.R.; Girdler, S.S. Predictors of premenstrual impairment among women undergoing prospective assessment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A cycle-level analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halbreich, U.; Borenstein, J.; Pearlstein, T.; Kahn, L.S. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlert, S.; Hartlage, S. A design for studying the DSM-IV research criteria of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.L.; Swindle, R.W. Premenstrual symptom severity: Impact on social functioning and treatment-seeking behaviors. J. Women’s Health Gend.-Based Med. 2000, 9, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.W. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Definitions and diagnosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenoğlu, R.; Sözbir, Ş.Y. Are premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhea related to the personality structure of women? A descriptive relation-seeker type study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1992, 13, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Coleman, G.; Stojanovska, C. Relationship between the NEO personality inventory revised neuroticism scale and prospectively reported negative affect across the menstrual cycle. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 22, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Qiao, M.; An, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Song, C.; Wei, F.; Yu, Y.; Gong, T.; Gao, D. Brain reactivity to emotional stimuli in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and related personality characteristics. Aging 2021, 13, 19529–19541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, K.; Diener, E.; Fujita, F.; Pavot, W. Extraversion and neuroticism as predictors of objective life events: A longitudinal analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutton, D.; Pelton, L.E.; Lumpkin, J.R. Personality characteristics and salespeople’s choice of coping strategies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperribai, L.; Alonso-Arbiol, I.; Balluerka, N.; Claes, L. Development of a screening instrument to assess premenstrual dysphoric disorder as conceptualized in DSM-5. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 88, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hastie, T.J.; Tibshirani, R.J. Generalized Additive Models; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott, J.; Nee, J.; Harrison, W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): Reliability and validity. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2006, 9, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingnell, M.; Bannbers, E.; Wikstrom, J.; Fredrikson, M.; Sundstrom-Poromaa, I. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and prefrontal reactivity during anticipation of emotional stimuli. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Pang, Y.; Duan, G.; Liu, H.; Liao, H.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Wen, D.; et al. Larger volume and different functional connectivity of the amygdala in women with premenstrual syndrome. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 1900–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis-Ortiz, S.; Corsi-Cabrera, M. Sustained attention is favored by progesterone during early luteal phase and visuo-spatial memory by estrogens during ovulatory phase in young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2008, 33, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohda, S.; Suzuki, K.; Igari, I. Relationship between the menstrual cycle and timing of ovulation revealed by new protocols: Analysis of data from a self-tracking health app. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aluja, A.; Rossier, J.; García, L.F.; Angleitner, A.; Kuhlman, M.; Zuckerman, M. A cross-cultural shortened form of the ZKPQ (ZKPQ-50-cc) adapted to English, French, German, and Spanish languages. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults. 1983. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t06496-000 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. Beck depression inventory (BDI). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bosc, M.; Dubini, A.; Polin, V. Development and validation of a social functioning scale, the Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997, 7, S57–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, K.; Constable, R.T.; Canli, T. Amygdala gray matter concentration is associated with extraversion and neuroticism. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1905–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.I.; Williams, D.; Feczko, E.; Barrett, L.F.; Dickerson, B.C.; Schwartz, C.E.; Wedig, M.M. Neuroanatomical correlates of extraversion and neuroticism. Cereb. Cortex 2006, 16, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sollberger, M.; Stanley, C.M.; Wilson, S.M.; Gyurak, A.; Beckman, V.; Growdon, M.; Jang, J.; Weiner, M.W.; Miller, B.L.; Rankin, K.P. Neural basis of interpersonal traits in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2812–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adelstein, J.S.; Shehzad, Z.; Mennes, M.; DeYoung, C.G.; Zuo, X.-N.; Kelly, C.; Margulies, D.S.; Bloomfield, A.; Gray, J.R.; Castellanos, F.X. Personality is reflected in the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Y.; Craig, A.; Boord, P.; Connell, K.; Cooper, N.; Gordon, E. Personality traits and its association with resting regional brain activity. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2006, 60, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaušovec, N.; Jaušovec, K. Personality, gender and brain oscillations. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2007, 66, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutin, A.R.; Beason-Held, L.L.; Resnick, S.M.; Costa, P.T. Sex differences in resting-state neural correlates of openness to experience among older adults. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 2797–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheng, T.; Gheytanchi, A.; Aziz-Zadeh, L. Default network deactivations are correlated with psychopathic personality traits. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R. Überblick über Reliabilitäts-und Validitätsbefunde von klinischen und außerklinischen Selbst-und Fremdbeurteilungsverfahren. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlage, S.A.; Freels, S.; Gotman, N.; Yonkers, K. Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Secondary Analyses of Relevant Data Sets. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dennerstein, L.; Lehert, P.; Bäckström, T.C.; Heinemann, K. Premenstrual symptoms—Severity, duration and typology: An international cross-sectional study. Menopause Int. 2009, 15, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Harvey, K.; McCabe, C.; Reynolds, S. Understanding anhedonia: A qualitative study exploring loss of interest and pleasure in adolescent depression. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinckier, F.; Gourion, D.; Mouchabac, S. Anhedonia predicts poor psychosocial functioning: Results from a large cohort of patients treated for major depressive disorder by general practitioners. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhang, H.; He, Q.; Guo, L.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Fan, B.; Lu, C.; Mclntyer, R. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: A meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, R.S.; Bennett, D.A.; de Leon, C.F.M.; Bienias, J.L.; Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A. Distress proneness and cognitive decline in a population of older persons. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; Tamir, M. Neuroticism as mental noise: A relation between neuroticism and reaction time standard deviations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchek, J.M.; Balota, D.A.; Storandt, M.; Larsen, R. The power of personality in discriminating between healthy aging and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2007, 62, P353–P361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, R.S.; Arnold, S.E.; Schneider, J.A.; Li, Y.; Bennett, D.A. Chronic distress, age-related neuropathology, and late-life dementia. Psychosom. Med. 2007, 69, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, E.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Smyth, J.M.; Almeida, D.M.; King, H.A. Intrusive thoughts mediate the association between neuroticism and cognitive function. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Domain | DSM-5 Symptoms | DRSP Question |

