Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) Inhibitors: A Therapeutic Double-Edged Sword in Immunity and Inflammation

Abstract

1. Introduction

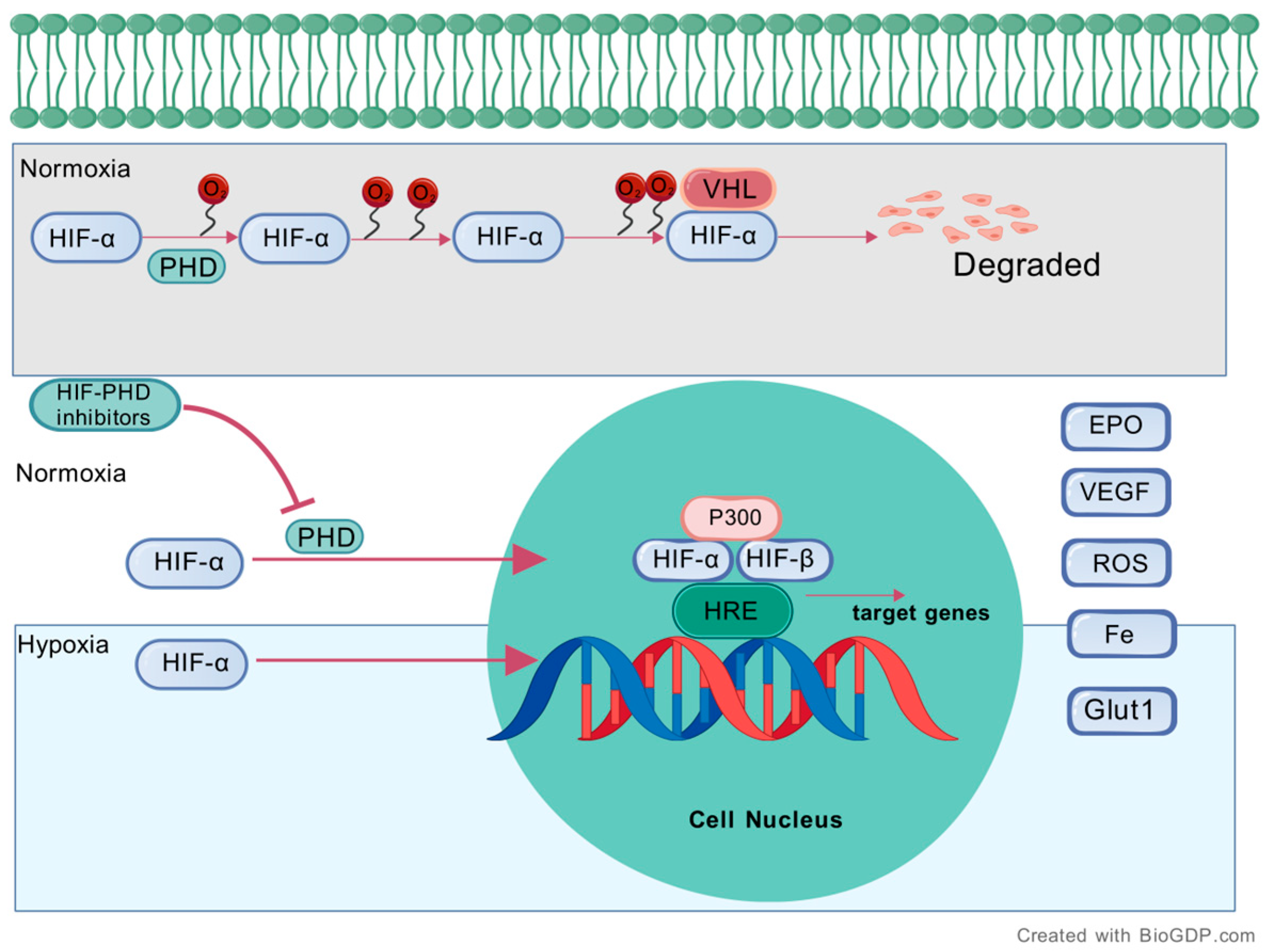

2. Mechanistic Basis of HIF-PHD Inhibitor Action

2.1. Overview of the HIF Pathway

2.2. Regulation of the HIF Pathway by HIF-PHD Inhibitors

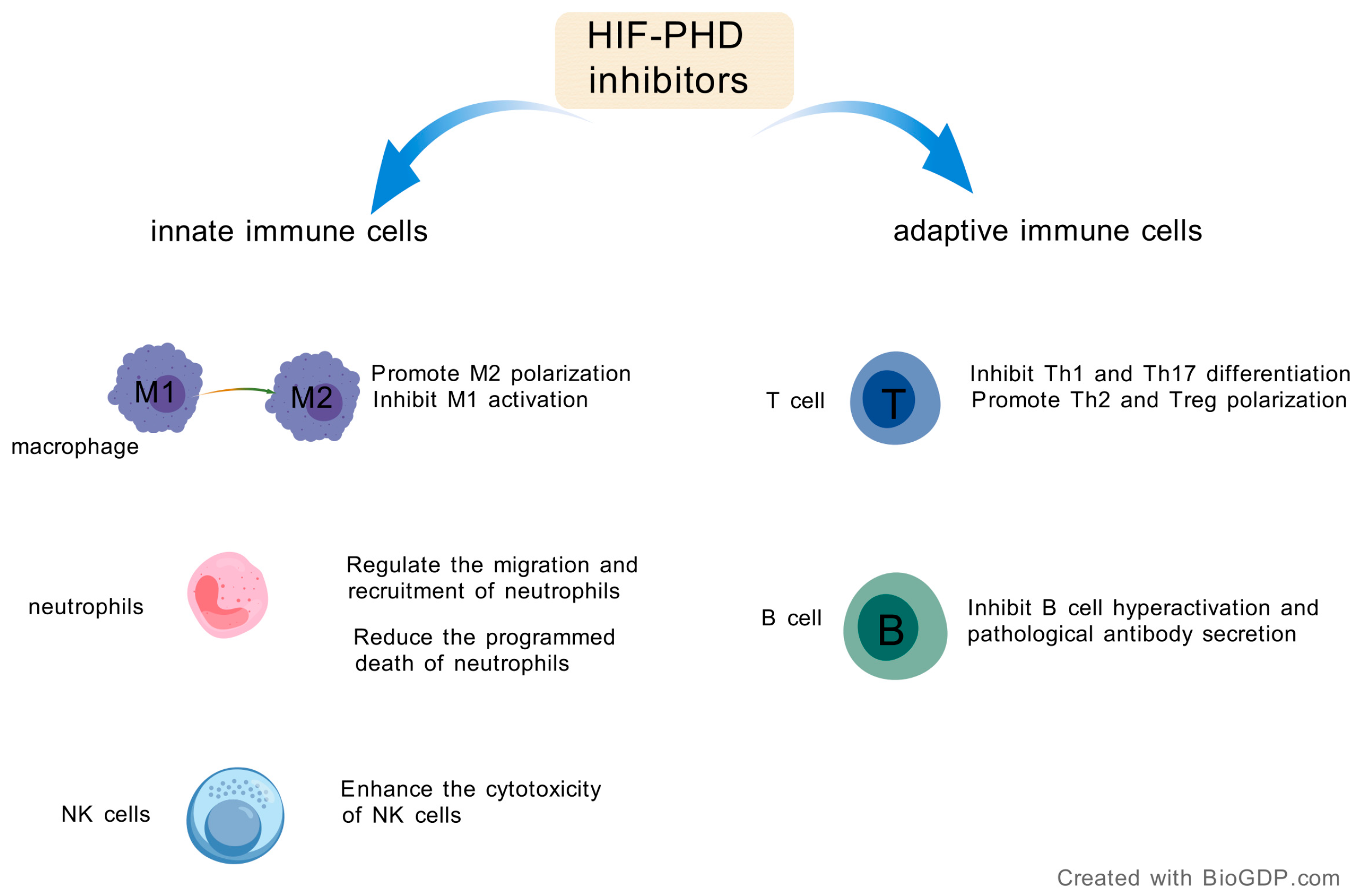

3. Modulation of Innate Immunity by HIF-PHD Inhibitors