|---|---|---|

| Affective | Marked affective lability (e.g., mood swings; feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection) | DRSP 5. Had mood swings (e.g., suddenly felt sad or tearful) |

| Marked irritability or anger or increased interpersonal conflicts | DRSP 7. Felt angry, irritable | |

| Marked depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts | DRSP 1. Felt depressed, sad, ‘down’ or blue | |

| Marked anxiety, tension, and/or feelings of being keyed up or on edge | DRSP 4. Felt anxious, ‘keyed up’, or ‘on edge’ | |

| Psychological | Decreased interest in usual activities (e.g., work, school, friends, hobbies) | DRSP 9. Had less interest in usual activities (e.g., work, school, friends, hobbies) |

| Subjective difficulty in concentration | DRSP 10. Had difficulty concentrating | |

| A sense of being overwhelmed or out of control | DRSP 16. Felt overwhelmed, that I couldn’t cope |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| AGE | 25.77 (4.88) | |

| RACE | ||

| White | 33.33 | |

| Black or African American | 17.78 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.00 | |

| Asian | 37.78 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.00 | |

| More than one race | 4.44 | |

| Unknown/do not want to specify | 6.67 | |

| ETHNICITY | ||

| Hispanic | 15.55 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 80.00 | |

| Do not know/Do not want to specify | 4.44 | |

| STUDENT STATUS | ||

| Yes | 42.22 | |

| No | 57.78 | |

| MARITAL STATUS | ||

| Single, never married | 91.11 | |

| Married | 8.89 | |

| INCOME | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 55.56 | |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 13.33 | |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 11.11 | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 15.56 | |

| $75,000 or more | 4.44 | |

| AGE OF MENACHE | 12.03 (1.11) | |

| BMI | 24.51 (4.45) | |

| BECKS DEPRESSION INVENTORY (BDI) | 4.27 (5.14) | |

| SOCIAL ADAPTATION SELF EVALUATION SCALE (SASS) | 46.70 (6.19) | |

| STATE TRAIT ANXIETY INVENTORY (Y-2) | 36.37 (7.85) |

| Premenstrual Symptom | Unadjusted Model | Model Adjusted for Age | Model Adjusted for Age and Age of Menarche | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edf | Deviance Explained | F | p-Adjusted * | Edf | Deviance Explained | F | p-Adjusted * | Edf | Deviance Explained | F | p-Adjusted * | |

| Affective Lability | 1 | 7.24% | 3.355 | 0.1722 | 1 | 10.7% | 3.742 | 0.1393 | 1 | 21% | 5.081 | 0.07536667 |

| Irritability/Anger | 1 | 4.64% | 2.092 | 0.217 | 1 | 7.9% | 2.352 | 0.166833 | 1 | 19.2% | 4.399 | 0.079275 |

| Depression | 1 | 3.92% | 1.754 | 0.224 | 1 | 7.65% | 2.232 | 0.166833 | 1 | 14.2% | 2.546 | 0.1708 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 0.0232% | 0.921 | 0.921 | 1 | 2.91% | 0.073 | 0.789 | 1 | 7.95% | 0.55 | 0.465 |

| Low Interest | 2.044 | 23.4% | 4.351 | 0.0392 * | 1.718 | 24.1% | 4.969 | 0.034195 * | 2.277 | 44.1% | 5.358 | 0.016275 * |

| Difficulty Concentrating | 1 | 17.9% | 9.394 | 0.0259 * | 1 | 24.4% | 12.06 | 0.00826 * | 1 | 48.9% | 22.62 | 0.0003339 * |

| Feeling Overwhelmed | 1 | 5.89% | 2.693 | 0.189 | 1 | 8.07% | 2.437 | 0.166833 | 1 | 12.9% | 2.099 | 0.1855 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamidovic, A.; Dang, N.; Khalil, D.; Sun, J. Association between Neuroticism and Premenstrual Affective/Psychological Symptomatology. Psychiatry Int. 2022, 3, 52-64. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint3010005

Hamidovic A, Dang N, Khalil D, Sun J. Association between Neuroticism and Premenstrual Affective/Psychological Symptomatology. Psychiatry International. 2022; 3(1):52-64. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint3010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamidovic, Ajna, Nhan Dang, Dina Khalil, and Jiehuan Sun. 2022. "Association between Neuroticism and Premenstrual Affective/Psychological Symptomatology" Psychiatry International 3, no. 1: 52-64. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint3010005

APA StyleHamidovic, A., Dang, N., Khalil, D., & Sun, J. (2022). Association between Neuroticism and Premenstrual Affective/Psychological Symptomatology. Psychiatry International, 3(1), 52-64. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint3010005