3.1. Recalibrating Macrophage Polarization

3.2. Regulating Neutrophil Function and Trafficking

3.3. Enhancing Natural Killer (NK) Cell Cytotoxicity

4. Regulatory Effects of HIF-PHD Inhibitors on Adaptive Immune Cells

4.1. HIF-PHD Inhibition and T Cell-Mediated Immunity

4.2. HIF-PHD Inhibition and B Cell Responses

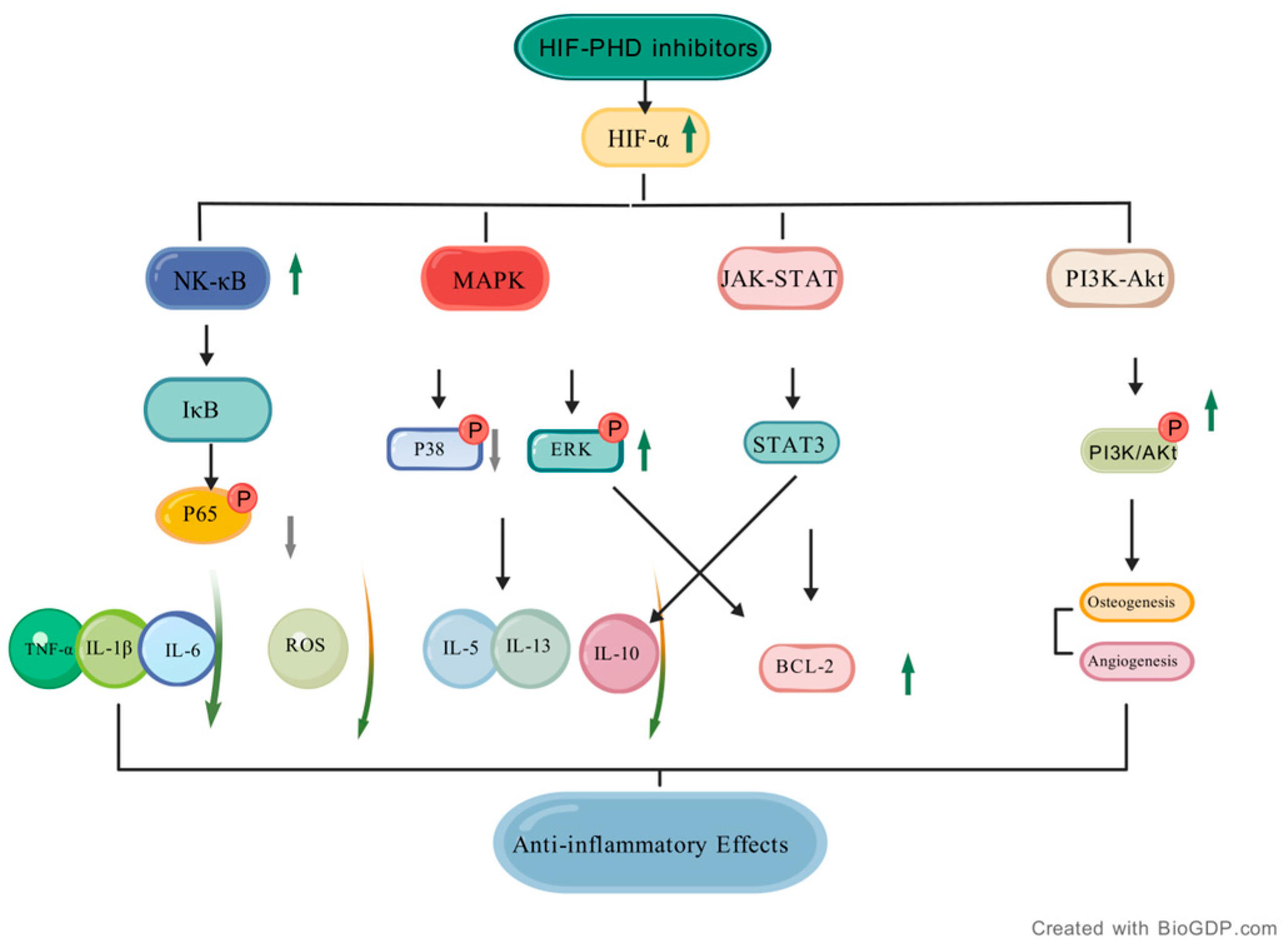

5. Regulatory Effects of HIF-PHD Inhibitors on Inflammatory Signaling Pathways

5.1. NF-κB Signaling Pathway

5.2. MAPK Signaling Pathway

5.3. JAK-STAT Pathway

5.4. PI3K-Akt Pathway

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HIF-α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-alpha |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-kappa B |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| PI3K-Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase-Protein Kinase B |

| IκB | Inhibitor of kappa B |

| P38 | P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B |

| TNF-α | umor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| IL-5 | Interleukin-5 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| BCL-2 | B-Cell Lymphoma-2 |

| P65 | Nuclear Factor-kappa B p65 |

| HIF-PHD | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase |

| IOX2 | 2-(1-benzyl-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamido) acetic acid |

| VHL | von Hippel-Lindau |

| RhoA GTPase | RhoA Guanosine Triphosphatase |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 |

| ST2L | Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2, Long isoform |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal Kinase |

| MKK3 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 3 |

| MKK6 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 6 |

| mTOR | mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| eIF4E | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| UCP2 | Uncoupling Protein 2 |

| HSP90 | Heat Shock Protein 90 |

References

- Semenza, G.L.; Wang, G.L. A Nuclear Factor Induced by Hypoxia via de Novo Protein Synthesis Binds to the Human Erythropoietin Gene Enhancer at a Site Required for Transcriptional Activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 5447–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, K. HIF-α Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors and Their Implications for Biomedicine: A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, P.; Mole, D.R.; Tian, Y.M.; Wilson, M.I.; Gielbert, J.; Gaskell, S.J.; Von Kriegsheim, A.; Hebestreit, H.F.; Mukherji, M.; Schofield, C.J.; et al. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau Ubiquitylation Complex by O2-Regulated Prolyl Hydroxylation. Science 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, J. HIFα Targeted for VHL-Mediated Destruction by Proline Hydroxylation: Implications for O2 Sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, R.W. Novel Compounds as PHD Inhibitors for Treating Heart, Lung, Liver, and Kidney Diseases. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1868–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, P.H.; Eckardt, K.U. HIF Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Renal Anaemia and Beyond. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L. HIF-1 and Mechanisms of Hypoxia Sensing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001, 13, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenk, S.F.; Hauck, S.; Mayer, D.; Grieshober, M.; Stenger, S. Stabilization of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Promotes Antimicrobial Activity of Human Macrophages Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 678354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, S. Roxadustat: First Global Approval. Drugs 2019, 79, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, I.C. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Enzyme Inhibitors: Ready for Primetime? Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2022, 31, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimaki, A.; Ohuchi, K.; Takizawa, S.; Murakami, T.; Kurita, H.; Hozumi, I.; Wen, X.; Kitamura, Y.; Wu, Z.; Maekawa, Y.; et al. The Neuroprotective Effects of FG-4592, a Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor, against Oxidative Stress Induced by Alpha-Synuclein in N2a Cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Li, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X. The Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor Roxadustat: Paradigm in Drug Discovery and Prospects for Clinical Application beyond Anemia. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, S.; Majedi, H.; Dehpour, A.R.; Dehghan, S.; Jafarian, M.; Hadjighassem, M.; Hosseindoost, S. Ferroptosis as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma: Mechanisms and emerging strategies. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Khan, H.; Kumar, A.; Grewal, A.K.; Dua, K.; Singh, T.G. Pharmacological Modulation of HIF-1 in the Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J. Neural Transm. 2023, 130, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, R.; Dong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Yin, Y.; Che, X.; Wu, G.; Guo, L.; et al. IHH–GLI-1–HIF-2α Signalling Influences Hypertrophic Chondrocytes to Exacerbate Osteoarthritis Progression. J. Orthop. Translat. 2024, 49, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, B.; Dong, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Ge, Q.; Niu, F.; Liu, B. HIF-1α Participates in Secondary Brain Injury through Regulating Neuroinflammation. Transl. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 20220272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wu, Q.Y.; Teng, X.H.; Li, Z.P.; Zhu, M.T.; Gu, C.J.; Chen, B.J.; Xie, Q.Q.; Luo, X.J. The Pathogenesis and Regulatory Role of HIF-1 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2023, 48, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchowicz, M.A.; Parveen, K.; Sethuraman, A.; Ishrat, T.; Xu, K.; LaManna, J. Pro-Survival Phenotype of HIF-1α: Neuroprotection Through Inflammatory Mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1438, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.T.; Scholz, C.C. The Effect of HIF on Metabolism and Immunity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarmizi, A.A.; Adam, S.H.; Nik Ramli, N.N.; Hadi, N.A.; Abdul Mutalib, M.; Tang, S.G.H.; Mokhtar, M.H. The ameliorative Effects of selenium nanoparticles (SENPs) on Diabetic rat model: A Narrative review. Sains Malays. 2023, 52, 2037–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik Ramli, N.N.; Omar, N.; Husin, A.; Ismail, Z.; Siran, R. Preconditioning effect of (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine on ischemic injury in middle cerebral artery occluded Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 588, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik Ramli, N.N.; Siran, R. The neuroprotective effects of (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine preconditioning in middle cerebral artery occluded rats: A perspective as a contrivance for stroke. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 1221–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pewklang, T.; Chansaenpak, K.; Bakar, S.N.; Lai, R.; Kue, C.S.; Kamkaew, A. Aza-BODIPY based carbonic anhydrase IX: Strategy to overcome hypoxia limitation in photodynamic therapy. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1015883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzeszczak, W.; Szczyra, D.; Śnit, M. Whether Prolyl Hydroxylase Blocker—Roxadustat—In the Treatment of Anemia in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Is the Future? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Zheng, N. Roxadustat, a HIF-PHD Inhibitor with Exploitable Potential on Diabetes-Related Complications. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1088288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Bae, S.H.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, K.W. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF-1) α: Its Protein Stability and Biological Functions. Exp. Mol. Med. 2004, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Costa, M. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marxsen, J.H.; Stengel, P.; Doege, K.; Heikkinen, P.; Jokilehto, T.; Wagner, T.; Jelkmann, W.; Jaakkola, P.; Metzen, E. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) Promotes Its Degradation by Induction of HIF-α-Prolyl-4-Hydroxylases. Biochem. J. 2004, 381, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voit, R.A.; Sankaran, V.G. Stabilizing HIF to Ameliorate Anemia. Cell 2020, 180, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakleh, M.Z.; Al Haj Zen, A. The Distinct Role of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in Hypoxia and Angiogenesis. Cells 2025, 14, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracken, C.P.; Fedele, A.O.; Linke, S.; Balrak, W.; Lisy, K.; Whitelaw, M.L.; Peet, D.J. Cell-Specific Regulation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)-1α and HIF-2α Stabilization and Transactivation in a Graded Oxygen Environment. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 22575–22585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennel, K.B.; Burmeister, J.; Schneider, M.; Taylor, C.T. The PHD1 Oxygen Sensor in Health and Disease. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 3899–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wu, J.; Tang, H.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Generic Diagramming Platform (GDP): A Comprehensive Database of High-Quality Biomedical Graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1670–D1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso, T.; Matsue, Y.; Mizukami, A.; Tokano, T.; Isoda, K.; Suwa, S.; Miyauchi, K.; Yanagisawa, N.; Okumura, Y.; Minamino, T. Daprodustat for Anaemia in Patients with Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Randomized Controlled Study. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 4291–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, I.; Tanaka, T.; Nangaku, M. Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of Vadadustat for the Treatment of Anemia Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, A. Enarodustat: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Hao, C.; Liu, B.-C.; Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Xing, C.; Liang, X.; Jiang, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Roxadustat Treatment for Anemia in Patients Undergoing Long-Term Dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.L.; Tu, Y.; Liu, B.C. Treatment of Renal Anemia with Roxadustat: Advantages and Achievement. Kidney Dis. 2020, 6, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, N.R. The Safety of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents for the Treatment of Anemia Resulting from Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Drug Investig. 2016, 36, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, E.; Imai, A. The Comparison of Four Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors on Drug Potency and Cost for Treatment in Patients with Renal Anemia. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2024, 28, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Desidustat: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joharapurkar, A.; Pandya, V.; Patel, H.; Jain, M.; Desai, R. Desidustat: A Novel PHD Inhibitor for the Treatment of CKD-Induced Anemia. Front. Nephrol. 2024, 4, 1459425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jin, Q.; Fan, J.; Xu, X.; Gu, R.; Hao, H.; Zhang, A.; et al. Clinical Potential of Hypoxia Inducible Factors Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors in Treating Nonanemic Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 837249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Xun, J.; Li, T.; Jiang, X.; Liu, B.; Hu, Z.; Yang, H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Z.; Wu, X.; et al. FATS alleviates ulcerative colitis by inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization and aerobic glycolysis through promoting the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of HIF-1α. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 240, 117053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaruba, M.M.; Staggl, S.; Ghadge, S.K.; Maurer, T.; Gavranovic-Novakovic, J.; Jeyakumar, V.; Schönherr, P.; Wimmer, A.; Pölzl, G.; Bauer, A.; et al. Roxadustat Attenuates Adverse Remodeling Following Myocardial Infarction in Mice. Cells 2024, 13, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Hua, H.; Lu, Y.; Yan, K.; Zheng, Y.; Jia, Z.; Guo, H.; Li, M.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Z. Roxadustat Ameliorates Experimental Colitis in Mice by Regulating Macrophage Polarization through Increasing HIF Level. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2024, 1868, 130548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBerge, M.; Schroth, S.; Du, F.; Yeap, X.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Ansari, M.J.; Scott, E.A.; Thorp, E.B. Hypoxia Inducible Factor 2α Promotes Tolerogenic Macrophage Development during Cardiac Transplantation through Transcriptional Regulation of Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319623121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Cao, Y.; Feng, L. Roles of Hypoxic Environment and M2 Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles on the Progression of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Takeda, N. The Roles of HIF-1α Signaling in Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sormendi, S.; Deygas, M.; Sinha, A.; Bernard, M.; Krüger, A.; Kourtzelis, I.; Le Lay, G.; Sáez, P.J.; Gerlach, M.; Franke, K.; et al. HIF2α Is a Direct Regulator of Neutrophil Motility. Blood 2021, 137, 3416–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dölling, M.; Eckstein, M.; Singh, J.; Schauer, C.; Schoen, J.; Shan, X.; Bozec, A.; Knopf, J.; Schett, G.; Muñoz, L.E.; et al. Hypoxia Promotes Neutrophil Survival After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 726153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, L.; Eulenberg-Gustavus, C.; Jerke, U.; Rousselle, A.; Eckardt, K.; Schreiber, A.; Kettritz, R. B2-Integrins Control HIF1α Activation in Human Neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1406967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.G.; Gao, Y.Y.; Yin, Z.Q.; Wang, X.R.; Meng, X.S.; Zou, T.F.; Duan, Y.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Liao, C.Z.; Xie, Z.L.; et al. Roxadustat Alleviates Nitroglycerin-Induced Migraine in Mice by Regulating HIF-1α/NF-ΚB/Inflammation Pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Waheed, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, K.; Zhou, X. The Role of Roxadustat in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Complicated with Anemia. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, N.A.; Pereverzeva, L.; Leopold, V.; Ramirez-Moral, I.; Roelofs, J.J.T.H.; Van Heijst, J.W.J.; De Vos, A.F.; Van Der Poll, T. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 α in Macrophages, but Not in Neutrophils, Is Important for Host Defense during Klebsiella pneumoniae—Induced Pneumosepsis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 9958281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.A.; Moon, Y.; Shin, M.H.; Kim, T.J.; Chae, S.; Yee, C.; Hwang, D.; Park, H.; Lee, K.M. Hypoxia-Driven Hif-1α Activation Reprograms Pre-Activated Nk Cells towards Highly Potent Effector Phenotypes via Erk/Stat3 Pathways. Cancers 2021, 13, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Río, A.G.D.; Prieto-Fernández, E.; Egia-Mendikute, L.; Antoñana-Vildosola, A.; Jimenez-Lasheras, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Barreira-Manrique, A.; Zanetti, S.R.; De Blas, A.; Velasco-Beltrán, P.; et al. Factor-Inhibiting HIF (FIH) Promotes Lung Cancer Progression. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e167394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wu, A.; Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Wen, Y.; Wu, H.; Yan, N.; Yang, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, P. Eleutheroside A Inhibits PI3K/AKT1/MTOR-Mediated Glycolysis in MDSCs to Alleviate Their Immunosuppressive Function in Gastric Cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 159, 114907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluff, E.; Magdaleno, C.C.; Fernandez, E.; House, T.; Swaminathan, S.; Varadaraj, A.; Rajasekaran, N. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Alpha Expression Is Induced by IL-2 via the PI3K/MTOR Pathway in Hypoxic NK Cells and Supports Effector Functions in NKL Cells and Ex Vivo Expanded NK Cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 1989–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, A.; Nelius, E.; Fan, Z.; Khatchatourova, E.; Alvarado-Diaz, A.; He, J.; Krzywinska, E.; Sobecki, M.; Nagarajan, S.; Kerdiles, Y.; et al. Resting Natural Killer Cell Homeostasis Relies on Tryptophan/ NAD+ Metabolism and HIF-1α. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e56156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojkovic, M.; Cunha, P.P.; Darmasaputra, G.S.; Barbieri, L.; Rundqvist, H.; Veliça, P.; Johnson, R.S. Oxy gen-Mediated Suppression of CD8+ T Cell Proliferation by Macrophages: Role of Pharmacological Inhibitors of HIF Degradation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 633586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ohara, T.; Hamada, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, M.; Noma, K.; Tazawa, H.; Fujisawa, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Matsukawa, A. HIF-PH Inhibitors Induce Pseudohypoxia in T Cells and Suppress the Growth of Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer by Enhancing Antitumor Immune Responses. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Pissas, G.; Mavropoulos, A.; Nikolaou, E.; Filippidis, G.; Liakopoulos, V.; Stefanidis, I. In Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction, the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl-Hydroxylase Inhibitor Roxadustat Suppresses Cellular and Humoral Alloimmunity. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2020, 68, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Pissas, G.; Liakopoulos, V.; Stefanidis, I. On the Increased Event Rate of Urinary Tract Infection and Pneumonia in CKD Patients Treated with Roxadustat for Anemia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strowitzki, M.J.; Kimmer, G.; Wehrmann, J.; Ritter, A.S.; Radhakrishnan, P.; Opitz, V.M.; Tuffs, C.; Biller, M.; Kugler, J.; Keppler, U.; et al. Inhibition of HIF-Prolyl Hydroxylases Improves Healing of Intestinal Anastomoses. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e139191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, A.F.; Liang, J.X.; Yao, L.; Han, J.L.; Zhou, L.J. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor Roxadustat (FG-4592) Protects against Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Inflammation. Ren. Fail. 2021, 43, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. Targeting NF-ΚB Pathway for the Therapy of Diseases: Mechanism and Clinical Study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-ΚB in Biology and Targeted Therapy: New Insights and Translational Implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.; Geng, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, T.; Yue, X.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, X.; Hou, X.Y.; et al. Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor FG-4592 Alleviates Neuroin-flammation via HIF-1/BNIP3 Signaling in Microglia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Lun, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J. PHD3 Inhibits Colon Cancer Cell Metastasis through the Occludin-P38 Pathway. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2023, 55, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, R.; Ishikawa, H.; Kuno, Y.; Kohda, C.; Iyoda, M. HIF-PHD Inhibitor Regulates the Function of Group2 Innate Lymphoid Cells and Polarization of M2 Macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Bai, L.; Tong, Y.; Guo, S.; Lu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, W.; Jin, Y.; Gao, P.; Liu, J. CIRP Attenuates Acute Kidney Injury after Hypothermic Cardiovascular Surgery by Inhibiting PHD3/HIF-1α-Mediated ROS-TGF-Β1/P38 MAPK Activation and Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.F.; Shen, G.Z.; Gong, P.F.; Yang, Y.; Tuerxun, P. Mechanisms of Action of the Proline Hydroxylase-Adenosine Pathway in Regulating Apoptosis and Reducing Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2025, 89, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, J.; Ortega, Á.L.; Guryanova, S.V.; Maksimova, T.V.; Azova, M.M.; Shemyakin, M.M.; Ovchinnikov, Y.A. Transcription Factors and Methods for the Pharmacological Correction of Their Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, A.; Rao, P.; Pranay, A.; Xu, K.; LaManna, J.C.; Puchowicz, M.A. Chronic Ketosis Modulates HIF1α-Mediated Inflammatory Response in Rat Brain. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1269, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Byrne, N.M.; Al Jamal, W.; Coulter, J.A. Exploiting Current Understanding of Hypoxia Mediated Tumour Progression for Nanotherapeutic Development. Cancers 2019, 11, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, R.; Yao, S.; Meng, F.; Kong, L. HIF-1A as a Prognostic Biomarker Related to Invasion, Migration and Immunosuppression of Cervical Cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Ma, C.; Yang, B.; Zhao, M.; Sun, L.; Zheng, N. Roxadustat Improves Diabetic Myocardial Injury by Upregulating HIF-1α/UCP2 against Oxidative Stress. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Lv, H.; Zhai, S.; Liu, M.; Liu, X.; Sezhen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Mild Ther motherapy-Assisted GelMA/HA/MPDA@Roxadustat 3D-Printed Scaffolds with Combined Angiogenesis-Osteogenesis Functions for Bone Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2400545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.H.; Yue, Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Chiang, J.Y.; Cheng, B.C.; Yang, C.C.; Chai, H.T.; Yip, H.K. Combined Dapagliflozin and Roxadustat Effectively Protected Heart and Kidney against Cardiorenal Syndrome-Induced Damage in Rodent through Activation of Cell Stress-Nfr2/ARE Signalings and Stabilizing HIF-1α. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, A.; Gan, L.; Zuo, L. Roxadustat Improves Renal Osteodystrophy by Dual Regulation of Bone Re modeling. Endocrine 2023, 79, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.; Chen, H.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, L.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Xia, W. Antianemia Drug Roxadustat (FG-4592) Protects Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardio-toxicity by Targeting Antiapoptotic and Antioxidative Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 556041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, S.; Meyers, D.J.; Wicks, E.E.; Lee, S.N.; Datan, E.; Thomas, A.M.; Anders, N.M.; Hwang, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. HIF Inhibitor 32-134D Eradicates Murine Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Combination with Anti-PD1 Therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e156774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, S.J.; Koh, M.Y. Revisiting the HIF Switch in the Tumor and Its Immune Microenvironment. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolahi, F.; Shahraki, A.; Sheervalilou, R.; Mortazavi, S.S. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes Associated with the Pathogenesis of Gastric Cancer by Bioinformatics Analysis. BMC Med. Genom. 2023, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.C.; Taylor, C.T. Targeting the HIF Pathway in Inflammation and Immunity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013, 13, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerdes, I.; Matikas, A.; Foukakis, T. The Interplay between Eosinophils and T Cells in Breast Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article | Disease or Disease Model | HIF-PHD Inhibitors Name | Immune or Inflammatory Pathways Validated in the Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sung et al. [80] | Rat cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) | Roxadustat | Nrf2/ARE;PI3K/Akt/mTOR |

| Fang et al. [25] | Diabetic myocardial injury (mouse model/high glucose-induced rat cardiomyocyte model) | Roxadustat (FG-4592) | PI3K/AKT/Nrf2;Nrf2,HO-1,SOD2;alleviates oxidative stress |

| Li et al. [81] | Osteoporosis (ovariectomized rat model) | Roxadustat | Wnt/β-catenin;differentiation-related factors (Runx2, OCN) |

| Nagashima et al. [71] | Renal fibrosis | GSK360A, FG-4592 | IL-33/ST2L/p38 MAPK;IL-5/IL-13 by ILC2 cells |

| Li et al. [23] | Cisplatin chemotherapy-induced nephrotoxicity(acute kidney injury) | Roxadustat (FG-4592) | HIF-related antioxidant and anti-apoptotic pathways |

| Sharma et al. [14] | Acute kidney injury (rat ischemia–reperfusion model), chronic kidney disease (mouse adenine-induced model) | Desidustat | IL-1β,IL-6,myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, MDA levels |

| Zenk et al. [8] | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection (human macrophage model) | Molidustat | TNFα,IL-10,p38,MAP kinase pathway |

| Long et al. [82] | Doxorubicin (DOX)-induced cardiotoxicity (mouse model and H9c2, HL-1, NRVM cell models) | Roxadustat (FG-4592) | TNF-α/IL-6 |

| Salman et al. [83] | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (mouse Hepa1-6 model, human Hep3B cell model) | 32-134D | CD8+ T cells/NK cells, VEGFA,IL-6/IL-10, CXCL9/CXCL10 |

| Cowman et al. [84] | Various solid tumors (clear cell renal cell carcinoma, neuroblastoma, glioblastoma, etc.) | Belzutifan(PT2977), PT2385, PT2399, etc. | TAM polarization, T cell activity, and PD-L1 expression |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Ramli, N.N.N. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) Inhibitors: A Therapeutic Double-Edged Sword in Immunity and Inflammation. J. Mol. Pathol. 2025, 6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040025

Li Q, Ramli NNN. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) Inhibitors: A Therapeutic Double-Edged Sword in Immunity and Inflammation. Journal of Molecular Pathology. 2025; 6(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qinyun, and Nik Nasihah Nik Ramli. 2025. "Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) Inhibitors: A Therapeutic Double-Edged Sword in Immunity and Inflammation" Journal of Molecular Pathology 6, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040025

APA StyleLi, Q., & Ramli, N. N. N. (2025). Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) Inhibitors: A Therapeutic Double-Edged Sword in Immunity and Inflammation. Journal of Molecular Pathology, 6(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp6040025